Abstract

The authors compared trends in and levels of coronary heart disease (CHD) risk factors between the Minneapolis-St. Paul, Minnesota, metropolitan area (Twin Cities) and the entire US population to help explain the ongoing decline in US CHD mortality rates. The study populations for risk factors were adults aged 25–74 years enrolled in 2 population-based surveillance studies: the Minnesota Heart Survey (MHS) in 1980–1982, 1985–1987, 1990–1992, 1995–1997, and 2000–2002 and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) in 1976–1980, 1988–1994, 1999–2000, and 2001–2002. The authors found a continuous decline in CHD mortality rates in the Twin Cities and nationally between 1980 and 2000. Similar decreasing rates of change in risk factors across survey years, parallel to the CHD mortality rate decline, were observed in MHS and in NHANES. Adults in MHS had generally lower levels of CHD risk factors than NHANES adults, consistent with the CHD mortality rate difference. Approximately 47% of women and 44% of men in MHS had no elevated CHD risk factors, including smoking, hypertension, high cholesterol, and obesity, versus 36% of women and 34% of men in NHANES. The better CHD risk factor profile in the Twin Cities may partly explain the lower CHD death rate there.

Keywords: cardiovascular diseases, coronary disease, Minnesota, population surveillance, risk factors

The national rate of death due to cardiovascular disease (CVD) in 2005 was 277 per 100,000 population, representing a 46% decline from 1981 (1, 2). In contrast, Minnesota had one of the lowest age-adjusted CVD death rates nationally (208/100,000 population) and the greatest percent change (−35%) among states between 1995 and 2005, raising the question of whether Minnesota may have better CVD risk factor levels from preventive management and/or cardiovascular care than other states (2, 3).

Monitoring the trends in CVD risk factors in populations enhances our understanding of mortality trends, since these trends are dynamic and are influenced by the health environment, personal health behaviors, and medical care. According to a previous report, 44% of the decline in CVD mortality among US adults between 1980 and 2000 was due to changes in CVD risk factors (4). Specifically, reductions in total cholesterol, blood pressure, smoking, and physical inactivity contributed 24%, 20%, 12%, and 5%, respectively, to the decreased CVD mortality rate (4). However, the national obesity epidemic has been associated with increased prevalence of diabetes and elevations in blood pressure and lipid levels (5, 6). Changes in eating patterns have also been demonstrated (7). There is already evidence that the prevalence of hypertension is increasing in adults and children (8, 9). Such empirical data on population risk factor levels and trends are required for appropriate public health and medical policy.

Surveillance provides an integrated assessment of health and risk trends in populations. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), for example, provides a picture of the nation's health and has been actively conducted since the 1960s (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm). Although NHANES assesses many diseases and health characteristics, the sampling frame and sample size do not allow detailed analysis of specific geographic areas, even those with large populations. The Minnesota Heart Survey (MHS), which has been ongoing since 1980, provides a more detailed and specific look at CVD risk in a large population (2.6 million in the 2000 US Census) involving consistent measurement methods over a 20-year period (10, 11).

In this study, we compared the trends in CVD risk factors in the Minneapolis-St. Paul metropolitan area with those in the United States as a whole using data from the MHS (1980–1982 through 2000–2002) and NHANES (NHANES II (1976–1980) through NHANES 2001–2002). Through this comparison, we aimed to better understand why Minnesotans have a lower CVD mortality rate than the US general population. We hypothesized that both coronary heart disease (CHD) mortality and risk status are generally more favorable in Minnesota than in the United States as a whole and that Minnesotans have had a somewhat greater rate of decline in both risk factors and CHD mortality.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

The MHS, approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board, has been described previously (10, 11). Briefly, MHS is a population-based surveillance study of trends in CVD risk factors. The study population includes independent probability samples of noninstitutionalized adults in a defined geographic area: the 7-county metropolitan area of Minneapolis/St. Paul. Surveys were conducted in 1980–1982, 1985–1987, 1990–1992, 1995–1997, and 2000–2002. In each survey, 40 (1980–1992) or 44 (1995–2002) clusters were randomly selected from 704 clusters, and from each cluster, households were randomly selected to generate a sample size of approximately 5,000 adults. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Participants were asked to complete a home interview and to undertake a clinic visit. Home interviews comprised questions about demographic characteristics and health behaviors. In the clinic, more detailed information about medical history, diet, and physical activity was obtained. Anthropometric and blood pressure measurements were taken, and a nonfasting blood specimen was drawn.

NHANES is a population-based survey of the health and nutritional status of the noninstitutionalized US population aged 2 months or older. Information is obtained through a home interview and clinical examination. Surveys were originally conducted in 1971–1975, 1976–1980, and 1988–1994, named NHANES I, II, and III, respectively. Since 1999, the surveys have been conducted on a continuous basis (1999–2000, 2001–2002, 2003–2004, etc.). In each census cycle, a multistage, stratified sampling design is used to select a nationally representative sample of civilian, noninstitutionalized residents of the United States. Details about the NHANES sampling strategies are available online (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm).

Study population

Eligibility criteria for participation in MHS risk factor surveys included being aged 25–74 years for surveys conducted in 1980–1982 and 1985–1987 and being aged 25–84 years thereafter (10, 11). In 2000–2002, youth aged 8–17 years were included in order to determine the CVD risk factor distribution among children and adolescents. Response rates for participants examined in surveys conducted in 1980–1982 through 2000–2002 were 69.1% (n = 4,083), 68.1% (n = 5,734), 68.4% (n = 6,304), 64.8% (n = 6,284), and 64.0% (n = 4,159), respectively (10, 11).

NHANES II (1976–1980) comprised 27,801 persons aged 6 months to 74 years, and NHANES III (1988–1994) comprised 39,695 persons aged 2 months or older (12). The continuous surveys conducted from 1999 onward included fewer persons. For 1999–2000, a total of 6,401 people aged 20 years or older were interviewed and examined, while for 2001–2002, there were 6,911 participants (12). The surveys oversampled racial/ethnic minorities to increase the reliability and precision of estimates of health status indicators for these subgroups. Overall response rates for adults aged 20–79 years examined in NHANES II (1976–1980), NHANES III (1988–1994), NHANES 1999–2000, and NHANES 2001–2002 were 68%, 71%, 71%, and 74%, respectively (12).

For this study, MHS and NHANES data were restricted to adults aged 25–74 years.

Ascertainment of CHD mortality

Mortality due to CHD (underlying cause of death) was defined as International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (13), codes 410–414 (ischemic heart disease). Mortality data for the residents of the Minneapolis-St. Paul metropolitan area were obtained through linkage with the Minnesota Death Index, a system that has 98% agreement with the National Death Index (14). US mortality data were obtained from the National Death Index. These data were age-standardized to the 2000 US population.

Measurements

Demographic characteristics, health habits, and medical history were assessed by means of interviewer-administered questionnaires in MHS and NHANES. Health insurance information was also obtained.

In MHS, height was measured with a rigid ruler attached to a wall and a wooden triangle while the participant stood in stocking feet on a firm floor. In NHANES, height was measured using a fixed stadiometer while the participant stood with his or her heels, buttocks, shoulder blades, and back of the head against the wall.

In MHS, weight was measured on a balance-beam scale with participants wearing lightweight clothing and no shoes. In NHANES II, body weight was measured using a self-balancing scale, while in later NHANES examinations, participants were measured on a Toledo digital scale while wearing only underwear.

Waist circumference was not measured in MHS in 1980–1982 or 1985–1987 or in NHANES II. In MHS, from 1990–1992 through the 2000–2002 survey, with the participant standing in lightweight clothing, waist circumference was measured at the narrowest part of the torso using an anthropometric tape aligned horizontally with the floor. In NHANES III, waist circumference was measured at the junction of the iliac crest and the midaxillary line, whereas from 1999 onward, it was measured at the natural waist midpoint between the lowest aspect of the rib cage and the highest point of the iliac crest.

In MHS, from 1980–1982 through 1995–1997, blood pressure was measured with a Hawksley random-zero sphygmomanometer (Hawksley, West Sussex, United Kingdom); during 1995–1997, the Dinamap device (GE Medical Systems Information Technologies, Inc., Milwaukee, Wisconsin) was also used in addition to the random-zero device; and during 2000–2002, only the Dinamap device was used. The average of 2 measurements taken at rest was calculated and was calibrated to the mercury sphygmomanometer. In NHANES, measurements were performed using a mercury sphygmomanometer according to a standardized procedure. The result was generated from the average of 3 measurements for each subject (15).

In MHS, nonfasting serum cholesterol level was measured. From 1980–1982 through 1990–1992, an AutoAnalyzer II (TechniCon Corporation, Emeryville, California) with a nonenzymatic method was used and calibrated against the reference Abell-Kendall method. An enzymatic method was used in 1995–1997 and 2000–2002. For NHANES II, the Liebermann-Burchard reaction method was used to analyze serum samples, and equivalent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reference values were adjusted. In NHANES III, serum cholesterol was measured on a Hitachi 717 Analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, Indiana) using commercial reagents (Roche/Boehringer Mannheim Diagnostics, Indianapolis, Indiana) on the basis of an enzymatic method developed by Allain et al. (16). Both studies used laboratories that participated in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Lipid Standardization Program.

Levels of glucose, triglycerides, and low density lipoprotein cholesterol were not assessed in MHS, because blood was drawn under a nonfasting status.

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed with SAS, version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina) and SUDAAN, version 10.0 (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina). The multistage sampling strategies were taken into account for both MHS and NHANES. To account for the oversampling in NHANES, unequal probabilities of selection, and nonresponse, we used appropriate sample weights to estimate mean values and standard errors (17). To combine data from 2 or more 2-year cycles of the continuous NHANES, we calculated new sample weights.

We created variables representing abdominal obesity (waist circumference >102 cm for men and >88 cm for women), hypercholesterolemia (serum cholesterol level ≥6.2 mmol/L or ≥240 mg/dL or current use of cholesterol-lowering medication), and hypertension (defined as ≥140 mm Hg and ≥90 mm Hg for systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure, respectively, or current use of antihypertensive medication) according to the definitions of the American Heart Association and the National Cholesterol Education Program (18, 19).

The means and frequencies of study variables were calculated for each survey. Since men and women have clinically relevant differences in CVD risk factors and CVD-related chronic disease, all analyses were stratified by gender (20). A single generalized linear mixed model for each risk factor was used to estimate level and linear trend across survey years for MHS with neighborhood cluster as a random effect, and to estimate level and linear trend for NHANES with strata and primary sampling unit pairings as random effects and appropriate sample weights. Survey year was represented as time since 1990 (e.g., 1980 was coded −10). The intercept and slope of the generalized linear mixed model represent the estimated level in 1990 and the average annual change in each CVD risk factor, respectively. The MHS and NHANES intercepts and slopes for each of the risk factors were compared, resulting in a difference in level (MHS intercept − NHANES intercept = leveldiff) and a difference in slope (MHS slope − NHANES slope = slopediff). We estimated the P value for the difference in level in 1990 (Plevel, diff) and the P value for the difference between slopes (Pslope, diff). In subgroup analyses, we restricted the MHS and NHANES samples to Caucasian participants to control for racial/ethnic differences between samples.

RESULTS

Declining trends in CHD mortality

CHD mortality rates have declined over time in both the United States generally and the Minneapolis-St. Paul metropolitan area (the MHS area), with a lower rate being seen in Minnesota. In 1980, 1990, 2000, and 2005, CHD mortality rates (per 100,000 population), age-standardized to the 2000 US Census for men aged 30–74 years in the Minneapolis-St. Paul area and nationally, were 322 vs. 346, 203 vs. 219, 114 vs. 161, and 89 vs. 135, respectively. For women in Minnesota and nationally, these rates (per 100,000 population) for the same years were 102 vs. 120, 69 vs. 82, 37 vs. 63, and 29 vs. 53, respectively. Between 1980 and 2005, the CHD mortality rates in MHS and NHANES for women fell 71% and 56%, respectively; and for men, the rates fell 72% and 61%, respectively.

Demographic characteristics of survey participants

The mean age of MHS subjects increased across survey years, while the ages of NHANES participants were similar across surveys (Table 1). Fewer racial/ethnic minorities participated in MHS than in NHANES; however, participation of minorities across survey years doubled in MHS and increased 2.5-fold in NHANES. Overall education levels among both MHS and NHANES participants consistently increased over time. Although the proportions of men and women graduating from college significantly increased across all survey years, more Minnesotans were college graduates in each survey year than were members of the general population.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Adults Enrolled in the Minnesota Heart Survey (1980–2002) and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1976–2002), by Gender

| Characteristic | Survey and Range of Survey Years |

||||||||

| Minnesota Heart Survey |

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey |

||||||||

| 1980–1982 | 1985–1987 | 1990–1992 | 1995–1997 | 2000–2002 | 1976–1980 | 1988–1994 | 1999–2000 | 2001–2002 | |

| Women | |||||||||

| Calendar yeara | 1981 | 1986 | 1991 | 1996 | 2001 | 1978 | 1991 | 2000 | 2002 |

| No. of subjects | 1,748 | 2,344 | 2,326 | 2,651 | 1,338 | 4,166 | 6,379 | 1,637 | 1,736 |

| Mean age, years | 43.9 | 44.3 | 44.6 | 45.8 | 46.1 | 46 | 45.4 | 45.2 | 45.2 |

| Race/ethnicity, % | |||||||||

| White | 96.3 | 95.9 | 95.9 | 95.3 | 90.6 | 87.5 | 84.5 | 70.5 | 72.3 |

| Black | 2.6 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 3 | 10.5 | 11.5 | 11.7 | 11 |

| Other | 1 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 2.9 | 6.4 | 2 | 4 | 17.9 | 16.7 |

| Education, % | |||||||||

| Less than high school | 11.4 | 7.3 | 5.4 | 3.6 | 3.2 | 34.9 | 22.3 | 21.5 | 17.2 |

| High school | 37.9 | 33.3 | 29.4 | 25.7 | 22.4 | 41.6 | 37.3 | 26.4 | 24.1 |

| Some college | 28.9 | 32.1 | 34.4 | 33 | 32.5 | 18.2 | 32 | 28.2 | 30.2 |

| College graduate | 21.9 | 27.3 | 30.9 | 37.8 | 41.9 | 5.2 | 8.4 | 23.9 | 28.4 |

| Men | |||||||||

| Calendar year | 1981 | 1986 | 1991 | 1996 | 2001 | 1978 | 1991 | 2000 | 2002 |

| No. of subjects | 1,560 | 2,186 | 2,160 | 2,359 | 1,193 | 3,551 | 5,698 | 1,494 | 1,649 |

| Mean age, years | 43.4 | 43.6 | 43.9 | 46.6 | 46.5 | 45.7 | 44.5 | 44.6 | 45.3 |

| Race/ethnicity, % | |||||||||

| White | 97.2 | 96.6 | 95.4 | 95.2 | 89.8 | 89.2 | 86.2 | 72.4 | 75.2 |

| Black | 1.8 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 4.7 | 8.8 | 9.8 | 9.9 | 9.1 |

| Other | 1.1 | 1.6 | 2.2 | 2.8 | 5.5 | 2 | 4.1 | 17.8 | 15.8 |

| Education, % | |||||||||

| Less than high school | 12.6 | 7.7 | 5.7 | 3.8 | 3.5 | 35.4 | 24.3 | 24.1 | 16.4 |

| High school | 24.2 | 23.6 | 23 | 20.9 | 20.2 | 33.3 | 30.6 | 24.5 | 25.9 |

| Some college | 29.8 | 32.3 | 31.9 | 29.7 | 29.5 | 19.6 | 32.7 | 24.8 | 27.4 |

| College graduate | 33.4 | 36.5 | 39.4 | 45.7 | 46.8 | 11.7 | 12.5 | 26.6 | 30.3 |

Calendar year was the time variable used for a given survey in the regression model for each variable.

Declining trends in CHD risk factors

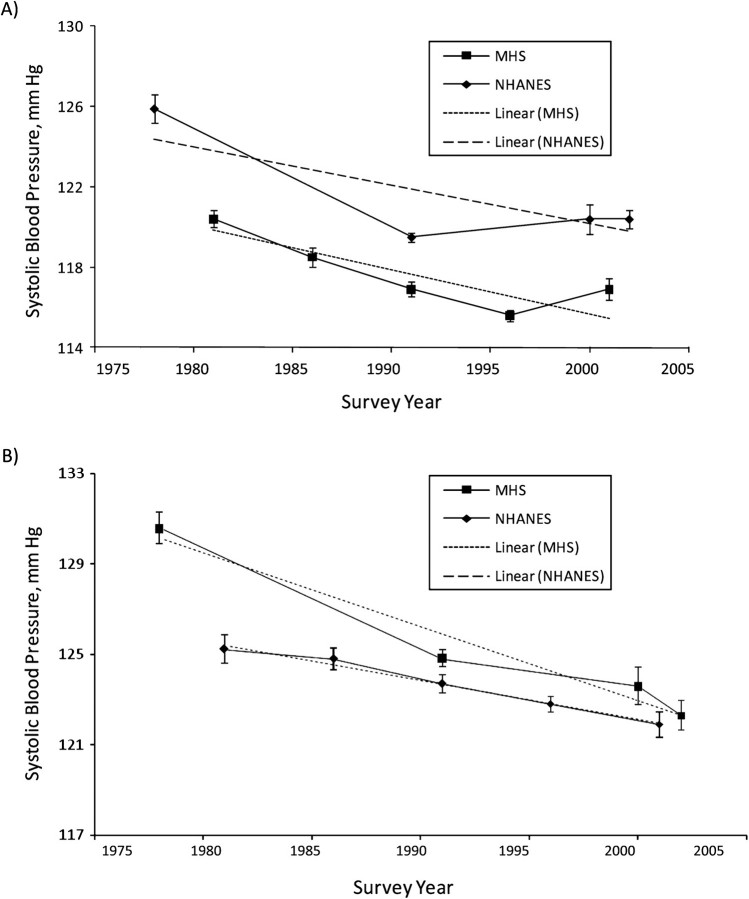

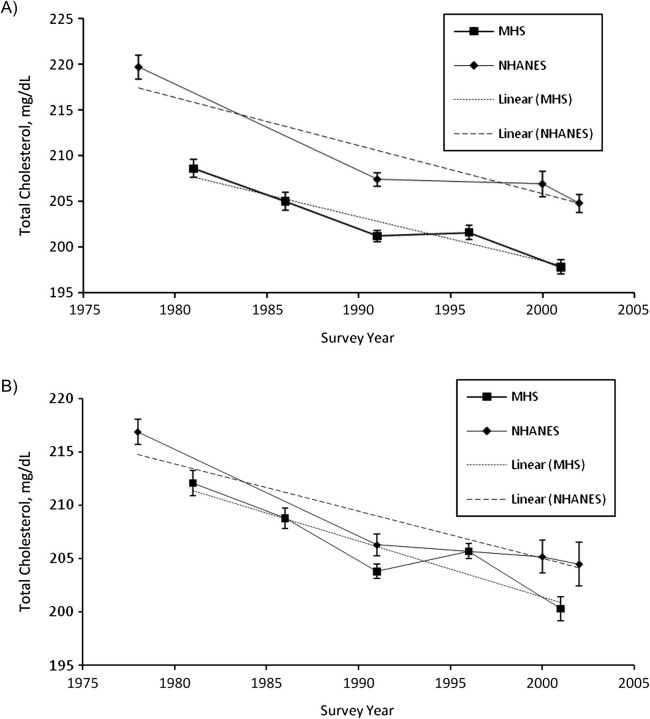

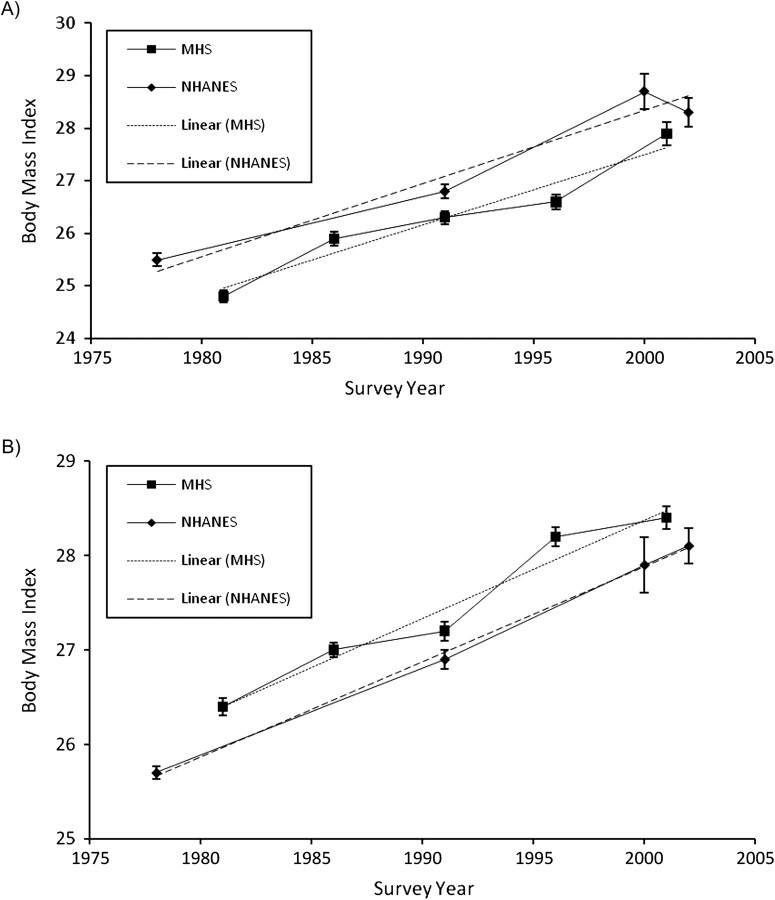

Trends in adverse CVD risk factors declined over 20 years in both surveys. The declines were similar in the 2 studies for women (Table 2 and Figures 1A and 2A) and men (Table 3 and Figures 1B and 2B). There were 2 exceptions. Systolic blood pressure in men declined faster in NHANES than in MHS, and obesity increased, although at a similar rate between the 2 studies (Figure 3). Energy intake significantly increased across survey years in all adults, except for men enrolled in MHS; however, total and saturated fat intake decreased over time.

Table 2.

Mean Levels and Prevalences of Cardiovascular Risk Factors Among Women Enrolled in the Minnesota Heart Survey (1980–2002) and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1976–2002)

| Characteristic | Survey and Range of Survey Years |

Difference |

|||||||||||||

| Minnesota Heart Survey |

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey |

||||||||||||||

| 1980–1982 | 1985–1987 | 1990–1992 | 1995–1997 | 2000–2002 | Slope | Ptrend | 1976–1980 | 1988–1994 | 1999–2000 | 2001–2002 | Slope | Ptrend | Slopediff | Pdiff | |

| Calendar yeara | 1981 | 1986 | 1991 | 1996 | 2001 | 1978 | 1991 | 2000 | 2002 | ||||||

| No. of subjects | 1,748 | 2,344 | 2,326 | 2,651 | 1,338 | 4,166 | 6,379 | 1,637 | 1,736 | ||||||

| Smoking, % | |||||||||||||||

| Current smoker | 30.9 | 24.6 | 22.6 | 17.5 | 17.2 | −0.7 | <0.001 | 34.3 | 25.9 | 21.6 | 22.5 | −0.5 | <0.001 | −0.22 | 0.02 |

| Former smoker | 22.4 | 26.8 | 25.3 | 28.2 | 25.9 | 0.19 | 0.003 | 14.9 | 21.9 | 21.7 | 21.4 | 0.23 | 0.008 | −0.04 | 0.71 |

| Never smoker | 46.7 | 48.6 | 52.1 | 54.3 | 56.9 | 0.53 | <0.001 | 50.8 | 52.2 | 56.7 | 56.1 | 0.27 | 0.006 | 0.26 | 0.05 |

| Daily nutrient intake | |||||||||||||||

| Energy, kcal | 1,656 | 1,672 | 1,689 | 1,786 | 1,782 | 7.25 | <0.001 | 1,484 | 1,763 | 1,875 | 1,856 | 15.31 | <0.001 | −7.95 | <0.001 |

| Total fat, % of kcal | 39 | 37 | 34 | 30 | 32 | −0.39 | <0.001 | 36 | 34 | 33 | 334 | −0.09 | <0.001 | −0.3 | <0.001 |

| Saturated fat, % of kcal | 14 | 13 | 12 | 10 | 11 | −0.17 | <0.001 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 11 | −0.07 | <0.001 | −0.1 | <0.001 |

| Clinical measures | |||||||||||||||

| Waist circumference, cm | N/A | N/A | 81.7 | 85.6 | 88.5 | 0.69 | <0.001 | N/A | 89.7 | 93.2 | 92.9 | 0.32 | <0.001 | 0.37 | 0.002 |

| Abdominal obesity, % | N/A | N/A | 26.8 | 36.5 | 43.3 | 1.67 | <0.001 | N/A | 47.9 | 58.2 | 58.6 | 1.03 | <0.001 | 0.64 | 0.01 |

| Body mass indexb group, % | |||||||||||||||

| <18.5 | 3.03 | 2.12 | 1.71 | 1.47 | 1.3 | −0.08 | <0.001 | 3.77 | 2.95 | 2.6 | 2.71 | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.19 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 57.7 | 50.9 | 48 | 41.3 | 38.5 | −0.97 | <0.001 | 52.4 | 43.9 | 33 | 34.4 | −0.84 | <0.001 | −0.14 | 0.31 |

| 25.0–29.9 | 25.1 | 27 | 29.2 | 30.8 | 28.9 | 0.26 | <0.001 | 26 | 26.3 | 28.4 | 28.9 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.21 |

| ≥30.0 | 14.1 | 19.9 | 21.1 | 26.4 | 31.3 | 0.79 | <0.001 | 17.8 | 26.9 | 36 | 33.9 | 0.74 | <0.001 | 0.05 | 0.64 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 73.7 | 72.8 | 75.5 | 72.5 | 71.4 | −0.08 | <0.001 | 80.3 | 72.8 | 71.6 | 71.9 | −0.32 | <0.001 | 0.23 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, % | 25.3 | 22.1 | 19.3 | 17.3 | 15.4 | −0.5 | <0.001 | 38.8 | 22.1 | 26.2 | 27 | −0.34 | <0.001 | −0.16 | 0.11 |

| Use of antihypertensive medication, % | 17.3 | 16.6 | 12.3 | 11.5 | 13.9 | −0.28 | <0.001 | 14.7 | 17.6 | 19.4 | 20.2 | 0.22 | 0.02 | −0.5 | <0.001 |

| High cholesterol, % | 23.3 | 21 | 19.9 | 22.2 | 19.8 | −0.09 | 0.2 | 33.3 | 32.5 | 31.6 | 28.7 | −0.16 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.5 |

| Use of cholesterol-lowering medication, % | 3.36 | 2.75 | 5.54 | 7.51 | 8.59 | 0.31 | <0.001 | N/A | 6.98 | 14 | 13.2 | 0.64 | <0.001 | −0.32 | <0.001 |

| No. of risk factorsc, % | |||||||||||||||

| 0 | 40.1 | 46.0 | 46.8 | 48.8 | 49.2 | 0.33 | <0.001 | 26.8 | 38.8 | 35.7 | 37.9 | 0.4 | <0.001 | 0.07 | 0.45 |

| 1 | 38.7 | 36.0 | 36.5 | 33.6 | 35.9 | 0.001 | 0.97 | 38.9 | 38.3 | 39.2 | 38.4 | −0.18 | 0.02 | −0.19 | 0.07 |

| 2 | 16.4 | 13.4 | 13.2 | 14.5 | 12.6 | −0.15 | 0.02 | 24.9 | 18.2 | 20.1 | 19.2 | −0.11 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.65 |

| 3–4 | 4.1 | 4.7 | 3.5 | 3.1 | 2.4 | −0.18 | <0.001 | 9.4 | 4.7 | 4.5 | 4.5 | −0.10 | <0.001 | 0.08 | 0.12 |

Abbreviation: N/A, not applicable.

Calendar year was the time variable used for a given survey in the regression model for each variable.

Weight (kg)/height (m)2.

The risk factor score included current smoking, obesity, hypertension, and high cholesterol.

Figure 1.

Trends in systolic blood pressure across survey years among A) women and B) men in the Minnesota Heart Survey (MHS; 1980–2002) (both P’s < 0.001) and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES; 1976–2002) (both P’s < 0.001). Systolic blood pressure decreased significantly over time in both surveys. However, rates of blood pressure change for women (panel A) were similar between surveys (Pdiff = 0.36), while for men (panel B), blood pressure decreased significantly faster in NHANES than in MHS (Pdiff = 0.01). Bars, standard error.

Figure 2.

Trends in serum total cholesterol level across survey years among A) women and B) men in the Minnesota Heart Survey (MHS; 1980–2002) (both P’s < 0.001) and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES; 1976–2002) (both P’s < 0.001). Serum total cholesterol levels decreased significantly over time in both surveys, but rates of change were similar between surveys for both genders (Pdiff = 0.58 and Pdiff = 0.56 for women and men, respectively). Bars, standard error.

Table 3.

Mean Levels and Prevalences of Cardiovascular Risk Factors Among Men Enrolled in the Minnesota Heart Survey (1980–2002) and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1976–2002)

| Characteristic | Survey and Range of Survey Years |

Difference |

|||||||||||||

| Minnesota Heart Survey |

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey |

||||||||||||||

| 1980–1982 | 1985–1987 | 1990–1992 | 1995–1997 | 2000–2002 | Slope | Ptrend | 1976–1980 | 1988–1994 | 1999–2000 | 2001–2002 | Slope | Ptrend | Slopediff | Pdiff | |

| Calendar yeara | 1981 | 1986 | 1991 | 1996 | 2001 | 1978 | 1991 | 2000 | 2002 | ||||||

| No. of subjects | 1,560 | 2,186 | 2,160 | 2,359 | 1,193 | 3,551 | 5,698 | 1,494 | 1,649 | ||||||

| Smoking, % | |||||||||||||||

| Current smoker | 31.1 | 25.9 | 22.6 | 20 | 17.5 | −0.66 | <0.001 | 43.3 | 32.6 | 28.3 | 27.1 | −0.64 | <0.001 | −0.02 | 0.82 |

| Former smoker | 38.3 | 38.4 | 35.9 | 31.9 | 31 | −0.44 | <0.001 | 32.5 | 33.8 | 31.2 | 28.4 | −0.19 | 0.01 | −0.25 | 0.009 |

| Never smoker | 30.6 | 35.7 | 41.4 | 48 | 51.5 | 1.1 | <0.001 | 24.2 | 33.6 | 40.4 | 44.6 | 0.83 | <0.001 | 0.27 | 0.01 |

| Daily nutrient intake | |||||||||||||||

| Energy, kcal | 2,500 | 2,563 | 2,509 | 2,532 | 2,488 | −1.66 | 0.44 | 2,407 | 2,651 | 2,622 | 2,675 | 8.44 | <0.001 | −10.03 | 0.003 |

| Total fat, % of kcal | 40 | 39 | 35 | 31 | 33 | −0.41 | <0.001 | 37 | 34 | 33 | 34 | −0.14 | <0.001 | −0.28 | <0.001 |

| Saturated fat, % of kcal | 15 | 14 | 13 | 11 | 11 | −0.18 | <0.001 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 11 | −0.1 | <0.001 | −0.07 | <0.001 |

| Clinical measures | |||||||||||||||

| Waist circumference, cm | N/A | N/A | 95.4 | 99.3 | 99.5 | 0.45 | <0.001 | N/A | 96.4 | 99.2 | 99.8 | 0.31 | <0.001 | 0.14 | 0.05 |

| Abdominal obesity, % | N/A | N/A | 25.8 | 39.5 | 38.2 | 1.42 | <0.001 | N/A | 29.8 | 36.9 | 39.8 | 0.87 | <0.001 | 0.56 | 0.02 |

| Body mass indexb group, % | |||||||||||||||

| <18.5 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.14 | 0.16 | −0.02 | 0.009 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 0.7 | −0.01 | 0.52 | −0.01 | 0.32 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 34.4 | 32.3 | 30.3 | 19.7 | 23.9 | −0.75 | <0.001 | 44.9 | 36 | 30.6 | 27.5 | −0.7 | <0.001 | −0.05 | 0.61 |

| 25.0–29.9 | 49.7 | 47.9 | 47.9 | 49.5 | 44.2 | −0.14 | 0.07 | 41.2 | 42.2 | 40.6 | 43.4 | 0.04 | 0.62 | −0.18 | 0.12 |

| ≥30.0 | 15.2 | 19.6 | 21.5 | 30.7 | 31.8 | 0.91 | <0.001 | 12.5 | 21 | 27.4 | 28.4 | 0.67 | <0.001 | 0.24 | 0.007 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 77.9 | 76.9 | 79.9 | 77.6 | 76.06 | −0.03 | 0.16 | 84.2 | 77.7 | 75.9 | 74.6 | −0.36 | <0.001 | 0.33 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, % | 28.5 | 25.6 | 27.9 | 24.9 | 16.1 | −0.43 | <0.001 | 47.9 | 24.9 | 27.9 | 24.9 | −0.71 | <0.001 | 0.27 | 0.03 |

| Use of antihypertensive medication, % | 15.2 | 13.9 | 13.6 | 13.3 | 13.6 | −0.08 | 0.15 | 9.66 | 15.2 | 18.2 | 16.3 | 0.29 | <0.001 | −0.37 | <0.001 |

| High cholesterol, % | 23.5 | 21.7 | 21.1 | 23.2 | 25.3 | 0.09 | 0.19 | 28.7 | 31.6 | 34.7 | 33.9 | 0.24 | 0.002 | −0.15 | 0.12 |

| Use of cholesterol-lowering medication, % | 4.3 | 4.1 | 6.1 | 9.6 | 14.1 | 0.48 | <0.001 | N/A | 7.1 | 16.9 | 18.1 | 1.03 | <0.001 | −0.55 | <0.001 |

| No. of risk factorsc, % | |||||||||||||||

| 0 | 38.6 | 42.0 | 42.4 | 41.1 | 46.0 | 0.53 | <0.001 | 21.0 | 35.5 | 34.8 | 37.1 | 0.23 | 0.01 | −0.3 | 0.02 |

| 1 | 37.8 | 36.8 | 36.3 | 36.8 | 38.3 | 0.08 | 0.29 | 39.6 | 41.3 | 43.2 | 40.6 | 0.01 | 0.94 | −0.07 | 0.47 |

| 2 | 18.7 | 16.0 | 16.8 | 17.0 | 14.5 | −0.39 | <0.001 | 29.9 | 18.3 | 17.9 | 18.5 | −0.12 | 0.04 | 0.27 | 0.002 |

| 3–4 | 4.9 | 5.2 | 4.5 | 5.1 | 1.3 | −0.21 | <0.001 | 9.5 | 4.8 | 4.1 | 3.7 | −0.12 | <0.001 | 0.09 | 0.03 |

Abbreviation: N/A, not applicable.

Calendar year was the time variable used for a given survey in the regression model for each variable.

Weight (kg)/height (m)2.

The risk factor score included current smoking, obesity, hypertension, and high cholesterol.

Figure 3.

Trends in body mass index (weight (kg)/height (m)2) across survey years among A) women and B) men in the Minnesota Heart Survey (MHS; 1980–2002) (both P’s < 0.001) and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES; 1976–2002) (both P’s < 0.001). Body mass index increased significantly over time in both surveys, but rates of change were similar between surveys for both genders (Pdiff = 0.76 and Pdiff = 0.83 for women and men, respectively). Bars, standard error.

Lower levels of CHD risk factors in MHS

Since the annual rates of decline were similar for each risk factor, we compared overall risk factor levels between the 2 surveys in women and in men. Generally, MHS women had a better CVD risk factor profile than women in NHANES (Table 4). Although the men in MHS had a higher body mass index (weight (kg)/height (m)2) than those enrolled in NHANES, Minnesotans had a smaller waist circumference, lower blood pressure and total cholesterol, and lower prevalences of smoking, hypertension, and high cholesterol than men in NHANES (Table 5). Because of a faster rate of decline, the general difference in systolic blood pressure in men between the studies disappeared by 2000.

Table 4.

Differences in Age-Adjusted Cardiovascular Risk Factor Levels Among Women Enrolled in the Minnesota Heart Survey (1980–2002) and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1976–2002)

| Risk Factor | Fitted Mean Value |

Mean Differencea | P Valueb | |

| NHANES | MHS | |||

| Smoking, % | 25.4 | 21.3 | −4.1 | <0.001 |

| Mean BMIc | 27.3 | 26.6 | −0.7 | <0.001 |

| BMI group, % | ||||

| <18.5 | 2.9 | 1.8 | −1.1 | <0.001 |

| 18.5–<25 | 40.8 | 45.3 | 4.5 | <0.001 |

| 25–<30 | 27.3 | 28.7 | 1.4 | 0.03 |

| ≥30 | 29.0 | 24.2 | −4.8 | <0.001 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 91.3 | 83.3 | −8.0 | <0.001 |

| Abdominal obesity, % | 53.1 | 31.8 | −21.3 | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 120.8 | 117.1 | −3.7 | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 73.4 | 72.3 | −1.1 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, % | 18.4 | 11.2 | −7.2 | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 208.4 | 201.5 | −6.9 | <0.001 |

| High cholesterol level, % | 21.7 | 16.0 | −5.7 | <0.001 |

| No. of risk factorsd, % | ||||

| 0 | 36.3 | 47.3 | 11.0 | <0.001 |

| 1 | 38.6 | 36.1 | −2.5 | 0.003 |

| 2 | 19.9 | 13.6 | −6.3 | <0.001 |

| 3–4 | 5.3 | 3.1 | −2.2 | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; MHS, Minnesota Heart Survey; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Average difference in 1990 for the estimated level of the risk factor (a negative value means that the MHS value was lower), based on fitting a linear model for change within MHS and within NHANES and comparing these 2 lines at 1990.

Test of the null hypothesis that the difference in mean levels between NHANES and MHS was 0.

Weight (kg)/height (m)2.

The risk factor score included current smoking, obesity, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol.

Table 5.

Differences in Age-Adjusted Cardiovascular Risk Factor Levels Among Men Enrolled in the Minnesota Heart Survey (1980–2002) and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1976–2002)

| Risk Factor | Fitted Mean Value |

Mean Differencea | P Valueb | |

| NHANES | MHS | |||

| Smoking, % | 31.7 | 21.5 | −10.2 | <0.001 |

| Mean BMIc | 27.3 | 27.7 | 0.4 | <0.001 |

| BMI group, % | ||||

| <18.5 | 1.0 | 0.2 | −0.8 | <0.001 |

| 18.5–<25 | 34.0 | 25.9 | −8.1 | <0.001 |

| 25–<30 | 42.0 | 48.4 | 6.4 | 0.03 |

| ≥30 | 23.0 | 25.5 | 2.5 | <0.001 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 98.0 | 90.6 | −7.4 | <0.001 |

| Abdominal obesity, % | 34.1 | 31.9 | −2.2 | 0.14 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 124.7 | 122.7 | −2.0 | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 77.4 | 76.5 | −0.9 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, % | 21.7 | 15.4 | −6.3 | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 207.0 | 205.0 | −2.0 | 0.01 |

| High cholesterol level, % | 19.7 | 17.0 | −2.7 | <0.001 |

| No. of risk factorsd, % | ||||

| 0 | 33.9 | 43.6 | 9.7 | <0.001 |

| 1 | 41.4 | 37.4 | −4.0 | <0.001 |

| 2 | 19.7 | 15.3 | −4.4 | <0.001 |

| 3–4 | 5.0 | 3.7 | −1.3 | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; MHS, Minnesota Heart Survey; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Average difference in 1990 for the estimated level of the risk factor (a negative value means that the MHS value was lower), based on fitting a linear model for change within MHS and within NHANES and comparing these 2 lines at 1990.

Test of the null hypothesis that the difference in mean levels between NHANES and MHS was 0.

Weight (kg)/height (m)2.

The risk factor score included current smoking, obesity, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol.

We created a risk factor score representing the number of adverse risk factors for individuals, including current smoking, obesity, hypertension, and high cholesterol. Significantly greater proportions of men and women in MHS than in NHANES had no risk factors (men: 44% vs. 34%; women: 47% vs. 36%) (Tables 4 and 5). Furthermore, greater proportions of men and women in NHANES than in MHS had 2 or more risk factors.

The majority of persons participating in MHS (1995–1997 and 2000–2002) and NHANES (1999–2002) reported having some type of health insurance, including private or government-sponsored insurance. However, more Minnesotans were covered (93.1%–96.7%) than members of the US general population (80.0%–84.8%).

In subgroup analysis, data were examined without the inclusion of racial/ethnic minority groups. Study results were similar for analyses of Caucasians only.

DISCUSSION

The ecologic data presented here suggest that both CHD mortality rates and CHD risk factor levels were decreasing continuously during the study period in both Minnesota and the United States as a whole, with Minnesota generally being at a lower level. According to both MHS and NHANES findings, the patterns of most CVD risk factors have improved over the past 25 years, with a lower overall CVD risk profile in Minnesotans. More adults in MHS than in NHANES were free of adverse CVD risk factors or had only 1 CVD risk factor. Smoking, known to increase CHD risk at least 2-fold, was lower among women and men in MHS than in the general US population, even though these rates have been on the decline in both populations. As previously reported by MHS investigators, systolic and diastolic blood pressure levels and serum total cholesterol concentrations have declined over the past 2 decades, despite increasing rates of obesity (10, 11, 21–23). Notably, the prevalences of hypertension and high cholesterol were lower across survey years among MHS adults than in the US general population, even though there was no significant difference in the rate of their declining survey trends.

Declining trends in CHD mortality and CHD risk factors

Interpretation of the relation between CHD mortality rate trends and the risk factor trends reported in this paper is limited. First, the Minnesota and national CHD mortality trends have been continuous, with little change in slope for many years and with Minnesota rates generally being lower than national rates. Second, risk factor levels declined both in Minnesota and nationally, generally at similar rates (contrary to our hypothesis that risk factors would be declining faster in Minnesota than nationally), again with Minnesotans generally having lower risk. Because there was no clear change of slope in the CHD mortality curve and because the number of surveys was small, it was not possible to perform an analysis of lag time between risk factor change and CHD mortality change. However, the pattern of decline in mortality and risk factors between Minnesota and the nation overall is consistent with a role for declining CHD risk factor levels in determining a decline in CHD mortality. Investigators who have modeled risk factors and CVD mortality in prospective studies have attributed the decline in CHD mortality, in part, to reductions in the modifiable CVD risk factors (4, 22). For example, investigators from the British Regional Heart Study concluded that 46% of the decline in incident myocardial infarction over 25 years among men could be explained by reduced prevalence of smoking and improved levels of blood pressure, high density lipoprotein cholesterol, and non-high density lipoprotein cholesterol (22). Although blood pressure and lipid levels were not measured in the Nurses’ Health Study, a decline in incident CHD among women was attributed to reduced smoking, decreased saturated fat intake, increased fiber intake, and hormone replacement therapy, even in women who gained weight (24).

Declining levels of CVD risk factors

Our cross-sectional observation of declining trends in CVD risk factor levels is generally consistent with prospective studies, which have observed trends of improving CVD risk factors (2, 22, 24–28), except body weight (29, 30). Normal-weight and obese middle-aged men and women who maintained their weight over 9 years of follow-up had improved blood pressure and lipid levels, and in this study, the change was not due to medication use (31). However, excessive weight gain over 9 years was associated with unfavorable changes in CVD risk factors. In the Framingham Heart Study, from 1970 to 2005, blood pressure and cholesterol levels improved in adults regardless of diabetes status, although many were treated with medication (32). Unlike other CVD risk factors, the prevalences of overweight and obesity (body mass index ≥25) and abdominal obesity have been on the rise since the 1980s; the latter is thought to better predict CVD risk through its relation with insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome (5, 6, 33–35). Despite the greater prevalence of obesity in MHS men than in NHANES men, waist circumference and abdominal obesity were consistently lower in MHS than in NHANES across survey years. Higher educational achievement and better eating patterns may also explain the better CVD risk profile among Minnesotans (25, 36).

Despite these generally promising trends, hypertension and dyslipidemia remain a burden among US adults (37–40), which may be due in part to disparities in diagnosis, management, and treatment among race/ethnicity, gender, and age groups (26, 41–44). In subgroup analysis, however, findings among Caucasians in MHS and NHANES were similar to those observed in the primary analysis, which included minority participants.

Few studies have compared CVD risk factor trends among regional and national samples. Using data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) (45), Greenlund et al. (46) demonstrated an increased prevalence of multiple CHD risk factors in the 1990s. Although CHD risk factor levels declined in our NHANES data, this inconsistency between studies may be due to the self-report nature of data collected in the BRFSS, a telephone-based surveillance system, as compared with the objectively measured CVD risk factors in NHANES. The observed increases in multiple CVD risk factors, however, may actually reflect increases in awareness of CVD risk factors, although Greenlund et al. claimed that the BRFSS estimates were comparable to NHANES estimates for some CVD risk factors (46).

Limitations of the present study include the separate surveillance systems. NHANES and MHS use different measurement methods and sampling strategies, which have been described elsewhere (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm; 11). For example, the method of measuring blood pressure changed over time, despite the overlap in study periods and corrective adjustments (11). Only 1 self-report, 24-hour dietary recall was used in each study, which may not represent usual dietary intake. Thus, misclassification of nutrient intake may exist in both studies, but misclassification is likely to be similar for both. Some differences in MHS and NHANES participants may be related to age and race/ethnicity, though all analyses were adjusted for age and stratified by gender. The results of subgroup analyses were consistent with those of the primary analyses, suggesting that differences in race/ethnicity had a minimal effect on the results.

The strengths of this study include the comparison of 2 large population-based surveys, each using probabilistic methods to represent a target geographic area, of the secular trends in CVD risk factors in which much attention was given to quality control of the measurements. The 2 studies had similar designs, including the use of population-based serial cross-sectional surveys. Rarely have studies been conducted to describe and compare the levels of multiple risk factors across populations over long time periods. In addition, with inclusion of laboratory and clinic assessments in both MHS and NHANES, misclassification is probably smaller than in other surveillance studies, such as the BRFSS, where participants are asked to report their own weight, blood pressure, and cholesterol status (45).

These findings of a better CVD risk factor profile are consistent with Minnesota's lower rates of CHD. Earlier reports provided evidence of improved cardiac disease prevalence through downward trends in hospitalization rates for CHD, congestive heart failure, and stroke (21, 47, 48). Hospitalization rates are substantially lower in Minnesota than in the US generally (47). Another potential explanation for favorable outcomes may be the high quality of health care in Minnesota (49). Thus, we have demonstrated that Minnesota's lower rates of CHD may be explained by better CVD risk factor profiles and, we surmise, greater access to high-quality health care as well (50).

Acknowledgments

Author affiliations: Division of Epidemiology and Community Health, School of Public Health, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota (Huifen Wang, Lyn M. Steffen, David R. Jacobs, Xia Zhou, Henry Blackburn, Alan K. Berger, Kristian B. Filion, Russell V. Luepker); and Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota (Alan K. Berger).

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 HL023727 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BRFSS

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

- CHD

coronary heart disease

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- MHS

Minnesota Heart Survey

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

References

- 1.National Center for Health Statistics. Health Data Interactive. Mortality by Underlying and Multiple Cause, Ages 18 +: US, 1981–2007 (Source: NVSS) [table] Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2010. ( http://205.207.175.93/HDI/TableViewer/tableView.aspx?ReportId=166). (Accessed July 10, 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119(3):e21–e181. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ezzati M, Oza S, Danaei G, et al. Trends and cardiovascular mortality effects of state-level blood pressure and uncontrolled hypertension in the United States. Circulation. 2008;117(7):905–914. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.732131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB, et al. Explaining the decrease in U.S. deaths from coronary disease, 1980–2000. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(23):2388–2398. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa053935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Després JP, Arsenault BJ, Côté M, et al. Abdominal obesity: the cholesterol of the 21st century? Can J Cardiol. 2008;24(suppl D):7D–12D. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(08)71043-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Institutes of Health. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults—the evidence report. Obes Res. 1998;6(suppl 2):S51–S209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lichtenstein AH, Appel LJ, Brands M, et al. Diet and lifestyle recommendations revision 2006: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Nutrition Committee. Circulation. 2006;114(1):82–96. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.176158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hajjar I, Kotchen TA. Trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the United States, 1988–2000. JAMA. 2003;290(2):199–206. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muntner P, He J, Cutler JA, et al. Trends in blood pressure among children and adolescents. JAMA. 2004;291(17):2107–2113. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.17.2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnett DK, Jacobs DR, Jr, Luepker RV, et al. Twenty-year trends in serum cholesterol, hypercholesterolemia, and cholesterol medication use: the Minnesota Heart Survey, 1980–1982 to 2000–2002. Circulation. 2005;112(25):3884–3891. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.549857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luepker RV, Arnett DK, Jacobs DR, Jr, et al. Trends in blood pressure, hypertension control, and stroke mortality: the Minnesota Heart Survey. Am J Med. 2006;119(1):42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. NHANES Response Rates and CPS Totals [data set] Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2010. ( http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/response_rates_CPS.htm). (Accessed August 29, 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Public Health Service. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification: ICD-9-CM. Vol 1. Washington, DC: US GPO; 1980. US Department of Health and Human Services. (DHHS publication no. (PHS) 80-1260) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edlavitch SA, Baxter J. Comparability of mortality follow-up before and after the National Death Index. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;127(6):1164–1178. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Physician Examination Procedures Manual. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2003. ( http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_03_04/PE.pdf). (Accessed August 29, 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allain CC, Poon LS, Chan CS, et al. Enzymatic determination of total serum cholesterol. Clin Chem. 1974;20(4):470–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Center for Health Statistics. Survey Design Factors. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2009. NHANES I Web Tutorial. ( http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/tutorials/nhanes/surveydesign/intro_I.htm). (Accessed August 29, 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection. Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106(25):3143–3421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42(6):1206–1252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pilote L, Dasgupta K, Guru V, et al. A comprehensive view of sex-specific issues related to cardiovascular disease. CMAJ. 2007;176(6):S1–S44. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Center for Health Statistics. Health Data Interactive [table] Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2010. ( http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hdi.htm). (Accessed August 29, 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hardoon SL, Whincup PH, Lennon LT, et al. How much of the recent decline in the incidence of myocardial infarction in British men can be explained by changes in cardiovascular risk factors? Evidence from a prospective population-based study. Circulation. 2008;117(5):598–604. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.705947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gregg EW, Cheng YJ, Cadwell BL, et al. Secular trends in cardiovascular disease risk factors according to body mass index in US adults. JAMA. 2005;293(15):1868–1874. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.15.1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, et al. Trends in the incidence of coronary heart disease and changes in diet and lifestyle in women. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(8):530–537. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008243430802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bartley M, Fitzpatrick R, Firth D, et al. Social distribution of cardiovascular disease risk factors: change among men in England 1984–1993. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000;54(11):806–814. doi: 10.1136/jech.54.11.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Psaty BM, Manolio TA, Smith NL, et al. Time trends in high blood pressure control and the use of antihypertensive medications in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(20):2325–2332. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.20.2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clarke R, Emberson J, Fletcher A, et al. Life expectancy in relation to cardiovascular risk factors: 38 year follow-up of 19,000 men in the Whitehall study. BMJ. 2009;339 doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3513. b3513. (doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3513) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Szklo M, Chambless LE, Folsom AR, et al. Trends in plasma cholesterol levels in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Prev Med. 2000;30(3):252–259. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monda KL, Ballantyne CM, North KE. Longitudinal impact of physical activity on lipid profiles in middle-aged adults: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(8):1685–1691. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P900029-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Norman JE, Bild D, Lewis CE, et al. The impact of weight change on cardiovascular disease risk factors in young black and white adults: the CARDIA Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27(3):369–376. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Truesdale KP, Stevens J, Cai J. Nine-year changes in cardiovascular disease risk factors with weight maintenance in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(8):890–900. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Preis SR, Pencina MJ, Hwang SJ, et al. Trends in cardiovascular disease risk factors in individuals with and without diabetes mellitus in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2009;120(3):212–220. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.846519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haffner SM. Abdominal adiposity and cardiometabolic risk: do we have all the answers? Am J Med. 2007;120(9 suppl 1):S10–S16. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Folsom AR, Kaye SA, Sellers TA, et al. Body fat distribution and 5-year risk of death in older women. JAMA. 1993;269(4):483–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee CM, Huxley RR, Wildman RP, et al. Indices of abdominal obesity are better discriminators of cardiovascular risk factors than BMI: a meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(7):646–653. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elmer PJ, Obarzanek E, Vollmer WM, et al. Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on diet, weight, physical fitness, and blood pressure control: 18-month results of a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(7):485–495. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-7-200604040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muntner P, Krousel-Wood M, Hyre AD, et al. Antihypertensive Prescriptions for Newly Treated Patients Before and After the Main Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial results and seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure guidelines. Hypertension. 2009;53(4):617–623. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.120154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siegel D, Lopez J, Meier J. Use of cholesterol-lowering medications in the United States from 1991 to 1997. Am J Med. 2000;108(6):496–499. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00319-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hyre AD, Muntner P, Menke A, et al. Trends in ATP-III-defined high blood cholesterol prevalence, awareness, treatment and control among U.S. adults. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(7):548–555. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goff DC, Jr, Bertoni AG, Kramer H, et al. Dyslipidemia prevalence, treatment, and control in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA): gender, ethnicity, and coronary artery calcium. Circulation. 2006;113(5):647–656. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.552737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hendrix KH, Riehle JE, Egan BM. Ethnic, gender, and age-related differences in treatment and control of dyslipidemia in hypertensive patients. Ethn Dis. 2005;15(1):11–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clark LT, Maki KC, Galant R, et al. Ethnic differences in achievement of cholesterol treatment goals. Results from the National Cholesterol Education Program Evaluation Project Utilizing Novel E-Technology II. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(4):320–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00349.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nau DP, Mallya U. Sex disparity in the management of dyslipidemia among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in a managed care organization. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11(2):69–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O'Meara JG, Kardia SL, Armon JJ, et al. Ethnic and sex differences in the prevalence, treatment, and control of dyslipidemia among hypertensive adults in the GENOA Study. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(12):1313–1318. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.12.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Prevalence and Trends Data [database] Atlanta, GA: National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; 2009. ( http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/brfss/). (Accessed June 23, 2009) [Google Scholar]

- 46.Greenlund KJ, Zheng ZJ, Keenan NL, et al. Trends in self-reported multiple cardiovascular disease risk factors among adults in the United States, 1991–1999. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(2):181–188. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McGovern PG, Pankow JS, Shahar E, et al. Recent trends in acute coronary heart disease—mortality, morbidity, medical care, and risk factors. The Minnesota Heart Survey Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(14):884–890. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199604043341403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Minnesota Department of Health. Heart Disease and Stroke in Minnesota: 2007 Burden Report. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Department of Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Department of Health and Human Services. 2006 State Snapshots. Based on Data Collected for the National Healthcare Quality Report (NHQR) Minnesota. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2007. Executive summary. i–iii. ( http://statesnapshots.ahrq.gov/snaps06/download/MN_2006_Snapshots.pdf). (Accessed January 4, 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 50.McWilliams JM, Meara E, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Differences in control of cardiovascular disease and diabetes by race, ethnicity, and education: U.S. trends from 1999 to 2006 and effects of Medicare coverage. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(8):505–515. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-8-200904210-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]