Abstract

Objectives

The aim of patient information is to involve patients in their condition and their treatment. The literature states that good information can improve medical outcomes, reduce patient anxiety and that patients want access to it. We wanted to calculate the provision of written patient information to ENT day-case patients, measure information recall and patient satisfaction.

Design

A prospective audit cycle. The first cycle of the audit studied patients receiving current practice, where verbal information was provided but written patient information was not routine. Following a departmental drive towards provision of written patient information, a second cycle was audited. A questionnaire on admission to the ward on the day of surgery was used to measure outcomes.

Setting

The ENT Department of a UK university teaching hospital.

Main outcome measures

The number of patients receiving written patient information, the rate of recall of complications and patient satisfaction with the information provided.

Participants

One hundred patients undergoing day-case surgery were included. The first cycle of the audit studied 50 consecutive patients, receiving current practice. The second cycle, following implementation of change, studied a further 50 consecutive patients.

Results

Following a departmental drive towards provision of patient information, 64% of patients received written patient information improving the rate of recall of the majority of complications from 24% to 52%. There was no significant difference in patient satisfaction between groups.

Conclusions

Written patient information leaflets are a useful tool to improve recall of information given to patients, in order to facilitate informed consent.

Introduction

The aim of patient information is to involve patients in their condition and their treatment. Information is an important part of the patient journey. It is central to the overall quality of each patient's experience.

The Department of Health published a Health Service Circular entitled Good Practice in Consent1 in response to the NHS plan of achieving a patient-centred consent practice in the UK. Following this publication, NHS Trusts were urged to provide patients with written information about their treatment, to back up verbal information, although NHS organizations remain responsible for satisfying themselves as to the quality and accuracy of the information that they provide to patients.

The thought of having an operation can be frightening for anyone. Patient information may help the patient and the medical team. By understanding ‘why’ and ‘what’ is happening, the patient can become actively involved. Patients have the right to quality care and to share in the decisions on how best to solve health problems.

By providing good patient information, we can help to make sure that patients arrive on time and are properly prepared for procedures or operations, it will serve to remind patients what their doctor has told them if, due to stress or language difficulties, they are unable to remember. Patient information enables people to make informed decisions, giving them time to go away, read the information that is relevant to them, and think about the issues involved.

The literature states that good information can improve medical outcomes2 and reduce patient anxiety,3 and that patients want access to it.4 In our institution we aimed to determine whether patients undergoing day-case surgery were being provided with written information. We wanted to evaluate patient satisfaction with current patient information. As an objective measure of the use of patient information we wanted to assess recall of surgical complications on the day of surgery. A prospective audit of preoperative patient information in an English otolaryngology unit before and after a departmental drive to provide patient information is described.

Methods

During the first four months of 2009, a prospective controlled study was conducted in the ENT Department of a UK university teaching hospital. We carried out a prospective audit of 100 patients undergoing day-case surgery. The first cycle involved 50 consecutive patients receiving current practice. Verbal information including risks was provided but provision of written patient information was not mandatory.

Following completion of the first audit cycle, the results were presented to the department. All clinicians and nursing staff involved in consenting and listing patients for surgery were emailed and contacted personally. The published benefits of good patient information were conveyed and all members of the team were encouraged to supply, patients undergoing surgery, information leaflets. We then studied another 50 consecutive patients in cycle 2.

This prospective audit of practice was conducted during the first four months of 2009 in the ENT Department of a UK University Teaching Hospital. Questionnaires on admission to the ward on the day of surgery were used to gather data and were completed by patients and collected by the medical team. In all patients the following outcomes were measured: if written patient information had been received, recall of complications, and satisfaction with information received. Other information collected included demographics, procedure type, the time between consent and procedure and whether patients found written information beneficial.

Results

There were differences between cycles 1 and 2. Following our departmental drive, patient information had been received more often, recall of complications improved and patient satisfaction remained good. Sample sizes were too small for the results to be deemed statistically significant.

Eleven clinicians were involved in this process (seven consultants, four specialist registrars). A total of 50 patients were studied in each cycle, there were 4 weeks between cycles. As evident from Table 1, the first cycle revealed equal numbers of male and female respondents while in the second cycle female patients made the slight majority of 54%.

Table 1.

Gender

| Gender | Cycle 1 (n) | Cycle 1 (%) | Cycle 2 (n) | Cycle 2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 25 | 50 | 23 | 46 |

| Women | 25 | 50 | 27 | 54 |

The respondents were divided into three groups according to age. Those under 16 years of age were those of paediatric admissions for day-case surgery where their parents or guardians were interviewed regarding their satisfaction of information received. As indicated in Table 2, this group made up 24% of respondents in the first cycle and 20% in the second cycle. The largest group were those in the age range 17–60 years. The remaining respondents were those aged more than 60 years.

Table 2.

Age

| Age (years) | Cycle 1 (n) | Cycle 1 (%) | Cycle 2 (n) | Cycle 2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <16 | 12 | 24 | 10 | 20 |

| 17–60 | 27 | 54 | 26 | 52 |

| >60 | 11 | 22 | 14 | 28 |

Table 3 indicates that types of ENT day-case surgery were grossly divided into four different categories for comparison. These were operations involving the ear or mastoid region, those involving the nasal or sinus region, those of the throat or neck area and lastly operations that involved more than one area on the same day. The majority of day cases involved throat or neck procedures, 44% of cases in cycle 1 and 32% in cycle 2. Only 6% of cases in both cycles were procedures involving more than one head and neck site.

Table 3.

Procedure type

| Type of procedure | Cycle 1 (n) | Cycle 1 (%) | Cycle 2 (n) | Cycle 2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ear/Mastoid surgery | 10 | 20 | 15 | 30 |

| Nasal/Sinus surgery | 15 | 30 | 16 | 32 |

| Throat/Neck surgery | 22 | 44 | 16 | 32 |

| More than one type of surgery | 3 | 6 | 3 | 6 |

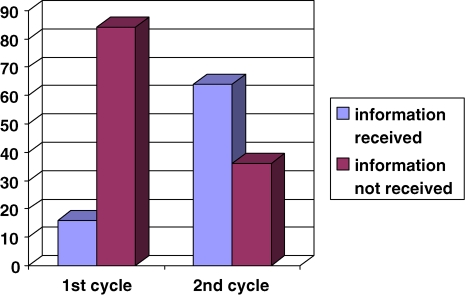

As illustrated in Figure 1, there was a dramatic increase in the number of patients receiving written information regarding their day-case surgery after the first cycle of this audit. From a mere 16%, this number improved to 64%.

Figure 1.

Provision of written information

As evident from Table 4, most patients perceived written information as being beneficial in helping them in the understanding of their surgery and most importantly, the risks associated with the procedures. Both cycles showed a consistent response with 82% in cycle one and 80% in cycle 2 where respondents agreed that written information was helpful. However 8% of patients in cycle 2 felt that the written information they received did not help them further in understanding what their operation was about, compared to 0% in cycle 1. There were also a group of patients (18% in cycle 1 and 12% in cycle 2) that felt indifferent about the advantages of being given written information.

Table 4.

Written patient information benefit

| Written patient information beneficial? | Cycle 1 (n) | Cycle 1 (%) | Cycle 2 (n) | Cycle 2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 41 | 82 | 40 | 80 |

| No | 0 | 0 | 4 | 8 |

| Indifferent | 9 | 18 | 6 | 12 |

Duration between consent and surgery was also assessed to determine whether this had a bearing on recall rates of complications among patients. Table 5 illustrates that the majority of day-case operations in cycle 1 of the audit were procedures occurring less than 1 month after consent. In cycle 2, this was made up of procedures occurring less than 3 months from the consent process. Only 2% of cases in cycle 2 were those occurring after 3 months of consent.

Table 5.

Duration between consent and surgery

| Time | Cycle 1 (n) | Cycle 1 (%) | Cycle 2 (n) | Cycle 2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 week | 13 | 26 | 10 | 20 |

| <1 month | 25 | 50 | 15 | 30 |

| <3 months | 12 | 24 | 24 | 48 |

| >3 months | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

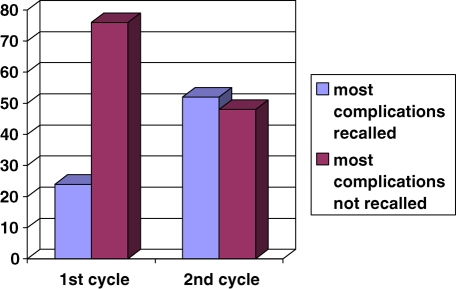

Figure 2 describes the improvement in recall of half or more of the complications of surgery from 24% to 52%. In cycle 1 a staggering 70% of respondents were unable to remember a single complication associated with their surgery, even though majority of cases occurred within a week on the consent process. Cycle 2 of the audit saw an improvement in this number after written information was routinely given out during the consent process along with verbal information, with 26% if patients unable to remember any risks associated with their operation.

Figure 2.

Recall of complications

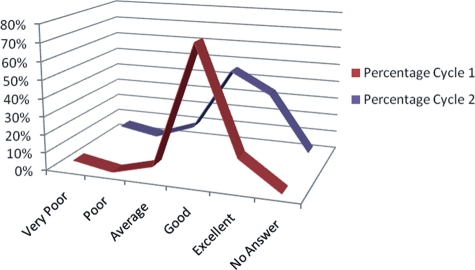

Figure 3 indicates a trend towards greater patient satisfaction in cycle 2 with more patients in the excellent group, 34%, compared to 16% in cycle 1, however, this is not statistically significant.

Figure 3.

Overall satisfaction with information received

Discussion and conclusion

Our audit has shown that the practice of providing written information to this group of patients during the consent procedure improved recall rates of complications and patient satisfaction with information provision.

The limitations to this study were the small number of patients, 100 patients included in both cycles of the audit. In an audit such as this we are not able to tease out all the factors contributing to recall ability such as literacy rates. Other potential variables also included patient education level, ethnicity, motivation for information and time spent in consultation. We were not assessing overall satisfaction with the surgical experience which would include hospital stay, helpfulness of staff, car-parking, availability of convenient and early dates for surgery, we looked solely at written patient information. A more in depth study, using a qualitative approach, may help answer these questions, as well as a standardization of practice where all the clinicians involved agree to a fixed list of complications to be explained depending on type of procedure.

Individual and group discussions may have been helpful to investigate why certain patients found not receiving information to be beneficial. There were also a group of patients, 18% in cycle 1 and 12% in cycle 2, that felt indifferent about the advantages of being given written information. One particular respondent in this group commented ‘ignorance is bliss’.

There has been an improvement in the rate of patient information provided. The first audit cycle discovered that only a small percentage of patients were receiving written information as written information was not readily available in clinics, patients were not offered or did not specifically request for them and giving of written information was not effectively conducted due to lack of agreed local protocols. One-third of patients in the second cycle however still did not receive written information. This was due, in part, to personal attitudes when patients had declined such information or preferred to look up information themselves from other sources. Information sheets were not available for certain, rarely performed, procedures. Satisfaction with information received suggests an improvement. Recall of risk factors is better when written information is given.

Many patients were not being given written information. The commonest practice prior to this study was, provision of oral information only, most patients felt additional written information to be beneficial. With the relatively simple change in practice, giving written information in clinic during consent and re-auditing practice, very poor recall rates were improved, despite no significant difference in patient satisfaction.

Written information is beneficial and should be provided in a systematic way. Patient information leaflets are a useful tool for the surgeon to improve recall of the information given to the patient, in order to facilitate informed consent. This is important as an effort of spreading information and also for prevention of litigation. However, all patients do not experience the written information in the same way. What we think is in the best interests of the patient does not necessarily increase patient satisfaction and we encourage patients to have their say and provide the medical profession with information.

Following this audit it is the aim of the department to ensure written information is available and given to all patients undergoing surgery. Following on from this audit we have designed a protocol for a prospective randomized trial comparing printed leaflets with web-based patient information.

DECLARATIONS

Competing interests

None declared

Funding

None

Ethical approval

Not applicable

Guarantor

SH

Contributorship

Both authors contributed equally

Acknowledgements

None

Reviewer

Arthur Jones

References

- 1.Department of Health. HSC 2001/023: Good practice in consent: achieving the NHS Plan commitment to patient-centred consent practice. London: Department of Health, 2001. See http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Lettersandcirculars/Healthservicecirculars/DH_4003736 .

- 2.Audit Commission What seems to be the matter: Communication between Hospital and Patients. London: HMSO, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 3.George CF, Waters WE, Nicholas JA Prescription information leaflets: a pilot study in general practice. BMJ 1983;28:1193–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bunker TD An information leaflet for surgical patients. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1983;65:242–3 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]