Abstract

This article describes the results of the WPA-WHO Global Survey of 4,887 psychiatrists in 44 countries regarding their use of diagnostic classification systems in clinical practice, and the desirable characteristics of a classification of mental disorders. The WHO will use these results to improve the clinical utility of the ICD classification of mental disorders through the current ICD-10 revision process. Participants indicated that the most important purposes of a classification are to facilitate communication among clinicians and to inform treatment and management. They overwhelmingly preferred a simpler system with 100 or fewer categories, and over two-thirds preferred flexible guidance to a strict criteria-based approach. Opinions were divided about how to incorporate severity and functional status, while most respondents were receptive to a system that incorporates a dimensional component. Significant minorities of psychiatrists in Latin America and Asia reported problems with the cross-cultural applicability of existing classifications. Overall, ratings of ease of use and goodness of fit for specific ICD-10 categories were fairly high, but several categories were described as having poor utility in clinical practice. This represents an important focus for the ICD revision, as does ensuring that the ICD-11 classification of mental disorders is acceptable to psychiatrists throughout the world.

Keywords: Mental disorders, classification, International Classification of Diseases (ICD), Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), clinical utility, cross-cultural applicability

The World Health Organization (WHO) is in the process of revising the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, currently in its tenth version (ICD-10) 1. The WHO Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse has technical responsibility for the development of the classification of mental and behavioural disorders for ICD-11, and has appointed an International Advisory Group to advise it throughout this process. The WPA is a key partner for WHO in developing the new classification, and as such is officially represented on the Advisory Group.

The conceptual framework that has been articulated by the Advisory Group for the development of ICD-11 mental and behavioral disorders is described in another article in this issue of World Psychiatry 2. That article highlights the improvement of the classification’s clinical utility as a key goal of the current revision process, an issue that has been discussed in more detail elsewhere 3. The WHO has also emphasized the revision’s international and multilingual nature, along with the intention to engage in a serious examination of the cross-cultural applicability of categories, definitions, and diagnostic descriptions.

If improving global clinical utility and cross-cultural applicability represent important goals of the revision, then it is clearly important to obtain information from professionals who come into daily contact with people who require treatment for mental and behavioural disorders in the various countries. Because of the relative scarcity of psychiatrists in many parts of the world, psychiatrists cannot accomplish WHO’s public health goals of reducing the global disease burden of mental and behavioural disorders without the collaboration of other groups. Nonetheless, psychiatrists represent a critical professional group in the diagnosis and management of mental disorders, whose role is essential in all regions of the world.

International surveys represent one of the most feasible methods for obtaining relevant information from professionals. Several studies have used surveys to assess the views of psychiatrists and other mental health professionals regarding the classification of mental disorders. However, previous surveys have been relatively limited in scope, geographically specific, and sometimes characterized by sampling methods that make conclusions difficult. A previous WPA survey including psychiatrists from 66 different countries 4 reported that psychiatrists’ top recommendations for future diagnostic systems concerned broader availability of diagnostic manuals, more effective promotion of diagnostic training, and a wider use of multiaxial diagnosis. However, the reported conclusions were based on only 205 completed questionnaires. In addition, the sample’s representativeness was restricted by only including psychiatrists who were part of the WPA Classification Section, presidents and secretaries of WPA Member Societies, officers of other WPA Sections and “pertinent” network members.

Mellsop et al 5,6 used more widely targeted surveys to assess the use and perceived utility of diagnostic systems among psychiatrists in New Zealand, Japan, and Brazil. The techniques for implementing the surveys varied across countries, partly due to an effort to encourage local ownership of the survey and its results. Based on this work, a similar survey was implemented in Japan, Korea, China and Taiwan 7. Across regions, psychiatrists indicated that they wanted simple, reliable and user-friendly diagnostic tools, although there were significant regional differences in psychiatrists’ views of the cross-cultural applicability of existing classifications, including both the ICD-10 and the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) 8.

Zielasek et al 9 conducted a survey of German-speaking psychiatrists in Germany, Austria and Switzerland regarding their perceptions of mental disorders classification and needs for revision. They investigated the extent to which the ICD-10 adequately reflected actual clinical practice, including its understandability and ease of use. The majority of respondents reported that they were satisfied with the mental disorders chapter of the ICD-10. However, the response rate was low, making it difficult to generalize the results of the survey.

The purpose of the WPA-WHO Global Survey was to expand on the international scope and content of prior surveys to generate information about psychiatrists’ views and attitudes about the classification of mental disorders that would be of direct relevance to the WHO Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse in the revision of the ICD-10. In line with the priorities identified above, the survey was specifically intended for a broad spectrum of practicing psychiatrists, rather than organized psychiatry leadership or individuals with a specific interest in classification. In order to reach this population, the WPA and the WHO partnered with 46 WPA Member Societies (national psychiatric societies) in 44 countries, in all regions of the globe. Through this collaboration, the survey was administered in 19 languages, in order to maximize the participation of international psychiatrists.

The survey focused on major practical and conceptual issues in mental disorders classification as encountered in the day-to-day psychiatric practice, as well as the characteristics of a classification system that international psychiatrists would find most useful. These included the most important purpose of a classification system, the number of categories that should be included for maximum clinical utility, whether the classification should also be useable by other mental health professionals and understandable to relevant non-professionals, what sort of classification system should be used by primary care professionals, whether a system with strict or specified criteria for all disorders or more flexible guidance would be most useful, the best way to conceptualize severity and the relationship between diagnosis and functional status, whether psychiatrists believed that a dimensional component would be a useful addition, and the cross-cultural applicability of existing classifications systems and the perceived need for national classifications. Participating psychiatrists who used the ICD-10 in their day-to-day clinical work were also asked to indicate which specific categories they used frequently, and to provide ratings of the ease of use and goodness of fit of those specific categories.

Participating psychiatrists were contacted via their national psychiatric societies, and told that the purpose of the survey was to provide input to the WHO related to the revision of the ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders. Although it was expected that the survey would also produce information that would be relevant to the ongoing revision of the DSM-IV, unlike some previous surveys 4,10, comparing and contrasting the ICD-10 and the DSM-IV was not a major purpose of the study.

We decided that the most efficient way to implement the survey would be electronically via the Internet, although preserving the option to use a paper-and-pencil methodology for those Societies whose members could not participate in an Internet-based study. At the outset, there was some concern that conducting the survey over the Internet would limit the ability of psychiatrists from low-resource countries to participate. Some previous surveys 5,7 have been conducted via the Internet, but this has tended to be in high-income countries. However, access to the Internet in developing countries has dramatically expanded in recent years, especially among the types of professionals who were the target participants in this survey. If this type of international, multilingual study could be effectively conducted electronically, particularly among low- and middle-income countries, this would have major implications for expanding access and participation in other field studies as a part of the development of ICD-11.

METHODS

In late 2009, the WPA and the WHO (Maj and Saxena) wrote jointly to the Presidents of all WPA Member Societies inquiring about their interest in participating in various aspects of the revision process for the ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders. One of the participation options presented was to participate in a global survey of psychiatrists’ experiences and attitudes regarding the ICD-10 and other mental disorders classifications. Societies were asked to indicate whether they were interested in participating, had the capacity to implement the survey systematically, whether their members could participate in an English-language survey and, if not, whether the Society could translate the survey into the language used by most of its members. Fifty-two Societies responded that they were interested in participating in such a survey.

The survey was developed by Reed, Maj, and Saxena, with input from G. Mellsop (Waikato Hospital, New Zealand) and W. Gaebel and J. Zielasek (University of Düsseldorf, Germany), from whose prior surveys 5,6,9 some questions in the current survey were adapted. Questions on goodness of fit were adapted from the field trial 11 of the Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines for ICD-10 Mental and Behavioural Disorders 12. Feedback on the survey was also provided by the WPA Executive Committee (see Acknowledgements).

Following development of the survey in English, the WHO undertook translation of the survey into French and Spanish, using experts from multiple countries (see Acknowledgements) and an explicit translation methodology that included forward and back translation. The WPA Member Societies which had indicated that they wished to translate the survey into their local languages were provided with a set of translation materials and a translation methodology that included instructions on semantic and conceptual equivalence, forward translation, back translation, and resolution of differences among translators. WPA Member Societies produced item-by-item translations according to these instructions in 16 additional languages (see ).

The survey was prepared for administration in all languages via the Internet using the Qualtrics electronic survey platform (see www.qualtrics.com). The survey was programmed to present only those questions that were relevant to a particular respondent, depending on his or her prior responses. For example, questions related to use of specific ICD-10 categories were skipped for respondents who indicated they do not use the ICD-10 in their clinical practice.

Survey packets were sent to all participating Societies, including instructions for administration, and initial solicitation and reminder messages to send to their members. Messages were provided in English, French and Spanish to the appropriate Societies, and other Societies were asked to translate the solicitation and reminder messages into their local language. Participating WPA Member Societies were informed that the survey data collected from their membership would be jointly owned by the WPA, the WHO and the Society, that they would be provided with the survey results from their own membership, and that they would be free to publish the survey results from their own membership after publication of the international data by the WPA and the WHO.

Those WPA Member Societies that according to WPA records had more than 1,000 members were asked to randomly select 500 eligible members to solicit for participation. Member Societies that had fewer than 1,000 members were asked to solicit all eligible members. Eligible members were defined as all psychiatrist members of the Society who had completed their training.

Participating WPA Member Societies were asked to send a standard initial solicitation message by e-mail or regular mail to the selected sample, and reminder messages to the entire selected sample at 2 weeks and 6 weeks following the initial solicitation. After the second reminder message had been sent, participating Societies were asked to return a Participation Tracking Form, indicating the number of members in the Society, the number of members solicited, the number of solicitations sent by e-mail and by regular mail, the number of solicitation messages returned as undeliverable, and the dates that the initial and reminder solicitations were sent.

The initial solicitation and reminder messages contained a link (Internet address) to the online survey that was unique to each participating Member Society. When the respondent clicked on the link (or entered the Internet address in his or her web browser), he or she was directed to a page that explained the purpose of the survey, its anonymous and voluntary nature, the time required, and its exemption by the WHO Research Ethics Review Committee, and provided relevant contact information in the event of questions or comments. In order to proceed to the survey, the respondent had to affirm that he or she was a psychiatrist who had completed his or her training and that he or she wished to participate in the study.

After receiving the survey packets, two Societies – the Cuban Society of Psychiatry and the Pakistan Psychiatric Society – contacted the WPA and indicated that they felt that their members would be unable to participate in an Internet-based survey. A paper-and-pencil version of the survey, with exactly the same content, was provided to these Societies for their use. The solicitation message to accompany the paper-and-pencil survey gave potential respondents the option of participation via the Internet or by completing the paper-and-pencil survey and returning it to their Society by regular mail.

Data are presented here for the 46 WPA Member Soci- eties in 44 countries that implemented the survey. Participation by Member Societies took place over a period of 11 months, due to the time necessary for Societies to complete translations, make other preparations, and implement the survey. The data presented here were collected between 3 May 2010 and 1 April 2011.

RESULTS

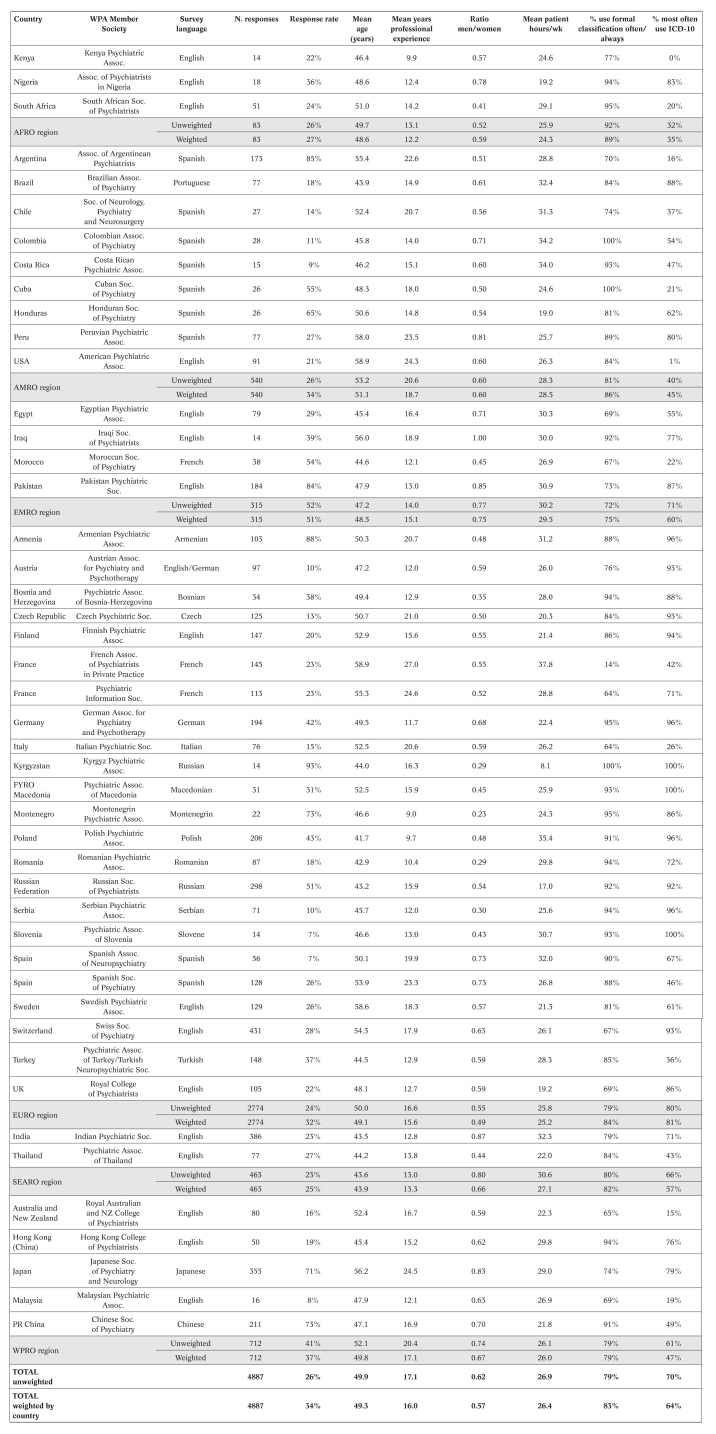

A total of 4,887 psychiatrists worldwide participated in the survey. A list of participating WPA Member Societies, countries, languages of administration, number of participants from each Society, response rate, mean age of respondents, mean number of years of professional experience, and ratio of men to women for each is provided in . Responses in are also aggregated according to the six WHO global regions – AFRO (primarily sub-Saharan Africa), AMRO (the Americas), EMRO (Eastern Mediterranean/North Africa), EURO (Europe), SEARO (Southeast Asia), and WPRO (Western Pacific) – and across the global sample. Weighted totals presented in and elsewhere in this article represent averages of totals by country divided by the number of respondents for that country, so that each country is weighted equally, thus controlling for differences in sample size among countries. A comparison of the unweighted and weighted statistics provides an indication of whether Societies with large samples contributed disproportionately to the overall result.

Response rates

Response rates for each WPA Member Society participating in the Internet-based survey were calculated by dividing the total number of psychiatrists from that Society who accessed the survey website and agreed to participate by the total number of participants solicited by that Society less any returned e-mail or regular mail solicitations. For the paper-and-pencil surveys in Cuba and Pakistan, the response rate represents the number of surveys completed and returned divided by the total sent less any returned as undeliverable. Response rates for each participating Society and aggregated response rates by region and overall are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Table 1 Participating WPA Member Societies, response rates, demographic characteristics, and classification use

As shown in Table 1, the weighted overall global response rate was 34%. However, response rate varied dramatically by Society, from 7% (Slovenian Psychiatric Association, Spanish Neuropsychiatric Association) to 93% (Kyrgyzstan Psychiatric Association). By WHO region, weighted response rates were lowest for SEARO (25%) and highest for EMRO (51%). To examine the impact of country income level on participation in the Internet-based survey, based on the possibility that lower-resource countries would be less technologically able to participate, weighted response rates were calculated for countries grouped by World Bank country income level 13. The mean weighted response rate was 58% for low-income countries, 48% for lower-middle income countries, 30% for upper middle-income countries, and 24% for high-income countries.

Response time

Because the survey was administered electronically, it was possible to capture the amount of time required for each participant to complete it. For the global sample, the mean response time was 21.8 min (weighted mean 21.8 min). Response times of less than 5 min were excluded from this calculation, as were response times of greater than 2 hours (the survey platform made it possible to leave the survey unfinished and come back at a later time to complete it, so using a maximum of 2 hours likely resulted in an overestimation of response time). The average response time was shortest for Italy (13.5 minutes), and longest for Nigeria (34.8 minutes). Response time would be influenced both by speed of Internet connectivity and by the pattern of participants’ responses. For example, respondents who reported that they did not use a formal classification system were not asked subsequent questions about use of specific diagnostic categories.

Amount of patient contact

Globally, 96.7% of the participating psychiatrists reported that they currently saw patients (97.0% weighted by country). Subsequent questions regarding day-to-day clinical work were not presented in the electronic survey to psychiatrists who did not see patients. Of those who reported that they did see patients, 13.8% reported that they saw patients for between 1 and 9 hours during a typical week, 22.3% for between 10 and 19 hours, 44.9% for between 20 and 40 hours, and 18.8% for more than 40 hours. In order to facilitate comparisons across Societies and regions, categorical responses to this question were transformed into a continuous variable by setting “between 1 and 9 hours” to 5, “between 10 and 19 hours” to 15, “between 20 and 40” to 30 and “more than 40 hours” to 50. Table 1 shows the resulting transformed mean number of patient hours per week by Society, by WHO region, and for the global sample.

Regular use of a formal classification system

All participants who reported they saw patients were asked: “As part of your day-to-day clinical work, how much of the time do you use a formal classification system for mental disorders, such as the ICD, the DSM, or a national classification?”. Overall, use of classification systems among psychiatrists participating in the survey was high, with 79.2% of psychiatrists in the global sample who see patients (83.3% weighted) reporting that they “often” or “almost always/always” use a formal classification system as part of their day-to-day clinical work. An additional 14.1% (11.7% weighted) indicated that they “sometimes” use a formal classification system as part of their day-to-day clinical work. The proportion of participants for each Society who reported using a formal classification system “often” or “almost always/always”, as opposed to those who only “sometimes”, “rarely” or “never” did so, is shown in Table 1, as are unweighted and weighted aggregated results by WHO region and globally.

Classification system most used

Participants who saw patients were asked: “In your day-to-day clinical work, which classification system for mental disorders do you use most?” Overall, 70.1% of the global sample (63.9% weighted) reported that ICD-10 is the classification system they use most in their daily clinical work. Most of the remaining participants (23.0% unweighted, 29.9% weighted) reported that the system they use most frequently is the DSM-IV, but 5.6% (5.2% weighted) reported using another classification system, such as the Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders, the Cuban Glossary of Psychiatry, or the French Classification of Child and Adolescent Mental Disorders, and 1.3% (1.0% weighted) reported that they use the ICD-9 or the ICD-8. Table 1 shows the percentage of participating psychiatrists from each WPA Member Society who reported that the ICD-10 is the classification system they use most in daily clinical work, as well as aggregated totals by region and for the global sample.

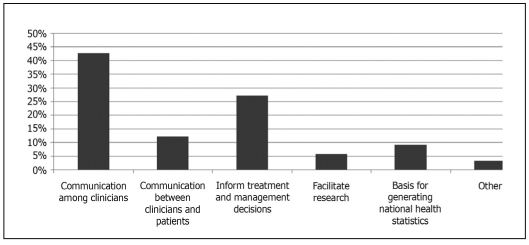

Most important purpose of classification

All participating psychiatrists, including those who do not see patients, were asked: “From your perspective, which is the single, most important purpose of a diagnostic classificatory system?”. Overall global responses are shown in Figure 1. The most important purpose of a diagnostic classification system, from the respondents’ perspective, is communication among clinicians, followed by informing treatment and management decisions.

Figure 1 Percentage of participating psychiatrists endorsing six response options for the single, most important purpose of a diagnostic classificatory system of mental disorders.

Number of categories desired

All participants were asked: “In clinical settings, how many diagnostic categories should a classificatory system contain to be most useful for mental health professionals?”. The overwhelming majority favored a system with dramatically fewer categories than current classification systems: 40.4% responded that a classification system with between 10 and 30 categories would be most useful (39.5% weighted), 47.1% preferred a classification system with 31 to 100 categories (46.9% weighted), 9.2% a classification system with 101-200 categories (9.6% weighted), and only 3.3% a system with more than 200 categories (4.0% weighted). Both the ICD-10 and the DSM-IV contain more than 200 categories.

Use of the classification system by non-psychiatrists

Overall, 79.5% of respondents (79.6% weighted) said that they completely or mostly agreed with the statement “A diagnostic classification system should serve as a useful reference not only for psychiatrists but also for other mental health professionals (e.g., psychologists, social workers, psychiatric nurses)”, and 15.5% (15.6% weighted) said they agreed somewhat. Similarly, 60.4% (61.6% weighted) completely or mostly agreed that “a diagnostic classification system should be understandable to service users, patient advocates, administrators, and other relevant people as well as to health professionals”, and 28.2% (27.3% weighted) agreed somewhat.

Approximately two-thirds of respondents (66.1% unweighted, 64.8% weighted) said that primary care practitioners should have a modified/simpler classification system of mental disorders, while approximately one-third (33.9% unweighted, 35.2% weighted) felt that primary care practitioners should use the same classification system as specialist mental health professionals.

Strict criteria vs. flexible guidance

Only a minority of participants (30.7% unweighted, 31.1% weighted) indicated that for maximum utility in clinical settings a diagnostic manual should contain clear and strict (specified) criteria for all disorders. The large majority (69.3% unweighted, 68.9% weighted) said they would prefer diagnostic guidance that is flexible enough to allow for cultural variation and clinical judgment. This is one of the main differences between the approach taken by the ICD-10 Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines 12 and that of the DSM-IV, so it was relevant to compare the responses of ICD-10 users and DSM-IV users to this question. A slightly higher proportion of global DSM-IV users (72.3%) compared to ICD-10 users (68.3%) expressed a preference for flexible guidance rather than strict criteria (p<0.05).

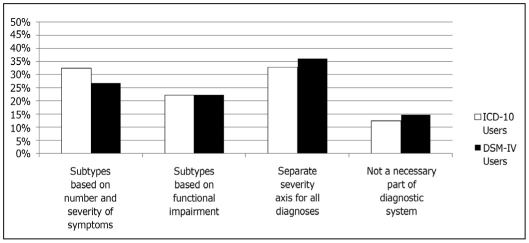

Severity

All participating psychiatrists were asked their view of the best way for a diagnostic system to address the concept of severity. On this issue there was no majority opinion. Because this is an important issue for both the ICD-10 and the DSM-IV revisions 14, results for respondents who most frequently use the ICD-10 as compared to those who most frequently use the DSM-IV are presented in Figure 2. The responses of these two groups were significantly different from one another (p<0.01), with DSM-IV users more likely than ICD-10 users to favor a separate axis allowing an overall assessment of severity that could be used for all diagnoses, and less likely to say that a classification should provide subtypes of relevant diagnostic categories (e.g., mild, moderate or severe depressive episode) based on the number and/or severity of symptoms present.

Figure 2 Percentage of global ICD-10 and DSM-IV users endorsing four options for the best way to address severity in mental disorders classification systems.

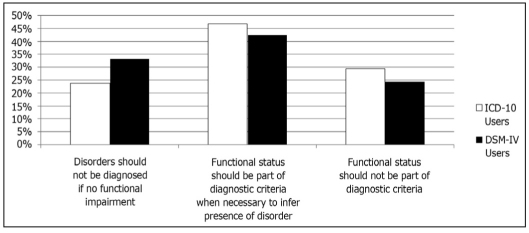

Functional status

Participants were asked: “What is the best way for a diagnostic system to conceptualize the relationship between diagnosis and functional status (e.g., impairment in self-care or occupational functioning)?”. Again, because of the relevance of this issue for both the ICD-10 and DSM-IV revisions 15, responses to this question for ICD-10 users as compared to DSM-IV users are shown in Figure 3. Responses of ICD-10 and DSM-IV users were significantly different from one another (p<0.0001). Although the most frequent response for both groups was that “functional status should be a diagnostic criterion for some mental disorders, when it is necessary to infer the presence of a disorder from its functional consequences”, ICD-10 users more frequently endorsed this option. ICD-10 users were also more likely to say that “functional status should not be included in diagnostic criteria” at all, whereas DSM-IV users were more likely to say that “functional impairment should be a diagnostic criterion for most mental disorders; if there is no functional impairment, then a disorder should not be diagnosed”. This result parallels the difference in the way that issues of functional status and clinical significance are currently treated in the two systems.

Figure 3 Percentage of global ICD-10 and DSM-IV users endorsing three options for diagnostic classification systems to conceptualize the relationship between diagnosis and functional status.

A dimensional component

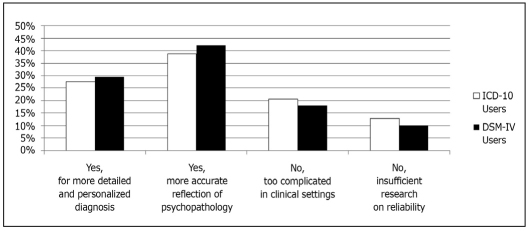

Participants were asked to indicate whether they felt that a diagnostic system should incorporate a dimensional component, where some disorders are rated on a scale rather than just as present or absent. Responses for ICD-10 and DSM-IV users are shown in Figure 4. Although responses of these two groups are significantly different (p<0.05), the patterns are the same. The majority of both groups were favorable to the inclusion of a dimensional component, either because it would make the diagnostic system more detailed and personalized or because it would be a more accurate reflection of the underlying psychopathology. Only a minority said that a dimensional system would be too complicated for use in most clinical systems or that there was insufficient evidence regarding the reliability of such an approach.

Figure 4 Percentage of global ICD-10 and DSM-IV users endorsing four options for whether a diagnostic classification system should incorporate a dimensional component.

Depression and adverse life events

Participants were asked to indicate whether they thought that a diagnosis of depression should be assigned when the depressive symptoms are a proportionate response to an adverse life event (e.g., loss of job or home, divorce). Nearly two-thirds (64.1% unweighted, 64.3% weighted) said yes, that if the full depressive syndrome is present, the diagnosis should be made regardless of whether there are life events that can potentially explain it, with the remaining respondents indicating that a proportionate response to an adverse life event should not be considered a mental disorder.

Cultural applicability and need for a national classification

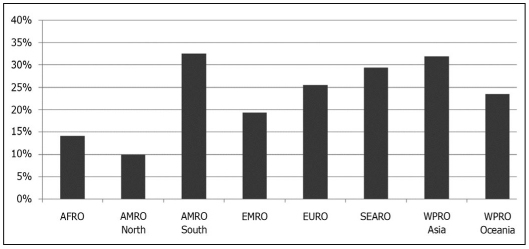

Participants who see patients were asked to rate their level of agreement with the statement “The diagnostic system I use is difficult to apply across cultures, or when the patient/service user is of a different cultural or ethnic background from my own”. Nearly three-quarters of respondents (74.8% unweighted, 71.3% weighted) said that they at least somewhat agreed with this statement. The proportion of psychiatrists by WHO region who mostly or completely agreed with the statement is show in Figure 5. For this analysis, the USA (AMRO North) was separated from Latin America (AMRO South), and Australia and New Zealand (WPRO Oceania) were separated from Asia (WPRO Asia). As shown in Figure 5, there was significant regional variation in agreement with this statement, with over 30% of participating psychiatrists in Latin America and Asia, and nearly 30% of those in Southeast Asia indicating that they mostly or completely agreed, in contrast to only 10% of psychiatrists in the USA.

Figure 5 Percentage of psychiatrists by global region indicating they mostly or completely agreed with the statement “The diagnostic system I use is difficult to apply across cultures, or when the patient/service user is of a different cultural or ethnic background from my own”.

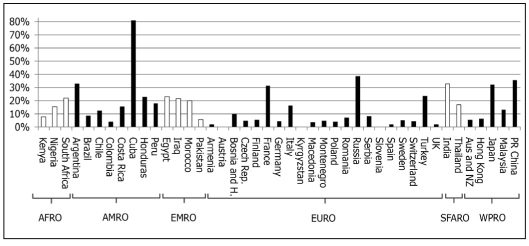

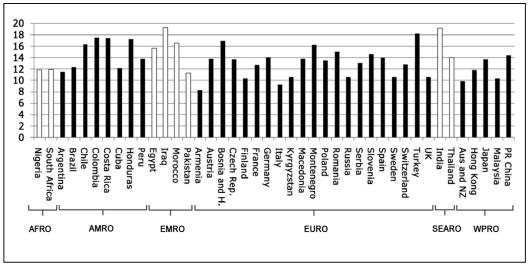

A related question asked of all participants was whether they saw the need for a national classification of mental disorders (i.e., a country-specific classification that is not just a translation of ICD-10). Participants in the USA were not asked this question. Figure 6 shows the percentage of psychiatrists, by country and within WHO region, indicating that they saw such a need in their countries. For presentations of country-level data, data from the two participating Societies in France were combined, as were data from the two participating Societies in Spain. Data for Hong Kong and the People’s Republic of China are presented separately, because of historically different training and practice traditions that may have direct implications for attitudes toward classification. The overwhelming majority of participating Cuban psychiatrists had indicated that the diagnostic system they use most frequently is the Third Cuban Glossary of Psychiatry 16, a Cuban adaptation of the ICD-10 Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines, and these same Cuban participants also endorsed the need for such a national classification, as shown in Figure 6. In addition, more than 30% of psychiatrists in the Russian Federation, the People’s Republic of China, Argentina, India, Japan and France also indicated they saw a need for a national classification of mental disorders.

Figure 6 Percentage of psychiatrists by country and within WHO region, indicating that they saw the need in their countries for a national classification of mental disorders.

Use of ICD-10 diagnostic categories

Participating psychiatrists who indicated they see patients and that the ICD-10 is the diagnostic classification system they use most in day-to-day clinical practice were asked to select from a list of 44 ICD-10 diagnostic categories the ones that they used at least once a week in their day-to-day clinical practice. The list of diagnostic categories presented is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Table 2 List of ICD-10 diagnostic categories from which survey participants were asked to indicate those they used at least once a week

| F00 | Dementia in Alzheimer`s disease | F40.2 | Specific (isolated) phobias |

| F01 | Vascular dementia | F41.0 | Panic disorder |

| F05 | Delirium, not induced by alcohol and other psychoactive substances | F41.1 | Generalized anxiety disorder |

| F10 | Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of alcohol | F41.2 | Mixed anxiety and depressive disorder |

| F11 | Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of opioids | F42 | Obsessive-compulsive disorder |

| F12 | Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of cannabinoids | F43.1 | Post-traumatic stress disorder |

| F13 | Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of sedatives or hypnotics | F43.2 | Adjustment disorder |

| F14 | Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of cocaine | F44 | Dissociative [conversion] disorders |

| F15 | Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of other stimulants | F45 | Somatoform disorders |

| F16 | Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of hallucinogens | F50.0 | Anorexia nervosa |

| F18 | Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of volatile solvents | F50.2 | Bulimia nervosa |

| F20 | Schizophrenia | F51 | Nonorganic sleep disorder |

| F21 | Schizotypal disorder | F52 | Sexual dysfunction |

| F22 | Persistent delusional disorder | F60.2 | Dissocial personality disorder |

| F23 | Acute and transient psychotic disorder | F60.31 | Emotionally unstable personality disorder, borderline type |

| F25 | Schizoaffective disorder | F63 | Habit and impulse disorders |

| F30 | Manic episode | F7 | Mental retardation (i.e., intellectual disability) |

| F31 | Bipolar affective disorder | F84.0 | Childhood autism |

| F32 | Depressive episode | F84.5 | Asperger’s syndrome |

| F33 | Recurrent depressive disorder | F90 | Hyperkinetic disorder |

| F40.0 | Agoraphobia | F91 | Conduct disorder |

| F40.1 | Social phobia | F95 | Tic disorders |

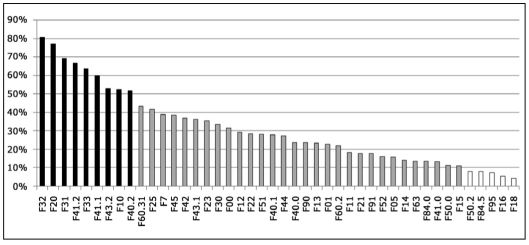

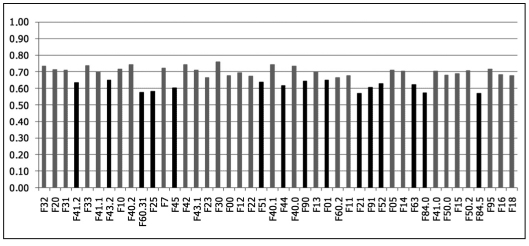

Figure 7 shows the weighted frequency with which participating psychiatrists who were presented with this question selected each diagnostic category, ordered by frequency of use from left to right. Nine categories were selected by more than 50% of participating psychiatrists to indicate that they used them at least once a week: F32 Depressive episode, F20 Schizophrenia, F31 Bipolar affective disorder, F41.2 Mixed anxiety and depressive disorder, F33 Recurrent depressive disorder, F41.1 Generalized anxiety disorder, F43.2 Adjustment disorder, F10 Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of alcohol, and F40.2 Specific (isolated) phobias. Five categories (F18 Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of volatile solvents, F16 Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of hallucinogens, F95 Tic disorders, F84.5 Asperger’s syndrome, and F50.2 Bulimia nervosa) were selected by less than 10% of participating psychiatrists. The average number of categories selected per participant, for each country and within WHO region, is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 7 Percentage of participating psychiatrists indicating that they used each of 44 ICD-10 diagnostic categories at least once a week in their day-to-day clinical practice, weighted by country.

Figure 8 Average number of diagnostic categories used at least once per week, by country and within WHO region.

Ease of use and goodness of fit of ICD-10 diagnostic categories

For each ICD-10 category that a participant had indicated that he or she uses at least once a week, he or she was asked to make two ratings related to the use of that category in clinical practice: a) ease of use; and b) goodness of fit or accuracy of the ICD-10 definition, clinical description and diagnostic guidelines in describing patients he or she sees in clinical practice. Ratings were made on a 4-point scale from 0 (“not at all easy to use in clinical practice” or “not at all accurate”) to 3 (“extremely easy to use” or “extremely accurate”).

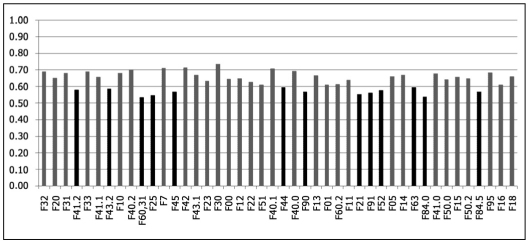

Ratings for ease of use and goodness of fit were strongly, though not perfectly, correlated (overall r = .72, per item range = .65-89). In order to facilitate comparisons, the discrete variables for category ratings were transformed into continuous variables ranging from 0 to 1. Figures 9 and 10 show the mean transformed numerical rating for each category based on participants’ categorical evaluations of their ease of use and goodness of fit, weighted by country, presented in the same order of frequency of use (from left to right) as in Figure 7. A transformed rating of .66 corresponds to a participant rating of 2 (“Quite easy to use” or “Quite accurate”) on ease of use and goodness of fit, and a transformed rating of .33 corresponds to a participant rating of 1 (“Somewhat easy to use” or “Somewhat accurate”). Overall weighted mean ratings for ease of use and goodness of fit were fairly high (.68 for ease of use and .64 for goodness of fit). However, there was substantial variation across categories. Those categories with the lowest ratings of ease of use or goodness of fit – operationalized as those categories for which average ratings of ease of use or goodness of fit were more than 0.5 standard deviations below the overall mean across categories – are shown in Table 3.

Figure 9 Mean transformed “ease of use” ratings for ICD-10 categories, weighted by country, presented in order of frequency of use from left to right.

Figure 10 Mean transformed “goodness of fit” ratings for ICD-10 categories, weighted by country, presented in order of frequency of use from left to right.

Table 3.

Table 3 ICD-10 diagnostic categories rated by participating psychiatrists as having low ease of use or goodness of fit in day-to-day clinical practice relative to other categories

| F01 | Vascular dementia |

| F21 | Schizotypal disorder |

| F25 | Schizoaffective disorder |

| F41.2 | Mixed anxiety and depressive disorder |

| F43.2 | Adjustment disorder |

| F44 | Dissociative [conversion] disorders |

| F45 | Somatoform disorders |

| F51 | Nonorganic sleep disorder |

| F52 | Sexual dysfunction |

| F60.31 | Emotionally unstable personality disorder, borderline type |

| F63 | Habit and impulse disorders |

| F84.0 | Childhood autism |

| F84.5 | Asperger’s syndrome |

| F90 | Hyperkinetic disorder |

| F91 | Conduct disorder |

DISCUSSION

The WPA-WHO Global Survey is the largest and most broadly international survey ever conducted of psychiatrists’ attitudes toward mental disorders classification. Based on the proportion of time spent by participating psychiatrists in seeing patients, the survey was successful in reaching practicing psychiatrists, rather than confining input to the WPA Member Society leadership or to putative classification experts. This study demonstrates that the current ubiquity of electronic communications makes it feasible to implement projects of this nature via the Internet in all but a few parts of the world, suggesting that this mechanism can be used to facilitate a far more distributed and participatory process for the current ICD revision than was possible with previous versions.

The fact that average response rates were actually higher for low- and middle-income countries than for high-income countries parallels the comments of individual members from those countries that they were pleased to be asked for their opinion and enthusiastic about participating. The particular effort made in this collaborative study to implement the survey in 19 languages obviously contributed to making participation as accessible as possible. Even within the European region, there was strong participation from relatively lower-resource countries that are not as commonly involved in Anglophone international projects as their higher-resource neighbors.

The results of the survey demonstrate that formal classification systems of mental disorders are an integrated part of psychiatric practice worldwide. The study was not set up to compare and contrast the ICD and the DSM, given that it was framed as an effort to assist the WHO with the revision of the ICD-10 and would therefore likely have been of more interest to ICD-10 users. However, this global survey of nearly five thousand psychiatrists provides convincing evidence that the ICD-10 is widely used throughout the world, in contrast to older surveys of small and highly selected samples 10.

Through this survey, global psychiatrists provided strong endorsement of a focus on clinical utility during the current ICD-10 revision process. The findings of this survey are consistent with and extend those of Mellsop et al 5,6 and Suzuki et al 7, particularly in terms of the main purpose of classification, the desired number of categories, and the need for a simpler and more clinically useful system. Psychiatrists responding to the current survey indicated that facilitating communication among clinicians and informing treatment and management were the most important purposes of the classification, with research and statistical applications a far lower priority. They indicated that they would prefer a dramatically simplified classification, with 87.5% (86.4% weighted) saying that a classification system of 100 categories or fewer would be most useful.

Results of the survey appear to reflect the multidisciplinary orientation and complex organizational realities of current psychiatric practice. A huge majority of global psychiatrists saw the need for the diagnostic system to be useful for non-psychiatrist mental health professionals, and nearly as many agreed that the system should be understandable to relevant non-professionals. Most also favored the development of a simplified diagnostic system of mental disorders for use in primary care.

Over two-thirds of global psychiatrists indicated that they prefer a system of flexible guidance that would allow for cultural variation and clinical judgment as opposed to a system of strict criteria, and this was true of global users of both the ICD-10 and the DSM-IV. Opinions were divided about how best to incorporate concepts of severity and functional status, suggesting that these areas would be an important focus of further testing, while most respondents were receptive to a system that incorporated a dimensional component in the description of mental disorders. In spite of the recent controversies about the medicalization of normal suffering 17, most global psychiatrists felt that a diagnosis of depression should be assigned even in the presence of potentially explanatory life events.

Although the large majority of psychiatrists worldwide appeared to endorse the possibility of a global, cross-culturally applicable classification system of mental disorders, results of this survey point to several areas of caution. A significant minority of psychiatrists in Latin America and Asia reported problems with the cross-cultural applicability of existing classifications. Substantial proportions of participating psychiatrists in several countries – e.g., Cuba, Russian Federation, People’s Republic of China, Argentina, India, Japan, France – said they see the need for a national classification of mental disorders for use in their countries. This pattern of responses is consistent with previous surveys, reporting variable views across countries of the cross-cultural utility of current classification systems 5. It will be important for the ICD revision process to attend carefully to these perspectives in order to develop a system that is accepted on a global level.

Results of the survey on the use of specific diagnostic categories are interesting in several respects. The list of most commonly used diagnoses overlaps partially, but not entirely, with the most commonly used diagnostic categories found in an international study primarily focused on hospital-based care in 10 countries 18, likely reflecting the use of a somewhat different set of categories in outpatient practice. It is noteworthy that some categories that have generated controversy during the current revision discussions, including F41.2 Mixed anxiety and depressive disorder and F43.2 Adjustment disorder, were very commonly used by psychiatrists worldwide. The extremely widespread use of both F32 Depressive episode and F33 Recurrent depressive disorder is also of interest, as this is one area of difference between the ICD-10 and the DSM-IV. Psychiatrists reported using a relatively small number of categories at least once a week (see Figure 8), ranging from an average of fewer than 10 categories in Armenia and Italy to an average of just under 20 categories in India and Iraq. This appears to be consistent with a general narrowing or constriction of psychiatric practice 19. Future analyses will explore differences in the use of specific diagnostic categories by region and by country.

The information on ease of use and goodness of fit is obviously of direct relevance to the ICD revision, as it points directly to categories where there are perceived to be problems in the definition and diagnostic guidance provided. From a public health perspective, this has particularly important implications for very commonly used categories. It is important to underscore that all ease of use and goodness of fit ratings were made by psychiatrists who reported using the ICD-10 in their daily clinical practice and who indicated that they use that particular category at least once a week. This method was chosen specifically so that ease of use and goodness of fit ratings for each category would be made by those psychiatrists who were most familiar with using them.

Overall, average ease of use and goodness of fit ratings were reasonably high, indicating that psychiatrists who used these categories regularly generally found them easy to use and relatively accurate in describing the patients they saw in clinical practice. These results are consistent with findings from field trials of the ICD-10 Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines 11, which used a similar rating scale for goodness of fit, and those of a recent study of psychiatrists in German-speaking countries 9. However, the results also point to problems with a number of specific categories (see Figures 9 and 10, and Table 3), which should be a focus of attention as a part of the ICD revision process.

The current survey provides both a baseline and a set of specific targets for improvement related to the definition and description of specific mental disorder categories, as well as more general guidance on a series of important issues. The results of this survey will be extremely useful to the WHO in improving the clinical utility of the classification and its global acceptability as a part of the current ICD-10 revision. This study also provides an important example of an extremely rich and successful collaboration among the WHO, the WPA, and WPA Member Societies, and we plan to build on this experience during the next stages of developing the ICD-11.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to G. Mellsop, W. Gaebel and J. Zielasek for their permission to use survey items from their studies. They are also grateful for the suggestions of the WPA Executive Committee, including T. Akiyama, H. Herrman, M. Jorge, L. Kuey, T. Okasha, P. Ruiz and A. Tasman, in developing the survey. They thank S. Evans for his verification of the data. The Spanish translation of the survey was done by P. Esparza with assistance from L. Flórez Alarcón (Colombia), J. Bejarano, G. Amador Muñoz (Costa Rica), M. Piazza (Peru). J.-J. Sánchez-Sosa (Mexico), L. Caris (Chile), and B. Mellor (Spain). The French translation was done by L. Bechard-Evans (Canada), with assistance from A. Lovell, C. Barral, A. Dumas, N. Henckes, B. Moutaud, A. Troisoeufs, P. Roussel (France), and B. Khoury and L. Akoury Dirani (Lebanon). The survey was run on the Qualtrics survey platform provided by the University of Kansas, and the authors are grateful to M. Roberts for his assistance in this matter. They also thank L. Bechard-Evans for setting up the initial version of the survey on the Qualtrics platform and developing the initial translation protocol. Most especially, the authors thank the participating WPA Member Societies for their collaboration in implementing the survey among their memberships, including translation of the questionnaire into the local languages. The German translation prepared by the German Association for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy was also used by the Austrian Association for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy. The Russian translation prepared by the Russian Psychiatric Association was also used by the Kyrgyz Psychiatric Association. Unless specifically stated, the views expressed in this article represent those of the authors and not the official policies or positions of the World Health Organization.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. International classification of diseases and related health problems, 10th revision. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 2.International Advisory Group for the Revision of ICD-10 Mental and Behavioural Disorders. A conceptual framework for the revision of the ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders. World Psychiatry. 2011;10:86–92. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00022.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reed GM. Towards ICD-11: improving the clinical utility of WHO’s international classification of mental disorders. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2010;41:457–464. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mezzich JE. International surveys on the use of ICD-10 and related diagnostic systems. Psychopathology. 2002;35:72–75. doi: 10.1159/000065122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mellsop G, Banzato C, Shinfuku N. An international study of the views of psychiatrists on present and preferred characteristics of classifications of psychiatric disorders. Int J Ment Health. 2008;36:18–26. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mellsop G, Dutu GM, Robinson G. New Zealand psychiatrists views on global features of ICD-10 and DSM-IV. Aust NZ J Psychiatry. 2007;41:157–165. doi: 10.1080/00048670601109931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suzuki Y, Takahashi T, Nagamine M. Comparison of psychiatrists’ view on classification of mental disorders in four East Asian countries/area. Asian J Psychiatry. 2010;3:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed., text revision. Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zielasek J, Freyberger HJ, Jänner M. Assessing the opinions and experiences of German-speaking psychiatrists regarding necessary changes for the 11th revision of the mental disorders chapter of the International Classification of Disorders (ICD-11) Eur Psychiatry. 2010;25:437–442. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maser JD, Kaelber C, Weise R. International use and attitudes toward DSM-III and DSM-III-R: growing consensus in psychiatric classification. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100:271–279. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.3.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sartorius N, Kaelber CT, Cooper JE. Progress toward achieving a common language in psychiatry: results from the field trial of the clinical guidelines accompanying the WHO classification of mental and behavioural disorders in ICD-10. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:115–124. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820140037004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Bank. Country and lending groups. data.worldbank.org.

- 14.Regier DA, Narrow WE, Kuhl EA. The conceptual development of DSM-V. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:645–650. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09020279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Narrow WE, Kuhl EA, Regier DA. DSM-V perspectives on disentangling disability from clinical significance. World Psychiatry. 2009;8:88–89. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2009.tb00222.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Otero-Ojeda A. Third Cuban Glossary of Psychiatry (GC-3): key features and contributions. Psychopathology. 2002;35:181–184. doi: 10.1159/000065142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horwitz AV, Wakefield JC. The loss of sadness: how psychiatry transformed normal sorrow into depressive disorder. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Müssigbrodt H, Michels R, Malchow CP. Use of the ICD-10 classification in psychiatry: an international survey. Psychopathology. 2000;33:94–99. doi: 10.1159/000029127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maj M. Mistakes to avoid in the implementation of community mental health care. World Psychiatry. 2010;9:65–66. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2010.tb00275.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]