Abstract

Background:

QOL (Quality of life) and Disability have been considered inevitable components of schizophrenia from the Biopsychosocial point of view. Studies from over the world have reported significantly lower levels of QOL and higher levels of disability in schizophrenia; but there are equivocal results revealing differences in levels of disability and QOL between genders in schizophrenia.

Aim:

To find out the difference in the levels of QOL and disability in both the genders in schizophrenia remission.

Materials and Methods:

This is cross-sectional study. Sixty patients who gave consent for their participation in the study and satisfying the criterion of remission of schizophrenia, in the age group of 18-60 years, were selected. A purposive sampling technique was used. There were 34 males and 26 females in the study sample. WHO-QOL-BREF ( World Health Organization, Quality of life BREF) and WHO-DAS (World Health Organization–Disability Assessment Schedule) were administered.

Results:

There was a statistically significant difference in the levels of QOL and disability between the genders. Higher scores of WHO-QOL-BREF were seen in the male group, and higher scores of WHO-DAS were seen in the female group.

Conclusion:

Male group had better QOL, and the female group had higher disability.

Keywords: Disability, gender difference, quality of life, schizophrenia in remission

Schizophrenia disorders are characterized, in general, by fundamental and characteristic distortions of thinking and perception, and by inappropriate or blunted affect.[1]

Patients with schizophrenia are considered in remission when they are asymptomatic or have low levels of psychopathology for a minimum period of 6 months. Apart from this, their PANSS (positive and negative symptoms scale) score must be ≤3 on items 1 to 3 of the positive subscale; on items 1, 4 and 6 of the negative subscale; and on items 5 and 9 of the general psychopathology subscale.[2]

Quality of life is a perception of an individual of his position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns. It is a broad-ranging concept affected in a complex way by individuals′ physical health, psychological state, personal beliefs, social relationships and their relationships to the salient features of their environment.[3]

In recent years, the assessment of quality of life (QOL) has become an important indicator in psychiatric research on the functioning and well-being of persons with schizophrenia.[4,5] It is important from the biopsychosocial point of view also.[6] Patients with schizophrenia in remission also show impairment in QOL[7] but lower than that seen in healthy subjects.[8,9] However, there is no difference found with regard to QOL in the domain of environment.[9] Most studies on patients with schizophrenia have shown higher levels of QOL in females.[10,11]

On the other hand, a study by Dirk et al.[12] found no differences in levels of QOL with regard to the gender of schizophrenia patients. Likewise, studies[13–15] by Vandiver[16] found equivocal results with regard to differences in levels of QOL between genders in schizophrenia. He had conducted comparative studies in the United States, Canada and Cuba and reported greater QOL and satisfaction with social relationships among females in Canada; among males, it was higher in the Cuban sample; and no gender differences were found in the United States.

Disability as described by WHO[17] is a complex phenomenon, reflecting an interaction between features of a person's body and features of the society in which he or she lives. Disability also manifests as a result of mental disorders (also known as psychiatric or psychosocial disability).

Anthony[18] suggested that an understanding of psychiatric disability should be derived from the deficits that influence the living, learning and working environments of an individual. Liberman[19] also emphasized that disabilities should be measured and evaluated in a social context.

Ronald, Anton and Hans[20] concluded that disability is associated with schizophrenia, like other psychiatric disorders. Chaves et al.[21] found that males had higher levels of disability than females; but they reported no differences in social role performance between the genders. In contrast, an Indian study by Radha et al.[22] reported that women were more disabled than men, which was because of the prevalent social conditions.

It is possible that various factors such as employment and family support reduce disability due to schizophrenia in developing countries like India.[23]

Thus there are inconsistent results about differences in levels of disability and QOL between genders in schizophrenia, and the differences depend more on social conditions. Therefore, the present study aimed to assess differences in levels of disability and QOL between genders in schizophrenia in Ranchi (Jharkhand).

The significance of the study would be in expanding the assessment of the biopsychosocial aspect. It would help to identify the gender-related issues in schizophrenia and to plan appropriate psychosocial intervention.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and sampling

This is a hospital-based cross-sectional study. The sample comprised of 60 patients diagnosed with schizophrenia. The purposive sampling technique was used. Among these 60 patients, there were 34 males and 26 females. Only patients with schizophrenia in remission were selected. The criterion of remission was as follows.[2]

Those patients who gave consent for their participation in the study and who had not shown any active psychopathology in the last 6 months and scored ≤3 on PANSS (positive and negative symptoms scale)[24] were enrolled for the study. Any patient of schizophrenia who had any organic problem, substance abuse or other co morbidity was excluded from study.

Tools

All patients were screened using PANSS[25] to be judged on the criterion of remission.

The Hindi version of WHO-QOL-BREF (World Health Organization quality of life–BREF) has been developed by Saxena et al.[25] WHO-QOL-BREF consists of four sub domains: (1) physical health, (2) psychological health, (3) social relations and (4) environment.

The Hindi version of WHO-DAS (World Health Organization–disability assessment schedule) has been developed by Behere and Tiwari.[26] WHO-DAS consists of five domains: (1) personal care, (2) social area, (3) occupational, (4) physical and (5) general. Both the tools were used to assess patients.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done using SPSS version 16. Descriptive analysis and chi-square test were used to describe socio-demographic profiles of both the study groups. The t test was used to describe the differences in clinical domains between both the groups.

RESULTS

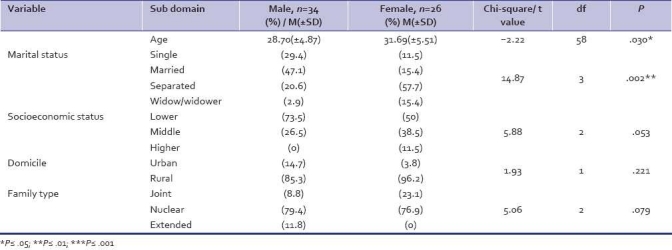

Table 1 describes the socio-demographic profiles of both the groups. The mean age of the male group was 28.70 (±4.87) years; and of female group, 31.69 (±5.51) years; the difference is significant (P= .030). Majority (47.1%) of the males were married; while in the female group, majority (57.7%) of women were separated from their husbands; indicating that there is significant difference in marital status between both the groups (P= .002). Majority in both the groups belonged to nuclear families hailed from rural areas and lower socio Economic strata.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of both the groups

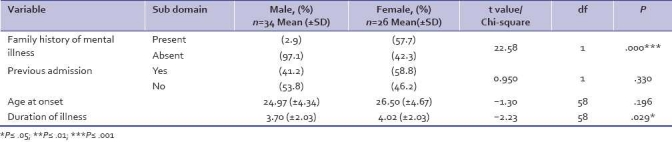

Table 2 reveals that family history of mental illness was more prevalent among female respondents (57.7%) than among male respondents (2.9%); this difference is highly significant (P= .000). Previous admissions were largely reported by females in comparison with males. The mean age of onset in males was 24.97 (±4.34) years; and in females, 26.50 (±4.67) years. The mean duration of illness in males was 3.70 (±2.03) years; and in females, 4.02 (±2.03) years, the difference being statistically significant (P= .029).

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of both the groups

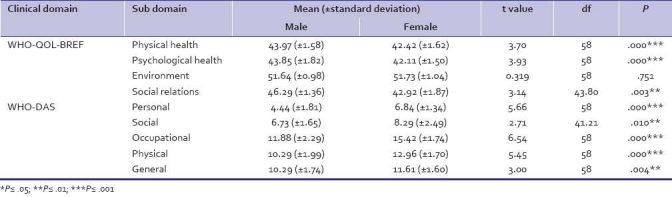

Table 3 showed significant differences in the components of QOL in terms of physical health (P= .000), psychological health (P= .000) and social relations (P= .003). No significant difference was found in the QOL domain of environment; the males showed higher levels of QOL than their female counterparts. In the domains of WHO-DAS, there were significant differences seen between males and females: personal area (P=.000), social area (P= .10), occupation area (P= .000), physical health area (P= .000) and the general area (P= .004). Furthermore, the females showed higher levels of disability than their male counterparts in all the domains of WHO-DAS.

Table 3.

Comparison of quality of life and disability between both the groups

DISCUSSION

The mean age of men in the present study was 28.70 years, which is significantly lesser than the mean age of the women (31.64 years) (P= .030). The duration of illness was found to be significantly longer, viz., 4.02 (±2.03) years, in the female group when compared with that in the male group, viz., 3.70 (±2.03) years (P= .029). The frequency of admission was significantly higher in the female group than in the male group (P= .000), which indicates that females remained more ill than males.

Considering the quality of life, this study shows males had a significantly better quality of life than females with regard to all the domains: physical, psychological (P= .000); and social (P= .003). This result is in contrast to the results found in the studies by Atkinson et al.,[10] Carpiniello et al. and Koivumaa et al.[11] However; there are certain studies[12–15] that did not show any difference in the QOL between genders. The results with regard to the difference between genders in the QOL in schizophrenia have been inconsistent and varying from place to place, as reported by Vandiver[16]; no significant difference was found in the domain of environment; the results in the study by Alptekin et al.[9] were similar to these.

As described by WHO,[3] the concept of QOL is centered on the social and cultural environment of the individual. In this study, a greater number of females were separated from their spouses or were widowed in comparison to their male counterparts, a fact that explains the poorer QOL of females in Jharkhand. In the Indian society, mentally ill patients are prone to be abandoned; especially, females are more susceptible to being separated from their spouses.

The level of disability was found to be significantly higher in the female group than in the male group in all domains of WHO-DAS: personal, occupational, physical (P= .000); social (P= .010); and general (P= .004). This finding is in agreement with that in the study by Radha et al.[22] but in contrast with that in the study by Chaves et al.[21]

With regard to the components of disability, the lower status of occupation can be included, since most of the men were holding jobs, the women primarily were housewives and the young women were dependent on their families for financial support. Rajeev et al.[23] reported that family support and employment can reduce disability. In the present study, the marital status significantly differed between the genders (P= .002); the number of married persons was higher among the males.

The difference in family type was not statistically significant (P= .079); but compared to males, a larger number of females belonged to joint families. The expectation of role performance is higher in a joint family because of a large number of family members; however, on the other hand, there is a possibility of getting more support in a joint family.

The difference in domicile status was also not found to be significant (P= .221); a larger number of males hailed from urban areas in comparison with their female counterparts. Access to various facilities is better in urban areas.

Lastly, it can be concluded that a significant difference in the levels of QOL and disability was found between the genders in this study. Females were found to be more disabled and having poorer QOL than males.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Geneva: WHO; 1993. The International Classification of Diseases-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Diagnostic criteria for research. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andreasen NC, Carpenter WT, Jr, Kane JM, Lasser RA, Marder SR, Weinberger DR. Remission in schizophrenia: Proposed criteria and rationale for consensus. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:441–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Geneva: Division of Mental Health, WHO; 1994. Qualitative research for health Programme. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meltzer HY. Outcome in schizophrenia: Beyond symptom reduction. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woon PS, Chia MY, Chan WY, Sim K. Neurocognitive, clinical and functional correlates of subjective quality of life in Asian outpatients with schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010;34:463–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Awad AG, Hogan TP, Voruganti LN, Heslegrave RJ. Patients’ subjective experiences on antipsychotic medications: Implications for outcome and quality of life. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1995;10:123–32. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199509000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brissos S, Dias VV, Carita AI, Martinez-Arán A. Quality of life in bipolar type I disorder and schizophrenia in remission: Clinical and neurocognitive correlates. Psychiatry Res. 2007;160:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bengtsson-Tops A, Hansson L. Subjective quality of life in schizophrenic patients living in the community: Relationship to clinical and social characteristics. Eur Psychiatry. 1999;14:256–3. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(99)00173-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alptekin K, Akvardar Y, Akdede BB, Dumlu K, Isik D, Pirincci F, Yahssin S, Kitis A. Is quality of life associated with cognitive impairment in schizophrenia? Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29:239–44. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atkinson M, Zibin S, Chuang H. Characterizing quality of life among patients with chronic mental illness: A critical examination of the self-report methodology. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:99–105. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koivumaa-Honkanen HT, Viinamäki H, Honkanen R, Tanskanen A, Antikainen R, Niskanen L, et al. Correlates of life satisfaction among psychiatric patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;94:372–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb09875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heider D, Angermeyer MC, Winkler I, Schomerus G, Bebbington PE, Brugha T, et al. A prospective study of Quality of life in schizophrenia in three European countries. Schizophr Res. 2007;93:194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andrews FM, Withey SB. Social Indicators of well- being. New York: Plenum Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campbell A, Converse PE, Rogers WL. The Quality of American Life. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kearns RA, Taylor SM, Dear M. Coping and satisfaction among the chronically mentally disabled. Can J Commun Ment Health. 1991;6:13–25. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vandiver VL. Quality of life, gender and schizophrenia: A cross-national survey in Canada, Cuba and USA. Community Ment Health J. 1998;34:501–22. doi: 10.1023/a:1018742513643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.WHO. Geneva: WHO; 1980. International classification of Impairment Disability and Handicap. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buell GJ, Sharratt S, Althoff ME. The efficacy of psychiatric rehabilitation. Psychol Bull. 1972;78:447–56. doi: 10.1037/h0033743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liberman RP. Presented at the 140th Meeting A.P.A. Chicago: Illinois; 1987. Psychosocial interventions in the management of schizophrenia, overcoming disability and handicap. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bottlender R, Strauss A, Möller HJ. Social disability in schizophrenic, schizoaffective and affective disorders 15 years after first admission. Schizophr Res. 2010;116:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chaves AC, Seeman MV, Mari JJ, Malief A. Schizophrenia: Impact of positive syptoms on gender social five year follow up findings. Psychol Med. 1993;22:13l–45. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shankar R, Kamath S, Joseph AA. Gender differences in disability: A comparison of married patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 1995;16:17–23. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(94)00064-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krishnadas R, Moore BP, Nayak A, Patel RR. Relationship of cognitive function in patients with schizophrenia in remission to disability: A cross-sectional study in an Indian sample. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2007;6:19–28. doi: 10.1186/1744-859X-6-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–76. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sabena S, Chandiramani K, Bhargava R. WHOQOL-Hindi: A questionnaire for assessing quality of life in health care settings in India: World Health Organization Quality of Life. National Natl Med J India. 1998;11:160–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Behre PB, Tiwari K. Manual for disabilty assessment schedule. Varanasi: Rupa Psychological Center; 1991. [Google Scholar]