Abstract

Cryptophane-A, comprised of two cyclotriguaiacylenes joined by three ethylene linkers, is a prototypal organic host molecule that binds reversibly to neutral small molecules via London forces. Of note are trifunctionalized, water-soluble cryptophane-A derivatives, which exhibit exceptional affinity for xenon in aqueous solution. In this paper, we report high-resolution X-ray structures of cryptophane-A and trifunctionalized derivatives in crown–crown and crown–saddle conformations, as well as in complexes with water, methanol, xenon or chloroform. Cryptophane internal volume varied by more than 20% across this series, which exemplifies 'induced fit' in a model host–guest system.

Cryptophane-A is a prototypical organic host molecule that binds reversibly to neutral guest molecules. Taratula et al. report X-ray structures of cryptophane-A complexed with a range of host molecules to show that the cryptophane host–guest system exhibits ‘induced fit’.

Cryptophane-A is a prototypical organic host molecule that binds reversibly to neutral guest molecules. Taratula et al. report X-ray structures of cryptophane-A complexed with a range of host molecules to show that the cryptophane host–guest system exhibits ‘induced fit’.

Molecular recognition is required for numerous processes in chemistry, biology and engineering. One prominent example is enzyme–substrate (E–S) complex formation, which, as Koshland1 proposed in 1958, may occur by 'induced fit'. Enzyme active sites undergo dynamic recognition upon substrate binding, with E and S rapidly adopting complementary conformations tailored for enzyme catalytic function. Such molecular recognition depends on the size and shape of the enzyme host and substrate guest molecules, as well as on conformational flexibility2,3,4,5. The complexity of non-covalent host–guest interactions in natural supramolecular assemblies motivates our study of smaller synthetic systems.

Cryptophanes are widely investigated synthetic host molecules6 whose internal volume can be varied by changing the length or composition of the three alkane linkers joining two cyclotriguaiacylene (CTG) units. The linkers form three pores, which control guest entry, serving as size- and shape-selective filters. Numerous solution studies have characterized the reversible binding of cryptophane hosts to small molecules6. The internal volume of cryptophane-A with three ethylene linkers was reported previously as either 81.5 Å3 (ref. 7) or 95 Å3 (ref. 8), on the basis of modelling studies. The spherical molecules methane (28 Å3), xenon (42 Å3) and chloroform (72 Å3) gain entry, and span the range of accessible volumes. Methane binds to cryptophane-A with a relatively large association constant compared with other host molecules, KA=130 M−1 at 298 K in C2D2Cl4 (ref. 7). Under these conditions, similar binding to crytophane-A occurs with chloroform, KA=230 M−1 (ref. 7), and by far the highest affinity has been measured for xenon, KA=3,900 M−1 (ref. 9). The preference for xenon has been a mystery: using the available chloroform–cryptophane-A structures10 as a template, the Xe atom is predicted to underfill the cavity.

To date, cryptophanes-A10 and -E11 have only been crystallized with chloroform, and cryptophanes-C and -D have been crystallized with dichloromethane12,13. Cavagnat et al.10 obtained small crystals of the CDCl3–cryptophane-A complex in three different morphologies (rhombic, rod-like and polyhedral) and these were structurally determined by X-ray diffraction and studied by Raman microspectrometry. However, no small-molecule X-ray structure of a xenon–cryptophane complex has been reported. Providing some precedent are crystal structures of xenon bound to calixarene14,15 and cucurbit[5]uril16 hosts. Also relevant are protein X-ray crystal structure determinations in which xenon was used as a heavy atom to improve phasing17. Finally, we reported a 1.7-Å resolution macromolecular crystal structure of a xenon biosensor bound to carbonic anhydrase II, which indicated electron density corresponding to a single xenon atom bound within the cryptophane18.

There is growing interest in functionalized cryptophane-A derivatives based on the significant potential of hyperpolarized 129Xe for biodetection and biomolecular imaging19,20. Recently, MS2 virus capsid decorated with 125 cryptophanes was detected at sub-picomolar concentrations by hyperpolarized 129Xe nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy21. Using a tripropargyl-derivatized cryptophane-A, our laboratory synthesized cryptophane-benzenesulfonamide biosensors that produced 129Xe NMR chemical shift differences of 3.0–7.5 p.p.m. on binding carbonic anhydrase isozymes22. We also generated peptide-modified cryptophane that was delivered to human cancer cell lines23.

A triacetate-functionalized cryptophane-A24 shows the highest xenon affinity of any host molecule, KA=3.3×104 M−1 at 293 K in buffer. The higher affinity of xenon for cryptophane in water results from entropic ('hydrophobic') effects that likely involve desolvation of xenon clathrates upon complexation. We have also hypothesized that cryptophane-A adopts a more compact shape in water, which should increase favourable van der Waals contacts with xenon24. Although conformational flexibility of the three alkoxy linkers has been observed in solution previously9,25,26, until now, there has been little evidence of volume changes in the 'open' crown–crown (CC) conformation of cryptophane-A, and this is often considered as a fixed cavity.

Synthetic host binding sites have also been investigated with macrocyclic compounds such as cyclodextrins, crown ethers and cyclophanes27,28. Cyclodextrin studies suggest that the guest inclusion process is influenced by hydrophobic interactions, as well as by the shape and size of the guest28. Recently, crystallographic studies revealed changes in β-cyclodextrin conformation upon quinine encapsulation29.

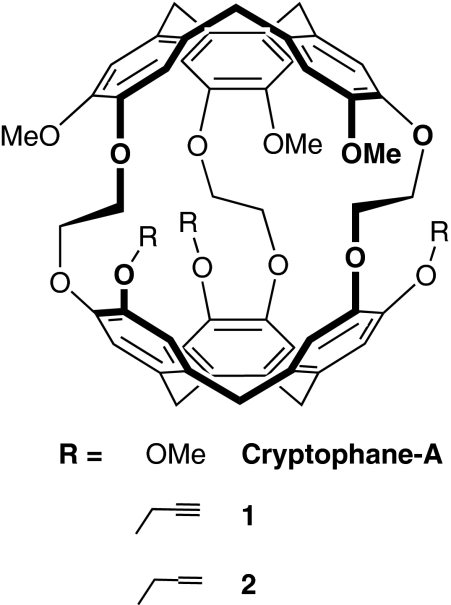

Here, we report X-ray crystal structures showing analogous induced fit in a cryptophane host–guest model system. Unlike many small-molecule host systems that have been characterized crystallographically to date, cryptophanes contain a three-dimensional hydrophobic cavity, which approximates many enzyme active sites. Because of minimal electrostatic interactions in these host–guest complexes, cryptophane binding is driven by favourable London forces. Cryptophane-A, tripropargyl (1) and triallyl (2) derivatives (Fig. 1) were crystallized with various encapsulated hydrophobic guests, including xenon. Notably, the cryptophane internal volume increased by more than 20% as the guest volume increased from methanol to chloroform.

Figure 1. Cryptophane hosts used in this study.

Cryptophane-A, tripropargyl (1) and triallyl (2) derivatives are shown as single enantiomers.

Results

Crystallization parameters

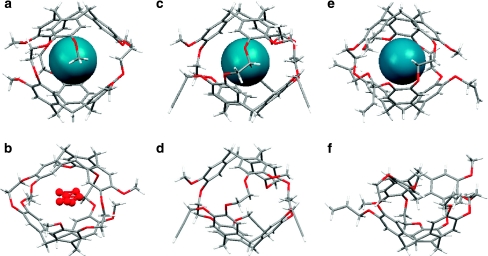

For crystallization of cryptophane–guest complexes, it was necessary to avoid solvents that compete for binding inside the cryptophane cavity. Fluorobenzene is a sterically bulky solvent that adequately solubilizes 1 and 2 to allow for crystal growth by vapour diffusion of diethyl ether or n-pentane. Cryptophane-A, 1 and 2 as racemic mixtures cocrystallized with xenon exhibited the CC conformation (Fig. 2a,c,e). Moreover, in the absence of suitable guests, the crystal structure of 1 revealed cryptophane in the CC conformation (Fig. 2d), in agreement with solution 1H NMR data. Either without guests or with xenon, 1 crystallized in the triclinic space group P1. The chirality of cryptophane-A arises from the anti relationship of the methoxy groups relative to the ethylene oxide bridges, as was also observed in previous cryptophane X-ray structures6,11.

Figure 2. X-ray crystal structures of cryptophanes and inclusion complexes in side view.

(a) Cryptophane-A with Xe, and b, with water, oxygen shaded red; both in CC conformation. (c) Tripropargyl cryptophane (1), with Xe, and d, partially occupied; both in CC conformation. (e) Triallyl cryptophane (2), with Xe, in CC conformation. Xe atom is shaded blue; and f, collapsed, in CS conformation.

Complexed and collapsed cryptophane structures

Crystal structures of cryptophane-A, 1 and 2 with xenon as guest (Fig. 2a,c,e) revealed, as expected, one Xe atom centrally located within the cryptophane cavity. From the calculated Xe-carbon atom distances at the phenyl rings in the Xe-2 complex (range=4.03–4.73 Å, average=4.31 Å, Supplementary Table S1), it is evident that Xe is positioned near the optimal distance from CTG units: van der Waals interaction distance for Xe and phenyl carbon is 3.86 Å30 (where steric repulsion and favourable induced dipolar interaction are balanced).

We also report the first X-ray structure of cryptophane-A cocrystallized with water (Fig. 2b). The cryptophane–water structure was found to encapsulate one water molecule containing partial electron density from the water oxygen atom occupying seven different positions within the cavity. This disordered arrangement is consistent with 'bound' water not being observed at room temperature by solution 1H NMR spectroscopy. It is relevant that molecular dynamics simulations previously identified an average of only ∼2.1 water molecules within the somewhat larger cryptophane-E cavity31.

A crystal structure was obtained for 2 in a 'collapsed' crown–saddle (CS) conformation (Fig. 2f). CS-2 crystallized in the monoclinic space group P21/n with two of the allyl groups observed in two different possible orientations. This experimentally determined structure appears to agree with the one calculated previously by Huber et al.32 The C1 symmetric structure of CS-2 (Fig. 2f) shows the bridging methylene pointing into the cavity. Although CS-2 is the first crystal structure of the CS conformer of a cryptophane-A derivative, a related CS conformer of a cryptophane possessing m-xylyl linkers between the CTG units was previously studied by solution 1H NMR spectroscopy and single crystal X-ray diffraction by Mough et al.33. Although it is expected that CS-2 is destabilized relative to the crown form of CTG by 3–4 kcal mol−1 (ref. 34), we conclude that crystal packing forces on 2 in the absence of guest can promote the CS conformation in the solid state. Interestingly, the allyl-substituted CTG of CS-2 retained its crown conformation, whereas the methoxy-substituted CTG assumed the saddle conformation. The crystal structure of CS-2 suggests that tri-substituted cryptophane-A derivatives can access this energetically less stable, non-xenon-binding conformer in solution as well, as we previously proposed for water-soluble cryptophane-A derivatives24 and as observed for hexa-acid cryptophane-A derivatives32.

Cryptophane host–guest volume calculations

Mecozzi and Rebek surveyed many host–guest interactions mediated by London forces and determined empirically that optimal binding occurs when the guest occupies 55±9% of the host interior volume8. In cryptophane host systems in organic solution and water, it has been established that the lengths and conformations of the alkoxy linkers connecting the two CTG units regulate the size of the internal cavity, which in turn affects the Xe binding constant32,35. For example, a smaller cryptophane-1,1,1 was synthesized36 with an approximate internal volume of 81 Å3, making the volume ratio of the xenon guest to the host cavity equal to ∼0.52. In this case, the xenon association constant, KA=10,000 M−1 at 298 K in (CDCl2)2 (ref. 36), was determined to be almost threefold higher than that for cryptophane-A. Xenon binding may be nearly optimized for the cavity in cryptophane-1,1,1, although, without crystal structures, the Xe packing fraction can only be approximated for this host–guest complex.

To investigate systematically the manner in which the size of the guest molecule influences the cryptophane cavity, we determined structures of the readily crystallized triallyl cryptophane 2 with MeOH, Xe and CDCl3. The internal volumes of 2 in these complexes were calculated with Swiss Pdb Viewer37 after deleting the encapsulated guest from the pdb files (Table 1). Although crystal packing forces undoubtedly have an effect on the observed molecular conformations, the fact that 2–guest complexes all crystallized in the monoclinic space group P21/c facilitates comparisons between the different structures. In contrast, we were unable to find an internal void volume for CS-2, as the collapsed cavity was too small to accommodate a 1.4 Å diameter probe.

Table 1. Internal volumes of host molecule cryptophane-A and derivatives 1 and 2, guest volumes, and packing coefficients.

| Guest | Host | Internal volume (Å3)* | Guest volume (Å3) | Packing coefficient† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 'Collapsed' | CS-2 | — | — | — |

| Partial occupancy | CC-1‡ | 87 | — | — |

| H2O | Crypt-A | 88 | 18 | 0.20§ |

| MeOH | 2 | 84 | 33 | 0.39 |

| Xe | 2 (conf. 1)∥ | 89 | 42 | 0.47 |

| 2 (conf. 2)∥ | 87 | 42 | 0.48 | |

| 1 | 85 | 42 | 0.49 | |

| Crypt-A | 89 | 42 | 0.47 | |

| CDCl3 | 2 (conf. 1)∥ | 102 | 72 | 0.71 |

| |

2 (conf. 2)∥ |

98 |

72 |

0.73 |

*Internal volumes were calculated using Deep View/Swiss Pdb Viewer.

†Packing coefficient is guest volume divided by host internal volume.

‡Diffuse electron density was observed inside the CC-1 cavity, which cannot be assigned to an encapsulated guest but is likely due to trace water.

§This value is based on one bound water molecule, whereas partial electron density corresponding to water in seven different positions was observed.

∥Some crystal structures gave two conformers, which differed slightly in the orientations of the side chains and in their calculated internal volumes.

As can be seen in Table 1, the internal volume of 2 increased by a remarkable 21%, from 84 to 102 Å3 as the size of the guest molecule increased from MeOH to CDCl3. The guest packing coefficient (defined as guest volume divided by host internal volume) increased even more dramatically across this series, 0.39→0.73. Importantly, cryptophane-A, 1 and 2—with different peripheral substituents—exhibited very similar cavity volumes for the same guest. Thus, it was possible to compare crystallographic data for these three cryptophane hosts. Xenon bound to cryptophane-A, 1 and 2 gave similar cavity volumes (85–89 Å3) and packing coefficients (0.47–0.49, Table 1). Cryptophane-A adopts an intermediate-volume conformation for Xe, which brings the packing fraction close to Rebek's empirically determined value. This presumably achieves a favourable balance of enthalpic and entropic forces and contributes to high Xe affinity. Notably, an overlay of the CC-1 and 1-Xe structures showed virtually no change induced by Xe encapsulation (see Supplementary Fig. S1). This provides further evidence that the cryptophane-A structure is nearly optimal for Xe binding.

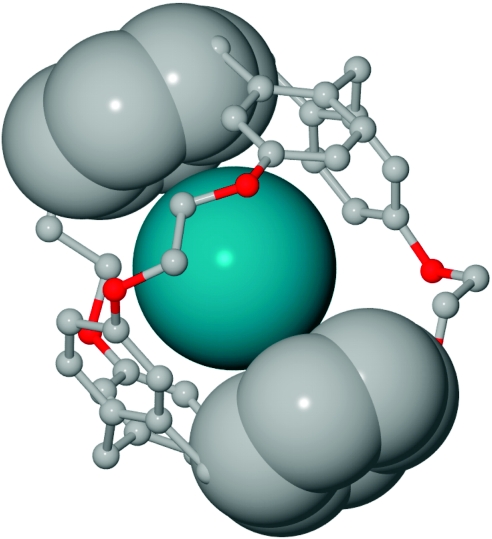

Figure 3 illustrates how xenon is sandwiched by three pairs of phenyl rings belonging to the two opposing CTG units. As noted previously, many of the phenyl carbon atoms nearly achieve van der Waals contact with Xe. In contrast, the Xe-C distances at the linkers are larger (range=4.54–5.41 Å, average=5.00 Å, Supplementary Table S1), when the van der Waals interaction distance for Xe and tetrahedral carbon is 4.16 Å30. The flexible ethylene linkers reside farther away (Fig. 3) and interact more weakly with Xe, on average, but provide the CTG units with mobility to accommodate Xe in the cavity and optimize Xe–phenyl interactions.

Figure 3. Zoomed view of the Xe-2 complex.

This highlights van der Waals interactions between phenyl carbon atoms and xenon. Hydrogen atoms and side chains were removed for clarity. Only Xe atom and two phenyl groups from opposing CTG units are depicted with van der Waals radii.

Unlike xenon, MeOH clearly underfills the cryptophane cavity, with packing coefficient 0.39 (Table 1). Importantly, MeOH is very similar in size to methane, which is the smallest molecule the binding of which has been characterized for cryptophane-A7. On the basis of the low packing coefficient for this smallest guest, it appears to be energetically unfavourable for the cavity to shrink to less than 84 Å3, as found in the MeOH structure. Crystal packing forces may also have a role in stabilizing the conformation of cryptophane in the MeOH structure.

The other exception to Rebek's '55% solution'8 involves CDCl3, which at 72 Å3 has the potential to fill the cryptophane cavity almost entirely. In fact, the cryptophane volume expanded to 102 Å3 in the 2-CDCl3 structure, which reduced the entropic penalty but still yielded a large packing coefficient of 0.73.

Cavagnat et al.10 determined that the chlorine atoms of chloroform occupy the central equatorial plane of cryptophane-A, and the C–H bond is collinear with the C3 axis of the cryptophane molecule. A similar orientation of chlorine atoms was observed for the larger cryptophane-E host, in which the C–H bond points either up or down along the pseudo C3 axis, towards one of the CTG units11. For 2-CDCl3, we observed a similar orientation of the guest, with the deuterium directed to the centre of the allyl-modified CTG (see Supplementary Fig. S2). We reviewed the previously deposited chloroform-bound cryptophane-A structures in the three different crystal morphologies (rhombic, rod-like and polyhedral; CSD ref. codes IYEVEN, IYETUB and IYEVAJ)10, but were unable to reliably calculate the volume of cryptophane-A, or identify meaningful conformational differences between these structures, because of a high degree of molecular disorder. To a coarse approximation, similarly large cavities were identified for the three different structures, with expanded volumes consistent with the 2-CDCl3 structure.

Cryptophane conformational changes seen for induced fit

By overlaying the computed cavities for 2-MeOH and 2-CDCl3, it is evident that CDCl3 binding induces the cavity to expand from the centre of mass (Supplementary Fig. S3). The crystallographic data indicate that the cavity can adapt to fit the encapsulated guest molecule. How does this 'induced fit' occur?

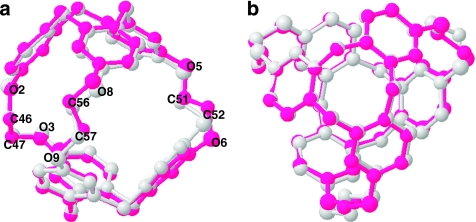

Overlaid structures of 2, complexed with MeOH and CDCl3 (Fig. 4), provide clear indication that the internal volume of cryptophane-A is controlled by the three O-CH2-CH2-O linkers connecting the CTG units. We used CrystMol 2.1 (ref. 38) to superimpose the carbon backbone structures of 2 with bound MeOH and CDCl3, as these guests produced the largest difference in host cavity volume (Table 1). The superimposed cryptophane structures show the smaller 2-MeOH structure (Fig. 4, grey carbon backbone) residing mostly inside the pink carbon backbone representing 2-CDCl3. The structures can be aligned such that one of the ethylenedioxy linkers (labelled O(2)-C(46)H2-C(47)H2-O(3)) is almost unchanged. However, linker O(8)-C(56)H2-C(57)H2-O(9) in the 2-CDCl3 complex is partly expanded such that the O(8)-O(8) and C(56)-C(56) distances between the two structures differ by 0.56 and 0.65 Å, respectively. An even more pronounced change is seen for the third linker, (O(5)-C(51)H2-C(52)H2-O(6)); O(6)-O(6) and C(52)-C(52) distances differ by 0.89 and 1.06 Å (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table S2). These data show that cryptophane-A can expand both horizontally and vertically upon binding the larger chloroform guest, moving the CTG units farther apart by as much as 0.4 Å.

Figure 4. Side (a) and (b) top views of two superimposed crystal structures of triallyl cryptophane (2).

2 is shown encapsulating MeOH (grey) and CDCl3 (pink). Guests, hydrogens and side chains were removed for easier viewing.

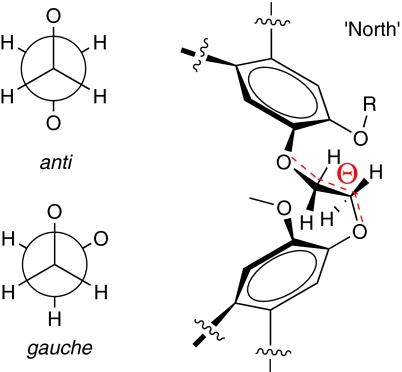

In this crystallographic study, we also examined geometrical parameters of the ethylenedioxy linkers that changed during the guest-binding process. In contrast with previous solution spectroscopic studies9,25,26, ethylenedioxy linkers exhibited mixed anti and gauche conformations in the solid state. This determination was based on measured dihedral angles (Θ1, Θ2, Θ3) for all three linkers from the perspective of the 'north' pole of the cryptophane, as defined by CTG with allyl substituents (Fig. 5). By increasing the guest volume from MeOH to CDCl3, the most dramatic change was observed for the linker labelled O(5)-C(51)H2-C(52)H2-O(6): the conformation changed from gauche to anti with the dihedral angle decreasing from 74.5° to −171.7° (Table 2). Such linker transformations allow the increased vertical distance between CTG units observed for chloroform encapsulation (Supplementary Table S2), and also allow the cavity to expand horizontally upon binding this largest guest. The superimposition of cryptophane structures with different sized guests, in addition to calculated internal volumes and dihedral angles, indicate how cryptophane-A can accommodate guests of varied shape and size.

Figure 5. Ethylenedioxy linker of cryptophane-A.

Both anti and gauche conformations are observed in all crystal structures of cryptophane host–guest complexes.

Table 2. Crystallographically determined dihedral angles and conformational assignments of the -O-CH2-CH2-O- linkers in 1 and 2.

| Guest | Host | Θ 1(°)*/Conf. | Θ 2(°)*/Conf. | Θ 3(°)*/Conf. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 'Collapsed' | CS-2 | 63.9/gauche | −87.7/gauche | −63.9/gauche |

| Partial occupancy | CC-1 | 72.3/gauche | −165.3/anti | 73.8/gauche |

| MeOH | 2 | 77.4/gauche | 171.9/anti | 74.5/gauche |

| Xe | 2 (conf. 1)* | 73.4/gauche | −167.2/anti | −175.8/anti |

| 2 (conf. 2)* | 73.5/gauche | −166.9/anti | 70.7/gauche | |

| 1 | 71.9/gauche | −164.8/anti | 73.2/gauche | |

| CDCl3 | 2 (conf. 1)* | 75.3/gauche | −174.0/anti | −171.7/anti |

| |

2 (conf. 2)* |

75.0/gauche |

75.4/gauche |

−174.0/anti |

*Measured dihedral angles: Θ 1: O2-C46-C47-O3; Θ 2: O8-C56-C57-O9; Θ 3: O5-C51-C52-O6.

Discussion

Previously unstudied in the solid state, xenon–cryptophane association was shown earlier in solution studies to depend on many factors, including the size, shape, rigidity, accessibility and polarity of the cage, as well as solvent. In particular, the Xe–cryptophane-A binding interaction has been studied by several experimental techniques including isothermal titration calorimetry, electronic circular dichroism, vibrational circular dichroism (VCD), NMR, as well as infrared and fluorescence spectroscopies9,25,35,39,40,41,42. 129Xe NMR chemical shift varies considerably in different cryptophane environments and solvents19,20, but requires further benchmarking before it can be used to illuminate Xe–cryptophane interactions. Spin polarization-induced nuclear Overhauser effect measurements can estimate xenon–proton internuclear distances for cryptophane in solution, on the basis of site-selective 1H NMR enhancements from hyperpolarized 129Xe (ref. 40); however, crystal structures should allow more accurate distance assignments.

Interestingly, the packing fraction of 0.73 determined for the 2-CDCl3 structure is consistent with the closest packing arrangement of uniform spheres, in which the fraction of space occupied by the spheres is 0.74. A packing fraction of 0.73 suggests a nearly maximal internal volume for the cryptophane, particularly as no guest larger than chloroform has been reported to be encapsulated by cryptophane-A in solution. The expanded (102 Å3) cavity volume observed for 2-CDCl3 stands in contrast to the 82 Å3 volume reported for the previous cryptophane-A–chloroform crystal structures10, although this value appears to be approximated. The calculation of crystallographically determined molecular cavity volumes and the observed expansion of the cryptophane cage upon binding larger guests are useful for addressing important issues first raised by Collet and co-workers7 about the atomic densities and pressures that can be achieved in non-covalent cryptophane–guest complexes.

Previous solution studies showed that encapsulation of guests by cryptophane-A can induce conformational changes in ethylenedioxy linkers9,25,26,43. For example, chiroptical changes observed by VCD and electronic circular dichroism indicated that cryptophane-A ethylenedioxy linkers adopt an all-anti conformation upon encapsulation of bulky guests such as chloroform25. Moreover, experimental and simulated VCD spectra suggested a preferential gauche linker conformation when cryptophane-A is without any guests or bound to smaller guests26. 1H NMR spectroscopy also indicated that OCH2CH2O linkers adopt a gauche conformation in the Xe–cryptophane-A complex9. Contrary to these solution studies, we observed a mixture of both gauche and anti linker conformations in all cryptophane crystal structures, except for the all-gauche CS-2 collapsed structure. In the CC cryptophane structures, the linker conformations were not correlated with the presence of guests or guest volume.

This crystallographic study improves understanding of the prototypal cryptophane host and related cavity-containing organic host molecules, which are often assumed to adopt conformations with a narrow range of cavity volumes. This is also relevant for xenon biosensing applications, as manipulating the cryptophane cavity can produce significant changes in xenon affinity and 129Xe NMR chemical shift. Finally, London forces are important to all molecular interactions in Nature, but are often difficult to elucidate because of their small magnitude (typically <2 kJ mol−1) and the predominance of electrostatic interactions. The study of model host–guest systems using X-ray crystallography is useful for elucidating the role of weak interactions in molecular recognition.

In conclusion, we report the first crystal structures of cryptophane-A and derivatives without guests in CC and CS conformations, as well as in complexes with chloroform, xenon, methanol and water. A crystallographic analysis revealed that these cryptophanes can undergo 'induced fit' to improve guest binding interactions; the internal volume of the host varied by more than 20% to accommodate a wide range of hydrophobic guests. The ethylenedioxy linkers of cryptophane-A confer conformational flexibility that allows both vertical and lateral changes to the cavity, for adaptation to guests ranging in volume from MeOH (33 Å3) to CDCl3 (72 Å3). Of particular interest are xenon-bound structures, which identify nearly optimized van der Waals interactions between xenon and the CTG phenyl moieties.

Methods

Synthesis

Cryptophane-A was obtained by seven-step synthesis with an overall yield of 4.4% (ref. 44). Tripropargyl (1) and triallyl (2) cryptophane derivatives were synthesized according to published procedures in 9 and 10 steps with an overall yield of 4.9 and 2.9%, respectively24,45.

Crystal growth

Cryptophane-A and compounds 1 and 2 were each crystallized as a racemic mixture, with guests (H2O, MeOH, Xe, CDCl3) or without guests, by slow evaporation or by vapour diffusion of diethyl ether, n-pentane or hexanes into different solvents. Single crystals were grown in CDCl3 by slow evaporation, whereas crystals of MeOH included within the cryptophane cavity were grown by vapour diffusion. Fluorobenzene was chosen as solvent to grow cryptophane-xenon crystals as it is too large to occupy the cavity of the cryptophane and exhibits enough solubility towards cryptophanes to allow for the growth of a single crystal by vapour diffusion technique. The fluorobenzene solution of cryptophane was degassed with static vacuum and bubbled with Xe gas. The precipitating solvent (diethyl ether, n-pentane or hexanes) was also bubbled with Xe and the headspace of the vapour diffusion vial was purged with Xe before it was sealed. Single crystals of 'collapsed' CS-2 were obtained by means of dissolution in hot mesitylene, cooling to room temperature and subjecting to vapour diffusion conditions with n-pentane.

Crystal structure determination

X-ray intensity data were collected on a Rigaku AFC7 four-circle diffractometer equipped with a Mercury CCD area detector using graphite-monochromated Mo-Ka radiation (λ=0.71073 Å) at T=143 K. All structures were refined to convergence against F2 using programs from the SHELX family46. Selected parameters are summarized in the Supplementary Tables S3–S5 and full details are given in Supplementary Data 1–8.

The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center (http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/conts/retrieving.html) hosts the crystallographic data for these compounds. Deposition numbers: CCDC-778896 (cryptophane-A with H2O); CCDC-778897 (cryptophane-A with Xe); CCDC-778902 (tripropargyl cryptophane 1, partially occupied); CCDC-778903 (tripropargyl cryptophane 1 with Xe); CCDC-778898 (triallyl cryptophane 2, collapsed); CCDC-778899 (triallyl cryptophane 2 with CDCl3); CCDC-778900 (triallyl cryptophane 2 with MeOH); and CCDC-778901 (triallyl cryptophane 2 with Xe). ORTEP representations of eight reported structures are presented as Supplementary Figure S4a–h.

Author contributions

O.T. wrote the manuscript, optimized many of the synthetic protocols, synthesized tripropargyl cryptophane and crystallized two of the reported cryptophane complexes. P.A.H. synthesized triallyl cryptophane, cryptophane-A and grew crystals that led to most of the reported cryptophane structures. N.S.K. helped to synthesize cryptophane precursors; P.J.C. performed X-ray crystal structure determinations and provided support with structural analysis; I.J.D. supervised this project and edited the manuscript.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Taratula, O. et al. Crystallographic observation of 'induced fit' in a cryptophane host–guest model system. Nat. Commun. 1:148 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1151 (2010).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures S1-S4 and Supplementary Tables S1-S5

Crystallographic data for cryptophane-A-H2O

Crystallographic data for cryptophane-A-Xe

Crystallographic data for collapsed tri-allyl cryptophane 2

Crystallographic data for tri-allyl cryptophane 2-CDCl3

Crystallographic data for tri-allyl cryptophane 2-MeOH

Crystallographic data for tri-allyl cryptophane 2-Xe

Crystallographic data for partially occupied tripropargyl cryptophane 1

Crystallographic data for tri-propargyl cryptophane 1-Xe

Acknowledgments

Support came from DOD (W81XWH-04-1-0657), NIH (CA110104, CA110104), NSF (CHE-0840438), a Camille and Henry Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar Award, and from the UPenn Chemistry Department.

References

- Koshland D. E. Application of a theory of enzyme specificity to protein synthesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 44, 98–104 (1958). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutman A. B. C. et al. Squaring cooperative binding circles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 10471–10476 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluth M. D., Fiedler D., Mugridge J. S., Bergman R. G. & Raymond K. N. Encapsulation and characterization of proton-bound amine homodimers in a water-soluble, self-assembled supramolecular host. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 10438–10443 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feringa B. L. From molecules to molecular systems. Chimia 63, 254–256 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Kim B. S. et al. Water soluble cucurbit[6]uril derivative as a potential Xe carrier for Xe-129 NMR-based biosensors. Chem. Commun. 2756–2758 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotin T. & Dutasta J. P. Cryptophanes and their complexes-present and future. Chem. Rev. 109, 88–130 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garel L., Dutasta J. P. & Collet A. Complexation of methane and chlorofluorocarbons by cryptophane-A in organic solution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 32, 1169–1171 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Mecozzi S. & Rebek J. The 55% solution: a formula for molecular recognition in the liquid state. Chem. Eur. J. 4, 1016–1022 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Bartik K., Luhmer M., Dutasta J. P., Collet A. & Reisse J. Xe-129 and H-1 NMR study of the reversible trapping of xenon by cryptophane-A in organic solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 784–791 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Cavagnat D. et al. Raman microspectrometry as a new approach to the investigation of molecular recognition in solids: chloroform-cryptophane complexes. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 5572–5581 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Canceill J. et al. Structure and properties of the cryptophane-E CHCl3 complex, a stable van der Waals molecule. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 28, 1246–1248 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- Canceill J., Cesario M., Collet A., Guilhem J. & Pascard C. A new bis-cyclotribenzyl cavitand capable of selective inclusion of neutral molecules in solution—crystal-structure of its CH2Cl2 cavitate. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 361–363 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- Canceill J. et al. Selective recognition of neutral molecules: 1H NMR study of the complexation of CH2Cl2 and CH2Br2 by cryptophane-D in solution and crystal structure of its CH2Cl2 cavitate. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 339–341 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer E. B., Enright G. D. & Ripmeester J. A. Solid state NMR and diffraction studies of p-tert-butylcalix[4]arene*nitrobenzene*xenon. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 119, 939–940 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Enright G. D., Udachin K. A., Moudrakovski I. L. & Ripmeester J. A. Thermally programmable gas storage and release in single crystals of an organic van der Waals host. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 9896–9897 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyahara Y., Abe K. & Inazu T. 'Molecular' molecular sieves: lid-free decamethylcucurbit[5]uril absorbs and desorbs gases selectively. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 41, 3020–3023 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiltz M., Fourme R. & Prange T. Use of noble gases xenon and krypton as heavy atoms in protein structure determination. Methods Enzymol. 374, 83–119 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aaron J. A. et al. Structure of a 129Xe-cryptophane biosensor complexed with human carbonic anhydrase II. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 6942–6943 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthault P., Huber G. & Desvaux H. Biosensing using laser-polarized xenon NMR/MRI. Progr. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 55, 35–60 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Taratula O. & Dmochowski I. J. Functionalized Xe-129 contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 14, 97–104 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meldrum T. et al. A xenon-based molecular sensor assembled on an MS2 viral capsid scaffold. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 5936–5937 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers J. M. et al. Cryptophane xenon-129 nuclear magnetic resonance biosensors targeting human carbonic anhydrase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 563–569 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seward G. K., Wei Q. & Dmochowski I. J. Peptide-mediated cellular uptake of cryptophane. Bioconjug. Chem. 19, 2129–2135 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill P. A., Wei Q., Troxler T. & Dmochowski I. J. Substituent effects on xenon binding affinity and solution behavior of water-soluble cryptophanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 3069–3077 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchet A., Brotin T., Cavagnat D. & Buffeteau T. Induced chiroptical changes of a water-soluble cryptophane by encapsulation of guest molecules and counterion effects. Chem. Eur. J. 16, 4507–4518 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotin T., Cavagnat D. & Buffeteau T. Conformational changes in cryptophane having C-1-symmetry studied by vibrational circular dichroism. J. Phys. Chem. A 112, 8464–8470 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami Y., Kikuchi J., Hisaeda Y. & Hayashida O. Artificial enzymes. Chem. Rev. 96, 721–758 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rekharsky M. V. & Inoue Y. Complexation thermodynamics of cyclodextrins. Chem. Rev. 98, 1875–1917 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Z. et al. Encapsulation of quinine by beta-cyclodextrin: excellent model for mimicking enzyme-substrate interactions. J. Org. Chem. 71, 1244–1246 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondi A. Van der Waals volumes + radii. J. Phys. Chem. 68, 441–451 (1964). [Google Scholar]

- Kirchhoff P. D. et al. Structural fluctuations of a cryptophane host: a molecular dynamics simulation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 3237–3246 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Huber G. et al. Water soluble cryptophanes showing unprecedented affinity for xenon: candidates as NMR-based biosensors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 6239–6246 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mough S. T., Goeltz J. C. & Holman K. T. Isolation and structure of an 'imploded' cryptophane. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43, 5631–5635 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collet A. Cyclotriveratrylenes and cryptophanes. Tetrahedron 43, 5725–5759 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- Brotin T. & Dutasta J. P. Xe@cryptophane complexes with C-2 symmetry: synthesis and investigations by Xe-129 NMR of the consequences of the size of the host cavity for xenon encapsulation. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 973–984 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Fogarty H. A. et al. A cryptophane core optimized for xenon encapsulation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 10332–10333 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guex N. & Peitsch M. C. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis 18, 2714–2723 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchamp D. J. CrystMol, Version 2.1. (DandA Consulting LLC, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- Huber J. G. et al. NMR study of optically active monosubstituted cryptophanes and their interaction with xenon. J. Phys. Chem. A 108, 9608–9615 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Luhmer M. et al. Study of xenon binding in cryptophane-A using laser-induced NMR polarization enhancement. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121, 3502–3512 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Darzac M., Brotin T., Rousset-Arzel L., Bouchu D. & Dutasta J. P. Synthesis and application of cryptophanol hosts: Xe-129 NMR spectroscopy of a deuterium-labeled (Xe)2@bis-cryptophane complex. New J. Chem. 28, 502–512 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Desvaux H., Huber J. G., Brotin T., Dutasta J. P. & Berthault P. Magnetization transfer from laser-polarized xenon to protons with spin-diffusion quenching. ChemPhysChem 4, 384–387 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotin T., Cavagnat D., Dutasta J. P. & Buffeteau T. Vibrational circular dichroism study of optically pure cryptophane-A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 5533–5540 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill P. A. Synthesis of functionalized cryptophane-A derivatives and assessment of their xenon-binding properties for the construction of hyperpolarized xenon-129 biosensors. University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA (2008).

- Hill P. A., Wei Q., Eckenhoff R. G. & Dmochowski I. J. Thermodynamics of xenon binding to cryptophane in water and human plasma. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 9262–9263 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. M. SHELXL-97. Acta. Cryst. A64, 112–122 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures S1-S4 and Supplementary Tables S1-S5

Crystallographic data for cryptophane-A-H2O

Crystallographic data for cryptophane-A-Xe

Crystallographic data for collapsed tri-allyl cryptophane 2

Crystallographic data for tri-allyl cryptophane 2-CDCl3

Crystallographic data for tri-allyl cryptophane 2-MeOH

Crystallographic data for tri-allyl cryptophane 2-Xe

Crystallographic data for partially occupied tripropargyl cryptophane 1

Crystallographic data for tri-propargyl cryptophane 1-Xe