Abstract

Background

Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT) has been used to treat adults and adolescents with suicidal and non-suicidal self-injury. This article describes initial progress in modifying DBT for affected pre-adolescent children.

Method

Eleven children from regular education classes participated in a 6-week pilot DBT skills training program for children. Self-report measures of children’s emotional and behavioural difficulties, social skills and coping strategies were administered at pre- and post-intervention, and indicated that the children had mild to moderate symptoms of depression, anxiety and suicidal ideation at baseline.

Results

Subjects were able to understand and utilise DBT skills for children and believed that the skills were important and engaging. Parents also regarded skills as important, child friendly, comprehensible and beneficial. At post-treatment, children reported a significant increase in adaptive coping skills and significant decreases in depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation and problematic internalising behaviours.

Conclusions

These promising preliminary results suggest that continued development of DBT for children with more severe clinical impairment is warranted. Progress on adapting child individual DBT and developing a caregiver training component in behavioural modification and validation techniques is discussed.

Keywords: Children, Dialectical Behaviour Therapy, self-harm, self-injury, suicide

Introduction

Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT) is an empirically supported intervention for adults with Borderline Personality Disorder exhibiting suicidality and non-suicidal self-injury (for example, cutting) (Linehan et al., 2006). DBT targets affective and behavioural dysregulation by teaching coping skills and using problem solving within a validating environment. DBT has been adapted for suicidal and self-injurious adolescents (Miller, Rathus, & Linehan, 2007). The efficacy of DBT for adults and adolescents holds promise for adapting DBT for children with suicidality and/or self-injury. In the past 20 years, death rates by suicide for children aged 5 to 14 years of age have doubled. Up to 25% of outpatient and 80% of psychiatric inpatient 6- to 12-year-old children exhibit suicidal behaviours (Pfeffer et al., 1986). Yet there are no established interventions to help these youths.

This article describes progress in adapting DBT for pre-adolescent children, including: 1) adapting DBT skills training to accommodate the developmental level of younger children and testing the ability of children to understand the adapted skills; and 2) plans for adapting individual DBT and developing a caregiver training component in behavioural modification and validation techniques.

Adapting DBT skills training for children

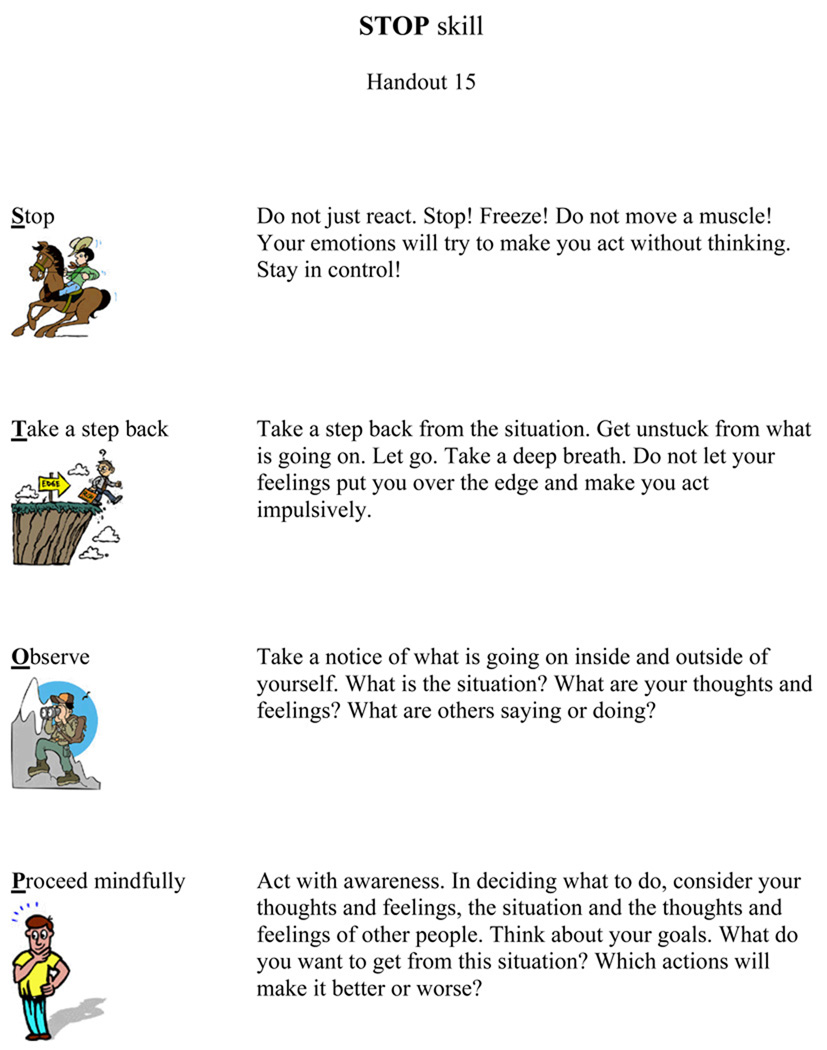

The adaptation of DBT for children necessitates substantial revisions to accommodate their developmental level. However, DBT is a principle-based intervention not defined by specific format, techniques or a set of skills but, rather, by the balance of acceptance and change within a dialectical framework. DBT for children adheres to these principles whilst utilising child-friendly materials and activities designed to engage children, sustain their attention, and motivate skills building. DBT skills, including mindfulness, distress tolerance, emotion regulation and interpersonal effectiveness, were adapted from the adult and adolescent manuals (Linehan, 1993; Miller, Rathus, & Linehan, 2006) via focus-group discussions with DBT clinicians and researchers, and in consultations with experts, including Marsha Linehan and Alec Miller, who expressed great enthusiasm and support for this project. Adapted materials include cartoons, large font sizes, limited amount of text per page, and language geared for a second-grade reading level. Didactic materials have also been simplified and condensed (see Table 1). For example, ‘Wise Mind ACCEPTS’ and ‘IMPROVE the moment’ DBT skills (Linehan, 1993) were combined into one ‘DISTRACT.’ Furthermore, new skills were introduced, including the ‘STOP’ skill, aimed at increasing awareness and decreasing impulsivity (see Figure 1) and the ‘Surfing Your Emotion’ skill that teaches children to regulate emotional arousal.

Table 1.

DBT for children skills training modules

| Mindfulness | |

| Introduction | Mindfulness is paying attention on purpose, in the moment and without judgments. |

| States of Mind | “Emotion Mind,” “Reasonable Mind,” and “Wise Mind.” |

| What skills | Observing and describing behaviors and emotions, and participating in activities with awareness. |

| How skills | Focusing on one thing in a moment, entering into the experience non-judgmentally and doing what works. |

| Distress Tolerance | |

| STOP skills | Avoiding impulsive reactions using the acronym STOP: Stop and do not move a muscle, Take a step back, Observe what is going on, Proceed mindfully. |

| DISTRACT | Controlling emotional and behavioral responses in distress using the acronym DISTRACT: Do something else, Imagine pleasant events, Stop thinking about it, Think about something else, Remind yourself of positive experiences, Ask others for help, Count your breath, and Take a break. |

| Self-Soothing | Tolerating distress by using five senses. |

| Pros and Cons | Considering pros and cons of responding to distress. |

| Letting It Go | Techniques for accepting events that cannot be changed. |

| Willfulness and Willingness | Being willing to accept reality as it is as opposed to being willful in refusing to tolerate distress. |

| Emotion Regulation | |

| The Wave | Emotion Wave is seen as going through 6 stages: event, thought, feeling, action urge, action and after effect. |

| Surfing Your Emotion | Regulating emotional arousal by just attending to an emotion without trying to change its intensity |

| Opposite Action | Changing affective reaction by acting opposite to the emotion. |

| PLEASE skills | Reducing emotional vulnerability with PLEASE skills: attend to PhysicaL health, Eat healthy, Avoid drugs/alcohol, Sleep well, and Exercise |

| LAUGH skills | Increasing positive emotions with LAUGH skills: Let go of worries, Apply yourself, Use coping skills, set Goals, and Have fun. |

| Interpersonal Effectiveness | |

| Worry Thoughts & Cheerleading | Goals of interpersonal effectiveness, what gets in the way of being effective and cheerleading statements. |

| Goals | Two kinds of interpersonal goals, “getting what you want” and “getting along.” |

| DEAR skills | How to “get what you want” using DEAR skills: Describe the situation, Express feelings and thoughts, Ask for what you want, Reward or motivate the person. |

| FRIEND skills | How to “get along” by using the FRIEND skill: be Fair, Respect the other person, act Interested, Easy manner, Negotiate and be Direct. |

Figure 1.

Example of the DBT for Children skills training handout

The presentation of didactic materials is augmented by colourful handouts, experiential exercises, board games, multimedia, in-session practices and role plays.

Experiential exercises allow participants to experience aspects of the presented skills and may require materials (for example, food or clay) or consist of games (see Appendix A for examples). Through trial and error we learned that mindfulness practices must be active to maintain children's engagement and can be used as breaks from periods of sustained attention.

In-session practice is used to enhance understanding and performance of presented techniques. Practices follow presentation of didactic materials and include therapists modelling the skills. During practices, therapists shape the performance by prompting and reinforcing successive approximations of target behaviours.

Role plays give children an opportunity to practise skills in a playful way and apply techniques to real-life situations.

Multimedia presentations utilise video clips with cartoon characters to model the use of skills and engage children in discussion. For instance, a tiger is afraid of water, but has to jump into a river to save his friends who may otherwise drown. This clip exemplifies the emotion-regulation skill ‘opposite action’, or acting opposite to the action urge elicited by an emotion. Our library contains over 100 cartoon clips, with 1 to 7 clips per skill. This allows therapists to select clips based on children's developmental level, favourite characters and time limitations (i.e. clips range from 20 seconds to 4 minutes). Children indicate enhanced understanding of skills following video presentation and discussion, as well as better recollection of skills.

Before testing the adapted DBT skills training with suicidal and/or self-injurious children, we assessed its feasibility with a sample of children drawn from a non-clinical setting. If these children were unable to understand DBT concepts or apply the skills, then research with severely affected children would not be warranted.

Method

Sample

This pilot was conducted with children from regular education classes recruited from a local school. Participation was initiated by sending parents of all children in grades 2 to 6 (a total of 257 children) information packs that included descriptions of the intervention and parent consent forms. All children whose parents replied within one week were included in the pilot and were trained in one group. The sample included 11 children (6 girls and 5 boys), ranging from 8 years and 0 months to 11 years and 6 months (M = 9.83, SD = 1.24); 73% were Caucasian (n = 8), 9% were Black (n = 1), 9% were Hispanic (n = 1) and 9% were Asian (n = 1). A total of 64% (n = 7) of the children had clinically significant symptoms as indicated by published clinical cut-offs on the Mood and Feeling Questionnaire (MFQ; Costello & Angold, 1988) and Self-Report for Childhood Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED; Birmaher et al., 1999), including: 55% (n = 6) for depression, 45% (n = 5) for anxiety, 36% (n = 4) for both depression and anxiety, and 45% (n = 5) for endorsed suicidal ideations.

Measures

Children completed the MFQ, SCARED, Children’s Coping Strategies Checklist (CCSC; Sandler et al., 1990) and the Child Self-Control Rating Scale (CSCRC; Rohrbeck, Azar, & Wagner, 1991). Furthermore, Skills Training and Homework Review Questionnaires, rated on a 4-point scale, were developed for this project to assess children’s interest, understanding and ability to utilise skills (can be obtained from the first author). Children anonymously filled out this questionnaire after each session. Parents completed the Emotion Regulation Checklist (ERC; Shields & Cicchetti, 1997), the Social Skills Ratings Scale-Parent Version (SSRS-P; Gresham & Elliott, 1990) and the Skills Training Attitude Inventory, a 6-item measure developed to assess whether parents found skills important, child-friendly, understandable, enjoyable and useful for their children (can be obtained from the first author). Parents anonymously filled out this questionnaire after the program was completed.

Intervention

Group skills training with children lasted 6 weeks. Children attended sessions twice a week for skills training and homework review. At each skills training session, the children received handouts outlining the presented skills, participated in experiential exercises, and were assigned homework. During homework review children role played their utilisation of skills.

Results

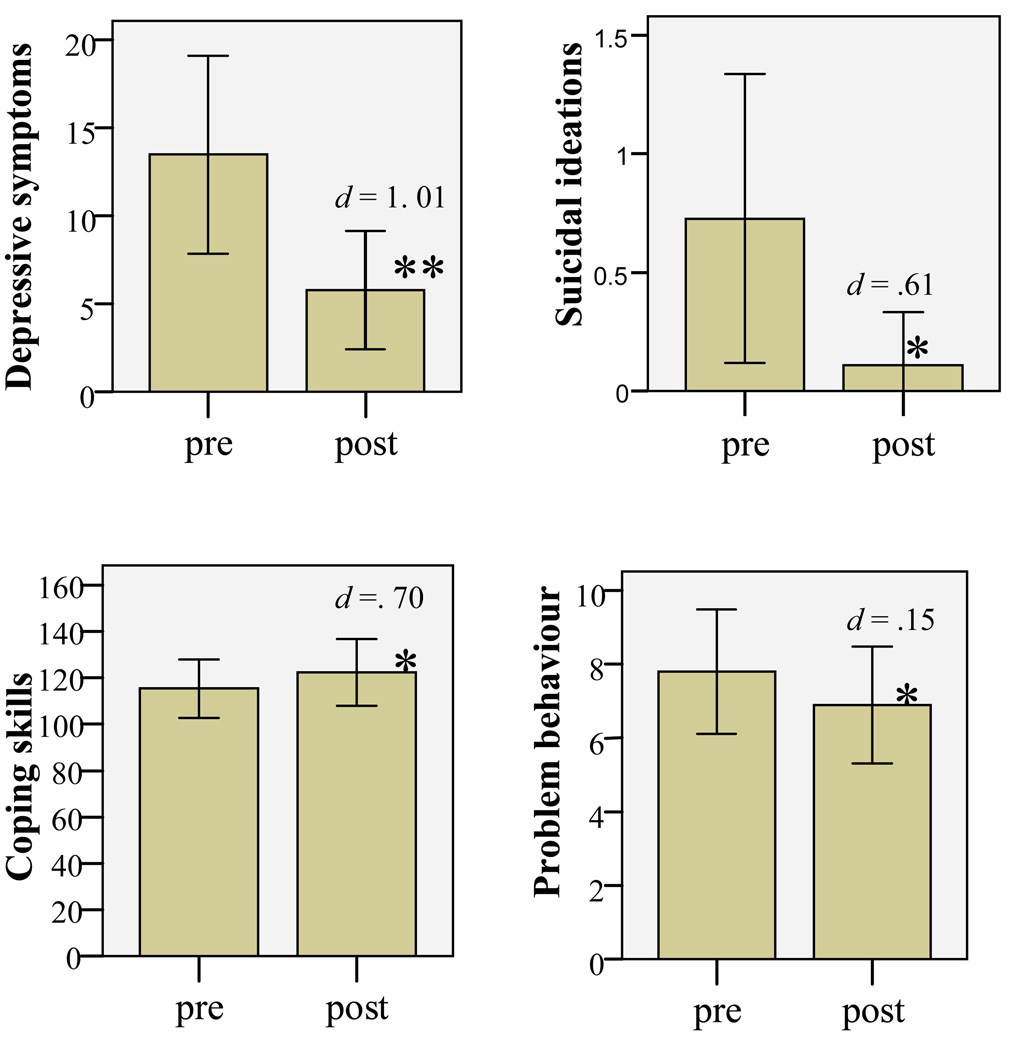

Children and their parents reported moderate to high acceptability of the skills training (see Table 2) and changes in children’s symptoms over time was examined (see Figure 2). Given the small sample size, the directional nature of our hypotheses and the empirical support for adult and adolescent DBT, we used one-tailed paired samples t tests to assess changes in children’s symptoms over time. Results indicated decreased MFQ depressive symptoms from pre- (M = 14.22, SD = 9.78) to post-intervention (M = 5.78, SD = 5.04), t (8) = 3.94, p < .005; Cohen’s d = 1.01, and decreased suicidal ideations from pre- (M = .89, SD = 1.05) to post-intervention (M = .11, SD = .33), t (8) = 2.14, p < .05; Cohen’s d = .61 as measured by MFQ items reflecting suicidality. CCSC adaptive coping skills increased from pre- (M = 108.56, SD = 14.83) to post-intervention (M = 122.33, SD = 21.53), t (8) = 2.01, p < .05; Cohen’s d = .70. SSRS-P Behavioural problems decreased from pre- (M = 7.89, SD = 2.80) to post-intervention (M = 6.89, SD = 2.37), t (8) = 2.27, p < .05; Cohen’s d = .15. With more conservative two-tailed tests, only results for the MFQ depressive symptoms retained significance (< .01), while changes on the other measures indicated a trend (< .08).

Table 2.

Feasibility and acceptability of DBT for Children skills training

| Children reported that they ‘mostly’ or ‘a lot’ | % |

|---|---|

| - Understood presented skills | 87.5 |

| - Thought that they can use presented skills | 78.6 |

| - Found skills important | 80.3 |

| - Found skills fun | 66.0 |

| - Found that practising skills by doing homework was important | 75.0 |

| - Found that reviewing homework helps understand skills better | 67.9 |

| Parent reported that they ‘mostly’ or ‘a lot’ | |

| - Thought that skills were important for their children to learn | 77.8 |

| - Thought that their children were able to understand skills | 88.9 |

| - Thought that their children were able to use skills | 66.7 |

| - Found skills child-friendly | 100 |

| - Thought that their children enjoyed participation in skills programme |

100 |

| - Thought that their children benefited from the programme | 100 |

Figure 2.

Change in outcome measures

Note: * p < .05; ** p < .01; d = Cohen’s d; error bars represent standard error

Discussion

The results of this study indicated initial acceptability, feasibility and efficacy of the adapted DBT skills. Self-reported abilities to understand and utilise DBT skills were supported by therapists’ observations during homework review, as children were able to use skills appropriately. Parental attitudes indicated overall acceptance of the intervention. However, children’s ability to use skills was the only parental rating below ‘mostly’ on average in the attitude inventory. This finding is consistent with the contention that DBT skills training requires parental reinforcement and involvement in skills practice (Miller et al., 2007). We are currently developing a caregiver training component, discussed in the next section. Results of this study should be considered in light of its limitations, including the small non-clinical sample, no control group, and brief duration of the intervention. While there are insufficient data to generalise the results to clinical groups, the primary aims of the study were to establish feasibility and acceptability of materials for this age group, which appear successful from the current findings. This investigation was also limited to adapting DBT skills and does not provide information about DBT individual therapy. Finally, we did not correct for multiple comparisons. However, results demonstrate considerable effect sizes for all findings.

DBT individual child therapy and caregiver training component

Our current research focuses on refining skills training for DBT for Children, adapting DBT individual therapy, and developing a caregiver training component via open case studies. Furthermore, we are planning a randomised controlled trial to test the efficacy of the resulting intervention. DBT individual therapy with children will adopt the DBT principles and theoretical framework, while providing children with developmentally appropriate strategies and materials. For example, we developed a ‘Three-Headed Dragon’ board game for behavioural chain and solution analysis. Like other behaviour therapies, DBT uses behaviour analysis to evaluate problems, their antecedents and consequences so as to identify behavioural deficits and to generate adaptive behaviour responses. As with standard DBT, behaviour analysis with children identifies a target from a prioritised list of problem behaviours and balances problem solving with validation of distress. In DBT for Children, behaviour analysis is simplified and follows a specific sequence of links in the chain: event, thought, feeling, action urge, action, and after-effects. This sequence follows a DBT model for observing and describing emotions (Linehan, 1993).

We also initiated the development of caregiver training in behaviour modification and validation techniques. The central notion of DBT is that change can only occur in the context of acceptance. To facilitate children’s adaptive responding, it is imperative to create a validating home environment. Furthermore, in order to effectively reinforce children’s use of coping skills at home, caregivers have to learn DBT skills, as well as behaviour modification strategies. These techniques (see Table 3) were adapted from the Parent Management Training (Kazdin, 2005) and the DBT for adolescents ‘Walking the Middle Path’ module (Miller et al., 2007). In our clinical experience, caregivers indicate that learning DBT skills not only enhances their ability to reinforce children's use of skills but also aids their own emotion regulation. Caregivers note that validating children’s feelings prior to prompting skills use results in higher compliance.

Table 3.

Caregiver training in behaviour-modification and validation techniques

| Introduction to Dialectics | Guiding principals of dialectics (i.e., there is not absolute nor relative truth, opposite things can both be true, change is the only constant, and change is transactional), how these principals apply to parenting, and ways to practice dialectics. |

| Dialectical Dilemmas | Dialectical dilemmas that apply to parenting pre-adolescent children (i.e., permissive vs. restrictive parenting, overprotective vs. neglectful, overindulging vs. depriving, and pathologizing normative behaviors vs. normalizing pathological behaviors). |

| Creating a Validating Environment | Nonverbal (e.g., active listening and being mindful of invalidating reactions, such as rolling eyes and turning back) and verbal validation (e.g., observing and reflecting feelings back without judgment, looking for kernel of truth). |

| Change-Ready Environment | Hierarchy of target behaviors, realistic expectations for change, a need for flexibility and finding a specific approach to each child. |

| Introduction to Behavior Change Techniques | Factors that influence behavior (context, prompts, consequences) and effectiveness of the reinforcement (immediacy, contingency, enthusiasm, quality/type, specificity and consistency). |

| Reinforcement | Create and implement point charts to reinforce the use of DBT skills and other adaptive behaviors, reducing the likelihood of unwanted behaviors by reinforcing alternative adaptive responding. |

| Punishment | Effective punishment (e.g., time out, taking away privileges), and ineffective punishment (e.g., physical punishment) and its negative effects. |

Empirically supported interventions to address pediatric suicidality are urgently needed. Our group has been funded by the National Institute of Mental Health to test the feasibility and efficacy of the adapted DBT in a pilot randomized clinical trial (RCT) with children 7 to 12-years of age exhibiting suicidality and/or self-injury, with history of maltreatment (Francheska Perepletchikova PI). History of maltreatment is one of the most salient risk factors for childhood suicidality and self-harm (e.g. Finzi et al., 2001). The intended study will include 30 children and their caregivers in the DBT for children condition and 30 children and caregivers in the Treatment-As-Usual condition. Further, we are planning a pilot RCT to examine feasibility and efficacy of the adapted DBT with pre-adolescent children placed in residential care due to severe emotional and behavioral dysregulation. Given the impact of early onset psychopathology on development, the main objective of the proposed intervention is to improve the life course trajectory of these vulnerable children.

Key Practitioner Message

Suicidal and self-injurious behaviours in children are on the rise; however, there are no evidence-based interventions to address these problems in pre-adolescent children

Efficacy of DBT for adults and adolescents holds promise for adapting DBT for affected children

Preliminary results on feasibility, acceptability and efficacy of DBT adapted for children are promising and warrant further research with children with more severe clinical impairment

Appendix A: Examples of experiential exercises

1. Balancing a feather

Participants are given a peacock feather and are asked to balance it on a tip of an index finger, whilst avoiding bumping into each other.

Aspect of mindfulness taught: Participating one-mindfully and non-judgementally

2. Balancing act

Participants are asked to balance on one foot with their eyes open and then closed. Participants are instructed to notice the difference in their ability to keep their balance.

Aspect of mindfulness taught: Participating one-mindfully and non-judgementally

3. Tickle challenge

Therapists tickle participants on a nose with a feather. Therapists instruct participants that they are just to observe the sensation without trying to change the experience (i.e. scratch the nose).

Aspect of mindfulness taught: Observing one-mindfully and non-judgementally

Aspects of Emotion Regulation taught: The ‘Wave’ skill

4. Bubble challenge

Therapists blow bubbles in the air. Therapists instruct participants that they are just to observe bubbles in the air without trying to change the experience (i.e. touch/catch bubbles).

Aspect of mindfulness taught: Observing one-mindfully and non-judgementally

Aspects of Emotion Regulation taught: The ‘Wave’ skill

5. Fact or judgement?

Therapist shows a picture of a well-known villain cartoon character and asks participants to take turns describing this character using just facts and non-judgementally.

Aspect of mindfulness taught: Describing non-judgementally and one-mindfully

6. Wrong play

Therapist acts out a negative behaviour or role plays an ineffective use of skills. Therapist asks participants to describe what was done ineffectively and what to do instead.

Aspect of mindfulness taught: Describing non-judgementally and one-mindfully

7. Where do I feel it?

Therapist gives participants blank paper and crayons, and asks them to draw body outlines. Then therapist instructs participants to draw in the outline where they experience emotions (e.g. stomach for anxiety, heart for love). This game can also be used to discuss states of mind (e.g. where each participant experiences each state, such as head for ‘Reasonable Mind’, chest for ‘Emotion Mind’, and stomach for ‘Wise Mind’)

Aspect of mindfulness taught: Describing non-judgementally and one-mindfully

References

- Birmaher B, Brent D, Chiappetta L, Bridge J, Monga S, Baugher M. Psychometric properties of the screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders (SCARED): A replication study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:1230–1236. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199910000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello E, Angold A. Scales to assess child and adolescent depression. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1988;27:726–737. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198811000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finzi R, Ram A, Shnit D, Har-Even D, Tyano S, Weizman A. Depressive symptoms and suicidality in physically abused children. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2001;71:98–107. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.71.1.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresham FM, Elliott SN. Social skills rating system manual. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Services; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Parent management training: Treatment for oppositional, aggressive, and antisocial behaviour in children and adolescents. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Skills training manual for treating borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Murray AM, Brown MZ, Gallop RJ, Heard HL, Heidi L, Korslund KE, Tutek DA, Reynolds SK, Lindenboim N. Randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs. therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:757–766. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AL, Rathus JH, Linehan MM. Dialectical Behavior Therapy: Multifamily skills training group. 2006. Unpublished manual. [Google Scholar]

- Miller AL, Rathus JH, Linehan MM. Dialectical Behavior Therapy with suicidal adolescents. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer CR, Plutchik R, Mizruchi MS, Lipkins R. Suicidal behavior in child psychiatric inpatients and outpatients and in nonpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1986;143:733–738. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.6.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrbeck C, Azar ST, Wagner PE. Child Self-Control Rating Scale: Validation of a child self-report measure. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1991;20:179–183. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler IN, Ayers TS, Bernzweig JA, Wamper TP, Harrison RH, Lustig JL. Children coping with divorce-related stressful events; Paper presented at the American Psychological Association; August; Boston, MA. 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Shields A, Cicchetti D. Emotion regulation among school-aged children: The development and validation of a new criterion Q-sort scale. Developmental Psychopathology. 1997;33:906–916. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.6.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]