Abstract

Primary care settings are the gateway through which the majority of Latinos access care for their physical and mental health concerns. This study explored the perspectives of primary care providers regarding their Latino patients, particularly, issues impacting their patients’ access to and utilization of services. Interviews were conducted with eight primary care providers—and analyzed using consensual qualitative research methods. In addition, observations were conducted of the primary care setting to contextualize providers’ perspectives. Providers indicated that care for Latinos was impacted by several domains: (a) practical/instrumental factors that influence access to care; (b) cultural and personal factors that shape patients’ presentations and views about physical and mental health and treatment practices; (c) provider cultural competence; and (d) institutional factors which highlight the context of care. In addition to recommendations for research and practice, the need for interdisciplinary collaboration between psychology and medicine in reducing ethnic minority disparities was proposed.

Keywords: Latinos, disparities, primary care, qualitative research

The role of counseling psychology in primary care and other medical settings has been highlighted in recent decades in response to alarming trends in physical and mental health among ethnic and racial minorities (Herman et al., 2007; Talen, Fraser, & Cauley, 2005). Compounding these trends is low utilization of physical and mental health services among these populations (Pleis & Lethbridge-Çejku, 2007). The rapid growth of minority populations and the current healthcare reform debate provide an opportunity for promoting multicultural practice and addressing physical and mental health disparities. Counseling psychologists are well-positioned to shape research and clinical practice in these areas due to their expertise in multicultural practice (Herman et al., 2007).

Latinos are one ethnic minority population who are at increased risk for physical and mental health concerns; however, they have historically low rates of seeking services for physical health concerns and even lower rates of seeking services for mental health concerns, particularly in traditional mental health settings (Alvidrez, 1999). Primary care settings are becoming the gateway of mental health services for many Latinos and other minority groups, increasing the relevance of culturally-competent, integrated physical and mental health care (Talen et al., 2005; Vega, Kolody, & Aguilar-Gaxiola, 2001). As counseling psychologists may increasingly work in these settings or in collaboration with providers from those settings, they have an opportunity to increase their understanding of Latinos’ physical and mental health seeking and coping behaviors, as well as determinants of care in primary care settings. This understanding would prepare counseling psychologists and primary care providers to collaborate by engaging in consultation, coordination and co-delivery of care (Herman et al., 2007). Moreover, policy efforts towards integrating physical and mental health care call for interdisciplinary research to inform competence in practice, thus fulfilling an unmet need in both psychology and medicine more broadly (Talen et al., 2005).

Although Latinos are a diverse group with respect to sociodemographic characteristics and physical and mental health outcomes (Vega et al., 2001), disparities in access to physical and mental health care are widely-documented for Latinos, particularly recent immigrants and U.S.-born individuals residing in disadvantaged communities (Pleis & Lethbridge-Çejku, 2007). Overall, more Latinos (17%) than non-Latino Whites (10%) (hereafter, Whites) report their physical health status to be fair or poor, with almost one-third of Latinos (29%) compared to just over one-tenth of Whites (13%), not having a usual place of care (Pleis & Lethbridge-Çejku, 2007). Moreover, although some studies have found lower rates of depression for Latino immigrants than U.S. born Latinos or Whites, studies have consistently found lower rates of mental health utilization for Latinos as a group (Alvidrez, 1999; Lewis-Fernandez, Das, Alfonso, Weissman, & Olfson, 2005).

When Latinos do use mental health services they are more likely to be seen in primary care settings than in specialty mental health settings (Vega et al., 2001). According to a National Council of La Raza (NCLR, 2005) report on Latino mental health, 1 in 11 U.S. born Latinos with a mental health problem seeks mental health services in mental health clinics, as opposed to one in five U.S. born Latinos with a mental health problem who seeks these services in primary care clinics.

Primary care providers are sought out by many Latinos as their first or, in many cases, their sole broker of mental health care (Lewis-Fernandez et al., 2005). First, mental health concerns, particularly depression, may manifest through somatic symptoms, such as headaches, backaches, and stomachaches, or co-occur with medical conditions (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2001). In addition, depression often co-occurs with or results from chronic medical conditions for which Latinos are at high-risk, including diabetes and stroke (Lewis-Fernandez et al., 2005; NCLR, 2005). Second, Latinos’ preference for primary care providers may reflect stigma associated with seeing a mental health specialist (USDHHS, 2001).

In light of Latinos’ utilization of primary care services, this study explored the perspectives of providers in a primary care setting regarding their Latino patients who seek physical and mental health services. Specifically, we sought to understand providers’ views about their patients’ clinical needs, contextual stressors, and access to care. Supplementing and contextualizing providers’ views were field observations of the primary care setting. Through a focus on these issues, this study highlights the physical and mental health needs of Latinos and the factors that influence access to and utilization of care. Further, this study describes the implications of these factors on providers’ approach to treatment of Latinos. This study aims to inform the work of primary care providers and counseling psychologists with Latinos and to promote clinical and cultural competence in the provision of care.

Factors Influencing Access to Physical and Mental Health Care

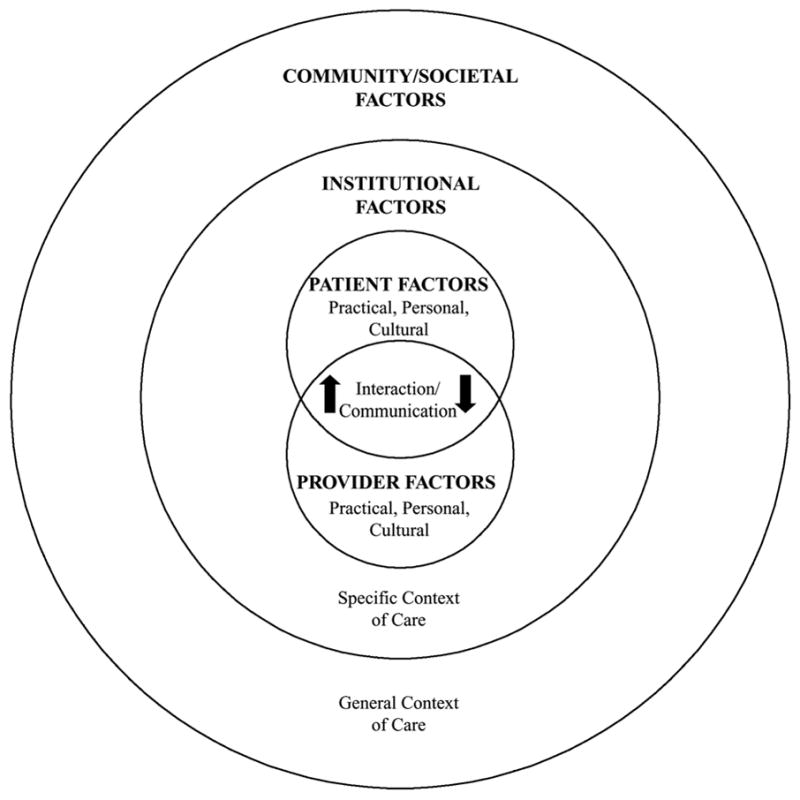

This study’s approach to understanding factors influencing access to care is guided byBronfenbrenner’s Social Ecology Model (1979), in which individuals are part of ever-broadening levels of contexts (e.g., family, community, institutions, society). This model has been successfully applied to a myriad of areas including physical and mental health in primary care, to illustrate determinants of disparities in care from the most narrow factors (e.g., patient and provider characteristics as microsystem) to broader institutional factors (e.g., primary care setting as mesosystem), to even broader community and societal factors (e.g., neighborhood, U.S. health care model as macrosystem) (Talen et al., 2005). Thus, our study proposes that access to physical and mental health services in primary care settings serving Latinos is influenced by a variety of broadening individual and contextual factors, such as instrumental-, personal-, provider-, and institutional-level factors.

Instrumental-level factors refer to resources needed to access care such as language proficiency and insurance (Alegria et al., 2002; Alvidrez, 1999). Approximately 40% of Latinos in the U.S. either do not speak English or have limited English language skills (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000). Limited language proficiency among Latinos decreases access to care, increases discontinuity of care (Pippins, Alegria, & Haas, 2007), and decreases patient satisfaction during patient-provider communications (Lewis-Fernandez et al., 2005). Unfortunately, there exists a significant shortage of Spanish-speaking providers to overcome these barriers (Ruiz, 2002).

In addition to communication difficulties, finances are a salient instrumental factor for Latinos that affect their access to care. For example, many more Latinos lived in poverty (22%) and were uninsured (32%) than Whites (8% and 10%, respectively) in 2007 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2008). These statistics are alarming given that insurance is associated with seeking services for physical and mental health concerns (Alegria et al., 2002).

Personal-level factors or characteristics of the patient, such as manifestation of and culturally-shaped beliefs about illness and treatment are also important contributors to access to care. For example, despite the somatic manifestation of depression, Latinos are also more likely to view depression as a reaction to stress or problems in their relationships with others, rather than as a biologically-based illness (Lewis-Fernandez et al., 2005). Given this externally-based explanation of depression, Latinos often prefer individual treatment or psychoeducation over medication management (Alvidrez, 1999). Latino cultural values, which can protect Latinos from negative physical and mental health outcomes, can also be a barrier to seeking professional services when needed. These values include family obligations and responsibilities, dependence on family and close relatives to solve problems, fatalismo (fatalism) and strong adherence to religion (Bledsoe, 2008).

Provider-level factors or characteristics of the provider, also impact access to care for Latinos. For example, ethnic and language matching of providers to patients is associated with greater treatment satisfaction (Sue, Fujino, Hu, Takeuchi, & Zane, 1991). Despite the favorable outcomes associated with ethnic matching, however, it is estimated that only five percent of physicians in the U.S. are Latino (Ruiz, 2002). The ratio of Spanish-speaking primary care providers to monolingual Spanish patients across the nation is dramatically insufficient given the high proportion of Latinos who do not speak English (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000).

Cultural competence, another provider-level factor, is a dynamic and ongoing process that involves (a) active self-awareness of one’s own beliefs and of cultural exchanges in the patient-provider interaction, (b) knowledge of differences between groups and within groups, and (c) application of this knowledge in clinical practice, also known as skills (Mahoney, Carlson, & Engebretson, 2006). Provider cultural competence is beneficial in that culturally competent providers are more likely to advocate for culturally competent institutional practices, such as diversity trainings and community outreach (Betancourt, Green, Carrillo, & Ananeh-Firempong, 2003; Paez, Allen, Carson, & Cooper, 2008). Thus, cultural competence is more than language fluency and is a critical dimension of service that influences diagnosis and treatment of Latinos (Mahoney et al., 2006). Improving providers’ cultural competence is important given many providers are under-detecting and under-treating their Latino patients, particularly those with mental health needs (Lewis-Fernandez et al., 2005).

Institutional-level factors or organizational and structural practices of the clinical setting, also explain physical and mental health service utilization by Latino patients (Betancourt et al., 2003). Three salient institutional-level factors influencing utilization of services are the composition of the agency, the availability of Spanish-language services, and the length of patient visits. First, Latinos are more likely to seek services for physical and mental health concerns from clinics with ethnically- and racially-diverse staff. These clinics are perceived by patients as promoting culturally-competent services through increased awareness and dialogue about diversity, concerted efforts towards ongoing provider training, and culturally-relevant materials for patients (Paez et al., 2008).

Second, primary care clinics that offer bilingual services are more likely to provide appropriate care to monolingual Spanish-speaking patients than clinics that offer English-language services only (Pippins et al., 2007). Third, the high clinical demands placed on providers often lead to shorter patient visits (Mason et al., 2004), thus limiting the amount of time that physicians can spend on exploring their patients’ concerns. Such time limitations may discourage patients from raising all of their concerns, but particularly their mental health concerns.

This study aims to highlight the critical need for culturally competent services in primary care. It explores the perspectives of primary care providers of the clinical and social needs and the determinants of care of their Latino patients with physical and mental health concerns. A qualitative methodology was particularly suitable to this study as we sought to (a) identify and understand the care issues relevant to a typically understudied and underserved population (Latinos) in primary care, (b) illuminate the perspectives of primary care providers who increasingly and regularly face decisions about physical and mental health care for their Latino patients, and (c) document the experiences of some local providers to aid in the development of programs that are relevant to effectively serve a local community. Thus, this methodology aims to capture the personal meaning underlying the stories of the study’s participants and inform the development of theory (Hill et al., 2005) in relation to patient-provider care interactions.

Methods

Setting and Participants

This study took place in a university-affiliated family medicine clinic located in a low-income urban community in the Midwest. The Latino population (23,159 in 2007) in this community increased by nearly 250% over the last two decades (Dane County Department of Human Resources, 2008). Eleven providers who worked with Latino patients in this clinic were invited to participate. Eight providers, six of them family medicine physicians, one medical resident, and one social worker, participated in interviews; the other three did not participate due to scheduling conflicts. The eight participants constituted an acceptable sample size based on recommendations by Hill et al. for obtaining stable results (2005). Each participating provider spoke fluent Spanish and served Latino patients at the clinic. Half of the providers had a Latino client base of 50% or more. Forty-percent of the clinic patient population was Latino (primarily Mexican and Puerto Rican). The remaining 60% were of varied ethnic backgrounds (i.e., White, Hmong, African American).

Three of the eight providers identified themselves as Latino and the remaining five self-identified as non-Latino White. Ranging in age between 28 and 64 (M = 37.00, SD = 11.72), five providers were female and three were male. Providers’ length of employment in the clinic ranged from 1 to 14 years (M= 5.50, SD = 4.84).

Procedure

Interview team

The interviewers included one medical student and two counseling psychology doctoral students. All shared interests in studying disparities in care. Students had limited experience working with Latino populations and were trained and supervised by the first and last authors, who have advanced degrees in Psychology and Consumer Science, respectively, and both have training in Public Health. These two authors have experience in physical and mental health disparities, community-based participatory research, and qualitative methodologies. The interviewers and one of the investigators identified as White, and the principal investigator identified as Latina. The authors came into the study with the belief that many Latinos experience disparities in care and that some providers struggle to provide culturally-competent care with Latino patients. Acknowledging that these beliefs might bias data collection (i.e., choice or emphasis of questions) or analysis (i.e., selectivity or interpretation of categories), the authors recorded their preexisting beliefs and biases on a daily basis and openly discussed these during research meetings to maximize objectivity. Further, maintaining a focus on the purpose of the study—to explore providers’ perspectives about disparities and care—and thus generating open-ended questions geared toward exploring these perspectives rather than imposing the researchers’ assumptions about them, helped to circumvent bias.

Recruitment and interviews

After approval from the Institutional Review Board of the researchers’ university was secured, providers were recruited through email communication and during clinic staff meetings. Interviews were presented as voluntary, with a $10 gift card offered as an incentive for participation. Providers were then mailed a seven-item demographic questionnaire regarding their age, race, sex, education, medical training, length of employment at the clinic, and estimated percentage of Latino patients on their caseload. At a later date, individual, in-person interviews lasting approximately 60 minutes (from 45–90 minutes) were conducted by an interviewer with each provider. The interviews were designed to elicit descriptions of the providers’ experiences with their Latino patients (questions focused on clinical and social needs, barriers and facilitators to care, and communication patterns). See Table 1 for the interview protocol.

Table 1.

Interview Questions

| 1. Tell me about your work at this clinic. |

| 1a. What is a typical day like for you? |

| 2. Tell me about your patients. |

| 2a. What are your patient’s needs? |

| 2b. What do most of your patients come in for? (most common complaint?) |

| 2c. What is the most common mental health issue? (How is it recognized?) |

| 3. What are your patients’ barriers to health care and mental health care? |

| 3a. What makes it easy/difficult for patients to access care? |

| 5. What are the training needs in your clinic? |

| 6. How would you like this interview to help your clinic? |

Note: Questions were first asked about patients in general, and then about Latino patients. Follow-up questions were asked only if topic was not raised by interviewee.

Clinic observation

To supplement and contextualize providers’ perspectives about their Latino patients, non-participant observations were conducted prior to and following the interviews. A total of 10 hours of observation in 2-hour segments were carried out at different times of the day by one author over five visits. Observations were unstructured, that is, they did not follow a list of pre-determined behaviors. Rather, observations aimed to form naturalistic impressions of patient characteristics and interactions as they emerged in a primary care setting (Mulhall, 2002). Notes were not taken during the observations to avoid any possible discomfort for patients or their family members. However, thorough field notes were drafted immediately after the observations occurred. Observations were made only in the clinic waiting area to minimize any disruption to patient care delivery.

Analysis of Interviews and Observations

Consensual Qualitative Research (CQR) was used to analyze and interpret the interviews (Hill et al., 2005). Theoretically, CQR borrows from several qualitative methods (e.g. phenomenology, grounded theory, and comprehensive process analysis) with an emphasis on consensus among judges (Hill et al., 2005). CQR primarily holds a constructivist view of reality (with some postpositivist views) in which there are multiple, valid “truths” in individuals’ experiences and experiences are often shared among individuals (Hill et al., 2005).

CQR was chosen for this particular study for several reasons. First, the methodology was congruent with our study because it was initially theorized by Hill et al. (1997) to study practitioners’ perspectives on working with particular populations. Second, CQR has several strengths above and beyond many other qualitative methodologies. For example, CQR prescribes very clear methods and steps for researchers, and the process involves extensive training. Additionally, consensus coding is used during each of the phases of coding—this reduces the impact of individual researchers’ biases and ensures that the data is being derived from a more neutral stance, and thus is more valid. We also believe that the use of auditors is a strength of CQR. Not only does consensus coding help with the neutrality of the research, but having an auditor provide feedback as an “outsider” to the study also ensures rigor and validity for the finalized data. Last, this particular methodology uses a “bottom-up” approach, where the domains are first extracted from the data, and so on. While most other qualitative methodologies use a top-down approach (e.g., starting small and then ending up with the larger themes), CQR’s approach differs in that it allows for researchers to define the focus of the study more completely and to ask questions about inconsistent data (Hill et al., 1997).

Data analysis in CQR involves three steps: (a) interview data is grouped or clustered into domains, (b) core ideas within domains are derived to capture the essence of statements in fewer words and with greater clarity, and (c) a cross-analysis is used to construct common categories across data from multiple participants (Hill et al., 2005). Each transcribed interview was thoroughly read and analyzed by units (lines and paragraphs) independently by each research team member. Next, consensus was reached regarding the meaning of coded units in every interview, followed by changes to the domains and categories as per the team’s agreement. Categories were assigned to a single domain and excluded from other domains. Commonality of categories across participants identified the salience of key concepts.

Rather than reporting frequency or percentage of categories, we used narrative labels of “general,” “typical,” and “variant.” A “general” category is when all or all but one provider endorsed an idea that corresponded to a category. A “typical” category included ideas shared by more than half of the providers up to the cutoff for “general,” whereas a “variant” category reflected the ideas of two or more providers up to the cutoff for “typical.” Single cases were not included in the results. Although it was determined that the categories were stable (no new categories emerged and no category ratings shifted) after seven cases, we included all eight cases in the analysis to maximize the richness of the data.

Clinic observations were recorded and coded following Mulhall’s (2003) model pertinent to medical settings. Observations consisted of (a) structural and organizational features (e.g., appearance of clinic building and environment); (b) interactions and behaviors of people; (c) daily activities and operations; (d) special events taking place within daily activities; (e) chronological and daily diary of events; and (f) a personal and reflective diary (e.g., reflections about observations and role of personal experiences in what was observed).

Validity assessment

A variety of post-positivist and constructivist validity assessments were conducted to increase the accuracy of the coding and to reduce researcher bias (Guba & Lincoln, 1994). First, an extensive literature review of physical and mental health disparities for Latinos was conducted in psychology, public health, and medical journals to confirm our general categories. Second, the transcripts and coding of the interviews were returned to the providers to assess for errors, inclusions, and/or exclusions. Resulting revisions led to providers’ constructions being expanded. Third, two independent auditors with expertise in qualitative research and minority disparities (neither of whom were involved in the data collection and coding) checked the final categories against the raw data. They assessed whether data stability had been reached and whether the categories were characterized under the right domains and labeled to faithfully represent the data. Finally, interviewers and observers kept a self-reflective journal documenting their expectations and biases about the research. These expectations and biases were discussed as a team with respect to whether and how they might influence the conduct of the interviews and observations and the interpretation of findings.

Results

Observations of Setting

In the first observation (prior to provider interviews), the first author met several administrative staff and physicians and received a tour of the clinic. The clinic was located in a two-story building on a busy street across from a prominent community center, which serves a large Latino and Southeast Asian population. The facilities were clean and modestly decorated, with bilingual materials and ample furniture in the waiting area. The facilities included a registration area, two waiting areas, a triage desk, exam rooms, administrative offices, a computer room, and a conference room on the second floor. In addition, the psychologist’s and social worker’s offices were located on the main floor. Besides the physician who led the tour, none of the other providers knew in advance of this initial visit. Upon introductions, the staff appeared to be friendly and eager to participate in the study. Providers were observed interacting with their patients in the triage area and interactions appeared to be personable and respectful.

The remaining four observations took place after the provider interviews and were restricted to the waiting room of the clinic. The waiting room had approximately 25 chairs, 4 small tables, and a play area for children. At any given time during the observations, there were no more than 10 patients in the waiting room. Approximately half of the patients observed was Latino and the remaining half was White or African American. There was limited interaction between patients from different racial groups. Many of the Latino patients appeared to be of low-moderate economic resources, many of them arriving accompanied by adult or child family members.

Upon arriving, patients registered in the reception area. They provided personal information and, in some cases, insurance identification to staff. Some Latino patients spoke limited English but others spoke to bilingual staff in Spanish. Once registered, patients were directed to the waiting room, where they were typically called by the nurse approximately 5–15 minutes later. The nurse accompanied patients to the second waiting area by the triage desk and the approximate wait time for patients to see their physician was not observable.

Although the observer did not intentionally interact with patients, there were a few instances in which patients greeted the observer and asked her questions about her country of origin and length of residence in U.S. Unsolicited, one patient shared his immigration story with the observer. Operations and daily activities were fairly consistent from one observation to another, with the exception of one time in which a student (from another study) was recruiting patients in the waiting room.

Provider Interviews

An analysis of the provider interviews resulted in the identification of four domains that reflect components of the physical and mental health care experience for Latino patients: (a) practical or instrumental factors which both hinder and facilitate Latinos’ access to and use of services, (b) cultural/personal factors that relate to patients’ presentations and views about physical and mental health issues, as well as influencing treatment practices, (c) provider factors which shape their work and shed light on the context in which it occurs, and (d) institutional factors which further highlight the context of care. These domains (and their subdomains) are summarized and illustrated with quotes below (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Providers’ Perspectives about Latinos’ Access to Health and Mental Health Care

| General | Typical | Variant | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PRACTICAL/INSTRUMENTAL DOMAIN | |||

| Barriers to physical health care | X | ||

| Barriers to mental health care | X | ||

| Facilitators to care | X | ||

| CULTURAL/PERSONAL DOMAIN | |||

| Physical health | X | ||

| Mental health | X | ||

| Social context and its influences on health and care | X | ||

| PROVIDER DOMAIN | |||

| Provider experience with Latino patients | X | ||

| Provider responsibilities | X | ||

| Provider’s role in mental health concerns of patients | X | ||

| Provider’s role in overcoming barriers to care | X | ||

| Providers and research | X | ||

| INSTITUTIONAL DOMAIN | |||

| Clinic characteristics and role in eliminating barriers | X | ||

| Communication/language at clinic | X | ||

| Training needs | X | ||

Practical/Instrumental Domain

Barriers to physical health care

Providers reported many practical or instrumental barriers they believed Latino patients faced when accessing and utilizing services for physical health issues. Citing issues related to insurance and the cost of care as major barriers to care, many of the providers’ Latino patients were not insured and could not afford to pay for services out-of-pocket. Despite a few patients having insurance, patients’ coverage was often inadequate for all necessary services. A physician gave a detailed and poignant example of such challenges when she stated:

There are always issues of coverage of the visits itself when they’re coming in….I wrote out a medication for a patient whose baby was born and the baby needed the medication but was not yet on the medical assistance and she called me later and said “I’m going to have to pick it up later because I don’t have money to pay for it because he’s not on the insurance yet” …. I found a lesser expensive alternative, but she still had to pay out of pocket for it.

Cost of care made it difficult for patients to pay for their medications, compromising their physical health and that of their loved ones. As exemplified in the quote above, the patient’s limited finances also impacted care delivery, given that the provider took on additional work in an effort to assist her patient (i.e., looking for less expensive medications). This provider also articulated how she struggled with how to provide guideline-concordant care in light of her patient’s limited finances:

I saw a man who hadn’t been seen by a doctor for a lot of years and I said [to patient], “you know, you should come in for a physical at some point and then I can check your cholesterol” and then I looked and saw he didn’t have any insurance, but I said, “it’s sort of up to you because I know it can get expensive coming in for visits like that” and you end up having to not do a lot of preventive care that you know that the guidelines say you should do. But is it better to know what somebody’s cholesterol is right now, or is it better for them to be able to pay the rent and not get evicted? And I would argue that they need to pay the rent and not get evicted…. You have to prioritize things and try to be creative in how you put the guidelines into place when the [patient] is in front of you.

A related practical barrier that providers described being an issue for Latino patients was timing of visits. Many of the providers stated that patients often have long wait times to see their doctor. As many of their patients often work multiple jobs and/or have jobs without leave benefits, these providers worried it could be an economic burden for patients to try to see their doctor during the clinic’s hours of operation.

Although insurance, cost of care, and timing of visits were the barriers to care most commonly reported for physical health concerns, providers also perceived that Latino patients’ lack of knowledge and understanding about the U.S. healthcare system and how to use it effectively was also a barrier to quality care:

They may not know the resources, may not understand the difference between the emergency room and actually even what primary care means to have their own physician….I’d love to care for their diabetes; [but they] just need to follow up on a regular basis.

Barriers to mental health care

Providers described specific barriers pertaining to Latino patients’ access and utilization of mental health services. Although some of the categories were similar to those that emerged regarding physical health barriers (e.g., insurance and language barriers), a few providers pointed out the increased saliency of these issues for accessing mental health care. Language barriers rendered mental health care especially difficult, as emotional and psychological issues are often more complex and difficult to describe or translate than are physical health concerns. Although all of the study’s providers spoke Spanish fluently, several described how linguistic competence is not tantamount to cultural competence. They expressed uncertainty regarding their abilities to understand the meaning of various psychological constructs across different cultures. The providers acknowledged that while translation services were available to them (to use with patients who spoke languages that they did not) several asserted that translation via a third party is especially difficult for mental health services, given the sensitivity of the issues:

There are certain issues that are so intimate and private that for many persons to be there and to tell [an interpreter] that they don’t even know makes them feel uncomfortable. So trying to establish that rapport and trust … is very difficult because there’s one more thing between you and the patient. A patient says that they are very sick and they’re going to die and also that their dog died and the interpreter doesn’t say that they are sad because their dog died and for me knowing that is very important but for the interpreter it isn’t.

The lack of mental health resources, in combination with lack of insurance and language services, intensifies barriers to mental health care for Latinos. Specifically, low-cost mental health services for uninsured patients or mental health services in Spanish were particularly limited and in high demand. The providers lamented how the lack of resources often resulted in extraordinarily long wait times for mental health services, acute crisis services only, less-than-optimal care delivery services (e.g., via translation or primary care providers attempting to treat mental health problems beyond their expertise), or receiving no services at all. As a provider noted:

She was here on a Friday at 5 o clock … and she was in the exam room with the resident, just crying, sobbing, and she’s having post-partum depression. She was with her husband, the baby, and basically was having thoughts of hurting herself and the baby. She didn’t have any insurance and we called the [mental health agency] crisis line and basically asked if this is a phone number we can give her for part of her plan for the weekend, if she’s feeling bad. And they basically said, “well, we don’t have anyone available … who speaks Spanish [and] we don’t use a language line.” So I just thought, “I hope she doesn’t hurt her baby this weekend!”

Practical facilitating factors

In addition to describing barriers, some of the providers addressed facilitators, or factors that assisted Latino patients with access to and utilization of services for physical and mental health concerns. As they did with identifying barriers, providers identified both physical and mental health facilitators. Interestingly, the majority of facilitators for care were the direct reverse of aforementioned barriers.

For physical health care, a few providers asserted a belief if their Latino patients better understood the U.S. healthcare system (e.g., where to go for preventive care versus emergency care), this would result in improved service utilization. The implication for many providers was that their practice needed to extend to the community through education and outreach initiatives, which a few of the providers in this study were already using. Providers also identified several other facilitators for physical health care, such as interpreter services or services in Spanish, and a positive healthcare environment (i.e., friendly and respectful staff). Regarding mental health, providers stated that expanding the primary care setting into a “medical home”, a conveniently-located hub that offers an array of medical and mental health services, would help Latinos access specialized mental health services more readily. One of the providers offered the following:

Having a medical home … means having a place that is friendly, finding people within it who … understand you. But where do you start [if you have a mental health concern]? If you don’t have a place to start then you are adrift and you use the system wrong and you may see all sorts of barriers that may or may not be there. Where you go for that should be your medical home, not a psychiatrist office … because most [specialists] don’t take one insurance, or another insurance. If we feel like [you] need somebody to work with, or [you] would benefit from a more intensive talk therapy or … a particular drug; having someone who can help you find your way through the maze is what everybody needs, mental health or anything else.

Although mental health services were not available for Spanish-speaking patients at the clinic, providers were hopeful that the clinic would expand its staff and services in the future to offer patients a “medical home” for their physical and mental health needs. Providers asserted that being gatekeepers of their patients’ physical and mental health needs would significantly improve access to and quality of care for many Latino patients.

Cultural/Personal Domain

Cultural/personal factors pertaining to physical health

Many of the providers discussed cultural and personal factors which they believed influenced Latino patients’ presentation of concerns and practices as they pertained to physical health. Several providers reported that the majority of their patients seek obstetrical, prenatal, and pediatric services in addition to services for chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, and arthritis. Regarding Latino patients specifically, providers reported that Latino men and undocumented immigrants often only seek services for chronic or severe issues, such as diabetes, HIV, and tuberculosis.

A few of the providers discussed their Latino patients’ practices related to seeking services for physical health concerns which included patient expectations, cultural values and related practices, and knowledge. A prevalent Latino patient expectation which influenced care pertained to addressing multiple issues in one visit, which often resulted in more expensive patient visits and less thorough examination of the patients’ primary concerns. One physician also asserted that, “because some Latino patients have negative experiences with the healthcare system, they begin the clinic visit with strong emotions and expectations that it will be similar to their past experiences.” Other providers discussed how Latinos tend to be less proactive about and have more paternalistic views toward healthcare in general, and that they expect providers to tell them what’s wrong and what to do. Such a paternalistic healthcare model was assumed by providers to be more prevalent in many of their Latino patients’ country of origin.

Patients’ cultural values were also perceived as often influencing patients’ practices and orientations toward physical health care and providers. For example, a provider reported that, while her Latino patients appear to interpret professional boundaries differently than do other patients (e.g., they bring gifts to providers, and come to the clinic without scheduling an appointment), they also tend to be more deferential and evidence a clear respect for providers’ authority. For example, she described an interaction in which a Latino patient appeared hesitant to sit in an available comfortable chair, as if they assumed that it was the provider’s chair and did not want to be presumptuous in sitting in it. Finally, providers discussed how patients’ lack of knowledge about the U.S. healthcare system can lead to difficulties in navigating the system successfully. For example, providers indicated that patients often are unaware that they need a prescription for many medications.

Cultural/personal factors pertaining to mental health

Providers reported depression, anxiety, and stress as the mental health concerns most commonly seen in their Latino patients; however, their perceived prevalence of concerns was inconsistent. For example, one physician reported that mental health concerns were less prevalent among Latino patients than for other groups, while another perceived her Latino patients to be more depressed than other patient groups. Furthermore, providers described gender -related patterns in presentation of mental health. One physician reported seeing Latino men with anxiety and embarrassment about sexual performance and its related cultural expectations, while others discussed how Latina women tend to be stressed and depressed due to social isolation and lack of support, separation from family (especially for first-generation immigrants), and negotiation of childcare and work responsibilities. Providers also described how Latinos often present with vague, somatic concerns (e.g., stomach or chest pains), which upon further investigation reveal depression or other mental health concern. Detailing this process with Latino patients, one physician stated:

They’ll often come in with vague complaints … and you kind of think to yourself, why are they coming in for this? … And then when you sort of delve into their concern—how they’re reacting to you telling them that it’s a rash that will go away on its own and it doesn’t need any treatment—and you start to get a sense of them feeling like they are looking for more out of the visit and then we’ll start to see if there’s anything else going on. And usually I’ll ask about stress and sort of get into the depression questions.

The majority of the providers identified Latino patients’ perceptions of mental health, and beliefs about cultural stigma, as influencing a patient’s orientations toward and participation in care. For example, one physician asserted that Latino patients viewed depression as simply a part of life that they can live with, rather than a medical issue they should be concerned about. Interestingly, providers had different views about the cultural stigmas associated with depression and mental health care. A few providers, for example, reported that such stigmas do exist in the Latino culture. However, one provider reported not perceiving stigma among his Latino patients about mental health and its care:

By the time I’m dealing with somebody [with] mental health concerns, they’re interested in getting some help … it’s more common [that] someone wants help and it’s not available than we’re giving help and the patient doesn’t want it because of stigma.

A few providers discussed their Latino patients’ practices regarding mental health care, particularly depression, which included resistance to, adherence, and follow-through with treatment. One provider, for example, asserted that Latino patients do not come in for depression concerns, talk about depression during visits, or follow through with depression care. A few providers reported that they believed that Latino patients tended to adhere to antidepressant medications less than other patient populations because Latinos don’t believe the medications will help or hold misunderstandings about how these medications work.

Social context and its influence on physical and mental health and care

Finally, a few of the providers discussed aspects of the local Latino community and broader society which influence Latinos’ physical and mental health and care utilization. For example, one provider posited that Latinos in town lack a local community, which makes it difficult for providers to offer centralized services, outreach, and education. Another provider stated that lack of resources in the community impacts physical and mental health more than race and ethnicity, and that understanding facilitating factors (e.g., social support) will help providers work better with their Latino patients.

Of the providers who reported community and societal factors that influence care for Latinos, the majority addressed them as stressors. Immigration and documentation status were identified as primary stressors. For instance, they perceived their Latino patients contending with concerns of trust and fear of deportation, lack of medical and educational access, mobility, separation from family and resulting guilt, and employment problems (e.g., long hours, low wages, no benefits). Language barriers, lack of resources such as childcare and transportation (and the resulting social isolation), and traumatic experiences in their countries of origin were also addressed as factors which influence health overall, especially mental health. One of the physicians noted:

Immigration is influencing a lot of the health questions here too. [Patients] are usually putting emphasis on [immigration] because it is causing a lot of stress and questions. [Patients say], “So I go to the hospital but I don’t have … insurance and I’m undocumented and I don’t have a lot of money at home and I have to wait for hours to get to see the doctor …. But if I go back to [country of origin] then we’re all going to die because I can’t afford the things that I need to live. So in order to stay here what that means is that I have to leave my kids … and I’m going to lose my kids because they don’t even know me” … When I think of all these issues, I don’t know how people can live every day with having that in the back of their mind. To survive, to be happy, to go out.

This provider further highlighted the need for providers to be aware of what is happening in their patients’ community, including immigration stressors. She suggested that these stressors need to be addressed within and outside the clinical encounter (through advocacy) to improve patients’ access to care, quality of care and quality of life.

In summary, providers reported patient factors that influenced Latino patients’ presentation of symptoms, definitions of illness and care, and help seeking behaviors. Another important factor raised by providers was their own competence in their work with Latino patients.

Provider Domain

Provider experience with Latino patients

Each provider had experience working with Latino patients and identified the subsequent influence of this experience on their work. Understandably, having an interest in working with Latinos has influenced providers’ professional experiences and commitment to this population, and vice-versa. For example, one provider described his extensive work with Latino patients elsewhere before moving to this community, and how the opportunity to continue practice with and conduct research with Latino patients attracted him to this particular clinic.

Although the providers interviewed spoke fluent Spanish, several questioned their cultural competence to provide services to Latino patients. A few of the providers expressed uncertainty about healthcare practices and the reasons behind them or cultural factors which might influence them (e.g., resistance to treatment, gender roles). Providers also discussed how the meanings of physical and mental health constructs seem to differ across different Latino subgroups (e.g., Mexican, Guatemalan). One of the Latino providers acknowledged that she may often fail to pick up on subtle cues or symptoms expressed in regionally-specific ways.

Provider responsibilities

In response to interview questions about providers’ practice, many providers discussed their professional responsibilities. Overall, the majority of the providers were experienced in family practice, though their responsibilities differed depending on their role in the clinic (e.g., attending physician, resident, case worker). Furthermore, many of them often juggled multiple responsibilities, both in and out of the clinic, including patient care, supervision of residents, research, teaching, administrative responsibilities, and community outreach.

Provider’s role in patients’ mental health concerns

When providers discussed their roles in addressing patients’ mental health concerns, some described offering brief crisis counseling or “life coaching.” However, they emphasized that they do not provide ongoing counseling services. One provider acknowledged that she is not trained to provide mental health counseling, while another reported that she feels comfortable treating clear-cut depression and anxiety pharmacologically, but is less comfortable treating more complex, severe, or chronic mental health issues such as bipolar or psychotic disorders. In cases where patients need more than the providers could provide, most providers refer them to specialized mental health services.

Provider’s role in overcoming barriers to care

Some of the providers discussed their roles in overcoming the access barriers presented above. Because the providers speak Spanish fluently, they reported often doing additional work—making phone calls, filling out paperwork, finding interpreters or services in Spanish—to ensure that their Spanish-speaking patients received the care that they needed. They reported that the additional work on their part is especially necessary in cases where they need to refer Latino patients for specialized services; furthermore, providers expressed the burden of this work on their already full workloads, often resulting in longer, slower, and less efficient services for Latino patients.

Providers and research

Nearly all the providers discussed research, either their own, or their interest in and hope for the success of this study. Regarding their own research, a few providers reported that they conduct research both within this clinic and others, as well as in the community, related to various physical health issues. For example, one provider reported conducting an analysis of medical issues by geographic location; another reported conducting research exclusively with Latinos on issues such as health education. Regarding the current study, several providers viewed it as an opportunity to help serve Latino patients in the community. Many expressed a desire for feedback based upon the results to help them identify deficits and improve their services.

Institutional Domain

Clinic characteristics and role in eliminating barriers to care

Several of the providers discussed characteristics of the clinic which influence care for their patients. According to many providers, multicultural training and patient diversity well-prepares them to deliver services to various populations. They asserted that having bilingual staff—including a social worker and other physicians—greatly improves the services delivered to Spanish-speaking patients. Providers also described the larger role of the clinic to eliminate barriers. One provider perceived the clinic taking an active role in protecting patients from mistreatment in the larger medical community, stating:

We feel much more protective of our patients—Latinos particularly, but a lot of our patients—because they tend to be stereotyped, and they tend to be thought of in lots of ways by the other parts of the medical community. You know, this isn’t a bad town, in any way particularly—certainly not as bad as many other places—but there is a feeling that people have been intimidated, being not welcome and so on and so forth.

Communication/language at clinic

Several providers described the prevalence of Spanish-speaking physicians as communication/language-related facilitators at the clinic. They also pointed out that Spanish-speaking receptionists help facilitate visits as soon as patients call or walk in the door. However, the lack of Spanish-speaking nurses, medical assistants and technicians leaves communication “broken” throughout the visit, rendering simple procedures such as taking vital signs difficult and more complex procedures such as mental health consultations nearly impossible. The overall result, many said, is a reduction in the quality of services provided to patients who speak Spanish, as compared with those who speak English.

Training needs

Most of the providers identified three overall training needs of all the clinic staff to address deficits and improve patient care. Providers cited the first need for in-service training seminars to educate them about cultural issues and culturally-competent care. A second training need noted by providers was specific to mental health issues such as depression identification and treatment. Providers also desired training on how to use certain services such as telephone translation and computerized records (especially, how to involve Spanish-speaking patients when the computerized records are in English). One provider asserted that trainings would be best led by “insiders” who understand the medical field, rather than by academics who may have knowledge of a particular issue but lack an understanding about the context within which the providers work. Another provider pointed out that the best way to increase cultural competence is to immerse oneself in the community (e.g., attend cultural events), and that all providers could benefit from this approach.

Discussion

This qualitative study presented a personal perspective from primary care providers about their Latino patients with physical and mental health concerns in a family medicine clinic. Clinic observations provided a context for providers’ perspectives and allowed for a richer description of their patients and setting. Domains that hindered or facilitated their Latino patients’ access to and utilization of services emerged from provider interviews and included practical/instrumental, cultural/personal, provider, and institutional factors.

These findings are consistent with a social ecological model (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) and the published research on disparities in care for Latinos (Alegria et al., 2002; Betancourt et al., 2003; Ruiz, 2002) in that factors range from narrow, personal influences to broader, societal influences. In figure 1, patient and provider personal, cultural, and instrumental factors (microsystem) directly influence help seeking practices and care. That is, patient’s physical and mental health concerns, their definition of illness and treatment, and personal characteristics, cultural values, and practical resources (e.g., insurance, ability to pay) coalesce with providers’ knowledge of patient concerns, cultural competence, definition of illness and treatment, personal characteristics, and practical resources (e.g., length of visits, other clinic responsibilities). The patient-provider interaction is largely influenced by the match between these patient and provider factors; however, they are constrained by the specific context of the clinic (mesosystem), such as billing procedures, availability of Spanish-speaking personnel, and hours of operation, among others. Finally, larger community and societal factors (macrosystem) provide a general context for institutional and personal factors. These factors are more removed from the patient and provider but could facilitate or hinder care for patients, nonetheless. These factors could refer to the geographical area, community resources for immigrants and minority patients, policies of the clinic’s university setting, and the U.S. healthcare system, more broadly.

Figure 1.

Social ecological model of factors influencing physical and mental health and care for Latinos in primary care

These findings extend beyond the existing literature—which has primarily relied upon quantitative methods—by exploring the personal explanations and meanings that providers construct around these disparities in patient care. For example, it is well known that monolingual Spanish-speaking patients experience longer clinic wait times than bilingual or English-speaking patients (Pippins et al., 2007). Our findings suggest that longer patient wait times may be due to providers spending more time with their Spanish-speaking patients than their English-speaking patients. Thus, longer wait times may also mean longer visit times for Latino patients. Whether longer visit times improve care for Latino patients is unclear and should be explored in future studies. Alternatively, it might be important to explore how to effectively use wait time to advance some of the outreach initiatives noted by providers in our study.

Another example of how this study builds on the previous research is the use of language interpreters in patient care. Providers’ perceptions were consistent with the literature such that patients are more likely to seek and accept care if the provider and other clinical staff speak Spanish (Paez et al., 2008; Ruiz, 2002; Sue et al., 1991). Extending current knowledge, language services (e.g., interpreting, language line) were valued by providers as a facilitator to Latino patients’ physical health care yet were simultaneously perceived as a barrier to providing effective mental health care for Latino patients. According to providers, patients are less likely to express their mental health concerns in front of an interpreter given the sensitivity of these concerns and the stigma of talking about mental health with strangers. Further, providers described interpretive services as disruptive to patient-provider rapport and trust relative to mental health. Providers’ reluctance may result in low use of language interpreting for mental health, which may have implications for the quality of mental health care for Latino patients in primary care settings. An examination is warranted of how interpreting services need to be tailored to improve care.

Providers also found it difficult to fully address the mental health needs of their Spanish-speaking patients due to lack of mental health training and time constraints, which has been found elsewhere (Betancourt et al., 2003). Although they could refer their patients to mental health specialists, providers perceived this option to be less than ideal given the shortage of Spanish-speaking mental health providers in the community, the resulting discontinuity of care, and the long patient wait times to receive specialty mental health services.

Providers cited the lack of centralized physical and mental health services as a major barrier for Latinos’ care. They pointed out that their Latino patients would have better outcomes if mental health services were provided in the family medicine clinic, given the familiarity and convenience of that setting to patients, and the provider continuity and involvement in care. Providers also stated that continuity of care would increase a trusting patient-provider relationship in which to address stressors associated with immigration, discrimination, and employment, among others, that influence patients’ well-being and decisions about care. Finally, a centralized place for care would increase patients’ understanding of the institutional norms of the health care system in the U.S. (e.g., where to go for different types of care). These perspectives highlight recent literature calling for an integration of medical and psychological services (Herman et al., 2007; Talen et al., 2005).

Finally, providers reflected on the increasing complexities associated with serving multi-stressed Latino patients. The combination of a large patient load and limited appointment time negatively impacted a provider’s ability to explore stressors in patients’ lives that could increase risk for mental health problems. Further, because many patients visited the clinic only when their condition was severe, providers were less able to prevent illness and follow-up on their patients’ lives and well-being. Compounding this challenge are the multiple responsibilities many providers identified (e.g., supervision, research, teaching) and the time they also spent advocating for their Spanish-speaking patients. Some providers expressed the need to be flexible with their time so that they could better serve their Latino patients. Although such flexibility could lead to longer and more comprehensive patient care interactions, it could also result in providers running late from one appointment to another, ultimately placing additional burden on providers (and patients).

Despite the multiple intriguing findings described above, our results must be assessed with some limitations in mind. First, the study was exploratory and also solely based on the perspectives of providers in a primary care clinic. Future studies could examine patient perceptions of their physical and mental health and the determinants of care. It is also important to note that the majority of participating providers practiced medicine, taught and conducted research within a university setting – these unique demographic and professional characteristics likely influenced their perspectives and practices, but these factors were not specifically explored. Further, one of the providers interviewed was a social worker and the experiences of this provider, albeit rich, may have been qualitatively different from the medical providers interviewed. Finally, the study took place in a setting that serves primarily low-income Latino patients. Providers’ perspectives about their patients’ needs could differ if they served Latino patients from different socioeconomic backgrounds. Limitations notwithstanding, our findings could be helpful to providers who work in primary care settings that reflect similar patient and provider demographics.

Implications and Recommendations

The findings of this study have important implications for primary care providers and counseling psychologists with respect to clinical practice, education and training, research, and policy related to Latinos in primary care settings.

Clinical practice

Primary care providers, by virtue of where and when they see patients, have a unique opportunity to address disparities in the delivery of both physical and mental health services to Latino patients. To optimize care interactions and outcomes, providers should be familiar with and strategize to address multiple barriers that interfere with Latinos’ seeking care and receiving adequate follow up (Paez et al. 2008). They should recognize coping behaviors and healing practices of Latino patients and the underlying pathways to mental health problems and presentation of mental health symptoms. Due to many stigmas associated with recognizing and acknowledging mental health needs, and the pervasive view of depression as resulting primarily from external factors and social and economic stressors (Alvidrez, 1999), primary care providers are in a position to explore patients’ contexts and validate distressing experiences prior to addressing symptoms (Lewis-Fernandez et al., 2005).

Another clinical implication is the need for counseling psychologists to work closely with primary care providers, including ensuring referral pathways of mental health services for patients (Talen et al., 2005). Collaborative care arrangements could entail consultations about patients’ mental health concerns and coordination and co-delivery of care. These types of collaborations can enhance services to patients with depression, ensure follow through of care for patients, and offer resources to primary care providers that would otherwise require extensive training and time (Herman et al., 2007). In addition to in-house psychologists and psychiatrists and partnerships with outside mental health specialists, nurses could be trained to detect and collaborate with providers on treatment decisions. Further, individuals offering interpreter services should participate in cultural competence training that emphasizes effectively addressing mental health issues to ensure the obstacles identified by providers in this study are minimized.

Counseling psychologists who receive referrals of Latino patients from primary care providers will enhance the care they provide to these patients by understanding patients’ patterns of coping and help seeking in primary care settings that may transfer to their settings, factors influencing patients’ access to and utilization of services, and primary care providers’ roles in and perceptions related to mental health care. In addition, counseling psychologists will greatly enhance their own work with their Latino patients by understanding the vulnerability of co-occurring mental and physical health concerns afflicting this population, thereby increasing the impact of their interventions on patients’ overall well-being.

Training and education

This study has implications for training and medical education related to cultural competence and mental health care delivery services. With a significant shortage of Latino providers who often bring a wealth of knowledge about and interest in serving Latino populations, it is critical that the existing workforce be prepared to work effectively with this patient population (Ruiz, 2002). Student training with case studies and care delivery issues applicable and specific to Latino communities need to be offered. Trainings in public health and public policy (e.g., Manetta, Stephens, Rea, & Vega, 2007) would also assist providers with acquiring familiarity with some of the more common and unique Latino community health care needs and priorities. Training that engages students in conversations about culture, explanatory models of mental health, perceived barriers to care, and communication facilitators in the clinical encounter would be especially valuable (Manetta et al., 2007; Paez et al., 2008). In particular, the providers in this study offered that practice, role-plays, and discussion of clinical case studies, rather than didactic lectures on these topics, would allow application and development of skills and knowledge ultimately useful in practice. Counseling psychologists could lend their expertise in this area by providing training to medical students and primary care providers in the community (Herman et al., 2007).

Research and policy

Although research studies based on quantitative methodologies have contributed to our knowledge about disparities in care among underserved groups, research using qualitative methods to document the personal meaning and constructs of care by providers of Latino patients is missing. Additional research exploring these constructs with patients and families, in particular to explore whether and how perspectives are similar and different, would further inform our knowledge base and contribute to understanding factors that impede or facilitate access to care for Latino patients with physical and mental health concerns. Such research can also be designed to evaluate the effects of primary care interventions on Latino patients who present with mental health concerns. Moreover, as counseling psychology increasingly adopts cultural and multi-disciplinary foci, health disparities research conducted by psychologists in non-traditional settings has the potential to enhance the mental health well-being of individuals (Herman et al., 2007).

Finally, research can inform public policy by informing the development of initiatives and trainings, minimizing barriers, and serve to fund community-based participatory research (see Bledsoe, 2008). Betancourt and colleagues (2003) emphasize that public policies aimed to increase cultural competence in primary care settings need to occur at three levels: organizational (increasing the minority workforce in the medical field), structural (revising process of referrals, hours of operation, availability of cultural and linguistic resources), and clinical (improving patient-provider encounter). Policies at the national and local level could enforce the design, implementation, and evaluation of these interventions and their impact on the quality of care for Latino patients.

The passing of the 2010 Health Care Reform bill offers some exciting potential to enhance the aforementioned organizational, structural, and clinical policies affecting care in primary care clinics serving large numbers of underserved patients. The bill allows for more patients living under the poverty line to be eligible for Medicaid and other types of medical coverage. In addition, the new legislation mandates that mental health and substance use services are provided at parity with physical health services and calls for more integrated mental health and physical services. However it is too soon to tell whether and how the bill will directly impact the physical and mental health of Latino families, nor whether it will advantage undocumented immigrants who are not eligible for Medicaid and who cannot participate in the health insurance exchanges. This will be an intriguing area of future research for policy researchers especially.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jill M. Bluemner for conducting interviews and participating in the initial coding of interviews. We also thank Dr. Alberta Gloria for auditing our coding and reading drafts of this manuscript.

This project was supported in part by grant 1UL1RR025011 from NIH/NCRR, and grants 1P60MD000506 and 1P60MD003428 from NIH/NCMHD.

Contributor Information

Carmen R. Valdez, Department of Counseling Psychology, University of Wisconsin-Madison;

Michael J. Dvorscek, Department of Counseling Psychology, University of Wisconsin-Madison;

Stephanie L. Budge, Department of Counseling Psychology, University of Wisconsin-Madison;

Sarah Esmond, School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

References

- Alegria TM, Canino G, Rios R, Vera M, Cilderon J, Rusch D, et al. Inequalities in use of specialty mental health services among Latinos, African Americans, and non-Latino whites. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53:547–555. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.12.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvidrez J. Ethnic variation in mental health attitudes and service use among low-income African American, Latina, and European American young women. Community Mental Health Journal. 1999;35:515–530. doi: 10.1023/a:1018759201290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, Ananeh-Firempong O. Defining cultural competence: A practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Public Health Reports. 2003;118:293–302. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50253-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bledsoe SE. Barriers and promoters of mental health services utilization in a Latino context: A literature review and recommendations from an ecosystems perspective. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 2008;18:151–183. [Google Scholar]

- Brofenbrenner U. The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Dane County Department of Human Services. Hispanic people in Dane County. Madison, WI: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Guba EG, Lincoln YS. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. The Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. pp. 105–117. [Google Scholar]

- Herman K, Tucker C, Ferdinand L, Mirsu-Paun A, Hasan N, Beato C. Culturally sensitive health care and counseling psychology: An Overview. The Counseling Psychologist. 2007;35:633–649. [Google Scholar]

- Hill CE, Knox S, Thompson BJ, Williams EN, Hess SA, Ladany N. Consensual Qualitative Research: An update. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2005;52:196–205. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Fernandez R, Das A, Alfonso C, Weissman M, Olfson M. Depression in U.S. Hispanics: Diagnostic and management considerations in family practice. The Journal of the American Board of Family Practice. 2005;18:282–296. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.18.4.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney JS, Carlson E, Engebretson JC. A framework for cultural competence in advanced practice psychiatric and mental health education. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. 2006;42:227–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2006.00093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manetta A, Stephens F, Rea J, Vega C. Addressing health care needs of the Latino community: One medical school’s approach. Academic Medicine. 2007;82:1145–1151. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318159cccf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason K, Olmos-Gallo A, Bacon D, McQuilken M, Henley A, Fisher S. Exploring the consumer’s and provider’s perspective on service quality in community mental health care. Community Mental Health Journal. 2004;40:33–46. doi: 10.1023/b:comh.0000015216.17812.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulhall A. In the field: Notes on observation in qualitative research. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2002;41:306–313. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Council of La Raza. Critical disparities in Latino mental health: Transforming research into action. NCLR; Washington DC: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Paez KA, Allen JK, Carson KA, Cooper LA. Provider and clinic cultural competence in a primary care setting. Social Science and Medicine. 2008;66:1204–1216. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pippins JR, Alegria M, Haas JS. Association between language proficiency and the quality of primary care among a national sample of insured Latinos. Medical Care. 2007;45:1020–1025. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31814847be. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleis JR, Lethbridge-Çejku M. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2006. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Statistics. 2007;10:235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz P. Hispanic access to health/mental health services. Psychiatric Quarterly. 2002;73:85–91. doi: 10.1023/a:1015051809607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue S, Fujino DC, Hu L, Takeuchi DT, Zane NWS. Community mental health services for ethnic minority groups: A test of the cultural responsiveness hypothesis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:533–540. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.4.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. American community survey: A handbook for state and local officials. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. US Government Printing Office. Washington, DC: Author; 2008. Current population reports, P60-235, income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Office of the Surgeon General. SAMHSA; 2001. Mental health care for Hispanic Americans. In Mental health: culture, race, and ethnicity. A supplement to mental health: A report of the Surgeon General. [Google Scholar]

- Talen MR, Fraser JS, Cauley K. Training primary care psychologists: A model for predoctoral programs. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2005;36:136–143. [Google Scholar]

- Vega W, Kolody B, Aguilar-Gaxiola S. Help-seeking for mental health problems among Mexican Americans. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2001;3:133–140. doi: 10.1023/A:1011385004913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]