Abstract

Objectives

1) To quantify arm-hand usage of older adults without a disability and to determine the effect of hand dominance, gender and day on hand usage, 2) to determine the factors that predict arm-hand usage. This information will enhance the understanding of the client’s extent of occupational performance.

Methods

Twenty men and 20 women, 65–85 years old, wore 3 accelerometers (wrists and hip) for 7 consecutive days. Manual dexterity and grip strength were assessed. A 3–way factorial ANOVA and multiple linear regressions were conducted.

Results

The activity kilocounts from both wrist accelerometers revealed a significant interaction effect between hand and gender (F(1,190)=24.4, p<.001). Enhanced manual dexterity of the right hand was associated with greater right hand usage.

Conclusion

Arm-hand usage is a novel dimension of hand function which can be used to measure the extent of real-life occupational performance when the client is in his/her home.

Keywords: upper extremity, aging, accelerometers, movement

INTRODUCTION

Arm and hand function has been found to decline with age (Desrosiers, Hébert, Bravo, & Rochette, 1999; Carmeli & Patish, 2003) due to sensorimotor impairments such as decreased motor coordination (Verkek, Schouten, & Oosterhuis, 1990), decreased manual dexterity (Desrosiers et al., 1999; Mathiowetz, Volland, Kashman, & Weber, 1985) and reduced grip strength (Desrosiers et al., 1999; Desrosiers, Bravo, Hébert, & Dutil, 1995; Rantanen, Era, & Heikkinen, 1997; Jansen, Niebuhr, Coussirat, Hawthorne, Moreno, & Phillip, 2008). The arm and hand function of older adults is also reduced due to impairments related to diseases that are frequent in this population such as rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis [affecting 21% of US adults (46.4 million persons) (Helmick et al., 2008)], fractures or neurological conditions such as stroke [affecting about 700 000 people in the USA each year (Rosamond et al., 2007)]. Although specific assessments of arm and hand function have been established [for example the DASH (Solway, Beaton, McConnell, Bombardier, 2002, Box and Blocks (Mathiowetz, et al. 1985)], it is unknown how much healthy older adults use their hands in daily activities. Factors such as grip strength and dexterity may influence arm-hand usage, as well as hand dominance, age, gender and previous vocation. More so, despite the fact that hand strength and dexterity limitations are known to have an impact on activities of daily living (Flunn, Trombly-Latham, & Podolski, 2007) it is not known if the extent of hand usage has an impact on occupational performance. Accelerometers will enable an objective measure of occupational performance at home, where the occupational therapist is not present.

Accelerometers, which measure the extent and intensity of acceleration (movement), are a relatively novel way to monitor arm-hand usage. Traditionally accelerometers have been used to monitor mobility and walking. The reliability and validity of accelerometers for the upper extremity has been established (Uswatte, Miltner, Foo, Varma, Moran, & Taub, 2000; Uswatte, Foo, Olmstead, Lopez, Holan, & Simms, 2005; Uswatte, Giuliani, Winstein, Zeringue, Hobbs, & Wolf, 2006; Vega-Gonzalez & Granat, 2005; de Niet, Bussmann, Ribbers, & Stam, 2007) and accelerometers were found to provide an objective way to assess real-world upper extremity function of subjects outside the laboratory. This finding is valuable especially for individuals with stroke who often experience Learned Nonuse of their weaker upper extremity. Learned nonuse is a well known phenomenon post stroke which describes the disparity between the individual’s motor ability to use the weaker hand to the actual use of the weaker upper extremity post stroke (Taub, 1980). Recently accelerometers have been used to monitor both hands of two groups of individuals with stroke (N=169) in order to measure the compliance of the restraint on the unaffected upper extremity and arm usage on the affected upper extremity before and after participating in constaint induced movement therapy (Winstein et al., 2003; Taub & Uswatte, 2003)] (Uswatte, Giuliani, Winstein, Zeringue, Hobbs, Wolf, 2006). In addition, recovery and hand usage may be linked and a recent study found that those individuals with stroke who used their paretic arm less required increased activation of secondary motor areas (e.g., contralesional motor regions) possibly as a mechanism of compensation (Kokotilo, Eng, McKeown, & Boyd, in press). To date, occupational therapists have no objective measure of how much their clients are using their affected upper extremity outside the clinical setting. The Motor Activity Log (MAL) captures the amount and quality of arm-hand usage at home but relies on self report regarding 14 specific tasks rather than on real-time objective measures (Uswatte, Taub, Morris, Vignolo, & McCulloch, 2005). However, significant high correlations (r=0.81–0.90) between the MAL to the accelerometer reading of the unimpaired arm, impaired arm and ratio of both arms) of 169 individuals with stroke has been reported (Uswatte et al., 2006).

Greater hand usage in the dominant, compared to non-dominant hand has been found during daily living activities in healthy young adults. Vega-Gonzalez & Granat (2005) assessed the usage using an electrohydraulic activity sensor attached to the shoulder and wrist for 8 hours of both arms of 10 healthy young adults performing their normal daily activities. They reported that the dominant arm of these participants was 19% more active than their non-dominant arm. de Niet et al. (2007) used a combined electrogoniometric/accelerometric system for 12 hours to monitor the upper extremity of five healthy participants and found greater activity for the dominant hand compared to the non-dominant hand.

In contrast, arm-hand usage of healthy older adults may be more bilateral. The arm-hand usage was assessed using accelerometers of adults from three age groups (13 adults with a mean of age 25 years, 9 adults with a mean age of 50 years and 14 adults with a mean age of 70 years) (Kalisch, Wilimzig, Kleibel, Tegenthoff, & Dinse, 2006). Over several hours, adults from the oldest group were found to use both hands with equal frequency while the younger subjects used their dominant right hand more than their non-dominant left hand. Lang, Wagner, Edwards, & Dromerick (2007) and Kilbreath & Heard (2005) found similar findings for healthy older adults.

One of the possible confounding factors in assessing arm-hand usage is the influence of gender. It is possible that gender differences in manual abilities, in addition to factors such as social and cultural background may have an effect on the usage of the arm and hand especially during Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) tasks. Many IADL tasks which require arm-hand usage are traditionally considered to be a woman’s role (Allen, Mor, Raveis, & Houts, 2003; Asberg & Sonn, 1998). Older men, though physically capable of doing IADL tasks such as meal preparation and laundry, may rely on their spouses or others to do these tasks for them (Asberg & Sonn, 1998; Koyano, Shibata, Nakazato, Haga, Suyama, & Matsuzaki, 1988). Therefore the influence of gender on arm-hand usage, especially in older adults is important to investigate.

Activities of daily living, IADL tasks, education, work, play, leisure and social participation are all are areas of occupational performance (American Association of Occupational Therapists [AOTA], 2008). Occupational performance is comprised of an objective, observable component and a subjective component, which both must be captured (McColl & Pollock, 2005). Accelerometers can enable an objective measure of the extent of occupational performance at home, where the occupational therapist is not present. This real life measure of “how much” hand usage in conjunction with findings from the clinical assessments will enhance the understanding of the factors that relate to hand usage. In the future the data from accelerometers will demonstrate how diverse impairments may influence hand usage and occupational performance. In addition, accelerometers could be used as a clinical tool by enabling therapists to monitor the amount of clients’ hand usage outside of therapy sessions. This could have a positive impact on clients’ adherence to activity-based “homework programs” as is recommended in task-based training programs to enhance motor skill in patients with mild to moderate hemiparesis after stroke (e.g. Bass-Haugen, Mathiowetz, & Flinn, 2007).

To date, there is no normative data of the extent of arm-hand usage of older adults during daily activities. Thus, we do not know how much older adults use their upper extremities. Obtaining this important information will enable future comparisons of arm-hand usage of older adults who commonly experience impairments of the upper extremities, such as post stroke. More so, hand strength and dexterity limitations are known to have an impact on activities of daily living (Flunn et al., 2007) but it is not known if the extent of hand usage has an impact on occupational performance. Studies have demonstrated, though, that more practice of using the weaker upper extremity post stroke is beneficial for improving hand function (e.g. Barreca, Wolf, Fasoli, & Bohannon, 2003). Obtaining normative data can also be used to guide treatment to increase arm-hand usage and enhance the occupational performance of our clients.

Therefore the primary objective of our study was to quantify hand usage (measured by accelerometers for multiple days) of older men and women without a disability and determine the effect of hand dominance, gender and day (day 1 to day 5) on hand usage. Our second objective was to determine factors (e.g., age, dexterity, hand strength) that predict hand usage using linear multiple regression. Understanding the factors that contribute to hand usage will assist when aiming to increase hand usage and promote occupational performance.

METHODS

Population

Forty community-living older adults (20 men and 20 women) met the following inclusion criteria and participated in the study: 65–80 years of age; right-handed as assessed by the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (Oldfield, 1971) and had full use of both upper extremities. In addition, subjects were all retired which avoided any influence from vocation on arm-hand use. Exclusion criteria were a neurological or psychiatric condition; any impairment that limited their use of the hands such as peripheral neuropathies, osteoarthritis, or rheumatoid arthritis, upper extremity fractures sustained within the last year; not independent in basic activities of daily living (BADL) and IADL.

The study was advertised at community and shopping centers. Subjects were also recruited via snowballing recruitment. Forty three participants expressed a desire to participate in the study, but 3 people were excluded since they did not meet the inclusion criteria (2 were left handed and one had rheumatoid arthritis), therefore 40 subjects were included in the study. This study was approved by the local university ethics board, and all eligible subjects gave written informed consent prior to participating in the study. Subjects were provided with an honorarium for their participation in the study.

Sample size justification

The sample size (N = 40) for this study was calculated using G*Power 3.0 software (Buchner, Erdfelder & Faul, 2008) and was designed to provide sufficient power for three factors [hand (dominant or non-dominant), day and gender] using a 3-way ANOVA with a moderate effect size at 0.30, an alpha of 0.05 and power of 0.80.

Instruments

Accelerometers (Actical™, Mini Mitter Co) quantified the extent of arm usage (the amount and intensity of arm activity) of the subjects using the mean total activity kilocounts per day over 7 consecutive days. The Actical accelerometer is a small (28X27X10 mm), light (17g), waterproof accelerometer which has a frequency range of 0.3–3 Hz, is sensitive to 0.05–2.0 G-force and samples at 32 Hz. It detects acceleration in all 3 planes although it is more sensitive in the vertical direction. When worn on the hip it has a step count function. The accelerometer record is rectified and integrated over the specified window (15 seconds) as activity counts; one kilocount is 1000 activity counts. Thus, higher activity counts would occur with longer usage (i.e, time), more movements (e.g., raking), and greater intensities of movement. Actical was found to be superior to two other most commonly used accelerometers (Actigraph and RT3) for intra-instrument and inter-instrument reliability (Esliger & Tremblay, 2006). A limitation of accelerometers is they cannot detect the difference between a functional task (i.e. eating) to a non functional task (i.e. moving the arm up and down). It is also not possible to detect sustained functions that do not incorporate movement (i.e. holding an object in the hand without moving it). The validity of the accelerometers has been tested by correlating the accelerometer readings of 34 individuals with acute stroke to upper extremity clinical assessments of function (r=0.40–0.62, p<0.01) (Lang et al., 2007). Pretreatment-to post-treatment changes in quality of upper extremity movement scores of 41 patients have been shown to be strongly correlated to the accelerometer readings (r=0.91, p<0.01) (Uswatte, et al., 2005) and strong correlations have been established between accelerometer readings and observer ratings of the extent of arm activity of 9 individuals with stroke (r=0.93, p<0.01) (Uswatte et al., 2000). Discriminative validity of the accelerometers has been established by comparing the level of usage of the affected upper extremity of individuals with stroke to upper extremity usage of healthy individuals (p<.01) (de Niet et al., 2007; Lang et al. 2007). Accelerometers have also been found to be sensitive to reveal differences between the extent of arm usage of the affected and non-affected upper extremity of individuals with stroke (p<.01) (Vega-Gonzalez & Granat, 2005; de Niet et al., 2007).

The Box and Blocks test (Cromwell, 1965) was used as a test of manual dexterity. Manual dexterity is the ability to make skillful, controlled arm-hand manipulation of larger objects (Mathiowetz & Bass-Haugen, 2007). The subject was required to transfer as many blocks from one side of a box, over a divider, to the other side, in one minute. The number of blocks transported from one side of a box to the other in one minute is counted. This test is a reliable and valid test for assessing dexterity in people over 60 years old [ICC = 0.97; ICC = 0.96) for the right and left hand, respectively (Desrosiers, Bravo, Hebert, Dutil & Mercier, 1994)] and has norms for age, gender and hand dominance (Mathiowetz et al., 1985).

Grip strength was assessed with the Jamar Dynamometer. Each hand was assessed three times in a standardized position (Fess, 1992) with the dynamometer handle on the second position. The mean of the three trials was recorded in kg. This test is a reliable and valid test (r>0.08, p<0.01) for assessing manual grip strength in healthy and hand injured populations (Bohannon & Schaubert, 2005; Mathiowetz, Weber, Volland, Kashman, 1984) and has norms for age, gender and hand dominance (Jansen et al., 2008).

Procedure

Participants completed a demographic questionnaire which included questions regarding IADL tasks (such as shopping, laundry and driving) based on Lawton and Brody’s IADL questionnaire (Lawton & Brody, 1969; Lawton, Moss, Fulcomer & Kleban, 1982). Subsequently they were administered the Box and Blocks test and the grip strength assessment. The order of these two assessments was counterbalanced to eliminate possible fatigue.

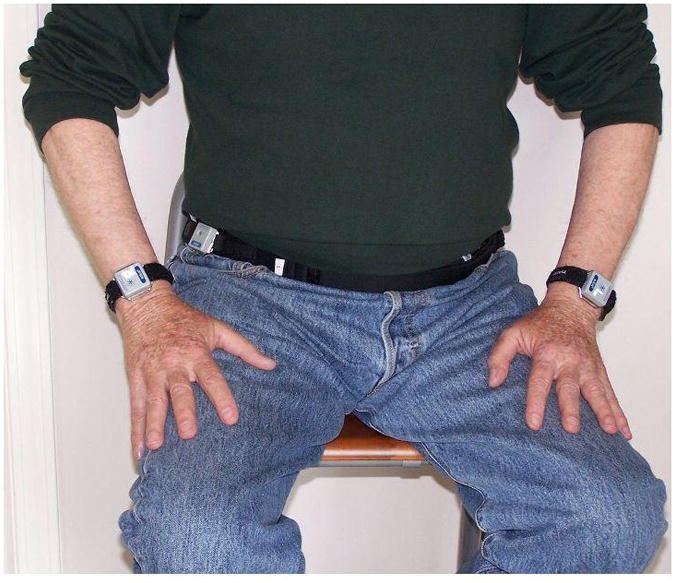

Subjects were provided instruction on the use of the accelerometers. They were given two accelerometers which were worn on each wrist. A third accelerometer was worn on a belt over the right Anterior Superior Iliac Spine to determine when arm activity was occurring while walking versus other tasks (see figure 1). Subjects were requested to wear the accelerometers for all of their waking hours throughout 7 consecutive days starting the next morning, and to go about their normal activities. When subjects returned the accelerometers they were asked if they wore the accelerometers for all 7 days. In addition they were inquired if they slept with the accelerometers on and if they encountered any problems. This was verified with the downloaded data from the accelerometers.

Figure 1. Accelerometer configuration.

Two small accelerometers were worn on each wrist with a velcro watch strap. The right accelerometer was marked with the letter “R” and the left accelerometer was marked with the letter “L”. A third accelerometer was worn on a belt over the right Anterior Superior Iliac Spine.

STATISTICAL METHODOLOGY

The activity kilocounts from the accelerometers over the time period were downloaded to a computer. In order to reveal a “functional” measure of hand usage, we eliminated the activity kilocounts of arm swing while walking. This was calculated as the total activity kilocounts of the hands minus the activity kilocounts of the hands that were done simultaneously when at least five consecutive steps were taken (measured by the step count function). This procedure provided us with “functional” arm-hand usage for the waking hours of 5 consecutive days (since the step count can function for 5 days only). Subjects commenced data collection on different days (between Tuesdays and Saturdays).

To characterize the two groups, descriptive statistics were used. T-tests for independent samples were used to assess the group differences between men and women for age, years of education and years since retirement. The Mann Whitney test was used to assess the differences between the groups (men and women) for dichotomous variables. Descriptive statistics were used to present the mean (SD) activity kilocounts per day for each hand.

To address our first objective of quantifying hand usage and determining the effect of hand dominance, gender and day on hand usage, a three-way ANOVA was performed to assess the within factor of hand (right dominant versus left non-dominant hand), between factor of gender (men versus women) and within factor of day (day 1 to day 5). For the second objective to quantify determinants for hand usage, two multiple linear regressions were used (mean daily activity kilocounts) for the right dominant and left non-dominant hand after accounting for age and gender. To determine entry into the regression model, Pearson correlations coefficient was used to assess the relationships between hand usage to dexterity and grip strength of the right dominant and left non-dominant hands. Correlations ranging from 0.25 to 0.5 were considered fair and values of 0.50 to 0.75 were considered moderate to good relationships (Portney & Watkins, 2009). Variables with significant correlations (p value < 0.05) were entered into the model.

RESULTS

The demographic information of the men and women is presented in Table 1. No significant differences were found between the groups for age, education, and time since retirement. However, significantly more women reported that they cooked (z=−2.4, p<.01) and washed/ironed clothes (z=−0.59, p<.002) compared to men, whereas significantly more men performed home repair activities (z=−2.1, p<.03) and drove a car (z=−2.6, p<.009).

Table 1.

Demographic Information of the women (N=20) and men (N=20)

| Men (N=20) | Women (N=20) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Mean (SD) | Range | Mean (SD) | Range | |

| Age (years) | 72.3 (4.1) | 65–78 | 70.3 (3.2) | 65–77 |

| Years of education | 15.6 (4.0) | 11–24 | 14.5 (3.4) | 13–20 |

| Years since retired | 10.6 (6.9) | 1.5–25 | 10.4 (7.5) | 0.5–27 |

|

| ||||

| N | % | N | % | |

|

| ||||

| Married Yes/No | 14/6 | 70/30 | 15/5 | 75/25 |

| Drive a car Yes/No* | 20/0 | 100/0 | 14/6 | 70/30 |

| Shopping Yes/No | 19/1 | 95/5 | 19/1 | 95/5 |

| Cooking Yes/No* | 11/9 | 55/45 | 18/2 | 90/10 |

| Laundry Yes/No* | 10/10 | 50/50 | 19/1 | 90/10 |

| Home repairs Yes/No* | 8/12 | 40/60 | 2/18 | 10/90 |

| Lawn, yard work Yes/No* | 8/12 | 40/60 | 4/16 | 20/80 |

Significant difference between men and women (p<0.05)

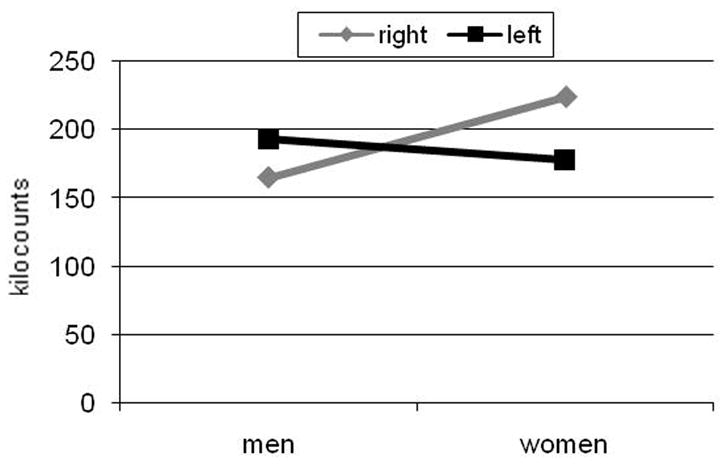

All of the subjects wore the accelerometers for their waking hours during 7 days; some not taking the accelerometers off at all. No technical problems were encountered and no one reported discomfort from the accelerometers. The mean and standard deviation (SD) of activity kilocounts per day for the men’s right hand was 164.9 (76.9) and 193.6 (120.1) for their left hand. The mean (SD) activity kilocounts per day for the women was 224.3 (111.8) for the right hand and 177.7(116.5) for their left hand. In order to determine the effect of hand dominance, gender and day (day 1 to day 5) on hand usage a three-way ANOVA was run. There was no main effect for hand, gender or day but a significant interaction effect between hand and gender was found (F(1, 190)=24.4, p<.001) (Figure 2). The extent that women used their dominant hand is 26% more than men used their dominant hand. On average women used their right hand 21% more than their left hand while men used their right hand 15% less than their left hand.

Figure 2.

The interaction between right dominant and left non-dominant extent of hand-arm usage (activity kilocounts) and gender

For the right hand, a significant moderate correlation was found between increased usage (accelerometer activity kilocounts) (r=.53, p<.001) and increased number of blocks transferred in the Box and Blocks test. For the left hand, a fair correlation (r=.34 p<.001) was found between those variables. A fair significant correlation between hand usage to grip strength was found only for the right hand (r=.33, p<.001). After adjusting for age and gender, the manual dexterity (Blocks and Blocks score) accounted for 18% of the total variance of right hand usage using linear regression (Table 2). The total variance accounted by the final model (age, gender, and dexterity) was 35% of right hand usage. For the left hand, age, gender, dexterity and grip strength of the left hand were not found to significantly predict left hand usage.

Table 2.

Linear Regression Model Summary For Extent of Right Dominant Arm-Hand Usage

| R2** | R2 change | Unstandardized β (standard error) | Standardized β^ | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.572 | ||

| Age | 2.267 (3.976) | 0.095 | |||

| Model 2 | 0.17 | 0.161 | 0.013 | ||

| Age | 4.929 (3.828) | 0.206 | |||

| Gender | 74.203 (28.467) | 0.416 | |||

| Model 3 | 0.35 | 0.180 | 0.004 | ||

| Age | 2.042 (3.565) | 0.085 | |||

| Gender | 49.825 (26.778) | 0.280 | |||

| Dexterity | 5.759 (1.880) | 0.452 |

Note: Grip strength was not a significant determinant (p=0.552) and was removed from the model.

R2 is the coefficient of determination and is the proportion of variability in a data set that is accounted for by the statistical model.

The standardized beta coefficients represent the change in terms of standard deviations in the dependent variable that result from a change of one standard deviation in an independent variable.

DISCUSSION

The dominant and non-dominant arm-hand usage of forty older adults was quantified using triaxial accelerometers over five consecutive days. The swing arm movements during walking were eliminated and thus the activity kilocounts captured functional use of the hands.

While both the men and women were characterized as right handed in terms of ability and functional use, women demonstrated a significant preference of using the dominant hand whereas men presented more bilateral usage of their hands of using their non-dominant hand). For completing everyday, non vocational activities, the extent that women used their dominant hand is 26% more than men used their dominant hand. More so, as may have been expected for the general population, on average women used their right hand 21% more than their left hand. Surprisingly, men used their right hand 15% less than their left hand.

The interaction effect between gender and hand dominance has not been previously explored or analyzed by others (de Niet et al., 2007; Kalisch et al., 2006; Lang et al., 2006; Kilbreath et al., 2005) and may explain the reason that some studies revealed greater hand usage of the dominant hand versus other studies which found equal use of both hands. The traditional roles performed by women (Allen et al., 2006; Asberg & Sonn, 1998; Van Heuvelen, Kempen, & Brouwer, de Greef, 2000) and by men (Jenson, Suls, & Lemos, 2003) were also identified in the current study. Cooking and washing/ironing clothes which are frequently done by women possibly influenced the women’s arm-hand usage, causing the asymmetry with greater dominant right hand usage. Contrary, yard work repairs and carrying which were found to be performed more often by men may include more bimanual tasks which require both the dominant hand and the non-dominant hand to be used simultaneously. More so, tasks performed by women such as cooking and washing are usually carried out daily as opposed to tasks such as yard work repairs, which may be carried out by men less frequently. Another explanation might be that women tend to do dexterous activities, therefore they use their dominant hand more whereas men tend to do strength activities, therefore use their non-dominant hand more often.

The manual dexterity of the right hand accounted for 18% of the total variance of the right arm-hand usage, after controlling for age and gender. This one-time performance on the Box and Blocks test was able to predict the extent of arm-hand usage in the real world setting over 5 days. Although manual dexterity has been found in the past to be a strong predictor of functional independence and disability in BADL and IADL (Van Heuvelen, et al., 2000; Williams, Hadler, & Earp, 1982; Ostwald, Snowdon, & Rysavy, 1989), our study extends these findings to dominant arm-hand usage. As our study is cross-sectional, it is not possible to determine causation. It is possible that old adults who use their hands frequently develop better dexterity, or alternatively, those who have better dexterity do use their hands more. The task of transferring blocks is similar to many daily activities such as packing and unpacking the dishwasher or dealing out cards, which is usually performed with the dominant hand. Of interest, the non-dominant arm-hand usage could not be predicted by dexterity and grip strength.

Although grip strength has been found to be related to a number of important variables, including mortality (Sasaki, Kasagi, Yamada, & Fujita, 2007) and frailty (Syddall, Cooper, Martin, Briggs, Aihie-Sayer, 2003), grip strength was not found to be a determinant of hand usage. One can assume that this is due to the fact that maximum force is not required in everyday life.

Though differences in hand usage have been found between young and older adults (Kalisch et al., 2006), age was not found to be a predictive variable of hand usage in our study. Our study sample included retired older adults ranging from 65 years old (retirement age) to 78 years old which is just within the average lifespan in Canada (Statistics Canada, 2007). Despite this 13 year age range, no relationship was found between age to arm-hand usage. Thus, differences of hand usage between young and older adults may result from the distinct activities of these groups (e.g., vocation) while in our cohort all of the participants were retired. Future studies should include young adults in addition to older adults in order to assess differences in hand usage due to aging.

This study demonstrated that by using accelerometers, the extent of arm-hand usage during real life activities of older adults can be quantified. The accelerometers add a new dimension for hand function; it potentially can enable one to obtain information about the extent of hand usage of clients outside of the clinical settings. This valuable information in conjunction with the information from traditional clinical assessments will hopefully enhance the understanding of how different impairments may affect arm-hand usage of older adults.

The findings of this study also determined that both hands may be used to similar extents for daily function. Awareness of this fact might lead clinicians to focus equally on both hands in terms of actual use and not predominantly on the dominant hand. When possible, individuals should be encouraged to use both hands for daily function and not rely on one hand using compensatory techniques. It also provides support for task-based interventions for individuals with stroke that require bilateral, rather than unilateral arm use. More so, women and men should each be encouraged to practice tasks that are usually performed by them and not generic tasks in order to achieve the balance between the extent of usage of the hands.

Accelerometers would be potentially beneficial to use with diverse upper extremity conditions common in older adults in order to measure arm-hand usage. To date, a few studies aiming to quantify the hand usage of individuals with stroke have been carried-out (Uswatte et al., 2000; Uswatte et al., 2005; Uswatte et al., 2006; de Niet et al., 2007). In order to establish characteristic arm-hand usage for these special populations, additional studies with common upper extremity conditions which affect older adults are warranted. Lastly, longitudinal studies which focus on changes that may occur in hand usage due to normal aging or recovery from injury would be relevant to pursue in the future.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all of the participants for contributing to the study. The support of BC Medical Services Foundation (# BCM08-0098) (to JJE, DR), Post-doctoral funding (to DR) from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, Canadian Stroke Network, Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR)/Rx&D Collaborative Research Program with AstraZeneca Canada Inc. Career scientist awards (to JJE) from CIHR (MSH-63617) and the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research.

References

- Allen SM, Mor V, Raveis V, Houts P. Measurement of need of assistance with daily activities: Quantifying the influence of gender roles. Journal of Gerontology. 1993;48:S204–S211. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.4.s204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Occupational Therapy Association. Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process (2nd ed.) American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2008;62:625–683. doi: 10.5014/ajot.62.6.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asberg KH, Sonn U. The cumulative structure of personal and instrumental ADL: a study of elderly people in health service district. Scandinavian Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 1988;21:171–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreca S, Wolf SL, Fasoli S, Bohannon R. Treatment interventions for the paretic upper limb of stroke survivors: a critical review. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair. 2003;17:220–226. doi: 10.1177/0888439003259415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohannon RW, Schaubert KL. Test-retest reliability of grip-strength measures obtained over a 12-week interval from community-dwelling elders. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2005;18:426–427. doi: 10.1197/j.jht.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass-Haugen J, Mathiowetz V, Flinn N. Optimizing motor behavior using the occupational therapy task oriented approach. In: Radomski MV, Trombly-Latham CA, editors. Occupational therapy for physical dysfunction. 6. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. pp. 598–617. [Google Scholar]

- Buchner A, Erdfelder E, Faul F. How to Use G*Power [WWW document] 2006. Retrieved September 16, 2008, from www.psycho.uni-duesseldorf.de/aap/projects/gpower/how_to_use_gpower.html.

- Carmeli E, Patish H, Coleman R. The aging hand. Journals of Gerontology A Biological Sciences Medicine Sciences. 2003;58:146–152. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.2.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cromwell FS. Occupational therapist manual for basic skills assessment: primary prevocational evaluation. Pasadena, CA: Fair Oaks Printing; 1965. pp. 29–31. [Google Scholar]

- de Niet M, Bussmann JB, Ribbers GM, Stam HJ. The stroke upper-limb activity monitor: Its sensitivity to measure hemiplegic upper-limb activity during daily life. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2007;88:1121–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desrosiers J, Bravo G, Hebert R, Dutil E, Mercier L. Validation of the Box and Block Test as a measure of dexterity of elderly people: Reliability, validity, and norms studies. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1994;75:751–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desrosiers J, Bravo G, Hébert R, Dutil E. Normative data for grip strength of elderly men and women. American Journal of Occupational therapy. 1995;49:637–44. doi: 10.5014/ajot.49.7.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desrosiers J, Hébert R, Bravo G, Rochette A. Age-related changes in upper extremity performance of elderly people: a longitudinal study. Experimental Gerontology. 1999;34:393–405. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(99)00018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esliger DW, Tremblay MS. Technical reliability assessment of three accelerometer models in a mechanical setup. Medicine and Science in Sports Exercise. 2006;38:2173–2181. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000239394.55461.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fess EE. Clinical assessment recommendations. 2. Chicago: American Society of Hand Therapists; 1992. Grip strength; pp. 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Flunn NA, Trombly-Latham CA, Podolski CR. Assessing abilities and capacities: Range of motion, strength and endurance. In: Radomski MV, Trombly-Latham CA, editors. Occupational Therapy for physical dysfunction. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. pp. 91–186. [Google Scholar]

- Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Gabriel S, Hirsch R, Kwoh CK, Liang MHM, Kremers HM, Mayes MD, Merkel PA, Pillemer SR, Reveille JD, Stone JH. for the National Arthritis Data Workgroup. Estimates of the Prevalence of Arthritis and Other Rheumatic Conditions in the United States. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2008;58:15–25. doi: 10.1002/art.23177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen CW, Niebuhr BR, Coussirat DJ, Hawthorne D, Moreno L, Phillip M. Hand force of men and women over 65 years of age as measured by maximum pinch and grip force. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity. 2008;16:24–41. doi: 10.1123/japa.16.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenson M, Suls J, Lemos K. A Comparison of Physical Activity in Men and Women with Cardiac Disease: Do Gender Roles Complicate Recovery? Women & Health. 2003;37:31–48. doi: 10.1300/J013v37n01_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalisch T, Wilimzig C, Kleibel N, Tegenthoff M, Dinse HR. Age-Related Attenuation of Dominant Hand Superiority. PLoS ONE. 2006;1:e90. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilbreath SL, Heard RC. Frequency of hand use in healthy older persons. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy. 2005;51:119–122. doi: 10.1016/s0004-9514(05)70040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokotilo KJ, Eng JJ, McKeown MJ, Boyd LA. Greater activation of secondary motor areas is related to less arm use after stroke. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair. doi: 10.1177/1545968309345269. (In press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyano W, Shibata H, Nakazato K, Haga H, Suyama Y, Matsuzaki T. Prevalence of disability of instrumental activities of daily living among elderly Japanese. Journal of Gerontology. 1988;43:S41–S45. doi: 10.1093/geronj/43.2.s41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang CE, Wagner JM, Edwards DF, Dromerick AW. Upper extremity use in people with hemiparesis in the first few weeks after stroke. Journal of Neurologic Physical Therapy. 2007;31:56–63. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0b013e31806748bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton M, Brody E. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Moss M, Fulcomer M, Kleban MH. A research and service-oriented Multilevel Assessment Instrument. Journal of Gerontology. 1982;37:91–99. doi: 10.1093/geronj/37.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathiowetz V, Weber K, Volland G, Kashman N. Reliability and validity of grip and pinch strength evaluations. Journal of Hand Surgery (American version) 1984;9:222–226. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(84)80146-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathiowetz V, Volland G, Kashman N, Weber K. Adult norms for the Box and Block Test of manual dexterity. American Journal of Occupational therapy. 1985;39:386–391. doi: 10.5014/ajot.39.6.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathiowetz V, Bass-Haugen J. Assessing abilities and capacities: Motor behavior. In: Radomski MV, Trombly-Latham CA, editors. Occupational therapy for physical dysfunction. 6. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. pp. 186–211. [Google Scholar]

- McColl MA, Pollock N. Measuring Occupational Performance Using a Client-Centered Perspective. In: Law M, Baum CM, Dunn WW, editors. Measuring Occupational Performance. Supporting Best Practice in Occupational Therapy. 2. Thorofare, NJ: Slack; 2005. pp. 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 1971;9:97–113. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostwald SK, Snowdon DA, Rysavy DM. Manual dexterity as a correlate of dependency in the elderly. Journal of American Geriatric Society. 1989;37:963–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1989.tb07282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portney LG, Watkins MP. Foundations of clinical research applications to practice. 3. New Jersey: Prentice Hall, Inc; 2009. p. 525. [Google Scholar]

- Rantanen T, Era P, Heikkinen E. Physical activity and the changes in maximal isometric strength in men and women from the age of 75 to 80 years. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 1997;45:1439–1445. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb03193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosamond W, Flegal K, Friday G, Furie K, Go A, Greenlund K, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2007 Update: A report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2007;6(115):69–171. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.179918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki H, Kasagi F, Yamada M, Fujita S. Grip Strength Predicts Cause-Specific Mortality in Middle-Aged and Elderly Persons. American Journal of Medicine. 2007;120:337–342. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solway S, Beaton DE, McConnell S, Bombardier C. The DASH Outcome Measure User’s Manual. 2. Toronto: Institute for Work & Health; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. The Daily. 2007. Retrieved September 16 2008, from www.statcan.ca/Daily/English/070717/d070717a.htm.

- Syddall H, Cooper C, Martin F, Briggs R, Aihie-Sayer A. Is grip strength a useful single marker of frailty? Age and Ageing. 2003;32:650–656. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afg111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taub E. Somatosensory deafferentation research with monkeys: Implications for rehabilitation medicine. In: Ince LP, editor. Behavioral psychology in rehabilitation medicine: Clinical applications. New York: Williams & Wilkins; 1980. pp. 371–401. [Google Scholar]

- Taub E, Uswatte G. Constraint-induced movement therapy: bridging from the primate laboratory to the stroke rehabilitation laboratory. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2003;41:34–40. doi: 10.1080/16501960310010124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uswatte G, Miltner WH, Foo B, Varma M, Moran S, Taub E. Objective measurement of functional upper-extremity movement using accelerometer recordings transformed with a threshold filter. Stroke. 2000;31:662–667. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.3.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uswatte G, Taub E, Morris D, Vignolo M, McCulloch K. Reliability and validity of the upper-extremity Motor Activity Log-14 for measuring real-world arm use. Stroke. 2005;36:2493–2496. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000185928.90848.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uswatte G, Foo WL, Olmstead H, Lopez K, Holand A, Simms LB. Ambulatory monitoring of arm movement using accelerometry: An objective measure of upper-extremity rehabilitation in persons with chronic stroke. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2005;86:1498–1501. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uswatte G, Giuliani C, Winstein C, Zeringue A, Hobbs L, Wolf SL. Validity of accelerometry for monitoring real-world arm activity in patients with subacute stroke: Evidence from the extremity constraint-induced therapy evaluation trial. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2006;87:1340–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Heuvelen MJG, Kempen GIJM, Brouwer WH, de Greef MH. Physical Fitness Related to Disability in Older Persons. Gerontology. 2000;46:333–341. doi: 10.1159/000022187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega-Gonzalez A, Granat MH. Continuous monitoring of upper-limb activity in a free-living environment. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2005;86:541–548. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkek PH, Schouten JP, Oosterhuis HJGH. Measurement of hand coordination. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 1990;92:105–109. doi: 10.1016/0303-8467(90)90084-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams ME, Hadler NM, Earp JA. Manual ability as a marker of dependency in geriatric women. Journal of Chronic Disease. 1982;35:115–122. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(82)90112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winstein CJ, Miller JP, Blanton S, Taub E, Uswatte G, Morris D, Nichols D, Wolf S. Methods for a multisite randomized trial to investigate the effect of constraint-induced movement therapy in improving upper extremity function among adults recovering from a cerebrovascular stroke. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair. 2003;17:137–152. doi: 10.1177/0888439003255511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]