Abstract

Background

Ozone exposure during early life has the potential to contribute to the development of asthma as well as to exacerbate underlying allergic asthma.

Scope of Review

Developmentally regulated aspects of sensitivity to ozone exposure and downstream biochemical and cellular responses.

Major Conclusions

Developmental differences in antioxidant defense responses, respiratory physiology, and vulnerabilities to cellular injury during particular developmental stages all contribute to disparities in the health effects of ozone exposure between children and adults.

General Significance

Ozone exposure has the capacity to affect multiple aspects of the “effector arc” of airway hyperresponsiveness, ranging from initial epithelial damage and neural excitation to neural reprogramming during infancy.

Introduction

The rising prevalence of asthma among populations in industrialized societies has provoked many investigations of the contributions of air pollutants like ozone [1]. Since ozone can provoke both airway hyperreactivity and “prime” epithelial inflammatory responses, [2] it is a likely contributor to the overall burden of asthma. The role of ozone exposure in the initiation of asthma pathophysiology is controversial, but it certainly acts as an exacerbating factor and chronic exposure may have durable effects on susceptibility to airway hyperreactivity. This review will focus on the possible molecular pathways by which early life ozone exposure could affect susceptibility to the development of asthma and asthma exacerbations, as well as its potential interactions with perinatal priming events and co-exposures. The details of ozone interactions in simplified model systems are considered in detail elsewhere in this issue.

Developmental Regulation of Ozone Effects: Anti-Oxidant Responses

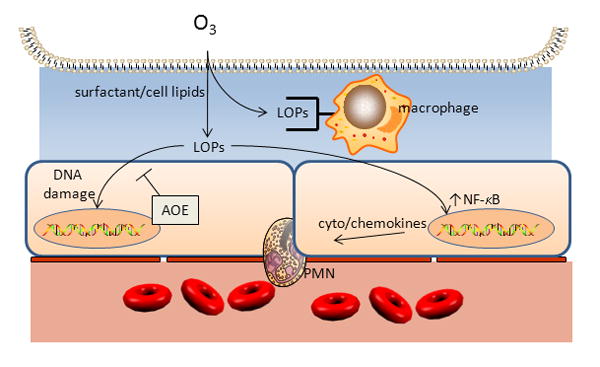

The impact of ozone exposure in the very young will depend on the actual oxidative molecular damage incurred in alveolar and airway epithelium, the initiation and resolution of the consequent inflammatory/injury response, and the consequences of acute or repetitive events during particular windows of developmental plasticity/vulnerability of the entire “effector arc” of airway hyperresponsiveness(AHR). The first events in acute ozone exposure include oxidation of components in airway and alveolar lining fluid. In alveolar lining fluid, ozone reacts with surfactant lipids, producing lipid-ozone reaction products (LOP) which are themselves regulators of transcription factors that govern pro-inflammatory cytokine and chemokine expression, as depicted in Figure 1. These events are reviewed in detail elsewhere in this issue, but it should be pointed out that most studies of acute ozone exposure aimed at disentangling these multiple interacting contributors have been conducted using relatively brief rather than chronic exposures. The actual delivered ozone dose in children is likely to be greater for a given concentration since they have relatively higher minute ventilation and spend more time outdoors. In rats, ozone does not suppress ventilatory response in the 2 week aged juvenile rats as it does in mature animals [3]. However, the relatively greater inducibility of antioxidant enzyme systems, at least in the very young, may partly offset higher oxidative stressor exposure [4] [5]. Two week old juvenile mice exposed to ozone demonstrated less evidence of lung injury than adult counterparts of the same genetic strain [6] and develop less AHR than adult mice [7]. However, the resistance that young mice demonstrate is not necessarily found in other species. In contrast to induction of antioxidant enzymes observed following hyperoxia (see ref# [8] for review), juvenile (postnatal day 21) rats exposed to 0.5 ppm O3 for 12h/day for one week demonstrated no induction of superoxide dismutase, catalase, or glutathione peroxidase activities, although they suffered greater DNA damage assessed as 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro 2′-deoxyguanosine accumulation [9].

Figure 1.

Ozone (O3) reacts with surfactant phospholipids and cellular phospholipids in alveoli to for lipid ozonation products (LOP) that include lipid peroxides, 1-palmitoyl-2-(9′-oxo-nonanoyl)-sn glycero-3-phosphocholine that can stimulate IL-8 release [80], 1-Hydroxy-1-hydroperoxynonane, which activates NF-IL-6 and NF-κB upstream of IL-8 in BEAS-2B cells [81], and others that are capable of inducing local injury and inflammation.

The inducibility of antioxidant defenses in response to oxidative stress in the young has been studied in more detail during the immediate postnatal and neonatal period in a number of species, but much less thoroughly in late infancy and early childhood, the stages of human development during which ozone exposure would be expected to increase. Although recent studies have implicated oxidant/antioxidant gene polymorphisms as ozone susceptibility factors (reviewed by [10]), the developmental regulation of these enzymes has not been studied in detail. Two examples are polymorphisms for glutathione S-transferase mu 1 (GSTM1, EC 2.5.1.18) and NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase (NQO1, E.C. 1.6.99.2). The developmental expression of GSTM1 activity in humans differs depending on the organ, [11] and GST isoforms demonstrate heterogenous expression within the lung [12]. Lack of GSTM1 activity in children in Mexico City was associated with worse ozone-related decrements in pulmonary spirometry that were attenuated in those receiving antioxidant supplementation [13]. NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase (NQO1) has been less well studied, but NQO1 gene polymorphisms appear to confer some protection against acute ozone effects on epithelial injury and AHR [14]. Adult mice lacking NQO1 (Nqo1−/−) are relatively resistant to acute ozone provoked inflammation and AHR [15]. Preliminary data from our laboratory suggests that lack of NQO1 during neonatal ozone exposure also protects against the development of AHR [16]. Further information about age and organ-specific expression and inducibility of these enzyme systems could illuminate the mechanisms underlying developmental vulnerability to ozone exposure.

Ozone exposure & inflammation: infancy→ childhood

Oxidative stress and inflammation interact in response to ozone exposure, and are pivotal to the pathogenesis of asthma. Experimental efforts to estimate the relative contributions of the relevant pathways have employed genetic approaches aimed at candidate pathways. Ozone effects on acute epithelial permeability and on inflammatory responses that follow and affect AHR will hinge on host antioxidant responses and regulation of both initiation and termination of inflammatory responses, both of which are developmentally regulated. The interaction of these pathways to confer susceptibility to short and long-term ozone induced AHR and pulmonary inflammatory has been explored indirectly using inbred adult mouse strains in adult mouse [17], and more recently in newborn mice [6] that demonstrated similar strain-dependence of ozone-induced lung inflammation, with the notable exception that C3HeJ pups—with defective TLR4 signaling—demonstrated greater PMN influx than adults and some other strains. Detailed consideration of ozone exposure and the innate immune system is considered elsewhere in this issue, but even in juvenile mice at postnatal day 4, ozone provoked induction of transcription factors was found to be dependent on TLR4 signaling [18].

Since the mechanistic studies of ozone effects have been conducted in animal models, it is important to take account of the differences in the patterns of pre- and post-natal lung development [19] and specific attributes of lung structure [20] when interpreting the studies. Mice and rats, for example, are born when lungs are at the saccular stage of lung development, whereas macaques and humans are born during the alveolar stage of lung development. Since progenitor cells important to lung homeostasis and repair may also be vulnerable to oxidative stress, ozone exposures at these vulnerable stages may have differing effects on later susceptibility to antigen or pollutant challenge. Inter-species differences in the maturation of immunologic responses are also important to consider when interpreting animal model systems.

In general, ozone exposure induces less lung inflammation in mouse pups (<2 week old) than in adult mice, [21] [7] consistent with generally greater inducibility of anti-oxidant enzymes that oppose formation of lipid-ozone products (LOPs) [22]. These patterns of maturational sensitivity may change with exposures to multiple provocations that are present in the environment.

Despite lower initial inflammatory provocation by acute ozone among neonatal and juvenile animals compared with adults, ozone exposure during early life has been proposed as an agent that can contribute to pulmonary inflammatory responses and the development of asthma [23]. Airborne pollutants have been linked in some epidemiologic studies and experimental studies to skewing of T-lymphocytic responses towards the T-helper 2 (Th2) pattern associated with allergic asthma [24]. However there are no direct experimental studies that link ozone exposure with initial ‘polarization’ of Th1 → Th2 lymphocytic responses. On the other hand, natural killer T cells appear to be required for semi-acute (5d) ozone-induced AHR in adult mice.

An important aspect of ozone-induced AHR in the context of childhood asthma is the apparent interaction with antigen sensitization. Macaques exposed to ozone and house dust mite antigen during infancy demonstrated increased abundance of activated T-lymphocytes (CD8+/CD25+) in the airway mucosa, with ozone exposure shifting the increased abundance towards more proximal airways [25]. These effects do not appear to be correlated with large changes in resident mast cell populations in macaque airways [26], since antigen exposure increased mast cell abundance, while the addition of ozone exposure to antigen exposure attenuated this response.

In most model systems, ozone seems to serve as an adjuvant, increasing the phenotypic lung mechanical and inflammatory responses during antigen challenge, rather than during antigen presentation [10]. The interactions between ozone-provoked inflammatory responses and subsequent development of asthma phenotypes are complex, and likely depend on highly individualized host responses. Children that have diminished ability to be sensitized, for example those with diminished IgE responses—e.g., Fc εR1 functional polymorphisms—have less frequent wheezing with ozone exposure [27]. Most the information linking ozone exposure with early childhood sensitization in the context of childhood asthma is based on very limited computational estimations of exposure [28].

Oxidative stress interaction with nitric oxide (NO) metabolism and childhood asthma

The mechanisms by which ozone could affect the risk for childhood asthma must also include interactions with NO signaling. Regulation of oxidative stress in the context of ozone exposure may have effects through interaction of ROS with endogenous NO. NO and its reaction products (e.g., S-nitrosothiols) are required for airway smooth muscle relaxation (see review by Erzurum in this issue) and reduced degradation of S-nitrosogluathione ablates AHR in allergen challenged mice [29]. Endogenous NO appears to be linked to multiple mechanisms in asthma pathogenesis, but understanding its contributions has been plagued by inconsistent results in animal model systems [30]. The role of NO in asthma pathogenesis associated with ozone exposure in children will likely depend on the developmental differences in physiology and antioxidant defenses discussed above. There are fewer published studies linking exhaled airway NO (eNO) concentrations with disease states in children than in adults, but in general disease states dominated by impaired epithelial function—e.g., primary ciliary dyskinesia [31]—will exhibit low eNO while inflammation such as asthma exacerbations typically exhibit higher levels [32].

Nevertheless, interest in the interaction of NO and asthma pathophysiology in children remains strong because of a number of NO metabolism gene association studies. For example, children who lack GSTM1 (GSTM1 −/−) and possess inducible NO synthase (NOS2A promoter region) polymorphisms are at higher risk to develop asthma [33]. NO production and NOS activity depend on arginine metabolism by arginase [34], and decreased arginine bioavailability, as well as increased arginase activity in serum is associated with asthma [35]. The association of altered arginase activity with asthma risk is also suggested by the prevalence of arginase gene polymorphisms for ARG1 and ARG2 with childhood asthma, which appears to be enhanced by ozone exposure [36]. To date, these gene polymorphism studies represent only associations, since functional studies on human gene transcription/translation have not yet been published. Direct inhibition of arginase in murine allergic asthma models reduces AHR and airway inflammation [37], as does L-arginine supplementation [38].

Ozone and childhood asthma: never alone

Airborne pollutant exposures during childhood are predominantly to mixtures. For example, gas-phase co-pollutants can exert their own direct effects on the respiratory tract; however, they may also enhance the deposition fraction for solid-phase air pollutants (fine and coarse particles) and localize and intensify injury to epithelial surfaces [39]. Short term effects of particulate and photochemical air pollution in asthmatic children from representative urban city centers in Europe and North America have been associated with several health outcomes, including asthma attacks, symptoms of nocturnal cough, and changes in lung function [40–45]. In addition, other air quality criteria pollutants, such as carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, and sulfur dioxide have also been linked to asthma aggravation [46–48].

Long-standing efforts to disentangle the relative contributions of individual pollutant species are inevitably fraught with the challenges of balancing the high relevance and low precision of epidemiologic studies with the converse trade off in experimental human and animal studies. The severity (dose), chronicity, and developmental window of vulnerability to ozone exposure, as well as the nature of co-exposures in experimental models will produce differing phenotypes, some of which are summarized in Table 1. The addition of mixed or sequential pollutant exposure to experimental models has become commonplace for in vitro studies and acute adult exposures, but has not been as fully developed in the study of the role of ozone and other co-exposures or pre-natal exposures on the development of asthma. Furthermore, most animal experiments have relied on components of air pollutants as surrogates, since they have been designed as classical toxicologic studies.

Table 1.

List comparing results from ozone exposures in selected studies in newborn/juvenile animals.

| Reference # | year | species | age | exposure regimen | duration | finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [69] | 1978 | rat | P20 | 0.85 ppm × 3d | acute | minimal morphologic change at terminal airways |

| [71] | 1986 | dog | 6 wk | 1–2 ppm, 4h/d × 5d | semi-acute | small effects on alveolar development |

| [72] | 1986 | sheep | 2 wk | 1 ppm, 4h/day × 5d | semi-acute | delayed involution of mucus cells in trachea |

| [3] | 2000 | rat | 2–12 wk | 2 ppm × 4h | acute | O3 reduces ventilation: young<mature |

| [7] | 2004 | mouse | 2–12 wk | 0.3–3.0 ppm × 3h | acute | O3 induces AHR: young<mature |

| [56] | 2004 | macaque | infant | 0.5 ppm × 8h × 5d × 11 cycles | chronic | remodeled neural comp of EMTU |

| [21] | 2004 | mouse | P2–P56 | 2 ppm × 4h | acute | varied responses |

| [49] | 2006 | mouse | P4 | 2.5 × 4h | acute | O3 induction of c-jun/c-fos TLR4- dependent |

| [56] | 2006 | macaque | infant | 0.5 ppm × 8h × 5d × 11 cycles | chronic | abnormal airway structure |

| [57] | 2007 | macaque | infant | “ “ “ “ “ | chronic | O3±allergen→↑airway sensory nn. |

| [25] | 2009 | macaque | infant | “ “ “ “ “ | chronic | CD25 cells airway prevalence altered |

| [51] | 2009 | mouse | neonatal P1–P28 | 1 ppm 4h/d, 3d/wk × 4 | chronic | maternal PM ‘primes’ neonatal O3-induced AHR |

| [55] | 2010 | rat | neonatal v. juvenile | “prime” at P2–6 v. P19– 23 + re-challenge P28 | acute | neonatal exposure→↑airway sensory nn. |

| [26] | 2010 | macaque | infant | 0.5 ppm × 8h × 5d × 11 cycles | chronic | O3 blocked allergen→↑ tracheal mast cells |

As experimental studies have become more sophisticated, threshold effects and synergies have become apparent that were previously unappreciated. For example, the “resistance” of young animals to acute ozone effects on lung inflammation disappears when it follows a priming event such as LPS exposure. The converse was also shown, with ozone serving to augment sensitivity to LPS in newborn mice [49]. Priming events that enhance susceptibility to later environmental challenges may also take place antenatally, such as maternal pulmonary exposure to air pollutants. Fedulov and colleagues found that diesel particles or carbon black instillation in pregnant mice could lower the threshold for ovalbumin sensitization in offspring [50]. Using a similar approach, we found that tracheal instillation of an industrial particulate matter (NIST SRM#1648) to pregnant mice induced inflammatory cytokines in placenta and lung in the fetus, and augmented chronic ozone induced AHR in offspring [51]. Most of the epidemiologic studies linking ozone exposure with childhood asthma have focused on exacerbations or acute effects [1]. However, recent cross-sectional studies suggest that chronic ozone exposure is associated with the development of childhood asthma [52], which has prompted the revision of experimental models accordingly. Recent preliminary studies in our laboratory confirm that maternal exposure to inhaled fresh diesel exhaust [53] worsens chronic ozone exposure induced AHR in offspring.

Ozone Exposure Effects in Early Life: Neural Plasticity

Much of the recent experimental and investigational emphasis has been on the immunologic responses that undergird allergic asthma. However, the “effector arc” for ozone-induced airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) involves airway sensory nerve responses, possibly via transient receptor potential channels [54]. In newborn rats, early ozone exposure (postnatal days 2–6) but not late exposure (days 19–23) increased airway sensory nerves, suggesting a particular window of neural developmental plasticity [55]. Furthermore, the early exposure increased susceptibility to re-exposure induced AHR during adulthood. Chronic intermittent ozone exposure in early life in animal models increased the abundance of airway sensory nerves in Rhesus monkeys, as well as potentiating the effect of chronic allergen exposure on nerve distribution [56] [57]. Early effects on innervation could thus increase susceptibility to later ozone exposure or to other airway irritants.

Although the majority of studies on the contribution of ozone to neuronal development have been on airway afferent innervation, it should be understood that the central nervous system also plays a role in asthma exacerbations in humans [58] and may contribute to asthma ontogeny. Rats born to dams exposed to chronic ozone administration during pregnancy exhibited neurobehavioral changes, [59] as well as abnormalities of neurotransmitter precursors in the brain measured at birth or during the first postnatal week [60]. Recent studies suggest that prenatal ozone exposure has long-lasting effects on central nervous system plasticity [61]. Rhesus monkeys exposed to chronic ozone during infancy exhibited decreased responsiveness of neurons in the nucleus tractus solitarius [62]. Surprisingly, the effects of postnatal ozone exposure on central nervous system structure and function have not been studied in detail.

The potential effects of ozone on behavior during critical periods must be considered when interpreting both animal and human studies of ozone effects during development. Studies that separate rodent dams from suckling pups have significant effects on the hypothalamic-pituitary axis that could potentially confound airway immunologic interactions important to ozone exposure effects [63]. Indirect effects could also include impairment of postnatal weight gain or decreased maternal-pup transfer of immunologic mediators via suckling [64, 65]. In human studies of chronic ozone exposure among children it is important to consider the indirect effects as well. Human maternal depression, linked with childhood asthma susceptibility in offspring [66], is also influenced by impoverished residential conditions [67] more likely to have proximity to air pollutant-rich environments such as roadways.

Ozone exposure during infancy and structural changes in the lung

Because of the obvious immediate effects of ozone exposure on respiratory function, and the association with asthma exacerbations, chronic ozone exposure would be expected to adversely affect lung structural development. Ozone exposure has been linked with decrements in lung function in children [68], but the pathophysiology in this age group has not been studied in detail.

To address the gap in knowledge about developmental effects, many of the studies in recent years have used rodents as experimental models (Table 1). There are inherent advantages and liabilities of altricial species such as mice as suitable models of human asthma that have been reviewed in detail [69, 70]. Mice exposed to chronic intermittent ozone beginning at birth for 1 month did not have significant changes in airway or alveolar structure despite demonstrating increased AHR in response to nebulized methacholine [51], but in our preliminary studies were shown to exhibit long-term AHR at age 8 weeks [53]. Rats exposed as juveniles, near weaning, at postnatal day 20, to acute ozone do not demonstrate significant structural changes [71].

Studies of neonatal and juvenile ozone exposure in precocial species with more extensive alveolar development are more limited. It should be emphasized that the interpretation of the physiological observations in animal studies must be informed by a thorough understanding of the species-related interrelations between structure and function [72]. As with rodents, puppies (6 weeks) [73] and lambs (2 weeks) [74] exposed to < 2 ppm ozone for 5 days do not develop significant structural changes.

A series of detailed morphological analyses using Rhesus macaques exposed during the first six months of life to chronic ozone have revealed a complex of relatively subtle changes that, taken together, could contribute to AHR (see ref# [57] for review). The significant advantages as well as the limitations of non-human primate models are reviewed elsewhere [75]. We have summarized some of the findings in this model system in Table 1. As in the mouse studies, chronic ozone exposure during infancy produced little evidence of airway smooth muscle hypertrophy, and only modest changes in airway muscle fiber arrangement unless macaques were also exposed to house dust mite antigen. As with the majority of chronic experimental exposure studies, ozone exposure of infant macaques at environmentally relevant ozone concentrations augmented the antigen exposure-induced structural changes that contributed to experimental asthma [76].

Ozone exposure during early life and airway homeostasis/repair

Oxidative stress in the late saccular to alveolar stages of lung development can have significant effects on alveolar development and repair responses in adults that could contribute to airway stability. Relatively brief exposures to hyperoxia (postnatal days 1–4) impair alveolar development in adult mice and increase their vulnerability to influenza-induced pneumonitis [77]. This susceptibility has been suggested to depend on loss of alveolar repair capacity, possibly through effects on alveolar progenitor cells. The source of these cells has not been identified but does not appear to include terminal bronchiolar epithelium [78]. Recent studies suggest that airway epithelial progenitor cell populations in adult mice exhibit different proliferation capacities depending on the insult (ozone, SO2, naphthalene) [79]. Whether ozone exposure can also have effects on long-term repair capacity in the airway or alveoli is unclear.

Summary

Ozone exposure during postnatal development may serve as a priming event that enhances the toxicity of other pollutants or allergens. Its impact likely hinges on the local antioxidant defenses, which vary depending on age, and which may be modifiable with antioxidant supplementation. Ozone effects on innate and adaptive immunologic pathways relevant to asthma have been observed in animal models, but the relevance to human asthma is not yet clear. The best evidence from non-human primates suggests that eventual development of asthma in children may also be attributable in part to remodeling of afferent airway nerves and subtle effects on airway structure and function. These changes may have implications for life-long vulnerability to other oxidative and allergic challenges that produce clinical asthma.

Acknowledgments

RLA and WMF were supported by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Children’s Environmental Health Center award RD 833293-01, and WMF was supported by NIH AI 081672.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lee JT, Cho YS, Son JY. Relationship between ambient ozone concentrations and daily hospital admissions for childhood asthma/atopic dermatitis in two cities of Korea during 2004–2005. Int J Environ Health Res. 2010;20:1–11. doi: 10.1080/09603120903254033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hollingsworth JW, Kleeberger SR, Foster WM. Ozone and pulmonary innate immunity. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4:240–246. doi: 10.1513/pats.200701-023AW. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shore SA, Abraham JH, Schwartzman IN, Murthy GG, Laporte JD. Ventilatory responses to ozone are reduced in immature rats. J Appl Physiol. 2000;88:2023–2030. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.6.2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frank L, Bucher JR, Roberts RJ. Oxygen toxicity in neonatal and adult animals of various species. J Appl Physiol. 1978;45:699–704. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1978.45.5.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoffman M, Stevens JB, Autor AP. Adaptation to hyperoxia in the neonatal rat: kinetic parameters of the oxygen-mediated induction of lung superoxide dismutases, catalase and glutathione peroxidase. Toxicology. 1980;16:215–225. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(80)90118-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vancza EM, Galdanes K, Gunnison A, Hatch G, Gordon T. Age, strain, and gender as factors for increased sensitivity of the mouse lung to inhaled ozone. Toxicol Sci. 2009;107:535–543. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shore SA, Johnston RA, Schwartzman IN, Chism D, Krishna Murthy GG. Ozone-induced airway hyperresponsiveness is reduced in immature mice. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92:1019–1028. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00381.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Auten RL, Davis JM. Oxygen toxicity and reactive oxygen species: the devil is in the details. Pediatr Res. 2009;66:121–127. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181a9eafb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Servais S, Boussouar A, Molnar A, Douki T, Pequignot JM, Favier R. Age-related sensitivity to lung oxidative stress during ozone exposure. Free Radic Res. 2005;39:305–316. doi: 10.1080/10715760400011098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Backus-Hazzard GS, Howden R, Kleeberger SR. Genetic susceptibility to ozone-induced lung inflammation in animal models of asthma. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;4:349–353. doi: 10.1097/00130832-200410000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCarver DG, Hines RN. The ontogeny of human drug-metabolizing enzymes: phase II conjugation enzymes and regulatory mechanisms. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;300:361–366. doi: 10.1124/jpet.300.2.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anttila S, Hirvonen A, Vainio H, Husgafvel-Pursiainen K, Hayes JD, Ketterer B. Immunohistochemical localization of glutathione S-transferases in human lung. Cancer Res. 1993;53:5643–5648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Romieu I, Sienra-Monge JJ, Ramirez-Aguilar M, Moreno-Macias H, Reyes-Ruiz NI, Estela del Rio-Navarro B, Hernandez-Avila M, London SJ. Genetic polymorphism of GSTM1 and antioxidant supplementation influence lung function in relation to ozone exposure in asthmatic children in Mexico City. Thorax. 2004;59:8–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bergamaschi E, De Palma G, Mozzoni P, Vanni S, Vettori MV, Broeckaert F, Bernard A, Mutti A. Polymorphism of quinone-metabolizing enzymes and susceptibility to ozone-induced acute effects. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1426–1431. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.6.2006056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Voynow JA, Fischer BM, Zheng S, Potts EN, Grover AR, Jaiswal AK, Ghio AJ, Foster WM. NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase 1 is essential for ozone-induced oxidative stress in mice and humans. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;41:107–113. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0381OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 16.Potts EN, Auten RL, Mason SN, Foster WM. Pulmonary susceptibility of neonatal mize to ozone modulated by Nqo1. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009 Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Savov JD, Whitehead GS, Wang J, Liao G, Usuka J, Peltz G, Foster WM, Schwartz DA. Ozone-induced acute pulmonary injury in inbred mouse strains. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;31:69–77. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0001OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnston CJ, Holm BA, Gelein R, Finkelstein JN. Postnatal lung development: immediate-early gene responses post ozone and LPS exposure. Inhal Toxicol. 2006;18:875–883. doi: 10.1080/08958370600822466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zoetis T, Hurtt ME. Species comparison of lung development. Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol. 2003;68:121–124. doi: 10.1002/bdrb.10014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rock JR, Randell SH, Hogan BL. Airway basal stem cells: a perspective on their roles in epithelial homeostasis and remodeling. Dis Model Mech. 2010;3:545–556. doi: 10.1242/dmm.006031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnston CJ, Holm BA, Finkelstein JN. Differential proinflammatory cytokine responses of the lung to ozone and lipopolysaccharide exposure during postnatal development. Exp Lung Res. 2004;30:599–614. doi: 10.1080/01902140490476355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rahman I, Adcock IM. Oxidative stress and redox regulation of lung inflammation in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:219–242. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00053805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steerenberg PA, Garssen J, van Bree L, van Loveren H. Ozone alters T-helper cell mediated bronchial hyperreactivity and resistance to bacterial infection. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 1996;48:497–499. doi: 10.1016/S0940-2993(96)80065-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang TN, Chiang W, Tseng HI, Chu YT, Chen WY, Shih NH, Ko YC. The polymorphisms of Eotaxin 1 and CCR3 genes influence on serum IgE, Eotaxin levels and mild asthmatic children in Taiwan. Allergy. 2007;62:1125–1130. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller LA, Gerriets JE, Tyler NK, Abel K, Schelegle ES, Plopper CG, Hyde DM. Ozone and allergen exposure during postnatal development alters the frequency and airway distribution of CD25+ cells in infant rhesus monkeys. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2009;236:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.12.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Winkle LS, Baker GL, Chan JK, Schelegle ES, Plopper CG. Airway mast cells in a rhesus model of childhood allergic airways disease. Toxicol Sci. 2010;116:313–322. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee YL, Gilliland FD, Wang JY, Lee YC, Guo YL. Associations of FcepsilonRIbeta E237G polymorphism with wheezing in Taiwanese school children. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38:413–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Selgrade MK, Plopper CG, Gilmour MI, Conolly RB, Foos BS. Assessing the health effects and risks associated with children’s inhalation exposures--asthma and allergy. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2008;71:196–207. doi: 10.1080/15287390701597897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Que LG, Liu L, Yan Y, Whitehead GS, Gavett SH, Schwartz DA, Stamler JS. Protection from experimental asthma by an endogenous bronchodilator. Science. 2005;308:1618–1621. doi: 10.1126/science.1108228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathrani VC, Kenyon NJ, Zeki A, Last JA. Mouse models of asthma: can they give us mechanistic insights into the role of nitric oxide? Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:2204–2213. doi: 10.2174/092986707781389628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shoemark A, Wilson R. Bronchial and peripheral airway nitric oxide in primary ciliary dyskinesia and bronchiectasis. Respir Med. 2009;103:700–706. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gabriele C, de Benedictis FM, de Jongste JC. Exhaled nitric oxide measurements in the first 2 years of life: methodological issues, clinical and epidemiological applications. Ital J Pediatr. 2009;35:21. doi: 10.1186/1824-7288-35-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Islam T, Breton C, Salam MT, McConnell R, Wenten M, Gauderman WJ, Conti D, Van Den Berg D, Peters JM, Gilliland FD. Role of inducible nitric oxide synthase in asthma risk and lung function growth during adolescence. Thorax. 2010;65:139–145. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.114355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maarsingh H, Zaagsma J, Meurs H. Arginase: a key enzyme in the pathophysiology of allergic asthma opening novel therapeutic perspectives. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158:652–664. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00374.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morris CR, Poljakovic M, Lavrisha L, Machado L, Kuypers FA, Morris SM., Jr Decreased arginine bioavailability and increased serum arginase activity in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:148–153. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200309-1304OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salam MT, Islam T, Gauderman WJ, Gilliland FD. Roles of arginase variants, atopy, and ozone in childhood asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:596–602. 602, e591–598. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takahashi N, Ogino K, Takemoto K, Hamanishi S, Wang DH, Takigawa T, Shibamori M, Ishiyama H, Fujikura Y. Direct inhibition of arginase attenuated airway allergic reactions and inflammation in a Dermatophagoides farinae-induced NC/Nga mouse model. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2010;299:L17–24. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00216.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mabalirajan U, Ahmad T, Leishangthem GD, Joseph DA, Dinda AK, Agrawal A, Ghosh B. Beneficial effects of high dose of L-arginine on airway hyperresponsiveness and airway inflammation in a murine model of asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:626–635. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Foster WM, Silver JA, Groth ML. Exposure to ozone alters regional function and particle dosimetry in the human lung. J Appl Physiol. 1993;75:1938–1945. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.5.1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Just J, Segala C, Sahraoui F, Priol G, Grimfeld A, Neukirch F. Short-term health effects of particulate and photochemical air pollution in asthmatic children. Eur Respir J. 2002;20:899–906. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00236902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Villeneuve PJ, Chen L, Rowe BH, Coates F. Outdoor air pollution and emergency department visits for asthma among children and adults: a case-crossover study in northern Alberta, Canada. Environ Health. 2007;6:40. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-6-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Delfino RJ, Zeiger RS, Seltzer JM, Street DH. Symptoms in pediatric asthmatics and air pollution: differences in effects by symptom severity, anti-inflammatory medication use and particulate averaging time. Environ Health Perspect. 1998;106:751–761. doi: 10.1289/ehp.98106751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Margolis HG, Mann JK, Lurmann FW, Mortimer KM, Balmes JR, Hammond SK, Tager IB. Altered pulmonary function in children with asthma associated with highway traffic near residence. Int J Environ Health Res. 2009;19:139–155. doi: 10.1080/09603120802415792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peters A, Goldstein IF, Beyer U, Franke K, Heinrich J, Dockery DW, Spengler JD, Wichmann HE. Acute health effects of exposure to high levels of air pollution in eastern Europe. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;144:570–581. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Romieu I, Meneses F, Ruiz S, Huerta J, Sienra JJ, White M, Etzel R, Hernandez M. Effects of intermittent ozone exposure on peak expiratory flow and respiratory symptoms among asthmatic children in Mexico City. Arch Environ Health. 1997;52:368–376. doi: 10.1080/00039899709602213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Slaughter JC, Lumley T, Sheppard L, Koenig JQ, Shapiro GG. Effects of ambient air pollution on symptom severity and medication use in children with asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;91:346–353. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61681-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Timonen KL, Pekkanen J. Air pollution and respiratory health among children with asthmatic or cough symptoms. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:546–552. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.2.9608044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu O, Sheppard L, Lumley T, Koenig JQ, Shapiro GG. Effects of ambient air pollution on symptoms of asthma in Seattle-area children enrolled in the CAMP study. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108:1209–1214. doi: 10.1289/ehp.001081209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johnston CJ, Holm BA, Finkelstein JN. Sequential exposures to ozone and lipopolysaccharide in postnatal lung enhance or inhibit cytokine responses. Exp Lung Res. 2005;31:431–447. doi: 10.1080/01902140590918605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fedulov AV, Leme A, Yang Z, Dahl M, Lim R, Mariani TJ, Kobzik L. Pulmonary exposure to particles during pregnancy causes increased neonatal asthma susceptibility. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;38:57–67. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0124OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Auten RL, Potts EN, Mason SN, Fischer BM, Huang Y, Foster MW. Maternal Exposure to Particulate Matter Increases Postnatal Ozone-Induced Airway Hyperresponsiveness in Juvenile Mice. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2009 doi: 10.1164/rccm.200901-0116OC. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 52.Akinbami LJ, Lynch CD, Parker JD, Woodruff TJ. The association between childhood asthma prevalence and monitored air pollutants in metropolitan areas, United States, 2001–2004. Environ Res. 2010;110:294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Auten RL, Mason SN, Gilmour MI, Foster WM. EPAS 2009. Baltimore, MD: 2009. Maternal diesel exhaust particle inhalation worsens postnatal ozone induced airway hyperreactivity in mice (abstract) p. 3858.3133. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Taylor-Clark TE, Undem BJ. Ozone activates airway nerves via the selective stimulation of TRPA1 ion channels. J Physiol. 588:423–433. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.183301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hunter DD, Wu Z, Dey RD. Sensory neural responses to ozone exposure during early postnatal development in rat airways. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010;43:750–757. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0191OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Larson SD, Schelegle ES, Walby WF, Gershwin LJ, Fanuccihi MV, Evans MJ, Joad JP, Tarkington BK, Hyde DM, Plopper CG. Postnatal remodeling of the neural components of the epithelial-mesenchymal trophic unit in the proximal airways of infant rhesus monkeys exposed to ozone and allergen. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2004;194:211–220. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2003.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kajekar R, Pieczarka EM, Smiley-Jewell SM, Schelegle ES, Fanucchi MV, Plopper CG. Early postnatal exposure to allergen and ozone leads to hyperinnervation of the pulmonary epithelium. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2007;155:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rosenkranz MA, Busse WW, Johnstone T, Swenson CA, Crisafi GM, Jackson MM, Bosch JA, Sheridan JF, Davidson RJ. Neural circuitry underlying the interaction between emotion and asthma symptom exacerbation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13319–13324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504365102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sorace A, de Acetis L, Alleva E, Santucci D. Prolonged exposure to low doses of ozone: short- and long-term changes in behavioral performance in mice. Environ Res. 2001;85:122–134. doi: 10.1006/enrs.2000.4097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gonzalez-Pina R, Escalante-Membrillo C, Alfaro-Rodriguez A, Gonzalez-Maciel A. Prenatal exposure to ozone disrupts cerebellar monoamine contents in newborn rats. Neurochem Res. 2008;33:912–918. doi: 10.1007/s11064-007-9534-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boussouar A, Araneda S, Hamelin C, Soulage C, Kitahama K, Dalmaz Y. Prenatal ozone exposure abolishes stress activation of Fos and tyrosine hydroxylase in the nucleus tractus solitarius of adult rat. Neurosci Lett. 2009;452:75–78. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen CY, Bonham AC, Plopper CG, Joad JP. Neuroplasticity in nucleus tractus solitarius neurons after episodic ozone exposure in infant primates. J Appl Physiol. 2003;94:819–827. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00552.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vig R, Gordon JR, Thebaud B, Befus AD, Vliagoftis H. The effect of early-life stress on airway inflammation in adult mice. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2010;17:229–239. doi: 10.1159/000290039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Polte T, Hansen G. Maternal tolerance achieved during pregnancy is transferred to the offspring via breast milk and persistently protects the offspring from allergic asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38:1950–1958. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Verhasselt V, Milcent V, Cazareth J, Kanda A, Fleury S, Dombrowicz D, Glaichenhaus N, Julia V. Breast milk-mediated transfer of an antigen induces tolerance and protection from allergic asthma. Nat Med. 2008;14:170–175. doi: 10.1038/nm1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Klinnert MD, Nelson HS, Price MR, Adinoff AD, Leung DY, Mrazek DA. Onset and persistence of childhood asthma: predictors from infancy. Pediatrics. 2001;108:E69. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.4.e69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Siefert K, Finlayson TL, Williams DR, Delva J, Ismail AI. Modifiable risk and protective factors for depressive symptoms in low-income African American mothers. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2007;77:113–123. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Romieu I, Sienra-Monge JJ, Ramirez-Aguilar M, Tellez-Rojo MM, Moreno-Macias H, Reyes-Ruiz NI, del Rio-Navarro BE, Ruiz-Navarro MX, Hatch G, Slade R, Hernandez-Avila M. Antioxidant supplementation and lung functions among children with asthma exposed to high levels of air pollutants. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:703–709. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2112074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shapiro SD. Animal models of asthma: Pro: Allergic avoidance of animal (model[s]) is not an option. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:1171–1173. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2609001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wenzel S, Holgate ST. The mouse trap: It still yields few answers in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:1173–1176. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2609002. discussion 1176–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stephens RJ, Sloan MF, Groth DG, Negi DS, Lunan KD. Cytologic responses of postnatal rat lungs to O3 or NO2 exposure. Am J Pathol. 1978;93:183–200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bates JH, Rincon M, Irvin CG. Animal Models of Asthma. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009 doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00027.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Phalen RF, Crocker TT, McClure TR, Tyler NK. Effect of ozone on mean linear intercept in the lung of young beagles. J Toxicol Environ Health. 1986;17:285–296. doi: 10.1080/15287398609530823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Abraham WM, Sielczak MW, Delehunt JC, Marchette B, Wanner A. Impairment of tracheal mucociliary clearance but not ciliary beat frequency by a combination of low level ozone and sulfur dioxide in sheep. Eur J Respir Dis. 1986;68:114–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Plopper CG, Hyde DM. The non-human primate as a model for studying COPD and asthma. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2008;21:755–766. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fanucchi MV, Plopper CG, Evans MJ, Hyde DM, Van Winkle LS, Gershwin LJ, Schelegle ES. Cyclic exposure to ozone alters distal airway development in infant rhesus monkeys. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291:L644–650. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00027.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.O’Reilly MA, Marr SH, Yee M, McGrath-Morrow SA, Lawrence BP. Neonatal hyperoxia enhances the inflammatory response in adult mice infected with influenza A virus. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:1103–1110. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200712-1839OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rawlins EL, Okubo T, Xue Y, Brass DM, Auten RL, Hasegawa H, Wang F, Hogan BL. The role of Scgb1a1+ Clara cells in the long-term maintenance and repair of lung airway, but not alveolar, epithelium. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:525–534. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Teisanu RM, Chen H, Matsumoto K, McQualter JL, Potts E, Foster WM, Bertoncello I, Stripp BR. Functional Analysis of Two Distinct Bronchiolar Progenitors during Lung Injury and Repair. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010 doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0098OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Uhlson C, Harrison K, Allen CB, Ahmad S, White CW, Murphy RC. Oxidized phospholipids derived from ozone-treated lung surfactant extract reduce macrophage and epithelial cell viability. Chem Res Toxicol. 2002;15:896–906. doi: 10.1021/tx010183i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kafoury RM, Hernandez JM, Lasky JA, Toscano WA, Jr, Friedman M. Activation of transcription factor IL-6 (NF-IL-6) and nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-kappaB) by lipid ozonation products is crucial to interleukin-8 gene expression in human airway epithelial cells. Environ Toxicol. 2007;22:159–168. doi: 10.1002/tox.20246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]