Abstract

Objective

Physiotherapies are the most widely recommended conservative treatment options for arthritic diseases. Here we examined the molecular mechanisms underlying the effects of gentle treadmill walking (GTW) on various stages of monoiodoacetate-induced arthritis (MIA) to unravel the basis for the success or failure of such therapies on the damaged joints.

Methods

Rat knees were harvested from untreated control, MIA afflicted but not subjected to GTW, GTW regimens started one day post-MIA induction, or after cartilage damage had progressed to Grade 1 or Grade 2. The cartilage was examined by macroscopic, microscopic, μCT imaging and transcriptome-wide gene expression analysis. Microarray data was analyzed by Ingenuity Pathways Analysis to construct molecular functional networks regulated by GTW.

Results

GTW intervention started on day 1 post-MIA induction significantly prevented the MIA progression, but its efficacy was reduced when implemented on the knees exhibiting close to Grade 1 cartilage damage. However, GTW accelerated damage in the knees with close to Grade 2 cartilage pathologies. Transcriptome-wide gene expression analysis revealed that GTW intervention started one day post-MIA inception significantly suppressed inflammation-associated genes and upregulated matrix associated gene networks. However, delayed GTW intervention following Grade 1 damage was less effective in suppressing proinflammatory genes or upregulating matrix synthesis.

Conclusion

The findings suggest that GTW suppresses proinflammatory gene networks and upregulates matrix synthesis to prevent progression of cartilage damage in MIA afflicted knees. However, the extent of cartilage damage at the initiation of GTW may be an important determinant for the success or failure of such therapies.

Exercise is the most widely recommended and used conservative therapeutic approach to improve joint function in arthritis (1–3). Recent guidelines published by Osteoarthritis Research Society International suggest that exercise is in general beneficial for patients with osteoarthritis (OA) (3). Such recommendations are supported by large cohort studies demonstrating that adults engaging in minimal to no physical activity show higher incidence of radiographically diagnosed osteoarthritis (4). Additionally, older adults engaged in moderate physical activity show reduced risk of arthritis-related disability (5). However, in some patients physical activity is either associated with a greater risk or has no effect on knee joints, making it difficult to discern which patients will or will not benefit from physical therapies (6–9).

Chondrocytes, mechanoresponsive cells within the cartilage, perceive and respond to mechanical stimuli by altering their biosynthetic ability, morphology and cartilage extracellular matrix (10, 11). These cells interpret mechanical signals in a magnitude dependent manner (12, 13). Excessive loading of joints is injurious and activates proinflammatory signaling cascades, similar to those implicated in the etiology of OA (14–17). Contrarily, physiological loading is shown to be antiinflammatory and induce IL-10 production in the synovium, and upregulate synthesis of glycosaminoglycans in the cartilage of patients at increased risk of OA (18–21). In fact, exercise is vital for cartilage homeostasis and its lack atrophies cartilage (22), implicating distinct roles of physiotherapies in both preventing damage and improving joint function.

The aim of this study was to determine the molecular mechanisms underlying the effectiveness of exercise in the form of gentle treadmill walking (GTW) on well-defined stages of cartilage damage, using a rat knee model of MIA (23). Others and we have shown earlier that low or physiological levels of compressive/tensile forces are antiinflammatory on chondrocytes in vitro. These forces suppress several biomarkers of inflammation, such as IL-1β, TNF-α, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and aggrecanases (12, 13, 24, 25). Here, we systematically examined the efficacy of moderate exercise on the progression of MIA macroscopically, microscopically, and by microtomographic (μCT) imaging. A transcriptome-wide microarray analysis was also conducted to track the changes in gene expression subsequent to GTW therapy to gain key insights into the basis of success or failure of such therapies (1, 3, 4, 26).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Induction of experimental knee MIA and GTW regimens

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at The Ohio State University approved all protocols. A well-established model of MIA in rat knees was used, which exhibited similar pathologies as described by Guzman et al (23). Typically, monoiodoacetate-administered knees exhibited close to Grade 1 cartilage damage on the condylar surface on day 5, close to Grade 2 on condyles by day 9, and close to Grade 3 to 3.5 cartilage and bone damage on day 21 (23).

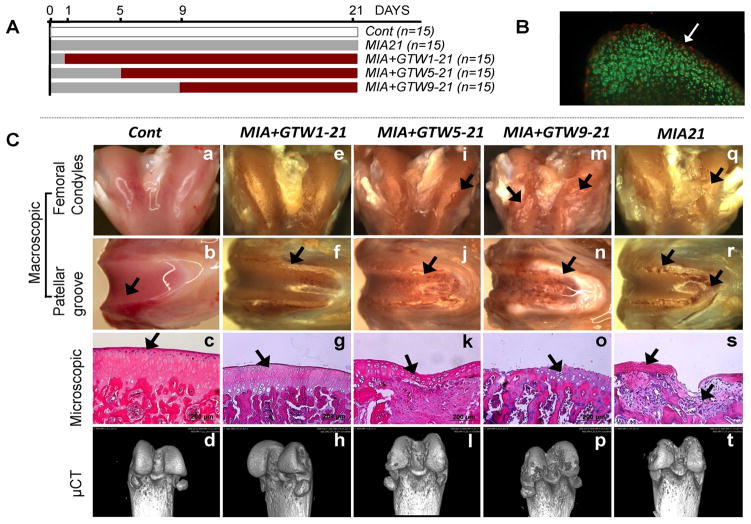

MIA was induced in the right knees of 12–14 weeks old female Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan, IN) via single intraarticular injection of monoiodoacetate (2 mg/50μl saline/knee) (23). Sham controls (Cont) were injected with 50μl saline in the right knees of separate rats. The rats were subjected to GTW on a small animal treadmill (Columbus Instruments, OH) at a speed of 12 meters/minute for 45 minutes/day (roughly 0.5 kilometer). This regimen was based on earlier studies, but was gentler to avoid pain and resistance to walking due to MIA (27). The MIA afflicted rats showed no signs of limping, pain or resistance during GTW. One day post-MIA induction, the pH of the synovial fluid was between 7.5–8.5, suggesting likely dissemination of monoiodoacetate from joints, prior to start of GTW regimens. GTW regimens were started on day 1 (no apparent cartilage damage and less than 2% cell death observed on the surface of cartilage; Live/dead cell kit, Invitrogen, CA), day 5 (close to Grade 1 cartilage damage), and day 9 (close to Grade 2 cartilage damage) post-monoiodoacetate intraarticular injections (Figure 1A, B). On day 21, all rats were euthanized two hours after the last exercise and their knees harvested. The cartilage damage in rats subjected to GTW was compared to cartilage damage in non-exercised rats on day 21 post-MIA inception. Rats were randomly assigned to 5 groups (n=15 rats/group): Cont, saline injected non-exercised sham controls; MIA21, MIA induced on day 0 and sacrificed on day 21, not exercised; MIA+GTW1-21, MIA induced on day 0, and subjected to GTW daily from days 1 to 21; MIA+GTW5-21, MIA induced on day 0, and subjected to GTW from day 5 to 21; MIA+GTW9-21, MIA induced on day 0, and subjected to GTW from day 9 to 21 (Figure 1A). In each group, femurs from 5 rats were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for molecular analysis, and femurs from 10 rats were fixed in 10% buffered formalin for macroscopic, microscopic or μCT imaging analyses. The cartilage damage was graded as described by Pritzker et al (28).

Figure 1.

Effects of GTW on the progression of MIA. (A) Experimental scheme. (B) Cartilage section showing dead (red) and live (green) cells on day 1 post-MIA inception. (C) Macroscopic, microscopic and bone imaging by μCT of: healthy sham control femur showing smooth surface, normal histology and no bone lesions on the femoral condyles and patellar grove (see Supplemental Data for 360° μCT projections) (a – d); MIA+GTW1-21 cartilage showing no surface abrasions on the condyles, some cartilage lesions on the patellar groove and ridges, near normal histology, and no bone involvement by μCT images (e – h); MIA+GTW5-21 cartilage showing some abrasions on condyles, cartilage damage on patellar groove and ridges, H&E section showing focal matrix condensation, cell clustering and disorganization, fibrocartilage formation, and some bone lesions by μCT images (i – l); MIA+GTW9-21 cartilage demonstrating extensive cartilage lesions on condyles and patellar groove, severe cartilage loss, denuded bone, and excessive bone lesions on femoral condyles and patellar grove in μCT images (m – p); MIA21 cartilage exhibiting cartilage matrix loss, delamination of superior surface, excavation and matrix loss in superficial and mid zone (q – t). Each femur is representative of each group showing similar characteristics (n=10).

RNA Extraction and Microarray Analysis

The cartilages from the distal end of individual femurs were examined under a stereomicroscope (Zeiss, Germany). Using a scalpel blade, cartilage from the distal end of femurs was carefully sliced off into small chips while maintained in a frozen state, avoiding the areas immediately around lesions to exclude tissue ingrowth in the lesions. The cartilage chips (approximately10 mg/femur) from individual femur were separately collected, and pulverized in a Mikrodismembrator-S (Sartorious, France) at 2500 rpm for 30 seconds. RNA was extracted with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, CA) (29), and analyzed in a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, CA) to ensure integrity.

RNA (300 ng) from three independent samples/group was used for cDNA synthesis and labeling using GeneChip Whole Transcript (WT) cDNA Synthesis and Amplification Kit, and GeneChip WT Terminal Labeling Kit, respectively (Affymetrix, CA). The labeled cDNA samples were hybridized on Affymetrix GeneChips Rat Gene 1.0 ST Array and scanned at the Microarray Shared Resource Facility at the OSU.

The intensity scans from three independent GeneChips per treatment group were subjected to gene expression analysis using Partek Genomic Suite version 6.4 (Partek Inc., MO). The significance of differences among the groups was calculated by the analysis of variance (ANOVA) and only significantly differentially regulated transcripts (p < 0.05) were considered for further analyses. Variations among the samples in each group were examined by Principal Components Analysis (PCA), and subjected to hierarchical and partition clustering by Partek Genomic Suite.

Functional Gene Network Analysis

The gene expression data derived from microarray analysis was subjected to Ingenuity Pathways Analysis (IPA, Ingenuity Systems, CA) to generate functional molecular networks. A fold-change cutoff of 2.0 was set to identify and assign the molecules to the Ingenuity’s Knowledge Base. The gene expression changes were considered in the context of physical, transcriptional or enzymatic interactions of the gene/gene products, and then grouped according to interacting gene networks. A detailed methodology to generate functional molecular relationships involving differentially regulated anabolic and catabolic networks is described in the Results section.

Validation of salient genes differentially expressed in the cluster analysis

Expression of selected genes from cluster analysis was confirmed by real-time (rt)-PCR (13). Briefly, first strand cDNA was synthesized from RNA using the Superscript III Reverse Transcriptase Kit (Invitrogen, CA). Gene expression was assessed by amplifying the cDNA with custom-designed primers using the iCycler iQ Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad, CA). The primers used were: Rps18-sense 5′-GCGGCGGAAAATAGCCTTCG-3′; Rps18-anti-sense 5′-GGCCAGTGGTCTTGGTGTGCTG-3′; Fcgr1a-sense 5′-AGCGGCATCTATCACTGCTCA-3′; Fcgr1a-anti-sense 5′-TCAGCACTGGTGTGGCAAATA-3′; Aspn-sense 5′-CAAAGAGCCAGTGAACCCCTT-3′; Aspn-anti-sense 5′-TCAGAACAGTGGACGACTCGA-3′; Mmp12-sense 5′-CCAGGAAATGCAGCAGTTCTTT-3′; Mmp12-anti-sense 5′-GCTGTACATCAGGCACTCCACAT-3′; Alox5-sense 5′-TTCTCCGCACACATCTGGTGT-3′; Alox5-anti-sense 5′-GGCAATGGTGAACCTCACATG-3′; Vcam1-sense 5′-GCCGGTCATGGTCAAGTGTTT-3′; Vcam1-anti-sense 5′-CATGAGACGGTCACCCTTGAA-3′; Cilp-sense 5′-TGTGAAGTCCAAGGTCACCCA-3′; Cilp-anti-sense 5′-GTAGAAGGAGTTGGTGGCATTCTG-3′; Sox9-sense 5′-ATCTGAAGAAGGAGAGCGAG-3′; Sox9-anti-sense 5′-CAAGCTCTGGAGACTGCTGA-3′; Col9a1-sense 5′-TGATGGCTTTGCTGTGCTG-3′; Col9a1-anti-sense 5′-TGACTGGCAGTTCATGGCA-3′; Frzb- sense 5′-TGCCCTCCCCTCAGTGTTAAT-3′; Frzb-anti-sense 5′-CAAGCCGATCCTTCCACTTCT-3′; Col2a1-sense 5′-ATGAGGGCCGAGGGCAACAG-3′; Col2a1-anti-sense 5′-GATGTCCATGGGTGCAATGTCAA-3′.

Statistical Analysis

The significance among the conditions in the microarray data was tested by Partek Genomic suite by ANOVA among the experimental groups (n=3). ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test by SPSS v17 was used to determine the significance levels of rt-PCR data that include two additional independent samples per group to microarray-examined specimens (n = 5). p < 0.05 was regarded as significant.

RESULTS

GTW prevents progression of cartilage destruction when implemented at the early stages of MIA

Comparing the anatomy/morphology of MIA+GTW1-21 to non-exercised MIA21 femoral cartilage revealed that exercise significantly prevented progression of MIA. This was evident from smooth surface, minimal aberrations or lesions on the cartilage surface of MIA+GTW1-21. The histological examination of MIA+GTW1-21 cartilage revealed slight thinning of cartilage in small areas, whereas cartilage and subchondral bone was preserved with no signs of bony changes (Figure 1Ce–h). The μCT images confirmed that early intervention by exercise prevented bone erosion as compared to non-exercised cartilage of MIA21 (Figure 1Ct).

We next determined whether exercise could prevent or delay progression of MIA in rats with close to Grade 1 cartilage damage. Analysis of MIA+GTW5-21 femurs revealed that GTW appeared to delay the progression of MIA, as evident by the relatively smooth condylar surface and absence of abrasions (Figure 1Ci–l). Histological analysis showed close to Grade 1.5–2 damage, as compared to non-exercised MIA21 cartilage showing Grade 3–3.5 damage. In parallel, μCT images showed reduced severity of bone erosion in MIA+GTW5-21 femurs (Figure 1Cl). Contrarily, initiation of GTW 9 days following inception of MIA (MIA+GTW9-21), resulted in close to Grade 4 or greater damage, showing denuded cartilage and sclerotic subchondral bone that covered the femoral condyles, patellar groove and ridges. Imaging by μCT also confirmed greater bone loss on both the femoral condyles and patellar groves (Figure 1Cp), when compared to bone damage in MIA21 (Figure 1Ct).

Extent of cartilage damage at the inception of GTW critically influences the expression of catabolic and anabolic genes

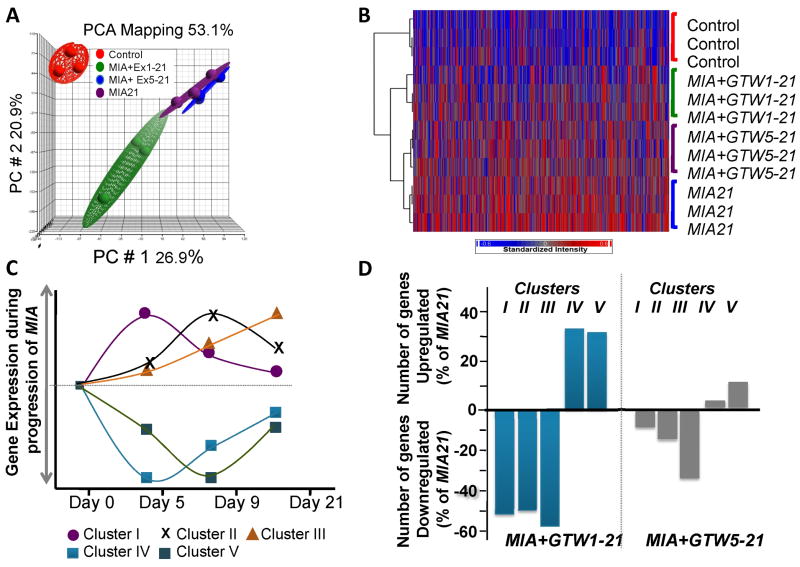

The RNA from the femoral cartilage of rats in MIA21, MIA+GTW1-21 and MIA+GTW5-21 were subjected to microarray analysis and their gene expression compared. Due to limited cartilage remaining on the condyles, MIA+GTW9-21 samples were excluded from this analysis. PCA revealed significantly distinct distribution of gene expression among samples in each group (n=3) (Figure 2A), as evident by the average F ratio (signal to noise ratio) of 15.5 in a total of 27,342 transcripts on the Affymetrix GeneChips array. The hierarchical clustering of the differentially regulated genes (2 fold change, p<0.05) showed that: (i) Cont cartilage showed minimal active genes (red) and maximal number of quiescent genes (blue); (ii) MIA21 regulated maximal number (1179, 4.29%) of transcripts; (iii) MIA+GTW1-21 regulated 847 (3.09%) transcripts, with gene expression pattern closer to that of Cont; (iv) MIA+GTW5-21 regulated 1103 (4.03%) transcripts, with gene expression pattern closer to MIA21 (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Transcriptome-wide microarray analysis of femoral cartilage from Cont healthy joints or from MIA+GTW1-21, MIA+GTW5-21 or MIA21 joints. (A) PCA analysis showing reproducible gene expression in the articular cartilage from the right knee joint of 3 separate rats from Cont, MIA+Ex1-21, MIA+GTW5-21 or MIA21. (B) Overall gene expression profiles of the articular cartilage of 3 separate rats from Cont, MIA+GTW1-21, MIA+GTW5-21 or MIA21 groups. Intensity plot with dendrogram represents the transcripts that were significantly (p < 0.05) and differentially upregulated (red) or downregulated (blue) by more than two-fold. The analysis shows the most differential changes in gene expression in MIA+GTW1-21, followed by MIA+GTW5-21 as compared to gene expression in MIA21 cartilage. (C) Temporal regulation of MIA associated Gene Clusters associated with: acute and innate immune responses (Cluster I); chronic inflammatory responses and genetic disorders (Cluster II); musculoskeletal disorders and inflammatory diseases (Cluster III); and genetic disorders and skeletal and muscular disorders (Cluster IV and V). (D) The percentage of genes that were significantly (p<0.05) up or downregulated by exercise (MIA+GTW1-21 and MIA+GTW5-21) in gene Clusters I, II, III, IV and V in comparison to genes regulated in MIA21.

MIA afflicted knees showed a temporal gene regulation pattern during the progression of cartilage damage (Figure 2C). The differentially expressed genes identified here could be categorized into 5 clusters: Cluster I, immune responses and innate immunity showing peak-upregulation in cartilage with Grade 1 damage (day 5 after MIA inception); Cluster II, chronic immune responses and immune trafficking showing peak-upregulation in cartilage with close to Grade 2 damage (day 9); Cluster III, chronic inflammatory diseases and immune suppression/adaptation exhibiting gradual increase in gene expression until cartilage showed close to Grade 3 to 3.5 damage (day 21); Cluster IV, musculoskeletal development and function associated genes showing peak downregulation in cartilage with Grade 1 damage (day 5); and Cluster V, genetic disorders and skeletal and musculoskeletal diseases associated genes showing peak downregulation in cartilage with Grade 2 damage (day 9). We next examined the effects of GTW as a mode of exercise on genes in each Cluster with respect to those in MIA21 (Figure 2D). Intervention by GTW in MIA+GTW1-21 suppressed approximately 52%, 50% and 59% of the genes upregulated in MIA21 in the inflammatory Clusters I, II and III, respectively. In parallel, GTW upregulated approximately 33% and 31% of the genes that were suppressed in MIA21, in Clusters IV and V, respectively. However, when exercise was initiated after Grade 1 cartilage damage (MIA+GTW5-21), the suppression of genes in Clusters I, II, and III was only 6%, 14% and 32%, respectively. Similarly, less than 3% genes in Cluster IV and 11% genes in Cluster V were upregulated in MIA+GTW5-21 (Figure 2D).

Table 1 shows salient differentially regulated genes by various exercise regimens (MIA+GTW1-21 and MIA+GTW5-21) as compared to MIA21. The major genes suppressed by GTW in MIA+GTW1-21 in Cluster I were Alox5ap (arachidonate 5-lipooxygenase activating protein required for Alox activation), Fcgr1a (Cd64, high affinity immunoglobulin gamma Fc receptor I, regulates innate/specific immune responses), Hla-dmb (HLA class II antigen beta-chain), Cd53 (surface molecule regulates innate levels of TNF-α), Aspn (asporin, negatively regulates TGF-β), Calcr (calcitonin receptor, involved in bone formation), Ctsg (cathepsin G, a peptidase), and Il1rl1 (IL-1 receptor like-1). The Cluster II genes downregulated by GTW were Cd84 (adherence associated molecule), Il-18 (Interleukin-18), Mmp-12 (elastase), Mmp-19 (involved in tissue remodeling), Adamts4 (aggrecanase), Adamts7 (degrades cartilage oligomeric protein), Ccr1 (chemokine receptor 1, chemoattracts cells), and Ccl9 (osteoclast activation through Ccr1). The genes suppressed in Cluster III included Alox5, Clec4d (C-type lectin domain family 4 involved in antigen uptake), Vcam1 (vascular cell adhesion molecule-1), Adam23 (disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain-containing protein 23 involved in cell adhesion), Postn (periostin, involved in bone formation), and Crlf1 (cytokine receptor-like factor 1), all of which are involved in chronic inflammation. More importantly, in Clusters IV and V, GTW upregulated expression of extracellular matrix associated genes that were suppressed in MIA21. Cluster IV included Cilp (cartilage intermediate layer protein), Cilp2, Acan (aggrecan), Sox9 (transcription factor required for chondrocyte matrix proteins), Cytl1 (cytokine like-1, promotes proteoglycan synthesis), Crlf1 (cytokine receptor-like factor 1), Igf2 (insulin like growth factor II, chondrocyte growth and differentiation). Similarly, genes upregulated by GTW in Cluster V were Collagens (Col2a1, Col9a1, Col9a2, Col9a3, Col11a2), Matn3 (matrilin 3), Frzb (Wnt signaling inhibitor), Mia (melanoma-derived growth regulatory protein), Chad (chondroadherin, mediates chondrocyte adhesion), Hapln1 (hyaluronan and proteoglycan link protein 1), Vit (vitrin, promotes matrix assembly) and Prg4 (Lubricin). On the other hand, cartilage from MIA+GTW5-21 exhibited that GTW only partially upregulated genes suppressed in MIA21.

Table 1.

GTW-induced differential expression of salient genes in MIA afflicted cartilage.

|

Cluster I | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gene | MIA+GTW 1-21 (%MIA21) | MIA+GTW 5-21 (%MIA21) |

| Alox5ap | −206 | −119 |

| Calcr | −183 | −136 |

| Fcgr1a | −182 | −101 |

| Tlr7 | −179 | +115 |

| C3 | −178 | −104 |

| Hla-dmb | −176 | +130 |

| Cd53 | −169 | −122 |

| Aspn | −166 | +148 |

| Ctsg | −126 | +106 |

| Il1rl1 | −124 | +156 |

|

Cluster II | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gene | MIA+GTW1-21 (%MIA21) | MIA+GTW 5-21 (%MIA21) |

| Cd84 | −161 | −133 |

| Il18 | −149 | −102 |

| Mmp12 | −144 | +130 |

| Cd44 | −140 | −104 |

| Tnfsf13 | −140 | −103 |

| Adamts7 | −136 | −112 |

| Adamts4 | −118 | −185 |

| Ccl9 | −117 | +125 |

| Ccr1 | −112 | −117 |

| Mmp19 | −110 | −121 |

|

Cluster III | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gene | MIA+ GTW1-21 (%MIA21) | MIA+GTW5-21 (%MIA21) |

| Clec4d | −209 | +103 |

| Alox5 | −193 | −126 |

| Vcam1 | −171 | −102 |

| Adam23 | −138 | +103 |

| Crlf1 | −131 | −126 |

| Cdh13 | −125 | −139 |

| Postn | −122 | +123 |

| C1s | −120 | −142 |

| Serpine1 | −119 | +101 |

| Cd14 | −115 | −152 |

|

Cluster IV | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gene | MIA+ GTW1-21 (%MIA21) | MIA+GTW5-21 (%MIA21) |

| Cilp | +445 | −104 |

| Cytl1 | +226 | −107 |

| Cilp2 | +210 | −156 |

| Hapln3 | +158 | +103 |

| Acan | +152 | −110 |

| Sox9 | +150 | −123 |

| Gdf10 | +140 | −176 |

| Igf2 | +139 | +136 |

| Casr | +139 | −219 |

| Chst3 | +114 | −128 |

|

Cluster V | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gene | MIA+GTW1-21 (%MIA21) | MIA+GTW5-21 (%MIA21) |

| Col9a1 | +1102 | +341 |

| Matn3 | +979 | +322 |

| Frzb | +761 | +129 |

| Mia | +381 | +229 |

| Col2a1 | +324 | +109 |

| Chad | +287 | −101 |

| Hapln1 | +277 | +108 |

| Col11a2 | +264 | +126 |

| Vit | +251 | −101 |

| Prg4 | +165 | −140 |

The extent of cartilage damage at the initiation of GTW determines its effectiveness through the differential regulation of major intracellular pathways

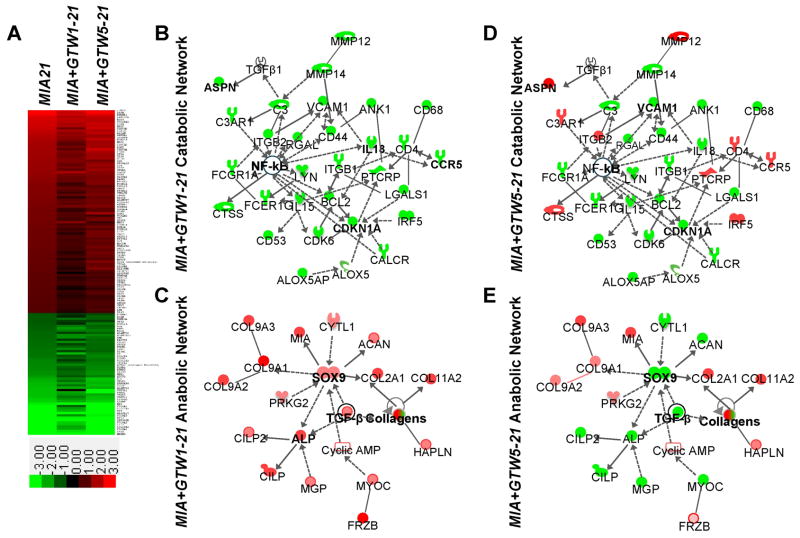

Among 1179 genes regulated more than 2-fold (p<0.05) in MIA21, 142 genes were included in human and experimental ‘arthritis’ disease category in the Ingenuity’s Knowledge Database. These 142 genes clustered to show the general trends regulated by exercise. This analysis showed that intervention by GTW in MIA+GTW1-21 suppressed 96% genes that are upregulated in MIA21 (red in the intensity plot), and upregulated 81% genes that are downregulated in MIA21 (green in the intensity plot), as evident by color shifting toward darker shades, i.e., closer to control levels. Contrarily, GTW when initiated after 5 days of the onset of MIA (MIA+GTW5-21), suppressed 80% genes upregulated in MIA21, and upregulated only 58% genes that are downregulated in MIA21 (Figure 3A).

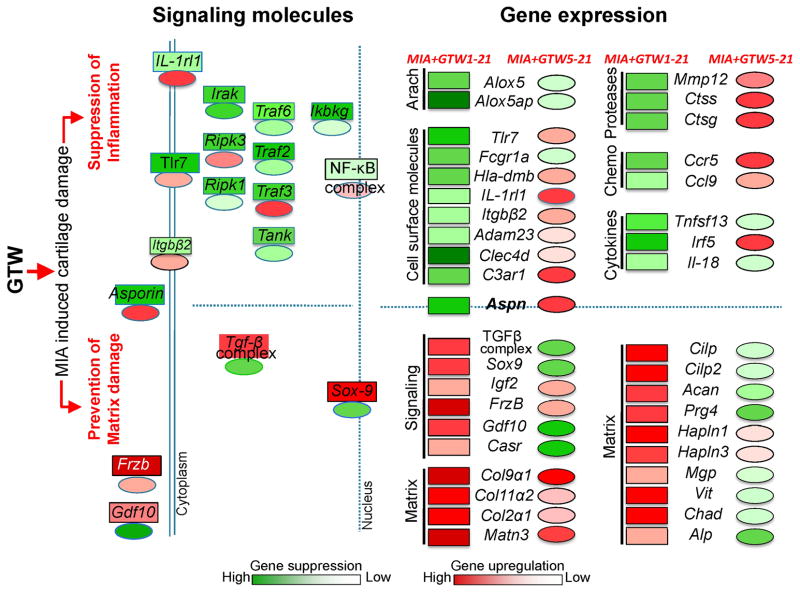

Figure 3.

Catabolic and anabolic networks regulated by GTW in MIA. (A) Intensity plot of 142 genes that are a known set of arthritis-associated genes in Ingenuity Knowledge Database, and more than 2-fold up (red) or down (green) regulated in MIA21 (see Supplemental Data for details). (B–E) IPA generated networks of: (B) catabolic genes that are downregulated by GTW in MIA+GTW1-21 showing suppression of genes involved in acute and chronic inflammatory/immune responses via the suppression of NF-κB activity; (C) anabolic genes that are upregulated by exercise in MIA+GTW1-21 showing induction of Sox9 and TGF-β that in turn may upregulate the expression of matrix associated genes; (D) catabolic gene regulation by GTW in MIA+GTW5-21 showing partial suppression of genes involved in acute and chronic immune responses; (E) anabolic gene regulation by GTW in MIA+GTW5-21 showing suppression of Sox9 and TGF-β and number of matrix proteins that may limit its ability to repair cartilage. Red, green, and white colors represent upregulation, downregulation and no regulation, respectively. The shading of colors represents dark, greater changes to light lesser changes. Symbols are:  cytokine/growth factor,

cytokine/growth factor,  phosphatase,

phosphatase,  Transcription regulator,

Transcription regulator,  translation regulator,

translation regulator,  transmembrane receptor,

transmembrane receptor,  complex group,

complex group,  enzyme,

enzyme,  G protein coupled receptor,

G protein coupled receptor,  kinase,

kinase,  peptidase, and

peptidase, and  other.

other.

During the progression of MIA, NF-κB and TGF-β play a focal role in regulating gene expression in the inflammatory Clusters I, II and III and the anabolic Clusters IV and V. Consequently, the functional relationships among NF-κB, TGF-β and 142 arthritis-related genes were analyzed using an IPA custom molecular network generation tool (Network Explorer) (Figure 3B–E). This analysis revealed that the catabolic gene networks induced during the progression of MIA, were downregulated (green symbols) by GTW in MIA+GTW1-21 likely via suppression of NF-κB activity, a major node in this network (Figure 3B). The NF-κB in turn may regulate arachidonate-lipoxygenase pathway (Alox5, Alox5ap), adherence molecules (Itgb1, Itgal, Vcam1, Cd44), cell cycle associated genes (Ck6, Cdkn1a, Bcl2, Ank1), cytokines (Il-18, Il-15), and MMPs (Mmp12, Mmp14). Similarly GTW in MIA+GTW1-21 upregulated anabolic gene networks via Tgf-β and Sox9. These growth factors and transcription factors have been shown to regulate the expression of Collagens (Col type IIα1, Col type IXα1, Col type IX α2, Col type IX α3, Col type XI α2), Cilp (cartilage intermediate layer protein), Cilp2, Mgp (matrix gla protein), Acan (Aggrecan), and other matrix proteins (Figure 3C red symbols; Table 1). The same arthritis-associated networks in MIA+GTW5-21 demonstrated that intervention by GTW even after Grade 1 cartilage damage, suppressed several genes associated with NF-κB activity (Figure 3D). Contrarily, several proinflammatory genes such as Aspn, Mmp-12, Ccl9, interferon regulatory factor 5 (Irf5), integrin beta 2 (Itgb2), and cathepsin G (Ctsg), periostin (Postn) were not suppressed or upregulated by GTW when implemented following Grade 1 cartilage damage (Figure 3E). Additionally, in MIA+GTW5-21, Sox9 was further suppressed and together with Tgf-β likely led to the downregulation of Acan, Alp, Cilp, Cilp2, and Mgp required for matrix assembly. Nevertheless, the expression of Collagens (ColIXa1, ColIXa2, ColIXa3, ColIIa1, ColXIa2) was upregulated in MIA+GTW5-21 as compared to MIA21 (Figure 3E).

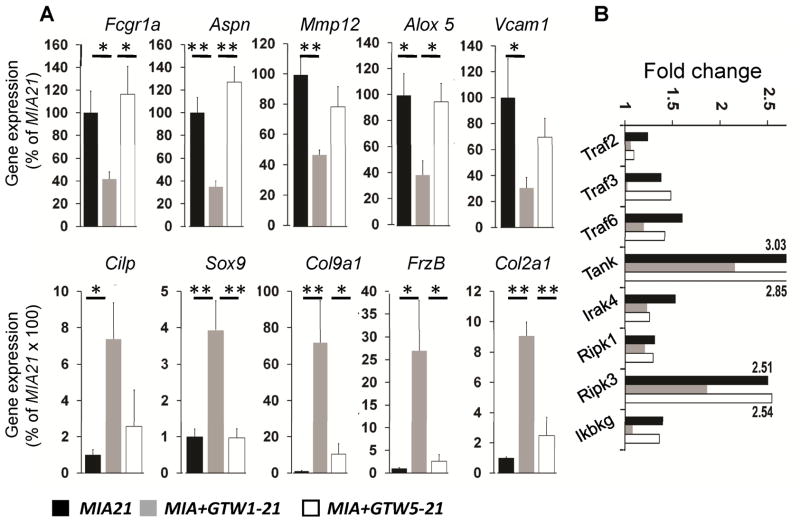

Real-time-PCR validated the microarray findings showing differential downregulation of the salient genes in Clusters I, II and III (Fcgr1a, Aspn, Mmp12, Alox5, Vcam1), and upregulation of the genes in Clusters IV and V (Cilp, Sox9, Col9a1, Frzb, Col2a1) by GTW in MIA+GTW1-21 and MIA+GTW5-21 (Figure 4A). The IPA showed that the regulation of NF-κB may play a focal role in the antiinflammatory effects of GTW. Since NF-κB activity in the cells is shown to be oscillatory (30, 31) and thus may not provide the true activation state in the inflamed knees, we examined the expression of several signaling molecules in the NF-κB pathway. As shown in Figure 4B, GTW in MIA+GTW1-21 suppressed Traf2 (TNF receptor associated factor 2), Traf3, Traf6, Tank (TRAF family member-associated NF-kappa-B activator), Ripk1 (Receptor (TNFRSF) interacting Ser-Thr kinase), Ripk3, and Ikbkg (I-κb kinase γ/IKKγ) expression, that were upregulated in MIA afflicted knees. However, GTW prevented expression of fewer MIA-induced genes, e.g., Traf3, Tank, Ripk3, and Ikbkg when it was initiated in rats with Grade 1 cartilage damage (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

(A) Genes selected from each Cluster to demonstrate their up- or downregulation by quantitative rt-PCR analysis in MIA+GTW1-21 or MIA+GTW5-21 cartilage, as compared to MIA21 cartilage. Fcgr1a (IgG Fc receptor gamma 1a), Aspn (Asporin), Mmp12 (Matrix metalloproteinase 12), Alox5 (Arachidonate-5-lipoxygenase), Vcam1 (vascular endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1), Cilp (cartilage intermediate layer protein), Sox9 (Sry-related HMG box -9), Col9α1 (Collagen type 9α1), Frzb (Frizzled B), Col2α1 (Collagen type 2α1). Data represents rt-PCR analysis performed on RNA from five separate rats in each group. The * and ** indicate significance values of p > 0.05 and p > 0.01, respectively. (B) Regulation of the genes required for the activation of NF-κB by GTW. Suppression of Traf2 (TNF receptor associated factor), Traf3, Traf6, Tank (TRAF family member-associated NF-kappa-B activator), Ripk1 (Receptor (TNFRSF) interacting Ser-Thr kinase), Ripk3, Ikbkg (I-κb kinase γ/IKK γ) expression in MIA+GTW1-21and MIA+GTW5-21, as compared to MIA21 in the microarray data. Upregulation of the gene expression in MIA21 was compared to Cont. Each point represents mean of microarray data derived from 3 independent cartilage specimens (p<0.05).

DISCUSSION

The present study documents the effects of GTW as a form of exercise on the global gene regulation in the articular cartilage of the knee afflicted with various stages of MIA. In MIA, acute and chronic inflammations drive the destruction of the knee, whereas inhibition of matrix synthesis and its breakdown prevent the repair that worsens the joint damage (32–35). We showed that GTW suppresses inflammation and upregulates repair to prevent active progression of cartilage damage. Nevertheless, the maximal effects were observed when GTW was implemented on the knees with Grade 1 or lesser cartilage damage. Contrarily, when the knees with Grade 2 damage were subjected to GTW, its effectiveness was compromised, and the cartilage damage was further intensified as compared to MIA21. Benefits of exercise in the form of GTW are likely contingent upon many factors including adherence to exercise regimens, frequency of exercise, speed of walking, range of motion, and actual loading of the symptomatic compartment. Furthermore, efficacy of exercise on various stages of arthritic lesions is less predictable, mainly due to the limitations in detecting the extent of cartilage damage in humans (36–38). In the present model of MIA, our observations indicate that the extent of cartilage damage may also play an important role in achieving the optimal effects of gentle exercise.

The major limitation of the MIA model used in the present study is that monoiodoacetate induces aggressive cartilage destruction, which progresses to Grade 3 to 3.5 damage within 21 days. Thus, these lesions may not depict cartilage damage caused by trauma/insult that takes extended periods of time in human OA (23). This is an important limitation that must be considered when trying to extend/translate these findings to humans with arthritis. Nevertheless, it is important to note that even during this aggressive progression of cartilage destruction, GTW could suppress progression of inflammation and cartilage loss, as evident from macroscopic, microscopic and μCT imaging. In support of exercise-mediated joint function, it is recently reported in a cohort of 2589 OA patients that the extent of physical activity and better joint performance are proportionally related (39).

Presently, both resistance and gentle exercises are prescribed for rehabilitation of injured or arthritic knees. However, the optimal duration and physical loading necessary for achieving the beneficial effects of exercise are unclear. In the present study, we subjected knees to 45 minutes of GTW, at a rate of 12 meters/minute. Considering the aggressive nature of the MIA model used, the selected speed and duration of GTW were gentler than those used in the earlier experimental models, e.g., 16 meters/min for 1h (27). The effects of longer or shorter duration or different speeds of GTW are yet to be determined. For example, a different exercise regimen on MIA+GTW5-21 may have potentially prevented cartilage damage more effectively. Interestingly, even a single bout of exercise (90° knee bending for 250 times) is shown to increase IL-10 and suppress release of cartilage oligomeric protein and aggrecan levels in intra-articular and peri-synovial fluids from osteoarthritic knees (20). These findings further support that exercise may act as an antiinflammatory and reparative signal on inflamed knees.

The information gained from the transcriptome-wide gene expression analysis demonstrated that counteracting the MIA induced gene induction or suppression appears to be a primary mechanism underlying the GTW-mediated inhibition of cartilage damage. GTW suppresses expression of significant number of innate and chronic immunity related genes (Clusters I, II and III) demonstrating the potential of such exercises in suppressing inflammation. Additionally, GTW promotes repair by inducing the expression of genes related to musculoskeletal development and functions (Clusters IV and V) in MIA+GTW1-21. It is likely that, the partial success of GTW in limiting the existing cartilage damage in MIA+GTW5-21 may be related to its inability to inhibit/induce expression of some of these genes in catabolic and anabolic clusters. Specifically, NF- κB controls proinflammatory gene induction and plays a critical role during cartilage inflammation (24, 40–42). According to IPA network explorer, intervention by exercise in MIA+GTW1-21 may suppress NF-κB activity and thus genes associated with the NF-κB networks, such as those involved in apoptosis and cell cycle (Cdkn1a and Bcl2), cell adhesion (Itgb and Vcam), complement C3, matrix breakdown (Mmp-12 and Mmp-14), and proinflammatory responses (Il-15 and Il-18) (43–45). Interestingly, GTW suppressed fewer genes in the NF-kB signaling cascade that was also reflected in the lesser extent and number of proinflammatory genes suppressed in MIA+GTW5-21.

During inflammation, activation of proinflammatory cytokine receptors leads to sequential activation of receptor associated kinases, adaptor proteins, TRAFs, and IKK complex (IKKα and IKKβ kinases and IKKγ) which ultimately determines NF-κB activity (13). Figure 5 shows differential regulation of signaling molecules and gene expression when GTW was implemented 1 day or 5 days after the onset of MIA. For example, Ikbkg (IKKγ), Traf2, Traf3, Traf6, Tank and Ripk essential to activate IKK complex were significantly suppressed by GTW initiated on day 1 post-MIA induction. Expression of Irak4, which is required to recruit TRAF6 into the signaling complex, was also suppressed by exercise in MIA+GTW1-21. Additionally, RIP kinases that activate RIP to bind IKKγ and recruit it to the TNFR1 signaling complex independent of TRAF, are also suppressed in MIA+GTW1-21 (30). These findings further suggest that exercise may collectively suppress gene expression required for NF-κB activity and thus inflammation. In this context, the inability of GTW in MIA+GTW5-21 to suppress Traf3, Tank, Ripk1, Ripk3, and Ikbkg may be responsible for only partial prevention of the progression of MIA (Figure 5). Previous in-vitro studies showing that antiinflammatory actions of mechanical signals are mediated by suppression of NF-κB activation via TAK1, IKK, and I-κB also support the present findings (13, 24, 40, 42). Additionally, the antiinflammatory effects of exercise have been shown in arthritis and other conditions. For example, exercise is shown to increase levels of antiinflammatory cytokine IL-10 in the intra-articular and peri-synovial fluids of patients with osteoarthritis (19), suppress low-grade systemic inflammation (20), decrease inflammation in diabetes (46), and suppress IL-8, C reactive protein and interferon-γ in fibromyalgia patients (47). These findings demonstrate that in addition to local effects, exercise exerts systemic effects. Whether exercise also suppresses systemic markers associated with cartilage damage in MIA is yet to be determined.

Figure 5.

Schematic showing the molecular basis of the protective effects of GTW on MIA-induced cartilage damage. GTW preserves cartilage integrity by preventing MIA-induced inflammation and matrix loss in MIA+GTW1-21 (rectangles) to a greater extent than in MIA+GTW5-21 (ovals), where GTW was applied following Grade 1 cartilage damage. These differential effects stem from the ability of GTW to suppress (green) MIA-induced NF-κB signaling molecules in MIA+GTW1-21, as compared to minimal suppression or upregulation (red) of these molecules in MIA+GTW5-21. This in turn may suppress several proinflammatory genes [arachidonate metabolites (Arach), receptors, proteases, chemokines (Chemo) and cytokines] in MIA+GTW1-21, but to a lesser degree in MIA+GTW5-21. Importantly, Aspn, an inhibitor of TGF-β that is upregulated in MIA21, is significantly suppressed by GTW in MIA+GTW1-21. By suppressing Asporin expression, GTW may upregulate TGF-β complex and SOX-9 in MIA+GTW1-21, required for synthesis of matrix proteins. Simultaneous upregulation of Frizzled-related protein (Frzb) likely inhibit chondrocyte hypertrophy and mineralization (50). Contrarily, the lack of Asporin suppression and thus failure of the expression of the molecules in TGF-β complex and Sox-9 in MIA+GTW5-21 may prevent MIA-induced matrix loss to a lesser extent, as evidenced by the suppression of several molecules required for matrix assembly.

In the context of GTW preventing matrix loss, the schematic in Figure 5 shows the regulation of signaling molecules and matrix proteins by GTW in MIA afflicted cartilage. MIA significantly upregulates Aspn, a known inhibitor of TGF-β (48). Strikingly, GTW significantly suppresses Aspn expression with parallel upregulation of molecules in TGF-β complex in MIA+GTW1-21 cartilage. The anabolic networks of TGF-β may upregulate Sox9 and together may serve as focal points for the significant upregulation of many chondrocytic matrix associated genes such as aggrecan, collagens, Cilp, Cilp2, Matn3 and Vit by exercise in MIA+GTW1-21. Contrarily, failure of asporin suppression in MIA+GTW5-21 may be responsible for the partial repair of MIA-afflicted cartilage. This dynamic downregulation of TGF-β via Aspn induction in MIA21 and counter regulation by GTW suggests an important role of Aspn in exercise-mediated anabolic responses in cartilage (48, 49). Interestingly, cartilage is believed to have very limited capacity to regenerate/repair. The present findings are novel in showing that exercise such as GTW can augment anabolic gene expression to prevent cartilage loss and matrix restructuring in inflamed cartilage.

Overall, the present study is the first to delineate the molecular basis for the efficacy of GTW in suppressing progression of cartilage destruction. We show that GTW is a robust regulator of anti-catabolic and anabolic networks that suppress inflammation and upregulate matrix synthesis, even during actively progressing cartilage destruction. Importantly, the effects of exercise appear to be inversely related to the extent of cartilage damage, i.e., its implementation at the earlier stages of cartilage damage may provide the greater benefits. Further studies are required to understand how these robust therapeutic effects of exercise can be optimized to prevent cartilage destruction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant number AR048781 from the National Institute of Arthritis, Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, DE015399 and DE014320 from the National Institute of Craniofacial and Dental Research at the National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD.

Financial Support information. Authors acknowledge that no financial support or other benefits from commercial sources was received for the work reported in the manuscript.

Footnotes

All authors did not have any other financial interests that may create a potential conflict of interest or the appearance of a conflict of interest with regard to the present work.

References

- 1.Hootman JM. Osteoarthritis in elderly persons: risks of exercise and exercise as therapy. Clin J Sport Med. 2010;20:223. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e3181dd984a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunter DJ, Lo GH. The management of osteoarthritis: an overview and call to appropriate conservative treatment. Med Clin North Am. 2009;93:127–43. xi. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang W, Nuki G, Moskowitz RW, Abramson S, Altman RD, Arden NK, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis: part III: Changes in evidence following systematic cumulative update of research published through January 2009. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18:476–99. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunlop DD, Semanik P, Song J, Sharma L, Nevitt M, Jackson R, et al. Moving to maintain function in knee osteoarthritis: evidence from the osteoarthritis initiative. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91:714–21. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Penninx BW, Messier SP, Rejeski WJ, Williamson JD, DiBari M, Cavazzini C, et al. Physical exercise and the prevention of disability in activities of daily living in older persons with osteoarthritis. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:2309–16. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.19.2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Felson DT. Risk factors for osteoarthritis: understanding joint vulnerability. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004:S16–21. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000144971.12731.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lohmander LS, Roos EM. Clinical update: treating osteoarthritis. Lancet. 2007;370:2082–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61879-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lund H. Invited commentary. Phys Ther. 2008;88:1121–2. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20080077.ic. author reply 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis: the semantics of differences and changes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18:473–5. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Darling EM, Athanasiou KA. Biomechanical strategies for articular cartilage regeneration. Ann Biomed Eng. 2003;31:1114–24. doi: 10.1114/1.1603752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith RL, Carter DR, Schurman DJ. Pressure and shear differentially alter human articular chondrocyte metabolism: a review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004:S89–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agarwal S, Deschner J, Long P, Verma A, Hofman C, Evans CH, et al. Role of NF-kappaB transcription factors in antiinflammatory and proinflammatory actions of mechanical signals. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:3541–8. doi: 10.1002/art.20601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nam J, Aguda BD, Rath B, Agarwal S. Biomechanical thresholds regulate inflammation through the NF-kappaB pathway: experiments and modeling. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5262. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Felson DT, Gross KD, Nevitt MC, Yang M, Lane NE, Torner JC, et al. The effects of impaired joint position sense on the development and progression of pain and structural damage in knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:1070–6. doi: 10.1002/art.24606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guilak F, Fermor B, Keefe FJ, Kraus VB, Olson SA, Pisetsky DS, et al. The role of biomechanics and inflammation in cartilage injury and repair. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004:17–26. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000131233.83640.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rolauffs B, Muehleman C, Li J, Kurz B, Kuettner KE, Frank E, et al. Vulnerability of the superficial zone of immature articular cartilage to compressive injury. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:3016–27. doi: 10.1002/art.27610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roos EM. Joint injury causes knee osteoarthritis in young adults. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2005;17:195–200. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000151406.64393.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferretti M, Gassner R, Wang Z, Perera P, Deschner J, Sowa G, et al. Biomechanical signals suppress proinflammatory responses in cartilage: early events in experimental antigen-induced arthritis. J Immunol. 2006;177:8757–66. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.12.8757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Helmark IC, Mikkelsen UR, Borglum J, Rothe A, Petersen MC, Andersen O, et al. Exercise increases interleukin-10 levels both intraarticularly and peri-synovially in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R126. doi: 10.1186/ar3064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mathur N, Pedersen BK. Exercise as a mean to control low-grade systemic inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. 2008;2008:109502. doi: 10.1155/2008/109502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pedersen BK. The anti-inflammatory effect of exercise: its role in diabetes and cardiovascular disease control. Essays Biochem. 2006;42:105–17. doi: 10.1042/bse0420105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vanwanseele B, Eckstein F, Knecht H, Spaepen A, Stussi E. Longitudinal analysis of cartilage atrophy in the knees of patients with spinal cord injury. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:3377–81. doi: 10.1002/art.11367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guzman RE, Evans MG, Bove S, Morenko B, Kilgore K. Mono-iodoacetate-induced histologic changes in subchondral bone and articular cartilage of rat femorotibial joints: An animal model of osteoarthritis. Toxicologic Pathology. 2003;31:619–24. doi: 10.1080/01926230390241800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akanji OO, Sakthithasan P, Salter DM, Chowdhury TT. Dynamic compression alters NFkappaB activation and IkappaB-alpha expression in IL-1beta-stimulated chondrocyte/agarose constructs. Inflamm Res. 2010;59:41–52. doi: 10.1007/s00011-009-0068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McNulty AL, Estes BT, Wilusz RE, Weinberg JB, Guilak F. Dynamic loading enhances integrative meniscal repair in the presence of interleukin-1. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18:830–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hunter DJ, Eckstein F. Exercise and osteoarthritis. J Anat. 2009;214:197–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2008.01013.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Butterfield TA, Leonard TR, Herzog W. Differential serial sarcomere number adaptations in knee extensor muscles of rats is contraction type dependent. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99:1352–8. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00481.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pritzker KP, Gay S, Jimenez SA, Ostergaard K, Pelletier JP, Revell PA, et al. Osteoarthritis cartilage histopathology: grading and staging. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14:13–29. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. The single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction: twenty-something years on. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:581–5. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Signaling to NF-kappaB. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2195–224. doi: 10.1101/gad.1228704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ihekwaba AE, Broomhead DS, Grimley RL, Benson N, Kell DB. Sensitivity analysis of parameters controlling oscillatory signalling in the NF-kappaB pathway: the roles of IKK and IkappaBalpha. Syst Biol (Stevenage) 2004;1:93–103. doi: 10.1049/sb:20045009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garvican ER, Vaughan-Thomas A, Innes JF, Clegg PD. Biomarkers of cartilage turnover. Part 1: Markers of collagen degradation and synthesis. Vet J. 2010;185:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kraus VB, Nevitt M, Sandell LJ. Summary of the OA biomarkers workshop 2009--biochemical biomarkers: biology, validation, and clinical studies. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18:742–5. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anghelina M, Sjostrom D, Perera P, Nam J, Knobloch T, Agarwal S. Regulation of biomechanical signals by NF-kappa B transcription factors in chondrocytes. 2008;2008:245–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Inoue H, Hiraoka K, Hoshino T, Okamoto M, Iwanaga T, Zenmyo M, et al. High levels of serum IL-18 promote cartilage loss through suppression of aggrecan synthesis. Bone. 2008;42:1102–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haaland DA, Sabljic TF, Baribeau DA, Mukovozov IM, Hart LE. Is regular exercise a friend or foe of the aging immune system? A systematic review. Clin J Sport Med. 2008;18:539–48. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e3181865eec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ornetti P, Brandt K, Hellio-Le Graverand MP, Hochberg M, Hunter DJ, Kloppenburg M, et al. OARSI-OMERACT definition of relevant radiological progression in hip/knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17:856–63. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roddy E, Zhang W, Doherty M, Arden NK, Barlow J, Birrell F, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for the role of exercise in the management of osteoarthritis of the hip or knee--the MOVE consensus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44:67–73. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dunlop DD, Song J, Semanik PA, Sharma L, Chang RW. Physical activity levels and functional performance in the osteoarthritis initiative: A graded relationship. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:127–36. doi: 10.1002/art.27760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dossumbekova A, Anghelina M, Madhavan S, He L, Quan N, Knobloch T, et al. Biomechanical signals inhibit IKK activity to attenuate NF-kappaB transcription activity in inflamed chondrocytes. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3284–96. doi: 10.1002/art.22933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Madhavan S, Anghelina M, Sjostrom D, Dossumbekova A, Guttridge DC, Agarwal S. Biomechanical signals suppress TAK1 activation to inhibit NF-kappaB transcriptional activation in fibrochondrocytes. J Immunol. 2007;179:6246–54. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.9.6246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marcu KB, Otero M, Olivotto E, Borzi RM, Goldring MB. NF-kappaB signaling: multiple angles to target OA. Curr Drug Targets. 2010;11:599–613. doi: 10.2174/138945010791011938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Geyer M, Grassel S, Straub RH, Schett G, Dinser R, Grifka J, et al. Differential transcriptome analysis of intraarticular lesional vs intact cartilage reveals new candidate genes in osteoarthritis pathophysiology. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17:328–35. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scanzello CR, Umoh E, Pessler F, Diaz-Torne C, Miles T, Dicarlo E, et al. Local cytokine profiles in knee osteoarthritis: elevated synovial fluid interleukin-15 differentiates early from end-stage disease. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17:1040–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schett G, Kiechl S, Bonora E, Zwerina J, Mayr A, Axmann R, et al. Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule 1 as a Predictor of Severe Osteoarthritis of the Hip and Knee Joints. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2009;60:2381–9. doi: 10.1002/art.24757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Belotto MF, Magdalon J, Rodrigues HG, Vinolo MA, Curi R, Pithon-Curi TC, et al. Moderate exercise improves leucocyte function and decreases inflammation in diabetes. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;162:237–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04240.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ortega E, Garcia JJ, Bote ME, Martin-Cordero L, Escalante Y, Saavedra JM, et al. Exercise in fibromyalgia and related inflammatory disorders: known effects and unknown chances. Exerc Immunol Rev. 2009;15:42–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nakajima M, Kizawa H, Saitoh M, Kou I, Miyazono K, Ikegawa S. Mechanisms for asporin function and regulation in articular cartilage. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282:32185–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700522200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ikenoue T, Trindade MC, Lee MS, Lin EY, Schurman DJ, Goodman SB, et al. Mechanoregulation of human articular chondrocyte aggrecan and type II collagen expression by intermittent hydrostatic pressure in vitro. J Orthop Res. 2003;21:110–6. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(02)00091-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lories RJ, Peeters J, Bakker A, Tylzanowski P, Derese I, Schrooten J, et al. Articular cartilage and biomechanical properties of the long bones in Frzb-knockout mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:4095–103. doi: 10.1002/art.23137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.