Abstract

Summary

Implementation of case findings according to guidelines for osteoporosis in fracture patients presenting at a Fracture Liaison Service (FLS) was evaluated. Despite one guideline, all FLSs differed in the performance of patient selection and prevalence of clinical risk factors (CRFs) indicating the need for more concrete and standardised guidelines.

Introduction

The aim of the study was to evaluate the implementation of case findings according to guidelines for osteoporosis in fracture patients presenting at FLSs in the Netherlands.

Methods

Five FLSs were contacted to participate in this prospective study. Patients older than 50 years with a recent clinical fracture who were able and were willing to participate in fracture risk evaluation were included. Performance was evaluated by criteria for patient recruitment, patient characteristics, nurse time, evaluated clinical risk factors (CRFs), bone mineral density (BMD) and laboratory testing and results of CRFs and BMD are presented. Differences between FLSs were analysed for performance (by chi-square and Student’s t test) and for prevalence of CRFs (by relative risks (RR)).

Results

All FLSs had a dedicated nurse spending 0.9 to 1.7 h per patient. During 39 to 58 months follow-up, 7,199 patients were evaluated (15 to 47 patients/centre/month; mean age, 67 years; 77% women). Major differences were found between FLSs in the performance of patient recruitment, evaluation of CRFs, BMD and laboratory testing, varying between 0% and 100%. The prevalence of CRFs and osteoporosis varied significantly between FLSs (RR between 1.7 and 37.0, depending on the risk factor).

Conclusion

All five participating FLSs with a dedicated fracture nurse differed in the performance of patient selection, CRFs and in the prevalence of CRFs, indicating the need for more concrete and standardised guidelines to organise evaluation of patients at the time of fracture in daily practice.

Keywords: Fracture liaison service, Fractures, Guideline implementation, Osteoporosis

Introduction

Osteoporotic fractures represent a major growing public health issue. The number of fractures in the elderly is expected to increase mainly due to the world’s ageing population [1]. Bone mineral density (BMD) measured by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan alone is not sufficient to provide an accurate prediction of fracture risk. Other clinical, non-BMD risk factors are known to be important for estimating an adequate probability of fracture [2, 3]. A previous fracture doubles the risk for future fractures and vertebral fractures quadruple this risk [4, 5] and even more so at short-term [6–10]. Recently, the World Health Organization developed a fracture risk assessment (FRAX) tool to evaluate the 10-year fracture risk of patients [11]. The FRAX tool integrated clinical risk factors (CRFs) and BMD to predict the 10-year risk of a major osteoporotic and hip fracture but does not include evaluation of fall risks.

Current guidelines on osteoporosis in the Netherlands (developed in 2002) recommend that all female patients over 50 years of age with a minimal trauma fracture should be investigated by DXA and treated, when having, for osteoporosis [12]. Moreover, women aged 60 years and over, with all three known risk factors for fractures: a family history of fractures, low body weight (<67 kg) or immobility, should be investigated by DXA scan for osteoporosis. Women over the age of 70 merely require two of these risk factors [12].

A fracture liaison service (FLS) is one of the initiatives in the field of post-fracture care to integrate osteoporosis assessment [13–16]. An evaluation of FLSs allowed to identify similarities and differences in the performance of evidence-based medicine and prevalence of CRFs and can be helpful to detect strengths and weaknesses of guideline advices and their implementation. The results of previous studies encouraged the start of several FLSs throughout the Netherlands [13–15, 17, 18].

The aim of the present study was to identify (1) similarities and differences in the performance and (2) the prevalence of CRFs in patients presented at FLSs in five large hospitals in the Netherlands.

Material and methods

Study design

This prospective, observational study was conducted in five FLSs of hospitals in the Netherlands, one university hospital and four general hospitals. These FLSs agreed to respond to an extensive questionnaire on organisational aspects, performance and results of examinations about patients who were older than 50 years of age and who were examined shortly after they presented with a recent clinical fracture, in order to prevent subsequent fractures. The results were reported by the FLSs in a standardised database.

FLS procedures

Several organisational aspects were examined: number of patients, inclusion and exclusion criteria, patient recruitment, fracture location, nurse time, performed examinations (CRFs, DXA, laboratory examinations, circumstances of injury) and results of CRFs and DXA. All fractures were categorised using ICD-9 classification (skull, spine, clavicle, thorax, pelvis, humerus, radius/ulna, hand, hip, femur, patella, tibia/fibula, ankle, foot, multiple, other) and classified as major (pelvis, vertebra, distal femur, proximal tibia, multiple ribs and proximal humerus), minor (all other excluding major fractures, hip and finger/toe fractures), hip and fingers/toes, according to Center et al. [6]. Fractures were also divided into hip, humerus, distal radius/ulna and tibia/fibula fractures. To evaluate all patients in the analysis, all remaining fractures were analysed as “other fractures”.

Statistical analysis

FLS characteristics were analysed with Pearson’s chi-square for dichotomous variables and independent-sample t test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables. Dichotomous variables were presented as percentages or mean with standard deviation (SD). Variability of the presence of CRFs between FLSs was calculated as relative risks (RR), i.e. as the relative difference between highest and lowest prevalence. A p value ≤ 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software 15.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., IL, USA).

Results

During a follow-up between 39 to 58 months, depending on the FLS, 7,199 patients over the age of 50 years were examined at the FLS (range, 847 to 2,224 per FLS) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of performance and procedures in the five FLSs

| FLS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent (number of patients) | 30.9% (n = 2,224) | 11.8% (n = 847) | 19.6% (n = 1,409) | 23.6% (n = 1,699) | 14.2% (n = 1,020) |

| Time period studied (months) | 47 months | 58 months | 52 months | 54 months | 39 months |

| Patients/month | 47 | 15 | 27 | 31 | 26 |

| Inclusion criteria | ≥50 years, all fracture types | ≥50 years, all fracture types | ≥50 years, all fracture types | ≥50 years, all fracture types | ≥50 years, all fracture types |

| Exclusion criteria | Dementia, pathological fracture | Dementia, HET | Dementia, pathological fracture HET | Dementia, pathological fracture HET | Dementia, pathological fracture |

| Patient recruitment | E-care system, ED, outpatient clinic, cast clinic | Outpatient clinic, cast clinic, E-care system, ED | Through radiology reports and thereafter contacted by phone | Through radiology reports and thereafter contacted by phone | ED nurse and in hospital patients via surgeon/orthopaedic surgeon |

| Fracture location unknown (%) | 3.3 | 4.5 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| Nurse practitioner | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Nurse | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time per week (hrs) | 7 × 4 | 4 × 4 | 2 × 8 | 2 × 8; 1 × 4 | 3 × 8 |

| Counselling | Trauma surgeon, orthopaedic surgeon, internist–rheumatologist | Internist–endocrinologist (by phone) | Internist–endocrinologist | Internist–endocrinologist | Internist, trauma surgeon |

| DXA scan | Yes after first visit | Yes before first visit | Yes before first visit | Yes before first visit | Yes before first visit |

| No DXA scan results (%) | 12.1 | 17.0 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 9.8 |

| Blood examination | Men | T-score <−2.0, osteoporosis | Men <65 years and T-score ≤−2.5; women/men <70 years and T-score ≤−3.0 | Men <65 years and T-score ≤−2.5; women/men <70 years and T-score ≤−3.0 | All patients |

| Questionnaire | Nurse | Patient | Patient | Patient | Nurse |

| CRFs missing (%) | |||||

| Previous fracture ≥50 years | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 |

| Previous vertebral fracture | 0 | 34.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Family history of hip fracture | 0 | 1.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Immobility | 0 | 48.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Low body weight (<60 kg) | 30.5 | 2.5 | 1.6 | 5.7 | 5.3 |

| Use of corticosteroids | 0 | 2.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fall risks missing (%) | |||||

| Fall in preceding 12 months | 0 | 56.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 100a |

| Fracture due to fall from standing height | 0 | 48.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

HET high energetic trauma; ED Emergency Department; BMD bone mineral density; DXA dual 2 energy X-ray absorptiometry

aOne FLS inquired into fall risk assessment with a different question

Implementation of the national osteoporosis guideline at the FLSs Performance

All five FLS took initiatives to implement the guideline on osteoporosis from 2002 onwards and had a dedicated nurse, of whom one had specialised training as a nurse practitioner (registered nurse with specific advanced nursing education) (Table 1). All FLSs reported to consider all patients older than 50 years with any fracture for examination. Exclusion criteria differed between FLSs; four excluded patients with pathological fractures and four with high energetic trauma (HET).

Counselling of the fracture nurse was performed by the trauma surgeon in two FLSs, by an endocrinologist in three or by a rheumatologist or general internist in one FLS.

Baseline characteristics (age, sex and CRFs) were screened during the visit at the FLSs by questionnaire before their visit to the FLS in three centres and by personal contact with the nurse in two centres. In three centres, the patient filled in the questionnaire and discussed this at the outpatient clinic, in two centres all questions were asked by the nurse.

CRFs were examined in all, but recording varied between FLSs. Whether patients had a history of fracture after the age of 50 years, a family history of hip fracture or used glucocorticoids was recorded in >97% of all patients. A history of vertebral fracture was asked for in all patients in four centres and in 65% of one centre. Low body weight was recorded as a CRF in >94% of patients in four centres and in 69% of patients in one centre. A fall during the past year was asked for in >99% of patients in three centres and in 44% in one centre. In one centre, the nurse inquired into previous falls in the preceding 6 months (data not shown). DXA examinations were performed in 83 up to >99% of patients. Criteria for laboratory examinations differed between FLSs: in all patients (n = 1), only in men (n = 1), in men younger than 65 years (n = 2), in patients with a T-score <−2.0 (n = 1), and in women depending on age and T-score (n = 2) (Table 1).

The acute circumstances of trauma were specified in all FLS, but extensively in four (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of CRFs, falls and circumstances of trauma in all patient cohorts and according to the different FLSs

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | All | RRa | P valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (SD) | 67.5 (10.7) | 69.0 (10.5) | 65.6 (9.3) | 65.4 (9.2) | 67.0 (10.2) | 66.7 (10.0) | <0.001 | |

| Sex (%) | <0.001 | |||||||

| • Women | 74.2 | 88.2 | 70.0 | 79.9 | 77.0 | 76.7 | ||

| • Men | 25.8 | 11.8 | 30.0 | 20.1 | 23.0 | 23.3 | ||

| Fracture location (%) | <0.001 | |||||||

| • Major | 18.1 | 15.3 | 13.4 | 14.6 | 14.8 | 15.5 | ||

| • Minor | 70.3 | 78.5 | 66.3 | 65.5 | 75.9 | 70.1 | ||

| • Hip | 5.5 | 5.3 | 7.6 | 7.3 | 1.0 | 5.7 | ||

| • Fingers/Toes | 6.1 | 0.9 | 12.6 | 12.6 | 8.4 | 8.7 | ||

| • Hip | 5.5 | 5.3 | 7.6 | 7.3 | 1.0 | 5.7 | ||

| • Humerus | 13.7 | 12.3 | 9.9 | 11.0 | 14.3 | 12.2 | ||

| • Distal radius/ulna | 25.8 | 22.4 | 26.8 | 26.9 | 27.2 | 26.1 | ||

| • Tibia/fibula | 12.7 | 12.8 | 13.3 | 12.7 | 12.8 | 12.9 | ||

| • Other | 42.3 | 47.1 | 42.4 | 42.1 | 44.7 | 43.2 | ||

| BMD (%) | <0.001 | |||||||

| • Normal BMD | 23.7 | 5.0 | 26.6 | 15.5 | 30.3 | 21.2 | ||

| • Osteopenia | 44.7 | 54.3 | 46.2 | 45.5 | 47.5 | 46.6 | ||

| • Osteoporosis | 31.6 | 40.7 | 27.2 | 39.0 | 22.2 | 32.2 | ||

| CRF (%) | ||||||||

| Previous fracture ≥ 50 years | 25.9 | 12.6 | 21.4 | 16.4 | 23.9 | 20.9 | 2.1 | <0.001 |

| Previous vertebral fracture | 6.8 | 9.6 | 6.0 | 5.8 | 9.3 | 7.0 | 1.7 | <0.001 |

| Family history of hip fracture | 15.4 | 7.3 | 8.9 | 18.6 | 26.9 | 15.6 | 3.7 | <0.001 |

| Immobility | 3.0 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 10.7 | 2.9 | 26.8 | <0.001 |

| Low body weight (<60 kg) | 19.0 | 17.0 | 13.1 | 13.8 | 8.6 | 14.4 | 2.2 | <0.001 |

| Use of corticosteroids | 0.7 | 7.4 | 0.2 | 1.6 | 5.0 | 2.2 | 37.0 | <0.001 |

| Fall risk (%) | ||||||||

| Fall in preceding 12 months | 20.5 | 21.8 | 3.7 | 14.4 | No datac | 14.1 | 5.9 | <0.001 |

| Fracture due to fall from standing height | 80.6 | 91.1 | 81.5 | 81.3 | 51.0 | 77.2 | 1.8 | <0.001 |

| Prevalence aetiology of the fracture (%) | ||||||||

| Accident at home | 28.2 | 58.4 | 31.5 | 34.9 | 42.8 | 34.7 | 2.1 | <0.001 |

| Accident at work | 1.6 | 0.2 | 1.4 | 2.0 | 2.6 | 1.7 | 10.0 | 0.021 |

| Fall accident | 80.6 | 91.1 | 81.5 | 81.3 | 51.0 | 77.2 | 5.9 | <0.001 |

| Traffic accident | 11.0 | 23.3 | 14.4 | 26.9 | 7.7 | 16.0 | 3.5 | <0.001 |

| Sport accident | 4.0 | 3.0 | 5.7 | 7.1 | 4.5 | 5.1 | 2.4 | <0.001 |

| Aetiology unknown | 4.7 | 8.0 | 3.8 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 3.6 | 5.0 | <0.001 |

| Aetiology other | 6.8 | 0.5 | 17.5 | 6.6 | 2.8 | 7.9 | 35.0 | <0.001 |

aRR is calculated as a ratio between the highest en the lowest prevalence of CRFs, fall risk and prevalence of aetiology of the fracture

b P value is calculated by using chi-square, Student’s t test and ANOVA and refers to a comparison between the five FLSs

cOne FLS inquired into fall risk assessment with a different question

Patient characteristics

Of the 7,199 patients, 76.7% were women. Mean age was 66.7 years (SD, 10.0).The number of patients included varied between 15 and 47/month/centre. The fracture nurse spends between 16 and 24 h/week at the FLS and therefore the time per patient varied between 0.9 and 1.7 h per patient. Data on fracture locations were only available for patients seen at the FLS. No records were available on patients who did not consult the FLS. The majority of examined patients sustained a distal radius/ulna fracture (n = 1,828, 26.1%). Hip and tibia/fibula fractures occurred in 397 (5.7%) and 900 (12.9%) patients, respectively and humerus fractures in 854 (12.2%). Most frequent fractures in women were radius/ulna fractures (n = 1,582; 29.5%), humerus fractures (n = 702; 13.1%) and fractures of the foot (n = 634; 11.8%) (Table 3). Men sustained primarily hand fractures (n = 264; 16.1%), radius/ulna fractures (n = 246; 15.0%) and foot fractures (n = 186; 11.3%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Frequencies of fracture according to gender

| Women | Men | All | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fracture sites (%) | <0.001 | |||

| • Major | 15.6 | 15.6 | 15.6 | |

| • Minor | 71.6 | 65.1 | 70.1 | |

| • Hip | 5.3 | 7.0 | 5.7 | |

| • Fingers/Toes | 7.6 | 12.3 | 8.7 | |

| <0.001 | ||||

| • Hip | 5.3 | 7.0 | 5.7 | |

| • Humerus | 13.1 | 9.3 | 12.2 | |

| • Distal radius/ulna | 29.5 | 15.0 | 26.1 | |

| • Tibia/fibula | 12.2 | 15.1 | 12.9 | |

| • Other | 40.0 | 53.6 | 43.2 |

Significant differences between FLSs were found for major fractures (13.4–18.1%), minor fractures (65.5–78.5%), hip fractures (1.0–7.6%) and fractures of fingers or toes (0.9–12.6%) (p < 0.001 between FLSs) (Table 2).

The acute circumstances of injury were extensively reported by four FLSs. Traumas occurred at home in 28.2% to 58.4% of patients and at work in 0.2% to 2.0%. An injury was reported to be a fall in 51.0% to 91.1%, a traffic accident in 11.0% to 26.9% and a sport injury in 3.0% to 7.1%. Overall, 77.2% of all fractures were caused by a fall (Table 2).

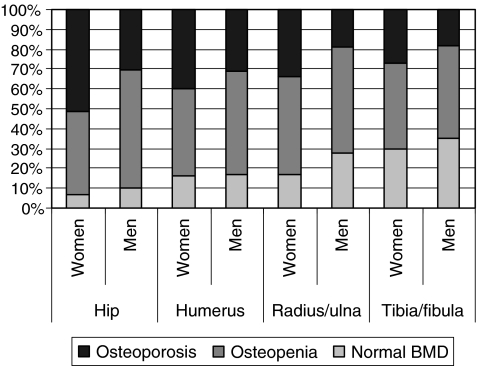

Prevalence

Significant differences were found in the prevalence of CRFs between FLSs (p < 0.001 for all CRFs). A history of fracture after the age of 50 years was reported by 12.6% to 25.9% of patients, a previous vertebral fracture in 5.8% to 9.6%, a family history of hip fracture by 7.3% to 26.9%, immobility by 0.4% to 10.7%, low body weight by 8.6% to 19.0%, use of glucocorticoids by 0.2% to 5.0% and a fall during 12 months before the current fracture by 3.7 to 21.8%. The majority of patients had osteopaenia (n = 3,107, 46.6%) and nearly one in three patients had osteoporosis (n = 2,147, 32.3%). More women than men were diagnosed with osteoporosis (35.2% vs. 22.9%; p < 0.001) or osteopaenia (45.9% vs. 48.5%; p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). Significant differences between FLSs were found in the prevalence of osteoporosis (in 22.2 to 40.7%), osteopaenia (in 44.7 to 54.3%) and normal BMD (in 5.0% to 30.3%) (p < 0.001).

Fig. 1.

Bone mineral density according to sex and fracture location. Only patients with hip, humerus, distal radius/ulna and tibia/fibula fractures are evaluated in this figure

Variability expressed as RR between the CRFs ranged from an RR of 1.7 to 37.0, depending on the risk factor, lowest variability in previous vertebral fracture (RR, 1.7), highest in use of corticosteroids (RR, 37.0) (Table 2).

Discussion

In this prospective study in patients older than 50 years presenting with a recent clinical fracture at five large FLSs in the Netherlands, a dedicated fracture nurse was the central responsible coordinator to identify fracture patients to evaluate risk factors for subsequent fractures and to organise secondary fracture prevention after counselling by the surgeon, endocrinologist or rheumatologist. Nearly 150 patients were examined per month resulting in nearly 7,200 evaluated patients during 250 months in total. This indicates that specialists in these hospitals made a major effort to implement the guidelines of the case finding of osteoporosis and fall prevention in daily practice.

The fracture nurse did spend 0.9 to 1.7 h per patient, indicating that organisation of post-fracture care is labour intensive. It should be further investigated which components of this work (such as patient contact, administrative tasks for appointments, reporting to the GP) are the most time consuming and how this time spending can be optimised.

Performance

Most CRFs that were mentioned in the questionnaire to the FLSs were recorded, with the exception previous vertebral fracture, immobility, low body weight and a fall in the preceding 12 months in one centre. Bone densitometry was performed in most patients. Reasons for not performing a DXA were not mentioned but is often the result of patients (or their family) who do not agree or not able to perform further examinations [17].

Criteria for laboratory investigations were highly variable between FLSs and were performed according to age, gender, and BMD as criteria. This variability can be the result of the lack of specific guidelines on the role of laboratory investigations in fracture patients [12]; however, several studies indicate that contributors to secondary osteoporosis are often present in patients with osteoporosis, with and without a history of recent fracture [19, 20]. Clearly, more data are necessary about the prevalence of contributors to secondary osteoporosis and bone loss in fracture patients with and without osteoporosis to specify which laboratory examinations should be performed.

The age and sex of patients and fracture location were significantly different between FLSs, but less significant from a clinical point of view (differences of 4.5 years for age, 5.7% for females, 4.7% for major fractures), indicating that patient selection was quite similar between FLSs.

Of interest is the finding that most fractures resulted from a fall (77.2%) and a minority as a result of a traffic or sport accident, as found by others [20]. In spite of the exclusion of HET, 11% to 27% of traffic accidents were still interpreted as a low-energy trauma. There is a need to specify which traumas are considered minor or major. On the one hand, the definition of ‘fragility’ or ‘osteoporotic’ fractures is heterogeneous in the literature [21]. On the other hand, however, high-energy trauma fractures are as predictive for subsequent fracture risk as low-trauma fractures [22]. In addition, a 5-year subsequent fracture risk is similar after a finger or hip fracture but a 5-year mortality is different, being higher after a hip fracture than after a finger fracture [10]. Thus, in the context of case findings of subsequent fracture risk in patients with a recent fracture, there is presumably no need for distinction between high- and low-energy fractures and fracture locations.

Prevalence

There was a high variability in the reporting of several CRFs between FLSs. The reason for this is unclear. For example for immobility, the variance between centres was very high and could reflect the absence of a clear definition of this CRF in the guideline [12]. Clearly, to prevent confusion about definitions in daily practice, risk factors should be specified as concrete as possible in guidelines.

Differences between FLSs were also found in T-scores and fall risks of the included patients per centre. In our study, the range of prevalence of osteoporosis was 22.2% to 40.7% between centres and for fall risk (fracture due to fall from standing height or less) 51.0% to 91.1%. Presumably, not all centres had the same interest of formally evaluating fall risk or did not include such evaluation in their protocol, in spite of a guideline on fall prevention in the Netherlands.

Recent literature on fracture prevention focuses more on a combination of bone and extraskeletal risks in fracture patients [7]. This is also expressed in the FRAX tool, which predicts future fractures based on several CRFs with and without BMD and in the Garvan fracture risk calculator, which also includes fall risk [11, 23].

This study has several limitations. Firstly, there are no data on all patients who visited the hospitals due to a fracture and did not visit the FLS. We only have data on subjects who were able and willing to undergo evaluation of their fracture risk, and we cannot give a percentage of the patients who were willing or not willing to participate; however, from previous studies, it is known that 50–85% of the patients at high risk for an osteoporotic fracture participate in osteoporosis assessment [13–15, 24]. Secondly, there is no information about the ethnicity of the participants. Thirdly, we do not have data on subsequent fractures of these patients. It would be very informative to determine in a cohort of treated fracture patients and see whether there is an association between CRFs, BMD and fall risks on subsequent fractures and mortality. Possibly, as seen in this study, not all risk factors are evenly distributed throughout the fractured patients. Fourthly, almost 6% of all fractures were hip fractures compared to approximately 18–21% in other studies. It is possible that our data are not representative for hip fracture patients [9, 12].

In conclusion, when evaluating five FLSs in the Netherlands we found that there was a striking difference in prevalence of CRFs and fall risks between elderly screened for osteoporosis. Moreover, the study also showed that osteoporosis care in the Netherlands is implemented in several hospitals.

This indicates that prevention strategies to avert subsequent fractures mainly have to focus on BMD, CRFs and fall risks, and potentially there are differences in the presence of risk factors between different fracture types.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Bliuc D, Ong CR, Eisman JA, Center JR. Barriers to effective management of osteoporosis in moderate and minimal trauma fractures: a prospective study. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:977–982. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1788-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanis JA. Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis: synopsis of a WHO report. WHO Study Group. Osteoporos Int. 1994;4:368–381. doi: 10.1007/BF01622200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanis JA. Diagnosis of osteoporosis and assessment of fracture risk. Lancet. 2002;359:1929–1936. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08761-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanis JA, Johnell O, De Laet C, Johansson H, Oden A, Delmas P, Eisman J, Fujiwara S, Garnero P, Kroger H, McCloskey EV, Mellstrom D, Melton LJ, Pols H, Reeve J, Silman A, Tenenhouse A. A meta-analysis of previous fracture and subsequent fracture risk. Bone. 2004;35:375–382. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klotzbuecher CM, Ross PD, Landsman PB, Abbott TA, 3rd, Berger M. Patients with prior fractures have an increased risk of future fractures: a summary of the literature and statistical synthesis. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:721–739. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.4.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Center JR, Bliuc D, Nguyen TV, Eisman JA. Risk of subsequent fracture after low-trauma fracture in men and women. Jama. 2007;297:387–394. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bliuc D, Nguyen ND, Milch VE, Nguyen TV, Eisman JA, Center JR. Mortality risk associated with low-trauma osteoporotic fracture and subsequent fracture in men and women. Jama. 2009;301:513–521. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryg J, Rejnmark L, Overgaard S, Brixen K, Vestergaard P. Hip fracture patients at risk of second hip fracture-a nationwide population-based cohort study of 169, 145 cases during 1977–2001. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:1299–1307. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Helden S, Cals J, Kessels F, Brink P, Dinant GJ, Geusens P. Risk of new clinical fractures within 2 years following a fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:348–354. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-2026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huntjens KM, Kosar S, van Geel TA, Geusens PP, Willems P, Kessels A, Winkens B, Brink P, van Helden S (2010) Risk of subsequent fracture and mortality within 5 years after a non-vertebral fracture. Osteoporos Int (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Kanis JA World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Metabolic Bone Diseases UoS, UK FRAX; WHO Fracture Risk Assessment Tool http://www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/. 25-10-2010

- 12.CBO KvdG Osteoporose, tweede herziene richtlijn http://www.cbo.nl/thema/Richtlijnen/Overzicht-richtlijnen/Bewegingsapparaat/. 25-10-2010

- 13.McLellan AR, Gallacher SJ, Fraser M, McQuillian C. The fracture liaison service: success of a program for the evaluation and management of patients with osteoporotic fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14:1028–1034. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1507-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blonk MC, Erdtsieck RJ, Wernekinck MG, Schoon EJ. The fracture and osteoporosis clinic: 1-year results and 3-month compliance. Bone. 2007;40:1643–1649. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hegeman JH, Willemsen G, van Nieuwpoort J, Kreeftenberg HG, van der Veer E, Slaets JP, ten Duis HJ. Effective tracing of osteoporosis at a fracture and osteoporosis clinic in Groningen; an analysis of the first 100 patients. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2004;148:2180–2185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chevalley T, Hoffmeyer P, Bonjour JP, Rizzoli R. An osteoporosis clinical pathway for the medical management of patients with low-trauma fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2002;13:450–455. doi: 10.1007/s001980200053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Helden S, van Geel AC, Geusens PP, Kessels A, Nieuwenhuijzen Kruseman AC, Brink PR. Bone and fall-related fracture risks in women and men with a recent clinical fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:241–248. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Helden S, Cauberg E, Geusens P, Winkes B, van der Weijden T, Brink P. The fracture and osteoporosis outpatient clinic: an effective strategy for improving implementation of an osteoporosis guideline. J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13:801–805. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2007.00784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tannenbaum C, Clark J, Schwartzman K, Wallenstein S, Lapinski R, Meier D, Luckey M. Yield of laboratory testing to identify secondary contributors to osteoporosis in otherwise healthy women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:4431–4437. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dumitrescu B, van Helden S, ten Broeke R, Nieuwenhuijzen-Kruseman A, Wyers C, Udrea G, van der Linden S, Geusens P. Evaluation of patients with a recent clinical fracture and osteoporosis, a multidisciplinary approach. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:109. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sebba A. Comparing non-vertebral fracture risk reduction with osteoporosis therapies: looking beneath the surface. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:675–686. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0802-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mackey DC, Lui LY, Cawthon PM, Bauer DC, Nevitt MC, Cauley JA, Hillier TA, Lewis CE, Barrett-Connor E, Cummings SR. High-trauma fractures and low bone mineral density in older women and men. Jama. 2007;298:2381–2388. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.20.2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garvan Institute Fracture Risk Calculator. http://www.garvan.org.au/promotions/bone-fracture-risk/. 25-10-2010

- 24.Murray AW, McQuillan C, Kennon B, Gallacher SJ. Osteoporosis risk assessment and treatment intervention after hip or shoulder fracture. A comparison of two centres in the United Kingdom. Injury. 2005;36:1080–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]