Abstract

Background

Every year, 60 000 women in Germany are found to have breast cancer, and 9000 to have ovarian cancer. Familial clustering of carcinoma is seen in about 20% of cases.

Methods

We selectively review relevant articles published up to December 2010 that were retrieved by a search in PubMed, and we also discuss findings from the experience of the German Consortium for Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer.

Results

High risk is conferred by the highly penetrant BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes as well as by other genes such as RAD51C. Genes for breast cancer that were originally designated as moderately penetrant display higher penetrance than previously thought in families with a hereditary predisposition. The role these genes play in DNA repair is thought to explain why tumors associated with them are sensitive to platin derivatives and PARP inhibitors. In carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2, prophylactic bilateral mastectomy and adnexectomy significantly lowers the incidence of breast and ovarian cancer. Moreover, prophylactic adnexectomy also lowers the breast-and-ovarian-cancer-specific mortality, as well as the overall mortality. If a woman bearing a mutation develops cancer in one breast, her risk of developing cancer in the other breast depends on the particular gene that is mutated and on her age at the onset of disease.

Conclusion

About half of all monogenically determined carcinomas of the breast and ovary are due to a mutation in one or the other of the highly penetrant BRCA genes (BRCA1 and BRCA2). Women carrying a mutated gene have an 80% to 90% chance of developing breast cancer and a 20% to 50% chance of developing ovarian cancer. Other predisposing genes for breast and ovarian cancer have been identified. Clinicians should develop and implement evidence-based treatments on the basis of these new findings.

In Germany, breast cancer is the most common malignant disease in women and ovarian cancer the gynecological tumor with the highest mortality rate (e1). There may be a hereditary cancer burden even if only two or more women, or one young woman, in a family develop the disease (Table 1). Current work has shown that this may be caused by a monogenic or polygenic inheritance in which DNA repair genes are mutated (1). As yet there are no differences between the treatments provided for sporadic and hereditary breast and ovarian cancer, although there are indications that targeted therapy is effective in women with BRCA1/BRCA2-associated tumors (2, 3). Retrospective studies reveal a high level of sensitivity to platin derivatives in BRCA-associated tumors (4), and initial clinical trials show good efficacy and tolerability for PARPs, or poly ADP (adenosine diphosphate)-ribose polymerase inhibitors, in mutation carriers with advanced breast and ovarian cancers (5, 6). As PARPs are particularly effective on the tumor cells of mutation carriers, they might also potentially be used in chemoprevention. Thanks to multimodal screening, breast cancer in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers can be diagnosed at an early stage (7, e2). The selection of optimum examination methods and intervals and their possible effects on mortality are the subjects of ongoing studies. As yet there is no efficient screening for ovarian cancer (e3). However, the benefits of risk-reducing prophylactic surgery in mutation carriers have been confirmed (8). The German Consortium for Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer (Deutsches Konsortium für Familiären Brust- und Eierstockkrebs) has centers in 12 universities throughout Germany (http://www.krebsgesellschaft.de/onkoscout_zentren_familie_brustkrebs,85319.html—in German) (eBox 1) and aims to provide structured, validated genetic diagnostics and the resulting diagnostic and therapeutic interventions in gynecological oncology, via a multidisciplinary approach. This is possible not least thanks to central recording of inclusion criteria relating to patients’ medical histories for genetic testing (eBox 2) and of genetic, histological, clinical, and follow-up data in the Consortium’s central database at the University of Leipzig (Institute for Medical Computing, Statistics and Epidemiology [Institut für Medizinische Informatik, Statistik und Epidemiologie, IMISE]).

Table 1. Family constellations and empirical probability of pathogenic BRCA gene mutations (percentage of index patients with evidence of a pathogenic mutation, by family constellation; accuracy ±2%).

| Constellation | Empirical probability of mutation |

| ≥ 3 BC, 2 of them before | 30.7% |

| the age of 51 | |

| No OC, no male BC | |

| ≥ 3 BC at any age | 22.4% |

| No OC, no male BC | |

| 2 BC, both before the age of 51 | 19.3% |

| No OC, no male BC | |

| 2 BC, 1 of them before the age of 51 | 9.2% |

| No OC, no male BC | |

| ≥ 1 BC, ≥ 1 OC at any age | 48.4% |

| No male BC | |

| ≥ 2 OC at any age | 45.0% |

| No female or male BC | |

| 1 BC before the age of 36 | 10.1% |

| No OC, no male BC | |

| 1 bilateral BC, the 1st before the age of 51 | 24.8% |

| No OC, no male BC | |

| ≥ 1 male BC & ≥ 1 | 42.1% |

| female BC or OC |

BC, breast cancer; OC, ovarian cancerSource: German Consortium for Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer, 2011

ebox 1. List of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer centers in Germany.

Berlin

Charité, Berlin University Clinic

Center representative: Prof. Dr. Ulrich Bick

Cologne/Bonn

Cologne University Clinic

Center representative: Prof. Dr. Rita Schmutzler

Dresden

University Clinic, Dresden University of Technology

Center representative: Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Distler

Düsseldorf

Düsseldorf University Clinic

Center representatives: Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Janni, Dr. Dieter Niederacher

Hannover

Hannover Medical School (MHH)

Center representative: Prof. Dr. Brigitte Schlegelberger

Heidelberg

Heidelberg University Clinic

Center representative: Prof. Dr. Claus R. Bartram

Kiel

Kiel University Clinic

Center representatives: Prof. Dr. Walter Jonat,

Prof. Dr. Norbert Arnold

Leipzig

Leipzig University Clinic

Center representative: Dr. med. Briest

Munich

University Clinic, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich

Center representative: Prof. Dr. Alfons Meindl

Münster

Münster University Clinic

Project Manager: Prof. Dr. Peter Wieacker

Ulm

Ulm University Clinic

Center representative: Prof. Dr. Rolf Kreienberg

Würzburg

Würzburg University Clinic

Project Manager: Prof. Dr. Tiemo Grimm

ebox 2. Criteria for genetic analysis of breast cancer genes BRCA1 and BRCA2 with one index person in the family (S3 guideline, 2008).

Breast or ovarian cancer in at least two family members, at least one first diagnosed before the age of 51

Breast cancer in at least three family members, first diagnosed at any age

Breast cancer in one family member aged 36 or younger

Bilateral breast cancer in one family member aged 51 or younger

Breast and ovarian cancer in one or more family members

Breast cancer in one male family member and breast or ovarian cancer in one female family member

Genetic diagnostics

Monogenic inheritance of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations

Hereditary breast and ovarian cancers are caused by an autosomal dominant inheritance with incomplete penetrance. Population-based studies put its penetrance for breast cancer at 45% to 65% (e4, e5). In family-based research involving families with many cases of these diseases, however, these figures are higher (9). This points to the effect of modifying factors and lifestyle. Sometimes there may be a genetic defect with no disease burden in the family’s medical history. This is due to the low penetrance in male BRCA1/2 mutation carriers (around 5% for breast cancer), referred to as the gender effect.

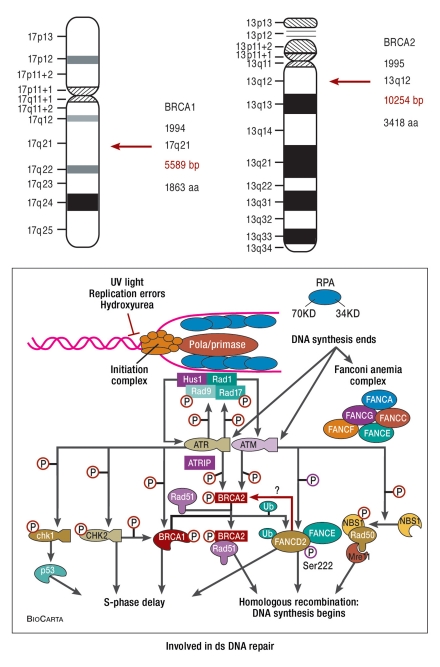

The two genes most commonly mutated in hereditary breast and ovarian cancer are the tumor suppressor genes BRCA1 and BRCA2 (Figure 1). They are mutated in approximately 25% of hereditary breast cancers and 5% of all breast cancers. They are key genes in DNA repair and are passed on to 50% of descendants as mutated alleles in a monogenic inheritance. The probability of a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation depends on certain familial constellations, such as frequency of disease, age at onset of disease, and the organs affected (breast, ovary) (Table 1). Within the German Consortium, a 10% empirical probability (upper limit of confidence interval) of evidence of mutation is currently the inclusion criterion for genetic testing. This figure may change as a result of new, inexpensive testing methods such as massively parallel sequencing (1) and the increasing relevance of evidence of mutations to treatment. It should therefore be established in a transparent, traceable, standardized decision-making process (3, e6).

Figure 1.

Tumor suppressor genes BRCA1 and BRCA2 (from: Levy-Lahad, Nature Genetic 2010; 5: 368)

As part of predictive BRCA diagnostics, i.e. analysis of mutations in healthy women who consult a doctor and whose families have demonstrated pathogenic BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations, in 50% of these women the mutation can be ruled out and the individuals reassured. However, if a mutation is detected, various preventive measures can be offered, including participation in multimodal screening and prophylactic surgery. If no mutation is found in the family of someone who has developed the disease, predictive testing is not possible (non-informative gene test). In these cases, the statistical risk of the person who has consulted is calculated on the basis of her family’s medical history. There is a high to moderate risk if there is a remaining lifetime risk of developing breast or ovarian cancer of at least 30% or a risk of an as yet unidentified mutation of at least 20%, calculated according to a validated risk calculation model (Cyrillic 2.1, www.cyrillicsoftware.com). Screening is also recommended for these women.

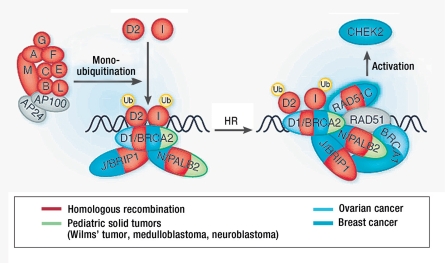

Monogenic inheritance in mutations of the gene RAD51C and as yet unidentified, highly penetrant genes

The third highly penetrant gene for breast and ovarian cancer was successfully identified in the summer of 2010 (10). The identified gene, RAD51C, is mutated in approximately 1.5% to 4% of all families predisposed towards breast and ovarian cancer, with high or moderate penetrance. Like BRCA1 and BRCA2, it plays a central role in DNA repair as a tumor suppressor gene (Figure 2). This important cellular function is also reflected in its high level of evolutionary preservation (10). Preliminary studies in other populations confirm that RAD51C is a predisposing gene (Trinidad Caldes, San Carlos Hospital, Madrid, Spain: personal communication). However, as it is seldom mutated and the data available on its penetrance are as yet insufficient, it is currently not offered as part of routine diagnostics. However, the German Consortium’s centers do offer testing to appropriate families as part of a prospective clinical validation study.

Figure 2.

RAD51C: a new predisposing gene for breast and ovarian cancer (dominant) and Fanconi anemia (recessive) (from: Levy-Lahad, Nature Genetics 2010; 5: 368)

Moderately and mildly penetrant gene variants

Although a significant proportion of BRCA1/2-negative high-risk families are likely to have mutations in highly penetrant genes which have not yet been identified, the combined effect of moderately and mildly penetrant gene variants is probably responsible for the majority of carcinomas (11, e7). This may be true of 50% of cases of hereditary breast cancer and 20% of all cases of breast cancer (Table 2). By way of examples, ATM, CHEK2, BRIP1, and PALB2 have been identified as moderate-risk genes with low heterozygote frequency (11, e7). Like the high-risk genes described above, they also play a role in DNA repair. Preliminary data from the population as a whole indicate that mutations in the gene CHEK2 increase the risk of breast cancer two- to three-fold (e8), and four- to five-fold when there is a familial burden (12). This supports the hypothesis that the penetrance of CHEK2 mutations in high-risk families is modified by other genetic alterations and/or environmental factors: a multifactorial inheritance. In the German population, CHEK2 is mutated in around 4% of all cases of hereditary breast cancer; half of these are caused by a particular founder mutation (e9). The mutation frequency of PALB2, another DNA repair gene, has also been determined in families predisposed towards breast cancer. The prevalence of mutations in the populations of both Germany and England is approximately 1% (Hellebrand et al., Hum Mut, in print) (e10), indicating that the moderately penetrant genes which have yet to be identified are also rarely mutated.

Table 2. The effects of breast cancer genes on risk.

| Risk genes | Increase in risk | Genes/syndromes |

| Highly penetrant genes | 5- to 20-fold | BRCA1/BRCA2/RAD51C: hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome TP53: Li-Fraumeni syndrome STK11/LKB1: Peutz-Jeghers syndrome PTEN: Cowden syndrome |

| Moderately penetrant genes | 1.5- to 5-fold | CHEK2, PALB2, BRIP1, ATM |

| Mildly penetrant genes | 0.7- to 1.5-fold | FGFR2, TOX3, MAP3K1, CAMK1D, SNRPB, FAM84B/c-MYC, COX11, LSP1, CASP8, ESR1, ANKLE1, MERIT40, etc. |

On the basis of the hypothesis of a multifactorial inheritance that includes synergy between several low-risk variants, moderate gene mutations, and environmental factors, genome-wide correlation analysis was performed to identify new locations of risk genes (13, e11). Several low-risk variants located within the intron, specifically DNA segments that do not code for proteins, or regulatory areas, were identified in the following genes: FGFR2, TNRC9, MAP3K1, LSP1 (2q35, 6q22.33, 8q24) (11, 13). The risks inherent in these variants are very low, with relative risks (RRs) of approximately 1.1 to 1.3, but their heterozygote frequencies are high. Thus around 40% of the German population carries an FGFR2 risk allele, for example, leading to a relative risk of disease of only 1.2. Low-risk variants of the genes FGFR2, TOX3, and LSP1 were also shown to have a greater effect in high-risk families than in sporadic cases. This points to a higher number of other risk factors in high-risk families, a multifactorial inheritance (e12, e13). However, with no knowledge of other modifying or interacting factors the clinical benefit of obtaining evidence of such risk variants is slight. Testing is therefore not currently indicated.

Modulation of the risk of disease in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers

Nevertheless, such low-risk variants can also affect the onset of breast or ovarian cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. For example, a BRCA2 mutation carrier’s actual age at onset of disease is affected by the low-risk variant of the gene FGFR2 (14), and BRCA1 mutation carriers’ disease risk is partly determined by a low-risk variant of the gene MERIT40 (e14). The first modifier that modulates the risk of ovarian cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers was also identified in this group (e15). Here again, further research is needed into the synergies which lead to clinically significant risk increases.

Clinical care

Clinical features of BRCA1/2-associated breast cancers

Mutation carriers’ age at onset of disease of is some 20 years below that of women with sporadic breast cancer, ranging from patients’ teens to their seventies. BRCA1-associated breast cancers are similar to sporadic, triple-negative cancers (e16). Tumors proliferate aggressively, metastasize mainly in the three years following diagnosis, and show a weak correlation between tumor size, lymph node status, and survival (e17). The 10-year survival rates for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers, however, are similar to those of women with sporadic breast cancer (e18).

Morphological features of BRCA1/2-associated breast cancers

BRCA1-associated breast cancers can be distinguished unambiguously from carcinomas of BRCA2 mutation carriers and age-adjusted controls with no hereditary risk, on the basis of their morphological, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic features (15, e19, e20). Such unambiguous differentiation is not possible for BRCA2 and non-BRCA1/2 breast cancers (15).

High risk of secondary cancer

The risk of contralateral breast cancer depends on age at onset of disease and on which BRCA gene is affected. On the basis of 2020 patients from families with BRCA1/2 mutations, the German Consortium showed that the cumulative risk of disease for the healthy breast was 47.4% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 38.8% to 56.0%) (16). Women from BRCA1-positive families have a risk of developing contralateral cancer 1.6 times higher than that of women from BRCA2-positive families. Young age at onset of disease is also associated with a higher risk of secondary disease (16). Mutation carriers have no increased risk of ipsilateral recurrence following breast-preserving surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy (e21). Limited data on just under 400 patients from BRCA1/2-negative high-risk families were unable to prove a substantial increase in the risk of contralateral breast cancer in comparison to patients with sporadic breast cancer (e22). A comprehensive evaluation of the German Consortium’s data is therefore currently in progress, with the aim of resolving once and for all the clinically important question of whether contralateral mastectomy should be indicated for BRCA1/2-negative high-risk patients.

Prophylactic surgery

Risk-reducing surgery available to mutation carriers includes prophylactic bilateral mastectomy (PBM), prophylactic contralateral mastectomy (PCM), and prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (PBSO) (Table 3). PBM reduces the risk of developing breast cancer by more than 95% and in consequence reduces breast cancer-specific mortality by 90% (17, e23, e24). PBM should not be performed before the age of 25 (e6). As stated above, PCM must be preceded by risk calculation, reflecting the affected gene, age at onset of disease in patients with a history of unilateral cancer, and prognosis after onset of disease (16). It is essential to discuss immediate heterologous and autologous reconstruction in consultations before surgery.

Table 3. Prophylactic surgery recommended for high-risk women who are healthy and those with a history of unilateral breast cancer, with and without BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations*1.

| BRCA mutation status | Personal medical history | Prophylactic mastectomy | Prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy |

| Positive | Healthy | As patient wishes, from age of 25 onwards*2 | Indicated, should be expressly recommended; from age of 40 onwards*2 |

| Unilateral breast cancer | Possible, particularly for young patients, depending on gene affected, age at onset of disease, and prognosis | To be recommended according to prognosis | |

| Negative | Unilateral breast cancer | Not generally indicated; may be considered only in individual cases, depending on prognosis and individual risk (insufficient data) | Not generally indicated; may be considered only in individual cases when there is ovarian cancer in the family |

| Healthy | Not generally indicated; may be considered only in individual cases with high statistical risk of disease (insufficient data) | Not generally indicated; may be considered only in individual cases when there is ovarian cancer in the family |

*1for RAD51C phenotypic testing for tumor subtype and clinical disease progression are also required;

*2 or five years below the youngest age at onset of disease in other family members

PBSO reduces the risk of ovarian cancer by 97%. It also reduces the risk of breast cancer by 50% (18) and the risk of contralateral secondary cancer by 30% to 50% (e21). A 75% decrease in overall mortality has also been demonstrated for PBSO (8, e24). Laparoscopic PBSO is recommended at approximately 40 years of age and after family planning has been completed (e6). Hormone replacement therapy is indicated up to the age of approximately 50.

Risks of associated carcinomas

Studies have indicated that in addition to an increased risk of breast and ovarian cancer, germline mutations in the BRCA genes also increase the overall risk of cancer (19, e25).

BRCA2 mutations increase the risk of prostate cancer up to seven-fold in carriers under the age of 65; BRCA1 mutations increase the risk up to two-fold (19, e26). A preliminary evaluation of the international prostate screening study IMPACT (Identification of Men With a Genetic Predisposition to ProstAte Cancer) is available. In the study, BRCA1/2 mutation carriers aged between 40 and 69 were offered annual PSA analysis and a prostate biopsy if their PSA value was higher than 3 ng/mL. The study shows a high positive predictive value (47.6%) for PSA screening and a significantly higher rate of detection of prostate cancer in mutation carriers than in men with no mutations (20).

The methods and populations involved in studies of BRCA-associated colon cancer are very varied. In patients from families with BRCA mutations, some of whom were unaware of their mutation status, a risk increase of 2.5 to 4 (95% CI, 1.02 to 6.3 and 2.36 to 7.15) was described (e27). No special screening measures are as yet indicated on the strength of these limited data.

Approximately 10% of pancreatic cancers are classified as hereditary (e28). A study by the Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium (BCLC) yielded a figure of 2.26 for the relative risk (RR) of female BRCA1 mutation carriers and 3.55 for that of female BRCA2 mutation carriers (19). The risk may also be significantly increased for mutations of the genes CHEK2 and PALB2, which like BRCA2 may be altered in families predisposed towards pancreatic cancer (e29, e30). Preliminary studies show a good response by BRCA2-deficient pancreatic cancer cells to PARP inhibitors (e31), and synergy between gemcitabine and PARP inhibitors against BRCA2-associated pancreatic cancers in an animal model (21).

Salpingo-oophorectomy is particularly recommended for BRCA1/2 mutation carriers, because the risks of disease concern not only the ovaries but also the fallopian tubes (e32).

Structured screening

Because of patients’ young age at onset of disease, screening must begin before the age at which screening mammograms are recommended for the female population as a whole (from 50 onwards). The higher density of the breast tissue of young women from high-risk families, the specific tumor morphology, and the high tumor proliferation rate in the high-risk population must also be taken into account when selecting examination methods and intervals in the multimodal screening program at the Consortium’s centers (e33) (Box). Multimodal screening should include an MRI of the breast, as this is the most sensitive examination method, annually between the ages of 25 and 55 (22, 23, e34, e35). Knowledge of specific benign tumor morphology in imaging procedures (e36) can increase sensitivity, especially that of annual mammograms from the age of 30 onwards and twice-yearly ultrasound scans of the breasts (e37). Ongoing studies aim to investigate the effect of early diagnosis on mortality and quality of life.

Box. Intensive screening program.

Breast palpation by doctor every 6 months*1

Breast ultrasound every 6 months*1

Mammogram every 12 months*2

Breast MRI every 12 months (at appropriate points in menstrual cycle in premenopausal women!)*1 and *3

*1 From the age of 25 onwards, or five years below the youngest age at onset of disease in the family

*2 From the age of 30 onwards, or from 35 if breast tissue is dense

*3 MRI generally recommended only up to the age of 55 or until involution of breast parenchyma (ACRI-II)

Platin sensitivity of BRCA-associated carcinomas

Several preclinical trials indicate resistance of BRCA-incompetent cells to spindle poisons such as vinca alkaloids and taxanes (24, e38) and increased sensitivity of BRCA-associated carcinomas to DNA-intercalators such as platin derivatives (4). On the strength of low remission rates, a prospective randomized trial in England is currently in its recruitment phase and will assess the efficacy of carboplatin versus docetaxel in first- or second-line therapy for metastatic breast cancer in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers (BRCA trial UK homepage: http://www.breakthroughresearch.org.uk/clinical_trials/the_brca_trial.html).

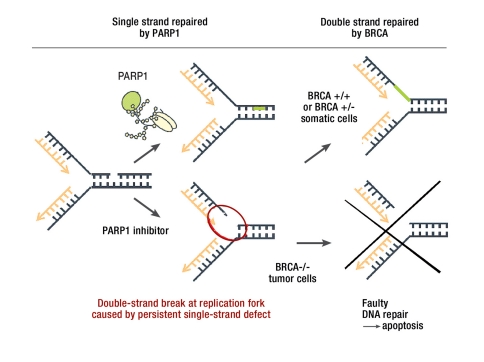

PARP inhibitors and BRCA tumors

Research on BRCA-deficient cell lines heralded the beginning of the clinical use of a previously little-known group of substances, PARP inhibitors (Figure 3) (2, e39). The proof of principle for this theory, which was developed on the basis of in vitro tests, has already been performed in two similarly-designed Phase II trials (3, 5, 6). The efficacy of monotherapy using the PARP inhibitor AZD2281 for breast and ovarian cancer patients with pathogenic BRCA mutation who had already received multiple prior treatments was demonstrated, with a response rate of approximately 40% over an average of six months. This makes PARP inhibitors by far the most promising targeted substances since the introduction of trastuzumab for HER2/neu-overexpressing breast cancer. Another international Phase II trial of the PARP inhibitor AZD2281 began in October 2010 (led by Prof. Schmutzler, Cologne). To date, molecular genetic analysis of the breast cancer genes BRCA1 and BRCA2 is the best predictive parameter for response to PARP inhibitor treatment (25).

Figure 3.

Damage to single strand and double strand of DNA with repair by proteins PARP1 and BRCA: a single-strand defect is repaired by PARP1. If PARP1 is inhibited, a persistent single-strand defect results in a double-strand break at the replication fork the next time the cell divides. The double-strand break is repaired by BRCA. In BRCA-incompetent tumor cells, however, the defect cannot be compensated for by double-strand repair and leads to apoptosis (from: Helleday et al.: Cell Cycle 2005; 4: 1776–8).

Key Messages.

Approximately 5% to 10% of all breast cancers are monogenic in origin.

If there is a familial burden, consultation should take place in a specialized, interdisciplinary center, of which 12 exist in Germany.

If BRCA1 or BRCA2 is mutated, there is a breast cancer risk of up to 85% and an ovarian cancer risk of up to 50%.

Intensive risk-adjusted screening is indicated if there is evidence of a mutation or a high-risk constellation (heterozygote risk >20% or lifetime risk >30%).

Risk can be reduced by prophylactic surgery. In the future drug-based prophylaxis may be possible.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Caroline Devitt, MA.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

PD Rhiem has received fees as members of the Advisory Board from Astra Zeneca.

Dr. Kast has received cost reimbursement and lecture fees from Roche Pharma, Essex Pharma, Sanofi Aventis, GlaxoSmithKline, Amgen, and Novartis.

Dr. Ditsch receives cost reimbursement from Sanofi-Aventis.

Prof. Dr. Meindl has received fees as members of the Advisory Board from Astra Zeneca.

Prof. Schmutzler has acted as an adviser to Astra Zeneca. He has received participation fees for the ASCO Congress from Astra Zeneca, Roche, Sanofi Aventis, and Glaxo; lecture fees from Astra Zeneca, Sanofi Aventis, and Roche; fees for clinical trials commissioned by Astra Zeneca, Sanofi Aventis, Siemens Medical Solutions, and Amgen; and payment for research projects from Siemens Medical Solutions.

References

- 1.Walsh T, Lee MK, Casadei S, et al. Detection of inherited mutations for breast and ovarian cancer using genomic capture and massively parallel sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:12629–12633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007983107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature. 2005;434:917–921. doi: 10.1038/nature03445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fong PC, Boss DS, Yap TA, et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polyme-rase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:123–134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Byrski T, Gronwald J, Huzarski T, et al. Pathologic complete response rates in young women with BRCA1-positive breast cancers after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:375–379. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.7019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Audeh MW, Carmichael J, Penson RT, et al. Oral poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor olaparib in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and recurrent ovarian cancer: a proof-of-concept trial. Lancet. 2010;24(376):245–251. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60893-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tutt A, Robson M, Garber JE, Domchek SM, et al. Oral poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor olaparib in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and advanced breast cancer: a proof-of-concept trial. Lancet. 2010;24(376):235–244. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60892-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warner E, et al. A prospective study of breast cancer incidence and stage distribution in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation under surveillance with and without magnetic resonance imaging. J Clin Oncol. 2011 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.0835. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Domchek SM, Friebel TM, Singer CF, et al. Association of risk-reducing surgery in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers with cancer risk and mortality. JAMA. 2010;304:967–975. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.King MC, Marks JH, Mandell JB. Breast and ovarian cancer risks due to inherited mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. Science. 2003;302:643–646. doi: 10.1126/science.1088759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meindl A, Hellebrand H, Wiek C, et al. Germline mutations in breast and ovarian cancer pedigrees establish RAD51C as a human cancer susceptibility gene. Nat Genet. 2010;42:410–414. doi: 10.1038/ng.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turnbull C, Rahman N. Genetic predisposition to breast cancer: past, present, and future. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2008;9:321–345. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.9.081307.164339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weischer M, Bojesen SE, Ellervik C, Tyboerg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG. CHEK2*1100delC genotyping for clinical assessment of breast cancer risk: meta-analyses of 26,000 patient cases and 27,000 controls. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:542–548. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.5922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Easton DF, Pooley KA, Dunning AM, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies novel breast cancer susceptibility loci. Nature. 2007;447:1087–1093. doi: 10.1038/nature05887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Antoniou AC, Spurdle AB, Sinilnikova OM, et al. Common breast cancer-predisposition alleles are associated with breast cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:937–948. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foulkes WD, Stefansson IM, Chappuis PO, et al. Germline BRCA1 mutations and a basal epithelial phenotype in breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1482–1485. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graeser MK, Engel Ch, Rhiem K, et al. Contralateral breast cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.9430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meijers-Heijboer H, van Geel B, van Putten WL, et al. Breast cancer after prophylactic bilateral mastectomy in women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:159–164. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107193450301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kauff ND, Domchek SM, Friebel TM, et al. Risk reducing Salpingo-oophorectomy for the prevention of BRCA1- and BRCA2-associated Breast and Gynecologic Cancer: A multicenter, prospective Study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1331–1337. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.9626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liede A, Karlan BY, Narod SA. Cancer risks for male carriers of germline mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:735–742. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitra AV, Bancroft EK, Barbachano Y, et al. Targeted prostate cancer screening in men with mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 detects agressive prostate cancer: preliminary analysis of the results of the IMPACT study. BJU Int. 2011;107:28–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09648.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacob DA, Bahra M, Langrehr JM, et al. Combination therapy of poly-(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor 3-aminobenzamide and gemcitabine shows strong antitumor activity in pancreatic cancer cells. J of Gastro-enterol and Hepatol. 2007;22:738–748. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kriege M, Brekelmans CT, Boetes C, et al. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Screening Study Group. Efficacy of MRI and mammography for breast-cancer screening in women with a familial or genetic predisposition. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:427–437. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leach MO, Boggis CR, Dixon AK, et al. Screening with magnetic resonance imaging and mammography of a UK population at high familial risk of breast cancer: a prospective multicentre cohort study (MARIBS) Lancet. 2005;365:1769–1778. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66481-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quinn JE, Kennedy RD, Mullan PB, et al. BRCA1 functions as a differential modulator of chemotherapy-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6221–6228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Bono JS, Ashworth A. Translating cancer into targeted therapies. Nature. 2010;467:543–549. doi: 10.1038/nature09339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e1.Robert Koch-Institut (ed.) und die Gesellschaft der epidemiologischen Krebsregister in Deutschland e.V. (eds.) Häufigkeiten und Trends. 7th edition. Berlin: 2010. Krebs in Deutschland 2005/2006. [Google Scholar]

- e2.Schmutzler RK, Rhiem K, Breuer P. Outcome of a structured surveillance programme in women with a familial predisposition for breast cancer. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2006;15:483–489. doi: 10.1097/01.cej.0000220624.70234.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e3.Bosse K, Rhiem K, Wappenschmidt B, et al. Screening for ovarian cancer by trans-vaginal ultrasound and serum CA125 measurement in women with familial pre-disposition; a prospective cohort study. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;1033:1077–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e4.Antoniou A, Pharoah PD, Narod S, et al. Average risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations detected in case series unselected for family history: a combined analysis of 22 studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:1117–1130. doi: 10.1086/375033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e5.Chen S, Iversen ES, Friebel T, et al. Characterization of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in a large US sample. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:863–871. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e6.Albrecht U. Stufe-3-Leitlinie Früherkennung, Diagnostik und Therapie des Mammakarzinoms. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- e7.Ripperger T, Gadzicki D, Meindl A, Schlegelberger B. Breast cancer susceptibility: current knowledge and implications for genetic counselling. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17:722–731. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e8.CHEK2 Breast Cancer Consortium. CHEK2*1100delC and susceptibility to breast cancer: a collaborative analysis involving 10860 breast cancer cases and 9065 controls from 10 studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:1175–1182. doi: 10.1086/421251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e9.Dufault MR, Betz B, Wappenschmidt B, et al. Limited relevance of the CHEK2 gene in hereditary breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2004;110:320–325. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e10.Rahman N, Seal S, Thompson D, Kelly P, et al. PALB2, which encodes a BRCA2-interacting protein, is a breast cancer susceptibility gene. Nat Genet. 2007;39:165–167. doi: 10.1038/ng1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e11.Stacey SN, Manolescu A, Sulem P, et al. Common variants on chromosomes 2q35 and 16q12 confer susceptibility to estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2007;39:865–869. doi: 10.1038/ng2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e12.Hemminki K, Müller-Myhsok B, Lichtner P, et al. Low-risk variants FGFR2, TNRC9 and LSP1 in German familial breast cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:2858–2862. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e13.Turnbull C, Ahmed S, Morrison J, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies five new breast cancer susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2010;42:504–507. doi: 10.1038/ng.586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e14.Antoniou AC, Wang X, Fredericksen ZS, et al. A locus on 19p13 modifies risk of breast cancer in BRCA1 mutation carriers and is associated with hormone-negative breast cancer in the general population. Nat Genet. 2010;42:885–892. doi: 10.1038/ng.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e15.Ramus SJ, Kartsonaki C, Gayther SA, et al. Genetic variation at 9p222. and ovarian cancer risk for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:105–116. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e16.Lakhani SR, Reis-Filho JS, Fulford L, et al. Prediction of BRCA1 status in patients with breast cancer using estrogen receptor and basal phenotype. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:5175–5180. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e17.Dent R, Trudeau M, Pritchard KI, et al. Triple-negative breast cancer: clinical features and patterns of recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4429–4434. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-3045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e18.Robson ME, Chappuis PO, Satagopan J, et al. A combined analysis of outcome following breast cancer: differences in survival based on BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation status and administration of adjuvant treatment. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6:R8–R17. doi: 10.1186/bcr658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e19.Honrado E, Benitez J, Palacios J. The molecular pathology of hereditary breast cancer: Genetic testing and therapeutic implications. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1305–1320. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e20.Bane AL, Beck JC, Bleiweiss I, et al. BRCA2 mutation-associated breast cancers exhibit a distinguishing phenotype based on morphology and molecular profiles from tissue microarrays. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:121–128. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213351.49767.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e21.Metcalfe K, Lynch HT, Ghadirian P. Contralateral breast cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2328–2335. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e22.Tilanus-Linthorst MM, Alves C, Seynaeve C, Menke-Pluymers MB, Eggermont AM, Brekelmans CT. Contralateral recurrence and prognostic factors in familial non-BRCA1/2-associated breast cancer. Br J Surg. 2006;93:961–968. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e23.Rebbeck TR, Friebel T, Lynch HT. Bilateral prophylactic mastectomy reduces breast cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. The PROSE Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1055–1062. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e24.Domchek SM, Friebel TM, Neuhausen SL, et al. Mortality after bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: a prospetive cohort study. Lancet. 2006;7:223–229. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70585-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e25.Risch HA, McLaughlin JR, Cole DE, et al. Poulation BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation frequencies and cancer penetrances: a kincohort study in Ontario, Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1694–1706. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e26.Kirchhoff T, Kauff ND, Mitra N, et al. BRCA mutations and risk of prostate cancer in Ashkenazi Jews. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:2918–2921. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e27.Kadouri L, Ayala H, Rotenberg Y, et al. Cancer risks in carriers of the BRCA1/2 Ashkenazi founder mutations. J Med Genet. 2007;44:467–471. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.048173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e28.Silverman DT, Schiffman M, Everhart J, et al. Diabetes mellitus, other medical conditions and family history of cancer as risk factors for pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 1999;80:1830–1837. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e29.Bartsch DK, Krysewski, Sina-Frey M, et al. Low frequency of CHEK2 mutations in familial pancreatic cancer. Fam Cancer. 2006;5:305–308. doi: 10.1007/s10689-006-7850-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e30.Jones S, Hruban RH, Kamiyama M, et al. Exomic sequencing identifies PALB2 as a pancreatic cancer susceptibility gene. Science. 2009;324 doi: 10.1126/science.1171202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e31.McCabe N, Lord CJ, Tutt AN, Martin NM, Smith GC, Ashworth A. BRCA2-deficient CAPAN-1 cells are extremely sensitive to the inhibition of Poly (ADP-Ribose) polymerase: an issue of potency. Cancer Biol Ther. 2005;4:934–936. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.9.2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e32.Norquist BM, Garcia RL, Allison KH, et al. The molecular pathogenesis of hereditary ovarian carcinoma. Cancer. 2010;116:5261–5271. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e33.Tilanus-Linthorst MM, Kriege M, Boetes C, et al. Hereditary breast cancer growth rates and its impact on screening policy. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:1610–1617. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e34.Warner E, Plewes DB, Hill KA, et al. Surveillance of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers with magnetic resonance imaging, ultrasound, mammography, and clinical breast examination. JAMA. 2004;292:1317–1325. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.11.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e35.Schrading S, Kuhl CK. Mammographic, US, and MR imaging phenotypes of familial breast cancer. Radiology. 2008;246:58–70. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2461062173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e36.Heywang-Köbrunner SH, Schreer I, Heindel W, Katalinic A. Imaging studies for the early detection of breast cancer. Dtsch Ärztebl Int. 2008;105:541–547. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2008.0541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e37.Rhiem K, Flucke U, Schmutzler RK. BRCA1-associated breast carcinomas frequently present with benign sonographic features. Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186 doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.5041. E11-E12; author reply E12-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e38.Lafarge S, Sylvain V, Ferrara M, Bignon YJ. Inhibition of BRCA1 leads to increased chemoresistance to microtubule-interfering agents, an effect that involves the JNK pathway. Oncogene. 2001;20:6597–6606. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e39.Bryant H, Schultz N, Thomas H, et al. Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumors with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature. 2005;434:913–916. doi: 10.1038/nature03443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]