Abstract

Summary: Fragment recruitment, a process of aligning sequencing reads to reference genomes, is a crucial step in metagenomic data analysis. The available sequence alignment programs are either slow or insufficient for recruiting metagenomic reads. We implemented an efficient algorithm, FR-HIT, for fragment recruitment. We applied FR-HIT and several other tools including BLASTN, MegaBLAST, BLAT, LAST, SSAHA2, SOAP2, BWA and BWA-SW to recruit four metagenomic datasets from different type of sequencers. On average, FR-HIT and BLASTN recruited significantly more reads than other programs, while FR-HIT is about two orders of magnitude faster than BLASTN. FR-HIT is slower than the fastest SOAP2, BWA and BWA-SW, but it recruited 1–5 times more reads.

Availability: http://weizhongli-lab.org/frhit.

Contact: liwz@sdsc.edu

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Metagenomic data provide a more comprehensive picture for our understanding of the microbial world. An important step of such understanding is to compare the raw sequencing reads against the available microbial genomes to analyze the phylogenetic composition, genes and functions of the samples. Such a procedure, referred to as fragment recruitment, was introduced in the Global Ocean Sampling (GOS) metagenomics study (Rusch et al., 2007).

Sequences from metagenomic samples exhibit great differences from the available genomes. Although there are thousands of available complete microbial genomes, they hardly cover the broad and diverse species in many metagenomic samples. A typical metagenomic dataset may have hundreds or thousands of species, and many of them are novel. Therefore, it is critical for fragment recruitment methods to align reads to homologous genomes.

In the GOS study, BLAST (Altschul et al., 1997) was used for fragment recruitment. However, it is too slow to handle large datasets. The explosion of next-generation sequencing data stimulated the development of new mapping programs, such as SOAP (Li et al., 2008), Bowtie (Langmead et al., 2009), BWA (Li and Durbin, 2009) and many others. These programs are several orders of magnitude times faster than BLAST, but they can only identify very stringent similarities that tolerate only a few mismatches and gaps. So these mapping programs are insufficient for fragment recruitment. The slightly slower programs like BLAT (Kent, 2002), SSAHA2 (Ning et al., 2001) and LAST (Kielbasa et al., 2011) can recruit more reads than the mapping programs, but their fragment recruiting capacities are still limited. In this article, we present a new fragment recruitment method, FR-HIT. Given reference genomes, metagenomic reads and sequence identity and alignment length cutoffs, the goal of FR-HIT is to align the most reads to references with minimal computational time.

2 METHODS AND IMPLEMENTATION

FR-HIT first constructs a k-mer hash table for the reference genome sequences. Then for each query, it performs seeding, filtering and banded alignment to identify the alignments to reference sequences that meet user-defined cutoffs.

2.1 Constructing k-mer hash table

The reference genome sequences are converted into a k-mer hash table. The default value of k is 11 and can be adjusted from 8 to 12. We include overlapping k-mers at an equidistant step from reference sequences. A reference sequence of length m contains (m − k)/(k − p)+1 k-mers with an overlap of p bases. Here, p is also a user-adjustable parameter. The hash table stores the indexes of reference sequences and the offset positions of k-mers on reference sequences.

2.2 Seeding

Seeding identifies candidate blocks, which are fragments of reference sequences that can be potentially aligned with the query. For each query, we count all its overlapping k-mers and scan the k-mer hash table to collect the k-mers shared by reference sequences.

We identify pieces of reference sequences that the query can be aligned to. These pieces are anchored by the shared k-mers. For a reference, any cluster of ≥ 2 pieces within b bases will derive a candidate block. This block covers all the pieces in that cluster and has extra b bases at each end. Here, b is the bandwidth to be introduced in Section 2.4. If two candidate blocks overlap, they are joined together into one candidate block. We repeat this until no overlapping blocks are observed.

2.3 Filtering

Filtering removes the candidate blocks that do not enclose qualified alignments. K-mer filtering was originally used in QUASAR (Burkhardt et al., 1999). Two sequences of length n with Hamming distance ϵ share at least n + 1 − (ϵ + 1)k common k-mers (Jokinen and Ukkonen, 1991; Owolabi and Mcgregor, 1988). Here, ϵ is the number of mismatches in an alignment. Based on user-defined length and sequence identity cutoffs, we calculate the number of mismatches and reject the candidate blocks that do not have enough common k-mers. In this step, the length of a k-mer is 4.

2.4 Banded alignment

FR-HIT performs banded alignments (Pearson and Lipman, 1988) between the query and the candidate blocks that passed the filter. The bandwidth is also a user-defined value. For each candidate block, the band that contains the most shared k-mers is used. If a reference sequence has multiple candidate blocks, these blocks are sorted by the number of shared k-mers in decreasing order. Banded alignments are performed in this order, and if t banded alignments do not recruit this query, no more banded alignment is tried for this reference. Here, t is a parameter with default value of 10.

2.5 Implementation

FR-HIT is written in C++ and distributed at http://weizhongli-lab.org/frhit with documentation and testing data. FR-HIT takes reference sequences in FASTA format and queries in FASTA or FASTQ format and produce recruitment results. If a query hits multiple references or multiple locations of a reference, FR-HIT reports all these alignments. Currently, FR-HIT does not support reads in color space.

3 RESULTS

We applied FR-HIT on four metagenomic datasets and compared it with BLASTN, MegaBLAST, SOAP2, BWA, BWA-SW, SSAHA2, BLAT and LAST. The first dataset has 1 million 75 bp Illumina reads from MetaHIT sample MH0006 (Qin et al., 2010). The other three datasets are from 454 GS20, GSFLX and Titanium platforms, with 688 590, 288 735 and 502 399 reads, respectively. Their average lengths are 99, 233 and 345 bp, respectively. The GS20 and GSFLX datasets were downloaded from CAMERA (Sun et al., 2011) under IDs SCUMS_SMPL_Arctic and BATS_SMPL_174-2. The Titanium data were from NCBI under accession SRR029691. For the Illumina dataset, we used the 194 human gut genomes from MetaHIT study as reference. For the 454 datasets, we used the 1985 completed bacterial genome sequences downloaded from NCBI in April 2010 as references. The two reference databases are 1.139 and 3.823 GB in size.

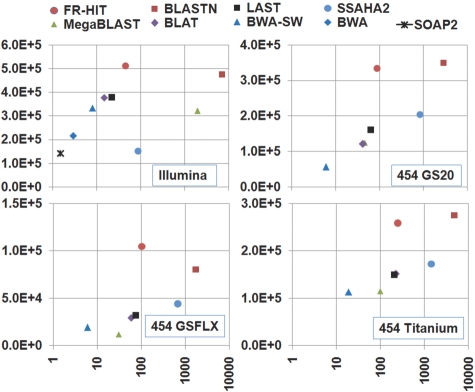

A read is considered recruited if it is aligned to a reference with ≥ 30 bp and ≥ 80% identity. Such cutoffs represent a basic need for fragment recruitment, to recruit more reads and to prevent obviously spurious hits. More discussions and examples of parameters are available in Supplementary Material. Parameters of all the programs are listed in Supplementary Table S2. The CPU time and the number of recruited reads are shown in Figure 1 and Supplementary Table S3. FR-HIT's results with different parameters are provided in Supplementary Table S4. On average, FR-HIT and BLASTN recruited significantly more reads than other programs, FR-HIT is ~ 2 orders of magnitude faster than BLASTN. FR-HIT is slower than the fastest mapping programs SOAP2, BWA and BWA-SW, but it recruited 1–5 times more reads. In these tests, FR-HIT shows better recruitment rate and speed than SSAHA2. FR-HIT is slightly slower than MegaBLAST, BLAT and LAST, but it recruited much more reads than them. Using the Illumina data as an example, BLASTN recruited 475 584 reads in 7168 min. SOAP2 used 1.5 min, but only recruited 141 417 reads.

Fig. 1.

Recruitment rate and speed of FR-HIT and other programs. The x-axis (logarithmic scale) is CPU minute on AMD Opteron 8380 Shanghai 2.5 GHz processors; y-axis is the number of recruited reads. SOAP2 and BWA, short read mapping tools, were only used in Illumina data.

FR-HIT recruited 523 868 reads in 45 min. Metagenomic data contain many novel species, so 49–64% of reads cannot be recruited by FR-HIT. Due to the use of overlapping k-mers, FR-HIT needs more memory than other programs. It used ~ 4 and 8 GB for the two reference databases in these tests.

Funding: Supported by Awards (R01RR025030 and R01HG005978) from National Center for Research Resources and National Human Genome Research Institute.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- Altschul SF, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt S, et al. q-gram based database searching using a suffix array (QUASAR) RECOMB. 1999;99:77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Jokinen P, Ukkonen E. 2 Algorithms for approximate string matching in static texts. Lect. Notes Computer Sci. 1991;520:240–248. [Google Scholar]

- Kent WJ. BLAT–the BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 2002;12:656–664. doi: 10.1101/gr.229202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kielbasa SM, et al. Adaptive seeds tame genomic sequence comparison. Genome Res. 2011;21:487–493. doi: 10.1101/gr.113985.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, et al. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, et al. SOAP: short oligonucleotide alignment program. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:713–714. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning Z, et al. SSAHA: a fast search method for large DNA databases. Genome Res. 2001;11:1725–1729. doi: 10.1101/gr.194201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owolabi O, McGregor DR. Fast approximate string matching. Software Pract. Exper. 1988;18:387–393. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson WR, Lipman DJ. Improved tools for biological sequence comparison. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1988;85:2444–2448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin J, et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature. 2010;464:59–65. doi: 10.1038/nature08821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusch DB, et al. The Sorcerer II Global Ocean sampling expedition: northwest Atlantic through eastern tropical Pacific. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e77. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S, et al. Community cyberinfrastructure for advanced microbial ecology research and analysis: the CAMERA resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D546–D551. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.