Abstract

Fluorescence assays employing semi-synthetic or commercial dansyl-polymyxin B, have been widely employed to assess the affinity of polycations, including polymyxins, for bacterial cells and lipopolysaccharide (LPS). The five primary γ-amines on diaminobutyric-acid residues of polymyxin B are potentially derivatized with dansyl-cholride. Mass spectrometric analysis of the commercial product revealed a complex mixture of di- or tetra- dansyl-substituted polymyxin B. We synthesized a mono-substituted fluorescent derivative, dansyl[Lys]1polymyxinB3. The affinity of polymyxin for purified Gram-negative LPS, and whole bacterial cells was investigated. The affinity of dansyl[Lys]1polymyxinB3 for LPS was comparable to polymyxin B and colistin, and considerably greater (kd < 1 μM) than for whole cells (kd ~6 to 12 μM). Isothermal titration calorimetric studies demonstrated exothermic enthalpically driven binding between both polymyxin B and dansyl[Lys]1polymyxinB3 to LPS, attributed to electrostatic interactions. The hydrophobic dansyl moiety imparted a greater entropic contribution to the dansyl[Lys]1polymyxinB3-LPS reaction. Molecular modeling revealed a loss of electrostatic contact within the dansyl[Lys]1polymyxinB3-LPS complex due to steric hindrance from the dansyl[Lys]1 fluorophore; this corresponded with diminished antibacterial activity (MIC ≥ 16 μg/mL). Dansyl[Lys]1polymyxinB3 may prove useful as a screening tool for drug development.

Keywords: dansyl-polymyxin B, Gram-negative bacteria, binding affinity, polymyxin, colistin, lipopolysaccharide

Introduction

Gram-negative ‘superbugs’, particularly Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Klebsiella pneumoniae, have attracted considerable attention in the last decade due to the escalating incidence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) nosocomial infections [1; 2]. The waning antibacterial drug development pipeline has forced the revival of polymyxin antibiotics as a last line of defense against these infections [3]. Both polymyxin B and E (also known as colistin) are used clinically, although recent experience has been more frequently documented with colistin. Worryingly, the emergence of pan-drug resistant strains which are even resistant to colistin [4; 5; 6] has prompted fears that life-threatening MDR infections will soon become untreatable. Investigations into the mechanisms of polymyxin action and resistance are warranted in order to provide a platform for the redevelopment of polymyxins, ensuring efficacy is retained and resistance is minimized.

The complex cell envelope of these Gram-negative pathogens comprises an inner (cytoplasmic) and outer membrane separated by periplasm [7]. The inner membrane is composed of a bi-layer of phospholipids, while the asymmetrical outer membrane embraces a phospholipid inner leaflet and an outer leaflet, predominantly containing lipopolysaccharide (LPS) [8]. LPS exhibits a unique amphipathic structure consisting of three domains; an outer O-antigen connected to a core oligosaccharide, which is adjacent to lipid A [9]. Poly-anionic character is conveyed by phosphate and carboxyl functionalities on lipid A and sugars of the core domain. Thus, the formation of a charged bacterial surface layer is advantageous for the action of polymyxins, which are cationic peptides.

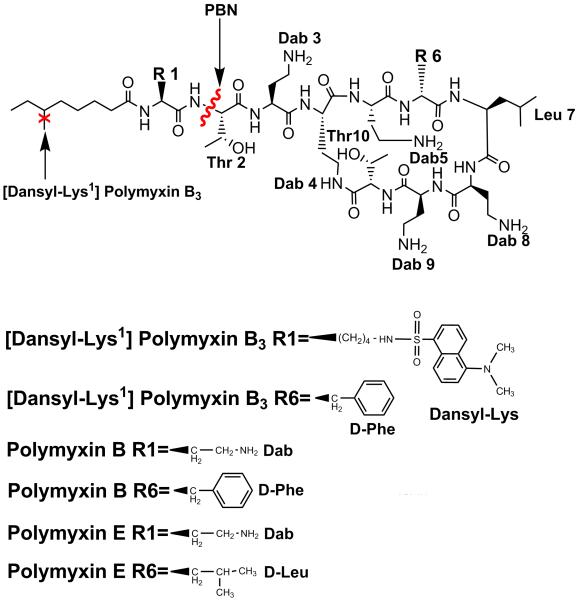

Polymyxins are structurally characterized by a cyclic heptapeptide ring, together with a tripeptide side chain that is covalently attached to a fatty acyl chain (Figure 1) [10]. The putative mechanism of polymyxin action involves two-steps; firstly, electrostatic interaction of the positively-charged Dab residues with negatively-charged lipid A phophorester groups [11; 12] displaces divalent cations (Mg++ and Ca++) that play a role to cross-link adjacent LPS molecules. Subsequent insertion of the polymyxin fatty acyl tail and D-Phe6-L-Leu7 motif through the destabilized membrane encourages the formation of hydrophobic contacts with the bacterial fatty acyl leaflet. The assembly of amphipathic polymyxin molecules into a macromolecular complex [13; 14] directs a dramatic reorientation of the aggregate structure, which interrupts the tightly-packed LPS leaflet. In this manner, ‘self-promoted uptake’ is enabled across the membrane [15].

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of polymyxin B1, polymyxin E1 (colistin A), polymyxin B nonapeptide (PBN) and [dansyl-lys]1polymyxin B3 (DPmB3).

For a thorough understanding of the crucial binding interaction mediating polymyxin uptake, quantitative biophysical assays of polymyxin affinity for isolated LPS or whole cells is of considerable value. For this purpose, a fluorometric assay has been employed utilizing dansyl-polymyxin B (DPmB) [16; 17]. Semi-synthetic coupling of Dab amino groups on polymyxin B to a dansyl fluorophore [18] results in the formation of DPmB; the low intrinsic fluorescence yield of the dansyl moiety in polar surroundings is considerably enhanced amidst apolar environments, such as when bound to LPS or a cell membrane [19]. Subsequent reduction in fluorescence upon addition of a competing cationic ligand (such as a polymyxin) displaces bound DPmB, which may be interpreted to describe the binding affinity of the competing ligand [17].

The apparent simplicity of this assay has been augmented by the commercial availability of DPmB and the ease of semi-synthesis [18]. Binding of numerous antimicrobials to isolated LPS [16; 17; 20; 21; 22] and Gram-negative bacteria [23; 24; 25; 26] has been described, although no attempt has been made to characterize the nature or extent of dansyl substitution on DPmB. An inaccurate representation of the binding mechanism of the parent compound may potentially arise from structural inadequacies associated with the DPmB probe. Our aim here was to design and synthesize a fully synthetic [Dansyl-Lys]1Polymyxin B3 (DPmB3) probe, as a minimally dansylated PmB structure. Subsequent evaluation of the binding interaction between DPmB3 and isolated LPS or whole bacterial cells has enabled contrasts to be drawn between colistin and DPmB3 with respect to both mechanistic and structural aspects of these interactions. Thus deficiencies of semi-synthetic or commercial preparations of DPmB for this popular assay have been highlighted.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Polymyxin B sulfate (lot # 453306, ≥6000 USP units per mg) was purchased from Fluka (Castle Hill, NSW, Australia). Colistin sulfate (lot # 036K1374, 15,000 units per mg), dansyl chloride, 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES; 99.5%), chloramphenicol (98%), sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS; 99%), DNase and RNase were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Sydney, NSW, Australia). Proteinase K was obtained from Promega (Sydney, NSW, Australia). Semi-synthetic dansyl-polymyxin B (DPmB) was from Invitrogen Molecular Probes (Melbourne, VIC, Australia) or prepared as described below. K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, Salmonella enterica and Escherichia coli LPS were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich or purified as described below. Polymyxin B nona-peptide (PBN) was prepared as previously described and purified by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) [27].

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Whole cell experiments were conducted on E. coli (BL21) and two colistin hetero-resistant A. baumannii strains, clinical isolate FADDI-AB016 and reference strain ATCC 19606 (from the American Type Culture Collection, VA, USA). Paired colistin-resistant strains were selected from wildtype A. baumannii strains by growth in the presence of 10 μg/mL colistin; these were termed ‘R’ strains.

All bacterial strains were stored at −80°C and subcultured onto nutrient agar plates before the experiments (Medium Preparation Unit, University of Melbourne, Australia). Overnight cultures were prepared using cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (CaMHB; Oxoid, Thebarton, SA, Australia), following which fresh broth was inoculated and grown to the desired growth phase according to OD600nm. Identical procedures were adopted for colistin-ressitant (R) strains except that the initial subculture and overnight culture was conducted in the presence of 10 μg/mL colistin. All broth cultures were incubated at 37°C in a shaking water bath (100 rpm).

Isolation of LPS

LPS was extracted by a modified phenol/water procedure [28]. Briefly, mid-logarithmic phase cells in CaMHB (500 mL) were pelleted by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 10 min at 4°C, then washed and resuspended in 40 mL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2). Cell lysis was achieved by sonication on ice (5 × 30 sec) following which unbroken cells and debris were removed by centrifugation at 5,400 g for 45 min at 4°C. Further centrifuging of the supernatant was conducted for 1 h at 16,000 g. Addition of DNase and RNase to the re-suspended pellet (in 2 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0) at final concentrations of 80 U/mL and 50 U/mL, respectively, served to digest nucleic acids. The solution was incubated for 2 h at 37°C before addition of 50 μg/mL. Proteinase K. Following 2 h incubation at 56°C, samples were mixed with an equal volume of pre-heated phenol at 65°C and incubated at the same temperature for 15 min, then cooled to room temperature and centrifuged at 5,400 g for 45 min. The phenol phase was re-extracted twice, allowing the aqueous phase to be collected and dialyzed with a Slide-A-lyzer→ dialysis Kit (Pierce, IL, USA). Purified LPS samples were freeze dried and stored at −80°C. LPS was characterized by SDS-PAGE on 15% acrylamide resolving and 5% acrylamide stacking gels using the Tris-HCl buffer system of Laemmli [29]. Silver staining was utilized to visualize LPS bands [30].

Susceptibility tests

The MICs for each peptide were determined with the broth microdilution method [31] against A. baumannii ATCC 19606 (colistin MIC 1 μg/mL), A. baumannii ATCC 19606R (colistin MIC >128 μg/mL), a colistin-resistant A. baumannii clinical isolate (colistin MIC 16 μg/mL), a colistin-resistant P. aeruginosa clinical isolate (colistin MIC >128 μg/mL), K. pneumoniae ATCC 13883 (colistin MIC 1 μg/mL) and a colistin-resistant K. pneumoniae clinical isolate (colistin MIC >128 μg/mL). P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 (colistin MIC 1 μg/mL) was employed as a quality control. Peptide concentrations ranged from 0.125 to 32 μg/mL. Cell viability was determined for the wells at the MIC. Viable bacteria were counted following incubation at 35°C for 20 h. Each experiment was done in two replicates. The limit of counting was 10 CFU/mL.

Synthesis of DPmB3

[Dansyl-Lys]1PmB3 was synthesized by AltaBiosciences (Birmingham, UK) by conventional solid-phase Fmoc-based peptide synthesis according to a previously reported method [32] (Supplementary Figure 1). The side chain amino group of the diaminobutyrate residue involved in cyclization of the peptide was protected by t-butoxycarbonyl (tBoc), the remaining side chains were protected as benzyloxycarbonyl (Z) derivatives. The partially protected peptide was cleaved from the resin by reaction with a solution of 95% trifluoroacetic acid and 5% water for 2 h at room temperature. The resulting peptide was precipitated with diethyl ether. Cyclization was performed in solution using benzotriazole-1-5 oxy-tris-pyrrolidinophosphonium hexafluorophosphate (PyBop), N-hydroxybenzotriazole (HoBt), and N-methyl morpholine (NMM) at the molar excess of 2, 2, and 4, respectively. The cyclization mixture was added to the peptide (dissolved in dimethylformamide (DMF)) and allowed to react for 2 h, and precipitated by the addition of cold diethyl ether. Residual PyBop was removed by washing the peptide with water. The remaining benzyloxycarbonyl side chain protection groups (Z) were removed by catalytic hydrogenation (i.e., by subjecting the peptide dissolved in acetic acid:methanol:water [5:4:1] to an atmosphere of hydrogen in the presence of a palladium charcoal catalyst). The peptide was purified by reversed-phase HPLC using conventional gradients of acetonitrile:water:trifluoroacetic acid. The product was dried by lyophilization. The purity, as estimated by reversed-phase HPLC, was more than 95% (Supplementary Figure 2).

Semi-synthesis of DPmB

DPmB was synthesized as previously described with minor modifications to the original protocol [33]. Briefly, a mixture of 40 mg PmB (in 1.2 mL of 0.1 M NaHCO3) and 10 mg dansyl chloride (in 0.8 mL of acetone) was incubated in the dark for 90 min at 20°C, then loaded onto a Sephadex G-25 PD-10 column (GE Health Care, Melbourne Australia). Fractions (1 mL) were subsequently collected following equilibration with 10 mM Na-phosphate buffer, 0.15 M NaCl (pH 7.1). DPmB eluted as a fairly broad peak ahead of the unreacted dansyl chloride peak. The yellow fluorescence of the DPmB fractions was detected using a UV lamp, and differentiated from unreacted dansyl chloride which emits a blue-green fluorescence. DPmB-containing fractions were extracted into a 1/2 volume of n-butanol, which was then evaporated in a desiccator over 24 h. Dried DPmB was dissolved in 5 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.2) and stored at −80°C before use.

Mass spectrometry analysis of commercial and semi-synthetic DPmB

LC/MS analysis was conducted on a Waters Micromass Quattro Ultima Pt triple quadrupole instrument coupled to a Waters Acquity UPLC. Chromatographic separation was performed on a Supelco Ascentis Express C18 column (2.7 μm particle size, 50×2.1 mm with gradient elution with 0-100% acetonitrile buffered with 0.05% formic acid as the mobile phase sustained at 0.4 mL/min. MS spectra were acquired in positive electrospray ionization mode with a capillary voltage of 3.2 kV and a cone voltage of 50 eV from 100 to 1,000 Daltons with 1 second scan time. Collision-induced dissociation (CID) experiments were conducted on a Waters Micromass Quattro Premier triple quadrupole instrument by direct infusion. The DPmB mixture was diluted two-fold in 1:1 acetonitrile / 0.1 M ammonium formate (to maximize detection of double-charged species) and introduced into the mass spectrometer directly via a syringe pump at 10 μL/min. CID experiments were conducted in positive electrospray ionization mode with a capillary voltage of 3.2 kV, and a cone voltage and collision energy of 50 and 30 eV, respectively. CID spectra were acquired from 100 to 2,000 Daltons with 1 second scan time over 2 min.

Fluorometric assay of binding of dansylated PmB to whole cells and isolated LPS

Purified LPS suspensions (3 mg/L) were prepared in 5 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.0). Whole bacterial cells were washed twice and re-suspended in 5 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.0) containing 5 mM sodium azide, to a final OD600nm of 0.5. LPS or whole cells were added into a quartz cuvette containing 1 mL of the same buffer, following which aliquots of DPmB3 solution were titrated at 2 min intervals until fluorescence intensity reached a plateau. Fluorescence was measured using a Cary Eclipse Fluoresence spectrophotometer (Varian, Mulgrave, Victoria, Australia) set at an excitation wavelength of 340 nm. Slit widths were set to 5 and 10 nm for the excitation and emission monochromators, respectively. Emission spectrum was collected from a wavelength of 400 – 650 nm; the emission maximum for bound DPmB3 was observed at approximately 485 nm for LPS and 500 nm for whole cells.

Fluorescence enhancement was determined from the integrated area under the emission spectrum. The dissociation constant (Kd) of the DPmB3 complex with LPS or whole cells was determined by non-linear regression analysis of the binding isotherms. The background-corrected DPmB3 binding fluorescence data were fitted to a one-site binding model (Eq1).

| (Eq 1) |

ΔF represents the specific fluorescence enhancement upon the addition of DPmB3 to a fixed concentration of LPS or whole cells, ΔFmax is the maximum specific fluorescence enhancement at saturation, Kd represents the dissociation constant for DPmB3 binding to LPS or whole cells obtained from the concentration of DPmB3 equivalent to half ΔFmax determined from the data fit, and [L] represents the total concentration of DPmB3 (it is assumed that ligand depletion is not in effect and only a small fraction of the total DPmB3 is bound). For LPS investigations, identical experiments were performed using commercial and semi-synthetic DPmB preparations.

Displacement of DPmB3 from isolated LPS (dansylated PmB)

DPmB3 was added to a quartz cuvette containing LPS at a concentration necessary to obtain 90 to 100% of the maximum fluorescence when bound. Displacement of DPmB3 was measured as the corresponding decrease in fluorescence upon the progressive titration of aliquots of PmB or colistin solutions at 2-min intervals, until no further decrease in fluorescence was observed.

Fluorescence readings were corrected for dilution before plotting the fraction of DPmB3 bound as a function of the concentration of the displacing polymyxin (i.e. PmB or colistin). The concentration of polymyxin required to displace 50% of the bound DPmB3 (I50) was determined by fitting the fluorescence data to a sigmoidal dose-response model which assumed a single class of binding sites (Eq 2):

| (Eq 2) |

I50 is the midpoint of competition and is defined as the concentration of displacer at which the maximum fluorescence intensity (Fmax) of the DPmB3-saturated complex is reduced to 50% of the initial value. Fmin represents the maximum DPmB3 displacement produced by the competitor and is defined by the bottom plateau of the displacement curve; [L] represents the concentration of the competitor. The inhibition constant (Ki) is determined from the following equation (Eq 3):

| (Eq 3) |

Kd DPmB3 represents the dissociation constant for the DPmB3-LPS complex. All data modeling operations were performed with GraphPad Prism V5.0 software (GraphPad software, San Diego, CA, U.S.A).

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) assay of binding of PmB and DPmB3 to isolated LPS

Microcalorimetric measurements of PmB and DPmB3 binding to LPS were performed on a VP-ITC isothermal titration calorimeter (Microcal, Northampton, MA). All samples were thoroughly degassed beforehand. In the ITC experiments, isolated E. coli LPS (0.125 mM) dissolved in 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.0) were filled into the microcalorimetric cell (volume, 1.3 mL) and titrated with 80 × 3 μL injections of a 3 mM PmB or DPmB3 solution at 240-sec intervals from a 250-μL injection syringe. The cell contents were stirred constantly at 307 rpm. ITC titrations were performed at 37°C. The system was allowed to equilibrate and a stable baseline was recorded before initiating an automated titration. The heat of interaction after each injection measured by the ITC instrument was plotted versus time. As a control for and all ITC experiments, PmB and DPmB3 were titrated into buffer under the same injection conditions the heat of dilution was subtracted from the LPS titration data. The total heat signal from each injection was determined as the area under the individual peaks and plotted versus the [polymyxin]/[LPS] molar ratio. All titration measurements were conducted three times.

The corrected data were analyzed to determine number of binding sites (n), and molar change in enthalpy of binding (ΔH) by nonlinear least square regression analysis in terms of an equation series that define two sets of independent sites [34].

The binding constants (K) for each site are defined by Eq 4 & 5; Θ represents the fraction of sites occupied by the PmB or DPmB3; where [X] is the free concentration of PmB or DPmB3.

| (Eq 4) |

The total concentration of PmB or DPmB3 Xt is defined by:

| (Eq 5) |

where Mt is the total concentration of LPS in Vo the active cell volume.

Solving Eq 4 for Θ1 and Θ2 and substituting into Eq 5 leads to the cubic equation of the form:

| (Eq 6) |

where

Eq 6 was solved for [X], then Θ1 and Θ2 were obtained from Eq 4.

Q the total heat content of the solution in Vo at fractional saturation is given by:

| (Eq 7) |

Following correction for the displaced volume, the calculated heat effect from the ith injection is given by Eq 8 to obtain the best fit for n1, n1, K1, K2 and ΔH1, ΔH2 by standard Marquardt methods until no further significant improvement in fit occurs with continued iteration [34; 35].

| (Eq 8) |

All data fitting operations were performed with Origin V8.0 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA).

ΔG0 and ΔS0 were calculated from the fundamental equations of thermodynamics Eq 9 and 10, respectively:

| (Eq 9) |

| (Eq 10) |

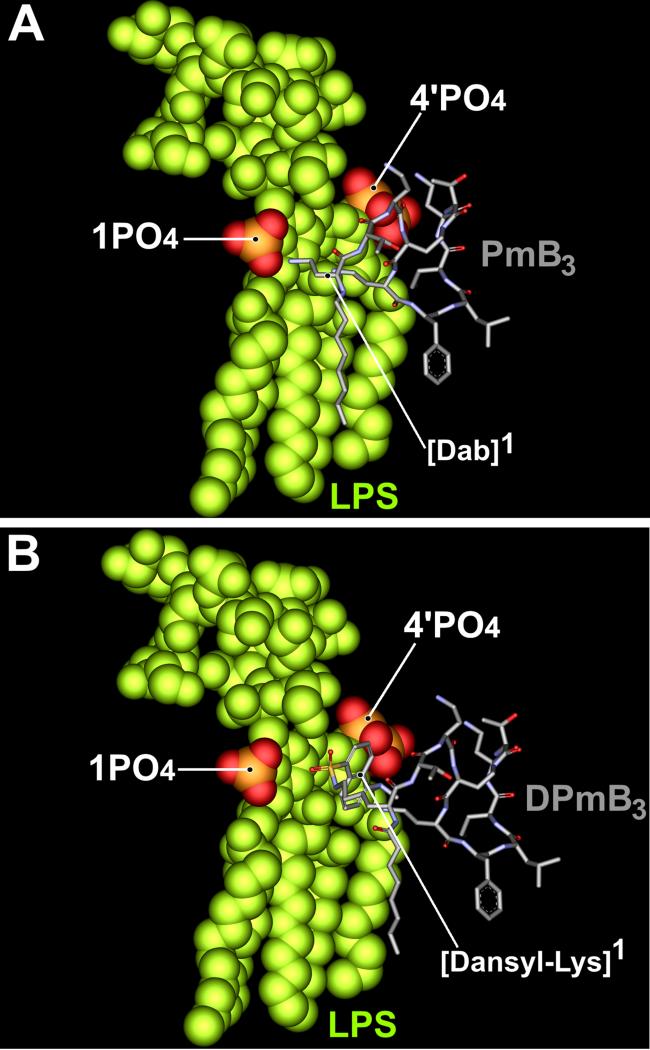

Molecular modeling of the DPmB3-LPS complex

The model of DPmB3 in complex with LPS was constructed using Accelrys Discovery Studio V2.1 (Accelrys, San Diego, CA). The coordinates of the NMR solution structure of PmB when bound to E. coli LPS were obtained from Pristovsek and Kidric [36] and the dansyl-Lys substitution at position 1 was modeled onto the structure. The coordinates of E. coli LPS were derived from the crystal structure of FhuA, the receptor for ferrichrome-iron in E. coli with bound LPS (PDB code:1QFF) [37; 38]. DPmB3 was manually docked onto the LPS molecule and the complex was energy minimized in vacuum. The modeling process took into account the electrostatic interactions between the positively charged Dab amine groups of DPmB3 and the negatively charged phosphoester groups on the lipid A, and in addition maximized the reduction of solvent-exposed hydrophobic area on all molecules. Molecular representations were rendered using the POVRAY software package Persistence of Vision Raytracer (Version 3.6; http://www.povray.org). Chemical properties of DPmB3 were calculated using Chem3D (Version 10.0; Cambridge Soft) and Advance Chemistry Development software (Version 6.0; ACD Laboratories, Toronto, Canada).

Results

Mass spectrometry (MS) analysis of semi-synthetic and commercial DPmB

MS analysis of non-purified products from the semi-synthetic reaction showed the PmB remained unreacted or in mono-, di-, tri- or tetra-dansyl-PmB form (Supplementary Figures 3.1-3.6). Similarly, commercial DPmB was found to be a complex mixture of mono-, di-, tri- and tetra-dansyl-PmB although underivatised polymyxin was not detected.

In positive mode electrospray ionization MS analysis of the commercial DPmB, multiple charged molecular ions between 2 to 4 positive charges were observed depending on the pH of the solution. Under acidic conditions, triple and quadruple charged species were more prominent in the 0.5% formic acid-acetonitrile (1:1 v/v) medium, whereas double charged ions were predominant in the less acidic 0.1 M ammonium formate-acetonitrile (1:1 v/v) medium. Using precursor scans from the acyl-Dab1 fragment ions of polymyxin B1 and B2 at m/z 223 and 209, respectively, a mixture of ions due to polymyxin B1 and B2 with 1 to 4 dansylation were observed (Supplementary Figure 3.3).

LC/MS separation of dansylation mixture was conducted in acetonitrile – water gradient buffered with 0.05% formic acid to reduce the polarity and hence the elution time of the poly-dansylated products. Thus, mass chromatograms shown in Supplementary Figures 3.1 and 3.2 corresponded to the triple charged molecular ions of dansylation products of polymyxin B1 and B2, respectively. Also, there is likely to be more than one dansylated compound under each peak.

For structure confirmation, the 0.1 M ammonium formate-acetonitrile medium was used to select double charged ions for the generation of simpler CID spectra. Supplementary Figures 3.4 and 3.5 show the CID spectra supporting the assignment of the positions of the dansyl group for the mono- and di-dansylation of polymyxin B1 and B2. Supplementary Figure 3.6 illustrates the fragmentation pathway for the side chain part only to illustrate the dansylation of Dab1. Spectral assignment reveals the site(s) of dansylation appeared to be non-specific. For example, the presence of both underivatized and dansylated Dab1 was found for each dansylated product in CID spectra. Fragmentation of the double charged molecular ions gave a series of double charged fragment ions: the loss of water molecules (−9), loss of Dab (−50) and the loss of acyl-Dab1 (−120 for B1 and −113 for B2). Observation of the loss of acyl-Dab1 suggested that Dab1 was not derivatised. For example, Supplementary Figure 3.4A shows mono-dansyl polymyxin B1, [M+2H]2+ at m/z 719, gave fragment ions at m/z 710 (loss of 1 water), 701 (loss of 2 water), 669 (loss of 1 Dab) and 599 (loss of acyl-Dab1). Supplementary Figure 3.4B shows mono-dansyl polymyxin B2, [M+2H]2+ at m/z 712, gave fragment ions at m/z 703 (loss of 1 water), 694 (loss of 2 water), 662 (loss of 1 Dab) and 599 (loss of acyl-Dab1). Supplementary Figure 3.5A shows di-dansyl polymyxin B1, [M+2H]2+ at m/z 836, gave fragment ions at m/z 827 (loss of 1 water), 818 (loss of 2 water), 786 (loss of 1 Dab) and 716 (loss of acyl-Dab1). Supplementary Figure 3.5B shows di-dansyl polymyxin B2, [M+2H]2+ at m/z 829, gave fragment ions at m/z 820 (loss of 1 water), 811 (loss of 2 water), 779 (loss of 1 Dab) and 716 (loss of acyl-Dab1).

Single charged fragment ions were observed also from the double charged molecular ions. The single charged ion at m/z 996 corresponds to the loss of the exocyclic peptide chain (acyl-Dab-Thr-Dab). It was observed for both the mono- and di-dansylated polymyxin B1 and B2, suggesting that the dansyl group(s) were located on the side chain. Single charged fragment ions corresponding to the cleavage of the cyclic peptide were observed at m/z 101 (Dab), 202 (Dab-Thr), 302 (Dab-Dab-Thr). The presence of dansylation at Dab1 was supported by the series of single charged fragment ions corresponding to the sequential loss of a dansyl group (−233) and water (−18) from the acyl-Dab1(dansyl) fragment ion. For dansylated polymyxin B1 this corresponded to m/z 474, 241, 223 and for dansylated polymyxin B2: m/z 460, 227, 209.

Susceptibility testing

Antibacterial activity was not displayed by commercial preparations of DPmB (MIC > 32 μg/mL). The MICs of DPmB3 against colistin-susceptible P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 and the colistin-resistant P. aeruginosa clinical isolate were 16 μg/mL and 32 μg/mL, respectively. Viable cells were not detected in the MIC wells of these two isolates treated with DPmB3; the limit of detection was 20 cfu/mL for P. aeruginosa ATCC 27583, and 650 cfu/mL for the colistin-resistant P. aeruginosa clinical isolate. Activity was not observed for DPmB3 against all other tested strains (MICs > 32 μg/mL).

Fluorometric assay of binding interactions of dansylated PmB, PmB and colistin with isolated LPS and whole cells

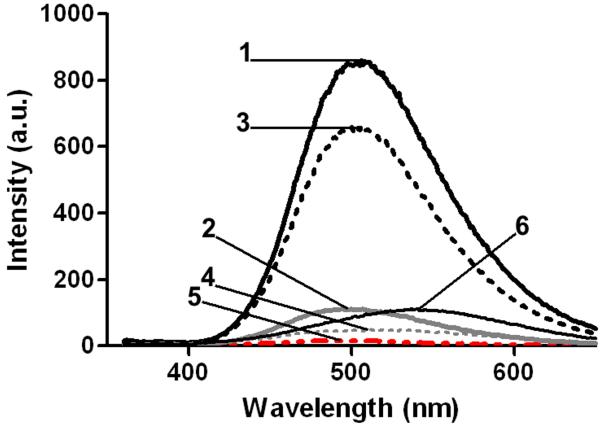

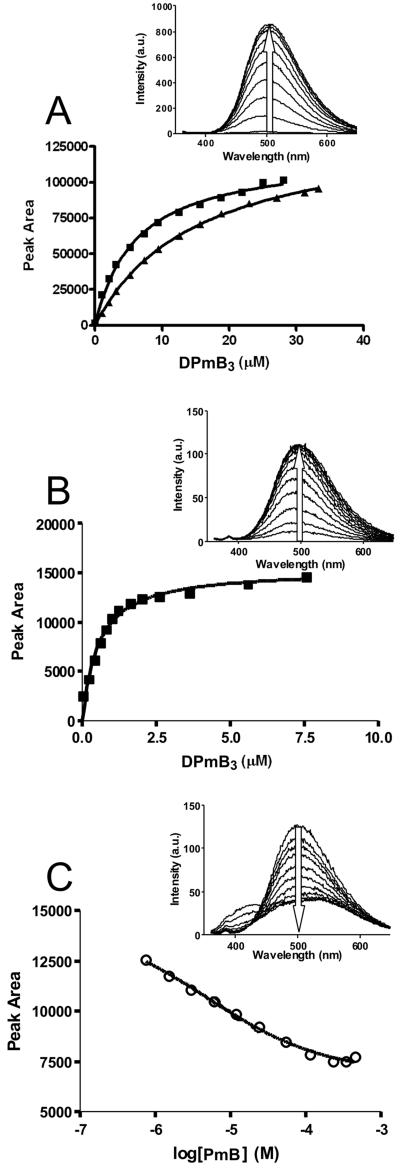

Free DPmB fluoresces at an emission wavelength maximum of ~550 nm (Figure 2). Fluorescence intensity was noted to increase and exhibit a characteristic blue shift in the emission spectrum to ~485 nm and ~500 nm, upon binding to LPS and whole cells, respectively (Figure 2). The rise in fluorescence at these wavelengths was monitored with each successive addition of DPmB3 until no further increase was detected, indicating all binding sites were occupied. Additional titration of DPmB3 beyond this point resulted in a red-shift (Figure 2), highlighting the increasing presence of free DPmB3 in aqueous buffer. Saturable binding was demonstrated for all experiments conducted with both whole cells (Figure 3A) and isolated LPS (Figure 3B), from which the Kd values were calculated (Table 1). The fully synthetic DPmB3 displayed a comparable binding affinity to that of PmB and colistin for isolated LPS from E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and S. enterica (Table 1). The concentration of polymyxins or analogs required to achieve 50% displacement (I50) was used to calculate Ki values as a measure of affinity of the displacing compound. The ability of colistin, PmB and polymyxin B nonapeptide (PBN) to compete with DPmB3 for binding to LPS and whole cells, was then examined by incremental titration with a competing polymyxin peptide until no reduction in fluorescence intensity was detected upon further addition. In line with the similar chemical structure of their lipid A components, there were no species specific differences in the binding affinity of DPmB3, PmB or colistin for isolated LPS from E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and S. enterica. However, in the case of P. aeruginosa LPS, DPmB3 displayed a higher affinity than PmB and colistin. Experiments conducted using the commercial and in-house semi-synthetic preparations of DPmB with LPS samples, revealed a lower binding affinity for each LPS isolate compared to DPmB3, PmB and colistin (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Fluoresence emission spectra illustrating the enhanced fluorescence emission upon binding of DPmB3 (12 μM) to (1) A. baumannii cell suspension (final OD600nm of 0.5) and (2) E. coli LPS (3 mg/L); (3) reduction in fluorescence observed upon addition of colistin to whole A. baumannii cell suspension (final OD600nm of 0.5) and (4) LPS (3 mg/L). (5) The emission spectra of unbound A. baumannii cell suspension (final OD600nm of 0.5) and LPS (3 mg/L) in 5 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.0). (6) The emission spectra of free DPmB3 (12 μM) in buffer.

Figure 3.

(A) Fluorescence assay of the direct binding of DPmB3 to A. baumannii ATCC 19606 (■) and ATCC 19606R (▲) whole cells. Inset. The increase in fluorescence emission upon titration of whole cells with DPmB3. (B) Fluorescence assay of the direct binding of DPmB3 to E. coli LPS (■). Inset. The increase in fluorescence emission upon titration of E. coli LPS with DPmB3. (C) Displacement of DPmB3 from E. coli LPS by titration with PmB (○). Inset. The decrease in fluorescence upon displacement of DPmB3 by titration with PmB. Solid lines represent non-linear least squares regression fits as detailed under materials and methods.

Table1.

Fluorometric assay data for the binding affinity of polymyxins to isolated LPS

| Lipid A | Kd*; Ki# Binding Affinity (μM) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPmB3* [Dansyl- Lys]1polymyxinB3 |

DPmB* Invitrogen preparation |

DPmB* in-house preparation |

PmB# | Colistin# | PBN# | |

| E. coli [9; 57] | 0.5±0.1 | 3.2±0.5 | 4.6±0.7 | 0.5±0.1 | 0.8±0.1 | 30±4.8 |

| K. pneumoniae ATCC 13883 [58] | 0.6±0.1 | 2.9±0.6 | 5.3±0.9 | 0.5±0.2 | 0.6±0.1 | 26±10 |

| S. enteric [57; 59] | 0.6±0.1 | 4.5±0.8 | 7.0±1.5 | 0.4±0.1 | 0.6±0.1 | 36±8.1 |

| P. aeruginosa [42] | 1.2±0.2 | 6.8±2.0 | 8.7±1.8 | 3.5±0.2 | 3.8±0.1 | 48±7.8 |

Kd Binding affinity constant determined from direct titration with DPmB or DPmB3

Ki Binding inhibition constant determined by displacement of DPmB3

All values are the mean of three independent measurements ± SD

Binding affinity values for E. coli and A. baumannii whole cells differed markedly from the isolated LPS binding affinity values. DPmB3 bound to colistin-susceptible A. baumannii cells with considerably greater affinity (ATCC 19606 Reference strain Kd= 7.9 ± 2.6μM; FADDI-AB016 Clinical isolate Kd=6.6 ± 2.3μM) than colistin-resistant cells (ATCC 19606R Colistin-resistant derivative Kd=17 ± 3.4; FADDI-AB016R Colistin-resistant derivative Kd=11 ± 1.3). Analysis of data obtained from competitive displacement experiments conducted on whole cells did not yield reliable I50 values, as a fraction of DPmB3 fluorescence was observed to persist regardless of the concentration of competing PmB or colistin added.

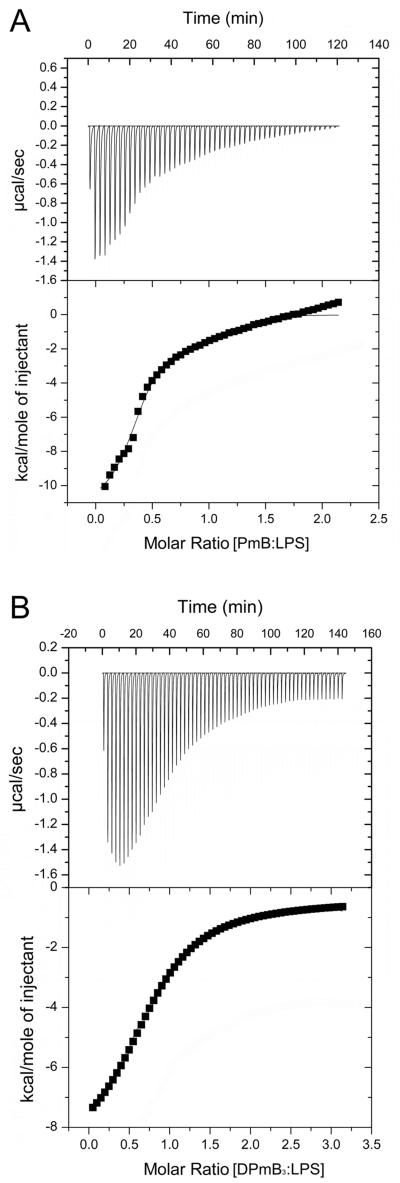

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) assay of PmB and DPmB3 binding to isolated LPS

In order to examine DPmB3-LPS binding directly we have characterized the interaction thermodynamically using ITC. Typical microcalorimetric titrations of E. coli LPS (0.125 mM) with 3 mM PmB and DPmB3 are shown in Figure 4. Titration curves corresponding to an exothermic reaction were observed for both PmB (Figure 4A) and DPmB3 (Figure 4B). Plots of the enthalpy changes measured calorimetrically versus the polymyxin peptide:LPS ratio for both PmB and DPmB3 could not be faithfully fitted to a one-site interaction model; however, both data sets conformed well to a model which defines two independent sites (cf. Methods) indicating the existence of two binding sites on the LPS aggregates. The calculated microscopic thermodynamic parameters from the ITC binding curves measured at 37°C are documented in Table 2.

Figure 4.

Isothermal titration calorimetric data for the binding of (A) PmB and (B) DPmB3 to E. coli LPS at 37°C in 20 mM HEPES pH 7.0 buffer. The 1.3 mL of LPS in the calorimetric cell was titrated every 240 sec with 3 μL of 3 mM polymyxin peptide. Top panels. The raw data are shown as a plot of the heats (μcal, microcalories) associated with binding of the polymyxin to E. coli LPS as a function of injection time. Bottom panels. Enthalpy change of the polymyxin peptide-LPS reaction as a function of the [polymyxin peptide]:[LPS] molar ratio from calorimetric titration data in the respective top panels. The solid line through the data represents the non-linear least squares fit of the data to a two-site binding model.

Table 2.

Isothermal titration calorimetric parameters for binding of PmB and DPmB3 to E. coli LPS at 37°C

| Parameter | PmB | DPmB3 |

|---|---|---|

| n1 | 0.95 ± 0.05 | 2.0 ± 0.3 |

| Kd1 (μM) | 1.5 ± 0.7 | 192 ± 15 |

| ΔH1 (kcal/mol) | −1.5 ± 0.4 | −438 ± 25 |

| −ΔGo1 (kcal/mol) | −8.4 | −1.1 |

| ΔS1 (kcal/mol) | 6.9 | −437 |

| n2 | 0.84 ± 0.30 | 0.48 ± 0.10 |

| Kd2 (μM) | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 24 ± 7.2 |

| ΔH2 (kcal/mol) | −12 ± 3.7 | −10 ± 2.7 |

| −ΔGo2 (kcal/mol) | −10.2 | −6.7 |

| ΔS2 (kcal/mol) | −1.8 | −3.3 |

The microscopic thermodynamic parameters for the first set of sites of the PmB-LPS interaction revealed an approximately 1:1 binding stoichiometry with a high binding affinity in the low micromolar range (1.5 μM), which correlates well with the binding affinity determined fluorometrically. This reaction displayed favorable enthalpic and entropic components. The parameters for the second set of sites for the PmB-LPS reaction indicated a sub-stoichiometric binding ratio with a very high binding affinity (0.08 μM). This second phase of the reaction was largely driven by a favorable enthalpic component and displayed an unfavorable, negative entropic component.

The microscopic thermodynamic parameters for the first set of sites of the DPmB3-LPS interaction revealed a 2:1 (DPmB3:LPS) stoichiometry with a very low binding affinity (192 μM) (Table 2). The reaction was driven by a large enthalpic contribution which was accompanied by a large unfavorable entropy. The second phase of the reaction was characterized by a sub-stoichiometric binding ratio with an intermediate binding affinity (24 μM). This phase of the reaction was also enthalpically driven and associated with a small, unfavorable entropy.

The ΔH versus the PmB or DPmB3:LPS ratio plots show that saturation of binding took place initially at a molar ratio of 5:1 [PmB]:[LPS] and 10:1 [DPmB3]:[LPS] (Figure 4). Saturation of the reaction began by the 14th injection for PmB where the absolute concentration of PmB in the cell was 98 μM; whereas saturation of the DPmB3 titration began by the 18th injection where the absolute concentration of DPmB3 in the cell was 126 μM. The absolute concentration of LPS in the cell was 125 μM in both titration experiments. Given the fact that PmB and DPmB3 bear five and four positive charges, respectively, and LPS four negative charges, charge compensation would be expected to take place at a molar ratio of [PmB]:[LPS] = 0.8 and [DPmB3]:[LPS] = 1.0. The observed values correspond well to charge compensation in both cases.

Molecular modeling of the DPmB3-LPS complex

In an attempt to understand how the position 1 dansyl-Lys substitution abolishes the antibacterial action of PmB on the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, we have constructed a molecular model of the DPmB3-LPS complex and compared this to the experimental PmB-LPS complex which is based on NMR constraints [36] (Figure 5). The PmB-LPS complex is stabilized by a combination of electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions. The fatty acyl chain and D-Phe6-L-Leu7 side chains of PmB penetrate into the hydrocarbon portion of lipid A, packing against the fatty acyl chains (Figure 5A [38]). The positively charged Dab amine groups form electrostatic contacts with the negatively charged 4′- and 1-phosphorester groups on lipid A. The 3-atom length of the Dab side chains act to maintain the optimal distance between the positive charges and the two negatively charged phosphorester groups. The molecular model of the DPmB3-LPS complex suggests most of the hydrophobic contacts between the peptide component and LPS are maintained, however, the electrostatic contact with the 1-phosphorester group is hampered by the bulky [Dansyl-Lys]1 substitution (Figure 5B). Therefore, in line with the ITC data, the model indicates the DPmB3-LPS complex is largely stabilized by hydrophobic contacts.

Figure 5.

Molecular models of (A) the PmB-LPS complex determined from NMR restraints [36] and (B) the hypothetical DPmB3-LPS complex.

Discussion

The resurgence of polymyxins for the treatment of MDR Gram-negative infections [39] has led to the inevitable development of resistance to this last-line agent, prompting urgent efforts to advance our knowledge of the mechanisms of polymyxin action and resistance. To broaden our understanding of the initial binding of polymyxins to LPS, the DPmB fluorescence assay theoretically offers an inexpensive and simple method of quantitatively describing the interaction. Moreover, given the urgent need for the development of new antimicrobials against emerging Gram-negative ‘superbugs,’ this assay may serve as a platform for screening polymyxin analogs and novel compounds that target LPS [38]. This study aimed to comprehensively explore the structural and mechanistic aspects of this probe, with the end-point of developing a minimally dansylated PmB analog exhibiting properties that closely resemble the parent compound, PmB.

MS was utilized to examine the extent of dansylation of the diaminobutyric acid side chains; analysis of semi-synthetic DPmB preparations and commercial DPmB revealed the existence of mono-, di-, tri-, and tetra-substituted PmB. Furthermore, as PmB comprises two major components (PmB1 and PmB2) [40], the potential for either of these components to be substituted at any of the five γ-amino groups with up to four dansyl molecules results in a highly variable mixture of dansylated derivatives. Indeed, complexities associated with the use of these preparations to probe specific polymyxin binding properties are thus evident. Here we have obtained DPmB3, which is mono-substituted with a single dansyl moiety at the terminal Dab1 residue position situated within the linear tri-peptide segment of the PmB scaffold (Figure 1). In stark contrast to the first reported semi-synthesis of DPmB [18]), our fully synthetic DPmB3 was devoid of antimicrobial activity. One possible explanation for this discrepancy is that the early preparation procedure did not involve HPLC purification of the products, and possibly contained residual PmB. It is understood that several MDR Gram-negative pathogens resist the action of polymyxins by modifications of LPS which reduce the negative surface charge. The most common mechanism involves esterification of lipid A phosphates with 4-amino-4-deoxy-L-arabinose, or ethanolamine, which shields crucial interactions with the protonated Dab side chains of polymyxins [41; 42; 43]. It was therefore of no surprise that the loss of this vital electrostatic interaction through the steric bulk of the hydrophobic dansyl[Lys]1 substitution imparted a complete loss of PmB antibacterial activity.

The pKa of the dimethylamino group in the dansyl moiety in water or when attached to a small molecule is ~3.6 [44]. Protonation quenches its fluorescence [45; 46]. Therefore, at the buffer pH employed for the LPS binding experiments, the dimethylamino group will be largely in the unprotonated form, which also coincides with the low intrinsic fluorescence of DPmB3 in buffer alone.

Fluorometric titrations with DPmB3 into LPS from various Gram-negative bacterial species revealed a comparable binding affinity to PmB and colistin, whereas the semi-synthetic preparations displayed a substantially lower affinity (Table 1). These findings clearly demonstrate that the coupling of multiple bulky dansyl groups inactivate the positive Dab side chains, and introduce considerable steric hindrance resulting in a marked decrease in LPS binding capability. The fluorometric displacement data showed PmB and colistin displayed a lower binding affinity for P. aeruginosa LPS compared to the LPS from other Gram-negative species (Table 1). In comparison, DPmB3 displayed a higher affinity than PmB and colistin for P. aeruginosa LPS. When compared to LPS from other Gram-negative species, the LPS of P. aeruginosa displays shorter length fatty acyl chains on its lipid A component [42] (Table 1). Such differences may confer alterations to outer membrane fluidity, and the organization of lipid A molecules within the cell envelope which in turn may alter the accessibility of specific sites for polymyxin binding. One possibility is that the reduction in hydrophobic surface area on the P. aeruginosa LPS available for binding to the N-terminal fatty acyl chain of PmB and colistin, led to a reduced binding affinity. With this possibility, the addition of the hydrophobic dansyl group to the PmB scaffold may have had a compensatory effect, by increasing the hydrophobic surface area for interaction with the lipid A fatty acyl chains, thereby increasing the binding affinity. This postulate is in line with the ITC data that revealed a greater entropic contribution for DPmB3-LPS binding compared to the PmB-LPS interaction (Table 1).

PBN is an inactive derivative of PmB, produced by proteolytic cleavage of the terminal Dab amino acid residue and N-fatty acyl chain (Figure 1). The negligible antibacterial activity of PBN may be attributed to its inability to establish hydrophobic membrane contacts [47; 48]. Thus, owing to the preservation of its cationic nature, PBN presents an ideal candidate to investigate the electrostatic interaction of polymyxins with LPS. PBN displayed the lowest binding affinity for LPS in comparison to the other polymyxins, indicating the N-terminal fatty acyl chain and structural amphipathicity are essential for high affinity interactions with LPS.

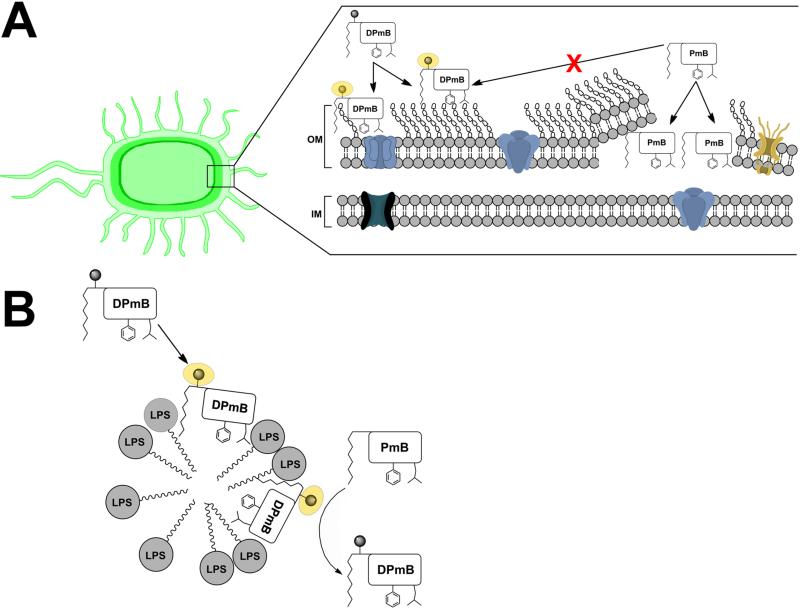

Isolated LPS molecules aggregate into micelles within an aqueous environment [49; 50] (Figure 6B), presenting a defined system whereby negatively charged polymyxin binding sites are directly accessible for interactions to ensue. However, this model does not accurately represent the true binding of polymyxins to the Gram-negative outer membrane. With this in mind, the substantially reduced affinity of DPmB3 for whole bacterial cells in comparison to LPS (Table 1) is understandable, as in whole-cell systems, specific binding interactions between DPmB3 and LPS are likely to be competing with non-specific interactions between DPmB3 and various other membrane constituents (Figure 6A) [8]. Indeed for colistin-resistant A. baumannii cells which are believed to lack LPS completely (manuscript returned for revision), attraction to the outer membrane must arise entirely from interactions with other surface molecules. Binding to these alternative sites on colistin-resistant membranes is likely to occur with reduced efficiency than binding to LPS; this may account for the reduced DPmB3 affinity noted for colistin-resistant A. baumannii in comparison to their parent -susceptible cells.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagrams of the putative binding mechanism of DPmB3 to the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria and LPS micelles. (A) The Gram-negative bacterial outer membrane is composed of an outer leaflet of LPS and an inner leaflet of phospholipids. The inner membrane is composed of a phospholipid bilayer. Transmembrane proteins such as porins are within both outer- and inner-membrane structures. Our data suggest the interaction of DPmB3 with the outer membrane differs markedly compared to the interaction characteristics of native PmB. This may account for the lack of antimicrobial activity of DPmB3 and the inability of PmB to displace all DPmB3 fluorescence bound to the outer membrane of whole cells. (B) DPmB3 displays saturable and specific binding to LPS micelles analogous to the binding characteristics of PmB. DPmB3 is effectively displaced from the LPS binding sites by titration with unlabelled PmB, which is seen as a decrease in fluorescence emission.

Attempts to quantify PmB and colistin affinity for whole cells by competitive displacement titrations were not successful, as the reduction in fluorescence did not plateau upon successive additions of competing PmB or colistin. Although events following polymyxin uptake through the Gram-negative outer membrane are not completely characterized in the literature, an osmotic imbalance is believed to lead to lysis and cell death [15; 51]. Thus, one possibility is that DPmB3 simply binds to additional non-specific sites on the heterogeneous outer membrane surface as well as released intracellular material, with greater affinity than PmB leading to continued fluorescence (Figure 6A).

Brandenburg et al. demonstrated a temperature dependence of PmB-LPS calorimetric titration curves on the phase state of LPS [52]. An endothermic reaction was observed when calorimetric titrations of PmB into isolated LPS from polymyxin-susceptible strains of Salmonella minnesota and Salmonella abortus equi were performed at temperatures ≤30°C (below the acyl chain phase transition temperature, Tc of LPS). Under these conditions, the fatty acyl chains of LPS are in the gel phase. Whereas titrations performed above the phase transition temperature (≥35°C for LPS) displayed exothermic binding enthalpies [52; 53], where the acyl chains are in the liquid crystalline phase. In contrast, the reaction remained endothermic even above the Tc for LPS isolated from polymyxin-resistant strain of Proteus mirabilis [54]. Accordingly, our ITC experiments were performed exclusively at the physiologically relevant temperature of 37°C. Microcalorimetric titrations with PmB and DPmB3 into E. coli LPS revealed both reactions were exothermic, which can be interpreted to evolve from the strong electrostatic interaction of the positively charged Dab amine groups of the polymyxin peptides with the negative charges of LPS. The calorimetric enthalpy change for both the PmB- and DPmB3-LPS interactions conformed well to a model which describes two sets of independent binding sites. The derived microscopic thermodynamic parameters for the PmB-LPS reaction indicate the first phase of the reaction is driven by a combination of enthalpic and entropic forces, reflective of the electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions involved in PmB-LPS complexation [55]. The second phase is more complex and is associated with an unfavorable entropic change.

Similarly, both phases of the DPmB3-LPS reaction are largely driven by enthalpic forces, however both phases are also accompanied by unfavourable entropic changes. This may be reflective of the hydrophobic dansyl substituent which strongly contributes to apolar interactions with the lipid A fatty acyl chains. This would suggest DPmB3 is capable of significantly affecting the LPS assembly. Thus, the loss of entropy possibly reflects a decrease in fluidity of the LPS fatty acyl chains due to aggregation or supramolecular structure formation with DPmB3 [56]. Moreover, these effects may be accentuated at the high LPS concentrations (125 μM) employed for the ITC experiments in comparison to the low concentrations (150 nM) used in the fluorometric titrations, which may explain the differences in binding characteristics observed between the two methods. The superposition of all these three effects may account for the very complex ITC titration curves. Taken together the microscopic thermodynamic parameters indicate the PmB- and DPmB3-LPS interactions follow markedly different mechanisms under the ITC experimental conditions.

The dansyl moiety incorporates a bi-phenyl structure, together with a sulphonamide group which conveys considerable electron withdrawing properties and adds substantial bulk to the molecule. Modifications to the overall charge distribution are thus expected to arise, which will impact the establishment of electrostatic contacts between DPmB3 and LPS or whole cells. Molecular modelling of the DPmB3-LPS complex indicated that electrostatic interactions with the 1-phosphoester group on lipid A are hampered by the bulky dansyl group (Figure 5B). The model further suggests the hydrophobic dansyl group interacts with the apolar environment formed by the fatty acyl chains of lipid A. This would account for the enhanced fluorescence emission observed upon LPS binding. Indeed, the combination of these factors may compromise the ability of DPmB3 to associate exclusively with the exact sites on LPS/whole cells which bind PmB.

Conclusions

In summary, semi-synthetic DPmB popularly employed in the literature to investigate the binding affinity of polycationic compounds, is poly-substituted with dansyl groups. Despite extensive use, our study has first revealed structural complexities and mechanistic inadequacies associated with the DPmB assay. Our mono-substituted DPmB3 presents an improved probe for this fluorescent assay. From a drug screening perspective, the DPmB3 assay is thus of considerable utility in medicinal chemistry programs aimed at developing the next generation of polymyxin antibiotics, which are so desperately needed for Gram-negative ‘superbugs’ in this era.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Scheme 1 Generalized scheme for peptide synthesis of DPmB3.

Supplementary Figure 2. (A) HPLC chromatogram of DPmB3 and (B) MALDI-TOF spectra of HPLC purified DPmB3.

Supplementary Figure 3.1. LC/MS/MS chromatograms of dansylation products of polymyxin B1. (A) monodansylated, (B) didansylated, (C) tridansylated and (D) quadruple dansylated products.

Supplementary Figure 3.2. LC/MS/MS chromatograms of dansylation products of polymyxin B2. (A) monodansylated, (B) didansylated, (C) tridansylated and (D) quadruple dansylated products.

Supplementary Figure 3.3. Precursor scan mass spectra of dansylation products of polymyxin B1 and B2 acquired in the presence of 0.1% formic acid. (A) triple-charged molecular ions of mono to quadruple dansylated polymyxin B1 generated from the fragment at m/z 223, (B) triple-charged molecular ions of mono to quadruple dansylated polymyxin B2 generated from the fragment at m/z 209.

Supplementary Figure 3.4. MS/MS spectra of double-charged monodansylated polymyxin B1 and B2 acquired in 1:1 acetontirle / 0.1 M ammonium formate. (A) monodansylated polymyxin B1 [M+2H] 2+ at m/z 719, (B) monodansylated polymyxin B [M+2H] 2+ 2 at m/z 712.

Supplementary Figure 3.5. MS/MS spectra of double-charged didansylated polymyxin B1 and B2 acquired in 1:1 acetonitrile / 0.1 M ammonium formate. (A) didansylated polymyxin B1 [M+2H] 2+ at m/z 836, (B) didansylated polymyxin B2 [M+2H] 2+ at m/z 829.

Supplementary Figure 3.6. Diagnostic CID pathway of polymyxin B1 and B2 and their dansylated products. For dansylated Dab 1 products, b fragment ions at m/z 474 and 460 were observed for polymyxin B1 and B2, respectively. For products not dansylated at Dab 1, y fragment ions with the loss of the acyl-Dab were found.

Acknowledgements

R.L.N. and J.L. are supported by research grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (R01A1070896 and R01AI079330). R.L.N., J.L., P.E.T. and T.V. are also supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases or the National Institutes of Health. J.L. is an Australian NHMRC R. Douglas Wright Research Fellow.

Abbreviations

- LPS

lipopolysaccharid

- PmB

polymyxin B

- DPmB

semi-synthetic dansyl-polymyxinB

- DPmB3

dansyl[Lys]1polymyxinB3

- PBN

polymyxin B nona-peptide

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Fischbach MA, Walsh CT. Antibiotics for emerging pathogens. Science. 2009;325:1089–93. doi: 10.1126/science.1176667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Boucher HW, Talbot GH, Bradley JS, Edwards JE, Gilbert D, Rice LB, Scheld M, Spellberg B, Bartlett J. Bad bugs, no drugs: no ESKAPE! An update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1–12. doi: 10.1086/595011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Nation RL, Li J. Colistin in the 21st century. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2009;22:535–543. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328332e672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Suh YD, Son JS, Chung DR, Peck KRR, So KS, Song JH. Nonclonal emergence of colistin-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from blood samples in South Korea. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:560–2. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00762-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hernan RC, Karina B, Gabriela G, Marcela N, Carlos V, Angela F. Selection of colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates in postneurosurgical meningitis in an intensive care unit with high presence of heteroresistance to colistin. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;65:188–91. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2009.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Park YK, Jung SI, Park KH, Cheong HS, Peck KR, Song JH, Ko KS. Independent emergence of colistin-resistant Acinetobacter spp. isolates from Korea. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;64:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cabeen MT, Jacobs-Wagner C. Bacterial cell shape. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:601–610. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Nikaido H. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability revisited. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2003;67:593–656. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.593-656.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Raetz CR, Whitfield C. Lipopolysaccharide endotoxins. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:635–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Storm DR, Rosenthal KS, Swanson PE. Polymyxin and related peptide antibiotics. Annu Rev Biochem. 1977;46:723–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.46.070177.003451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Schindler M, Osborn MJ. Interaction of divalent cations and polymyxin B with lipopolysaccharide. Biochemistry. 1979;18:4425–30. doi: 10.1021/bi00587a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Peterson AA, Hancock REW, McGroarty EJ. Binding of polycationic antibiotics and polyamines to lipopolysaccharides of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1985;164:1256–61. doi: 10.1128/jb.164.3.1256-1261.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Katz M, Tsubery H, Kolusheva S, Shames A, Fridkin M, Jelinek R. Lipid binding and membrane penetration of polymyxin B derivatives studied in a biomimetic vesicle system. Biochem J. 2003;375:405–13. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wiese A, Munstermann M, Gutsmann T, Lindner B, Kawahara K, Zahringer U, Seydel U. Molecular mechanisms of polymyxin B-membrane interactions: direct correlation between surface charge density and self-promoted transport. J Membr Biol. 1998;162:127–38. doi: 10.1007/s002329900350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hancock REW, Chapple DS. Peptide Antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1317–1323. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.6.1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Saugar JM, Rodriguez-Hernandez MJ, de la Torre BG, Pachon-Ibanez ME, Fernandez-Reyes M, Andreu D, Pachon J, Rivas L. Activity of cecropin A-melittin hybrid peptides against colistin-resistant clinical strains of Acinetobacter baumannii: molecular basis for the differential mechanisms of action. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:1251–1256. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.4.1251-1256.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Moore R, Bates N, Hancock R. Interaction of polycationic antibiotics with Pseudomonas aeruginosa lipopolysaccharide and lipid A studied by using dansyl-polymyxin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986;29:496–500. doi: 10.1128/aac.29.3.496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Schindler PR, Teuber M. Action of polymyxin B on bacterial membranes: morphological changes in the cytoplasm and in the outer membrane of Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli B. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1975;8:95–104. doi: 10.1128/aac.8.1.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Teuber M, Bader J. Action of polymyxin B on bacterial membranes. Binding capacities for polymyxin B of inner and outer membranes isolated from Salmonella typhimurium G30. Arch Microbiol. 1976;109:51–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00425112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].David SA, Balasubramanian KA, Mathan VI, Balaram P. Analysis of the binding of polymyxin B to endotoxic lipid A and core glycolipid using a fluorescent displacement probe. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1165:147–52. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(92)90180-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Tsubery H, Ofek I, Cohen S, Fridkin M. The functional association of polymyxin B with bacterial lipopolysaccharide is stereospecific: studies on polymyxin B nonapeptide. Biochemistry. 2000;39:11837–11844. doi: 10.1021/bi000386q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Hancock RE, Farmer SW. Mechanism of uptake of deglucoteicoplanin amide derivatives across outer membranes of Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:453–456. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.3.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Campos MA, Morey P, Bengoechea JA. Quinolones sensitize Gram-negative bacteria to antimicrobial peptides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:2361–2367. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01437-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Moore RA, Chan L, Hancock RE. Evidence for two distinct mechanisms of resistance to polymyxin B in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1984;26:539–45. doi: 10.1128/aac.26.4.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Rivera M, Hancock RE, Sawyer JG, Haug A, McGroarty EJ. Enhanced binding of polycationic antibiotics to lipopolysaccharide from an aminoglycoside-supersusceptible, tolA mutant strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32:649–655. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.5.649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Arcidiacono S, Soares JW, Meehan AM, Marek P, Kirby R. Membrane permeability and antimicrobial kinetics of cecropin P1 against Escherichia coli. J Pept Sci. 2009;15:398–403. doi: 10.1002/psc.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Danner RL, Joiner KA, Rubin M, Patterson WH, Johnson N, Ayers KM, Parrillo JE. Purification, toxicity, and antiendotoxin activity of polymyxin B nonapeptide. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:1428–34. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.9.1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Westphal O, Jann K. Bacterial lipopolysaccharides: extraction with phenol-water and further applications of the procedure. Academic Press Inc.; New York: 1965. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Dubray G, Bezard G. A highly sensitive periodic acid-silver stain for 1,2-diol groups of glycoproteins and polysaccharides in polyacrylamide gels. Anal Biochem. 1982;119:325–9. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90593-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute . Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: Seventeenth Informational Supplement M100-S17. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; Wayne, PA., Wayne, PA, USA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Vaara M, Fox J, Loidl G, Siikanen O, Apajalahti J, Hansen F, Frimodt-Moller N, Nagai J, Takano M, Vaara T. Novel polymyxin derivatives carrying only three positive charges are effective antibacterial agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:3229–3236. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00405-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Schindler PRG, Teuber M. Action of polymyxin B on bacterial membranes: morphological changes in the cytoplasm and in the outer membrane of Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli B. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1975;8:95–104. doi: 10.1128/aac.8.1.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Origin 8 User Guide. OriginLab Corporation; Northampton, MA: 2007. http://www.llas.ac.cn/upload/Origin_8_User_Guide.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Marquardt D. An algorithm for least-squares estimation of nonlinear parameters. SIAM J Appl Math. 1963;11:431–441. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Pristovsek P, Kidric J. The search for molecular determinants of LPS inhibition by proteins and peptides. Curr Top Med Chem. 2004;4:1185–201. doi: 10.2174/1568026043388105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ferguson AD, Welte W, Hofmann E, Lindner B, Holst O, Coulton JW, Diederichs K. A conserved structural motif for lipopolysaccharide recognition by procaryotic and eucaryotic proteins. Structure. 2000;8:585–92. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00143-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Velkov T, Thompson PE, Nation RL, Li J. Structure-activity relationships of polymyxin antibiotics. J Med Chem. 2010;53:1898–916. doi: 10.1021/jm900999h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Li J, Nation RL, Turnidge JD, Milne RW, Coulthard K, Rayner CR, Paterson DL. Colistin: the re-emerging antibiotic for multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:589–601. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70580-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Orwa JA, Govaerts C, Busson R, Roets E, Van Schepdael A, Hoogmartens J. Isolation and structural characterization of polymyxin B components. J Chromatogr. 2001;912:369–373. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)00585-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Gatzeva-Topalova PZ, May AP, Sousa MC. Crystal structure of Escherichia coli ArnA (PmrI) decarboxylase domain. A key enzyme for lipid A modification with 4-amino-4-deoxy-L-arabinose and polymyxin resistance. Biochemistry. 2004;43:13370–9. doi: 10.1021/bi048551f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Moskowitz SM, Ernst RK, Miller SI. PmrAB, a two-component regulatory system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa that modulates resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides and addition of aminoarabinose to lipid A. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:575–9. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.2.575-579.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Knirel YA, Dentovskaya SV, Bystrova OV, Kocharova NA, Senchenkova SN, Shaikhutdinova RZ, Titareva GM, Bakhteeva IV, Lindner B, Pier GB, Anisimov AP. Relationship of the lipopolysaccharide structure of Yersinia pestis to resistance to antimicrobial factors. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;603:88–96. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-72124-8_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Seki T, Akimoto T, Iijima T. The effect of the N-B transition of bovine and human serum albumins on the binding sites of fluorescent probes. Colloid Polym Sci. 1987;265:148–54. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Klotz IM, Fiess HA. Ionic equilibria in a protein conjugate of a sulfonamide type. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1960;38:57–63. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(60)91195-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Young M. On the titration behavior of dimethylaminonaphthalene-protein conjugates. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1963;71:206–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(63)91007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Tsubery H, Ofek I, Cohen S, Fridkin M. N-terminal modifications of Polymyxin B nonapeptide and their effect on antibacterial activity. Peptides. 2001;22:1675–81. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(01)00503-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Meredith JJ, Dufour A, Bruch MD. Comparison of the structure and dynamics of the antibiotic peptide polymyxin B and the inactive nonapeptide in aqueous trifluoroethanol by NMR spectroscopy. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:544–51. doi: 10.1021/jp808379x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Aurell CA, Wistrom AO. Critical aggregation concentrations of Gram-negative bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS) Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;253:119–23. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Yu L, Tan M, Ho B, Ding JL, Wohland T. Determination of critical micelle concentrations and aggregation numbers by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy: aggregation of a lipopolysaccharide. Anal Chim Acta. 2006;556:216–25. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Oh JT, Van Dyk TK, Cajal Y, Dhurjati PS, Sasser M, Jain MK. Osmotic stress in viable Escherichia coli as the basis for the antibiotic response by polymyxin B. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;246:619–23. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Brandenburg K, David A, Howe J, Michel H.J. Koch, Andra J, Garidel P. Temperature dependence of the binding of endotoxins to the polycationic peptides polymyxin B and its nonapeptide. Biophys J. 2005;88:1845–58. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.047944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Koch P, Frank J, Schuler J, Kahle C, Bradaczek H. Thermodynamics and structural studies of the interaction of polymyxin B with peep rough mutant lipopolysaccharides. J Colloid Interface Sci. 1999;213:557–564. doi: 10.1006/jcis.1999.6137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Howe J, Andrae J, Conde R, Iriarte M, Garidel P, Koch MHJ, Gutsmann T, Moriyon I, Brandenburg K. Thermodynamic analysis of the lipopolysaccharide-dependent resistance of Gram-negative bacteria against polymyxin B. Biophys J. 2007;92:2796–2805. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.095711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Pristovsek P, Kidric J. Solution structure of polymyxins B and E and effect of binding to lipopolysaccharide: an NMR and molecular modeling study. J Med Chem. 1999;42:4604–13. doi: 10.1021/jm991031b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Clausell A, Pujol M, Alsina MA, Cajal Y. Influence of polymyxins on the structural dynamics of Escherichia coli lipid membranes. Talanta. 2003;60:225–34. doi: 10.1016/S0039-9140(03)00078-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Raetz CR. E. coli and Salmonella. American Society of Microbiology; Washington, D.C: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- [58].Clements A, Tull D, Jenney AW, Farn JL, Kim S-H, Bishop RE, McPhee JB, Hancock REW, Hartland EL, Pearse MJ, Wijburg OLC, Jackson DC, McConville MJ, Strugnell RA. Secondary acylation of Klebsiella pneumoniae lipopolysaccharide contributes to sensitivity to antibacterial peptides. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:15569–15577. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701454200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Zhou Z, Ribeiro AA, Lin S, Cotter RJ, Miller SI, Raetz CR. Lipid A modifications in polymyxin-resistant Salmonella typhimurium: PMRA-dependent 4-amino-4-deoxy-L-arabinose, and phosphoethanolamine incorporation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:43111–21. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106960200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Scheme 1 Generalized scheme for peptide synthesis of DPmB3.

Supplementary Figure 2. (A) HPLC chromatogram of DPmB3 and (B) MALDI-TOF spectra of HPLC purified DPmB3.

Supplementary Figure 3.1. LC/MS/MS chromatograms of dansylation products of polymyxin B1. (A) monodansylated, (B) didansylated, (C) tridansylated and (D) quadruple dansylated products.

Supplementary Figure 3.2. LC/MS/MS chromatograms of dansylation products of polymyxin B2. (A) monodansylated, (B) didansylated, (C) tridansylated and (D) quadruple dansylated products.

Supplementary Figure 3.3. Precursor scan mass spectra of dansylation products of polymyxin B1 and B2 acquired in the presence of 0.1% formic acid. (A) triple-charged molecular ions of mono to quadruple dansylated polymyxin B1 generated from the fragment at m/z 223, (B) triple-charged molecular ions of mono to quadruple dansylated polymyxin B2 generated from the fragment at m/z 209.

Supplementary Figure 3.4. MS/MS spectra of double-charged monodansylated polymyxin B1 and B2 acquired in 1:1 acetontirle / 0.1 M ammonium formate. (A) monodansylated polymyxin B1 [M+2H] 2+ at m/z 719, (B) monodansylated polymyxin B [M+2H] 2+ 2 at m/z 712.

Supplementary Figure 3.5. MS/MS spectra of double-charged didansylated polymyxin B1 and B2 acquired in 1:1 acetonitrile / 0.1 M ammonium formate. (A) didansylated polymyxin B1 [M+2H] 2+ at m/z 836, (B) didansylated polymyxin B2 [M+2H] 2+ at m/z 829.

Supplementary Figure 3.6. Diagnostic CID pathway of polymyxin B1 and B2 and their dansylated products. For dansylated Dab 1 products, b fragment ions at m/z 474 and 460 were observed for polymyxin B1 and B2, respectively. For products not dansylated at Dab 1, y fragment ions with the loss of the acyl-Dab were found.