Abstract

Aims

To assess the relationship between regulated on activation, normal T-cell expressed and secreted (RANTES) and carotid atherosclerotic plaque burden and plaque characteristics.

Methods and results

Gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the carotid artery was performed in 1901 participants from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Wall thickness and volume, lipid-core volume, and fibrous cap thickness (by MRI) and plasma RANTES levels (by ELISA) were measured. Regression analysis was performed to study the associations between MRI variables and RANTES. Among 1769 inclusive participants, multivariable regression analysis revealed that total wall volume [beta-coefficient (β) = 0.09, P = 0.008], maximum wall thickness (β = 0.08, P = 0.01), vessel wall area (β = 0.07, P = 0.02), mean minimum fibrous cap thickness (β = 0.11, P = 0.03), and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (β = 0.09, P = 0.01) were positively associated with RANTES. Total lipid-core volume showed positive association in unadjusted models (β = 0.18, P = 0.02), but not in fully adjusted models (β = 0.13, P = 0.09). RANTES levels were highest in Caucasian females followed by Caucasian males, African-American females, and African-American males (P < 0.0001). Statin use attenuated the relationship between RANTES and measures of plaque burden.

Conclusion

Positive associations between RANTES and carotid wall thickness and lipid-core volume (in univariate analysis) suggest that higher RANTES levels may be associated with extent of carotid atherosclerosis and high-risk plaques. Associations between fibrous cap thickness and RANTES likely reflect the lower reliability estimate for fibrous cap measurements compared with wall volume or lipid-core volume measurements. Statin use may modify the association between RANTES and carotid atherosclerosis. Furthermore, RANTES levels vary by race.

Keywords: Atherosclerosis, Magnetic resonance imaging, Inflammation, RANTES, High-sensitivity C-reactive protein

See page 393 for the editorial comment on this article (doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehq376)

Introduction

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disorder, and its initiation and progression is controlled by various mediators of inflammation.1,2 Chemokines play a significant role in this inflammatory cascade.1 Platelets have been shown to be an important source of chemokines and to play a role in the process of inflammation.3

CC chemokine ligand-5, or regulated on activation, normal T-cell expressed, and secreted (RANTES), is a CC chemokine that is expressed by cell types such as T-cells, fibroblasts, and mesangial cells3 and also stored in the alpha granules of platelets.4 After release from the activated platelets, RANTES is deposited onto endothelium via interactions with specific chemokine receptors (CCR1, CCR3, CCR4, and CCR5)5,6 and has been shown to mediate transmigration of monocytes and T-cells into the intima.7–9 RANTES also acts as a T-cell mitogen and induces the release of pro-inflammatory mediators.10,11 RANTES is highly expressed in atheroma and has been implicated in the atherosclerotic disease process.12

Data regarding clinical significance of RANTES in atherosclerosis and its role in plaque vulnerability remain controversial. In some studies, especially those involving patients with acute coronary syndromes, levels of RANTES have been found to be elevated,13 whereas in other studies, low levels of RANTES have been shown to be independently predictive of adverse cardiac outcomes in patients with chronic coronary artery disease.14

Since RANTES is known to be a very potent chemo-attractant for a variety of cell types including T-cells and monocytes,15 it is possible that high levels of RANTES would lead to a more cellular infiltrate in the plaques. This process may lead to initiation and progression of atherosclerosis. In addition, vulnerable plaques are known to be characterized by a prominent lipid core, thin fibrous caps, and a large number of macrophages.16 Higher than normal levels of RANTES may lead to recruitment of more macrophages into the plaque, which in turn could secrete matrix metalloproteinases,17 leading to a breakdown of the fibrous cap, making these plaques unstable or vulnerable.

The primary aim of this analysis was to assess the relationship of plasma RANTES levels with total atherosclerotic plaque burden. A secondary aim was to assess the relationship between RANTES levels and markers of high-risk plaques (i.e. plaques with lipid-rich cores and thin fibrous caps). We hypothesized that high plasma RANTES levels would be associated with an increased carotid plaque burden and high-risk plaques. We also aimed to assess the relationship between plasma RANTES levels and the inflammatory biomarker high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, and hypothesized that high plasma RANTES levels would be associated with elevated levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein.

Methods

The study methods for the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study have been described previously;18 relevant text is described here. A separate manuscript pertaining to ARIC MRI Study methodology is also attached as a supplement. The study sample consisted of 2066 members of the ARIC study cohort who participated in the ARIC Carotid MRI substudy in 2004–2005 (year 18). The ARIC study is a population-based cohort study of cardiovascular disease incidence among African-American and Caucasian adults (n = 15 792). ARIC participants were selected to be representative of adults aged 45–64 years in four communities in the USA.

In order to increase the prevalence of informative plaques while maintaining the ability to make population-based inferences, a stratified sampling plan was used. The goal was to recruit 1200 participants with high values of maximum carotid artery wall thickness (maximum over six sites: left and right, common, bifurcation, internal) at their last ultrasound examination, and 800 individuals were randomly sampled from the remainder of the carotid artery wall thickness distribution. Persons whose race was other than African-American or Caucasian were excluded from the selection process, as were those without carotid intimal medial wall thickness (CIMT) measurements at their last or penultimate examination. Field-centre-specific cutpoints of CIMT were adjusted over the recruitment period to approximately achieve this goal, with 100% sampling above the cutpoint, and a sampling fraction below the cutpoint to achieve the desired 800. Intima–media thickness (IMT) cut-offs were 1.35, 1.00, 1.28, and 1.22 mm in Forsyth County, Jackson, Minneapolis, and Washington County, respectively, representing the 73rd, 69th, 73rd, and 68th percentiles of maximal IMT from Exam 4. Recruitment lists were provided to the field centres, which sampled from above and below the IMT cutpoint as indicated by the sampling plan. Lists included an indicator for which carotid, left or right, had the greatest CIMT. Ineligibility criteria for the Carotid MRI substudy included standard contraindications to the MRI exam or to the contrast agent, carotid revascularization on either side for the low CIMT group or on the side selected for imaging for the high CIMT group, and difficulties in understanding questions or in completing the informed consent. A total of 4306 persons were contacted and invited to participate in the Carotid MRI substudy, and 1403 refused, 837 were ineligible, and 2066 participated. The overall recruitment rates were 41, 48, 51, and 53% of all persons contacted, across the four centres, with little difference in rates between high and low CIMT groups. Of the 2066 ARIC cohort members who participated in the Carotid MRI substudy, 1901 had a complete MRI exam, of which 1769 had sufficient quality of MRI scans and adherence to MRI protocol to be included for analyses.

Participant examination

Protocols for lipoprotein, fasting glucose, blood pressure, height and weight measurements were identical at the baseline ARIC cohort examination and 18 years later at the Carotid MRI substudy examination. The study was approved by the institutional review committees of all participating centres, and all participants provided informed consent.

RANTES measurement

Plasma samples were collected on ice using EDTA as the anticoagulant. All collected samples were centrifuged for 20 min at 4°C at 2800g within 30 min of collection. Plasma RANTES levels were quantitatively measured using Quantikine® human RANTES immunoassay (R&D systems Inc, Minneapolis, MN, USA). This assay employs a quantitative sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay technique with a reported detection limit for human RANTES of 2.0 pg/ml.

In the current study, the RANTES assay had an intra-assay variation coefficient of 4.1% and an inter-assay variation coefficient of 7.3%. The reliability coefficient (r) for the RANTES assay was 0.75 based on 112 blinded replicate samples.

MRI protocol

The methods for acquisition and interpretation of the Carotid MRI substudy have been described previously.18 A separate manuscript pertaining to ARIC MRI Study methodology is attached to this manuscript as a supplement (see also Figure 1). A contrast-enhanced MRI exam of the thickest 1.6 cm segment of the thicker carotid artery was performed according to a standard protocol. Each MRI study was acquired on a 1.5 T whole-body scanner. A three-dimensional time-of-flight magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) was acquired through both carotid bifurcations. Detailed black blood MRI (BBMRI) images were then acquired through the extracranial carotid bifurcation, known to have a thicker maximum wall by the most recent ultrasound study, unless the contralateral carotid bifurcation wall appeared to the technologist to be thicker on the MRA.

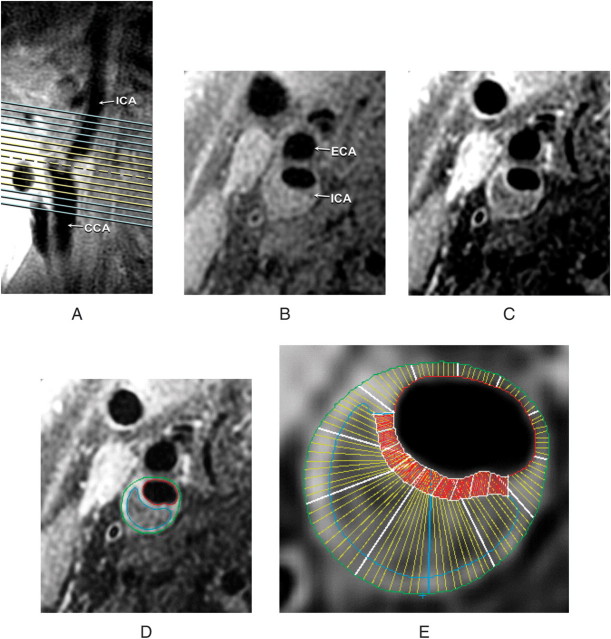

Figure 1.

Black blood MRI (BBMRI) slices through the carotid bifurcation and plaque. A long-axis BBMRI image adjacent to the slice shown in (A) was used to orient eight pre-contrast (yellow lines) and 16 post-contrast (yellow and blue lines) slices through the plaque. Transverse BBMRI image through the thickest part of the plaque (A, broken line) is shown before (B) and after (C) contrast administration. Contours were drawn on the post-contrast image to delineate the core (blue), lumen (red) and outer wall (green) (D). The wall was automatically divided into 12 radial segments and the cap was segmented at 15° increments (E). Segmental thickness measurements were determined by averaging the yellow line thicknesses for the wall and red line thicknesses for the cap (E). This figure shows how the images were acquired as well as how wall thickness and fibrous cap thickness were measured.

Sixteen axial T1-weighted, fat-suppressed BBMRI slices (thickness, 2 mm; acquired in-plane resolution, 0.51 × 0.58 mm2; total longitudinal coverage, 3.2 cm) were oriented perpendicular to the vessel and centred at the thickest part of the internal or common carotid artery wall. These 16 slices were acquired 5 min after the intravenous injection of gadodiamide (Omniscan, GE Amersham), 0.1 mmol/kg body weight, with a power injector.

Seven readers were trained to interpret the MRI images and contour the wall components using specialized software (VesselMass, Leiden University Medical Center). Readers were blinded to the characteristics of the study population. Each reader drew contours to delineate the lumen, outer wall, lipid core, and calcification. The fibrous cap contour was automatically generated to approximate the lumen and lipid-core contours. Eight slices centred at the slice with the thickest wall were analysed. All exams were assigned quality scores by the reader based on image quality and protocol adherence; exams that failed were not analysed.

Using semi-automated software, vessel walls were divided into 12 radial segments, and mean thickness values were generated for each segment. The fibrous cap was divided into radial segments at 15° increments, with mean thicknesses generated for each segment. Area measurements were calculated for the lipid-core and calcification contours. Volumetric data were computed by integrating area measurements over all eight slices examined. These measurements are described in Figure 1D and E.

Maximum segmental wall thickness (in mm) was defined as the maximum wall thickness of 12 segments at the slice with the largest lipid contour area. Vessel wall area and lumen area (in cm2) were computed at the slice with the largest mean segmental wall thickness. Volume measurements for total wall volume (in mm3) were computed by integrating area measurements over eight slices. Quantitative lipid-rich core measurements used for this analysis included maximum lipid-rich core area of eight slices (cm2) and total lipid-rich core volume (in mm3) based on the lipid-rich core area measurements of the eight slices. Fibrous cap measurements were described as both the mean and the mean of the two minimum cap thicknesses in two adjacent slices with the largest lipid core.

Statistical methods

All analyses were weighted and appropriately accounted for the stratified random sampling design of the ARIC Carotid MRI substudy. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.1 for descriptive statistics or SUDAAN for domain analysis. Wall thickness and wall volume were analysed in the full data set. Owing to the resolution constraints of the MRI scan, we restricted consideration of lipid core to those 1131 participants whose maximum wall thickness was ≥1.5 mm. Only four lipid cores were excluded using this cutpoint. Measurements of lipid-rich core volume, lipid-rich core area, and fibrous cap thickness were analysed as continuous variables among those participants with a lipid core (n = 542).

Standardized regression coefficients (beta-coefficients) are presented for linear regression models, which have been standardized by 1 SD of exposure and outcome with adjustment for covariates. These beta-coefficients can be interpreted as the number of standard deviation difference in the dependent variable (e.g. total wall volume) as related to a single standard deviation difference in plasma RANTES levels. Covariates used for adjustment included age, race, gender, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, smoking status, body mass index, blood glucose, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, hypertensive medications, cholesterol-lowering medications, aspirin, clopidogrel, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications, diabetic medications, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein. In order to adjust for standard risk factors outside of age, sex, and race, we considered for analysis both concurrent (cross-sectional) measures of risk factors as well as cumulative exposure or rate of change of exposure. The cumulative exposures were determined for continuous variables as the area under the curve of exam-specific values plotted vs. exam time, divided by time between the first and last exam. This can be interpreted as the estimated mean daily value over the period. For dichotomous risk factors, the cumulative indicator is the proportion of time exposed. For the continuous variables, we calculated the rate of change over the period as the person-specific slope from a random coefficients linear model.

Analyses were also performed across RANTES quartiles after adjusting for the above-mentioned covariates to assess whether the carotid MRI variable of interest varied across RANTES quartiles. These analyses were initially performed for the entire cohort. We subsequently performed stratified analyses for different subgroups (African-Americans and Caucasians, statin users vs. non-statin users) using subgroup-specific quartiles for RANTES.

All analyses were performed using two-tailed tests for significance. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The average age of the substudy sample (n = 1769) was 70 years; 57% were female, 81% Caucasian, and 19% African-American. Plasma RANTES levels showed a highly skewed distribution with a mean ± SD of 6930.2 ± 6618.1 pg/mL. The corresponding 25th, 50th, and 75th percentile values for RANTES were 1677.2, 5272.9, and 9785.2 pg/mL, respectively.

Baseline characteristics of participants according to RANTES quartiles are described in Tables 1 and 2. The proportion of African-American participants was larger in lower RANTES quartiles, whereas the proportion of participants who were taking cholesterol-lowering medications and statins was larger in higher RANTES quartiles. Increasing RANTES levels were also associated with a decrease in fasting blood glucose concentration.

Table 1.

Prevalence of baseline categorical variables across RANTES quartiles in the ARIC Carotid MRI Study

| Characteristic (%) | Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 44.0 | 47.6 | 41.3 | 41.4 | 0.38 |

| African-American | 38.1 | 23.6 | 9.7 | 5.3 | <0.0001 |

| Diabetic | 24.2 | 23.6 | 22.8 | 20.5 | 0.73 |

| Hypertensive | 61.6 | 63.6 | 65.3 | 64.2 | 0.81 |

| Current smoker | 10.2 | 5.8 | 8.3 | 7.0 | 0.14 |

| Hypertensive medication use | 63.5 | 65.1 | 64.1 | 59.7 | 0.59 |

| Cholesterol-lowering medication use | 36.4 | 44.9 | 50.1 | 43.4 | 0.008 |

| Statin use | 25.3 | 33.0 | 42.1 | 34.7 | 0.0002 |

| Aspirin use | 61.2 | 66.9 | 69.6 | 69.8 | 0.09 |

| Clopidogrel use | 4.5 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 2.8 | 0.23 |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use | 31.7 | 32.1 | 34.9 | 32.2 | 0.85 |

Table 2.

Weighted means and standard error of means (SE) of continuous variables across RANTES quartiles

| Variablea | Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | P-value for trendb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SE) | 70.6 (0.30) | 70.5 (0.30) | 70.3 (0.31) | 70.0 (0.32) | 0.06 |

| SBP, mmHg, mean (SE) | 123.0 (0.82) | 123.3 (0.77) | 122.8 (0.85) | 121.6 (0.81) | 0.08 |

| DBP, mmHg, mean (SE) | 70.4 (0.45) | 70.3 (0.41) | 70.4 (0.50) | 70.6 (0.47) | 0.64 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SE) | 27.8 (0.25) | 28.1 (0.28) | 27.9 (0.27) | 27.7 (0.26) | 0.541 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL, mean (SE) | 199.5 (1.66) | 201.5 (1.59) | 203.7(1.89) | 204.0 (2.01) | 0.07 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL, mean (SE) | 52.1 (0.86) | 50.4 (0.95) | 52.6 (1.02) | 52.1 (0.95) | 0.64 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL, mean (SE) | 134.7 (4.00) | 135.3 (3.97) | 139.8 (3.80) | 137.9 (3.73) | 0.68 |

| Blood glucose, mg/dL, mean (SE) | 108.5 (1.32) | 107.2 (1.50) | 105.2 (1.34) | 104.0 (1.42) | 0.02 |

| high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, mg/L | 3.75 (0.23) | 3.12 (0.20) | 3.15 (0.20) | 3.82 (0.33) | 0.07 |

SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; BMI, body mass index; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

aAll continuous variables (except age) are presented with time weighted averages across all 5 visits.

bP-values included are results from tests for linear trend.

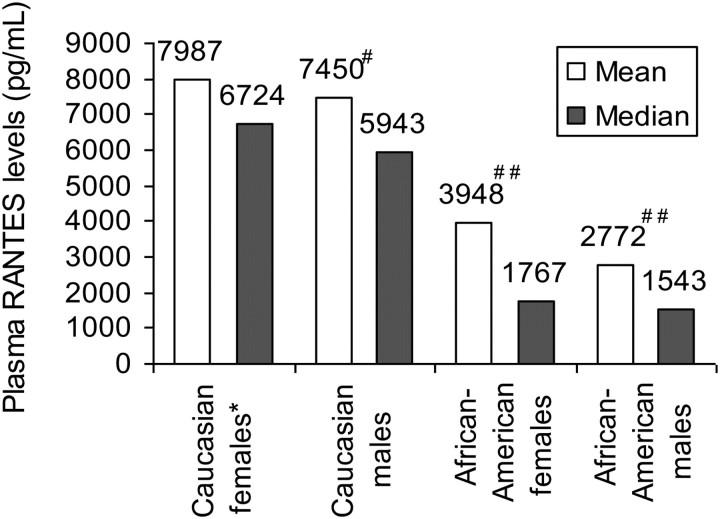

Distribution of plasma RANTES

Plasma RANTES levels showed significant ethnic variations (Figure 2). RANTES levels were highest in Caucasian females, followed by Caucasian males, African-American females, and African-American males (overall P < 0.0001).

Figure 2.

Mean/median plasma RANTES levels across ethnic and gender subgroups in the ARIC Carotid MRI Study (P-value for overall comparison <0.0001). Asterisk, reference group; hash, P = 0.24; double hash, P < 0.0001 compared with Caucasian females. This figure shows how RANTES levels vary by race, with Caucasian participants having higher RANTES levels compared with African-Americans.

Associations between RANTES and measures of carotid atherosclerosis

Carotid MRI variables across RANTES quartiles in the fully adjusted model are described in Table 3. Total carotid wall volume, carotid maximum segmental wall thickness, and carotid vessel wall area increased significantly across increasing RANTES quartiles. No significant linear associations were seen for carotid lumen area, mean fibrous cap thickness, mean of the two minimum fibrous cap thickness in two adjacent slices, total lipid-rich core volume or maximum lipid-core area measurements on eight slices.

Table 3.

Different carotid magnetic resonance imaging variables across RANTES quartiles in the ARIC Carotid MRI Study

| Variablesa | n | RANTES category | Adjusted means (SE) | P-value for difference | Overall P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carotid total wall volume (mm3) | 440 | Q1 (ref) | 0.408 (0.008) | — | 0.023 |

| 430 | Q2 | 0.416 (0.009) | 0.51 | ||

| 394 | Q3 | 0.432 (0.010) | 0.069 | ||

| 386 | Q4 | 0.446 (0.010) | 0.004 | ||

| Carotid maximum segmental wall thickness (mm) | 444 | Q1 (ref) | 1.945 (0.057) | — | 0.015 |

| 429 | Q2 | 2.039 (0.058) | 0.23 | ||

| 393 | Q3 | 2.140 (0.068) | 0.028 | ||

| 386 | Q4 | 2.213 (0.066) | 0.003 | ||

| Carotid vessel wall area (cm2) | 457 | Q1 (ref) | 0.334 (0.008) | — | 0.028 |

| 441 | Q2 | 0.340 (0.008) | 0.540 | ||

| 400 | Q3 | 0.356 (0.009) | 0.063 | ||

| 396 | Q4 | 0.367 (0.009) | 0.006 | ||

| Lumen area (cm2) | 457 | Q1 (ref) | 0.459 (0.014) | — | 0.816 |

| 441 | Q2 | 0.463 (0.012) | 0.848 | ||

| 400 | Q3 | 0.468 (0.012) | 0.620 | ||

| 396 | Q4 | 0.453 (0.011) | 0.75 | ||

| Mean segmental cap thickness of two adjacent slices with largest lipid core (mm) | 159 | Q1 (ref) | 0.641 (0.026) | — | 0.449 |

| 150 | Q2 | 0.681 (0.028) | 0.305 | ||

| 124 | Q3 | 0.663 (0.042) | 0.664 | ||

| 110 | Q4 | 0.720 (0.040) | 0.126 | ||

| Mean of the two minimum fibrous cap thickness in two adjacent slices (mm) | 159 | Q1 (ref) | 0.452 (0.023) | — | 0.300 |

| 150 | Q2 | 0.472 (0.022) | 0.534 | ||

| 124 | Q3 | 0.488 (0.034) | 0.383 | ||

| 110 | Q4 | 0.529 (0.032) | 0.059 | ||

| Total lipid-rich core volume on eight slices (mm3) | 157 | Q1 (ref) | 0.052 (0.007) | — | 0.119 |

| 148 | Q2 | 0.054 (0.006) | 0.794 | ||

| 125 | Q3 | 0.074 (0.012) | 0.082 | ||

| 112 | Q4 | 0.068 (0.008) | 0.145 | ||

| Maximum lipid-core area on eight slices (cm2) | 157 | Q1 (ref) | 0.092 (0.009) | — | 0.156 |

| 148 | Q2 | 0.100 (0.009) | 0.555 | ||

| 125 | Q3 | 0.125 (0.015) | 0.038 | ||

| 112 | Q4 | 0.108 (0.009) | 0.241 |

aCovariates for adjustment include age, gender, race, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, smoking status, body mass index, blood glucose, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, hypertensive medications, cholesterol-lowering medications, aspirin, clopidogrel, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications, diabetic medications, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein.

Table 4 describes the standardized regression coefficients (beta-coefficients) between RANTES levels and carotid MRI variables of interest. Total carotid wall volume, maximum carotid wall thickness, and vessel wall area were positively associated with plasma RANTES levels in fully adjusted models. Total lipid-rich core volume was positively associated with RANTES in the unadjusted model (β = 0.18, P = 0.02, data not shown), but not in fully adjusted models. Mean minimum fibrous cap thickness was also positively associated with increasing RANTES levels. Lumen area and maximum lipid-rich core area were not associated with RANTES, whereas mean fibrous cap thickness showed borderline significant association with RANTES.

Table 4.

Association of (i) carotid magnetic resonance imaging variables and (ii) high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, with plasma levels of RANTES in the fully adjusted model.

| Variable | Beta-coefficienta | P |

|---|---|---|

| Total carotid wall volume (mm3) | 0.09 | 0.008 |

| Maximum carotid wall thickness (mm) | 0.08 | 0.01 |

| Lumen area (cm2) | −0.02 | 0.39 |

| Total lipid-rich core volume (mm3) | 0.13 | 0.09 |

| Maximum lipid-rich core area (cm2) | 0.09 | 0.20 |

| Mean segmental cap thickness (mm) | 0.11 | 0.08 |

| Mean minimum fibrous cap thickness (mm) | 0.11 | 0.03 |

| High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (mg/L)b | 0.09 | 0.01 |

Beta-coefficients and P-values are described for the associations between carotid MRI variables and RANTES levels. Covariates for adjustment include age, gender, race, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, smoking status, body mass index, blood glucose, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, hypertensive medications, cholesterol-lowering medications, aspirin, clopidogrel, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications, diabetic medications, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein.

aBeta-coefficients are standardized regression coefficients and can be interpreted as number of standard deviation difference in the dependent variable (e.g. total wall volume) as related to a 1 SD difference in plasma RANTES levels.

bIncludes all covariates in the adjustment model above except high-sensitivity C-reactive protein.

We performed stratified analyses based on statin use to evaluate whether statins alter the association between RANTES levels and measures of atherosclerosis plaque burden as well as markers of plaque vulnerability (Tables 5and 6). These analyses showed that though RANTES levels were associated with measures of plaque burden in patients not using statins, these associations were attenuated in patients receiving statins. In addition, increasing levels of RANTES were associated with an increase in the total lipid-rich core volumes only in patients not using statins (a finding associated with high-risk plaques).

Table 5.

Different carotid magnetic resonance imaging variables across statin use-specific RANTES quartiles in the ARIC Carotid MRI Study for patients not on statins

| Variablesa | n | RANTES category | Adjusted means (SE) | P-value for difference | Overall P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carotid total wall volume (mm3) | 239 | Q1 (ref) | 0.391 (0.011) | — | 0.0001 |

| 246 | Q2 | 0.398 (0.009) | 0.625 | ||

| 261 | Q3 | 0.427 (0.011) | 0.021 | ||

| 252 | Q4 | 0.451 (0.010) | 0.001 | ||

| Carotid maximum segmental wall thickness (mm) | 239 | Q1 (ref) | 1.808 (0.066) | — | 0.001 |

| 246 | Q2 | 1.912 (0.067) | 0.275 | ||

| 261 | Q3 | 2.093 (0.074) | 0.004 | ||

| 252 | Q4 | 2.192 (0.077) | 0.001 | ||

| Carotid vessel wall area (cm2) | 244 | Q1 (ref) | 0.320 (0.011) | — | 0.008 |

| 256 | Q2 | 0.329 (0.009) | 0.544 | ||

| 266 | Q3 | 0.354 (0.011) | 0.031 | ||

| 258 | Q4 | 0.362 (0.009) | 0.004 | ||

| Lumen area (cm2) | 244 | Q1 (ref) | 0.494 (0.017) | — | 0.117 |

| 256 | Q2 | 0.497 (0.018) | 0.892 | ||

| 266 | Q3 | 0.457 (0.015) | 0.104 | ||

| 258 | Q4 | 0.456 (0.015) | 0.084 | ||

| Mean segmental cap thickness of two adjacent slices with largest lipid core (mm) | 74 | Q1 (ref) | 0.629 (0.035) | — | 0.253 |

| 79 | Q2 | 0.696 (0.038) | 0.182 | ||

| 74 | Q3 | 0.738 (0.067) | 0.150 | ||

| 65 | Q4 | 0.720 (0.045) | 0.109 | ||

| Mean of the two minimum fibrous cap thickness in two adjacent slices (mm) | 74 | Q1 (ref) | 0.442 (0.030) | — | 0.152 |

| 79 | Q2 | 0.499 (0.033) | 0.188 | ||

| 74 | Q3 | 0.524 (0.049) | 0.192 | ||

| 65 | Q4 | 0.522 (0.038) | 0.035 | ||

| Total lipid-rich core volume on eight slices (mm3) | 92 | Q1 (ref) | 0.058 (0.011) | – | 0.018 |

| 79 | Q2 | 0.040 (0.007) | 0.175 | ||

| 60 | Q3 | 0.061 (0.009) | 0.793 | ||

| 61 | Q4 | 0.073 (0.009) | 0.244 | ||

| Maximum lipid-core area on eight slices (cm2) | 92 | Q1 (ref) | 0.099 (0.014) | — | 0.314 |

| 79 | Q2 | 0.085 (0.010) | 0.422 | ||

| 60 | Q3 | 0.107 (0.012) | 0.644 | ||

| 61 | Q4 | 0.108 (0.009) | 0.575 |

aCovariates for adjustment include age, gender, race, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, smoking status, body mass index, blood glucose, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, hypertensive medications, aspirin, clopidogrel , non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications, diabetic medications, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein.

Table 6.

Different carotid magnetic resonance imaging variables across statin use-specific RANTES quartiles in the ARIC Carotid MRI Study for patients taking statins

| Variablesa | n | RANTES category | Adjusted means (SE) | P-value for difference | Overall P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carotid total wall volume (mm3) | 147 | Q1 (ref) | 0.423 (0.013) | — | 0.089 |

| 162 | Q2 | 0.406 (0.013) | 0.359 | ||

| 162 | Q3 | 0.457 (0.018) | 0.110 | ||

| 163 | Q4 | 0.454 (0.019) | 0.192 | ||

| Carotid maximum segmental wall thickness (mm) | 147 | Q1 (ref) | 2.101 (0.105) | — | 0.121 |

| 162 | Q2 | 2.052 (0.091) | 0.733 | ||

| 162 | Q3 | 2.307 (0.131) | 0.204 | ||

| 163 | Q4 | 2.343 (0.106) | 0.107 | ||

| Carotid vessel wall area (cm2) | 153 | Q1 (ref) | 0.346 (0.011) | — | 0.071 |

| 165 | Q2 | 0.336 (0.012) | 0.561 | ||

| 163 | Q3 | 0.371 (0.016) | 0.174 | ||

| 167 | Q4 | 0.385 (0.017) | 0.054 | ||

| Lumen area (cm2) | 153 | Q1 (ref) | 0.461 (0.019) | — | 0.253 |

| 165 | Q2 | 0.441 (0.019) | 0.464 | ||

| 163 | Q3 | 0.443 (0.016) | 0.477 | ||

| 167 | Q4 | 0.415 (0.015) | 0.055 | ||

| Mean segmental cap thickness of two adjacent slices with largest lipid core (mm) | 63 | Q1 (ref) | 0.631 (0.039) | — | 0.227 |

| 70 | Q2 | 0.664 (0.043) | 0.576 | ||

| 58 | Q3 | 0.584 (0.040) | 0.395 | ||

| 51 | Q4 | 0.706 (0.048) | 0.239 | ||

| Mean of the two minimum fibrous cap thickness in two adjacent slices (mm) | 63 | Q1 (ref) | 0.423 (0.031) | — | 0.270 |

| 70 | Q2 | 0.486 (0.035) | 0.180 | ||

| 58 | Q3 | 0.417 (0.038) | 0.905 | ||

| 51 | Q4 | 0.499 (0.042) | 0.151 | ||

| Total lipid-rich core volume on eight slices (mm3) | 62 | Q1 (ref) | 0.054 (0.008) | — | 0.137 |

| 70 | Q2 | 0.056 (0.009) | 0.888 | ||

| 58 | Q3 | 0.099 (0.023) | 0.031 | ||

| 51 | Q4 | 0.055 (0.011) | 0.974 | ||

| Maximum lipid-core area on eight slices (cm2) | 62 | Q1 (ref) | 0.096 (0.010) | — | 0.063 |

| 70 | Q2 | 0.098 (0.012) | 0.874 | ||

| 58 | Q3 | 0.155 (0.027) | 0.020 | ||

| 51 | Q4 | 0.107 (0.015) | 0.575 |

aCovariates for adjustment include age, gender, race, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, smoking status, body mass index, blood glucose, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, hypertensive medications, aspirin, clopidogrel , non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications, diabetic medications, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein.

Analyses stratified by race (Supplementary material online, Table S1a and b) showed more robust associations between RANTES and measures of carotid plaque burden (carotid wall thickness, carotid wall area, and carotid wall volumes) in Caucasians compared with African-Americans, although the number of African-American participants was much lower compared with their Caucasian counterparts.

Association between RANTES and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein

Mean high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels across increasing RANTES quartiles (Quartiles 1–4) were 3.75, 3.12, 3.15, and 3.82 mg/L, respectively (P = 0.07). In the fully adjusted models (Table 4), high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels showed positive albeit weak associations with increasing RANTES levels (β = 0.09, P = 0.01).

To further assess whether the positive relationship between high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and RANTES could be modulated by statins, we performed stratified analyses using statin (Supplementary material online, Table S2). RANTES levels were not positively associated with high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels in these stratified analyses, likely reflecting loss of power when performing these stratified analyses.

Discussion

The major findings of this study were that measures of atherosclerotic plaque burden (carotid arterial wall thickness and volumes) and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels were positively associated with RANTES. We also found that, although some measures of high-risk plaques (i.e. lipid-rich core volume) showed a positive association with RANTES in unadjusted models, other measures of high-risk plaques (thin fibrous cap) showed an inverse association (higher RANTES levels were associated with thicker fibrous caps). We also showed that plasma RANTES levels vary by race. In addition, we showed that statin use attenuates the association between RANTES and measures of plaque burden.

RANTES and measures of carotid atherosclerosis

Measures of plaque burden (carotid arterial wall thickness and volume) were positively associated with RANTES and coincided with our primary hypothesis. These data were also in line with prior data. It has been shown that RANTES plays a role in atherosclerosis and angiogenesis.3,19 Increasing levels of RANTES likely lead to a more robust cellular or a fibroproliferative response in the vessel wall as evidenced by an increase in total carotid wall volume and thickness in our study. Increasing RANTES levels were also associated with a positive remodelling response in the arterial wall as evidenced by an increase in vessel wall area with no decrease in lumen area.

Our findings on the association between RANTES and plaque morphology are intriguing. We hypothesized that greater RANTES levels would be associated with ‘high-risk' plaques (i.e. plaques with higher lipid-rich core volumes and thin fibrous caps). This was based on prior animal data which showed that RANTES receptor antagonism was associated with a decrease in T-cells, macrophage infiltration, and production of matrix metalloproteinase-9 levels and an increase in interstitial collagen and fibrous cap thickness of the atheromas.12 Our results showed that total lipid-rich core volume was positively associated with RANTES levels in unadjusted models. Similarly, although mean fibrous cap thickness was not associated with RANTES, mean minimum fibrous cap thickness was positively associated with RANTES levels. In summary, higher RANTES levels were associated with increasing lipid-rich core volumes (marker of high-risk plaques) and thicker fibrous caps (a finding associated with stable plaques rather than high-risk vulnerable plaques). Several explanations could account for these findings. First, measures such as wall thickness included the entire study group, whereas measures of plaque characteristics were limited to participants with a lipid core, leading to differences in statistical power. Secondly, the reliability estimates of the MRI variables were greatest for wall thickness and volume, less for lipid core, and least for fibrous cap measurements.18 Similarly, fibrous cap measurements would suffer the most from the resolution constraints of the MRI because these measurements were smaller compared with wall thickness or lipid-rich core volumes. Prior analysis18 which examined traditional risk factors and carotid atherosclerosis has also shown more robust associations with carotid thickness and volume measurements, but not necessarily carotid plaque composition.

Our results showed that although RANTES levels were associated with measures of increased plaque burden in the vessel wall, this response is considerably attenuated in patients using statins. This observation provides support to the immunomodulatory effects of statins. Apart from lowering low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, statins may provide vascular benefits in the arterial wall by inhibiting the inflammatory response associated with an increase in the levels of chemokines like RANTES. Other researchers have also shown that statins can either modulate RANTES levels or the RANTES receptor in the arterial wall,20–22 and these immunomodulatory effects of statins could at least partially explain vascular benefits associated with statin use.

RANTES and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein

We found that high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels were positively, albeit weakly, associated with plasma RANTES levels when both of these variables were evaluated in a continuous fashion, although the relationship was attenuated once this association was evaluated across RANTES quartiles, likely reflecting a loss of power when converting a continuous variable into categories. Recent data have shown that C-reactive protein can induce expression of RANTES in humans.23 We also show that plasma RANTES levels remained predictors of carotid atherosclerosis even after high-sensitivity C-reactive protein was added to the adjustment model.

In our analyses, RANTES levels were not significant predictors of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein when we performed stratified analyses using statin. This likely reflects the loss of statistical power while performing these stratified analyses.

Ethnic variation in plasma RANTES levels and their association with carotid atherosclerosis

Another important finding from our analysis is that levels of RANTES varied across race. RANTES levels were highest in Caucasian females, followed by Caucasian males, African-American females, and African-American males. These findings have important clinical and research implications. Our analyses stratified by race showed more consistent associations between RANTES and measures of carotid atherosclerosis in Caucasians compared with African-Americans. We believe that this is a reflection of the much smaller proportion of the African-Americans in the study (19%) compared with Caucasians, which likely lowered our statistical power to study associations between RANTES and measures of carotid atherosclerosis in African-Americans.

Though our analyses stratified by race are limited because of limited statistical power especially in African-Americans, it is possible that these racial differences in the level of RANTES may also explain varying results in prior clinical studies looking at plasma RANTES levels and outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease.13,14 These studies did not evaluate plasma RANTES levels across different ethnic and gender participants, and therefore, these differences could have accounted for varied findings.

Limitations

There are several limitations of the current study. First, the design was cross-sectional and measurements of plasma RANTES levels were performed at the same visit as carotid MRI. Therefore, our results only describe associations between carotid MRI variables and RANTES, and do not demonstrate causality. We measured RANTES levels in plasma, but it is possible that RANTES levels in tissues could be different from RANTES levels in plasma since RANTES are also secreted in the arterial wall by different cell types.3 Prior data showed a good correlation between plasma RANTES levels and tissue RANTES levels.24,25 However, there still remains a possibility that despite low levels in plasma, there could be high tissue expression of RANTES. This would be even more pathogenic since the primary action of RANTES occurs in the vessel wall and not in the circulation. Another limitation of the ARIC Carotid MRI substudy is that only the thicker carotid artery was imaged. This assumes that the morphology and composition of this plaque and its association with RANTES would be representative of all plaques within the carotid arteries for that individual and the entire vascular bed in general. Though there are data to support the notion that plaque characteristics are moderately correlated across vascular beds,26,27 the studies that looked at these associations were small; therefore, results may not be generalizable. Lastly, we studied the associations between carotid plaque characteristics and plasma RANTES levels in this study, but did not evaluate association between RANTES and cardiovascular events.

There were many strengths of this analysis. To our knowledge, this is the largest study to date evaluating the associations between RANTES and human arterial plaque burden and human arterial plaque characteristics. The study group was selected from the well-characterized population-based ARIC cohort. Both genders, as well as Caucasian and African-American races, were well represented, allowing for race- and gender-based analyses. Furthermore, MRI procedures were all standardized, and multiple quality-control measures were also employed.

There are future research and clinical implications from our findings that RANTES levels are associated with carotid plaque burden and possibly morphology of carotid plaques. Our results provide evidence that a strategy using carotid MRI could be efficiently employed to study how various other chemokines are associated with atherosclerosis burden as well as plaque morphology in humans before drug development is undertaken. Other emerging MRI measures like neovascularization could also be studied in the future to further enhance our understanding of the role played by chemokines in human atherosclerosis. In addition, RANTES receptor antagonism in the vascular wall may provide a therapeutic target to retard initiation or progression of atherosclerosis. It is interesting to note that an inhibitor of the RANTES receptor (maraviroc) has been shown to inhibit human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 binding to CD4 cells,28 and is currently approved for treatment of CCR5 tropic HIV-1 infection. Although antagonism of the RANTES receptor using recombinant RANTES (Met-RANTES) has been shown to limit the progression of atherosclerosis12 in mice models, this will have to be weighed against the deleterious effects of antagonizing RANTES receptor since RANTES are also involved in the early recruitment of macrophages and other systemic immune responses which might be important for the host's response to infections, especially those involving the T-cells and macrophages.29,30

We conclude that RANTES levels were positively associated with the extent of carotid atherosclerosis, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, as well as some measures of high-risk plaques in the ARIC Carotid MRI cohort. Statin use may modulate the relationship between RANTES and carotid atherosclerosis. We also conclude that plasma RANTES levels were dependent on race. This latter finding should be kept in mind while designing future studies to evaluate associations between RANTES and atherosclerosis.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal online.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [Contracts N01-HC-55015, N01-HC-55016, N01-HC-55018, N01-HC-55019, N01-HC-55020, N01-HC-55021, and N01-HC-55022 (The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study) and U01HL075572-01 (the ARIC Carotid MRI examination)]. S.S.V. is supported by a Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service (HSR&D) Career Development Award (grant number: CDA-09-028).

Conflict of interest: none declared

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions. The authors would also like to thank Ms Joanna A. Brooks for her editorial assistance.

References

- 1.Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1685–1695. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ross R. Atherosclerosis—an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:115–126. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von Hundelshausen P, Petersen F, Brandt E. Platelet-derived chemokines in vascular biology. Thromb Haemost. 2007;97:704–713. doi: 10.1160/th07-01-0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gear AR, Camerini D. Platelet chemokines and chemokine receptors: linking hemostasis, inflammation, and host defense. Microcirculation. 2003;10:335–350. doi: 10.1038/sj.mn.7800198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nieto M, Frade JM, Sancho D, Mellado M, Martinez AC, Sanchez-Madrid F. Polarization of chemokine receptors to the leading edge during lymphocyte chemotaxis. J Exp Med. 1997;186:153–158. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.1.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chuluyan HE, Schall TJ, Yoshimura T, Issekutz AC. IL-1 activation of endothelium supports VLA-4 (CD49d/CD29)-mediated monocyte transendothelial migration to C5a, MIP-1 alpha, RANTES, and PAF but inhibits migration to MCP-1: a regulatory role for endothelium-derived MCP-1. J Leukoc Biol. 1995;58:71–79. doi: 10.1002/jlb.58.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charo IF, Taubman MB. Chemokines in the pathogenesis of vascular disease. Circ Res. 2004;95:858–866. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000146672.10582.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baltus T, Weber KS, Johnson Z, Proudfoot AE, Weber C. Oligomerization of RANTES is required for CCR1-mediated arrest but not CCR5-mediated transmigration of leucocyte on inflamed endothelium. Blood. 2003;102:1985–1988. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schober A, Manka D, von Hundelshausen P, Huo Y, Hanrath P, Sarembock IJ, Ley K, Weber C. Deposition of platelet RANTES triggering monocyte recruitment requires P-selectin and is involved in neointima formation after arterial injury. Circulation. 2002;106:1523–1529. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000028590.02477.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bacon KB, Szabo MC, Yssel H, Bolen JB, Schall TJ. RANTES induces tyrosine kinase activity of stably complexed p125FAK and ZAP-70 in human T cells. J Exp Med. 1996;184:873–882. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Appay V, Dunbar PR, Cerundolo V, McMichael A, Czaplewski L, Rowland-Jones S. RANTES activates antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in a mitogen-like manner through cell surface aggregation. Int Immunol. 2000;12:1173–1182. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.8.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Veillard NR, Kwak B, Pelli G, Mulhaupt F, James RW, Proudfoot AE, Mach F. Antagonism of RANTES receptors reduces atherosclerotic plaque formation in mice. Circ Res. 2004;94:253–261. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000109793.17591.4E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nomura S, Uehata S, Saito S, Osumi K, Ozeki Y, Kimura Y. Enzyme immunoassay detection of platelet-derived microparticles and RANTES in acute coronary syndrome. Thromb Haemost. 2003;89:506–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cavusoglu E, Eng C, Chopra V, Clark LT, Pinsky DJ, Marmur JD. Low plasma RANTES levels are an independent predictor of cardiac mortality in patients referred for coronary angiography. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:929–935. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000258789.21585.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.von Hundelshausen P, Weber KS, Huo Y, Proudfoot AE, Nelson PJ, Ley K, Weber C. RANTES deposition by platelets triggers monocyte arrest on inflamed and atherosclerotic endothelium. Circulation. 2001;103:1772–1777. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.13.1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davies MJ, Richardson PD, Woolf N, Katz DR, Mann J. Risk of thrombosis in human atherosclerotic plaques: role of extracellular lipid, macrophage, and smooth muscle cell content. Br Heart J. 1993;69:377–381. doi: 10.1136/hrt.69.5.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galis ZS, Khatri JJ. Matrix metalloproteinases in vascular remodeling and atherogenesis: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Circ Res. 2002;90:251–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagenknect L, Wasserman B, Chambless L, Coresh J, Folsom A, Mosley T, Ballantyne C, Sharrett R, Boerwinkle E. Correlates of carotid plaque presence and composition as measured by magnetic resonance imaging: the Risk in Communities Study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2:314–322. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.108.823922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Westerweel PE, Rabelink TJ, Rookmaaker MB, Grone HJ, Verhaar MC. RANTES is required for ischaemia-induced angiogenesis, which may hamper RANTES-targeted anti-atherosclerotic therapy. Thromb Haemost. 2008;99:794–795. doi: 10.1160/TH07-10-0628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chana RS, Sidaway JE, Brunskill NJ. Statins but not thiazolidinediones attenuate albumin-mediated chemokine production by proximal tubular cells independently of endocytosis. Am J Nephrol. 2008;28:823–830. doi: 10.1159/000137682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nomura S, Shouzu A, Omoto S, Inami N, Tanaka A, Nanba M, Shouda Y, Takahashi N, Kimura Y, Iwasaka T. Correlation between adiponectin and reduction of cell adhesion molecules after pitavastatin treatment in hyperlipidemic patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Thromb Res. 2008;122:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Q, Wang D, Wang Y, Xu Q. Simvastatin down regulates mRNA expression of RANTES and CCR5 in posttransplant renal recipients with hyperlipidemia. Transplant Proc. 2006;38:2899–2904. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.08.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baer PC, Gauer S, Wegner B, Schubert R, Geiger H. C-reactive protein induced activation of MAP-K and RANTES in human renal distal tubular epithelial cells in vitro. Clin Nephrol. 2006;66:177–183. doi: 10.5414/cnp66177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Niwa Y, Akamatsu H, Niwa H, Sumi H, Ozaki Y, Abe A. Correlation of tissue and plasma RANTES levels with disease course in patients with breast or cervical cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:285–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niwa Y. Elevated RANTES levels in plasma or skin and decreased plasma IL-10 levels in subsets of patients with severe atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:125–126. doi: 10.1001/archderm.136.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fleiner M, Kummer M, Mirlacher M, Sauter G, Cathomas G, Krapf R, Biedermann BC. Arterial neovascularization and inflammation in vulnerable patients: early and late signs of symptomatic atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2004;110:2843–2850. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000146787.16297.E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naghavi M, Libby P, Falk E, Casscells SW, Litovsky S, Rumberger J, Badimon JJ, Stefanadis C, Moreno P, Pasterkamp G, Fayad Z, Stone PH, Waxman S, Raggi P, Madjid M, Zarrabi A, Burke A, Yuan C, Fitzgerald PJ, Siscovick DS, de Korte CL, Aikawa M, Airaksinen KE, Assmann G, Becker CR, Chesebro JH, Farb A, Galis ZS, Jackson C, Jang IK, Koenig W, Lodder RA, March K, Demirovic J, Navab M, Priori SG, Rekhter MD, Bahr R, Grundy SM, Mehran R, Colombo A, Boerwinkle E, Ballantyne C, Insull W, Jr., Schwartz RS, Vogel R, Serruys PW, Hansson GK, Faxon DP, Kaul S, Drexler H, Greenland P, Muller JE, Virmani R, Ridker PM, Zipes DP, Shah PK, Willerson JT. From vulnerable plaque to vulnerable patient: a call for new definitions and risk assessment strategies: Part II. Circulation. 2003;108:1772–1778. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000087481.55887.C9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gulick RM, Lalezari J, Goodrich J, Clumeck N, DeJesus E, Horban A, Nadler J, Clotet B, Karlsson A, Wohlfeiler M, Montana JB, McHale M, Sullivan J, Ridgway C, Felstead S, Dunne MW, van der Ryst E, Mayer H. Maraviroc for previously treated patients with R5 HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1429–1441. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0803152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vesosky B, Rottinghaus EK, Stromberg P, Turner J, Beamer G. CCL5 participates in early protection against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Leukoc Biol. 87:1153–1165. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1109742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vilela MC, Mansur DS, Lacerda-Queiroz N, Rodrigues DH, Lima GK, Arantes RM, Kroon EG, da Silva Campos MA, Teixeira MM, Teixeira AL. The chemokine CCL5 is essential for leucocyte recruitment in a model of severe Herpes simplex encephalitis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1153:256–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2008.03959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.