Abstract

Hypertension and left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy are both more common in blacks than in whites. The aim of the present study was to test the hypothesis that blood pressure (BP) has a differential effect on the LV geometry types in black versus white asymptomatic young adults. As a part of the Bogalusa Heart Study, echocardiography and cardiovascular risk factor measurements were performed in 780 white and 343 black subjects (aged 24 to 47 years). Four LV geometry types were identified as normal, concentric remodeling, eccentric, and concentric hypertrophy. Compared to the white subjects, the black subjects had a greater prevalence of eccentric (15.7% vs 9.1%, p < 0.001) and concentric (9.3% vs 4.1%, p < 0.001) hypertrophy. On multivariate logistic regression analyses, adjusting for age, gender, body mass index, lipids, and glucose, the black subjects showed a significantly stronger association of LV concentric hypertrophy with BP (systolic BP, odds ratio [OR] 3.74, p < 0.001; diastolic BP, OR 2.86, p < 0.001) than whites (systolic BP, OR 1.50, p = 0.037; and diastolic BP, OR 1.35, p = 0.167), with p values for the race difference of 0.007 for systolic BP and 0.026 for diastolic BP. LV eccentric hypertrophy showed similar trends for the race difference in the ORs; however, the association between eccentric hypertrophy and BP was not significant in the white subjects. With respect to LV concentric remodeling, its association with BP was not significant in either blacks or whites. In conclusion, elevated BP levels have a greater detrimental effect on LV hypertrophy patterns in the black versus white young adults. These findings suggest that blacks might be more susceptible than whites to BP-related adverse cardiac remodeling.

Hypertension is an important risk factor for left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy,1,2 a subclinical cardiovascular disease that represents one of the strongest independent predictors of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the general population.3–5 Although it is well known that hypertension and LV hypertrophy are both more common in blacks than in their white counterparts,6–8 data on whether high blood pressure (BP) levels are more closely associated with an increased LV mass in blacks than in whites have not been consistent.8–13 Also, information has been limited on how BP levels influence LV geometry and remodeling in black and white young adults. The objective of the present study was to examine the racial differences in the effect of BP on LV geometric patterns in black and white young adults enrolled in the Bogalusa Heart Study.

Methods

As a part of the Bogalusa Heart Study, a biracial (black–white) community-based investigation of the early nature history of cardiovascular disease, a total of 1,123 subjects (780 whites and 343 blacks, 42.2% men, age 24 to 47 years), who were residing in the community of Bogalusa, Louisiana, were examined for LV dimensions and cardiovascular risk factor variables in 2004 to 2008. All subjects in the present study gave informed consent for examination. The institutional review board of the Tulane University Medical Center approved the study protocols.

The BP levels were measured from the right arm of the subjects, with the subjects in a sitting position by 2 trained observers (3 replicates each). The systolic BP (SBP) and diastolic BP (DBP) were recorded at the first and fifth Korotkoff phases, respectively, using a mercury sphygmomanometer. The average of the 6 BP readings was used for analysis. For the 147 subjects who were taking medications for hypertension at the examination, the recorded BP values were adjusted by adding 10 mm Hg to the SBP and 5 mm Hg to the DBP, as determined by the average treatment effects.14,15 We tried to include these subjects because they represented a subgroup with the greatest BP.

The LV dimensions were assessed using 2-dimensional guided M-mode echocardiography, with 2.25- and 3.5-MHz transducers according to the American Society of Echocardiography recommendations.16 The parasternal long- and short-axis views were used to measure the LV end-diastolic and end-systolic measurements in duplicate, which were then averaged. The LV mass was calculated from a necropsy-validated formula according to thick wall prolate ellipsoidal geometry.17 To take the body size into account, the LV mass was indexed for body height (m2.7). The LV relative wall thickness was calculated as the septal wall thickness plus the posterior wall thickness divided by the LV end-diastolic diameter.18 The presence of LV hypertrophy was defined by a gender-specific cutoff of the LV mass index of >46.7g/m2.7 for women and >49.2g/m2.7 for men. The LV geometry was considered concentric when the relative wall thickness was >0.42.19 Four different patterns of LV geometry were defined: normal LV geometry, normal relative wall thickness with no LV hypertrophy; concentric remodeling, increased relative wall thickness but no LV hypertrophy; eccentric hypertrophy, normal relative wall thickness with LV hypertrophy; and concentric hypertrophy, increased relative wall thickness with LV hypertrophy.1,4,9,18–21

The cholesterol and triglyceride serum levels were assayed using enzymatic procedures on a Hitachi 902 automatic analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, Indiana). The glucose levels were measured as a part of a multiple chemistry profile (SMA20) using enzymatic procedures with a multichannel Olympus, Au-5000 analyzer (Olympus, Lake Success, New York). The laboratory was monitored for precision and accuracy of lipid measurements by the Lipid Standardization and Surveillance Program of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, Georgia).

All the statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). Analyses of covariance were performed using general linear models to test the differences in the study variables between the normal group and LV geometric remodeling groups. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to examine the associations of BP with concentric remodeling and different patterns of LV hypertrophy in separate models using normal geometry as a control. The race differences in odds ratios (ORs) for LV geometric patterns were tested by including the respective race–BP and race–covariate interaction terms in separate models. The SBP, DBP and covariates, except for gender, were standardized into Z scores with a mean of 0 and SD of 1 before logistic regression analyses to make the ORs comparable. The triglycerides and triglyceride/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio were log-transformed to improve the normality of the distribution in the general linear models and logistic regression models; however, the mean values in the original scales are listed in Table 1 for descriptive purposes.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study variables by race and patterns of left ventricular (LV) remodeling

| Variable | Blacks

|

Whites

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal (n = 230) | CR (n = 27) | EH (n = 54) | CH (n = 32) | Normal (n = 597) | EH (n = 71) | CH (n = 32) | CR (n = 80) | |

| Age (years) | 38 ± 5 | 39 ± 5 | 40 ± 4* | 39 ± 5 | 39 ± 4 | 39 ± 5 | 39 ± 5 | 40 ± 3 |

| Gender (n) | ||||||||

| Men | 87 | 13 | 23 | 8 | 241 | 49 | 44 | 9 |

| Women | 143 | 14 | 31 | 24† | 356 | 31* | 27 | 23† |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 29 ± 7 | 29 ± 6 | 37 ± 9* | 38 ± 10* | 28 ± 6 | 29 ± 5 | 36 ± 7* | 34 ± 6* |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 104 ± 67 | 86 ± 40 | 123 ± 111 | 115 ± 58 | 139 ± 105 | 157 ± 129 | 165 ± 122 | 169 ± 95 |

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dl) | 53 ± 15 | 54 ± 13 | 49 ± 12† | 50 ± 13 | 49 ± 13 | 44 ± 11 | 42 ± 12* | 44 ± 10* |

| Triglyceride/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio | 2.3 ± 2.2 | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 2.6 ± 2.1 | 2.6 ± 1.9 | 3.3 ± 3.2 | 4.2 ± 5.2 | 4.4 ± 3.8† | 4.0 ± 2.4 |

| Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dl) | 121 ± 35 | 109 ± 31 | 116 ± 46 | 122 ± 36 | 127 ± 33 | 127 ± 32 | 127 ± 31 | 135 ± 32 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 94 ± 37 | 85 ± 13 | 89 ± 20 | 107 ± 39* | 87 ± 18 | 90 ± 26 | 101 ± 31* | 100 ± 48* |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 119 ± 15 | 121 ± 14 | 134 ± 19* | 139 ± 19* | 113 ± 12 | 113 ± 11 | 121 ± 13* | 121 ± 15* |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 74 ± 11 | 74 ± 10 | 83 ± 12* | 86 ± 13* | 71 ± 9 | 71 ± 8 | 76 ± 8* | 76 ± 9* |

| Left ventricular mass index (g/m2.7) | 33 ± 7 | 36 ± 7† | 57 ± 8* | 59 ± 13* | 32 ± 8 | 36 ± 7* | 55 ± 8* | 55 ± 10* |

| Relative wall thickness | 0.32 ± 0.05 | 0.46 ± 0.03* | 0.35 ± 0.04* | 0.47 ± 0.05* | 0.32 ± 0.05 | 0.47 ± 0.05* | 0.36 ± 0.05* | 0.48 ± 0.06* |

Data are presented as mean ± SD for continuous variables.

Compared to normal, adjusting for gender and age,

p < 0.01;

p < 0.05.

CH = concentric hypertrophy; CR = concentric remodeling; EH = eccentric hypertrophy.

Results

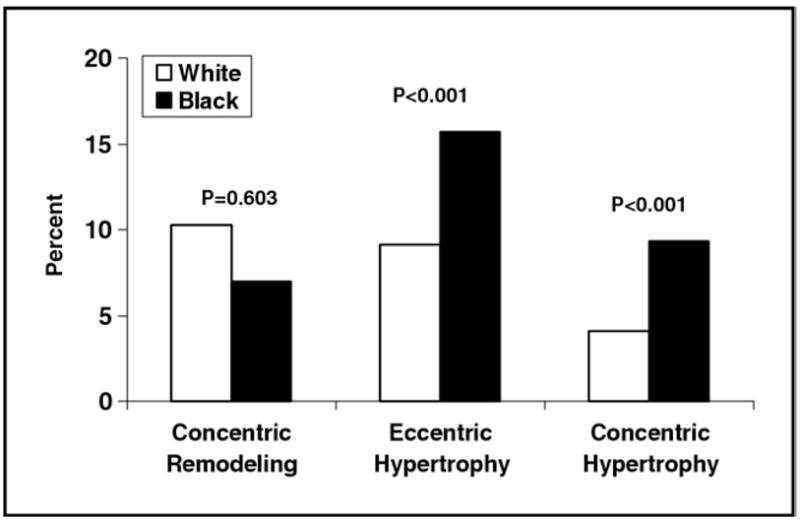

Figure 1 shows the prevalence of the LV geometric patterns by race. The black patients had a greater prevalence of eccentric hypertrophy (15.7% vs 9.1%, p < 0.001) and concentric hypertrophy (9.3% vs 4.1%, p < 0.001) than the white patients. Furthermore, the blacks had a greater prevalence of hypertension than the whites (33.2% vs 15.1%, p < 0.001). With respect to the overall average BP level by race groups, significant race differences in the BP mean levels were noted among those who were normotensive (SBP 111.1 mm Hg in whites and 115.1 mm Hg in blacks, p < 0.001; DBP 75.1 mm Hg in whites and 76.6 mm Hg in blacks, p < 0.001). Among those with hypertension, a significant race difference was noted in the SBP (135.7 mm Hg in whites and 143.8 mm Hg in blacks, p < 0.001) but not in DBP (94.3 mm Hg in whites and 95.5 mm Hg in blacks, p = 0.355).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of LV hypertrophy and geometric remodeling in blacks and whites: the Bogalusa Heart Study.

Table 1 lists the characteristics of the study variables by race and LV geometric patterns. Compared to the normal geometry group, those with eccentric and concentric hypertrophy showed significantly greater levels of body mass index (BMI), SBP, and DBP, adjusting for age and gender, in both blacks and whites. The mean BMI levels, lipid variables, glucose levels, and BP did not differ significantly between the normal geometry and concentric remodeling groups.

The association parameters (ORs) of BP with different LV geometric patterns derived from logistic regression models using the normal geometry as a control are listed in Table 2. The SBP and DBP levels (Z scores) were significantly associated with eccentric hypertrophy and concentric hypertrophy in blacks. In contrast, only SBP was associated with concentric hypertrophy among the whites. The BP levels were not associated with concentric remodeling for both blacks and whites. The BMI showed significant and consistent associations with eccentric hypertrophy and concentric hypertrophy in blacks and whites, but not with concentric remodeling. Female gender was associated with a lower risk of concentric remodeling; however, women were more likely to have concentric hypertrophy, especially in black women (OR 5.91 to 7.07, p < 0.01). With respect to race difference, the associations of SBP and DBP with eccentric and concentric hypertrophy were significantly stronger in the blacks than in the whites; the other study variables did not show race differences in the ORs.

Table 2.

Odds ratio (OR) for different left ventricular (LV) geometry patterns by race

| Variable | CR Versus Normal

|

EH Versus Normal

|

CH Versus Normal

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whites | Blacks | p Value* | Whites | Blacks | p Value* | Whites | Blacks | p Value* | |

| Model 1 | |||||||||

| Age | 1.05 | 1.28 | 0.501 | 1.25 | 1.63† | 0.398 | 1.59† | 1.13 | 0.356 |

| Women | 0.43** | 0.58 | 0.537 | 0.73 | 1.24 | 0.382 | 3.06† | 7.07‡ | 0.724 |

| Body mass index | 1.11 | 1.28 | 0.611 | 2.82‡ | 3.67‡ | 0.391 | 1.92‡ | 2.63‡ | 0.203 |

| Triglyceride/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio | 1.10 | 0.63 | 0.077 | 1.04 | 1.13 | 0.838 | 1.11 | 0.93 | 0.795 |

| Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol | 0.95 | 0.63 | 0.088 | 0.75† | 0.58‡ | 0.403 | 0.93 | 0.82 | 0.817 |

| Glucose | 1.12 | 0.77 | 0.214 | 1.21 | 0.48 | 0.077 | 1.31† | 1.20 | 0.670 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 0.83 | 1.02 | 0.700 | 0.95 | 1.82‡ | 0.016 | 1.50† | 3.74‡ | 0.007 |

| Model 2 | |||||||||

| Age | 1.04 | 1.32 | 0.484 | 1.27 | 1.66† | 0.402 | 1.65† | 1.16 | 0.267 |

| Women | 0.42‡ | 0.57 | 0.526 | 0.73 | 0.81 | 0.404 | 3.09† | 5.91‡ | 0.713 |

| Body mass index | 1.08 | 1.35 | 0.607 | 2.95‡ | 3.36‡ | 0.447 | 2.06‡ | 2.49‡ | 0.353 |

| Triglyceride/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio | 1.10 | 0.65 | 0.076 | 1.05 | 1.20 | 0.889 | 1.10 | 0.96 | 0.755 |

| Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol | 0.95 | 0.62 | 0.091 | 0.76 | 0.59‡ | 0.344 | 0.94 | 0.76 | 0.627 |

| Glucose | 1.11 | 0.77 | 0.211 | 1.22 | 0.47 | 0.065 | 1.33† | 1.16 | 0.492 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 0.90 | 0.83 | 0.601 | 0.84 | 1.62* | 0.017 | 1.35 | 2.86‡ | 0.026 |

Continuous variables were standardized into Z scores, with mean = 0 and SD = 1.

p Values for race difference in ORs;

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01 for significance of OR.

Abbreviations as in Table 1.

The ORs with BP levels and hypertension status for LV geometric patterns, including the same covariates as those in Table 2, but using a different cohort (147 subjects receiving treatment excluded) in model 1 or a different predictor (hypertension status) in model 2 are listed in Table 3. In model 1, compared to the corresponding results listed in Table 2, the race difference in ORs with SBP and DBP levels (Z scores) did not change much for eccentric hypertrophy; however, the magnitude of the race difference in ORs was considerably increased for concentric hypertrophy. Using hypertension (yes vs no) as a predictor variable in model 2, a similar pattern in the race difference in the ORs for concentric hypertrophy was seen.

Table 3.

Odds ratios (ORs) for different left ventricular (LV) geometry patterns by race

| Variable | CR Versus Normal

|

EH Versus Normal

|

CH Versus Normal

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whites | Blacks | p Value* | Whites | Blacks | p Value* | Whites | Blacks | p Value* | |

| Model 1 | |||||||||

| Systolic blood pressure | 0.81 | 1.06 | 0.685 | 0.70 | 1.70† | 0.008 | 1.23 | 4.69‡ | 0.003 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 0.87 | 0.79 | 0.542 | 0.74 | 1.75† | 0.004 | 1.03 | 4.45‡ | 0.004 |

| Model 2 | |||||||||

| Hypertension | 1.01 | 1.28 | 0.864 | 1.68 | 2.60† | 0.127 | 2.14* | 6.21‡ | 0.014 |

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure were standardized into Z-scores, with mean = 0 and SD = 1.

Same covariates as those listed in Table 2 were included in models 1 and 2.

Hypertension was coded as 0 = no or 1 = yes.

p Values for race difference in ORs;

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01 for significance of OR.

Model 1, subjects receiving treatment (n = 174) were excluded; model 2, all subjects were included

Abbreviations as in Table 1.

Discussion

The evidence that blacks had a greater prevalence of hypertension and LV hypertrophy than whites is almost indisputable; however, the data on racial differences in the magnitude of the BP–LV mass association have been inconsistent.8–13 In the present biracial community-based study of asymptomatic young adults, the main finding was that the BP levels were more strongly associated with LV eccentric and concentric hypertrophy in the blacks than in the whites. In addition, the well-documented black–white difference in BP levels and the prevalence of hypertension was also noted in the present study cohort. These observations suggest that in addition to the black–white difference in the prevalence of hypertension, black patients with hypertension are more susceptible to LV hypertrophy than their white counterparts.

Comparing the ORs for LV hypertrophy between the blacks and whites derived from the logistic regression interaction models in the present study provided appropriate and straightforward parameters to measure the racial difference in the effect of BP on LV hypertrophy. The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study,9 which had a similar age range to our cohort, reported Pearson correlation coefficients between the BP and LV mass in a longitudinal analysis and a BP trend with tertile groups of LV mass in a cross-sectional analysis. The black subjects had greater association parameters than did the whites, but the significance of the racial difference was not tested in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study. Another approach has been to use the adjustment of BP levels to examine its effect on the racial differences in the LV mass. Studies using the adjustment method found that after multivariate adjustment for BP, anthropometric and lipid variables, and other covariates, the LV mass still remained greater in the blacks than in the whites.8,10 These findings suggest that the greater prevalence of LV hypertrophy cannot be fully accounted for by the greater prevalence of hypertension in the black population. In contrast, other studies have reported inconsistent or conflicting results regarding the BP–LV mass association in blacks and whites.12,13,22 Among a number of influencing factors, the sample size and selection, age range, and the definition of LV hypertrophy are possibly responsible for the discrepancies of the results in this regard. Furthermore, on the univariate analyses (Table 1), in the present study, those with eccentric and concentric hypertrophy showed significantly greater levels of BMI, SBP, and DBP, adjusting for age and gender, in both blacks and whites compared to the normal geometry group. However, the BP–eccentric hypertrophy associations became nonsignificant in whites on multivariate analyses (Table 2), suggesting the complex interactions between BP and other cardiovascular risk factors, in particular, the interaction between BP and BMI.

Echocardiography has allowed identification of different forms of LV geometric remodeling, including eccentric or concentric hypertrophy and disproportionate septal thickness. Although the significance of the different forms, however, has not yet been well defined, concentric hypertrophy has been considered to carry the greatest risk of cardiovascular events4,5 and has been the predominant form in middle-age and elderly patients with hypertension.23 In the young adult cohort from the general population in the present study, the prevalence of concentric hypertrophy was 9.3% in blacks and 4.1% in whites. In the Framingham Offspring study, which consisted largely of whites with a mean age of 44 years, the prevalence of concentric hypertrophy was 3.4% in men and 1.8% in women.23 In a study of patients with hypertension and a mean age of 46 years in blacks and 47 years in whites, the blacks had twice the prevalence of LV hypertrophy (including both eccentric and concentric hypertrophy) in the whites (41% vs 19%).24 The black–white difference in the prevalence of concentric hypertrophy was noted even in children with a mean age of 14.7 years (13.1% in black children and 3.8% in white children).25 Obviously, different age groups, BP levels, and cutoff points of relative wall thickness and LV mass have been largely responsible for the differences in the prevalence rates reported by different studies.

Obesity is an established risk factor of LV hypertrophy.26–28 Obesity and hypertension occurring together place a dual burden on the left ventricle and are associated with metabolic abnormalities.27 The association between obesity and LV hypertrophy is reported to originate in childhood.29 In our previous longitudinal study, childhood obesity was found to predict the adulthood LV mass in a cohort from the same population.30 In some early reports, obesity appears to be a more consistent and stronger determinant of LV hypertrophy than BP levels or hypertension.8–10,27 In the present study, the BMI showed a more consistent association with LV hypertrophy and stronger association with eccentric hypertrophy than BP in both blacks and whites by comparing the ORs derived using standardized variables. However, the effect of BMI on LV hypertrophy did not differ significantly between the blacks and whites, suggesting that despite the greater effect of BMI, the BP might contribute more than obesity to the black–white difference in the prevalence of LV hypertrophy. Importantly, as mentioned, the adjustment for BMI and other cardiovascular risk variables resulted in a nonsignificant association between eccentric hypertrophy and BP in whites, suggesting a potential interaction between the BP and BMI.

Gender is a strong determinant of both body size and LV mass. Therefore, we used gender-specific cutoffs to identify the LV geometric patterns in the present study. In the multivariate analyses (Table 2), female gender was associated with a lower risk of concentric remodeling; however, women were more likely to have concentric hypertrophy, especially for black women. Among the white subjects in the Framingham study, the prevalence of concentric hypertrophy was 10.6% in the men and 15.9% in the women in the original cohort (mean age 68 years) and 3.4% in men and 1.8% in women for the offspring-spouse cohort (mean age 44 years).23 Data were not available for comparison in blacks regarding the prevalence of concentric hypertrophy by gender. The observation of the greater risk of concentric hypertrophy in women in the present study, particularly in black women, needs to be studied further.

In the present community-based epidemiologic study, a major limitation was the adjustment of adding 10 mm Hg and 5 mm Hg to the SBP and DBP value, respectively, for subjects taking antihypertensive medications. Although this approach has been commonly used according to the average treatment effects,14,15 it is an approximate estimation and might have led to a bias in the data analyses to some extent, because information on the drugs taken for the treatment was not available. Therefore, we also analyzed the data by excluding these subjects. The results indicated that the bias might lead to an underestimation of the race difference in the association.

The present study have provided evidence supporting the hypothesis that the greater prevalence of LV hypertrophy in blacks than in whites has resulted from both a greater prevalence of hypertension and a stronger influence of BP on LV hypertrophy in blacks. In contrast, the influence of obesity on the BP–LV hypertrophy relation was more evident in the whites than in the blacks. These findings reflect the black–white divergence in the pathogenesis of LV hypertrophy and the potential role in the development of cardiovascular disease. A better understanding of the disparities of the pathophysiologic basis of LV hypertrophy by race and ethnicity might help clinicians and public health professionals develop culturally sensitive interventions, prevention programs, and services specifically targeted toward risk burdens in different populations.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants HD-061437 and HD-062783 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, grant 0855082E from the American Heart Association, and grant AG-16592 from the National Institute on Aging, Bethesda, Maryland.

References

- 1.Frohlich ED, Apstein C, Chobanian AV, Devereux RB, Dustan HP, Dzau V, Fauad-Tarazi F, Horan MJ, Marcus M, Massie B, Pfeffer MA, Re RN, Roccella EJ, Savage D, Shub C. The heart in hypertension. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:998–1008. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199210013271406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diamond JA, Phillips RA. Hypertensive heart disease. Hypertens Res. 2005;28:191–202. doi: 10.1291/hypres.28.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy D, Garrison RJ, Savage DD, Kannel WB, Castelli WP. Prognostic implications of echocardiographically determined left ventricular mass in the Framingham Heart Study. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1561–1566. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199005313222203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verdecchia P, Angeli F, Achilli P, Castellani C, Broccatelli A, Gattobigio R, Cavallini C. Echocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertension: marker for future events or mediator of events? Curr Opin Cardiol. 2007;22:329–334. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e3280ebb413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koren MJ, Devereux RB, Casale PN, Savage DD, Laragh JH. Relation of left ventricular mass and geometry to morbidity and mortality in uncomplicated essential hypertension. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:345–352. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-5-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burt VL, Whelton P, Roccella EJ, Brown C, Cutler JA, Higgins M, Horan MJ, Labarthe D. Prevalence of hypertension in the US adult population: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1991. Hypertension. 1995;25:305–313. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.25.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drazner MH, Dries DL, Peshock RM, Cooper RS, Klassen C, Kazi F, Willett D, Victor RG. Left ventricular hypertrophy is more prevalent in blacks than whites in the general population: the Dallas Heart Study. Hypertension. 2005;46:124–129. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000169972.96201.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kizer JR, Arnett DK, Bella JN, Paranicas M, Rao DC, Province MA, Oberman A, Kitzman DW, Hopkins PN, Liu JE, Devereux RB. Differences in left ventricular structure between black and white hypertensive adults: the Hypertension Genetic Epidemiology Network study. Hypertension. 2004;43:1182–1188. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000128738.94190.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lorber R, Gidding SS, Daviglus ML, Colangelo LA, Liu K, Gardin JM. Influence of systolic blood pressure and body mass index on left ventricular structure in healthy African-American and white young adults: the CARDIA study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:955–960. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gardin JM, Wagenknecht LE, Anton-Culver H, Flack J, Gidding S, Kurosaki T, Wong ND, Manolio TA. Relationship of cardiovascular risk factors to echocardiographic left ventricular mass in healthy young black and white adult men and women: the CARDIA study. Circulation. 1995;92:380–387. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.3.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunn FG, Oigman W, Sugaard-Riise MFH, Ventura H, Reisin E, Frohlich ED. Racial differences in cardiac adaptation to essential hypertension determined by echocardiographic indexes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1983;5:1348–1351. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(83)80150-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayet J, Chapman N, Li CKC, Shahi M, Poulter NR, Sever PS, Foale RA, Thom SA. Ethnic differences in the hypertensive heart and 24-hour blood pressure profile. Hypertension. 1998;31:1190–1194. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.5.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammond IW, Alderman MH, Devereux RB, Lutas EM, Laragh JH. Contrast in cardiac anatomy and function between black and white patients with hypertension. J Natl Med Assoc. 1984;76:247–255. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cui J, Hopper JL, Harrap SB. Genes and family environment explain correlations between blood pressure and body mass index. Hypertension. 2002;40:7–12. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000022693.11752.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neaton JD, Grimm RH, Jr, Prineas RJ, Stamler J, Grandits GA, Elmer PJ, Cutler JA, Flack JM, Schoenberger JA, McDonald R. Treatment of mild hypertension study: final results—Treatment of Mild Hypertension Study Research group. JAMA. 1993;270:713–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sahn DJ, DeMaria A, Kisslo J, Weyman A. Recommendations regarding quantitation in M-mode echocardiography: results of a survey of echocardiographic measurements. Circulation. 1978;58:1072–1083. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.58.6.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Devereux RB, Alonso DR, Lutas EM, Gottlieb GJ, Campo E, Sachs I, Reichek N. Echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular hypertrophy: comparison to necropsy findings. Am J Cardiol. 1986;57:450–458. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(86)90771-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foppa M, Duncan BB, Rohde L. Echocardiography-based left ventricular mass estimation: how should we define hypertrophy? Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2005;3:17–29. doi: 10.1186/1476-7120-3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Simone G, Kitzman DW, Chinali M, Oberman A, Hopkins PN, Rao DC, Arnett DK, Devereux RB. Left ventricular concentric geometry is associated with impaired relaxation in hypertension: the HyperGEN study. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:1039–1045. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ganau A, Devereux RB, Roman MJ, de Simone G, Pickering TG, Saba PS, Vargiu P, Simongini I, Laragh JH. Patterns of left ventricular hypertrophy and geometric remodeling in essential hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;19:1550–1558. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90617-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toprak A, Reddy J, Chen W, Srinivasan S, Berenson G. Relation of pulse pressure and arterial stiffness to concentric left ventricular hypertrophy in young men (from the Bogalusa Heart Study) Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:978–984. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skelton TN, Andrew ME, Arnett DK, Burchfiel CM, Garrison RJ, Samdarshi TE, Taylor HA, Hutchinson RG. Echocardiographic left ventricular mass in African-Americans: the Jackson cohort of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Echocardiography. 2003;20:111–120. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8175.2003.03000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Savage DD, Garrison RJ, Kannel WB, Levy D, Anderson SJ, Stokes J, 3rd, Feinleib M, Castelli WP. The spectrum of left ventricular hypertrophy in a general population sample: the Framingham Study. Circulation. 1987;75:I-26-I–I-2633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koren MJ, Mensah GA, Blake J, Laragh JH, Devereux RB. Comparison of left ventricular mass and geometry in black and white patients with essential hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 1993;6:815–823. doi: 10.1093/ajh/6.10.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daniels SR, Loggie JMH, Khoury P, Kimball TR. Left ventricular geometry and severe left ventricular hypertrophy in children and adolescents with essential hypertension. Circulation. 1998;97:1907–1911. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.19.1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chirinos JA, Segers P, De Buyzere ML, Kronmal RA, Raja MW, De Bacquer D, Claessens T, Gillebert TC, St John-Sutton M, Rietzschel ER. Left ventricular mass: allometric scaling, normative values, effect of obesity, and prognostic performance. Hypertension. 2010;56:91–98. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.150250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lavie CJ, Ventura HO, Messerli FH. Left ventricular hypertrophy: its relationship to obesity and hypertension. Postgrad Med. 1992;91:135–138. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1992.11701350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuch B, Hense HW, Gneiting B, Döring A, Muscholl M, Bröckel U, Schunkert H. Body composition and prevalence of left ventricular hypertrophy. Circulation. 2000;102:405–410. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.4.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dhuper S, Abdullah RA, Weichbrod L, Mahdi E, Cohen HW. Association of obesity and hypertension with left ventricular geometry and function in children and adolescents. Obesity. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.134. Epub 2010 Jun 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li X, Li S, Ulusoy E, Chen W, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. Childhood adiposity as a predictor of cardiac mass in adulthood: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Circulation. 2004;110:3488–3492. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000149713.48317.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]