Abstract

The prevalence of hypertension is higher among African-Americans than whites. However, inconsistent findings have been reported on the incidence of hypertension among middle-aged and older African-Americans and whites and limited data are available on the incidence of hypertension among Hispanics and Asians in the US. Therefore, this study investigated the age-specific incidence of hypertension by ethnicity for 3,146 participants from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Participants, age 45–84 years at baseline, were followed for a median of 4.8 years for incident hypertension, defined as systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg, or the initiation of antihypertensive medications. The crude incidence rate of hypertension, per 1,000 person-years, was 56.8 for whites, 84.9 for African-Americans, 65.7 for Hispanics, and 52.2 for Chinese. After adjustment for age, gender, and study site, the incidence rate ratio (IRR) for hypertension was increased for African-Americans age 45–54 (IRR=2.05, 95% CI=1.47, 2.85), 55–64 (IRR=1.63, 95% CI=1.20, 2.23), and 65–74 years (IRR=1.67, 95% CI=1.21, 2.30) compared with whites, but not for those 75–84 years of age (IRR=0.97, 95% CI=0.56, 1.66). Additional adjustment for health characteristics attenuated these associations. Hispanic participants also had a higher incidence of hypertension compared with whites; however, hypertension incidence did not differ for Chinese and white participants. In summary, hypertension incidence was higher for African-Americans compared with whites between 45 and 74 years of age but not after age 75 years. Public health prevention programs tailored to middle-age and older adults are needed to eliminate ethnic disparities in incident hypertension.

Keywords: hypertension, race/ethnicity, epidemiology, incidence

INTRODUCTION

Hypertension affects approximately one-third of adults in the United States and is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality.1 The prevalence of hypertension increases with age and is higher among African-Americans compared with whites and Hispanics at all ages.2, 3 Previous data suggests African-Americans have higher blood pressure levels than whites beginning in childhood.4, 5 Additionally, studies of young adults have consistently found a higher incidence of hypertension among African-Americans compared with whites.6, 7 However, inconsistent data have been reported on incident hypertension for African-Americans compared with whites in middle-age and older adulthood. In the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey I follow-up study, the incidence of hypertension over 9.5 years of follow-up was similar among African-American and white participants age 55 years and older at baseline.7 A study of adults ages 30–54 years at baseline also reported a similar incidence of hypertension among African-Americans and whites over a 7 year follow-up period.8 Conversely, in a study of adults ages 45–64 years at baseline, African-Americans had a higher incidence of hypertension compared with whites over 3 years of follow-up.9

Data investigating hypertension among other ethnicities are limited, with previous studies primarily assessing prevalent hypertension. Several studies have reported a similar prevalence of hypertension among Hispanics and whites,2, 10, 11 while others have reported a lower hypertension prevalence for Hispanics compared with whites.12, 13 Also, Asians have been reported to have a similar prevalence of hypertension as whites.14 However, in some studies, a lower prevalence of hypertension has been reported for Chinese and Japanese ethnic groups compared with whites.15, 16 Little information is available for incident hypertension among Hispanics and Asians in the US. In the San Antonio Heart Study, the overall incidence of hypertension was similar among Mexican-Americans and non-Hispanic whites over 8 years of follow-up.17 However, in analyses stratified by age, the incidence of hypertension in the oldest age group, 55–64 years, was higher among Mexican-Americans compared with non-Hispanic whites for both men and women.17

Given the limited published data, it remains unclear whether ethnic disparities in the incidence of hypertension are present among middle aged and older adults in the US. Therefore, we analyzed data on the incidence of hypertension among African-American, Chinese, Hispanic, and white participants from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), a population-based cohort study of men and women ages 45 to 84 years at baseline from six US communities.

METHODS

Study Design and Population

MESA is a prospective, population-based cohort study designed to investigate the characteristics of subclinical atherosclerosis and the risk factors for progression of subclinical disease to clinical cardiovascular disease among multiple ethnic groups. The study recruited 6,814 men and women, ages 45–84 years at baseline without a history of clinical cardiovascular disease, from six US communities: Baltimore, Maryland; Chicago, Illinois; Forsyth County, North Carolina; Los Angeles County, California; New York, New York; and St. Paul, Minnesota. Participants completed a baseline examination in 2000–2002 and subsequent examinations in 2002–2004 (Examination 2), 2004–2005 (Examination 3), and 2005–2007 (Examination 4). Between examinations, participants were contacted to ascertain the occurrence of any medical events or changes in health status. The study design and objectives have been previously published.18 The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each participating site and participants provided written informed consent.

For the current analysis, participants with prevalent hypertension at baseline (n=3,507), defined as systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 90 mmHg, current antihypertensive medication use, or a self-reported prior diagnosis of hypertension, were excluded. Also, participants without blood pressure measurements at baseline (n=1) and those who did not attend a MESA follow-up examination (n=160) were excluded resulting in a sample size of 3,146 participants for these analyses.

Ascertainment of Ethnicity

Participants self-reported ethnicity as white, African-American, Asian (primarily of Chinese descent), or Hispanic based on questions adapted from the 2000 US Census. Approximately 38% of the recruited participants were white, 28% African-American, 12% Chinese, and 22% Hispanic. White participants were recruited from all study sites. African-American participants were recruited from all study sites except St. Paul, Minnesota. Chinese participants were recruited from Chicago, Illinois and Los Angeles, California. Hispanic participants were recruited from St. Paul, Minnesota; New York, New York; and Los Angeles, California.

Ascertainment of Incident Hypertension

SBP and DBP were measured at each MESA examination following standardized protocols.19 Briefly, after resting for 5 minutes in the seated position, blood pressure was measured three times at two-minute intervals using an appropriate sized cuff and an automated oscillometric device (Dinamap Monitor Pro 100, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI), with the average of the second and third measurements used to determine SBP and DBP. Additionally, MESA participants were asked to bring all medication to each examination where drug names and doses were abstracted from medication bottles.

Incident hypertension was defined as the first study visit, subsequent to baseline, at which the participant had SBP ≥ 140 mmHg and/or DBP ≥ 90 mmHg and/or had initiated treatment with antihypertensive medications.

Ascertainment of Covariates

Information on socio-demographic factors (age, gender, and education), and lifestyle factors (alcohol consumption and smoking status) was collected at the baseline examination using standardized questionnaires. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Depressive symptoms were assessed using self-reported responses to the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale,20 with higher scores indicative of more depressive symptoms. Dietary information was obtained from a self-administered 120-item block food frequency questionnaire21 that was modified to include ethnic and geographic specific foods and used to obtain sodium/potassium (Na/K) intake adjusted for total energy intake. Participants fasted for 12 hours prior to each MESA examination for the collection of fasting blood samples. Diabetes mellitus was defined as fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dL or use of hypoglycemic medication. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation.22 Parental history of hypertension at examination 2 was self-reported and used in these analyses because it was not collected at baseline.

Statistical Analyses

Baseline characteristics of MESA participants were calculated overall, and by ethnicity, using means or frequencies as appropriate. The crude incidence rates of hypertension were calculated among whites, African-Americans, Chinese, and Hispanics, separately. Follow-up time for participants who developed hypertension was calculated as the number of years between their baseline examination and the first examination when incident hypertension criteria were fulfilled. Follow-up time for participants who did not develop hypertension was calculated as the number of years between their baseline examination and examination 4 or the last study examination completed for those who did not attend examination 4 (i.e., examination 2 for 82 participants and examination 3 for 107 participants). Crude incidence rates were also calculated for each ethnic group stratified by baseline age (45–54, 55–64, 65–74, and 75–84 years).

Poisson regression models were used to calculate incidence rate ratios (IRR) for hypertension for African-Americans, Chinese, and Hispanics, separately, versus whites. An initial model included adjustment for age (continuous), gender, and MESA study site. The next model included additional adjustment for education (less than high school, high school graduate, greater than high school), BMI (continuous), smoking status (current, former, never), alcohol consumption (current, former, never), CES-D score, quintile of Na/K ratio, diabetes, eGFR < 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, and parental history of hypertension (both parents, one parent, or none). The final model included additional adjustment for baseline SBP and DBP modeled as continuous variables. In the multivariable models, 311 participants were excluded for missing covariate values, primarily Na/K information (n=256). Effect modification by age, gender, and education were evaluated, with age being the only statistically significant effect modifier using an a priori cut-point of p < 0.10. Therefore, age-stratified (45–54, 55–64, 65–74, and 75–84 years) IRRs were calculated adjusting for the variables used in the previous models. Poisson regression models including linear, quadratic, and cubic age terms and gender were used to obtain age-specific IRRs for hypertension comparing African-Americans, Chinese, and Hispanic participants, separately, with whites. Also, the practical incidence estimators macro approach was used to obtain the lifetime risk (cumulative incidence through age 85 years) of hypertension, by ethnicity, adjusting for the competing risk of death.23 All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Participant socio-demographic and health characteristics at baseline are presented, overall and by ethnicity, in Table 1. The mean age of participants was 58.6 years, 52.1% of the participants were women, and the ethnicity of participants included in these analyses was 43% white, 20% African-American, 14% Chinese, and 23% Hispanic. A higher proportion of Chinese and Hispanic participants reported less than a high school education. African-Americans had the highest proportion of current smokers (22.2%) while white participants had the highest proportion of current alcohol drinkers (75.3%). White participants had the lowest prevalence of diabetes mellitus (2.6%) and the highest prevalence of an eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73m2 (7.5%). A parental history of hypertension was highest for African-Americans (49.5%), followed by 43.2% of Chinese participants, 38.8% of white participants, and 33.7% of Hispanic participants. Also, African-American participants had the highest mean BMI, SBP and DBP at baseline.

Table 1.

Baseline participant characteristics, overall and by ethnicity, the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (2000–2002)

| Characteristic | Total (n = 3146) | White (n = 1358) | African-American (n = 630) | Chinese (n = 424) | Hispanic (n = 734) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD), years | 58.6 (9.7) | 59.6 (9.8) | 57.9 (9.7) | 58.8 (9.5) | 57.5 (9.6) |

| Women, n (%) | 1638 (52.1) | 720 (53.0) | 338 (53.7) | 218 (51.4) | 362 (49.3) |

| < High school education, n (%) | 453 (14.4) | 40 (3.0) | 49 (7.8) | 89 (21.0) | 275 (37.5) |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 465 (14.8) | 175 (12.9) | 140 (22.2) | 25 (5.9) | 125 (17.0) |

| Current alcohol consumption, n (%) | 1903 (60.5) | 1022 (75.3) | 357 (56.7) | 140 (33.0) | 384 (52.3) |

| Mean BMI (SD), kg/m2 | 27.3 (5.1) | 26.7 (4.6) | 29.1 (5.7) | 23.5 (3.1) | 28.9 (5.0) |

| Mean CES-D score (SD) | 7.5 (7.7) | 6.8 (7.0) | 7.0 (7.1) | 6.4 (6.7) | 9.8 (9.4) |

| Mean Na/K ratio (SD) | 0.85 (0.29) | 0.80 (0.27) | 0.91 (0.34) | 0.92 (0.28) | 0.85 (0.28) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 192 (6.1) | 35 (2.6) | 52 (8.3) | 37 (8.7) | 68 (9.3) |

| Estimated GFR < 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, n (%) | 155 (4.9) | 102 (7.5) | 14 (2.2) | 16 (3.8) | 23 (3.1) |

| Parental history of hypertension, n (%) | 1269 (40.3) | 527 (38.8) | 312 (49.5) | 183 (43.2) | 247 (33.7) |

| Mean systolic blood pressure (SD), mm Hg | 114.2 (12.9) | 113.4 (13.0) | 117.0 (12.0) | 112.3 (13.4) | 114.3 (12.8) |

| Mean diastolic blood pressure (SD), mm Hg | 68.6 (8.6) | 67.6 (8.8) | 71.0 (7.7) | 68.5 (8.8) | 68.6 (8.7) |

BMI = body mass index; CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; Na/K = sodium/potassium; GFR = glomerular filtration rate; SD = standard deviation

Over a median follow-up of 4.8 years (maximum = 6.7 years), 910 participants developed incident hypertension. Among participants identified with incident hypertension, 444 (48.8%) met SBP and/or DBP criteria alone (i.e., SBP ≥ 140 mmHg or DBP ≥ 90 mmHg but not taking antihypertensive medications); 416 (45.7%) met antihypertensive medication criterion alone (i.e., SBP < 140 mmHg and DBP < 90 mmHg but taking antihypertensive medications); and 50 (5.5%) met both SBP and/or DBP criteria and antihypertensive medication criteria (i.e., SBP ≥ 140 mmHg or DBP ≥ 90 mmHg and antihypertensive medication use). The crude incidence rates and adjusted IRRs are presented by ethnicity in Table 2. African-Americans had the highest incidence rate (84.9 per 1000 person-years) and Chinese participants had the lowest incidence rate (52.2 per 1000 person-years). Compared with white participants, the age, gender, and MESA study site adjusted IRR for hypertension was increased for African-American (IRR = 1.65; 95% CI: 1.39 – 1.96) and Hispanic (IRR = 1.29; 95% CI: 1.06 – 1.57) but not Chinese participants (IRR = 1.05; 95% CI: 0.81 – 1.35). Additional adjustment for health characteristics and baseline SBP and DBP attenuated these associations, and the IRR remained statistically significant only for African-Americans compared with whites (IRR = 1.23; 95% CI: 1.01 – 1.49).

Table 2.

Incidence rates and adjusted incidence rate ratios (95% CI) for hypertension

| Ethnicity | Crude incidence rate per 1000 person-years | Adjusted Incidence Rate Ratio (95% CI)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||

| White | 56.8 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| African-American | 84.9 | 1.65 (1.39, 1.96) | 1.39 (1.15, 1.69) | 1.23 (1.01, 1.49) |

| Chinese | 52.2 | 1.05 (0.81, 1.35) | 1.12 (0.85, 1.49) | 1.00 (0.76, 1.33) |

| Hispanic | 65.7 | 1.29 (1.06, 1.57) | 1.04 (0.83, 1.31) | 0.98 (0.78, 1.23) |

Model 1 adjusted for age, gender, and MESA study site

Model 2 adjusted for variables in Model 1 plus education, body mass index, smoking status, alcohol consumption, depressive symptoms, Na/K ratio, diabetes, estimated glomerular filtration rate<60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, and parental history of hypertension

Model 3 adjusted for variables in Models 1 and 2 plus baseline systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure

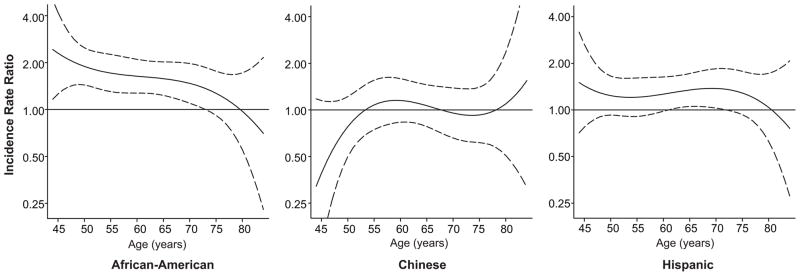

The gender-adjusted age-specific IRRs for hypertension are presented in Figure 1 for each ethnicity, separately, with white participants as the reference group. As age increased, the IRR decreased for African-Americans. No statistically significant association with hypertension incidence was noted at any age for Chinese participants compared with white participants. For Hispanic participants, the IRR was above one until age 70 years at which point it began to decrease.

Figure 1.

Age-specific incidence rate ratios for hypertension for African-American, Chinese, and Hispanic participants compared with white participants. Models include adjustment for gender. Solid lines represent incidence rate ratios and dashed lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

The incidence rates and multivariable adjusted IRRs are presented by ethnicity and age group in Table 3. African-Americans had the highest incidence rate for age 45 – 54 years (64.7 per 1000 person-years), 55 – 64 years (91.1 per 1000 person-years), and 65 – 74 years (117.6 per 1000 person-years), while Chinese participants had the highest incidence rate for age 75 – 84 years (131.1 per 1000 person-years). Compared with white participants, African-Americans and Hispanics ages 45 – 54 years had higher IRRs for hypertension after adjustment for age, gender, and MESA study site. Adjustment for baseline SBP and DBP attenuated these associations. Similarly, African-Americans ages 55 – 64 years and 65 – 74 years had higher IRRs for hypertension compared with whites after adjustment for age, gender, and MESA study site that were attenuated after additional multivariable adjustment including baseline SBP and DBP. In contrast, in the age 75 – 84 year group, the age, gender, and MESA study site adjusted IRRs for African-Americans and Hispanics were similar to white participants. Chinese participants in the age 75 – 84 year group had the highest incidence of hypertension, but this was not statistically significant compared with whites.

Table 3.

Incidence rates and adjusted incidence rate ratios (95% CI) for hypertension by ethnicity and age group

| Ethnicity | Number of participants | Crude incidence rate per 1000 person-years | Adjusted Incidence Rate Ratio (95% CI)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

| Age 45–54 years | |||||

| White | 508 | 32.7 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| African-American | 287 | 64.7 | 2.05 (1.47, 2.85) | 1.48 (1.01, 2.18) | 1.20 (0.81, 1.77) |

| Chinese | 166 | 28.6 | 0.99 (0.58, 1.68) | 0.96 (0.53, 1.74) | 0.79 (0.43, 1.43) |

| Hispanic | 335 | 43.7 | 1.30 (0.91, 1.88) | 0.94 (0.61, 1.45) | 0.84 (0.55, 1.28) |

| Age 55–64 years | |||||

| White | 409 | 59.1 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| African-American | 177 | 91.1 | 1.63 (1.20, 2.23) | 1.39 (0.98, 1.98) | 1.07 (0.75, 1.53) |

| Chinese | 130 | 57.7 | 1.07 (0.69, 1.64) | 1.21 (0.73, 2.00) | 1.03 (0.62, 1.69) |

| Hispanic | 217 | 67.3 | 1.18 (0.83, 1.68) | 0.84 (0.55, 1.28) | 0.77 (0.50, 1.18) |

| Age 65–74 years | |||||

| White | 320 | 73.6 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| African-American | 120 | 117.6 | 1.67 (1.21, 2.30) | 1.36 (0.94, 1.96) | 1.38 (0.95, 2.02) |

| Chinese | 100 | 68.9 | 0.95 (0.60, 1.51) | 0.83 (0.48, 1.43) | 0.78 (0.45, 1.34) |

| Hispanic | 132 | 102.5 | 1.44 (0.99, 2.11) | 1.14 (0.73, 1.80) | 1.10 (0.71, 1.73) |

| Age 75–84 years | |||||

| White | 121 | 113.4 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| African-American | 46 | 109.8 | 0.97 (0.56, 1.66) | 1.03 (0.56, 1.89) | 0.98 (0.53, 1.82) |

| Chinese | 28 | 131.1 | 1.40 (0.72, 2.73) | 1.88 (0.83, 4.26) | 1.94 (0.86, 4.41) |

| Hispanic | 50 | 125.9 | 1.27 (0.73, 2.20) | 1.67 (0.82, 3.38) | 1.65 (0.82, 3.38) |

Model 1 adjusted for age, gender, and MESA study site

Model 2 adjusted for variables in Model 1 plus education, body mass index, smoking status, alcohol consumption, depressive symptoms, Na/K ratio, diabetes, estimated glomerular filtration rate<60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, and parental history of hypertension

Model 3 adjusted for variables in Models 1 and 2 plus baseline systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure

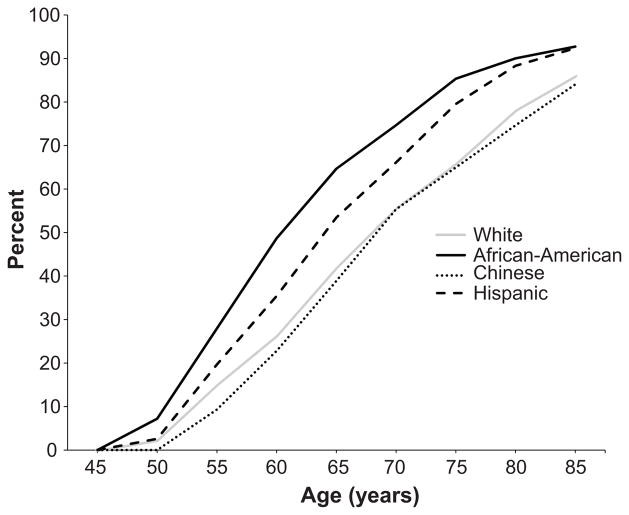

The estimated lifetime risk of hypertension, conditional on being free of hypertension at age 45 years, is presented by ethnicity in Figure 2. The lifetime risk of hypertension increased for all ethnicities with age. At all ages, African-Americans were more likely to be hypertensive than participants of other ethnic groups. For a 45-year old adult without hypertension, the 40 year risk of developing hypertension was 92.7% for African-Americans, 92.4% for Hispanics, 86.0% for whites, and 84.1% for Chinese adults.

Figure 2.

The estimated lifetime risk of hypertension for 45-year old white, African-American, Chinese, and Hispanic adults in the US based on data from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. These estimates are conditional on being free of hypertension at age 45 years and are adjusted for the competing risk of death.

DISCUSSION

In this multi-ethnic study of middle-aged and older adults, the incidence of hypertension was higher for African-Americans compared with whites between 45 – 74 years of age, but similar in these two groups after age 75 years. The incidence of hypertension was also higher among Hispanics than whites in middle-age, but similar at older ages. While the lifetime risk of hypertension increased with advancing age for all ethnicities, it was highest for African-Americans and Hispanics throughout middle-age and older adulthood, highlighting the importance of concerted prevention efforts throughout adulthood.

A higher prevalence of hypertension among African-American compared with white adults at all ages has been well-established,2, 3, 13, 24–26 but less is known about the incidence of hypertension. Several studies among young adults have reported higher hypertension incidence rates for African-Americans compared with whites. In the Bogalusa Heart Study, African-Americans had an increased risk of hypertension compared with whites after 15 years of follow-up from childhood to young adulthood.27 In the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study, a prospective cohort study of adults age 18–30 years at baseline, African-Americans had a higher incidence of hypertension compared with whites over a ten year follow-up period.6 Additionally, in the NHANES I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study, African-Americans had a higher incidence of hypertension than whites over 9.5 years of follow-up, with differences by age.7 At ages 25 – 34 years, the incidence of hypertension among African-American men and women (27.3% and 23.6%, respectively) were more than two times higher than white men and women (11.9% and 8.1%, respectively). Similar differences were also noted for the 35 – 54 year age group; however, hypertension incidence rates were similar among African-Americans and whites at ages 55 years and older.7

In a secondary analysis of clinical trial participants ages 30 – 54 years at baseline who were followed for 7 years, the incidence of hypertension was similar for African-Americans and whites.8 While the current study did not include participants < 45 years of age, African-Americans in the youngest age category (45 – 54 years) had a higher incidence of hypertension compared with whites. The contrasting findings among this age group may be due to several factors, including the study populations investigated and the hypertension definitions used. The previous study was a secondary analysis of clinical trial participants identified through an employer screening program in a single community,8 while the current study participants were from a population-based sample of multiple communities across the US.18 The eligibility criteria for clinical trials are more restrictive than observational studies, so the previous study may have limited generalizability. In contrast, MESA used a population-based approach for identification of participants. Also, the definition of hypertension used in the previous study applied higher blood pressure levels (≥160/95 mmHg), while the current study used a more contemporary definition of hypertension.28 In the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study, a prospective cohort study of adults ages 45 – 64 years at baseline, African-Americans had a higher overall incidence of hypertension, compared with whites over 3 years of follow-up.9 The ARIC study used the same definition of hypertension as applied in the current study and the higher incidence of hypertension for African-Americans compared with whites was present overall and within age strata (<50 years and ≥50 years) after 6 years of follow-up.29

Data from some studies have indicated Hispanics have a similar or lower prevalence of hypertension compared with whites, 2, 3, 10, 13, 30 although a higher prevalence among Hispanics has also been reported.16, 26 However, few studies have investigated incident hypertension. In the San Antonio Heart Study, the overall incidence of hypertension was similar among Mexican-Americans and non-Hispanic whites in crude and multivariable analyses.17 In age-specific analyses, the incidence of hypertension was higher among Mexican-Americans compared with non-Hispanic whites at ages 55–64 years. In contrast, Hispanics had a similar incidence of hypertension in age-specific analyses compared with whites in the San Luis Valley Diabetes study of adults ages 20–74 years.31 In the current study, Hispanics had a higher incidence of hypertension and a higher lifetime risk for hypertension compared with whites.

The incidence of hypertension has not been well investigated among Asians in the US, although prevalence data suggests Asians have a similar or lower prevalence of hypertension compared to whites.14, 16, 32 In the current study, the incidence of hypertension was similar for Chinese participants and whites overall and at age < 75 years. At age 75 – 84 years, Chinese participants had the highest crude incidence rate of hypertension of the four ethnic groups studied. After multivariable adjustment, Chinese participants had an increased risk of hypertension compared with whites although this association was not statistically significant and there was a limited sample size for this age group.

This study has several potential limitations. MESA was limited to adults ≥ 45 years of age and a high percentage of participants had prevalent hypertension at the baseline examination. Although a greater proportion of African-Americans were excluded with prevalent hypertension at baseline, the incidence rate for hypertension was higher for African-Americans compared with whites at ages 45 – 74 years and the lifetime risk for hypertension was higher among African-Americans through age 85 years. Also, the sample size was limited to fully investigate age-stratified associations. Additional studies with larger sample sizes are needed to evaluate ethnic differences in hypertension incidence, particularly at older ages. Lastly, acculturation factors (e.g., birthplace, years in the US) among Hispanic and Chinese participants were not investigated in the current study. Previous studies have reported differences in hypertension prevalence by birth place among Hispanics30, 33 and Asians,34 so the findings from the current study may not be generalizable to Hispanic and Asian subgroups.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the MESA study for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating MESA investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.mesa-nhlbi.org.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This research was supported by contracts N01-HC-95159 through N01-HC-95169 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None.

References

- 1.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2009: with special feature on medical technology. 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Egan B, Zhao Y, Axon R. US trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension, 1988–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:2043–2050. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ostchega Y, Dillon CF, Hughes JP, Carroll M, Yoon S. Trends in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control in older U.S. Adults: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1988 to 2004. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:1056–1065. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Voors A, Foster T, Frerichs R, Webber L, Berenson G. Studies of blood pressures in children, ages 5–14 years, in a total biracial community: The Bogalusa Heart Study. Circulation. 1976;54:319–327. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.54.2.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berenson GS, Wattigney WA, Webber LS. Epidemiology of hypertension from childhood to young adulthood in black, white, and hispanic population samples. Public Health Rep. 1996;111 (Suppl 2):3–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dyer AR, Liu K, Walsh M, Kiefe C, Jacobs DR, Jr, Bild DE. Ten-year incidence of elevated blood pressure and its predictors: The CARDIA Study. Coronary Artery Risk Development in (Young) Adults. J Hum Hypertens. 1999;13:13–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1000740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cornoni-Huntley J, LaCroix AZ, Havlik RJ. Race and sex differentials in the impact of hypertension in the united states. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:780–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He J, Klag MJ, Appel LJ, Charleston J, Whelton PK. Seven-year incidence of hypertension in a cohort of middle-aged African Americans and whites. Hypertension. 1998;31:1130–1135. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.5.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rywik SL, Williams OD, Pajak A, Broda G, Davis CE, Kawalec E, Manolio TA, Piotrowski W, Hutchinson R. Incidence and correlates of hypertension in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study and the Monitoring Trends and Determinants of Cardiovascular Disease (POL-MONICA) project. J Hypertens. 2000;18:999–1006. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200018080-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haffner SM, Mitchell BD, Stern MP, Hazuda HP, Patterson JK. Decreased prevalence of hypertension in Mexican-Americans. Hypertension. 1990;16:225–232. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.16.3.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ong K, Cheung B, Man Y, Lau C, Lam K. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension among United States adults 1999–2004. Hypertension. 2007;49:69–75. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000252676.46043.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sorel J, Ragland D, Syme S. Blood pressure in Mexican Americans, whites, and blacks. The Second National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134:370–378. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hajjar I, Kotchen T. Trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the United States, 1988–2000. JAMA. 2003;290:199–206. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao G, Ford ES, Mokdad AH. Racial/ethnic variation in hypertension-related lifestyle behaviours among US women with self-reported hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 2008;22:608–616. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2008.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ye J, Rust G, Baltrus P, Daniels E. Cardiovascular risk factors among Asian Americans: Results from a national health survey. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19:718–723. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lloyd-Jones DM, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Patel AS, Matthews KA, Pasternak RC, Everson-Rose SA, Scuteri A, Chae CU. Ethnic variation in hypertension among premenopausal and perimenopausal women: Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Hypertension. 2005;46:689–695. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000182659.03194.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haffner SM, Mitchell BD, Valdez RA, Hazuda HP, Morales PA, Stern MP. Eight-year incidence of hypertension in Mexican-Americans and non-Hispanic whites. The San Antonio Heart Study. Am J Hypertens. 1992;5:147–153. doi: 10.1093/ajh/5.3.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, Detrano R, Diez Roux AV, Folsom AR, Greenland P, Jacob DR, Jr, Kronmal R, Liu K, Nelson JC, O’Leary D, Saad MF, Shea S, Szklo M, Tracy RP. Multi-ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis: objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:871–881. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA) field center manual of operations. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Block G, Woods M, Potosky A, Clifford C. Validation of a self-administered diet history questionnaire using multiple diet records. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43:1327–1335. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90099-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levey A, Bosch J, Lewis J, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: A new prediction equation. Modification of diet in renal disease study group. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:461–470. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beiser A, D’Agostino RS, Seshadri S, Sullivan L, Wolf P. Computing estimates of incidence, including lifetime risk: Alzheimer’s disease in the Framingham Study. The practical incidence estimators (pie) macro. Stat Med. 2000;19:1495–1522. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000615/30)19:11/12<1495::aid-sim441>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sprafka JM, Folsom AR, Burke GL, Edlavitch SA. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors in blacks and whites: The Minnesota Heart Survey. Am J Public Health. 1988;78:1546–1549. doi: 10.2105/ajph.78.12.1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Svetkey LP, George LK, Burchett BM, Morgan PA, Blazer DG. Black/white differences in hypertension in the elderly: An epidemiologic analysis in central north carolina. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137:64–73. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kramer H, Han C, Post W, Goff D, Diez-Roux A, Cooper R, Jinagouda S, Shea S. Racial/ethnic differences in hypertension and hypertension treatment and control in the Multi-ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Am J Hypertens. 2004;17:963–970. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bao W, Threefoot S, Srinivasan S, Berenson G. Essential hypertension predicted by tracking of elevated blood pressure from childhood to adulthood: The Bogalusa Heart Study. Am J Hypertens. 1995;8:657–665. doi: 10.1016/0895-7061(95)00116-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT, Jr, Roccella EJ. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206–1252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fuchs FD, Chambless LE, Whelton PK, Nieto FJ, Heiss G. Alcohol consumption and the incidence of hypertension: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Hypertension. 2001;37:1242–1250. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.5.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lorenzo C, Serrano-Rios M, Martinez-Larrad MT, Gabriel R, Williams K, Gonzalez-Villalpando C, Stern MP, Hazuda HP, Haffner S. Prevalence of hypertension in Hispanic and non-Hispanic white populations. Hypertension. 2002;39:203–208. doi: 10.1161/hy0202.103439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shetterly SM, Rewers M, Hamman RF, Marshall JA. Patterns and predictors of hypertension incidence among Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites: The San Luis Valley Diabetes Study. Journal of Hypertension. 1994;12:1095–1102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balluz LS, Okoro CA, Mokdad A. Association between selected unhealthy lifestyle factors, body mass index, and chronic health conditions among individuals 50 years of age or older, by race/ethnicity. Ethn Dis. 2008;18:450–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moran A, Roux AV, Jackson SA, Kramer H, Manolio TA, Shrager S, Shea S. Acculturation is associated with hypertension in a multiethnic sample. Am J Hypertens. 2007;20:354–363. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klatsky A, Armstrong M. Cardiovascular risk factors among Asian Americans living in northern California. Am J Public Health. 1991;81:1423–1428. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.11.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.United States Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, Mozaffarian D, Appel LJ, Van Horn L, Greenlund K, Daniels S, Nichol G, Tomaselli GF, Arnett DK, Fonarow GC, Ho PM, Lauer MS, Masoudi FA, Robertson RM, Roger V, Schwamm LH, Sorlie P, Yancy CW, Rosamond WD. Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: The American Heart Association’s strategic impact goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation. 2010;121:586–613. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Appel LJ, Champagne CM, Harsha DW, Cooper LS, Obarzanek E, Elmer PJ, Stevens VJ, Vollmer WM, Lin PH, Svetkey LP, Stedman SW, Young DR. Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on blood pressure control: Main results of the Premier clinical trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2083–2093. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.16.2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Whelton PK, He J, Appel LJ, Cutler JA, Havas S, Kotchen TA, Roccella EJ, Stout R, Vallbona C, Winston MC, Karimbakas J. Primary prevention of hypertension: Clinical and public health advisory from the national high blood pressure education program. JAMA. 2002;288:1882–1888. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.15.1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]