Abstract

Objective To compare the effect of evidence based information on risk with that of standard information on informed choice in screening for colorectal cancer.

Design Randomised controlled trial with 6 months’ follow-up.

Setting German statutory health insurance scheme.

Participants 1577 insured people who were members of the target group for colorectal cancer screening (age 50-75, no history of colorectal cancer).

Interventions Brochure with evidence based risk information on colorectal cancer screening and two optional interactive internet modules on risk and diagnostic tests; official information leaflet of the German colorectal cancer screening programme (control).

Main outcome measure The primary end point was “informed choice,” comprising “knowledge,” “attitude,” and “combination of actual and planned uptake.” Secondary outcomes were “knowledge” and “combination of actual and planned uptake.” Knowledge and attitude were assessed after 6 weeks and combination of actual and planned uptake of screening after 6 months.

Results The response rate for return of both questionnaires was 92.4% (n=1457). 345/785 (44.0%) participants in the intervention group made an informed choice, compared with 101/792 (12.8%) in the control group (difference 31.2%, 99% confidence interval 25.7% to 36.7%; P<0.001). More intervention group participants had “good knowledge” (59.6% (n=468) v 16.2% (128); difference 43.5%, 37.8% to 49.1%; P<0.001). A “positive attitude” towards colorectal screening prevailed in both groups but was significantly lower in the intervention group (93.4% (733) v 96.5% (764); difference −3.1%, −5.9% to −0.3%; P<0.01). The intervention had no effect on the combination of actual and planned uptake (72.4% (568) v 72.9% (577); P=0.87).

Conclusions Evidence based risk information on colorectal cancer screening increased informed choices and improved knowledge, with little change in attitudes. The intervention did not affect the combination of actual and planned uptake of screening.

Trial registration Current Controlled Trials ISRCTN47105521.

Introduction

Recommendations on screening for cancer, even if published by an independent scientific panel, can stir up political tempests and provoke harsh criticism from influential medical groups.1 A key factor in the argument between advocates and critics of screening is the way in which information about benefit and harm is communicated.2 Public campaigns, such as the one run by the powerful Felix Burda Foundation on screening for colorectal cancer in Germany, use persuasive information.3 Opponents underscore the ethical aspects and possible harm of screening, demanding evidence based information and informed choices.2 Although policies in Germany and elsewhere increasingly assert that participation in screening should reflect “informed choice,” this change in approach has not yet been translated into practice. An unspoken concern is that understandable, unbiased, and complete information may deter people from participating in screening. A recent editorial by Bekker in this journal has shown how common these worries still are, even among experts and proponents of informed choice and shared decision making.4 The article revived the dispute on the morals and ethics of information processes in cancer screening programmes, but the effect of evidence based information on screening for cancer remains poorly understood.

At the start of this project, we surveyed criteria for evidence based information for patients and consumers and critically appraised available print and web based information on screening for colorectal cancer.5 6 We did not identify any material, presented in an unbiased and understandable way, that provided the information defined by guidelines on ethics.5 7 8 Cancer screening programmes target the healthy population. Some people will benefit, but more will have positive test results, receive needless treatment, or live more years as a patient with cancer. Ethics guidelines emphasise that evidence based information must not be withheld if decline of screening is anticipated.7 8

Screening programmes that were implemented well before that for colorectal cancer have done no better. In 2006 Jørgensen and Gøtzsche published a survey on the quality of information used in mammography screening programmes. The major harm of screening was not mentioned in any of 31 invitations.9 In 2009 the same authors found that little had changed.2 Recently, Gigerenzer and colleagues reported a continuing dramatic overestimation of the possible benefit of mammography and prostate specific antigen testing in the vast majority of women and men, in all countries surveyed.10 Misconceptions were very pronounced in regions with screening programmes and when physicians or pharmacists were used as additional sources of information. The basis for informed decisions in cancer screening is largely non-existent in Europe.10

We designed this study to compare the effect of evidence based information on risk of screening for colorectal cancer with that of standard information. We tested the hypothesis that informed choices would be higher after receipt of evidence based risk information.

Methods

We recruited people insured by a large German statutory health insurance scheme, the Gmünder Ersatzkasse (GEK), who were members of the target group for colorectal cancer screening in Germany (age 50-75, no history of colorectal cancer). Considering these inclusion criteria, we drew a random sample of about 4000 people from the health insurance scheme’s data pool. In August 2008 this sample received information and a consent form asking them to participate in a study that compared two different formats of information for patients about screening for colorectal cancer. This first round did not achieve the calculated sample size, so we repeated the procedure in November 2008 and again approached about 4000 insured people. We thus achieved a study group of 1586 people, which exceeded the planned sample size of 1140. We randomised all who gave informed consent. No further change to the original study protocol occurred.

Randomisation and blinding

We randomly assigned the 1586 participants to receive either of the two formats of information on colorectal cancer screening. We assigned members from the same household to receive the same information (n=6). An external person randomised all participants on 28 December 2008, using a computer generated sequence of blocks of 10 participants’ identity numbers. Allocation was concealed. Identity numbers were independent of allocation, and study members did not have access to the data. Trial staff who sent out questionnaires and reminder letters and entered data were unaware of the study arm to which participants had been assigned, as was the statistician. We excluded nine participants who withdrew informed consent at the beginning of the study.

Intervention

The evidence based information on risk of colorectal cancer screening aims to enhance informed decision making. It is a brochure of 38 pages. Topics cover personalised risk of colorectal cancer, all available screening options with possible benefit and harm, including the option not to screen, and prevention of colorectal cancer. In addition, participants had access to two interactive internet modules on “risk” and “diagnostic tests.” These internet modules did not add extra information but offered the opportunity to read more on the topic. We did not, therefore, survey use of the internet modules. In designing and evaluating the information material, we followed the UK Medical Research Council’s framework for complex interventions.11 We compiled the information by using the best available evidence. The ethics guidelines of the General Medical Council and criteria for evidence based information guided the selection of information.5 7 8 12 This meant, for example, that information was presented as natural frequencies rather than changes in relative risk, with comparable reference populations and timeframes. We involved members of the target group in the development process from the beginning. We pilot tested the brochure in focus groups to assess comprehensibility, readability, and acceptability.13 14 In addition, two leading German gastroenterologists reviewed the information. Finally, we revised the brochure. We updated the information in April 2008. During the study period, the brochure was available only to members of the intervention group. The brochure and the interactive modules are now generally accessible on the internet (brochure: www.gesundheit.uni-hamburg.de/upload/AltDarmkrebsinternet.pdf; modules: www.gesundheit.uni-hamburg.de/cgi-bin/newsite/index.php?page=page_331).

Comparison

The comparison was the official information leaflet of the German national colorectal cancer screening programme. The information was published in 2003 and is still in use.15 This standard information delineates the two options for colorectal cancer screening—faecal occult blood test and colonoscopy. No quantitative information on individual risk or benefit is included, and harm is incompletely communicated. The two tests are part of the national quality assured colorectal cancer screening programme. Up to now, this screening programme has not included active invitations or sending of test kits. People can choose either one of these tests: from age 50 to 55 years, faecal occult blood test every year; from age 56, either faecal occult blood test every two years or colonoscopy every 10 years, up to two colonoscopies.

Procedure

In January 2009 we sent participants either the intervention brochure or the comparison information. At the same time, we drew baseline data from the database of the health insurance scheme. We assessed demographic characteristics that were not available in the database at follow-up.

After six weeks, in February 2009, participants received a questionnaire to assess “knowledge” and “attitude,” two dimensions of the primary outcome. Participants also received a prepaid envelope. Two reminder letters were sent out, including a new copy of the questionnaire. Six months later, in July 2009, we sent a second questionnaire to assess the combination of actual and planned uptake of screening. Again, two reminder letters were sent out.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was “informed choice,” as described by Marteau et al.16 We classified choices about colorectal cancer screening as “informed” and “uninformed,” according to participants’ knowledge about screening, their attitudes towards screening, and whether they had colorectal cancer screening.16 We classified participants with good knowledge and positive attitude who had screening as making an informed choice. We also classified participants with good knowledge and a negative attitude who did not have screening as making an informed choice.

We translated and re-translated the instrument developed by Marteau et al. We adapted the knowledge questionnaire to screening for colorectal cancer. We pilot tested the questionnaire in a separate sample of 62 people in the target group for colorectal cancer screening, using the same inclusion criteria as in the main trial. We did 22 interviews, applying the “think aloud” method. After revision, questionnaires were sent out with the evidence based risk information (n=20) and the standard information (n=20). This evaluation step did not result in further revision of the questionnaire.

We coded questionnaires according to a predefined coding sheet.16 Each correct response scored one point, leading to a maximum score of eight points. We counted missing responses as wrong answers. We rated participants as having good knowledge if they had a score of at least 4. We deemed participants to have a positive attitude if they had a score below 2.5 (maximum score 4). We assessed the combination of actual and planned uptake by two questions. As the timeframes in the colorectal cancer screening programme in Germany would exceed any study period (10 years for colonoscopy screening and one to two years for occult blood test, depending on age), uptake comprised the combination of actual and planned uptake. As knowledge is a prerequisite to achieve the category “informed choice,” we decided to analyse knowledge as a secondary outcome. In addition, we defined “combination of actual and planned uptake” as a secondary outcome.

We had decided not to assess components of the outcome measures at baseline for methodological reasons. Applying the same questionnaires twice within six weeks would have biased results.

Statistical analysis

For the sample size calculation, we assumed that about 10% of the target group would make an informed decision when using standard information. We considered an increase of 10% of participants making an informed decision to be an important improvement. Aiming for a power of 90% at an α error of 1%, we therefore needed 397 participants in each study group. Taking into account a non-responder rate of 30% would result in a sample size of at least 1140 participants.

We did the primary analysis according to intention to treat, using the full analysis set. The variables considering knowledge did not contain any missing values because we counted only correct answers as knowledge. We imputed missing values individually in the binomial outcomes of attitude (positive/negative) and combination of actual and planned uptake (yes/no) in the following manner. We imputed missing values in some items of attitude by using auxiliary variables of similar content. We imputed the remaining missing values in the dichotomous variable attitude by random numbers from a binomial distribution by using the estimated probability on the subpopulation without missing values. In the same manner, we imputed missing values of the variable “combination of actual and planned uptake” by using binomially distributed random numbers. We calculated the primary outcome of informed choice from the variables “good knowledge,” “positive/negative attitude,” and “combination of actual and planned uptake yes/no” after imputation of missing values. In total, we imputed 219 missing values into informed choice. Additionally, we did a per protocol analysis excluding participants with any missing values for the main outcome.

We present baseline variables as means and standard deviation or frequency distributions. We analysed the primary outcome by comparing the probabilities of informed choice between the intervention and control group by Fisher’s exact test with a two sided significance level of 1%. We estimated the difference of the probabilities and a 99% confidence interval. We analysed the secondary outcomes good knowledge, positive attitude, and combination of actual and planned uptake in the same manner.

We also analysed knowledge and attitude scores as continuous variables and presented them as means (SD). We used Wilcoxon’s rank sum test to compare groups, excluding participants with missing values. In these additional analyses, the confidence level was 5%. All tests were two sided. We used SAS version 9.2 for statistical calculations.

In January 2011 we did additional post-hoc analyses of health insurance data on uptake of screening for colorectal cancer on the basis of physicians’ claims. We provide information on faecal occult blood test and colonoscopy as documented for the three years before the study and for the six months after the intervention, using the same methods as above.

Results

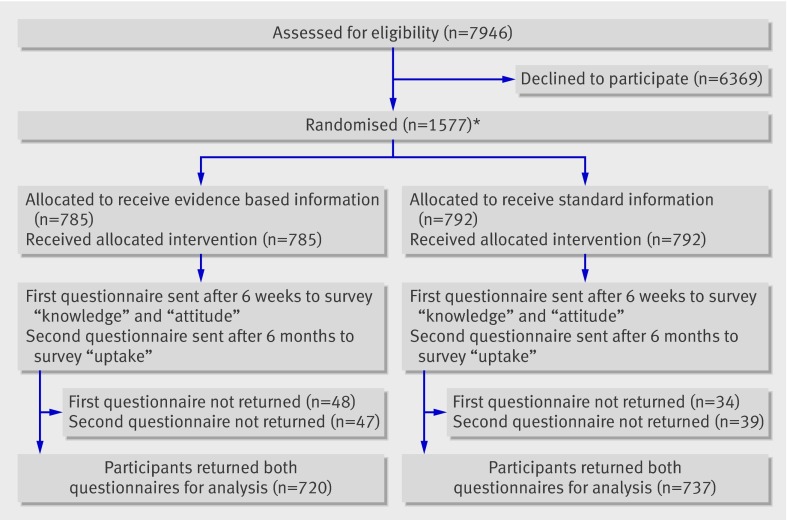

The baseline characteristics of eligible insured people who agreed to participate in this study on the comparison of different screening information formats (n=1577) were comparable in terms of sex and age to those of people who declined (n=6369): women 42.7% (673/1577) versus 43.3% (2760/6369); mean age 61.2 (SD7.0) versus 60.7 (7.3). However, according to insurance scheme data, people who declined were less likely to have a documented screening occult blood test (48.1% (759/1577) v 36.1% (2297/6369)) or screening colonoscopy (13.6% (215/1577) v 6.8% (434/6369)) during the three year pre-study period. We analysed informed choice for 1577 of 1586 randomised participants (figure).

Flow of participants through trial. *At start of study 9/1586 randomised participants withdrew informed consent and were therefore excluded

Overall, 1457 (92.4%) participants returned both questionnaires; 48 (3.0%) did not return any questionnaire. The remaining 72 (4.6%) participants returned one of the questionnaires. Baseline characteristics of the two groups were comparable (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristic | Evidence based risk information (n=785) | Standard information (n=792) |

|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 349 (44.5) | 324 (40.9) |

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 60.8 (6.9) | 61.5 (7) |

| Age group (years): | ||

| 50-59 | 377 (48.0) | 351 (44.3) |

| 60-69 | 297 (37.8) | 308 (38.9) |

| 70-79 | 111 (14.1) | 133 (16.8) |

| Education: | (n=703) | (n=733) |

| No qualification | 2 (0.3) | 3 (0.4) |

| Secondary school 9 years | 345 (49.1) | 402 (54.8) |

| Secondary school 10 years | 242 (34.4) | 218 (29.7) |

| General Certificate of Education A Level | 114 (16.2) | 110 (15.0) |

| First language German | 712/732 (97.3) | 724/744 (97.3) |

| Occupational status: | (n=693) | (n=714) |

| Untrained | 25 (3.6) | 39 (5.5) |

| Vocational training | 595 (85.9) | 603 (84.5) |

| University graduate | 73 (10.5) | 72 (10.1) |

| Employed | 348/738 (47.2) | 317/753 (42.1) |

| Household income: | (n=671) | (n=690) |

| <500-1500 € | 140 (20.9) | 147 (21.3) |

| 1500-3000 € | 389 (58.0) | 419 (60.7) |

| 3000->5000 € | 142 (21.2) | 124 (18.0) |

| Screening during 3 years before study: | ||

| Occult blood test | 376 (47.9) | 383 (48.4) |

| Colonoscopy | 105 (13.4) | 110 (13.9) |

Recipients of evidence based risk information were much more likely to make informed choices than were recipients of standard information (44.0% (345/785) v 12.8% (101/792); difference 31.2%, 99% confidence interval 25.7% to 36.7%; P<0.001). Table 2 summarises the analyses of the single dimensions of the primary outcome. Significantly more participants in the intervention group than in the control group had good knowledge (59.6% (468/785) v 16.2% (128/792); difference 43.5%, 37.8% to 49.1%; P<0.001). The mean knowledge score (score 0-8) in the intervention group was 4.3 (SD 2.3) compared with 2.5 (1.2) in the control group (P<0.001). Table 3 shows the results for the multiple choice items assessing knowledge. Positive attitude was significantly lower in the intervention group than in the control group (93.4% (733/785) v 96.5% (764/792); difference −3.1%, −5.9% to −0.3%; P<0.01). The mean attitude score was 1.4 (0.6) in the intervention group and 1.3 (0.5) in the control group (P<0.001) (missing values 93 v 88). The difference in self reported combination of actual and planned uptake was not statistically significant (72.4% (568/785) v 72.9% (577/792); difference −0.5%, −6.3 to 5.3; P=0.87). Per protocol analysis did not affect these findings (data not shown). Missing values thus seem unlikely to have affected our conclusions.

Table 2.

Primary outcome (informed choice) at six months’ follow-up and dimensions of informed choice: knowledge, attitude, and uptake. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Outcome | Evidence based information (n=785) | Standard information (n=792) | % difference (99% CI); P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Informed choice | 345 (44.0) | 101 (12.8) | 31.2 (25.7 to 36.7); <0.001 |

| Good knowledge* | 468 (59.6) | 128 (16.2) | 43.5 (37.8 to 49.1); <0.001 |

| Positive attitude* | 733 (93.4) | 764 (96.5) | −3.1 (−5.9 to −0.3); <0.01 |

| Uptake of colorectal cancer screening† | 568 (72.4) | 577 (72.9) | −0.5 (−6.3 to 5.3); 0.87 |

*After six weeks.

†Combination of actual and planned uptake after six months.

Table 3.

Multiple choice items of knowledge questionnaire (possible answers in parentheses). Values are numbers (percentages) with correct answers

| Item of knowledge | Evidence based information (n=785) | Standard information (n=792) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Which disease is the occult blood test (for example, Haemoccult) supposed to detect? (irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, colorectal cancer*, haemorrhoids) | 632 (80.5) | 623 (78.7) |

| 2. When can an occult blood test lead to a false positive test result? If on the day before the test (one consumed raw meat*, one consumed fish, one drunk alcohol, one smoked cigarettes) | 655 (83.4) | 632 (79.8) |

| 3. Imagine 1000 people in your age group who have positive test results in their occult blood test. How many out of these 1000 people really have colorectal cancer?† (1000, 980, 700, 400* (age 60-79), 100* (age 50-59), 10) | 369 (47.0) | 177 (22.3) |

| 4. The risk for colorectal cancer increases with age. How high do you estimate the risk for colorectal cancer to be in your age group during the next 10 years?† (1 in 761, 1 in 237* (age 50-59), 1 in 92* (age 60-69), 1 in 38* (age 70-79), 1 in 18) | 392 (49.9) | 207 (26.1) |

| 5. Screening with the occult blood test decreases the risk of dying from colorectal cancer. Imagine 1000 people start from age 50 to regularly participate in the screening programme. How many fewer people do you estimate would die from colorectal cancer? (1-2*, 8-10, 50-100, 200-400, 800-990) | 305 (38.9) | 29 (3.7) |

| 6. For colorectal cancer screening, either the occult blood test or colonoscopy may be used. It is important that studies are available that have investigated the benefit and harm of these medical tests. Please rate whether such studies are available for these tests. (“yes*/no” for occult blood test; “yes/no*” for colonoscopy) | 194 (24.7) | 52 (6.6) |

| 7. Imagine 1000 people in your age group who have negative test results in their occult blood test. Please rate how many out of these 1000 people really do not have colorectal cancer† (1000, 999* (age 50-59), 990* (age 60-79), 850, 400, 100, 10) | 376 (47.9) | 152 (19.2) |

| 8. Colonoscopy may be associated with severe side effects. Please rate what side effects may occur with colonoscopy. Please mark all correct answers. (faecal incontinence, bleeding*, bowel occlusion, bowel perforation*, death*) | 437 (55.7) | 103 (13.0) |

*Correct answer.

†Items analysed according to age of participants.

Health insurance data on actual uptake support the lack of difference in the combination of actual and planned uptake up to six months after the intervention. A screening faecal occult blood test was documented for 18.0% (141/785) of the intervention group compared with 16.9% (134/792) of the control group (difference 1%, −3.9% to 6.0%; P=0.60), and screening colonoscopy was documented for 3.8% (30/785) versus 3.4% (27/792) (difference 0.4%, −2.0 to 2.8%; P=0.69).

Discussion

An evidence based brochure on screening for colorectal cancer significantly increased the proportion of participants who made informed choices. Uptake of screening for colorectal cancer was not affected. Positive attitudes were predominant in both the intervention and control groups.

Strengths and limitations of study

The evidence based risk information studied in this trial has been developed and evaluated according to the UK Medical Research Council’s framework for complex interventions.11 In phase 1, we systematically analysed the available information material on screening for colorectal cancer, surveyed the preferences and information needs of the target group, processed the content according to the standards of evidence based medicine, and modelled the intervention.5 6 13 In phase 2, we pilot tested the first draft for readability, comprehensibility, completeness, and acceptance, and we commissioned two expert reviews.13 14 17 Phase 3 comprises the evaluation in a randomised controlled trial presented here.11

The trial design was rigorous for several reasons. Blinding of randomisation, study participants, assessment of outcome measures, and analyses minimised bias. Attrition rates were very low, and the primary analysis was on intention to treat. The educational background of the study participants was, if anything, below the average of the German population,18 and we had a predominance of men corresponding to the structure of people insured by the cooperating statutory health insurance scheme as well as the risk distribution of colorectal cancer.

The trial also has limitations. Study participants were more likely to take part in colorectal cancer screening than were insured people who showed no interest in participating in this investigation on the effects of two different formats of information on screening. However, these findings are unlikely to have affected the primary outcome of informed choice. We also do not expect relevant differential effects on the secondary outcomes of combination of actual and planned uptake and attitude. As we showed in a former study of citizens of Hamburg, even recruitment strategies that did not disclose any relation to health topics led to samples extremely in favour of cancer screening.14 Because of screening intervals of two years for occult blood testing and 10 years for colonoscopy, we rated uptake as the combination of actual and planned uptake of screening. In Germany, claims data from health insurance schemes are not available until about nine months after the event. However, post hoc analyses of health insurance data support the lack of effects on actual uptake. In addition, all data are limited by the imprecision inherent to questionnaire surveys. Finally, we were not able to evaluate possible adverse effects.

Meaning of results

Our results support and extend the findings of other trials. A recently updated literature search identified some new publications on related topics. Fox identified nine studies on information material used in screening programmes.19 Whereas five out of eight trials assessing knowledge showed increased knowledge, only one of those assessing attitude showed any change in attitude towards a more negative screening attitude.19 In contrast, Krist et al found that a decision aid enhanced knowledge and decreased uptake in prostate cancer screening.20

Our study adds important new knowledge, as the outcome measure of informed choice has scarcely been studied. None of the trials included in the review of Fox assessed this outcome.19 Mathieu et al studied the effect on informed choices of a decision aid on mammography for 70 year old women.21 The decision aid significantly increased informed choices and also knowledge; uptake was not affected.21 A recently published trial by Trevena et al also found that a decision aid on screening for colorectal cancer increased informed choices without affecting uptake.22 Marteau et al assessed the effect of an evidence based invitation on screening for diabetes.23 The intervention did not reduce uptake of screening.23 The lack of effect of improved knowledge about risk on uptake of screening in our study may be due to the overall high level of positive attitudes towards cancer screening in Germany and rejection of risk information for reasons of cognitive dissonance.14

While this manuscript was going through the review process, Smith et al published their evaluation of a decision aid on occult blood screening in adults with low education in the Australian screening programme.24 Test kits were posted to both study groups. The authors assessed the primary outcomes “informed choice” and “preferences for involvement in the screening decision” in a telephone interview two weeks after the intervention. The decision aid significantly increased informed choice and knowledge and also reduced the participation rate compared with standard information.24 The accompanying editorial raised concerns that uncritical acceptance of initiatives to promote informed choice may cause more harm than good; it may rather facilitate adherence to testing, once efficacy has been shown to reduce mortality.4 The editorial elicited a dispute on ethics in screening programmes and the roles of shared decision making and patients’ autonomy.25 26

In contrast, the German screening programme includes neither active invitations nor the posting of test kits. Therefore, the fact that a high number of insured people who were asked to take part in our study on different formats of screening information showed no interest in participating was not unexpected. As Dalton pointed out, health screening is elevated to a moral good for public health practitioners, whereas for the autonomous other (patient) it is just a lifestyle choice.25

Implications for policy makers and clinicians

In a healthcare system, providing quality assurance and the opportunity to access evidence based health information would be expected to increase informed choice without changing uptake of screening for colorectal cancer. Our results support the ethics guidelines’ demand for evidence based, reliable, and easy to understand information on the benefit and harm of screening interventions. Such information has to target informed choices. Campaigns using misleading presentations of information are delusive and should be abandoned.

Remarkably, the evidence based risk information used here achieved a relevant increase in informed choices without additional interventions. Counselling was not provided. The brochure may now be downloaded from the internet (brochure: www.gesundheit.uni-hamburg.de/upload/AltDarmkrebsinternet.pdf; modules: www.gesundheit.uni-hamburg.de/cgi-bin/newsite/index.php?page=page_331). Meanwhile, the criteria for evidence based information on cancer screening which had been applied to the tested information have been defined as a standard by the German Network for Evidence Based Medicine.27

People and organisations designing and implementing screening programmes should respect the ethical right of consumers for evidence based information and informed choices.

What is already known on this topic

Information for patients on cancer screening is often biased, incomplete, and persuasive

Guidelines on ethics promote evidence based information and informed choices

The effects of evidence based information in cancer screening are incompletely understood

What this study adds

When standard information is used, very few people make an informed choice on screening for colorectal cancer

A simple evidence based brochure without additional counselling may substantially increase informed choices

Increasing knowledge of risk had little effect on attitude and no effect on uptake of screening within six months

We thank Susanne Kählau-Meier for valuable organisational assistance and Thomas Schürholz, Stefan Dudey, and Rainer Willaredt from the Gmünder Ersatzkasse for excellent cooperation.

Contributors: AS was the principal investigator. AS and IM developed the idea for the study. All authors contributed to the study design, data analysis, and interpretation of the results and commented on the draft. AS and CH carried out the study. BH did statistical analyses. AS drafted the manuscript. IM critically revised the manuscript. All authors had full access to all data. AS is the guarantor.

Funding: German Federal Ministry of Education and Research.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: The local ethics committee of Hamburg approved the study protocol in June 2008 (ref: PV2955).

Data sharing: The study protocol and related material are available from the authors on request.

Cite this as: BMJ 2011;342:d3193

References

- 1.Eggen D, Stein R. Mammograms and politics: task force stirs up a tempest. Washington Post. 18 November 2009.

- 2.Gøtzsche PC, Hartling OJ, Nielsen M, Brodersen J, Jørgensen KJ. Breast screening: the facts—or maybe not. BMJ 2009;338:b86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Felix Burda Foundation. Campaign 2010. www.felix-burda-stiftung.de/kampagne-2011/index.php.

- 4.Bekker HL. Decision aids and uptake of screening. BMJ 2010;341:c5407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steckelberg A, Berger B, Köpke S, Heesen C, Mühlhauser I. [Criteria for evidence-based patient information] [German]. Z Arztl Fortbild Qualitatssich 2005;99:343-51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steckelberg A, Balgenorth A, Mühlhauser I. [Analysis of German language consumer information brochures on screening for colorectal cancer] [German]. Z Arztl Fortbild Qualitatssich 2001;95:535-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.General Medical Council. Protecting patients, guiding doctors. Seeking patients’ consent: the ethical considerations. 1999. www.gmc-uk.org/Seeking_patients_consent_The_ethical_considerations.pdf_25417085.pdf

- 8.General Medical Council. Consent guidance: patients and doctors making decisions together. 2008. www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/ethical_guidance/consent_guidance_index.asp.

- 9.Jørgensen KJ, Gøtzsche PC. Content of invitations to publicly funded screening mammography. BMJ 2006;332:538-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gigerenzer G, Mata J, Frank R. Public knowledge of benefits of breast and prostate cancer screening in Europe. J Natl Cancer Inst 2009;101:1216-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.UK Medical Research Council. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: new guidance. 2008. www.mrc.ac.uk/Utilities/Documentrecord/index.htm?d=MRC004871.

- 12.Bunge M, Mühlhauser I, Steckelberg A. What constitutes evidence-based patient information? Overview of discussed criteria. Patient Educ Couns 2010;78:316-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steckelberg A, Kasper J, Redegeld M, Mühlhauser I. Risk information—barrier to informed choice? A focus group study. Soz Praventivmed 2004;49:375-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steckelberg A, Kasper J, Mühlhauser I. Selective information seeking: can consumers’ avoidance of evidence-based information on colorectal cancer screening be explained by the theory of cognitive dissonance? Ger Med Sci 2007;5:Doc05. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Federal Joint Committee. Richtlinien des Bundesausschusses der Ärzte und Krankenkassen über die Früherkennung von Krebserkrankungen (Krebsfrüherkennungs-Richtlinien) [German]. Dtsch Ärztebl 2003;11:518-21. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marteau T, Dormandy E, Michi S. A measure of informed choice. Health Expect 2001;4:99-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steckelberg A. [Evidence-based information for patients and consumers using colorectal cancer as an example: suggestions for improving informed decision making] [German]. University of Hamburg, 2005.

- 18.German Federal Statistical Office. Homepage. 2010. www.destatis.de.

- 19.Fox R. Informed choice in screening programmes: do leaflets help? A critical literature review. J Public Health 2006;28:309-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krist AH, Woolf SH, Johnson RE, Kerns JW. Patient education on prostate cancer screening and involvement in decision making. Ann Fam Med 2007;5:112-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathieu E, Barratt A, Davey HM McGeechan K, Howard K, Houssami N. Informed choice in mammography screening: a randomized trial of a decision aid for 70-year-old women. Arch Intern Med 2007;22:2039-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trevena LJ, Barratt A, Irwig L. Randomized trial of a self-administered decision aid for colorectal cancer screening. J Med Screen 2008;15:76-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marteau TM, Mann E, Prevost AT, Vasconcelos JC, Kellar I, Sanderson S, et al. Impact of an informed choice invitation on uptake of screening for diabetes in primary care (DICISION): randomised trial. BMJ 2010;340:c2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith SK, Trevena L, Simpson JM, Barratt A, Nutbeam D, McCaffery KJ. A decision aid to support informed choices about bowel cancer screening among adults with low education: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010;341:c5370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dalton CB. Decision aids and screening: editorial was amoral. BMJ 2010;341:c6648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hudson B. Decision aids and screening: information v promotion. BMJ 2010;341:c6650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klaus K, Mühlhauser I, for the German Network of Evidence-based Medicine. [Criteria for the development of patient information on cancer screening] [German]. 2008 (available at www.ebm-netzwerk.de/netzwerkarbeit/images/stelungnahme_dnebm_080630.pdf).