Abstract

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE) is a heritable systemic disorder characterized by calcification of the elastic fibers of the connective tissue. Symptoms are predominantly noted in the eye, the skin, and the cardiovascular system, resulting in visual loss, skin lesions, and life-threatening vascular disease. In this study we combined homozygosity mapping and genome scanning with 374 markers in affected individuals from a PXE family from a genetically isolated population in The Netherlands. Initial homozygosity in two or three patients was found with up to 20 markers, among which D16S292 located in 16p13.1. Upon refined and more extensive family screening of the latter region, close linkage without recombination was found with the marker D16S764 (Zmax = 6.27). Despite clear autosomal recessive inheritance of the ocular symptoms in PXE, vascular symptoms appear in 40%–50% of the heterozygotes.

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE) is a rare heritable disorder of the connective tissue. Histopathological findings show primarily calcification of the elastic fibers, next to abnormalities of the collagen fibrils (Hausser and Anton-Lamprecht 1991). The clinical manifestation is highly variable with delayed onset and variable expression of the symptoms within families. Although the disease may affect many organs, it characteristically involves the Bruch’s membrane in the eye, the skin, and the vascular system (Goodman et al. 1963; Neldner 1988a,b; Lebwohl et al. 1993). Associated ocular findings include angioid streaks, diffuse mottling of the retina referred to as peau d’orange, optic nerve drusen, peripheral retinal scars, as well as macular degeneration due to leaking subretinal neovascularization (Bressler et al. 1987; Mansour et al. 1988). Affected individuals experience characteristic changes of the skin in the neck region, described as “plucked chicken appearance,” associated with loose and slightly thickened skin. The skin lesions are generally not noted until the second or third decade and can be verified by a skin biopsy. Cardiovascular involvement is common, and PXE patients typically present with arteriosclerosis, hypertension, and occlusive vascular changes at young ages (Goodman et al. 1963; Lebwohl et al. 1993).

Although autosomal recessive inheritance is most frequently found in PXE, autosomal dominant segregation has been described as well. These different entities are clinically indistinguishable (Christiano et al. 1992; Lebwohl et al. 1994).

So far, no genes involved in PXE have been identified. The elastin gene, one of the obvious candidate genes, has been excluded as the cause of PXE (Raybould et al. 1994).

Here we report on the localization of a gene for PXE on 16p, in a family from a genetically isolated population in The Netherlands.

RESULTS

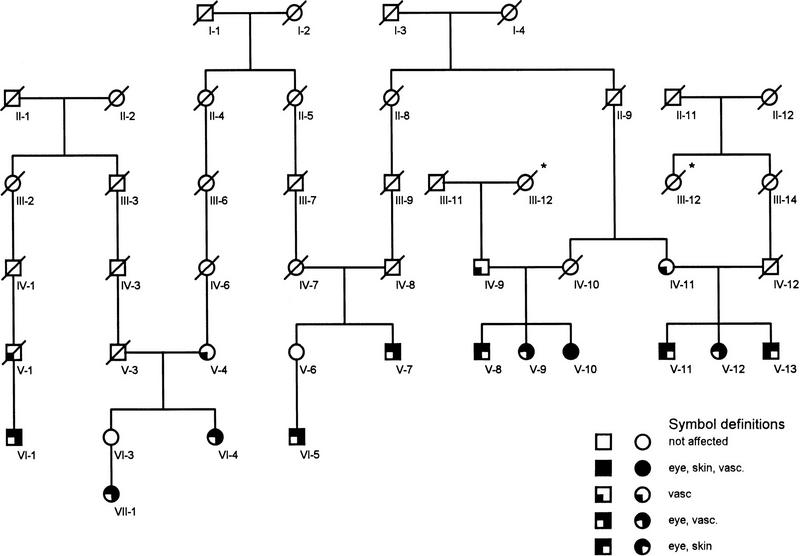

The diagnosis PXE in individuals from this pedigree was based on the results of ophthalmological, dermatological, and cardiovascular examinations. Minimal criteria for the diagnosis of PXE were the presence of ocular signs of PXE (angioid streaks) in combination with at least typical skin lesions or vascular signs indicating PXE. The high level of consanguinity in this population and the absence of transmission of the disease from parent to child indicates autosomal recessive PXE. In view of the variable expression and possible late onset of the disease only affected individuals were included in the genetic analysis. This resulted in the identification of 11 affected individuals, 20–57 years of age, derived from 5 nuclear families that have been linked genealogically. The clinical findings for these individuals are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The PXE pedigree as used in the linkage analysis. To reduce calculation times only minimal links are included. The generation numbers are indicated beneath each individual. The differential diagnoses per affected system—eye, skin, or vascular system (vasc.), are represented by distinct symbols in the pedigree. The asterisk (*) indicates a loop in the pedigree, which was included in the lod score calculation.

An initial genome-wide screen with microsatellite markers evenly spaced every 10–15 cM was conducted on the DNA of three of the affected individuals (VI-1, VI-5, and VI-9). In the course of screening 374 markers, up to 20 genomic regions were found to be homozygous in at least two affected individuals and were tested further in all 11 affecteds. A marker on chromosome 16p (D16S292) was found to be homozygous in two of the three patients. Further analysis with markers from this region resulted in the finding of homozygosity in affected individuals for the markers D16S3079, D16S764, D16S3103, and D16S3017 slightly distal to D16S292. The most likely order of these markers is derived from on-line genetic and physical mapping data, in combination with our own data (not shown): Tel–D16S292–D16S3079–D16S764–(D16S3103/D16S3017)–Cen. Two-point linkage analysis revealed close linkage without recombination between the PXE locus and the marker D16S764, with a maximum lod score of 6.27 (Table 1). Multipoint linkage analysis placed the PXE locus in between the markers D16S3079 and D16S3103.

Table 1.

Results from the Linkage Analyses

| Marker | Recombination fraction | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zmax | Θmax | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.40 | |

| D16S764 | 6.27 | 0.00 | 6.27 | 6.10 | 5.56 | 4.59 | 2.99 | 1.62 | 0.59 |

| D16S3079 | 2.99 | 0.03 | −∞ | 2.78 | 2.95 | 2.60 | 1.71 | 0.91 | 0.32 |

| D16S3103 | 4.70 | 0.03 | 1.71 | 4.55 | 4.60 | 4.09 | 2.83 | 1.61 | 0.60 |

| D16S3017 | 2.93 | 0.03 | −0.29 | 2.70 | 2.91 | 2.60 | 1.76 | 0.96 | 0.35 |

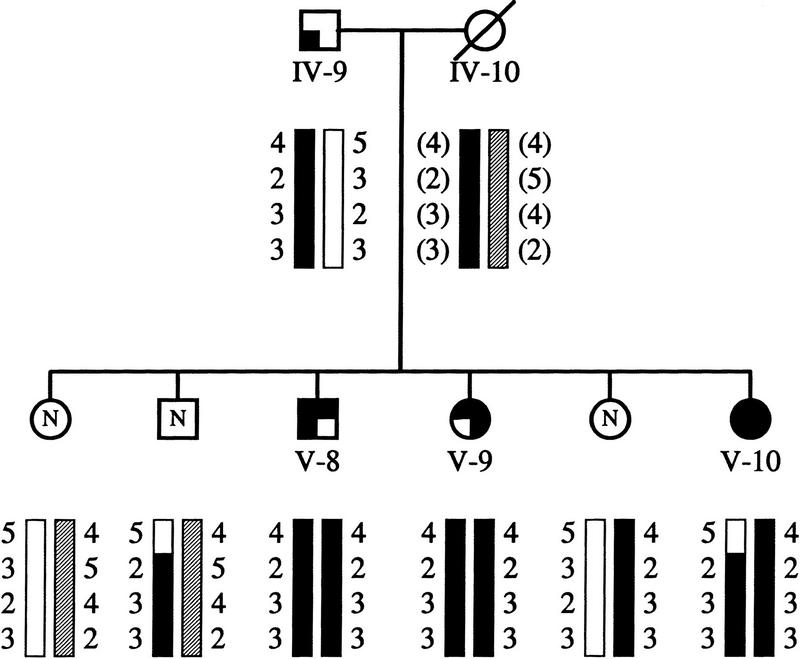

An example of the segregation of the markers in one of the nuclear families is shown in Figure 2. The recombination event between D16S3079 and the PXE locus is observed in individual V-10. Comparison of the haplotypes observed in the affected individuals of the pedigree resulted in the finding of five different haplotypes that show extensive haplotype sharing, as expected for a recessive locus in an isolated population (Table 2). However, the only marker shared among all individuals is allele 2 (112 nucleotides) of D16S764. The latter indicates that ancient recombination events have occurred between the disease locus and both D16S3103 and D16S3017. These results therefore place the PXE locus on chromosome 16p13.1, in a 3- to 4-cM region between D16S3079 and D16S3103/D16S3017.

Figure 2.

One of the nuclear families with PXE. Generation numbers refer to the position of these individuals in the pedigree (Fig. 1). The individuals labeled N were not included in the genetic analysis and are presented here to complete segregation data. The maternal haplotype was inferred. The order of the markers from top to bottom: D16S3079, D16S764, D16S3103, and D16S3017.

Table 2.

The Different Haplotypes Observed in the PXE Pedigree

| Marker | Haplotype | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | |

| D16S3079 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| D16S764 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| D16S3103 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| D16S3017 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

DISCUSSION

Both autosomal recessive and dominant inheritance patterns have been observed previously in families with PXE. This may be attributable to differences in penetrance of the symptoms per system affected. In the pedigree studied here, four out of the nine obvious carriers, from whom sufficient clinical data were available, have been diagnosed with vascular disease. Thus, the disease described here has a genuine recessive character for the skin and eye symptoms while the effect on the vascular system is apparently dominant with a penetrance of 40%–50%. Therefore, both dominant and recessive forms of PXE could possibly be caused by different mutations in the same gene. A similar situation has been found in the rhodopsin gene, in which different mutations cause either dominant or recessive retinitis pigmentosa (Sung et al. 1993; Kumaramnickavel et al. 1994). A detailed clinical study of this pedigree will be published separately (J. Swart and N. Tijmes, in prep.).

Previous linkage analyses in genetic isolates showed that homozygosity mapping is a powerful tool to fine-localize recessive disease genes (Nikali et al. 1995, van Soest et al. 1996). Using this method we mapped the PXE gene between markers D16S3079 and D16S3103, in a region of 3–4 cM on chromosome 16p13.1. All affected individuals were found to be homozygous for allele 2 of D16S764, which has a frequency of only 20% in the Dutch population (A. van Soest, unpubl.).

Physical mapping data in this region include a single linked yeast artificial chromosome (YAC) contig and radiation hybrid mapping data, which have been used to place genes and expressed sequence tags (ESTs) on the physical and genetic map. A number of these expressed sequences may be considered as candidate genes. For instance, the gene for the human multidrug resistance-associated protein (MRP) was mapped in between markers D16S3062 and D16S3103 using the G3 radiation hybrid panel (SHGC). This gene belongs to the superfamily of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) genes (Allikmets et al. 1996). A retina-specific member of this superfamily of specific transporters (ABCR) was recently found to be mutated in individuals with Stargardt macular dystrophy (Allikmets et al. 1997). Another candidate may be the pM5 gene, which maps to the same chromosomal region and codes for a cDNA that shows homology, at the DNA level, to conserved regions of the collagenase gene family (Templeton et al. 1992). Collagen is a major component of the connective tissue and disruption of the collagen metabolism may have a role in PXE (Hausser and Lamprecht 1991; Lebwohl et al. 1993). Besides these candidate genes a number of unidentified transcripts have been mapped to the disease gene region, possibly being parts of the PXE gene. Identification of the gene causing PXE, which is associated with life-shortening vascular disease, may lead to an increase in the understanding of the mechanisms behind the variety of symptoms observed in pseudoxanthoma elasticum and may provide some insight in the etiology of cardiovascular diseases in general.

METHODS

Family Material

The PXE pedigree was ascertained through the register of genetic eye diseases at the Netherlands Ophthalmic Research Institute. Ophthalmological assessment (performed by N. Tijmes and J. Swart) included visual acuity, slit-lamp examination, ophthalmoscopy, and fluorescein angiography. Dermatological examination, in some cases including biopsy, and cardiovascular examination, including electrocardiograph (ECG) were carried out by specialists in these fields. Biopsies were taken from the skin in the neck from all patients included in the linkage analysis. The detailed results of these examinations are described elsewhere (J. Swart and N. Tijmes, in prep.).

DNA Analysis

DNA was isolated from whole blood samples by standard procedures. PCR reactions were carried out essentially as described elsewhere (Weber and May 1989; Bergen et al. 1993). Briefly, reactions were performed in a 12-μl volume in the presence of [α-32P]dCTP. Products were run on polyacrylamide gels and visualized by autoradiography. Details concerning primers used can be found in the Genome Data Base or Genethon database. Statistical analyses were carried out using the computer program LINKAGE package, version 5.04 (Lathrop and Lalouel 1984). To reduce calculation times, the number of alleles was reduced to 3, with equal frequencies. This leads to an underestimation of the evidence for linkage, thus reducing the lod scores. The published frequencies for the alleles associated with the disease locus are 0.05 for D16S3079 (allele 4), 0.2 for D16S3103 (allele 3), and 0.24 for D16S3017 (allele (3). For D16S764 the frequency for allele 2 in the Dutch population is found to be 0.2 (S. van Soest, unpubl.). A gene frequency of 0.0001 was used. Penetrance values for carriers were set to 0.00. The linkage analysis was carried out on the pedigree as shown in Figure 1. For the displayed links in the generations I, II, III and IV-1, IV-3, and IV-6 no phenotypic information was included. All living family members as displayed in Figure 1 were included in the DNA analysis.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the family members for their willingness to cooperate in this study. We thank Dr. Martijn Breuning for helpful advice. This study was supported by the Dutch Society for Prevention of Blindness.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL A.Bergen@ioi.knaw.nl; FAX (+31)-20-6916521.

REFERENCES

- Allikmets R, Gerrard B, Hutchinson A, Dean M. Characterization of the human ABC superfamily: Isolation and mapping of 21 new genes using the expressed sequence tags database. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;10:1649–1655. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.10.1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allikmets R, Singh N, Sun H, Shroyer NF, Hutchinson A, Chidambaram A, Gerrard B, Baird L, Stauffer D, Peiffer A, Rattner A, Smallwood P, Li Y, Anderson KL, Lewis RA, Nathans J, Leppert M, Dean M, Lupski JR. A photoreceptor cell-specific ATP-binding transporter gene (ABCR) is mutated in recessive Stargardt macular dystrophy. Nature Genet. 1997;15:236–247. doi: 10.1038/ng0397-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergen AAB, Wapenaar MC, Schuurman EJM, Diergaarde PJ, Lerach H, Monaco AP, Bakker E, Bleeker-Wagemakers EM, van Ommen GJB. Detection of a new submicroscopic Norrie disease deletion interval with a novel DNA probe isolated by differential Alu PCR fingerprint cloning. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1993;62:231–235. doi: 10.1159/000133484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bressler NM, Bressler SB, Gragoudas ES. Clinical characteristics of choroidal neovascular membrane. Arch Ophthalmol. 1987;105:209–213. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1987.01060020063030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiano AM, Lebwohl MB, Boyd CD, Uitto J. Workshop on pseudoxanthoma elasticum: Molecular biology and pathology of the elastic fibers. Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, June 10, 1992. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;5:660–663. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12668156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman RM, Smith EW, Paton D, Bergman RA, Siegel ChL, Ottesen OE, Shelly WM, Pusch AL, McKusick VA. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: A clinical and histopathological study. Medicine. 1963;42:297–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausser I, Anton-Lamprecht I. Early preclinical diagnosis of dominant pseudoxanthoma elasticum by specific ultrastructural changes of dermal elastic and collagen tissue in a family at risk. Hum Genet. 1991;87:693–700. doi: 10.1007/BF00201728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumaramanickavel G, Maw M, Denton MJ, John S, Srisailapathy Srikumari CR, Orth U, Oehlmann R, Gal A. Missense rhodopsin mutation in a family with recessive RP. Nature Genet. 1994;8:10. doi: 10.1038/ng0994-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lathrop GM, Lalouel JM. Easy calculations of lod scores and genetic risks on small computers. Am J Hum Genet. 1984;36:460–465. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebwohl M, Schwartz E, Lemlich G, Lovelace O, Shaikh-Bahai F, Fleischmajer R. Abnormalities of connective tissue components in lesional and non-lesional tissue of patients with pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Arch Dermatol Res. 1993;285:121–126. doi: 10.1007/BF01112912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebwohl M, Neldner K, Pope FM, De Paepe A, Christiano AM, Boyd CD, Uitto J, McKusick VA. Classification of pseudoxanthoma elasticum: Report of a consensus conference. J Am Acad Dermat. 1994;30:103–107. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(08)81894-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour AM, Shields JA, Annesley WH, Jr, El-Baba F, Tasman W, Tomer TL. Macular degeneration in angioid streaks. Ophthalmologica. 1988;197:36–41. doi: 10.1159/000309915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neldner KH. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Clin Dermatol. 1988a;6:1–159. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(88)90003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Int J Dermatol. 1988b;27:98–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1988.tb01280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikali K, Suomalainen A, Terwilliger J, Koskinen T, Weissenbach J, Peltonen L. Random search for shared chromosomal regions in four affected individuals: The assignment of a new hereditary ataxia locus. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;56:1088–1095. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raybould MC, Birley AJ, Moss C, Hulten M, McKeown CM. Exclusion of an elastin gene (ELN) mutation as the cause of pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE) in one family. Clin Genet. 1994;45:48–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1994.tb03990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung C-H, Davenport CM, Nathans J. Rhodopsin mutations responsible for autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. J Biol Chem. 1993;35:26645–26649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Templeton NS, Rodgers LA, Levy AT, Ting KL, Krutzsch HC, Liotta LA, Stetler-Stevenson WG. Cloning and characterization of a novel human cDNA that has a DNA similarity to the conserved region of the collagenase gene family. Genomics. 1992;12:175–176. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(92)90425-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Soest S, te Nijenhuis S, van den Born LI, Bleeker-Wagemakers EM, Sharp E, Sandkuijl LA, Westerveld A, Bergen AAB. Fine mapping of the autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa locus (RP12) on chromosome 1q; exclusion of the phosducin gene (PDC) Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1996;73:81–85. doi: 10.1159/000134313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber JL, May PE. Abundant class of human DNA polymorphisms which can be typed using the polymerase chain reaction. Am J Hum Genet. 1989;44:388–396. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]