Abstract

We report here the isolation and genomic organization of the orthologous mouse Duffy gene, named Dfy. It is a single copy gene located in chromosome 1 in a region homologous to the human Duffy gene (FY). Sequence analyses indicate that Dfy consists of two exons: exon 1 of 55 nucleotides, which encodes 7 amino acid residues; and exon 2 of 1038 nucleotides, which encodes 327 residues. The single intron consists of 462 nucleotides. The 5′-end promoter region contains motifs involved in vertebrate development in addition to potential binding sites of factors for globin transcription. The open reading frame (ORF) shows 60% homology with the human Duffy protein. However, mouse erythrocytes are serologically Duffy-negative and mouse erythrocyte membrane proteins do not cross-react with two Duffy-specific rabbit polyclonal antibodies. The deduced protein predicts a Mr of 36,692 and carries three potential N-glycosylation sites to asparagine residues. Hydropathy analysis predicts an exocellular amino-terminal domain of 57 residues, seven transmembrane α-helices, and an endocellular carboxy-terminal domain of 29 residues. In bone marrow and spleen, Dfy expresses a major 1.4-kb and a minor 1.8-kb mRNA. Contrary to humans, Dfy is expressed in liver, synthesizing a 1.4-kb mRNA, and is repressed in kidney. Dfy is highly expressed in mouse brain and produces a major 8.5-kb and a minor 10.2-kb mRNA. The human erythroleukemia K562 cells, transfected with cDNA encoding the mouse Duffy-like protein and mouse erythrocytes, have the same chemokine binding profiles indicating that they contain the same protein.

[The sequence data described in this paper have been submitted to GenBank under accession nos. AF016584 and AF016697.]

A glycoprotein (gp-Fy) of 337 amino acids, which is present in the membrane of erythrocytes of Duffy-positive individuals, carries the antigenicity of the Duffy blood group system (Marsh 1975; Tang et al. 1988). Two codominant alleles (FY*A and FY*B) at the 1q22 → q23 chromosomal locus encode the Fya/Fyb alloantigens (Donahue et al. 1968; Collins et al. 1992; Mathew et al. 1994). A single G → A nucleotide substitution at position 306 of FY produces a glycine → aspartic acid substitution at residue 43 of gp-Fy and determines the immunogenic difference between gp-Fya and gp-Fyb (Chaudhuri et al. 1995; Mallinson et al. 1995; Tournamille et al. 1995b; Iwamoto et al. 1996).

The significance of the Duffy system stems from its role as the receptor for the human malarial parasite Plasmodium vivax and simian malarial parasite Plasmodium knowlesi (Miller et al. 1975, 1976) and as a new class of chemokine receptor for several proinflammatory cytokines (Darbonne et al. 1991; Hadley et al. 1991, 1994; Chaudhuri et al. 1994; Horuk 1994; Horuk et al. 1994; Neote et al. 1994). Binding studies of chemokines to human erythroleukemia K562 and human embryonic kidney 293 cell lines, transfected with cDNA encoding for the cloned gp-Fy, have shown that gp-Fy and the human erythrocyte chemokine receptor are the same protein (Chaudhuri et al. 1994; Neote et al. 1994).

Most African and American blacks have red cells that lack Fya and Fyb alloantigens. This class of erythrocytes resists invasion by P. vivax and P. knowlesi parasites (Miller et al. 1975, 1976). These individuals carry a FY*B allele that is bone marrow silent but active in nonerythroid tissues (Chaudhuri et al. 1995; Peiper et al. 1995). In the promoter region of this FY*B allele there is a T → C substitution that disrupts a binding site for GATA I erythroid transcription factor (Tournamille et al. 1995a). However, the mutation does not affect the expression of the Duffy gene in other cell types (Chaudhuri et al. 1995, 1997; Peiper et al. 1995).

Serological studies in nonhuman primates have uncovered significant information about antigenic and genetic relationships of Duffy proteins (McGinnis and Miller 1977; Palatnik and Rowe 1984). Moreover, the study of FY structure in nonhuman primates yielded information about the homology and ancestry of Duffy sequences. For example, Duffy gene structure in chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes), rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta), squirrel monkey (Saimiri sciureus), and aotus monkey (Aotus trivirgatus) provides evidence that the first human Duffy allele was probably FY*B and a point mutation at nucleotide 306 produced FY*A (Chaudhuri et al. 1995). Thus, FY*A has not been found in nonhuman primates, and it may not exist. Although horse and sheep erythrocytes do not react with any human Duffy antisera (Palatnik and Rowe 1984), it is conceivable that they express a Duffy-like gp-Fy that is serologically Duffy-negative. Concurrently, a homologous FY, producing a Duffy-like gp-Fy that does not react with any human Duffy antisera should exist in mouse. Here, we report the identification and characterization of an orthologous mouse Dfy, which produces a protein that has 60% homology to the human equivalent but does not react with any human Duffy antisera, including rabbit polyclonal antibodies to denatured human gp-Fy. The discovery of this gene in mouse provides a tool to gain further insights into the role of the human Duffy gene FY.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Sequence Analysis of Dfy and Bone Marrow cDNA

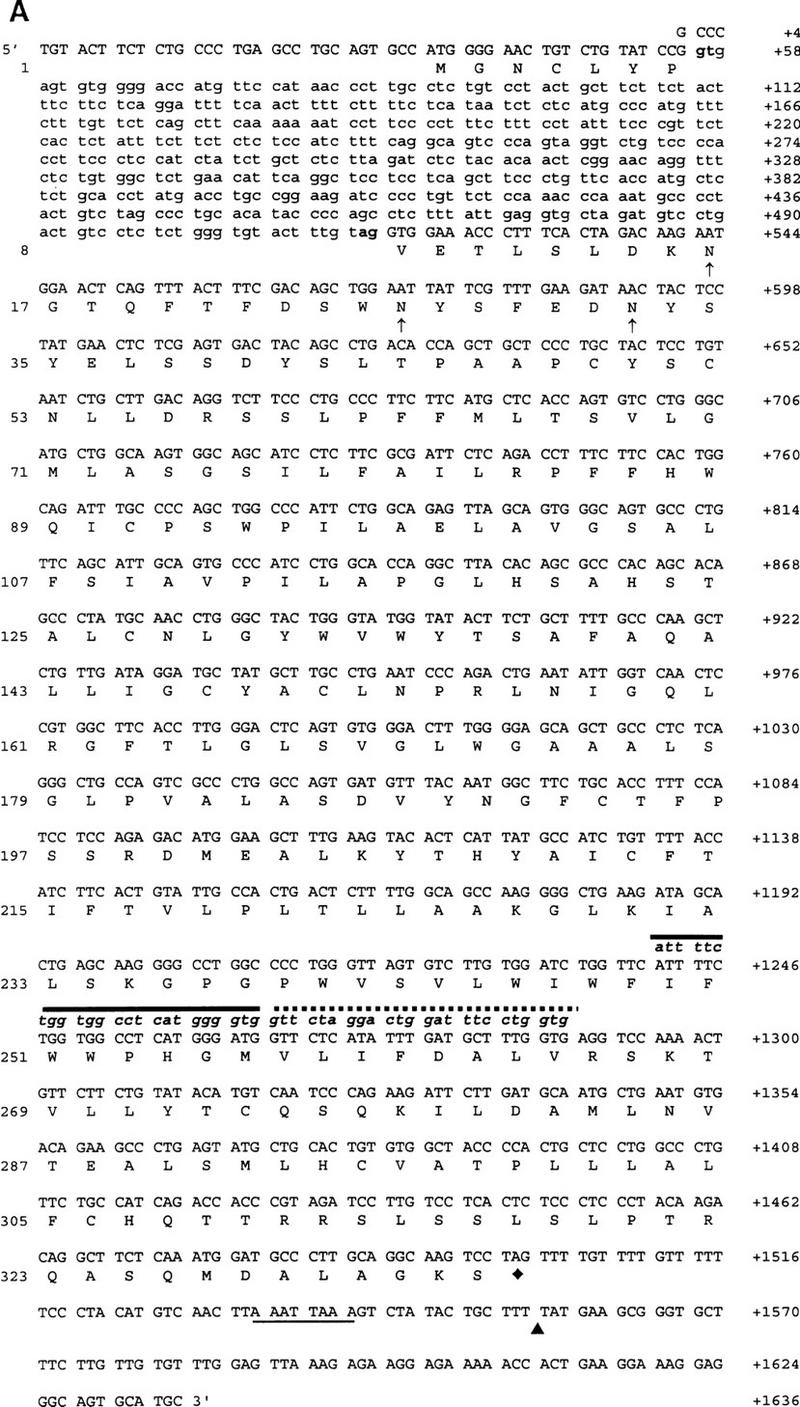

Nucleotide analysis of Dfy and bone marrow cDNA indicated that the structure of Dfy consists of two exons and a single intron (Fig. 1A). Exon 1, of 55 nucleotides, encoded seven amino acid residues that were initiated with a methionine. The initiation codon of exon 1 was embedded within a sequence context most frequently associated with mammalian translation initiation (Kozak 1989). This short exon was connected at nucleotide 518 (in-frame) with the long exon 2 that contained 1038 nucleotides, encoding 327 residues. The single intron of 462 nucleotides contained the conserved boundary sequences (gt–ag) of the splice site (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

(A) Genomic DNA and cDNA structure of Dfy and deduced amino acid sequence of mouse Duffy-like protein. Amino acid residues are numbered on left; nucleotide positions are numbered on right. The exon and intron sequences are shown in uppercase and lowercase, respectively. The consensus sequence at the intron splice site is indicated in boldface letters. The three potential carbohydrate-binding sites to asparagine residues are shown in up arrows. The primers’ nucleotide sequences are shown in lowercase, italic, and boldface letters. P2 nucleotides are shown by a solid line and P1 by a dotted line. The underline is the polyadenylation signal. (▴) The polyadenylation site; (♦) the stop codon. (B) 5′-end promoter flanking sequence of Dfy. (▿) The position (+1) of the major transcription initiation site. Consensus sequences for the transcription factor binding sites are boxed, and the name of the corresponding factors are shown. The arrows indicate consensus sequences in sense strand (right) and antisense strand (left).

Primer extension with 5′-end-labeled oligonucleotides, complementary to the 5′-end coding sequences of the bone marrow mRNA was used to define the 5′ end of the mRNA. Although several distinct bands were observed, the one located at nucleotide position 34, upstream from the initiation codon, was the most prominent (not shown). The same major start site was shown for the spliced form of human mRNA (Iwamoto et al. 1996). The significance of minor transcription initiation sites generated by alternative promoters remains to be clarified (Kopito et al. 1987; Iwamoto et al. 1996).

Upstream sequence analysis of the major transcription initiation site revealed a TATA box at position −96 bp (Fig. 1B). Its location suggests that it may be a nonfunctional promoter, and by this criterion Dfy is a TATA-less gene like FY (Saito and Stark 1986; Tournamille et al. 1995a; Zhuchenko et al. 1996). The mouse Dfy also lacks a CAAT motif and unlike most eukaryotic genes, including the human FY gene, which lack TATA or CAAT sequences, does not have pyrimidine-rich or (G + C)-rich sequences upstream from the transcription initiation site (Kopito et al. 1987; Tournamille et al. 1995a; Zhuchenko et al. 1996).

Further sequence analysis of the 5′-end promoter region has revealed potential binding sites of factors for globin transcription. There is a GATA motif at position −33 followed by two upstream CACCC motifs; one at position −83 and the other at position −142 (Fig. 1B). These widely studied cis-acting sites are implicated in the coordinate regulation of α- and β-globin production (Ren et al. 1996). Another potential cis-acting element in this promoter region is the AP-2 motif at position −45. A second, but distant AP-2 motif, at position −319, is also present. This motif is a potential binding site for AP-2 factor, which is a regulator during vertebrate development (Mitchell et al. 1991).

Additional sequence motifs possibly involved in the expression of transcription of Dfy are the overlapping sequences of PEA-3/ETS at position −191 and upstream, the cAMP response element (CRE) at position −393 (Faisst and Meyer 1992; Zhuchenko et al. 1996). It has been shown that cAMP response element-binding (CREB) protein is expressed and activated by phosphorylation in human heart (Muller et al. 1995), whereas polyomavirus enhancer activator 3 (PEA-3) is a member of the ETS oncogene family that is differentially expressed in mouse embryonic cells (Macleod et al. 1992; Xin et al. 1992). It is interesting that the 5′-end promoter region of Dfy has revealed several potential binding sites for transcription factors associated with vertebrate morphogenesis. Finally, at the 3′-end flanking sequence, the consensus poly(A) addition signal AATTAAA was identified (Fig. 1A).

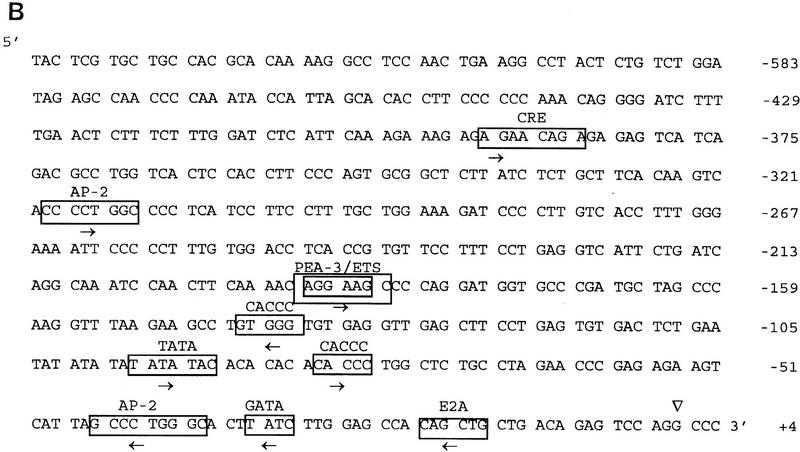

The size of human and mouse spliced mRNAs are the same (Iwamoto et al. 1996; A. Chaudhuri, F. Fang, V. Zbrzezna, and A.O. Pogo, unpubl.). Exon 1 and exon 2 in both mRNAs contain the same number of nucleotides, 55 and 1038, respectively. However, the intron in mouse contains 462 bp and in human, 479 bp (Iwamoto et al. 1996; A. Chaudhuri, F. Fang, V. Zbrzezna, and A.O. Pogo, unpubl.) (Fig. 1A). Although human and mouse exon 1 codified for the same number of residues, only the first five residues were identical (Fig. 2). The comparison of both exons’ open reading frames (ORFs) in human and mouse spliced mRNA showed 60% homology (Fig. 2). The predicted mouse Duffy-like protein was a slightly basic protein of isolelectric point 7.37, having a molecular mass slightly higher (Mr 36,692) than the human gp-Fy (Mr 35,733). The presence of two trypsin cleavage sites at the amino terminus is another feature that differentiated the mouse from the human protein.

Figure 2.

Alignment of the amino acid sequences of the proteins codified by mouse and human spliced mRNAs. Amino acid residues are at right. Horizontal lines indicate seven transmembrane spanning α-helices. Vertical lines indicate identical residues. Arrows and ♦ indicate invariant cysteines and prolines, respectively.

Mouse Duffy-like protein carries three potential canonical sequences at the amino terminus for N-glycosylation to asparagine residues (Marshall 1972) (Fig. 1A). The first asparagine is located at the same distance from the amino terminus, position 16, in both proteins. The second asparagine is located at position 26 in mice and 27 in humans, and the third asparagine is located at position 32 in mice and 33 in humans (Fig. 1A). The presence of aspartic acid, however, restricts the glycosylation of the third asparagine in humans (Marshall 1972). Although Duffy-like protein in mice may contain more carbohydrates than humans, the similarity in the number and topology of the glycosylation sites may imply a conserved function.

Predictions of transmembrane helices from sequence data by use of the hydropathy map of Engelman et al. (1986) and a scanning window of 20 residues show seven well-defined transmembrane α-helices, a hydrophilic domain of 57 residues at the amino terminus, and a hydrophilic domain of 29 residues at the carboxyl terminus (not shown). Mouse Duffy-like protein exhibits better defined transmembrane domains than human protein (Chaudhuri et al. 1993). The same hydrophobicity scale in human Duffy protein predicted nine α-helices. Thus, the fourth and sixth transmembrane domains in humans have too many hydrophobic residues to accommodate a single pass to the membrane width (Chaudhuri et al. 1993). Nevertheless, considering that Duffy protein is the human erythrocyte chemokine receptor and that all chemokine receptors have seven transmembrane spanning regions, seven α-helices may be the real transmembrane structure of this protein (Neote et al. 1993, 1994). In comparison to the chemokine receptors, the loops of the mouse protein, like the human gp-Fy, are very short, and the DRYLAIVHA motif at the end of the third transmembrane domain is absent (Fig. 2). This motif is unique to all members of the chemokine receptor family (Murphy 1994). The structural features that the mouse Duffy-like protein shares with all chemokine receptors are (1) five prolines in the transmembrane domains 2, 4, 5, 6, and 7; (2) a cysteine at position 49 in the amino-terminal domain; and (3) cysteines at positions 127, 193, and 274 in the three exocellular loops (Fig. 2). These residues are preserved in the corresponding positions of all the leukocytes and viral chemokine receptors (Murphy 1994). At the amino-terminal domain the cysteine at position 49 can establish a disulfide bond with the cysteine at position 274 in the third exocellular loop, and in the first exocellular loop the cysteine at position 127 can establish a disulfide bond with the cysteine at position 190 in the second exocellular loop (Fig. 2).

The charge-difference rule proposed by Hartman et al. (1989), predicting that the amino terminus is on the exocellular side of the membrane, is validated by the finding of three potential N-glycosylation sites on this domain. The topological predictions of helices, hydrophilic connecting segments, and location of the carboxy-terminal fragments should be substantiated by direct biochemical and immunochemical analysis.

Mouse erythrocytes were not agglutinated by human Duffy antisera (not shown). Furthermore, rabbit polyclonal antibodies that are Duffy-specific, and react with either the carbohydrate moiety or the protein moiety of denatured human Duffy protein do not react with mouse ghost proteins (not shown). Consequently, the mouse erythrocytes carry a Duffy-like protein that has 60% amino acid sequence homology with gp-Fy and its membrane topology is similar to gp-Fy, but they are serologically Duffy-negative.

RNA Blot Analysis

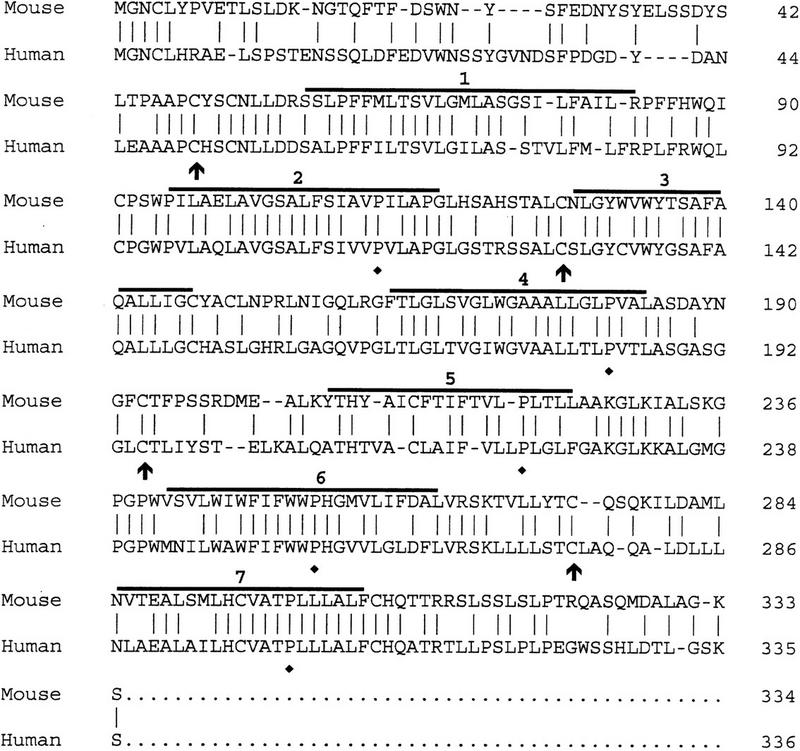

On RNA blot analysis, the exon 2 probe detected a major ∼1.4-kb and a minor ∼1.8-kb mRNA in bone marrow and spleen. In brain, the probe detected a major 8.5-kb and two minor mRNAs of 10.2 and ∼3.0 kb (Fig. 3). Also, the same probe hybridized with a 1.4-kb mRNA in adult liver but failed to hybridize with Duffy-like mRNA in kidney and lung (Fig. 3). [In lung, a faint band of 1.4-kb mRNA was observed after overexposure and a small amount of mRNA was detected by RT–PCR (not shown).] In heart and skeletal muscles, a small quantity of a 8.5- and a 1.4-kb mRNA was observed (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

RNA blot analysis of mRNA from mouse tissues probed with exon 2 of Dfy. (Lane 1) 2 μg of bone marrow mRNA; (lane 2) 5 μg of spleen mRNA; (lane 3) 5 μg of liver mRNA; (lane 4) 5 μg of lung mRNA; (lane 5) 10 μg of kidney mRNA; (lane 6) 10 μg of heart mRNA; (lane 7) 5 μg of skeletal muscle mRNA; (lane 8) 1 μg of brain mRNA. Actin probe was used to test the integrity of the mRNA fraction and to determine the relative abundance of poly(A)+ RNA. RNAs were resolved on a 1.5% denaturing agarose gel hybridized and autoradiographed for 5 days. The relative amount of mRNA was determined with the Eagle Eye II Still Video System (Stratagene). The Duffy-like mRNA/actin mRNA ratios were as follows: (lane 1) 1.80; (lane 2) 2.30; (lane 3) 0.78; (lane 4) −; (lane 5) −; (lane 6) 0.09; (lane 7) 0.09; (lane 8) 10.72.

The pattern of tissue expression of Dfy in mice is different from that of the orthologous gene in humans. Unlike humans, mouse Dfy is active in adult liver, which is not an erythropoietic organ, and is inactive in kidney. The most striking difference is in brain, which is the major producer of mRNAs related to Duffy (Fig. 3). In mice, the relative abundance of the 8.5-kb mRNA is five times greater in brain than the 1.4-kb mRNA in bone marrow (Fig. 3). It seems that protein encoded by the 8.5-kb mRNA is a significant component of mouse brain.

Southern Blot Analysis and Chromosomal Mapping

On Southern blot analysis, the exon 2 probe detected a single band of 7.0 kb in BamHI and EcoRI, a single band of 8.5 kb in XbaI, a single band of 1.8 kb in PstI, and two bands of 2.0 and 0.09-kb in HindIII-digested mouse genomic DNA (not shown). (Two bands in the HindIII-digested genomic DNA are attributable to the presence of a HindIII restriction site in exon 2.) As in humans, there is a single copy of Duffy-like gene in mice (Chaudhuri et al. 1993).

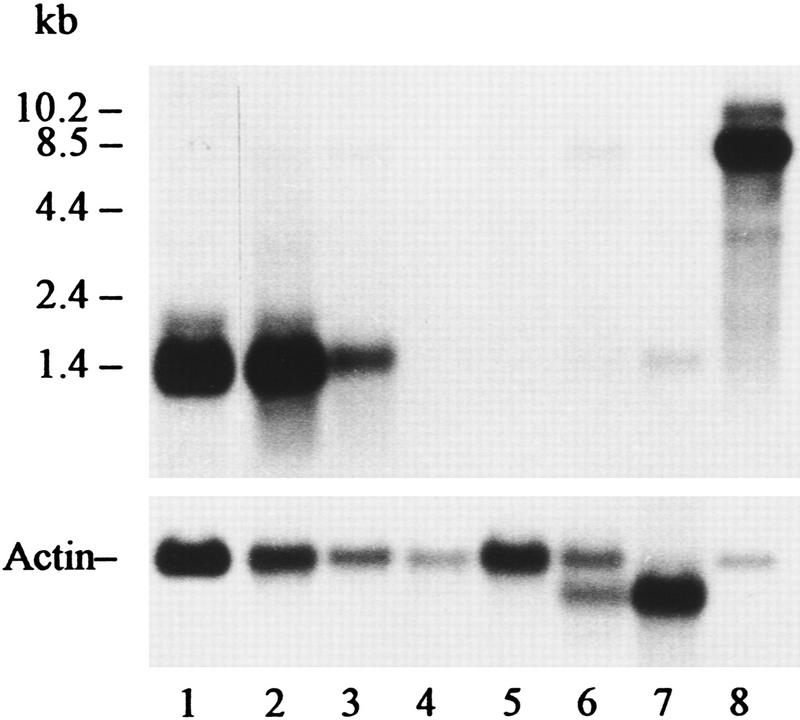

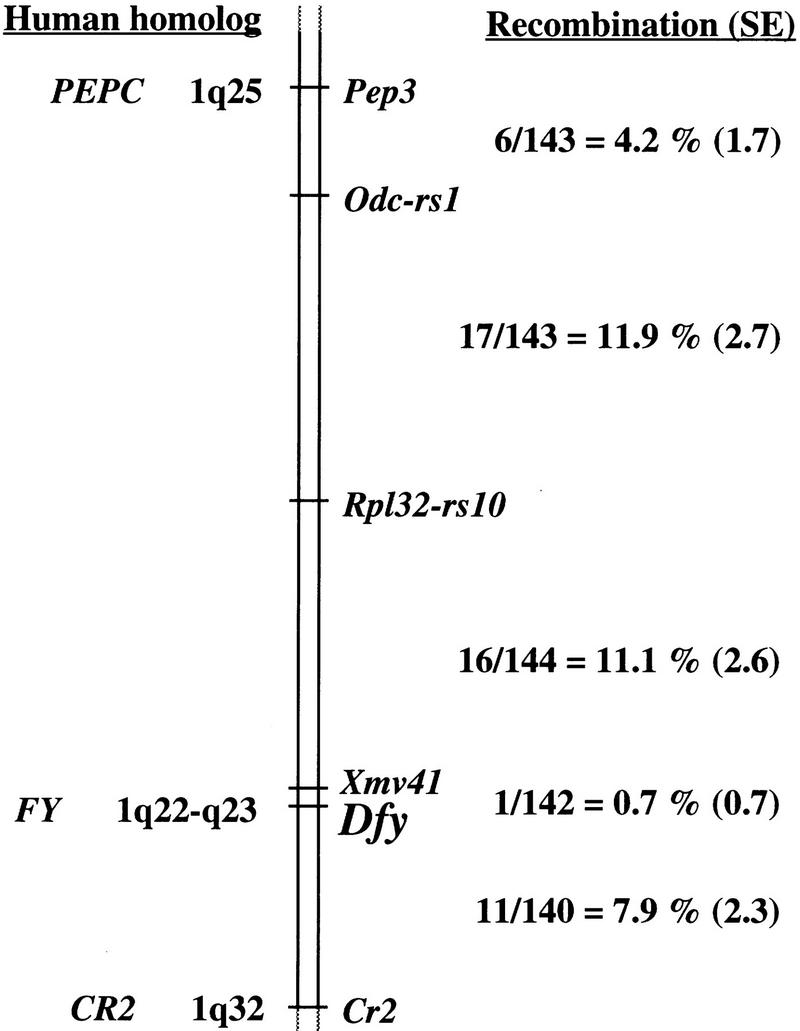

A single band was also observed with TaqI-digested mouse genomic DNA (not shown). The size of TaqI-hybridizing DNA fragments differed between the parental inbred mouse strains, C57BL/6J (2.4 kb) and SPRET/Ei (4.8 kb), used to produce the MMR–BSS interspecific backcross. Backcross progeny genotypes for Dfy were assigned according to the absence or presence of the diagnostic C57BL/6J-derived 2.4-kb fragment inherited from the F1 hybrid parent of the backcross. Segregation of Dfy among the backcross progenies was then compared with the segregation of previously typed and mapped marker loci distributed throughout the genome. Genetic linkage was detected with markers on mouse Chromosome (Chr) 1. Haplotype analysis, minimizing multiple crossover events, gave the gene order shown in Figure 4, with Dfy positioned between Xmv41 and Cr2. The Mouse Genome Database (MGD 1966) has assigned Xmv41 to position 93 and Cr2 to position 107 on the composite map of mouse Chr 1. Thus, according to our mapping results, Dfy is located ∼94 cM distal to the centromere of the composite map of mouse Chr 1, which places it in a region of conserved synteny with Chr 1q21–1q23 (MGD 1996), consistent with the location for the human FY (Donahue et al. 1968; Mathew et al. 1994).

Figure 4.

Location of Dfy on mouse chromosome 1. The genetic map was derived from segregation analysis of 144 interspecific backcross progeny. The number of observed recombinant chromosomes over the total number of analyzed chromosomes was used to estimate the recombination frequency between adjacent loci. These interlocus recombination estimates are shown to the right of the chromosome along with their associated standard errors (shown in parentheses). Map locations for known human homologs are shown at left.

Expression of Mouse Duffy-like Protein in K562 Cells

We and others have shown that gp-Fy and the human erythrocyte chemokine receptor are the same protein (Chaudhuri et al. 1994; Neote et al. 1994). Recently, it has been shown that mouse erythrocytes bind human and murine chemokines (Szabo et al. 1995). As with the human erythrocytes, C–C and C–X–C chemokines appear to compete for binding to a single site on the surface of the mouse red cells (Szabo et al. 1995). This indicates that mouse erythrocytes also have a promiscuous chemokine receptor. It is important to determine whether the cloned mouse Duffy-like protein possesses the same binding characteristics as the mouse erythrocyte chemokine receptor.

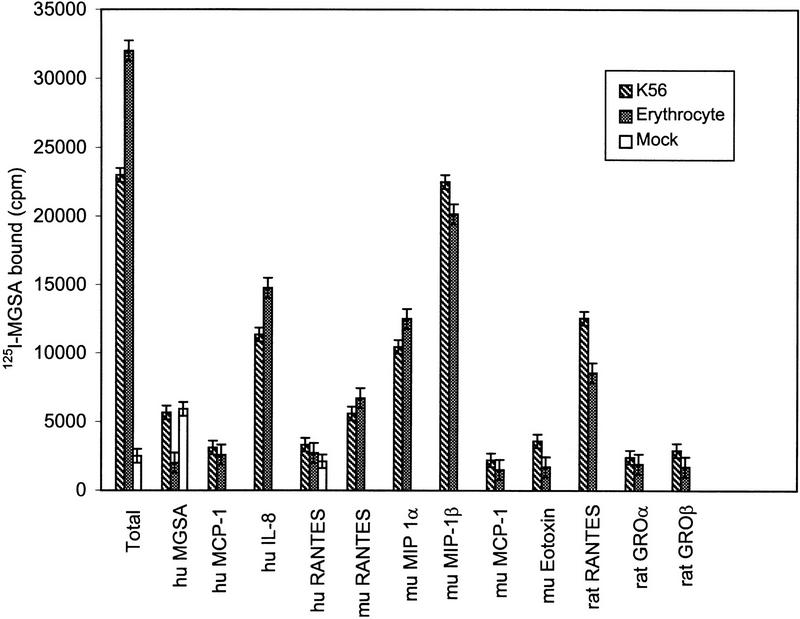

A full-length mouse bone marrow mRNA coding for the Duffy-like protein was amplified by RT–PCR. The amplified cDNA was inserted into the pREP4 expression vector and transfected into K562 cells (see Methods). Stable K562-transfected cells expressing the mouse protein and mock-transfected cells were used for receptor binding studies with 125I-labeled melanoma growth-stimulation activity (MGSA). Transfected K562 cells with the recombinant Duffy-like protein and mouse erythrocytes bound radiolabeled MGSA (Fig. 5). This binding was specific because the addition of 250 nm of unlabeled MGSA significantly reduced the binding to K562 cells and erythrocytes (Fig. 5). In contrast, mock-transfected K562 cells did not show any specific 125I-labeled MGSA binding. Furthermore, 125I-labeled MGSA binding to mouse erythrocytes and transfected K562 cells was displaced by the addition of several human, murine, and rat chemokines, including monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1), interleukin-8 (IL-8), RANTES (regulated upon activation, normal T expressed and secreted), Eotaxin, GROα, and GROβ. The addition of unlabeled MGSA to mock-transfected K562 cells caused a slight increase in the amount of unspecific binding of radiolabeled MGSA (Fig. 5). This is most likely caused by chemokine aggregation at high ligand concentration (Graham et al. 1994). Like the human erythrocyte, chemokine receptor macrophage inflammatory protein 1 α (MIP-1α) partially displaced the binding of 125I-labeled MGSA and MIP-1β slightly inhibited the binding of 125I-labeled MGSA (Chaudhuri et al. 1994).

Figure 5.

Inhibition of 125I-labeled MGSA binding to K562 cells stably expressing the mouse Duffy-like protein and mouse erythrocytes. K562 cells and mouse erythrocytes were incubated for 30 min at 37°C with 125I-labeled MGSA (0.5 nm) in the absence or presence of 0.25 μm of unlabeled MGSA, MCP-1, IL-8, RANTES, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, Eotaxin, GROα, and GROβ. The binding reactions were stopped as described (Neote et al. 1993; Chaudhuri et al. 1994). The data are expressed as cpm of 125I-labeled MGSA bound (per 106 cells) for K562 cells and (per 107 cells) for mouse erythrocytes. Abbreviations for human and murine chemokines are hu and mu, respectively.

To compare the binding affinity of 125I-labeled MGSA for the mouse Duffy-like protein and the transfected K562 cells, receptor competition curves were generated over a wide range of unlabeled ligands. The binding data were analyzed by the LIGAND (Munson and Rodbard 1980) computer program to determine displacement binding constants (KD) and number of sites. For GROα, GROβ, RANTES, Eotaxin, and MCP-1, the data yielded linear plots (Scatchard analysis) consistent with a single class of sites with KD values of 8.49 (±0.5), 4.52 (±0.65), 24.99 (±2.1), 13.9 (±0.72), and 4.14 (±0.50) nm, respectively, for erythrocytes and 10.3 (±0.58), 6.46 (±0.88), 12.7 (±2.05), 20.43 (±1.68), and 4.74 (±0.53) nm (±), respectively, for K562 cells. The relative affinities of erythrocytes and K562 cells for the ligands were strikingly similar. The average protein densities for mouse erythrocytes were 22,000 (9,000–45,000) sites per cell and 286,000 (125,000–547,000) sites per cell for K562 cells. These values are similar to those obtained for the human erythrocytes and transfected K562 cells with Duffy antigen cDNA (Neote et al. 1993; Chaudhuri et al. 1994).

Based on these data, the mouse erythrocyte Duffy-like protein can bind chemokines equivalent to those that the human Duffy antigen binds, indicating that both proteins have similar chemokine-binding characteristics. Moreover, the same class of chemokines competes for MGSA in mouse erythrocytes and in transfected K562 cells. The data strongly suggest that the cloned mouse Duffy-like protein and the mouse erythrocyte chemokine receptor is the same molecule.

Conclusion

In the present study, a mouse gene orthologous to the human FY has been identified, and the DNA, cDNA, and amino acid sequence structures have been resolved. The mouse equivalent protein is encoded by a spliced mRNA that consists of a small and a large exon and is very similar to the human spliced mRNA. At this time, a nonspliced mouse Dfy mRNA has not been found. Dfy maps in a region of conserved synteny with human FY. The pattern of Dfy transcription in nonerythroid tissues, however, is different from the orthologous human FY. Dfy mRNA is primarily produced in bone marrow, brain, liver, and spleen and, unlike humans, is not found in kidney. Moreover, there is little Dfy mRNA in the heart, lung, and skeletal muscles of mice. A remarkable feature in mice is the abundance of brain mRNA. As in human brain, mouse brain produces essentially high molecular weight mRNA, which supports the idea that the Duffy gene is a portion of a larger gene. Now the challenge is to identify the product of this larger gene in brain.

The topological structure, transmembrane α-helices, and amino- and carboxy-terminal domains of mouse protein are the same as human gp-Fy and chemokine receptors. Sequencing of Dfy DNA revealed the genomic organization including the intron/exon boundary and the 5′-flanking promoter region. This region is rich in potential transcription factor binding sites, including AP-2, which has a role in transcription regulation during morphogenetic processes. We have presented evidence that the cloned Duffy-like protein is the same molecule as the mouse erythrocyte chemokine receptor because it has the same binding characteristics as the human erythrocyte chemokine receptor. Both proteins bind radiolabeled MGSA, and this binding is displaced by the same spectrum of unlabeled chemokines.

This study provides the necessary information to mutate the Duffy gene and gain insight into the function of the Duffy antigen. Thus, the data presented here give the foundation for a functional assessment of this peculiar chemokine receptor including its roles in erythrocytes, endothelial cells, epithelial cells, and brain cells.

METHODS

Animals

The B6CBA/F1 strain of mouse was used for the cloning of Dfy and the C57BL/6J and SPRET/Ei strains were used for chromosomal mapping. All animals were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME).

Cell Culture

The human erythroleukemia K562 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal calf serum. Transfected K562 cells were maintained in the same medium containing 200 μg/ml of hygromycin (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN). For binding assays, the cells were collected, washed three times with RPMI 1640, and suspended in binding buffer (RPMI 1640 containing 15% bovine serum albumin, 20 mm HEPES at pH 7.4). Cell viability was assessed by trypan blue exclusion and the cell number was determined in a cell hemacytometer.

Serological Determinations

Mouse erythrocyte hemagglutination tests were performed with human Duffy antisera according to standard procedures to determine Duffy antigenic domains in human erythrocytes.

RNA (Northern) and DNA (Southern) Blot Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from bone marrow cells and tissues with the TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Poly(A)+ RNAs were purified with the MessageMaker mRNA isolation system (Life Technologies) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Poly(A)+ RNAs were run in a formaldehyde/agarose gel and transferred onto a Hybond-N+ nylon membrane (Amersham Life Science, Arlington Heights, IL) and hybridized as explained (Chaudhuri et al. 1993).

DNA was extracted from kidneys as explained (Frederick et al. 1994). All restriction enzyme digestions were performed according to the supplier’s instructions (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA). The digested DNA was size-fractionated on 0.8% agarose gel, blotted, and hybridized as explained (Chaudhuri et al. 1993).

Primer Design, Cloning, and Sequencing Dfy

The cassette ligation-mediated PCR method was used for identifying and sequencing Dfy (Isegawa et al. 1992). Two contiguous antisense primers were designed. P1 (5′-CACCAGGAAATCCAGTCCTAGAAC-3′) and P2 (5′-CACCCCATGAGGCCACCAGAAAAT-3′) were from nucleotide 956–979 and nucleotide 932–955 of human FY, respectively (Chaudhuri et al. 1993) (Fig. 1A). The primers were designed from a region of the human FY, which has maximal homology with the nonhuman primate Duffy gene (Chaudhuri et al. 1995). Of the two primers constructed, only P2 showed the highest homology (Fig. 1A).

Mouse genomic DNA was digested to completion with PstI and ligated with PstI cassettes (TaKaRa Biomedicals, Pan Vera Corp., Madison, WI). Two sequential PCR amplifications were performed: one using P1 primer and cassette primer C1 and the other using P2 primer and cassette primer C2. The amplified products were hybridized at moderated stringency with the human Duffy cDNA probe (Chaudhuri et al. 1993). A 1.2-kb fragment was identified in the amplification reaction carried out with P2 primer. The 1.2-kb fragment was inserted into the pCR II vector (TA cloning kit, Invitrogen, San Diego, CA), and three clones were selected by use of the human Duffy cDNA probe and sequenced. Sequences of these identical clones were used to design primers for the amplification of Dfy.

Cloning and Sequencing Bone Marrow Dfy cDNA

Mouse bone marrow mRNA and the Marathon RACE (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) kit were used for first- and second-strand cDNA synthesis. Gene-specific primers were designed by use of the sequences of exon 2 of the mouse Dfy. Extaq (TaKaRa Biomedicals, Pan Vera Corp.) DNA polymerase was used in the 5′ and 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) reactions. The 5′ and 3′ RACE fragments were inserted into pCR II vector, cloned, and sequenced. The full-length coding sequences of mouse Dfy cDNA were obtained with two primers designed from the sequences at the very ends of the 5′ and 3′ RACE fragments. The Pfu (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) DNA polymerase was used in these reactions. The amplified cDNA product was subcloned with the pCR-Script SK(+) plasmid (Stratagene) and sequenced. The DNASIS sequence analysis system (Hitachi Software Engineering America, San Bruno, CA) was used for computer analysis of DNA and protein alignments.

Primer Extension

The primer extension was performed as explained (Chaudhuri et al. 1993).

Construction of Expression Vector and Transfection

The mouse bone marrow mRNA was amplified by RT–PCR, by use of 5′-end and 3′-end specific primers, containing KpnI and BamHI restriction sites, respectively. The amplified products were digested with KpnI and BamHI enzymes and ligated to pREP4 expression vector (Invitrogen). The cells were suspended in a phosphate-buffered saline solution containing 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.4) and 40 μg of plasmid cDNA. Transfection was performed with the Gene Pulser electroporation system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules CA). Stable transfected cells were selected by adding 200 μg/ml of hygromycin to the medium. Mock-transfected K562 cells were transfected with the same plasmid lacking the cDNA for the mouse Duffy-like protein.

Chemokine Binding Analyses

125I-Labeled MGSA (sp. act. 2200 Ci/mmole) was obtained from DuPont NEN (Boston, MA). Murine and rat RANTES were gifts from J. Boyd (Pfizer), murine MCP-1 and human and murine MIP-1α and MIP-1β were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Rat GROα and GROβ and murine Eotaxin were obtained from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ).

The chemokine-binding assays in mouse erythrocytes and K562 cells stably expressing mouse Duffy-like protein were performed as explained elsewhere (Neote et al. 1993; Chaudhuri et al. 1994). All reactions were performed in duplicate and the binding assays were repeated twice. The binding data and the dissociation constant (KD) were determined as described (Neote et al. 1993, 1994; Chaudhuri et al. 1994).

Linkage Analyses

Exon 2 of Dfy was used as a probe in Southern blot hybridizations performed as described (Johnson et al. 1992). The genetic map of Dfy was determined by segregation analysis of a mouse interspecific backcross DNA panel derived from mating (C57BI/6J × SPRET/Ei) F1 hybrid females with SPRET/Ei males and designed MMR–BSS. The MMR-BSS panel consists of 144 animals that have been typed for >300 different polymorphic loci (Johnson et al. 1994). The computer program Map Manager was used for linkage and haplotype analysis (Manly 1993).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. M. Reid and Ms. Jill Story from the Laboratory of Immunohematology for erythrocyte antigen typing. We thank Ms. T. Huima and Ms. Y. Oksov for the art work and Ms. V.M. Sarnicole for secretarial assistance. This research was partially supported by grant HL 53927 and SCOR (Specialized Center of Research) grant HL 54459 to A.O.P. from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health and grant GM 46697 to K.R.J. from National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institutes of Health.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL opogo@nybc.org; FAX (212) 570-3195.

REFERENCES

- Chaudhuri A, Polyakova J, Zbrzezna V, Williams K, Gulati S, Pogo AO. Cloning of glycoprotein D cDNA, which encodes the major subunit of the Duffy blood group system and the receptor for the Plasmodium vivax malaria parasite. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1993;90:10793–10797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri A, Zbrzezna V, Polyakova J, Pogo AO, Hesselgesser J, Horuk R. Expression of the Duffy antigen in K562 cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:7835–7838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri A, Polyakova J, Zbrzezna V, Pogo AO. The coding sequence of Duffy blood group gene in humans and simians: Restriction fragment length polymorphism, antibody and malarial parasite specificities, and expression in nonerythroid tissues in Duffy-negative individuals. Blood. 1995;85:615–621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri A, Nielsen S, Elkjaer M-L, Zbrzezna V, Fang F, Pogo AO. Detection of Duffy antigen in the plasma membranes and caveolae of vascular endothelial and epithelial cells of nonerythroid organs. Blood. 1997;89:701–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins A, Keast BJ, Dracopoli N, Shield DC, Morton NE. Integration of gene maps: Chromosome 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1992;89:4598–4602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darbonne WC, Rice GC, Mohler MA, Apple T, Hebert CA, Valente AJ, Baker JB. Red blood cells are a sink for interleukin 8, a leukocyte chemotaxin. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:1362–1369. doi: 10.1172/JCI115442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donahue RP, Bias WB, Renwick JH, McKusick VA. Probable assignment of the Duffy blood group locus to chromosome in man. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1968;61:949–955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.61.3.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelman DM, Steitz TA, Goldman A. Identifying nonpolar transbilayer helices in amino acid sequences of membrane proteins. Ann Rev Biophys Chem. 1986;15:321–353. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.15.060186.001541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faisst S, Meyer S. Compilation of vertebrate-encoded transcription factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:3–26. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederick M, Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith HA, Struhl K. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons/Greene; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Graham GJ, MacKenzie J, Lowe S, Tsang ML-S, Weatherbee JA, Issacson A, Medicherla J, Fang F, Wilkinson PC, Pragnell IB. Aggregation of the Chemokine MIP-1α is a dynamic and reversible phenomenon. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:4974–4978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadley TJ, Miller LH, Hayes JD. Recognition of red cells by malaria parasites: The role of erythrocyte-binding proteins. Transfus Med Rev. 1991;2:108–122. doi: 10.1016/s0887-7963(91)70198-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadley TJ, Lu Z, Wasniowska K, Martin AW, Peiper SC, Hesselgesser J, Horuk R. Postcapillary venule endothelial cells in kidney express a multispecific chemokine receptor that is structurally and functionally identical to the erythroid isoform, which is the Duffy blood group antigen. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:985–991. doi: 10.1172/JCI117465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann E, Rapoport TA, Lodish HF. Predicting the orientation of eukaryotic membrane spanning proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1989;86:5786–5790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.15.5786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horuk R. The interleukin-8 receptor family: From chemokines to malaria. Immunol Today. 1994;15:169–174. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90314-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horuk R, Wang Z-X, Peiper SC, Hesselgesser J. Identification and characterization of a promiscuous chemokine-binding protein in a human erythroleukemic cell line. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:17730–17733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isegawa Y, Sheng J, Sokawa Y, Yamanishi K, Nakagomi O, Ueda S. Selective amplification of cDNA sequence from total RNA by cassette-ligation mediated polymerase chain reaction (PCR): Application to sequencing 6.5 kb genome segment of hantavirus strain B-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1992;6:467–475. doi: 10.1016/0890-8508(92)90043-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto S, Li J, Omi T, Ikemoto S, Kajii E. Identification of a novel exon and spliced form of Duffy mRNA that is the predominant transcript in both erythroid and postcapillary venule endothelium. Blood. 1996;87:378–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KR, Cook SA, Davisson MT. Chromosomal localization of the murine gene and two related sequences encoding high-mobility-group 1 and Y proteins. Genomics. 1992;12:503–509. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(92)90441-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KR, Cook SA, Davisson MT. Identification and genetic mapping of 151 dispersed members of 16 ribosomal protein multigene families in the mouse. Mamm Genome. 1994;5:670–687. doi: 10.1007/BF00426073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopito RR, Andersson MA, Lodish HF. Multiple tissue-specific sites of transcriptional initiation of the mouse anion antiport gene in erythroid and renal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1987;84:7149–7153. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.20.7149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak M. The scanning model for translation: An update. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:229–241. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.2.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macleod K, Leprince D, Stehelin D. The ets gene family. Trends Biohem Sci. 1992;17:251–256. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(92)90404-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallinson G, Soo KS, Schall TJ, Pisacka M, Anstee DJ. Mutations in the erythrocyte chemokine receptor (Duffy) gene: The molecular basis of the Fya/Fyb antigens and identification of a deletion in the Duffy gene of an apparently healthy individual with the Fy(a−b−) phenotype. Br J Haematol. 1995;90:823–829. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1995.tb05202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly KF. A Macintosh program for storage and analysis of experimental genetic mapping data. Mamm Genome. 1993;4:303–313. doi: 10.1007/BF00357089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh WL. Present status of the Duffy blood group system. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 1975;5:387–412. doi: 10.3109/10408367509107049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall RD. Glycoproteins. Annu Rev Biochem. 1972;41:673–702. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.41.070172.003325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew S, Chaudhuri A, Murty VVVS, Pogo AO. Confirmation of Duffy blood group antigen locus (FY) at 1q22 q23 by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1994;67:68. doi: 10.1159/000133801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis MH, Miller LH. Malaria, erythrocyte receptors and the Duffy blood group system. In: Steane EA, editor. Cellular antigens and disease. Washington, DC.: American Association of Blood Banks; 1977. pp. 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Miller LH, Mason SJ, Dvorak JA, McGinniss MH, Rothman KI. Erythrocyte receptors for (Plasmodium knowlesi) malaria: Duffy blood group determinants. Science. 1975;189:561–563. doi: 10.1126/science.1145213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LH, Mason SJ, Clyde DF, McGinniss MH. The resistance factor to Plasmodium vivax in Blacks: The Duffy-blood-group genotype, FyFy. N Engl J Med. 1976;295:302–304. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197608052950602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell PJ, Timmons PM, Hebert JM, Rigby PWJ, Tjian R. Transcription factor AP-2 is expressed in neural crest cell lineages during mouse embryogenesis. Genes & Dev. 1991;5:105–119. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller FU, Boknik P, Horst A, Knapp J, Linck B, Schmitz W, Vahlensieck U, Bohm M, Deng MC, Scheld HH. cAMP response element binding protein is expressed and phosphorylated in the human heart. Circulation. 1995;92:2041–2043. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.8.2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munson PJ, Rodbard D. Ligand: A versatile computerized approach for characterization of ligand-binding systems. Anal Biochem. 1980;107:220–239. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90515-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy PM. The molecular biology of leukocyte chemoattractant receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:593–633. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.003113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neote K, Darbonne W, Ogez J, Horuk R, Schall TJ. Identification of a promiscuous inflammatory peptide receptor on the surface of red blood cells. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:12247–12249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neote K, Mak JY, Kolakowski LF, Schall TJ. Functional and biochemical analysis of the cloned Duffy antigen: Identity with the red blood cell chemokine receptor. Blood. 1994;84:44–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palatnik M, Rowe AW. Duffy and Duffy-related human antigens in primates. J Hum Evol. 1984;13:173–179. [Google Scholar]

- Peiper S, Wang Z-X, Neote K, Martin AW, Showell HJ, Conklyn MJ, Ogborne K, Hadley TJ, Hesselgesser J, Horuk R. The Duffy antigen/receptor for chemokines (DARC) is expressed in endothelial cells of Duffy negative individuals, who lack the erythrocyte receptor. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1311–1317. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.4.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren S, Li J, Atweh GF. CACCC and GATA-1 sequences make the constitutively expressed α-globin gene erythroid-responsive in mouse erythroleukemia cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:342–347. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.2.342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito I, Stark GR. Charomids: Cosmid vectors for efficient cloning and mapping of large or small restriction fragments. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1986;83:8664–8668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.22.8664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo MC, Soo KS, Zlotnik A, Schall TJ. Chemokine class differences in binding to the Duffy antigen-erythrocyte chemokine receptor. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25348–25351. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang TK, Leto TL, Correas I, Alonso MA, Marchesi VT, Benz EJ. Selective expression of an erythroid-specific isoform of protein 4.1. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1988;85:3713–3717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.11.3713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tournamille C, Colin Y, Cartron J-P, Le Van Kim C. Disruption of a GATA motif in the Duffy gene promoter abolishes erythroid gene expression in Duffy-negative individuals. Nature Genet. 1995a;10:224–228. doi: 10.1038/ng0695-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tournamille C, Gane P, Cartron J-P, Colin Y. Molecular basis and PCR-DNA typing of the Fya/Fyb blood group polymorphism. Hum Genet. 1995b;95:407–410. doi: 10.1007/BF00208965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin JH, Cowie A, Lachance P, Hassell JA. Molecular cloning and characterization of PEA3, a new member of the Ets oncogene family that is differentially expressed in mouse embryonic cells. Genes & Dev. 1992;6:481–496. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.3.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuchenko O, Wehnert M, Bailey J, Sheng Sun Z, Chi Lee C. Isolation, mapping, and genomic structure of an X-linked gene for a subunit of human mitochondrial complex I. Genomics. 1996;37:281–288. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]