Abstract

An extensive physical map of the Leishmania major Friedlin genome has been assembled by the combination of fingerprint analysis of a shuttle vector cosmid library and probe hybridization. The integrated data obtained for 9004 fingerprinted clones and 974 probes have placed 91.2% of the 33.58-Mb genome into contigs representing each of the 36 chromosomes. This first-generation map has already provided a suitable framework for both high-throughput DNA sequencing and functional studies of the L. major parasite.

Leishmania is a flagellated protozoan parasite belonging to the family Trypanosomatidae. The 13 different species of Leishmania are responsible for a wide spectrum of human disease occurring mostly in the tropics and subtropics, although cases in North America have been documented (McHugh et al. 1996). Found in parts of Asia, the Mediterranean region, and South America, there are estimated to be over 2 million new cases of leishmaniasis each year in 88 countries, with 367 million people at risk (WHO 1995). Leishmaniasis thus constitutes a major threat to human health.

The parasite is digenic; the extracellular, flagellated forms of Leishmania major differentiate from noninfective promastigotes to infective metacyclics in the alimentary tract of their dipteran (sandfly) vector. After inoculation into the mammalian host, the parasites become intracellular, entering macrophages and differentiating into nonmotile amastigotes. Infective parasites are able to resist the action of resident hydrolytic enzymes, inhibit activation of the oxidative burst, and mitigate the immunological attack of the host (Bard 1989; Killick-Kendrick 1990; Blackwell 1996; Mauel 1996). As a result, there is considerable worldwide interest in determining the factors that contribute to Leishmania’s efficiency as a parasite.

As a eukaryote, Leishmania is atypical. Genes are often organized in tandem repeats, many of which are transcribed polycistronically. Nonrepeated genes of related function can also occur in long transcription units, akin to operons in prokaryotes. Extensive post-transcriptional processing is then required to yield mature mRNAs, including the trans-splicing of a 39-nucleotide spliced leader (SL, or miniexon-derived) RNA onto the 5′ ends of all mRNA molecules (Miller et al. 1986; Ramamoorthy et al. 1996). In contrast, no introns have been detected, removing a requirement for cis splicing. Hence, Leishmania species are the subject of fundamental interest with respect to the evolution of gene regulatory mechanisms, as well as for the exploitation of these properties for the development of new methods of control.

The application of standard genetic techniques to the study of Leishmania has been hampered by two factors: (1) No sexual cycle has been observed; and (2) the chromosomes do not condense at any phase of the cell cycle. However, the refinement of pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) methods over the last 10 years has enabled a molecular “karyotype” for the various Leishmania species to be obtained (Samaras and Spithill 1987; Pagès et al. 1989; Bastien et al. 1992). Typically, the genome of Leishmania comprises ∼25 visible chromosomal bands, with a total haploid genome size of approximately 35 Mb. A genome of this size is amenable to dissection by complementary mapping technologies. To achieve this goal, the Leishmania Genome Network (LGN), supported by United Nations Development Programme/World Bank/World Health Organization (WHO), was set up in 1995.

Until relatively recently, characterization of the Leishmania genome relied almost exclusively on the identification of the individual chromosomes (Samaras and Spithill 1987), typically by the use of gene and/or anonymous DNA probes. More recent studies, by the use of 244 probe loci, enabled 36 physical linkage groups to be defined, and a genome size of ∼35 Mb to be calculated (Wincker et al. 1996). Importantly, the physical linkage groups exhibited conservation among the Old World species of Leishmania, suggesting that overall chromosomal structure and gene order might have been maintained despite speciation and concomitant chromosome size variability (Wincker et al. 1997). This significant observation vindicated the use of a single species of Leishmania as a working model of the genus and provided a multispecies method for the chromosomal assignment of DNA markers in Leishmania. The LGN adopted the virulent L. major Friedlin strain (MHOM/IL/81/Friedlin) as the reference organism for genome mapping (for review, see Ivens and Blackwell 1996; Ivens and Smith 1997).

Eukaryotic organisms with small genomes (e.g., Caenorhabditis elegans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae) have been studied extensively using clone-based methods (cosmids), leading onto large-scale sequencing projects (Sulston et al. 1992; Waterston and Sulston 1995; Dujon 1996). Adopting similar approaches, we have constructed a physical map of the L. major Friedlin genome. A shuttle–vector cosmid library of 9216 clones (ninefold genome coverage) was analyzed by fingerprinting. Assembled into overlapping clone contigs, the clones have been assigned chromosomal map locations by the hybridization of cosmid-derived markers to PFGE-separated chromosomes and high-density gridded colony arrays.

This approach has not only resulted in the joining of contigs but has also facilitated the identification of “tile sets,” the minimum number of clones required to cover individual chromosomes. A directed approach to the sequencing of the entire L. major Friedlin genome can now be adopted.

The data presented in this paper can be viewed in a number of ways:

On the LGN World Wide Web site (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/parasites/leish.html).

As a fully annotated form, which can be downloaded from the LGN ACeDB-based database LeishDB (accessed via the address given above).

Interactively in ACeDB (ACeDB software not required) from the U.K. Medical Research Council-funded Human Genome Mapping Project Resource Centre WWW site (http://www.hgmp.mrc.ac.uk/Public/genome-db.html).

Requests for clones and other information should be directed in the first instance to A.I.

RESULTS

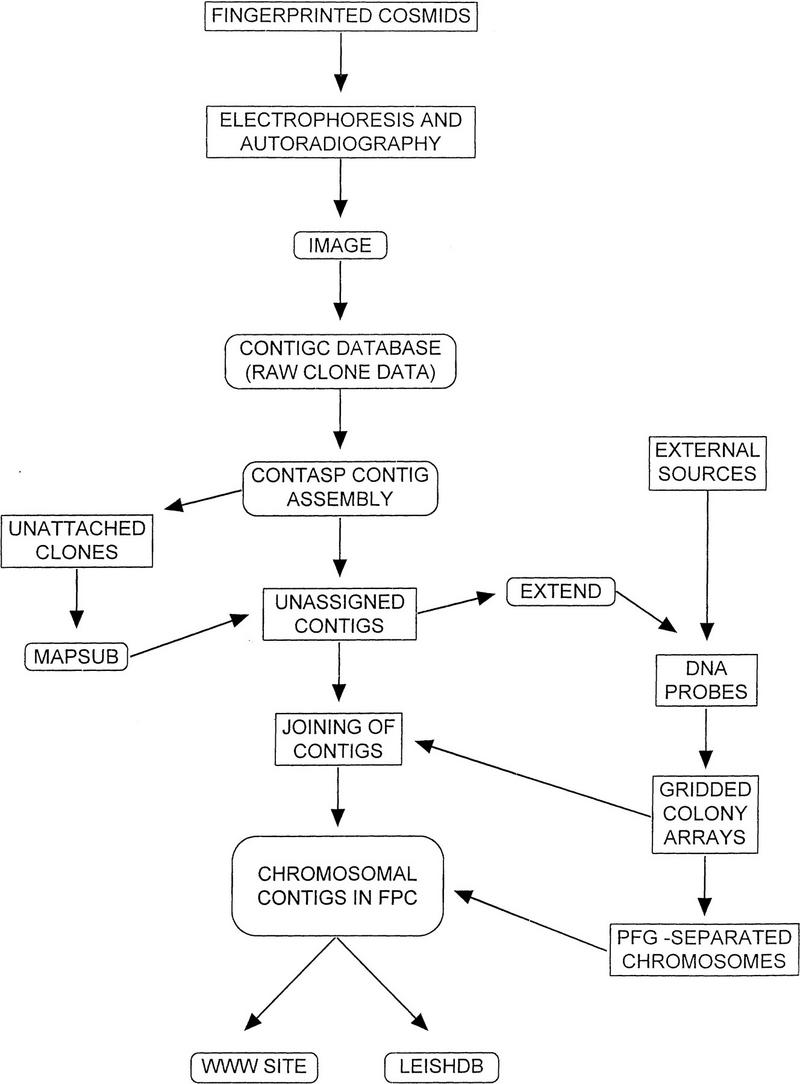

A number of different approaches were adopted during the course of these studies. A flow diagram outline of the overall process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The processes involved in the construction of the genome map. A flow chart detailing the inter-related activities involved in the construction of the physical map of L. major Friedlin. Rounded boxes indicate computer-based analyses.

Fingerprinting

Of the 9216 clones that constitute the cLHYG cosmid library, fingerprints were obtained for 9004 clones (97.7%). Approximately 100 clones appeared to contain either no insert or had undergone rearrangement, as judged by electrophoretic mobilities of the vector fragments. Contigs, assembled by CONTASP software, were subsequently imported into the FPC package. Contigs containing three or fewer clones were disassembled, yielding 545 contigs (70% of fingerprinted clones placed in contigs; Ivens and Smith 1997). Potential end–end joins were identified by the software package EXTEND for subsequent confirmation by hybridization studies. A significant number of clones (345, ∼4%) exhibited <10 fingerprint bands. These were not assembled into contigs by the CONTASP software and required either manual editing or analysis by hybridization.

PFGE Separation of Chromosomes and Mapping of Markers

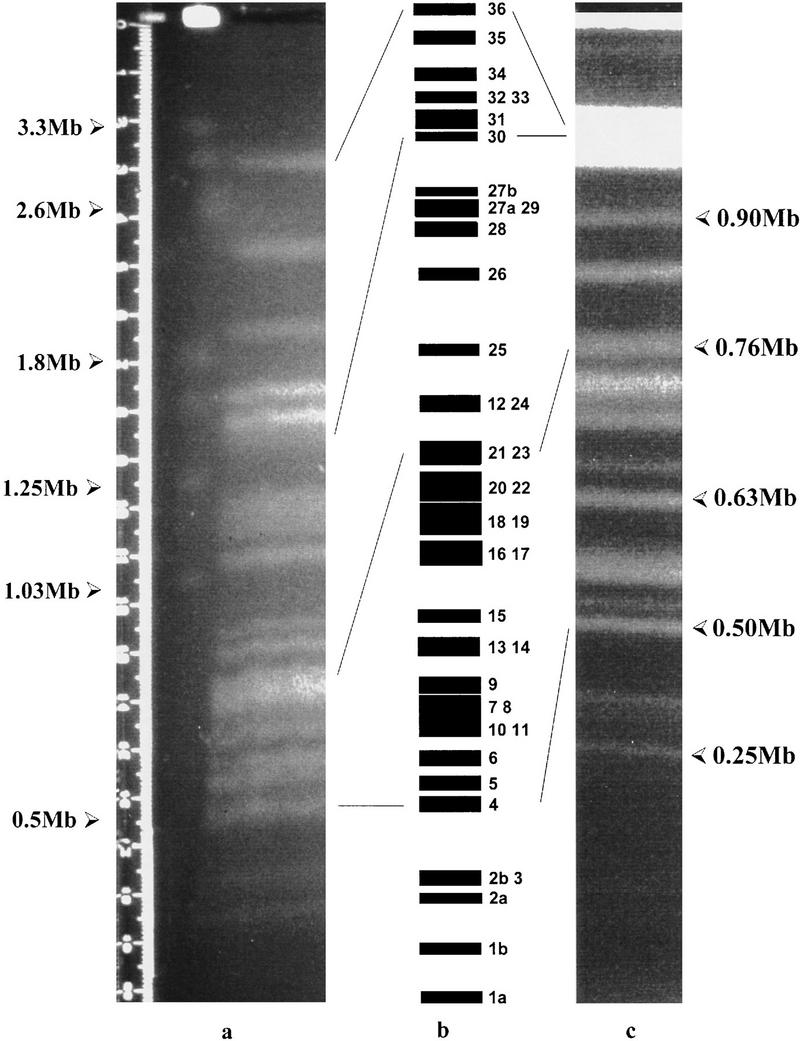

PFGE parameters were optimized for the separation of L. major Friedlin chromosomes (285 kb–2.8 Mb). Using 24-cm gels, a minimum of two sets of conditions were required. Although many chromosomes could be identified individually, ∼51% of the genome by size could not be resolved because of comigration. It is thus likely that the map locations of probes hybridizing to these chromosomes (7–11, 13/14, 16/17, 18/19/20/22, 21/23, 12/24, 27/29, 32/33) can only be ascertained definitively by the application of the multispecies approach described by Wincker et al. (1997). If the number of chromosomes is conserved between the different species of Leishmania, the data obtained from PFGE analysis suggest that the size of the L. major Friedlin genome is ∼33.58 Mb (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

PFGE separation of L. major Friedlin chromosomes. (a) Separation of the larger chromosomes: Agarose-embedded L. major Friedlin DNA was prepared as described in Methods and subjected to PFGE [0.8% agarose (GIBCO), Bio-Rad DRII apparatus, 100 V, 1000- to 100-sec ramp, 250 hr, 4°C; electrophoresis buffer was changed after 90 hr]. The chromosomes of S. cerevisiae YNN295 (Bio-Rad) and H. wingiae (Promega) were used as molecular mass markers. Sizes are indicated. The chromosomes were visualized under UV after staining with ethidium bromide. (b) Ideogram of the L. major Friedlin karyotype. Numbering of the chromosomes was derived from this study and Wincker et al. (1996). Lines indicate the relative mobilities of selected chromosomes in panels a and c. (c) Separation of the smaller chromosomes: Agarose-embedded L. major Friedlin DNA was prepared as above but separated under different PFGE conditions [1.0% agarose (GIBCO), Bio-Rad DRII apparatus, 150 V, 140- to 90-sec ramp, 110 hr, 4°C].

Loci of biological interest, in particular ESTs, had already been mapped to the individual chromosomes of a number of Leishmania species (Wincker et al. 1996), although a definitive karyotype for L. major Friedlin had not been determined. Gridded colony arrays and PFGE-separated chromosomes were hybridized with ESTs, concentrating initially on those that had been mapped by Wincker et al. (1996). The data were used to allocate numbers to the chromosomes. To date, we have hybridized 102 EST markers to gridded colony arrays and PFGE strips; colony array, and some PFGE hybridization data for an additional 166 ESTs are available.

The probe-based approach was also employed to facilitate joining of contigs assembled by fingerprinting data. Five hundred contig-end probes (CEPs) (see Methods) were isolated from cosmids at the ends of contigs and subsequently used to screen both the gridded colony arrays and PFGE strips. Hybridization data have now been obtained for a total of 974 markers (826 with mapping information), and of these, 755 (718 with mapping information) are from this laboratory. Of the 826 probes that have associated chromosomal mapping information, 114 hybridized to more than one chromosome or could not be mapped definitively (data not shown).

High-density grid hybridization data gave rise to a number of observations. The average number of positives identified by probes (excluding whole-chromosome probes) was 24, although a significant proportion was thought to be false positives. An estimate for this was obtained by adding the number of contig 0 (unattached clone) positives to those hybridizing fewer than three times to a contig. Twenty-seven percent of all hybridization data was to unattached clones, and each probe identified an average of 5.8 contigs, yielding a “probable” false-positive estimate of 47%. This was achieved despite careful attention being paid to the stringency of hybridization and posthybridization washes. The nominally false-positive data were not exclusively instances of weak hybridization; there were numerous examples of strongly positive hybridization to clones that could not be placed in a given contig by the fingerprint data. Caution was required when manually placing or moving clones into contigs on the basis of single hybridization results, as these clones frequently proved to be false positives when DNA sequence data were obtained (P. Myler, pers. comm.). Accordingly, all clones had to be positive for at least two probes before being placed in a contig; these artificial movements have been identified by comments in the FPC clone database.

A similar, though less marked, observation was made for a proportion of the probes hybridized to PFGE-separated chromosomes: The vast majority of the colony array data obtained for multilocus probes would identify a single chromosomal contig. In effect, this suggested that several of the multilocus probes could tentatively be reclassified as single loci, although this has not been done. Taking the above aspects into consideration, hybridization data were deemed valid only if they identified overlapping cosmid clones; adopting this criterion, analysis of the hybridization data identified 175 contig-joining events, 44 of which involved more than one probe.

A simple measure of probe utility “confidence” was obtained. Calculated as the proportion of most-valid positive hybridization, the average confidence value for all probes was 0.44. A higher value was obtained for CEP markers (0.50); the average confidence value for the EST probes was considerably poorer (0.31). Simple repeats in the untranslated regions may account for this, although the hypothesis was not investigated further. It was also observed that EST probes frequently hybridized to cosmid clones known to contain the miniexon gene array, a result consistent with the SL sequence being present in each of the EST clones.

The use of chromosomal contigs has also enabled locations for uncertain (114) or unmapped (146) probes to be tentatively inferred. The high-density grid hybridization data were analyzed; the chromosome contig that contained the highest number of positives was deemed to be the likely site of the locus. A confidence cut-off of 0.25 was chosen arbitrarily, below which point an assignment was not made. When performing the analysis for EST markers, chromosome 2 was excluded, as it is the site of the miniexon gene array. Of the 260 markers with uncertain or unknown map locations, 172 (66.2%) could be assigned a tentative chromosomal assignment (data not shown).

Chromosome Coverage

Contigs that could be assigned map locations on the basis of single-locus probe hybridization data were placed in chromosome contigs (e.g., chromosome 1 into contig 1) for ease of analysis. Chromosome contig sizes were determined as described in Methods. Sub-contigs within the chromosomal contigs that could not be joined satisfactorily by either fingerprint overlap or hybridization data were separated by uniformly sized gaps.

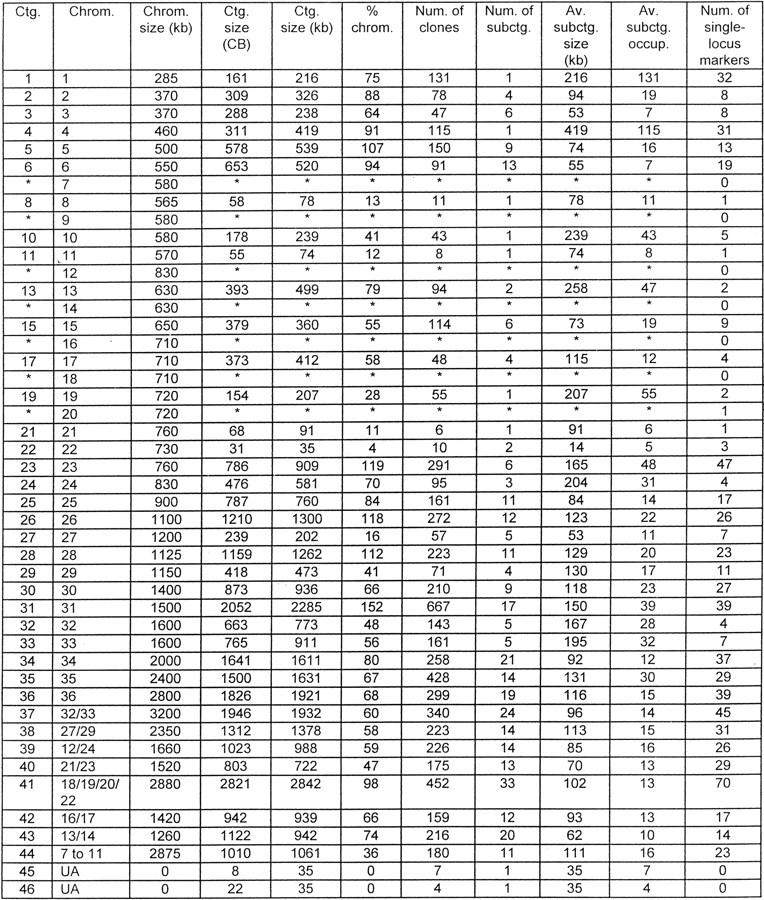

As described above, comigration of L. major Friedlin chromosomes precluded the simple assignment of markers; accordingly, contigs representative of these unresolved chromosomes were also generated (e.g., contig 37 for chromosome 32 or 33). Summing the data for all contigs, the total coverage is 30.65 Mb (91.3% of the genome; Table 1). The amount of 30.61 Mb (91.2% of the genome) has been placed in chromosomal contigs (numbered 1–44), with an average subcontig size of 125 kb. Individual chromosome contigs (contigs 1–36) account for 19.81 Mb (59.0%), with the balance (10.80 Mb, 32.2%) assigned to comigrating chromosomes. Only two small contigs (contigs 45 and 46, assigned a minimum size of 35 kb each), which likely contain telomeric and/or subtelomeric sequences, could not be assigned to a single specific chromosome. As telomeric repeat sequences are under-represented in the cosmid library (only 65 positives for 72 loci), it is likely that the genome coverage figures given above are conservative.

Table 1.

Contig Coverage of the L. major Friedlin Genome

|

Subcontigs, mapped to individual chromosomes by DNA marker loci, were placed in representative chromosomal contigs. The sizes of these contigs were estimated from CB coverage (see Methods for calculation details), with the exception of contigs 45 and 46 (8 and 22 CBs, respectively), which were assigned a default minimum size of 35 kb.

(*)No significant colony array hybridization data for single-locus markers assigned to this chromosome, so contigs not assembled (but see contigs 37–44). (CB) Consensus bands; (UA) unable to assign contig to a specific chromosome.

Sequencing the L. major Friedlin Genome

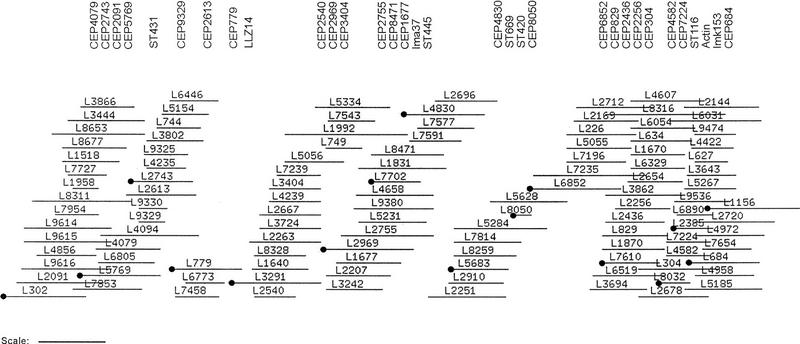

Having constructed chromosomal contigs, it is possible to determine tile sets for sequencing purposes. This laboratory is particularly interested in chromosomes 30 (1.4 Mb), 23 (760 kb), and 4 (460 kb) (Flinn and Smith 1992; Kelly et al. 1995; McKean et al. 1997). A whole-chromosome probe, isolated from a pulsed-field agarose gel, was used to identify contigs from chromosome 4. Subsequently, the data from 32 other probes were used to confirm the order of the subcontigs identified. SEGMAP software was initially employed to establish the most likely hybridization data-based clone order, but the high level of false positives observed precluded its universal application without extensive data manipulation. The size of the contig was estimated at 395 kb (SEGMAP) or 419 kb (FPC), ∼90% of the chromosome. A tile set of 16 cosmid clones was selected. A modified contig display from FPC is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Minimum tile set for chromosome 4. L. major Friedlin cosmid clones were fingerprinted, as detailed in Methods, prior to contig assembly by CONTASP and FPC v. 2.8.2 software. Subcontigs shown to contain chromosome 4 marker loci were joined by (1) the application of additional software packages: MAPSUB (identified loose fingerprint matches), EXTEND (identified potential end–end joins), and (2) hybridization data (assigned and joined subcontigs), to yield an integrated map. The contig display from FPC formed the basis of this diagram. All clones that constitute the contig, including those that have been buried, are shown as horizontal lines. DNA hybridization probes are shown along the top (see Methods for probe descriptions). A minimum tile set (•) was chosen for DNA sequencing purposes. The scale bar represents 26 consensus bands (∼35 kb).

A problem was encountered with L8050, the only clone in the cosmid library positive for markers ST445 and ST669. CEP8050.1.2, a probe generated from the cosmid, positioned L8050 within the contig; this was confirmed by additional probe data from clone L4830 (CEP4830.1.7). However, these probe data are inconsistent, as clones positive for both CEP8050.1.2 and CEP4830.1.7 should also be positive for markers ST445 and ST669. It seems likely that this region of the chromosome is unstable and that cosmids positive for the two CEP probes no longer contain the loci identified by the ST probes. For this reason, the region encompassing the ST445/ST669 loci was deliberately over-represented in the tile set. DNA sequence information obtained by shotgun cloning of PFGE-separated chromosome 4 should eradicate this anomaly.

DISCUSSION

Contig Assembly

Variation in contig depth was observed. The data suggest that the library was over-representative for certain (probably coding) regions, and under-represented for others (e.g., telomere repeat sequences). It thus appears that the Leishmania genome is similar to many other genomes in that it contains sequences not readily maintained in Escherichia coli cloning vectors. Coupled with the use of Sau3AI for cosmid library construction, these factors may have played a part in preventing the assembly of larger initial contigs by CONTASP software. Despite these impediments, it was always possible to identify at least one cosmid, and usually many more, for all 974 DNA marker probes hybridized to the gridded library.

As noted above, a small but significant proportion of fingerprinted clones exhibited very few fingerprint bands. This had two major effects: (1) These clones were not placed into contigs because of the probability cutoff used; and (2) contigs constructed manually from these clones resulted in an incorrect estimate of contig size. As an example, the miniexon gene locus, mapped to chromosome 2, is known to consist of a tandem array of ∼100 identical or nearly identical genes covering ∼50 kb (Iovannisci and Beverley 1989; Fernandes et al. 1994). Fingerprints from cosmid clones containing the miniexon gene sequence typically comprised five strongly labeled bands; clones could therefore not be ordered relative to each other. The small number of bands not only made it impossible to join the miniexon stack to other subcontigs known to map to chromosome 2 but has also led to an underestimate of chromosome 2 contig coverage. Similar problems have been encountered with a number of other tandem arrays, for example, LmcDNA2 and LmcDNA16 (Flinn and Smith 1992; Kelly et al. 1995; McKean et al. 1997), gp63 (Voth et al. 1998), and the histone H1 (sw3) loci (Fasel et al. 1993; Noll et al. 1997). Given this fact, it is possible that many contig size estimations, based solely on the number of consensus bands, under-represent their true sizes and that the physical map presented here is nearer completion than the data suggest.

DNA Probe Hybridization to PFGE-Separated Leishmania Chromosomes

The separation of L. major Friedlin chromosomes could be achieved using a minimum of two sets of electrophoretic conditions, as shown in Figure 2. Modification of these conditions to selectively expand certain size ranges did not result in the complete separation of all chromosomes. Comigration, as evidenced by both staining intensity and hybridization analyses, remains a feature of the L. major Friedlin genome.

A large number of DNA markers, 974, were used in these studies, yielding an average probe density of one per 34.5 kb. Of these markers, 712 (73.1%) mapped to a single locus and were used to assemble the chromosomal contigs. Of the single-locus markers, 255 hybridized as a single band to comigrating chromosomes. To clarify their exact localization, these DNA markers are currently being hybridized to multispecies PFGE blots, thereby taking advantage of interspecies chromosomal size polymorphisms, as described recently by Wincker et al. (1997).

Coverage

The paucity of telomeric sequences in the cosmid library suggested that the coverage figures obtained may be conservative. If telomere and/or subtelomere repeats were to constitute 5–10 kb at the end of each chromosome (totaling 360–720 kb; K. Stuart, pers. comm.), the approximate proportion of nontelomere DNA assigned to chromosomes by this study would be closer to 92.7% of the genome. These figures suggest strongly that despite some variations in contig depth, the coverage of the genome by contigs is close to complete and that the majority of coding sequences have probably been cloned. We do not have sufficient data to determine whether the distribution of genes in the telomere regions of Leishmania is more similar to C. elegans than to Trypanosoma brucei. Are there regulated expression sites at the telomeres of Leishmania as have been observed for the VSG genes in T. brucei (Rudenko et al. 1996)? The answer to this question will highlight the relative importance of possessing physical maps that stretch contiguously from telomere to telomere.

Although it is difficult at this stage to generate accurate figures for the physical extent of the presumed gaps, these could be determined hypothetically by restriction enzyme mapping. In addition, the need for gap closure has initiated a number of supplementary approaches. Cosmid clone end sequencing is particularly useful for determining the extent of clone overlap, whereas the construction and integration of PAC library clone data should enable the majority of gaps to be bridged, confirm the order of subcontigs, and also provide an alternative minimum tile set source for DNA sequencing templates.

DNA sequence data obtained from six chromosome 1 cosmids by the Stuart laboratory, also a member of the LGN, have been submitted to GenBank (1997) and can be accessed via the sequencing page of the LGN WWW site (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/parasites/LGN/leishseq.html). Analysis of the finished sequence data of five cosmids suggests that although the telomere regions have not been sequenced yet, gene density is relatively high. There are 51 potential ORFs within 176.4 kb of sequence, or one gene per 3.46 kb. As a significant proportion of the putative genes are novel, these data underline the high priority of further sequence data acquisition.

Future Benefits and Activities

Ultimately, the development of prophylactic agents for the control and/or eradication of all types of leishmaniasis remains the primary goal of workers doing research on this parasite. A number of benefits will ensue from the physical map of the L. major Friedlin genome and the large quantities of primary DNA sequence data that can be efficiently obtained from this source material. Broad questions as to the behavioral dynamics of the genome can be addressed. Similarity searches of DNA and protein databases have already enabled the identification of orthologs and paralogs of many genes; novel genes have also been identified (see the WWW BLAST analysis pages at http://www.ebi.ac.uk/parasites/LGN/lshblstn.html or lshblstx.html).

The data obtained for these and other genes will provide additional entry points to those studying the functional aspects of parasite virulence that have a direct bearing on the identification of new targets for chemotherapy. Several recently developed techniques are facilitating these investigations. Targeted gene disruption by homologous recombination (Cruz and Beverley 1990; Cruz et al. 1991; Cruz et al. 1993) can generate defined mutants for complementation using shuttle vectors (e.g., cLHYG, the cosmid vector used in these studies; Ryan et al. 1993); random gene inactivation and gene trapping can be achieved by transposon mutagenesis (Gueiros-Filho and Beverley 1997); and the temporal and spatial trafficking of proteins in vivo can be monitored via green fluorescent protein (GFP) constructs (Ha et al. 1996). In the mammalian host, vaccine candidates can be assayed following the inoculation of either recombinant protein or by DNA vaccination (Gardner et al. 1996; Whalen 1996; Ulmer et al. 1996).

All of these approaches will contribute to our understanding of the mechanisms underlying Leishmania infectivity. The physical and biological information gained from the genome mapping and sequencing initiatives will be of value not only to those interested in Leishmania and other trypanosomes but also to those exploring some of the more unusual aspects of eukaryotic gene expression.

METHODS

Fingerprinting

A L. major Friedlin cosmid library of 9216 clones, constructed by ligation of Sau3AI partially digested DNA into the BamHI site of the cLHYG shuttle vector (Ryan et al. 1993), was picked into microtiter plates. The entire library was analyzed by fingerprinting, as described previously (Coulson and Sulston 1988; Ivens and Little 1995). DNA samples were digested with HinfI, the termini end-filled in the presence of [32P]dCTP, and the resulting products separated by electrophoresis (35 W, for ∼90 min) on 4% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels prior to autoradiography. Bacteriophage λ, digested with HinfI and radiolabeled by end-filling in the presence of 35S-labeled dATP, acted as a normalizing internal standard. The cosmid library was also gridded onto nylon membranes (GeneScreen Plus, DuPont) using a Biomek 1000 robotic workstation (Bentley et al. 1992). Membranes were prepared for hybridization by successive treatments with 0.5 m NaOH/1.5 m NaCl, and 1 m sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.8), followed by baking at 80°C and UV cross-linking (Sambrook et al. 1989).

Image and Contig Analysis

Fingerprint autoradiographs were scanned using an Amersham scanner. The resulting image files were analyzed by the IMAGE 2.1 software package to generate a clone fingerprint database. Overlapping fingerprints within this database were initially identified by CONTASP software, using a band match tolerance of 1 mm and a probability cutoff of 1e−07, and contigs viewed using CONTIGC (Sulston et al. 1988, 1989).

Joining of these contigs initially involved MAPSUB analysis, followed by EXTEND (see Fig. 1). The MAPSUB software package matches fingerprints at user-specified tolerance and probability cutoff values. Match likelihood of an unassembled clone database indicated that for an average 26-band clone, the probability cutoff used for contig assembly would only identify clones exhibiting 54% (tolerance, 0.7 mm) or 62.5% (tolerance, 1.0 mm) or greater overlap with another 26-band clone. The application of higher probabilities (e.g., 1e−05, for 42% and 50% overlap, respectively) yielded an unacceptable level of multiply inconsistent overlaps and was disregarded. Although exhaustive match analysis with a probability cutoff of 1e−02 indicated that each clone had, on average, 35 or 44 (tolerance, 0.7 and 1.0 mm, respectively) other matching clones, only a small proportion (8.8% and 7.7%, respectively) matched with a probability below 1e−07. These figures were considerably lower for clones placed at the ends of the contigs (data not shown).

More recently, the FPC (v 2.8.2) software package has been used (C. Soderlund, pers. comm.). The contig data were imported into the FPC software, and contigs were refined by analysis at tolerance 0.7 mm. Subcontigs that could be joined by hybridization data were placed next to each other, separated by 1 consensus band (CB) calculations, whereas unjoined subcontigs have been separated by 10 CB gaps. All subcontig manipulations have been annotated in the publicly available database, LeishDB.

The number of nonvector fragments resolved by the electrophoresis conditions was 26 [±8.5 (1 s.d.)] bands per clone. Assuming that each cosmid clone contains, on average, 35 kb of inserted DNA, each band thus approximates to 1.347 kb; this value was subsequently applied to all CB calculations of contig size and chromosome coverage. The lowest limit of overlap used by the contig assembly software (∼50% cosmid overlap, or 17.5 kb) was used as the minimum gap size. Contig sizes were calculated as follows: [(CB bands) × 1.347]≠[30 × (no. of gaps)] = size (kb). Although this calculation tends to underestimate the true coverage of the individual subcontigs, it compensates for the “false” separation of hybridization-based joining events.

PFGE

Clamped homogeneous electric field PFGE was used to separate the chromosomes of L. major Friedlin (MHOM/IL/81 Friedlin). Parasites were grown at 24°C for 96 hr in vitro [Drosophila Schneider’s medium (GIBCO)/15% heat-inactivated bovine calf serum (GIBCO)/100 μg/ml of gentamycin (Sigma)], harvested by centrifugation, and washed at room temperature in 20 ml of PBS (Coulson and Smith 1990). Following centrifugation, the parasites were thoroughly resuspended in 6 ml of PBS, and an equal volume of prewarmed (50°C) 1% LGT [low gelling temperature (Seaplaque, Flowgen)] agarose/PBS was added. The parasite–agarose mixture was aliquoted (100 μl) into precooled (4°C) block formers (Pharmacia) and allowed to set. Parasites were lysed by extruding the blocks into 40 ml of LiDS mix [1% (wt/vol) lithium dodecylsulfate, 100 mm EDTA, 20 mm Tris-HCl at pH 8.0], followed by incubation at 50°C for 24 hr. Blocks were washed extensively in TE buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, 1 mm EDTA at pH 8.0) prior to electrophoresis in 1× TB, 0.1× E, using either modified Gene Navigator (Pharmacia) or DRII (Bio-Rad) equipment. Pulse times, voltages, and/or agarose concentrations were varied to achieve different size separation ranges; all gels were transferred to GeneScreen Plus nylon membranes for hybridization studies (Sambrook et al. 1989). When chromosomal probes required isolation, LGT agarose was used. Size standards were S. cerevisiae YNN295 (Bio-Rad) or Hansenula wingiae (Promega) chromosomes.

Hybridization Markers

Assembled contigs were analyzed by EXTEND software to identify potential end–end joins, with the resulting data forming the initial basis of the hybridization approach. CEPs were isolated from cosmids located at the ends of contigs. DNAs were isolated using standard miniprep procedures (Ivens and Little 1995) prior to restriction endonuclease digestion (typically PstI) and fragment separation by electrophoresis. Fragments (0.5–3.0 kb), isolated from LGT agarose gels, were subsequently radiolabeled as described below and used as probes against the gridded cosmid colony arrays and PFGE-separated L. major chromosomes.

Several other classes of hybridization probes were employed. ESTs, some previously assigned by Wincker et al. (1996), were provided as PCR products and are prefixed by lm or Lm (Levick et al. 1996; H. Schneider and A. Cruz, pers. comm.). Chromosomally mapped probes, prefixed by ST or ISA, were provided as described (Wincker et al. 1996). “Walking” probes from L. major LV39 are prefixed by LV. Whole-chromosome probes, isolated from PFGE gels as described above, are prefixed by Chr. Probes prefixed by CEP have been described, whereas those suffixed by AB were isolated from anonymous cosmids that gave few (less than six) fingerprint bands. Probes generated by in vitro transcription of cosmid clones (P. Myler, pers. comm.) are either suffixed by T3, T7, and/or PCR or prefixed by 10.

Hybridization

DNA probes were radiolabeled with [32P]dCTP by random priming (Feinberg and Vogelstein 1984) prior to purification by G-50 Sephadex chromatography. Hybridizations were carried out at 65°C in Church buffer (0.5 m NaPi, 7% SDS), and washed at high stringency (0.1× SSC, 0.1% SDS, at 65°C) prior to autoradiography with intensifying screens at −70°C. The locations of positively hybridizing cosmid clones on high-density colony arrays were identified using a template (Ivens and Little 1995).

Acknowledgments

We thank the following: Jon Warner for the L. major cosmid library (constructed using genomic DNA isolated by D.F.S.), Steve Beverley for the cLHYG cosmid shuttle vector, Jennie Blackwell, Horacio Schneider, and Ira Sampaio for EST markers, Angela Cruz for EST hybridization data, Patrick Bastien and Patrick Wincker for ST/ISA probes, Peter Myler for chromosome 1 probe and SEGMAP data, Nicolas Fasel for sw3, Michal Shapira for Hsp83, Paul McKean for pgmr51 and pgmd1, Liz Bates for LmPABPH3, and Arve Osland for clone 7 and clone 9. We also thank Peter Little and Holger Hummerich for access to the Biomek Workstation and for many useful discussions. We acknowledge the Sanger Centre (Cambridge, U.K.) for MAPSUB, CONTASP, CONTIGC, and IMAGE software packages (available by anonymous FTP), Cari Soderlund for FPC v 2.8.2, and Chuck Magness (Washington University, Seattle) for SEGMAP. This research has been funded by the Medical Research Council (MRC) (to A.C.I. and D.F.S., grants G9402457 and G9503213PB, respectively; L.Z. was funded for 10 months from MRC grant G9402457; S.M.L. from grant G9503213PB), The Royal Society (A.C.I., grant 15836), the Nuffield Foundation (A.C.I., grant AT/100/95/0008; 2 months support for H.M.C.), and the Wellcome Trust (A.C.I., grants VS/94/IMP/003 and VS/95/IMP/002). Research in the laboratory of D.F.S. is supported by the Wellcome Trust (no. 039006/Z/93/Z/1.4A/PMC/MW and no. 045493/Z/95/Z/JRS/JH). This investigation also received financial support from the UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR) (D.F.S., grant 950522; support for A.B.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL a.ivens@ic.ac.uk; FAX 44-171-2250960.

REFERENCES

- Bard E. Molecular biology of Leishmania. Biochem Cell Biol. 1989;67:516–524. doi: 10.1139/o89-083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastien P, Blaineau C, Pagès M. Molecular karyotype analysis in Leishmania. In: Avila JL, Harris JR, editors. Subcellular biochemistry. Vol. 18. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1992. pp. 131–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley DR, Todd C, Collins J, Holland J, Dunham I, Hassock S, Bankier A, Gianelli F. The development and application of automated gridding for efficient screening of yeast and bacterial ordered libraries. Genomics. 1992;12:534–541. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(92)90445-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell, J.M. 1996. Genetic susceptibility to leishmanial infections: Studies in mice and man. Parasitology (Suppl.) 112: S67–S74. [PubMed]

- Coulson A, Sulston J. Genome mapping by restriction fingerprinting. In: Davies KE, editor. Genome mapping: A practical approach. Oxford, UK: IRL Press; 1988. pp. 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Coulson RM, Smith DF. Isolation of genes showing increased or unique expression in the infective promastigotes of Leishmania major. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1990;40:63–75. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(90)90080-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz AK, Beverley SM. Gene replacement in parasitic protozoa. Nature. 1990;348:171–174. doi: 10.1038/348171a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz AK, Coburn CM, Beverley SM. Double targeted gene replacement for creating null mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1991;88:7170–7174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz AK, Titus R, Beverley SM. Plasticity in chromosome number and testing of essential genes in Leishmania by targeting. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1993;90:1599–1603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.4.1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dujon B. The yeast genome project: What did we learn? Trends Genet. 1996;12:263–270. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(96)10027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasel NJ, Robyr DC, Mauel J, Glaser TA. Identification of a histone H1-like gene expressed in Leishmania major. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;62:321–323. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90123-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg AP, Vogelstein B. A technique for radiolabeling DNA restriction fragments to high specific activity. Anal Biochem. 1984;137:266–267. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes O, Murthy VK, Kurath U, Degrave WM, Campbell DA. Mini-exon gene variation in human pathogenic Leishmania species. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1994;66:261–271. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)90153-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flinn HM, Smith DF. Genomic organization and expression of a differentially regulated gene family from Leishmania major. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:755–762. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.4.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner MJ, Doolan DL, Hedstrom RC, Wang R, Sedegah M, Gramzinski RA, Aguiar JC, Wang H, Margalith M, Hobart P, Hoffman SL. DNA vaccines against malaria: Immunogenicity and protection in a rodent model. J Pharm Sci. 1996;85:1294–1300. doi: 10.1021/js960147h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueiros-Filho FJ, Beverley SM. Trans-kingdom transposition of the Drosophila element mariner within the protozoan Leishmania. Science. 1997;276:1716–1719. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5319.1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha DS, Schwarz JK, Turco SJ, Beverley SM. Use of the green fluorescent protein as a marker in transfected Leishmania. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;77:57–64. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(96)02580-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iovannisci DM, Beverley SM. Structural alterations of chromosome 2 in Leishmania major as evidence for diploidy, including spontaneous amplification of the mini-exon array. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1989;34:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(89)90009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivens AC, Blackwell JM. Unravelling the Leishmania genome. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1996;6:704–710. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(96)80024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivens AC, Little PFR. Cosmid clones and their application to genome studies. In: Glover DM, Hames BD, editors. DNA cloning 3: Complex genomes. Oxford, UK: IRL Press; 1995. pp. 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ivens AC, Smith DF. A global map of the Leishmania major genome: Prelude to genome sequencing. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1997;91:111–115. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(97)90188-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly BL, Dyall SD, Warner J, Tang J, Smith DF. Chromosomal organization of a repeated gene cluster expressed in mammalian stages of Leishmania. Gene. 1995;163:145–149. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00390-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killick-Kendrick, R. 1990. The life-cycle of Leishmania in the sandfly with special reference to the form infective to the vertebrate host. Ann. Parasitiol. Hum. Comp. (Suppl. 1) 65: 37–42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Levick MP, Blackwell JM, Connor V, Coulson RMR, Miles A, Smith HE, Wan K-L, Ajioka JW. An expressed sequence tag analysis of full-length, spliced-leader cDNA libraries from Leishmania major promastigotes. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;76:345–348. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(95)02569-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauel J. Intracellular survival of protozoan parasites with special reference to Leishmania spp., Toxoplasma gondii and Trypanosoma cruzi. Adv Parasitol. 1996;38:1–51. doi: 10.1016/s0065-308x(08)60032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh CP, Melby PC, LaFon SG. Leishmaniasis in Texas: Epidemiology and clinical aspects of human cases. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;55:547–555. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.55.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKean PG, Delahay R, Pimenta PFP, Smith DF. Characterization of a second protein encoded by the differentially regulated LmcDNA16 gene family of Leishmania major. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1997;85:221–231. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(97)02829-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SL, Landfear SM, Wirth DF. Cloning and characterization of a Leishmania gene encoding a RNA spliced leader sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:7341–7360. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.18.7341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noll TM, Desponds C, Belli ST, Glaser TA, Fasel NJ. Histone H1 expression varies during the Leishmania major life cycle. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1997;84:215–227. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(96)02801-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagès M, Bastien P, Veas F, Rossi V, Bellis M, Wincker P, Rioux JA, Roizes G. Chromosome size and number polymorphism in Leishmania infantum suggest amplification/deletion and possible genetic exchange. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1989;36:161–168. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(89)90188-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramamoorthy R, Donelson JE, Wilson ME. 5′ sequences essential for trans-splicing of msp (gp63) RNAs in Leishmania chagasi. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;77:65–76. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(96)02581-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudenko G, McCulloch R, Dirks-Mulder A, Borst P. Telomere exchange can be an important mechanism of variant surface glycoprotein gene switching in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;80:65–75. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(96)02669-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan KA, Dasgupta S, Beverley SM. Shuttle cosmid vectors for the trypanosomatid parasite Leishmania. Gene. 1993;131:145–150. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90684-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samaras N, Spithill TW. Molecular karyotype of five species of Leishmania and analysis of gene locations and chromosomal rearrangements. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1987;25:279–291. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(87)90092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: A laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Sulston J, Mallet F, Staden R, Durbin R, Horsnell T, Coulson A. Software for genome mapping by fingerprinting techniques. Comput Appl Biosci. 1988;4:125–132. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/4.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston J, Mallet F, Durbin R, Horsnell T. Image analysis of restriction enzyme fingerprint autoradiograms. Comput Appl Biosci. 1989;5:101–106. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/5.2.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston J, Du Z, Thomas K, Wilson R, Hillier L, Staden R, Halloran N, Green P, Thierry-Mieg J, Qiu L, Dear S, Coulson A, Craxton M, Durbin R, Berks M, Metzstein M, Hawkins T, Ainscough R, Waterston R. The C. elegans genome sequencing project: A beginning. Nature. 1992;356:37–41. doi: 10.1038/356037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulmer JB, Sadoff JC, Liu MA. DNA vaccines. Curr Opin Immunol. 1996;8:531–536. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(96)80042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voth, B.R., B.L. Kelly, P.B. Joshi, A.C. Ivens, and W.R. McMaster. 1998. Developmentally expressed Leishmania major gp63 genes encode cell surface leishmanolysin containing distinct signals for GPI attachment. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Waterston R, Sulston J. The genome of Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1995;92:10836–10840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.10836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalen RG. DNA vaccines for emerging infectious diseases: What if? Emerg Infect Dis. 1996;2:168–175. doi: 10.3201/eid0203.960302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wincker P, Ravel C, Blaineau C, Pagès M, Jauffret Y, Dedet J-P, Bastien P. The Leishmania genome comprises 36 chromosomes conserved across widely divergent human pathogenic species. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:1688–1694. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.9.1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wincker P, Ravel C, Britto C, Dubessay P, Bastien P, Pagès M, Blaineau C. A direct method for the chromosomal assignment of DNA markers in Leishmania. Gene. 1997;194:77–80. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00162-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). 1995. WHO Leishmaniasis World Wide Web Home Page. http://www.who.ch/programmes/ctd/diseases/leis/leismain.htm.