Abstract

The development of an enantioselective allylic alcohol dichlorination catalyzed by dimeric cinchona alkaloid derivatives and employing aryl iododichlorides as chlorine sources is reported. Reaction optimization, exploration of the substrate scope, and a model for stereoinduction are presented.

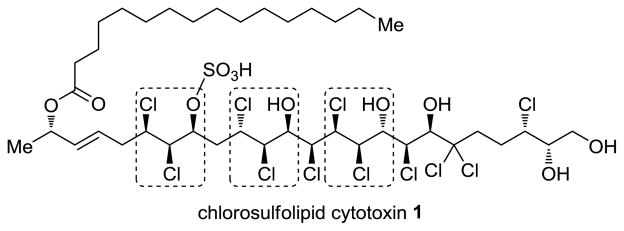

Despite tremendous advances in the development of chiral methods, asymmetric olefin dichlorination1 remains a challenging problem. Such a reaction would be useful for the synthesis of oligo- and polychlorinated compounds.2 Originally discovered from the membranes of freshwater algae,3 chlorosulfolipids have gained significant attention since 20014 due to their putative link to diarrheic shellfish poisoning. Their biosynthesis likely proceeds through a series of site- and stereoselective enzymatic chlorinations of unfunctionalized positions on sulfolipid precursors.5 In contrast, synthetic chemists generally can control chlorination only at functionalized sites. Evaluation of existing synthetic approaches1 and the structure of chlorosulfolipid cytotoxin 1 (the most complex member of the family; see Figure 1)6 suggested a need for asymmetric olefin dichlorination methods, especially those applicable to allylic alcohols. Most recent approaches have relied on substrate control of stereochemistry, and required substrate derivatization (e.g. epoxidation of the olefin1e–g or esterification of an allylic alcohol1h). In the Snyder group’s total synthesis of napyradiomycin A1,1c there is an isolated example of a practical enantioselective olefin dichlorination employing a stoichiometric chiral auxiliary. Although the above methods have been employed in total syntheses of several chlorosulfolipids,7 there remains a need for additional asymmetric dichlorination methods. We present herein the development of an enantioselective dichlorination of allylic alcohols.

Figure 1.

Molecular structure of chlorosulfolipid cytotoxin 1, and opportunities for asymmetric allylic alcohol dichlorination.

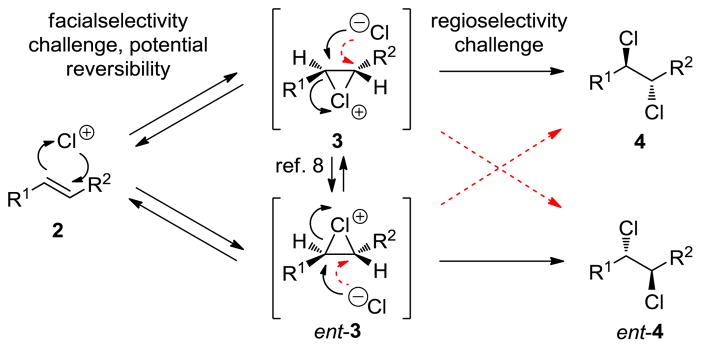

As shown in Scheme 1, olefin dichlorination is a challenging reaction to render enantioselective. The reaction proceeds through an initial electrophilic chlorination (see 2) to form chloronium species 3. Even if this process is rendered facialselective,8 there remains a regioselectivity challenge in the subsequent nucleophilic chlorination; attack of the two chloronium positions of homochiral species 3 leads to opposite antipodes of 4. Additionally, the configurational stability of chloronium species 3 may be degraded by reversibility and/or direct chlorenium transfer to another molecule of the olefinic substrate (2).9

Scheme 1.

Mechanism of Olefin Dichlorination and Challenges for Enantioselectivity

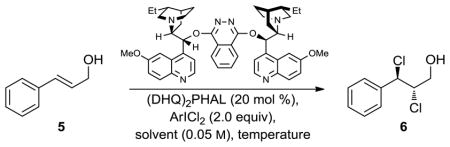

In view of these potential challenges, we selected trans-cinnamyl alcohol (5, Table 1) as a model substrate. The benzylic nature of the intermediate chloronium species would enforce a regiocontrolled chloride attack. The hydroxyl moiety might hydrogen bond with a catalyst or reagent, rigidifying the system and potentially improving stereocontrol. Our first clue suggesting a direction for catalyst screening came from observations that electrophilic halogenation is dramatically accelerated by tertiary amines.10 Screening of common amine catalysts (e.g. proline and imidazolidinone derivatives,11 small peptides,12 and cinchona alkaloids1a,8,13) and a range of chlorine sources (e.g. Cl2 gas, Et4NCl3, and PhICl2) revealed the dimeric cinchona alkaloid derivative (DHQ)2PHAL (commonly employed as a ligand for Sharpless asymmetric dihydroxylation) and PhICl2 as a uniquely promising reagent combination for further studies.

Table 1.

Screening of Reaction Conditions for Enantioselective Di-chlorinationa

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | ArICl2 | Solvent | Temp. (°C) | ee (%)b |

| 1 | PhICl2 | CH2Cl2 | 25 | 22 |

| 2 | PhICl2 | CH2Cl2 | 0 | 23 |

| 3 | PhICl2 | CH2Cl2 | −40 | 41 |

| 4 | PhICl2 | CH2Cl2 | −78 | 82 |

| 5 | PhICl2 | THF | −78 | <5 |

| 6 | PhICl2 | EtOAc | −78 | 10 |

| 7 | PhICl2 | Et2O | −78 | <5 |

| 8 | PhICl2 | CH2Cl2: hexanes (1:1) | −78 | 75 |

| 9 | PhICl2 | CH2Cl2: PhMe (1:1) | −78 | 75 |

| 10 | o-Me(C6H4)ICl2 | CH2Cl2 | −78 | 56 |

| 11 | p-Ph(C6H4)ICl2 | CH2Cl2 | −78 | 85 |

| 12 | p-t-Bu(C6H4)ICl2 | CH2Cl2 | −78 | 73 |

Reactions were performed on 7 mg (50 μmol) scale, and run to completion (TLC analysis).

Determined by chiral HPLC analysis.

Interestingly, the quality of PhICl2 proved to be critical, with the use of PhICl2 generated from PhI and NaOCl (Chlorox® or a solution from Sigma–Aldrich) resulting in poor reproducibility. However, employing PhICl2 freshly prepared from PhI and Cl2 gas yielded consistent results. Furthermore, catalyst aging in the presence of PhICl2 degraded both reactivity and selectivity. Therefore, since the uncatalyzed reaction is very slow, the catalyst was added last to a reaction mixture already containing the substrate and PhICl2. An initial addition of 10 mol % catalyst followed by slow addition of another 10 mol % catalyst gave the best results.

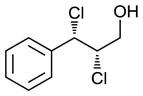

Under these conditions, (DHQ)2PHAL-catalyzed dichlorination of trans-cinnamyl alcohol (5) by PhICl2 at ambient temperature (Table 1, entry 1) afforded dichloride 6 in 22% ee. Lowering the temperature (entries 2–4) prolonged reaction times, but improved enantioselectivity. A solvent screen (entries 4–7) revealed CH2Cl2 to be uniquely suitable. Mixed solvents containing CH2Cl2 could also be used (entries 8 and 9), but the reactions became more sluggish (likely due to reduced solubility of the catalyst and PhICl2), and selectivities were not improved. An exploration of alternative aryl iododichlorides (entries 10–12) revealed some effects on the level of enantioselectivity, with the use of p-Ph(C6H4)ICl2 (entry 11) delivering dichloride 6 in 85% ee.

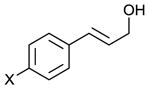

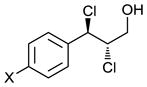

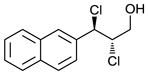

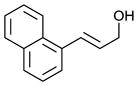

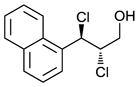

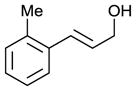

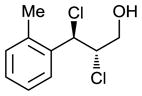

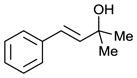

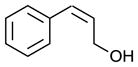

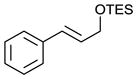

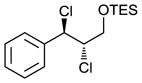

Scaling up the reaction conditions in entry 11 of Table 1 and reducing the amount of aryl iododichloride to 1.6 equivalents gave dichloride 6 in 63% yield and 81% ee (see entry 1a, Table 2). Under otherwise identical conditions, but employing the pseudo-enantiomeric catalyst (DHQD)2PHAL, dichloride ent-6 was obtained in 58% yield and 61% ee. As shown in Table 2, the reaction was tolerant of some changes in electronics (entries 1a–e). Very electron-deficient olefins failed to react. Electron-rich cinnamyl substrates underwent rapid dichlorination, but the products were prone to epimerization, chloride elimination, and other decomposition reactions, presumably due to facile benzylic SN1-type reactions. This is not a limitation of the method, but of compound stability; racemic reference samples were similarly labile. Naphthyl substrates reacted in the same manner (entries 2 and 3). Steric congestion was tolerated both on the aryl ring (entry 4) and near the allylic alcohol (entry 5). Importantly, the reaction is stereospecific. Thus, as shown in entry 6, although the efficiency and enantioselectivity of the reaction of cis-cinnamyl alcohol (8) left much to be desired, it proceeded to give the opposite diastereoisomer (9) as compared with the dichlorination of the trans isomer (contrast with entry 1a). Furthermore, the allylic alcohol proved to be a critical substrate feature; masking of this moiety as a TES ether (entry 7) abolished enantioselectivity.

Table 2.

Generality and Scope of Enantioselective Dichlorinationa

| Entry | Substrate | Product | Yield (%)b | ee (%)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a |

1a: X = H (5) 1b: X = Me 1c: X = CF3 1d: X = Cl 1e: X = F |

1a: X = H (6) 1b: X = Me 1c: X = CF3 1d: X = Cl (7) 1e: X = F |

63 | 81 |

| 1b | 65 | 44 | ||

| 1cd | 75 | 48 | ||

| 1d | 81 | 71 | ||

| 1e | 73 | 72 | ||

| 2 |

|

|

84 | 74 |

| 3 |

|

|

66 | 47 |

| 4 |

|

|

63 | 68 |

| 5e |

|

|

90 | 43 |

| 6 |

|

|

35 | 25f |

| 7 |

|

|

32g | <5g |

| 8e |

|

|

48 | 43f,h |

| 9e |

|

|

59 | 54 |

Reactions were performed on 40–50 mg scale using 20 mol % of (DHQ)2PHAL and 1.6 equiv of p-Ph(C6H4)ICl2 in CH2Cl2 (0.05 M) at −78 °C, and run to completion (TLC analysis).

Isolated yield after flash column chromatography.

Determined by chiral HPLC analysis.

Reaction performed at −40 °C.

PhICl2 used in place of p-Ph(C6H4)ICl2.

Absolute configuration not determined.

Incomplete reaction. Yield and ee determined after desilylation.

Determined by NMR analysis of the corresponding Mosher ester.

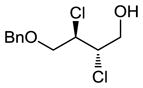

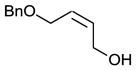

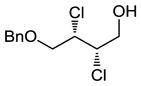

We also investigated the suitability of our reaction conditions on selected non-cinnamyl substrates in order to ensure that we were developing a generally useful catalytic system. We decided to investigate the reactions of monobenzylated cis- and trans-butendiol since differentially protected hydroxyl moieties might be useful for further elaborations of the products.14 The use of p-Ph(C6H4)ICl2 resulted in impractically long reaction times at −78 °C, so the more reactive oxidant PhICl2 was employed instead. Pleasantly, as shown in entries 8 and 9 of Table 2, the reactions proceeded with comparable efficiency and enantioselectivity as those of cinnamyl substrates.

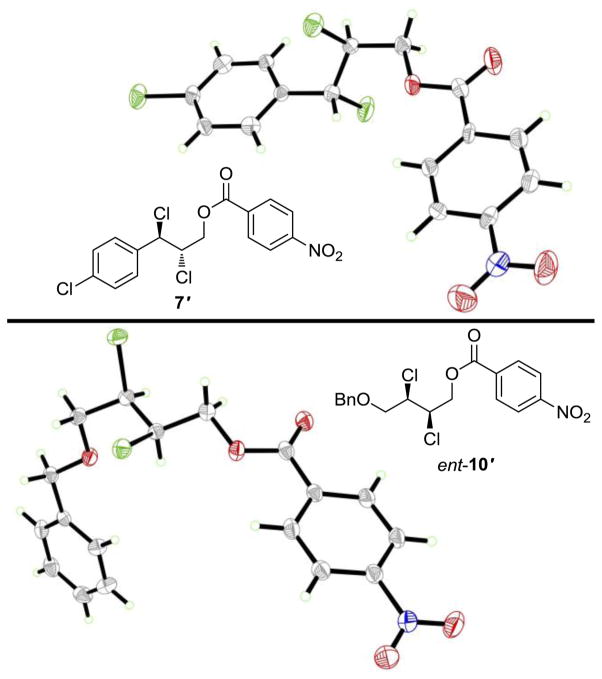

Enantiopure dichlorination products 7 (entry 1d, Table 2) and ent-10 (see entry 9, Table 2) (obtained by preparative HPLC) were converted into p-nitrobenzoate esters 7′ and ent-10′ (Figure 2). X-Ray crystallographic analysis of the p-nitrobenzoates allowed assignment of their absolute configurations. The other di-chlorination products of trans-cinnamyl alcohols were presumed to have the same absolute configuration as 7; however, we currently have no experimental proof of these assignments.

Figure 2.

Molecular structures and ORTEPs of p-nitrobenzoate esters 7′ and ent-10′.

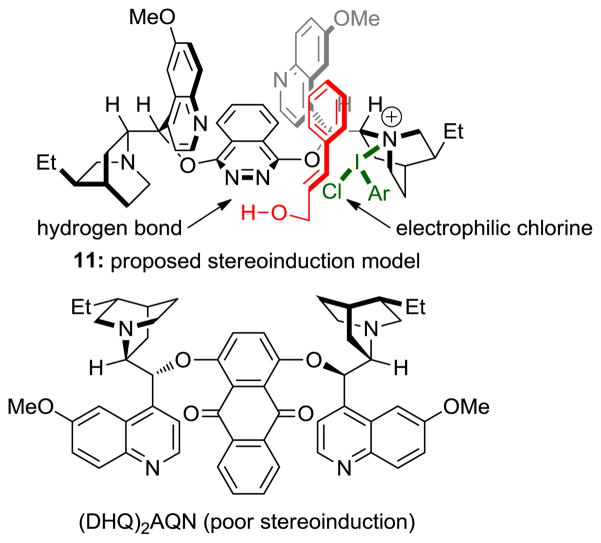

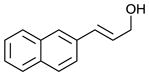

Since the dichlorination is stereospecific, it likely proceeds through the intermediacy of a chloronium species in the manner outlined in Scheme 1. Furthermore, the relative configuration of the products eliminates the possibility of anchimeric assistance in chloronium attack (see 3→4, Scheme 1). The sense of absolute stereoinduction is consistent with preferential chloronium formation on the face of the olefin that would react in a Sharpless asymmetric dihydroxylation employing (DHQ)2PHAL as a ligand. We propose a chlorenium ion transfer from an electrophilic chlorinating reagent generated through attack of the aryl iododichloride by one of the quinuclidine nitrogens of the catalyst (see 11, Figure 3).10,15 Chlorenium delivery might then proceed in a manner analogous to that proposed by Corey and Noe16 for the Sharpless asymmetric dihydroxylation. Since an unmasked allylic alcohol is required, we postulate the presence of a hydrogen bond to one of the pyridazine nitrogens of the catalyst (see 11, Figure 3). Consistent with this hypothesis, (DHQ)2AQN (Figure 3), lacking the pyridazine nitrogens, provides minimal stereoinduction [(10% ee in favor of ent-6, compare with 85% ee in favor of 6 (entry 11, Table 1)]. We acknowledge that the outlined model is speculative; ongoing studies will test and refine this working model.

Figure 3.

Proposed stereoinduction model (11), and the molecular structure of (DHQ)2AQN.

In conclusion, we have developed an enantioselective dichlorination of allylic alcohols employing the dimeric cinchona alkaloid derivative (DHQ)2PHAL [or its pseudoenantiomer (DHQD)2PHAL] and aryl iododichlorides. Further screening of catalyst and iododichloride modifications is under way, and promises to lead to improved enantioselectivity and generality.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. D. H. Huang, L. Pasternack, and R. Chadha for NMR spectroscopic and X-ray crystallographic assistance. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01ES013314), the Skaggs Institute for Research, the National Science Foundation (predoctoral fellowship to N. L. S.), and the Deutsche Akademie der Naturforscher Leopoldina (postdoctoral fellowship to P. M. H.).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures and characterization data for key compounds (CIF, PDF). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org/.

References

- 1.Enantioselective approaches: Julia S, Ginebreda A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1979;20:2171.Adam W, Mock-Knoblauch C, Saha-Möller CR, Herderich M. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:9685.Snyder SA, Tang ZY, Gupta R. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:5744. doi: 10.1021/ja9014716.Snyder SA, Treitler DS, Brucks AP. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:14303. doi: 10.1021/ja106813s.Diastereospecific approaches: Iranpoor N, Firouzabadi H, Azadi R, Ebrahimzadeh F. Can J Chem. 2006;84:69.Yoshimitsu T, Fukumoto N, Tanaka T. J Org Chem. 2009;74:696. doi: 10.1021/jo802093d.Denton RM, Tang X, Przeslak A. Org Lett. 2010;12:4678. doi: 10.1021/ol102010h.Diastereoselective approach: Shibuya GM, Kanady JS, Vanderwal CD. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:12514. doi: 10.1021/ja804167v.

- 2.(a) Gribble GW. Acc Chem Res. 1998;31:141. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kladi M, Vagias C, Roussis V. Phytochem Rev. 2004;3:337. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Elovson J, Vagelos PR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1969;62:957. doi: 10.1073/pnas.62.3.957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Elovson PR, Vagelos PR. Biochemistry. 1970;9:3110. doi: 10.1021/bi00818a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Haines TH, Pousada M, Stern B, Mayers GL. Biochem J. 1969;113:565. doi: 10.1042/bj1130565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ciminiello P, Fattorusso E, Forino M, Di Rosa M, Ianaro A, Poletti R. J Org Chem. 2001;66:578. doi: 10.1021/jo001437s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mooney CL, Haines TH. Biochemistry. 1973;12:4469. doi: 10.1021/bi00746a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ciminiello P, Dell’Aversano C, Fattorusso E, Forino M, Magno S, Di Rosa M, Ianaro A, Poletti R. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:13114. doi: 10.1021/ja0207347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Nilewski C, Geisser RW, Carreira EM. Nature. 2009;457:573. doi: 10.1038/nature07734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bedke DK, Shibuya GM, Pereira A, Gerwick WH, Haines TH, Vanderwal CD. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:7570. doi: 10.1021/ja902138w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Bedke DK, Shibuya GM, Pereira AR, Gerwick WH, Vanderwal CD. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:2542. doi: 10.1021/ja910809c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Yoshimitsu T, Fukumoto N, Nakatani R, Kojima N, Tanaka T. J Org Chem. 2010;75:5425. doi: 10.1021/jo100534d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Umezawa T, Shibata M, Kaneko K, Okino T, Matsuda F. Org Lett. 2011;13:904. doi: 10.1021/ol102882a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Yoshimitsu T, Nakatani R, Kobayashi A, Tanaka T. Org Lett. 2011;13:908. doi: 10.1021/ol1029518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Whitehead DC, Yousefi R, Jaganathan A, Borhan B. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:3298. doi: 10.1021/ja100502f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yousefi R, Whitehead DC, Mueller JM, Staples RJ, Borhan B. Org Lett. 2011;13:608. doi: 10.1021/ol102850m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Denmark SE, Burk MT, Hoover AJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:1232. doi: 10.1021/ja909965h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang W, Xu H, Xu H, Tang W. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:3832. doi: 10.1021/ja8099008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Brochu MP, Brown SP, MacMillan DWC. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:4108. doi: 10.1021/ja049562z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Halland N, Braunton A, Bachmann S, Marigo M, Jørgensen KA. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:4790. doi: 10.1021/ja049231m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Amatore M, Beeson TD, Brown SP, MacMillan DWC. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2009;48:5121. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colby Davie EA, Mennen SM, Xu Y, Miller SJ. Chem Rev. 2007;107:5759. doi: 10.1021/cr068377w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Tommaso M, Hiemstra H. Synthesis. 2010:1229. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wack H, Taggi AE, Hafez AM, Drury WJ, III, Lectka T. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:1531. doi: 10.1021/ja005791j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) France S, Wack H, Taggi AE, Hafez AM, Wagerle TR, Shah MH, Dusich CL, Lectka T. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:4245. doi: 10.1021/ja039046t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Bartoli G, Bosco M, Carlone A, Locatelli M, Melchiorre P, Sambra L. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2005;44:6219. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.β,γ-Dichloroalcohols are amenable to Dess–Martin oxidation and elaboration of the resulting aldehyde without loss of configurational stability.7d

- 15.Denmark SE, Beutner GL. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2008;47:1560. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Corey EJ, Noe MC. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:12579. [Google Scholar]; (b) Corey EJ, Noe MC. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:319. [Google Scholar]; (c) Corey EJ, Noe MC. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:11038. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.