Abstract

This paper reviews factors associated with uptake of risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy by women at increased hereditary risk for ovarian cancer, as well as quality of life issues following surgery. Forty one research studies identified through PubMed and PsychInfo met inclusion criteria. Older age, having had children, a family history of ovarian cancer, a personal history of breast cancer, prophylactic mastectomy, and BRCA1/2 mutation carrier status increase the likelihood of undergoing surgery. Psychosocial variables predictive of surgery uptake include greater perceived risk of ovarian cancer and cancer-related anxiety. Most women report satisfaction with their decision to undergo surgery and both lower perceived ovarian cancer risk and less cancer-related anxiety as benefits. Hormonal deprivation is the main disadvantage reported, particularly by premenopausal women who are not on hormonal replacement therapy (HRT). The evidence is mixed regarding satisfaction with the level of information provided prior to surgery, although generally women report receiving insufficient information regarding the pros and cons of HRT. These findings indicate that when designing decision aids, demographic, medical history, and psychosocial variables need to be addressed in order to facilitate quality decision making.

Keywords: ovarian risk, prophylactic oophorectomy, patient decision making, quality of life

Background

Women at increased putative hereditary risk for ovarian cancer are faced with complex information that needs to be cognitively and emotionally processed in order to make a high quality decision about their risk management options 1. The two main options available to women are increased surveillance and the uptake of risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO), that is, the surgical removal of noncancerous ovaries and fallopian tube 2. There is considerable evidence that simply screening for ovarian cancer (testing for CA125 levels and transvaginal ultrasound) is both inefficient (with multiple false positives) and ineffective (the majority of screen-detected cases are diagnosed at a late stage) 2. RRSO is the alternative approach and has increasingly been shown to be an efficient and effective strategy for reducing cancer risk 2. The guidelines for ovarian cancer risk management now recommend RRSO at the completion of childbearing or by age 35–40 3. For premenopausal women who test BRCA1/2 positive, RRSO has been associated with an 85–90% reduction in ovarian cancer risk and with a 50–68% reduction in breast cancer risk, provided the surgery is performed before the age of 50 4,5,6 for reviews see 7,8.

Patients considering RRSO must also weigh the potential disadvantages of the procedure, including the risks associated with surgery, the effects of hormonal deprivation, and the residual breast, ovarian, and peritoneal cancer risk after removal of the ovaries 2,4,9,10,11 (see Table 1). The risks associated with hormonal deprivation are reportedly higher for women who undertake RRSO before the age of 45 and some premenopausal women take hormone replacement therapy (HRT) in order to reduce these risks 12,13.

Table 1.

Advantages and Disadvantages of RRSO versus Surveillance

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |

|---|---|---|

| RRSO | Most effective form of ovarian cancer risk reduction | Risks associated with the surgical procedure |

| Associated with reduction in breast cancer risk, if performed prior to menopause | Adverse effects of hormonal deprivation (sudden onset of menopausal symptoms, increased risk of osteoporosis, increased risk of metabolic syndrome) | |

| Residual breast, ovarian and peritoneal cancer risk | ||

| Concern about adverse effects on sexuality | ||

| Concern that HRT may increase breast cancer risk, and thus reverse the beneficial effects of the surgery on breast cancer risk | ||

| Surveillance | Noninvasive | Multiple false positives |

| May reduce cancer mortality | Majority of detected cases are diagnosed at late stage | |

| Does not reduce risk of ovarian cancer | ||

| Adherence issues |

The percentage of women who opt for surgery varies considerably across studies 14,15,16,17 (Table 2) and reflects the heterogeneity of samples across studies with respect to the influence of specific demographic, medical, and psychosocial variables on the decision-making process regarding RRSO. These factors are discussed in detail in the next section. The majority of women who opt for surgery do so within a year after undergoing genetic risk assessment 5,18,19,20,21,22,23,24 although the timing of the surgery seems to be, in part, a function of the participants’ age 25,26,27. In this paper, we review studies that examine the patient factors involved in decisions about whether or not to undergo RRSO as well as the impact of that decision on quality of life (QOL) after surgery. We searched PubMed and PsychInfo to identify relevant articles published in English between 2000 and March 2010. The following search terms were combined: prophylactic oophorectomy, preventive oophorectomy, decision making, predictors, and quality of life. Additional sources of articles were references cited in identified papers. Studies were included if they were based on women at high or moderate risk due to a family history of ovarian cancer and if the findings focused on: 1. predictors of RRSO or 2. QOL issues following RRSO. We excluded abstracts of presentations, book chapters, and studies that focused exclusively on self-reported attitudes and intentions to undergo surgery. Regarding factors associated with RRSO uptake, we examined 24 empirical studies and we report only statistically significant findings. Regarding QOL we included 13 quantitative studies. In addition, we report information from four qualitative studies 28,29,30,31.

Table 2.

Studies Reporting Significant Predictors of the use of RRSO

| Study | Study Population | Percent who had RRSO |

Follow-up | Predictors/ Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

NA | NA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

NA | NA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

‘+’: positive effect and ‘−’, negative effect

BC: personal history of breast cancer

RRM: risk reducing mastectomy

CH: has at least one child

FH: family history of ovarian cancer

BM: bilateral mastectomy

BSO: bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy

OCP: use of oral contraceptive pills

On the Horizon

Factors associated with RRSO uptake

A number of predictors and correlates of RRSO have been identified (Table 2). In terms of demographic variables, both prospective and retrospective studies show that older women and women who have children are more likely to undergo surgery 20,32,33,34,35,36–38 (Table 2). Indeed, if one compares uptake rates of RRSO across similar age groups, the differences across studies are not as pronounced (Table 2). Presumably younger women are less likely to have completed their childbearing and are more concerned about their menopausal status and that may be why younger age and not having had children are associated with delaying surgery among mutation carriers 18,27,26. This is not surprising since premenopausal women who undergo surgery (as opposed to surveillance) have to deal with the sudden onset of menopause, which is not only associated with infertility but also with medical and psychological symptoms 39. Finally, less educated women are more likely to undergo surgery 19,40. A possible explanation for this finding is that less educated women prefer a more definitive solution (surgery) in order to gain a higher sense of control28, 41.

Among medical correlates of RRSO uptake, prospective and retrospective studies have found that family history of ovarian cancer 22,41,27,36,42,43 and personal history of breast cancer 16,18,20,34,21,44,45 are associated with higher rates of RRSO (Table 2). In addition, carriers of a BRCA1/2 mutation 19,37,33,34,38,42 are more likely to have RRSO, with several recent studies showing that rates are highest among women with a BRCA1 mutation 26, 43. Prophylactic surgery is more likely to appeal to women who want to decrease uncertainty and maintain a high sense of control over their lives 29. Thus women who opt for risk reducing mastectomy (RRM) choose to undergo RRSO as well 18,33,34,44,46.

Psychosocial factors, both cognitive and affective, are also predictors of RRSO uptake 22,30,32,40,44 (Table 2). Among cognitive factors, the importance of perceived risk is highlighted in one study where both baseline perceived risk and perceived risk after receipt of a genetic test result (positive, negative and uninformative) were explored as predictors of surgery among familial high risk women participating in genetic testing 22. It was the former that predicted RRSO uptake, indicating that pre-existing notions about personal risk continue to influence one’s decisions, even after receipt of genetic counseling and testing feedback. This is an important issue given that women tend to overestimate their perceived risk for breast and ovarian cancer 8,47. Other predictive factors include personal values and beliefs, such as perceiving one’s personal health as poor, viewing ovarian cancer as an incurable disease, believing that surgery is beneficial, and believing that surgery will provide a greater sense of certainty about controlling one’s ovarian cancer risk 40. In addition, in a qualitative study, the majority of women reported their sense of obligation to their family to manage their personal cancer risk as a reason for undergoing RRSO 30. Affective factors, in the form of worry and intrusive ideation, also play a significant role in decision making 32,40. For example, in a retrospective study, women rated both risk-reduction for ovarian cancer and reduction of cancer worry as important reasons for undergoing surgery, but it was cancer worry that uniquely differentiated the women who underwent surgery from those who relied on surveillance 32. Similarly, in a qualitative study, many women who had witnessed a relative die from ovarian cancer were convinced to have surgery 30. In contrast, fear of surgery was associated with the decision to forego RRSO 30.

RRSO and QOL

The effect of RRSO on QOL has been examined in a few studies. Although the findings are not universal 48, women who undergo RRSO report positive changes following surgery, such as lower perceived risk about ovarian cancer (particularly among younger women), less impact of cancer worry on their daily functioning, less anxiety about developing ovarian cancer 8,33,36,39,47,49,50 and a higher sense of control over their lives 29. Qualitative studies have confirmed that the reduction of worry is a major benefit of the surgery and many women reported feeling content that they have fulfilled their family obligations as a benefit 28. Long-term QOL seems to be unaffected 51,33,47,9,45 as women may be adjusting their QOL expectations to take into account the physical changes that result from hormonal deprivation, a cognitive process termed response shift 52. The overwhelming majority of women are satisfied with their decision to undergo surgery (86.4–97%) 33, 36 and report that RRSO had minimal impact on their lives (93%) 29 (Table 2). In a qualitative study, some premenopausal women who took HRT felt more conflicted about their decision to undergo RRSO and expressed guilt about their inability to tolerate the symptoms associated with menopause, particularly when their physician was not committed to the surgery 29.

The majority of women report that RRSO did not have a negative impact on their sense of femininity, presumably because there is no external bodily change 45. In a qualitative study, only a minority reported that they felt older and less feminine following surgery 28. However, both prospective and retrospective studies comparing women who had RRSO with women who relied on surveillance for risk reduction show that those who underwent RRSO reported an increased number of symptoms, such as hot flashes, vaginal dryness, a reduction in sexual interest, a decrease in pleasure and satisfaction with sexual activity, and painful intercourse 33,34,45 particularly among women who were not taking HRT 33,34,50. Most of these symptoms appear to subside with time elapsed since surgery, although the impact of surgery on sexual discomfort 9 and perceived health50 seems to be greater in younger women. Even so, a small number of quantitative 50,48 and qualitative 29,30,31 studies identify a subset of women for whom distress is high after surgery.

The findings are contradictory regarding satisfaction with the information provided prior to the procedure, with some women reporting that they felt that they were fully informed and have participated in the decision process 47, while others report that they would have preferred to have had more information 41. Several qualitative studies reported that after the surgery, many women felt they had inadequate information to make decisions regarding HRT 28,29,31, an important QOL issue for those who are premenopausal 11,12,53.

Decision aids

Because of the complexity of the information that needs to be conveyed to women to enable them to make informed decisions that are consistent with their values, studies have begun to explore the role of decision aids 19,23. Most decision aids aim to provide patients with medical information and help them to systematically integrate that information with their personal values in order to reach a quality decision, consistent with their personal preferences 54. Although helpful, these tools do not take full account of the affective states of women that interact with their cognitive states to influence decision making 54,55,56. One randomized study 23 examined the impact of an intervention aimed at maximizing information processing and promoting informed and deliberate, value-based, decision making among women who had received a positive genetic test result. Although the intervention had no effect on their choice, women who had not had surgery at the time of questioning and who had received the intervention had stronger treatment preferences and experienced less decision uncertainty van 23. In a second randomized controlled study, the intervention was administered prior to the receipt of the test result and was designed to facilitate cognitive and affective processing of risk information provided 19. Over four times as many women underwent prophylactic surgery in the intervention group as in the control group (which received provision of general health information) 19. To the extent that early adoption of risk-reduction strategies, such as RRSO, has a significant impact on lowering medical morbidity, interventions that help women fully process the pros and cons of different strategies may be useful in enhancing decision making.

Conclusions

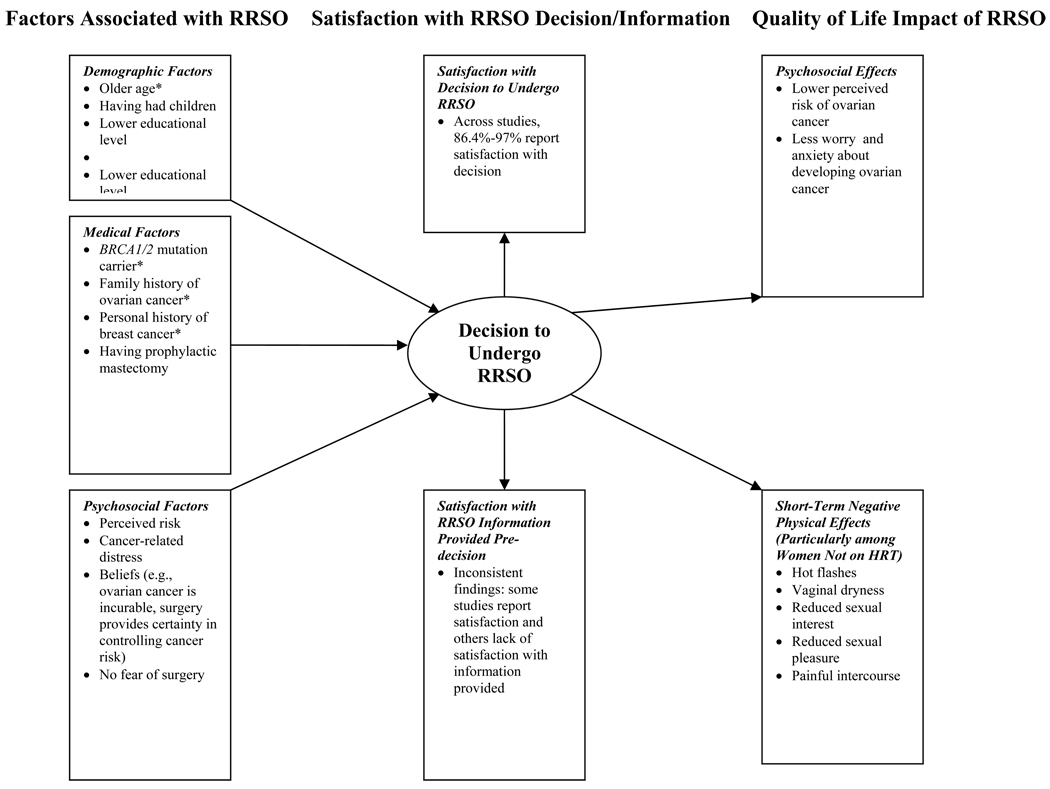

A number of factors have been identified that are positively associated with RRSO uptake. (Figure 1) These include demographic variables (older age, having had children, lower educational level), medical variables (BRCA mutation carrier status, family history of ovarian cancer, personal history of breast cancer, having undergone RRM), and psychosocial variables (e.g., greater perceived ovarian cancer risk, elevated cancer-related distress). (Table 2) Post-surgery, the majority of women are satisfied with their decision to undergo RRSO and report positive QOL-related changes, including reduced perceived ovarian cancer risk, reduced cancer-related distress, and an increased sense of control 36, 47, 50. (Figure 1) Women who report the most surgery-related problems (e.g.; impact of surgery on sexual activity and hot flashes) were for the most part premenopausal at the time of the surgery and did not take HRT 34, 50.

Figure 1.

Factors associated with RRSO uptake, satisfaction with RRSO decision and pre-decision information, and QOL impact of RRSO. Findings marked with an asterisk (*) have strong support in the literature based on number of studies (≥5) and aggregate sample size (≥1000).

The evidence is contradictory regarding level of satisfaction with the information provided prior to surgery and generally women feel inadequately supported with regard to their decision concerning HRT47. (Figure 1) Two randomized studies evaluated the impact of interventions on decision making and found that interventions have positive effects on the quality of decision-making19, 23. In the future it will be important to design decision aids that adequately address the cognitive-emotional sequellae of RRSO, particularly for the subset of women who remain distressed regarding their cancer risk following the surgery 48, 50.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH grants RC1 CA 145063-01, R01 CA104979, PO1CA57586, P30 CA006927, the Department of Defense grants DAMD 17-01-1-0238, DAMD 17-02-1-0382, and DAMD17-01-1-0238, LAF 3600101, and NIHGRI grant R01 HGO11766. We are indebted to Mary Anne Ryan as well as the Fox Chase Cancer Behavioral Research Core Facility.

Contributor Information

Suzanne M. Miller, Professor, Psychosocial and Biobehavioral Medicine Program, Fox Chase Cancer Center

Pagona Roussi, Associate Professor, Psychology Department, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece

Mary B. Daly, Professor and Chair, Medical Oncology, Department of Clinical Genetics, Fox Chase Cancer Center

John Scarpato, Project Manager, Psychosocial and Biobehavioral Medicine Program, Fox Chase Cancer Center

References

- 1.Miller S, McDaniel S, Rolland J, Feetham S, editors. Individuals, families and the new era of genetics: Biopsychosocial perspectives. New York: Norton Publications; 2006. eds. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Domchek S, Rebbeck T. Prophylactic oophorectomy in women at increased cancer risk. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;19:27–30. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e32801195da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daly M, Axilbund J, Crawford B, et al. Genetic/Familial High Risk Assessment: Breast and Ovarian. J Natl Compre Canc Netw. 2010;8:562–594. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finch A, Beiner M, Lubinski J, et al. Salpingo-oophorectomy and the risk of Ovarian, Fallopian Tube, and Peritoneal Cancers in Women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. JAMA. 2006;296:185–192. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kauff N, Satagopan J, Robson M, et al. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA 2 mutation. New Engl J Med. 2002;346:1609–1615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurian A BM, S SKP. Survival analysis of cancer risk reduction strategies for BRCA 1/2 mutation carriers. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:222–231. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.7991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rebbeck T, Kauff N, Domchek S. Meta-analysis of risk reduction estimates associated with risk-reducing Salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer. 2009;101:80–87. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Metcalfe K. Oophorectomy for breast cancer prevention in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. Women Health (Lond Engl) 2009;5:63–68. doi: 10.2217/17455057.5.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michelsen TM, Dorum A, Dahl AA. A controlled study of mental distress and somatic complaints after risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in women at risk for hereditary breast ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;113:128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rivera C, Grossardt B, Rhodes D, et al. Increased cardiovascular mortality after bilateral oophorectomy. Menopause. 2009;16:15–23. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31818888f7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Menopause L, Gostout B, Grossardt B, Rocca W. Prophylactic oophorectomy in premenopausal women and long term health. Menopause. 2008;14:111–116. doi: 10.1258/mi.2008.008016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rebbeck T, Friebel T, Wagner T, et al. Effect of short term hormone replacement therapy on breast cancer risk reduction after bilateral prophylactic oophorectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: the PROSE Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7804–7810. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.8151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gabriel C, Tigges-Cardwell J, Stopfer J, et al. Use of total abdominal hysterectomy and hormone replacement therapy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers undergoing risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy. Fam Cancer. 2009;8:23–28. doi: 10.1007/s10689-008-9208-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeLeeuw J, van Vliet M, Ausems M. Predictors of choosing life-long screening or prophylactic surgery in women at high and moderate risk for breast and ovarian cancer. Fam Cancer. 2008;7:347–359. doi: 10.1007/s10689-008-9189-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Howard A, Balneaves L, Bottorf J. Women's Decision making about risk-reducing strategies in the context of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer: A systematic review. J Genet Couns. 2009;18:578–597. doi: 10.1007/s10897-009-9245-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Metcalfe K, Birenbaum-Carmeli D, Lubinski J, et al. Cancer genetics: international variation in rates of uptake of preventive options in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:2017–2022. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wainberg D, Husted J. Utilization of screening and preventive surgery among unaffected carriers of a BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutation. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:1989–1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beattie M, Crawford B, Feng L, et al. Update, Time course, and Predictors of Risk-reducing surgeries in BRCA carriers. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2009;13:51–56. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2008.0067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller S, Roussi P, Daly M, et al. Enhanced counseling for women undergoing BRCA 1/2 testing: impact on subsequent decision making about risk reduction behaviors. Health Educ Behav. 2005;32:654–667. doi: 10.1177/1090198105278758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scheuer L, Kauff N, Robson M, et al. Outcome of Preventive Surgery and Screening for Breast and ovarian cancer in BRCA Mutation carriers. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1260–1268. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.5.1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmeler K, Sun C, Bodurka D, et al. Prophylactic Bilateral Salpingo-Oophorectomy compared with surveillance in women with BRCA mutations. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:515–520. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000228959.30577.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwartz M, Kaufman E, Peshkin B, et al. Bilateral Prophylactic Oophorectomy and Ovarian cancer following BRCA1/BRCA2 Mutation Testing. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4034–4041. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Roosmalen M, Stalmeier P, Verhoef L, et al. Randomized Trial of a Shared-decision making intervention consisting of trade-offs and individualized treatment information for BRCA 1/2 mutation carriers. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3293–3301. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meijers-Heijboer H, Brekelmans C, Menke-Pluymers M, et al. Use of Genetic Testing and Prophylactic Mastectomy and Oophorectomy in Women with Breast or Ovarian Cancer from families with a BRCA1 or BRCA 2 mutation. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1675–1681. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skytte A-B, Gerdes A-M, Andersen M, et al. Risk-reducing mastectomy and salpingo-oophorectomy in unaffected BRCA mutation carriers: uptake and timing. Clin Genet. 2010;77:342–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evans DG, Lalloo F, Ashcroft L, et al. Uptake of risk-reducing surgery in unaffected women at high risk of breast and ovarian cancer is risk, age, and time dependent. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2318–2324. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bradbury A, Ibe C, Dignma J, et al. Update and timing of bilateral prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy among BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Genet Med. 2008;10:161–166. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e318163487d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hallowell N, Mackay J, Richards M, Gore M, Jacobs I. High-risk premenopausal women's experiences of undergoing prophylactic oophorectomy: a descriptive study. Genet Test. 2004;8:148–156. doi: 10.1089/gte.2004.8.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meiser B, Tiller K, Gleeson MA, Andrews L, Robertson G, Tucker KM. Psychological impact of prophylactic oophorectomy in women at increased risk for ovarian cancer. Psychooncology. 2000;9:496–503. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200011/12)9:6<496::aid-pon487>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hallowell N, Jacobs I, Richards M, Mackay J, Gore M. Surveillance or surgery? A description of the factors that influence high risk premenopausal women's decisions about prophylactic oophorectomy. J Med Genet. 2001;38:683–691. doi: 10.1136/jmg.38.10.683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hallowell N. A qualitative study of the information needs of high-risk women undergoing prophylactic oophorectomy. Psychooncology. 2000;9:486–495. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200011/12)9:6<486::aid-pon478>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fry A, Rush R, Busby-Earle C, Cull A. Deciding about prophylactic oophorectomy: what is important to women at increased risk of ovarian cancer? Prev Med. 2001;33:578–585. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Madalinska JB, Hollenstein J, Bleiker E, et al. Quality-of-life effects of prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy versus gynecologic screening among women at increased risk of hereditary ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6890–6898. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Madalinska JB, van Beurden M, Bleiker EM, et al. The impact of hormone replacement therapy on menopausal symptoms in younger high-risk women after prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3576–3582. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meijers-Heijboer EJ, Verhoog LC, Brekelmans CT, et al. Presymptomatic DNA testing and prophylactic surgery in families with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. Lancet. 2000;355:2015–2020. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02347-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tiller K, Meiser B, Butow P, et al. Psychological impact of prophylactic oophorectomy in women at increased risk of developing ovarian cancer: a prospective study. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;86:212–219. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2002.6737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Antill Y, Reynolds J, Young M, et al. Risk reducing surgery in women with familial susceptibility for breast and/or ovarian cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:621–628. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kram V, Peretz T, Sagi M. Acceptance of preventive surgeries by Israeli women who had undergone BRCA testing. Fam Cancer. 2006;5:327–335. doi: 10.1007/s10689-006-0002-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benshushan A, Rojansky N, Chaviv M, et al. Climacteric symptoms in women undergoing risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Climacteric. 2009;12:404–409. doi: 10.1080/13697130902780846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Madalinska JB, van Beurden M, Bleiker EM, et al. Predictors of prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy compared with gynecologic screening use in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:301–307. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.4922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Swisher EM, Babb S, Whelan A, Mutch DG, Rader JS. Prophylactic oophorectomy and ovarian cancer surveillance. Patient perceptions and satisfaction. J Reprod Med. 2001;46:87–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Uyei A, Peterson SK, Erlichman J, et al. Association between clinical characteristics and risk-reduction interventions in women who underwent BRCA1 and BRCA2 testing: a single-institution study. Cancer. 2006;107:2745–2751. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Metcalfe KA, Foulkes WD, Kim-Sing C, et al. Family history as a predictor of uptake of cancer preventive procedures by women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. Clin Genet. 2008;73:474–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2008.00988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Metcalfe K, Narod S. Breast cancer prevention in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. Open Med. 2007;1:184–190. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fang CY, Cherry C, Devarajan K, Li T, Malick J, Daly MB. A prospective study of quality of life among women undergoing risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy versus gynecologic screening for ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112:594–600. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.11.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Metcalfe KA, Lubinski J, Ghadirian P, et al. Predictors of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation: the Hereditary Breast Cancer Clinical Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1093–1097. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.6078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Elit L, Esplen MJ, Butler K, Narod S. Quality of life and psychosexual adjustment after prophylactic oophorectomy for a family history of ovarian cancer. Fam Cancer. 2001;1:149–156. doi: 10.1023/a:1021119405814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bresser PJ, Van Gool AR, Seynaeve C, et al. Who is prone to high levels of distress after prophylactic mastectomy and/or salpingo-ovariectomy? Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1641–1645. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Finch A, Metcalfe K, Lui J, et al. Breast and ovarian cancer risk perception after prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy due to an inherited mutation in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene. Clin Genet. 2009;75:220–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2008.01117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Robson M, Hensley M, Barakat R, et al. Quality of life in women at risk for ovarian cancer who have undergone risk-reducing oophorectomy. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;89:281–287. doi: 10.1016/s0090-8258(03)00072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Michelsen TM, Dorum A, Trope CG, Fossa SD, Dahl AA. Fatigue and quality of life after risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in women at increased risk for hereditary breast-ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19:1029–1036. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181a83cd5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sprangers M, Schwartz C, editors. Adaptation to changing health. Response shift in quality of life research: American Psychological Association. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Armstrong K, Schwartz JS, Randall T, Rubin SC, Weber B. Hormone replacement therapy and life expectancy after prophylactic oophorectomy in women with BRCA1/2 mutations: a decision analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1045–1054. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ubel PA, Loewenstein G. The role of decision analysis in informed consent: choosing between intuition and systematicity. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:647–656. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00217-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miller SM, Fang CY, Manne SL, Engstrom PF, Daly MB. Decision making about prophylactic oophorectomy among at-risk women: psychological influences and implications. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;75:406–412. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1999.5611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schwartz MD, Peshkin BN, Tercyak KP, Taylor KL, Valdimarsdottir H. Decision making and decision support for hereditary breast-ovarian cancer susceptibility. Health Psychol. 2005;24:S78–S84. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.4.S78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]