Abstract

Introduction and background

Few financial incentives in the United States encourage coordination across the health and social care systems. Supportive Service Programs (SSPs), operating in Naturally Occurring Retirement Communities (NORCs), attempt to increase access to care and enhance care quality for aging residents. This article presents findings from an evaluation conducted from 2004 to 2006 looking at the feasibility, quality and outcomes of linking health and social services through innovative NORC-SSP and health organization micro-collaborations.

Methods

Four NORC-SSPs participated in the study by finding a health care organization or community-based physicians to collaborate with on addressing health conditions that could benefit from a biopsychosocial approach. Each site focused on a specific population, addressed a specific condition or problem, and created different linkages to address the target problem. Using a case study approach, incorporating both qualitative and quantitative methods, this evaluation sought to answer the following two primary questions: 1) Have the participating sites created viable linkages between their organizations that did not exist prior to the study; and, 2) To what extent have the linkages resulted in improvements in clinical and other health and social outcomes?

Results

Findings suggest that immediate outcomes were widely achieved across sites: knowledge of other sector providers’ capabilities and services increased; communication across providers increased; identification of target population increased; and, awareness of risks, symptoms and health seeking behaviors among clients/patients increased. Furthermore, intermediate outcomes were also widely achieved: shared care planning, continuity of care, disease management and self care among clients improved. Evidence of improvements in distal outcomes was also found.

Discussion

Using simple, familiar and relatively low-tech approaches to sharing critical patient information among collaborating organizations, inter-sector linkages were successfully established at all four sites. Seven critical success factors emerged that increase the likelihood that linkages will be implemented, effective and sustained: 1) careful goal selection; 2) meaningful collaboration; 3) appropriate role for patients/clients; 4) realistic interventions; 5) realistic expectations for implementation environment; 6) continuous focus on outcomes; and, 7) stable leadership. Focused, micro-level collaborations have the potential to improve care, increasing the chance that organizations will undertake such endeavors.

Keywords: collaboration, linkage, aging, chronic illness, community-based

Introduction and background

Providing care for elderly individuals with chronic illnesses in the community requires a model of service delivery that takes into account both physical health and social health needs. However, packaging care in this way does not fit into existing service or reimbursement structures in the United States, and there are few financial incentives that encourage coordination. In fact, funding and reimbursement systems tend to discourage cross setting integration [1, 2]. While there are a small number of innovative programs that have pooled resources and coordinated care for discrete populations across service systems (e.g. Social HMO, PACE, MMIP, PROCARE), they tend to be highly complex, limited in scope, costly, and large scale evaluations have found mixed results. Indeed, several of these programs are no longer in operation—or exist in an extremely limited fashion—due to their inability to show positive outcomes and/or due to their poor cost-benefit ratio [3]. Furthermore, most social service and health care managers are not trained in developing effective multidisciplinary programs with other types of providers. The organizations within which they work tend to be departmentalized and fragmented along functional lines. Lack of coordinated care can negatively affect access to high quality, appropriate care, putting at risk seniors’ physical and mental health, quality of life, and ability to stay in the community.

The rise of NORC-SSPs

About 20 years ago, social service providers in New York State developed a model of care aimed at overcoming service fragmentation and its potential risks for community dwelling elders [4]. The first step towards the development of a new model of care was the realization that there were age-integrated housing developments and neighborhoods throughout New York City where large numbers of elderly persons were residing and in need of supports and services where they were living. Naturally Occurring Retirement Communities (NORC) became the natural home for Supportive Service Programs (SSP). The first NORC-SSP was established in 1986 at Penn South Houses in New York City. In 1995, New York State endorsed the model by providing funding to create 14 NORC-SSPs; New York City followed suit in 1999. Today 54 NORC-SSPs operate in New York State with 43 of them in New York City. Together these programs serve multi-age communities in which more than 67,000 seniors live [5, 6]. Over the past 10 years, the NORC program concept has spread to more than 40 communities in 25 other states through the use of federal earmark dollars, and several states are piloting state-wide initiatives. NORCs have evolved from primarily vertical arrangements (i.e. in high-rise, city-based apartment buildings) to both vertical and horizontal arrangements (the latter referring to suburban-based, single family homes). In October 2009, Community Innovations for Aging-in-Place national demonstration began under the auspices of the United States Department of Health and Human Services – Administration on Aging to test models and approaches, including a strong emphasis on the NORC program concept.

NORC-SSPs unite housing entities, health and social service providers, residents and other community stakeholders, government, and philanthropic organizations to provide a wide range of services, early interventions, and meaningful activities for seniors in communities where they live. The NORC-SSP model represents a significant departure from the current service delivery system based on functional deficits. From program development to the definition of client, the model expands the role of older people in their community from recipients of services to active participants in shaping their community as ‘good places to grow old’ [4]. The model also assumes quite different approaches to defining and therefore financing services, and to collaborations among health and social service providers.

New York NORC-SSPs are distinguished by the following hallmarks: 1) They are based on community-identified challenges to aging-in-place; 2) Residents themselves play a vital role in the development and operations of NORC-SSPs; 3) They are financed through public-private partnerships that combine revenues and in-kind supports; 4) Their programs promote independence and healthy aging by engaging seniors before a crisis and responding to their changing needs over time; and, 5) Eligibility for services and programs is based on age and residence in the NORC, rather than on functional deficits or economic status, and the mix of services available is resident-specific, not program specific.

Integrating health and social health care in NORC-SSPs

All NORC-SSPs provide social work services; indeed, in most NORC-SSPs in New York City, the lead agency is a social services agency. Most NORC-SSPs in the city have a health care partner as well; the partner may be a certified home health agency, nursing home, or hospital. Educational and recreational activities and volunteer opportunities are diverse and designed to engage as many community residents as possible. Although organized and managed by the professional staff, many classes or activities are led by the seniors themselves. Because success depends on the extent to which a NORC-SSP reflects the strengths, interests, and aspirations of community residents, thorough assessment, extensive and ongoing outreach, and the ability to understand and adapt to changes in the community over time are essential.

New York’s NORC-SSPs have developed various governance structures in order to manage the complex partnerships of housing corporations, social service agencies, health care providers, government agencies, and the residents themselves. NORC-SSPs work hard to make the collaboration among these diverse partners viable; strong leadership is key, as is an ability to redefine institutional boundaries and relationships. Despite ongoing growing pains, the New York NORC-SSP experience has demonstrated that it can be done: public programs, service delivery organizations, and communities themselves can come together to create and operate totally new forms of senior services, organized around the seniors and their communities, which can make a positive and palpable difference in individual lives [4].

There is a growing body of literature that recognizes the importance—and potential—of health and social service organizations working together to improve health outcomes in communities [7–13]. The majority of well-known community health improvement programs have targeted a single disease and have been organized as ‘top-down’ initiatives, often with a university-based research group leading the effort [14]. While the logic of implementing health promotion interventions within the community is clear, evidence demonstrating impact on targeted health outcomes is sparse. Health improvement through community-based interventions remains a challenge and calls for new theories, models and methods [14].

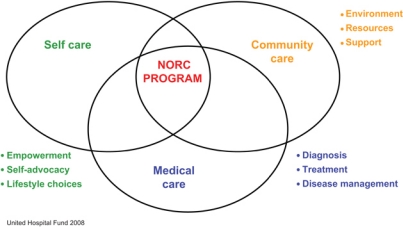

The NORC-SSP model redefines the classic chronic care approach by recognizing that medical care, community care and self care are equally important components of comprehensive chronic care management. Departing from the classic institution-centric model, this Community Chronic Care Model (see Figure 1) underscores the critical role of the NORC-SSP in integrating the essential components of successful aging-in-place for chronically ill individuals residing in the community.

Figure 1.

Community chronic care model.

The NORC-SSP Linkage initiative

In 2002, two New York City-based funders, the United Hospital Fund1 and The New York Community Trust2 initiated a demonstration project, termed the NORC-SSP Linkage Project, which included coordinated grantmaking to five project sites to design and implement collaborative approaches3 to information sharing, tracking, and producing outcomes for community-dwelling elders. The grants also allowed for the provision of technical assistance to grantees by Fund staff, and a robust evaluation of the individual sites and the project as a whole. The Linkage Project was developed with the recognition that integrating health and social services is both complex and necessary to promote successful aging-in-place. By design, NORC-SSPs attempt to increase access to care and enhance care quality for aging residents through a complex web of services that include community outreach, needs assessment, service coordination, service provision and ongoing client monitoring. Given that the overarching goal of the NORC-SSP is to enable residents to ‘successfully age in place,’ a focus on both social services and population-based health care is essential. Since their inception in 1986, NORC-SSPs have partnered with local health care providers to address both individual and community-wide health issues. However, while NORC-SSPs create greater collaboration between social service and health providers, each of these sectors continue to operate along functional lines, and on a reactive basis. Indeed, the realization that health and social service providers were essentially speaking ‘at’ each other rather than ‘with’ each other about managing chronic illness led the funders to undertake the Linkage initiative.

The integration of health and social services is therefore defined more broadly in the Linkage project than in traditional NORC-SSP-health care partnerships. Health and social services are not seen as supplemental to each other nor connected merely by referral channels, but rather defined by multidisciplinary needs assessment, targeted program planning, care planning and management, and ongoing follow-up. Although the concept of service integration is more comprehensive in the Linkage project, the vehicle is less intense than a ‘partnership’ in the formal sense. The goal of The Linkage Project was to foster the development and testing of new models of collaborative and coordinated problem-solving, models that involve ‘micro-collaborations’ using simple, familiar and relatively low-tech approaches to sharing critical patient information among collaborating organizations.

Participating NORC-SSPs and health care providers worked together to identify health conditions in the community that could benefit from more systematic communication and information exchange as well as targeted programming. Targeted conditions were: falls; discharge planning and medication management; depression; and diabetes. Gaps in services were identified and discrete mechanisms or strategies—that is, linkages—were designed to fill those gaps. A central goal was for the linkages to become part of routine practice at each collaborating organization. Rather than dedicating a staff member to deal with individual health problems as they arise, the Linkage Project defines health as multi-faceted and focuses on population-based approaches to prevention, health promotion and multidisciplinary care planning.

Methods

Conceptual framework for the NORC-Health Care Linkage evaluation

Evaluations of initiatives implemented across multiple settings, each with different partnership relationships, different population targets and different interventions are highly complex. One major problem in evaluating multi-site community-based projects is that the overall goals and objectives are difficult to conceptualize. While individual projects may claim to share a common vision, they function in very different environments and often approach the same problem in different ways [15].

There are many theories that help explain collaborative action and the factors likely to influence it. They come from the disciplines of organizational behavior, sociology, political science and economics. However, most classical theories do not complement each other well, and community-based health care initiatives require theoretical guidance that takes into account the complexities of creating partnerships in addition to the challenges of explaining health behavior change within a highly complex and variable external environment.

Theories of action (TOAs) explain how a program is expected to get from conditions at baseline to a desired future; thereby bridging strategic planning and evaluation [15]. Clarifying underlying assumptions can help to articulate and operationalize hypotheses, research questions, variables of interest and appropriate data collection instrument. TOAs can also help evaluators better understand when expected short-term and long-term outcomes might be observable by examining the order and various levels of anticipated effects [15].

The most effective TOAs are co-generated by evaluators and partnership representatives. Working collaboratively also fosters ownership to the components of the theory and enables individual organizations to develop their own theories. Since the purpose of evaluation of complex community initiatives is to facilitate their improvement and effectiveness [16], programs must be guided by more specific ‘treatment theories’ that will explain how interventions will reach the target population in sufficient ‘dosage’ to be detectable [14]. Treatment theories attempt to explain how inputs translate into outputs; how programs plan on producing anticipated effects.

Moving from the abstract identification of an overall vision and ultimate program goals to the nuts and bolts of designing and implementing interventions that will enable those goals to be achieved requires linking theory to practice. While TOAs are more concrete than classical theories of organizational behavior or social change, they still need to have their components defined and linked to realistic indicators, measures and timeframes. The logic model provides a tool for conceptualizing the relationships between short-term outcomes produced by programs, intermediate system impacts and long-term community goals [17, 18]. The logic model is described as a logical series of statements linking a condition(s) in the community, the activities that will be employed to address the condition(s), short-term outcomes resulting from activities and long-term impacts likely to occur as multiple outcomes are achieved [19].

The logic model treats each partnership as a separate case study recognizing that the community-driven approach results in a wide range of goals and objectives and program outcomes [18]. The value of the logic model is its ability to consider connections between conditions, activities, outcomes and impacts [19]. Conditions should reflect concerns of local populations that can be realistically addressed through the interventions defined in the activities component. Similarly, activities should lead in a logical sequence to short-term outcomes and such outcomes should contribute to the achievement of longer-term system impacts and/or community goals. Looking at outcomes in this hierarchical way provides a framework for the Linkage evaluation.

Each of the participating Linkage sites developed a TOA and a Logic Model. Empirical basis for testing effectiveness relied primarily on case methodology, although other qualitative approaches were utilized to overcome the bias inherent in any one method, and to increase validity because different methods highlight different aspects of the experience [16]. The logic model enables us to look at individual sites and collective experiences and compare outcomes across common dimensions [20].

The Linkage evaluation followed the lead of other multi-site, community-based evaluations [13–15, 20] in recognizing the importance of changing organizational behavior as a prerequisite for changing client/patient behavior. It was hypothesized that effective service linkages could only occur after the collaborating organizations saw each other as offering essential services that could help them better care for their clients/patients. To realize this value, organizations first needed to know that each other exist, understand what services each provide, how these services fill gaps in care that negatively affect their clients/patients and how the integration of these services could be realistically achieved. Therefore, immediate outcomes, the first level, were specified as those that demonstrate increased awareness about the other sector providers and increased knowledge of the target population; intermediate outcomes, the second level, were specified as those that demonstrate changes in practice and behavior; and, long-term/distal outcomes, the highest level, were specified as those that demonstrate changes in health status. Immediate and intermediate outcomes may cumulatively, but not necessarily directly, lead to changes in more distal outcomes [10].

The evaluation approach offered Linkage sites great flexibility in designing, implementing and evaluating their own interventions, with guidance from the funders and external evaluator. The importance of evidence-based program planning was emphasized from the outset. Sites were encouraged to see the value in tracking their own progress for both accountability purposes and future programming. This innovative initiative aimed to build capacity so the participating sites could continue to apply these new skills long after the funder and external evaluator had gone back to their respective professional homes.

This article presents findings from the evaluation of the demonstration sites’ experience over two years (2004–2006); year 1 involved planning and year 2 implementation of the Linkage interventions. The evaluation looked at the feasibility and quality of linkages, as well as the impact of the linkages on selected care process and clinical outcomes. Using a case study approach, incorporating both qualitative and quantitative methods, this evaluation sought to answer the following two primary questions:

Have the sites created viable linkages between the participating organizations that did not exist prior to the Linkage initiative; and,

To what extent have the linkages resulted in improvements the key variables of interest: knowledge and awareness of partner services and target population; communication among partners; shared care planning; continuity of care; and outcomes of care.

Data collection strategies and instruments

Immediate, intermediate and distal outcomes were tracked using tracking forms, client surveys, stakeholder interviews, chart reviews and periodic site visits. Intensive technical assistance enabled the participating sites to take an active role in data collection and analysis. Comprehensive data guides were produced for each site with specific steps for implementing interventions, tracking progress and collecting data. Using a consensus process, the data guides outlined data sources, responsible parties and timelines.

Participating sites submitted quarterly reports including both a narrative discussion and data on progress. Outcomes tables were constructed for each site per quarter based on these reports and supplemented with additional data generated from other sources (i.e. interviews, site visits). Tables tracking overall progress regarding implementation of activities and outcomes were also compiled.

Three months into the implementation year, and then again at the end of the implementation year, staff involved in the planning and implementation of the Linkage projects at each site—defined as Stakeholders—completed a web-based survey assessing the collaboration. The evaluator conducted site visits and follow-up telephone interviews with program staff at several points throughout the grant period to collect additional information on the process and to provide technical assistance with data tracking, as needed. Process measures, including level of community participation, level of site participation, planning products developed, use of financial and human resources, and services provided were examined.

Description of Linkage participants, theories of action and interventions

The Linkage project supported the efforts of four NORC-SSPs4 operating in New York City, in establishing service linkages with health care providers to improve care. All four sites brought together the NORC-SSP with that community’s key health care provider—hospital, primary care clinic, or voluntary community physicians to collaborate on addressing health conditions that could benefit from a biopsychosocial approach—conditions that require effective co-management of physical, psychosocial and environmental factors. Table 1 describes the four Linkage communities by geographic location, type of housing, number of residents, staffing structure, existing health care partner, and linkage focal point.

Table 1.

Description of funded linkage communities

| NORC-SSP site | NORC community | Staffing | NORC health care partner (existing) | Linkage focal point (new) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mid-Manhattan | A coalition of a public housing complex and a moderate-income cooperative on Manhattan’s Upper West Side where more than 800 of the approximately 3200 residents are seniors. Senior residents are primarily Black and Hispanic (76% combined). NORC-SSP established in 2000 | Two and a half full-time social workers, one full-time nurse | Local hospital | Emergency Department of local hospital partner, and local pharmacies |

| Lower Manhattan | A public housing project on Manhattan’s Lower East Side with 27 buildings, 3000 residents, 860 of whom are seniors. The senior population is diverse: 59% Hispanic; 22% Asian; 14% White; 5% Black. NORC-SSP established in 1993 | Four full-time social workers, one part-time nurse (3 day/week) | Certified home care agency | Local primary care clinic |

| Queens | A moderate income garden apartment cooperative in northeast Queens, home to more than 4000 residents, 1000 of whom are seniors. Senior residents are overwhelmingly White. NORC-SSP established in 2000 | Two full-time social workers, and a 75% time nurse (4 days/week) | Local hospital | Community physicians affiliated with local hospital partner |

| Brooklyn | A large, primarily low-income rental housing complex in an isolated part of southern Brooklyn, with 46 buildings, 14,000 residents, 2700 of whom are seniors. The senior population is diverse: 44% Black; 41% White; 15% Hispanic and a growing Russian population. NORC-SSP established in 2000 | Three full-time social workers, one full-time nurse | Local hospital | Community physicians |

Each Linkage site focused on a specific population, addressed a specific condition or problem, and created different linkages to address the target problem. Focusing on the common goals of increasing access to care, improving continuity of care, and improving care quality and outcomes for community-dwelling elders by integrating health and social services, each Linkage site worked with the funders and evaluator to develop a local theory of action, strategies for creating linkages among select providers, and interventions to test the theories.

Mid-Manhattan site

The Mid-Manhattan site sought to improve emergency room diagnosis, treatment and discharge planning by strengthening relationships between the NORC-SSP, the Emergency Department (ED) at the participating hospital, and local pharmacies. The initial theory behind this linkage was that with immediately available, comprehensive information about medications, ED physicians would be better able to care for seniors in crisis, hospitals would be able to improve the discharge planning process, and the NORC-SSP would be better equipped to support medication compliance after discharge, perhaps preventing inappropriate rehospitalizations.

The Mid-Manhattan NORC-SSP already partnered with the local hospital for the on-site nurse; however, their linkage intervention expanded this limited relationship by initiating an intervention where the hospital emailed5 the NORC-SSP a daily list of discharges from within the NORC catchment area. For the first time the NORC-SSP nurse and social worker would be able to proactively follow-up with all NORC residents that had been seen in the ED. NORC staff could now address the problems that triggered the ED visit, assist with the transition back to the community for those that had been discharged following an inpatient stay, and track health trends within their population for the purposes of planning health related programming and services. The hospital would expand its reach as well. Delayed, absent or poor follow-up post-discharge can lead to inappropriate readmissions to the hospital.

Building upon the ED discharge collaboration, the Mid-Manhattan NORC-SSP reached out to local pharmacies to create and manage an electronic medical record, called MyMeds, that would be shared by the NORC-SSP, the ED and local pharmacies. This intervention was based on a theory of action that said the more providers who know about all the medications a resident is on, the less chance there is for errors and treatment delays and the more likely it will be that the resident will adhere to the treatment regimen and experience positive outcomes.

The NORC-SSP held informal training and education sessions with pharmacies as they came on board about the MyMeds process and purpose. ED physicians were educated about the program during staff meetings. Initially, residents were recruited to enroll in the MyMeds program upon discharge from the ED, although over time additional residents who heard about the program by word of mouth were also enrolled. Medication profiles were created for all enrollees and uploaded at their pharmacy of choice. Enrollees were educated about the purpose of the program and the importance of medication compliance. Bracelets specifying current medications were offered to all enrollees.

Lower Manhattan site

The Lower Manhattan site theorized that if the NORC-SSP worked together with the local primary care center on managing care for Hispanic residents with diabetes, care outcomes would improve. The linkage sought to connect these two organizations through the sharing of information and coordination of efforts. Initially, paper forms with diagnostic, treatment and appointment information were faxed back and forth; over time a more technologically sophisticated approach—a shared, electronic patient database—was established.

The NORC-SSP already partnered with a certified home care agency for the on-site nurse and this new transfer of information would enable her—and the social work staff—to systematically determine who among their residents were being treated for diabetes and how best to help them manage their illness. While the NORC-SSP staff had long been trying to monitor clients with diabetes, they were not always aware of prescribed treatment regimens, dietary restrictions, scheduled follow-up appointments, or how to identify signs of poorly managed symptoms. The shared database would enable NORC-SSP staff to use the health status data entered by the primary care center staff to determine where to focus their efforts (e.g. symptom education, assistance with shopping or transportation, home care referrals for nutrition education, diet planning, glucometer training, medication administration or monitoring).

The primary care center, on the other hand, specialized in diabetes care—indeed it had an ongoing Diabetes Collaborative—but was disconnected from patients as soon as patients left the medical office and therefore limited in how it could intervene in the patient’s day-to-day disease experience and follow-up care. The primary care center-based physicians could use the social status data entered by the NORC-SSP staff to better understand their patients’ living situation, social health needs and economic status, thus enabling a more tailored and comprehensive treatment plan and minimizing the risk of decline associated with poorly managed symptoms among patients with diabetes.6

The NORC-SSP held training and education programs for the primary care center staff in an effort to increase knowledge of partner capabilities and services. To empower seniors to become more active participants in the management of their illness, one-on-one counseling sessions (at the NORC-SSP or in the home) as well as group visits (at the primary care center) were implemented.

Queens site

The Queens site theorized that if the NORC-SSP worked closer with community physicians they could decrease falls among their residents.7 They recognized that each provider had important pieces to the falls prevention puzzle—the NORC-SSP had information on the home and residents’ day-to-day lives, the community physician had information on the residents’ medical conditions and medications. Putting the puzzle pieces together in a proactive, collaborative way was expected to optimize resident care and decrease preventable falls. The Queens site already partnered with the local hospital for the on-site nurse which helped to facilitate the linkage with hospital-affiliated community physicians.

The system of communication used by the Queen site involved the sharing of community-based risk assessment results with community physicians. Home visits to assess the environment for falls risk and to screen for other falls risks (e.g. trigger drugs, dementia) were conducted on all residents. A five-point risk screening tool (age, history of previous falls, use of assistive devices, use of 5+ medications, and ability to ‘get up and go’) identified those in need of a multifactorial assessment and comprehensive, integrated, intervention approach. At risk residents were assessed by NORC-SSP staff using the Hartford Scale Falls Risk Assessment [21], and the score faxed to the resident’s physician in the form of a short and concise consultation letter. The style of the letter was similar to the familiar home health referral letter making it easy for physicians to request specific services from the Queens-based NORC-SSP (including additional information) or make a referral for a physical therapy evaluation, durable medical equipment, home care, or other services. Physicians were able to respond to the letter by checking off desired actions, signing his or her name for orders and faxing back the letter. The NORC-SSP would then implement the actions, where appropriate, or facilitate referrals. The goal was to shift communication between the NORC-SSP and community physicians from reactive and crisis-driven to proactive, thus expanding options to optimize patient care.

Comprehensive presentations were made to community-based physicians to educate them about the NORC-SSP, the Falls Risk Reduction initiative and falls among the elderly in general. Resident-centered falls training and education programs—group and one-on-one—for all seniors at the Queens NORC-SSP were implemented. These programs were aimed at increasing knowledge of risk factors for falls, improving self care and patient confidence, and reducing risk factors for falls.

Brooklyn site

The Brooklyn site theorized that depression among the elderly goes untreated because elderly residents rarely speak to their primary care physicians about their emotional concerns, and because primary care physicians are not well connected to specialty geropsychiatric services, nor sufficiently aware of community-based mental health services.

Therefore, this site sought to establish a proactive, shared care planning approach where mental health assessment data was collected by the NORC-SSP nurse and shared with community physicians for use in identification of problems, diagnosis and treatment. Mental health assessment data was gathered using a standardized depression assessment tool, the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale [22, 23], and a resident passport—a paper record carried to all visits by the resident—was established as the vehicle to share information among providers.

To ensure the community physicians had the resources they needed to use the assessment data comprehensively, the NORC-SSP offered information on community-based mental health services and created opportunities (i.e. professional programs) to bring geropsychiatrists from the local hospital and community physicians together for consultative purposes. The Brooklyn site already partnered with the local hospital for the on-site nurse and this enabled them to facilitate the linkage with the geropsychiatric unit.

It was expected that providing mental health assessment data would assist physicians in both diagnosis and treatment, and involving the NORC-SSP nurse would improve the facilitation of referrals to outpatient mental health providers (where possible and when necessary). The NORC nurse would also serve as the liaison between the specialist and primary care provider, further expanding the linkage between social services and health care.

Education programs for providers and residents were designed to increase knowledge of depression signs, symptoms and treatment strategies, as well as increase awareness of treatment options, services and strategies for improving communication. Although initially designed as formal educational programs, the NORC-SSP modified its approach once it was clear that lectures and group sessions would not work for providers nor residents. Information and training was thus provided in more informal, face-to-face meetings.

Common interventions

The primary intervention across all sites was the systematic sharing of specific information among partners that had in the past only shared such information on an as-needed, ad hoc basis, or crisis-driven basis. In most cases this sharing of information was electronic, which had the added benefits of speed, accuracy and documentation. Table 2 reviews how each site formulated their primary interventions.

Table 2.

Primary linkage interventions: systematic sharing of information

| NORC-SSP site | Target condition | Description of systematic sharing of information |

|---|---|---|

| Mid-Manhattan | Transition from ED to community | • Daily email list of ED discharges within the NORC-SSP catchment area • Electronic medication record housed by and updates by local pharmacies |

| Lower Manhattan | Diabetes | • Shared Electronic Patient Database with diagnostic, treatment and appointment information |

| Queens | Falls | • Consultation letter from NORC-SSP to PCPs with results from the Hartford Falls Risk Assessment Protocol and recommendations for treatment and/or referral |

| Brooklyn | Depression | • Shared Client Passport with results from the Hamilton Depression Screening Protocol and notes on all medical and social work visits |

Secondary interventions at all sites included professional education and training on the linkage intervention for professional staff at partnering organizations, and education and outreach associated with the target conditions for participating NORC residents. The following section reports on the evidence gathered that demonstrates the impact of these interventions.

Findings

Evidence of immediate, intermediate and distal outcomes

Evidence collected suggests that immediate outcomes were widely achieved across sites: knowledge of other sector providers’ capabilities and services increased; communication across providers increased; and identification of target population increased. Intermediate outcomes were also widely achieved: shared care planning increased and continuity of care was enhanced. Furthermore, preliminary evidence suggests that even the more distal outcomes of improvements in disease outcomes were selectively achieved as well.

Each site decided upon a recruitment and enrollment strategy that worked best for them. Each aimed to enroll between 50 and 100 at-risk residents using a convenience sampling strategy. The definition and determination of risk differed by site and program focus. At the Mid-Manhattan site, residents recruited upon discharge from the ED, were enrolled (n=100). At the Lower Manhattan site, Hispanic residents who were also patients of the partnering primary care center were identified, recruited and enrolled (n=39). At the Queens site, a risk screen conducted by NORC-SSP staff during routine home visits identified residents at high-risk for falls (n=100). In Brooklyn, residents known to the NORC-SSP staff to have emotional problems were screened for depression risk, and those found to be at risk were enrolled (n=45).

All NORC-SSPs provided some sort of professional education to increase awareness of their services and capabilities among their new Linkage health care partners. Surveys and interviews with staff—and in some cases residents—assessed whether these educational initiatives were effective (Table 3). The two sites where the NORC-SSP was collaborating with a health care organization were able to demonstrate increased awareness. Indeed, at Lower Manhattan, 100% of resident enrollees queried at the conclusion of the implementation year reported that the primary care center already knew they were NORC program clients at the time of their last visit and/or asked them if they were a client of the Lower-Manhattan NORC-SSP (data not shown).

Table 3.

Increased awareness of partner services

| Site | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Mid-Manhattan | • Seventy-one percent of ED staff correctly identified the NORC program, its services and client eligibility • One hundred percent of ED staff correctly reported the MyMeds program purpose • Eighty-six percent of ED staff correctly identified MyMeds partners • Ninety-three percent ED docs were able to correctly report how to identify a MyMeds member |

| Lower Manhattan | Seventy-four percent of primary care physicians working in diabetes at the primary care center were aware of the Lower Manhattan NORC, and 63% of the joint diabetes Linkage project |

| Queens | • Twelve formal presentations were made by the NORC-SSP for community physicians (3–4 per quarter) • On average, 24 community physicians attended each presentation |

| Brooklyn | Anecdotal evidence (i.e. increases in documented communication between NORC-SSP and physicians during the Linkage project) suggests increased awareness |

The two sites where the NORC-SSP partnered with community-based physicians did not conduct surveys to determine whether there was increased awareness (there was a concern that such surveys would be too burdensome and the NORC-SSPs did not want to risk losing the community physicians’ interest in participating in the Linkage initiative). However, anecdotal evidence suggests that despite the challenge of engaging community physicians, awareness of NORC-SSP activities increased. Both sites used multiple strategies (i.e. formal presentations, office visits, newsletters, direct mailings) to inform community physicians about the NORC-SSP in general, its client population, progress on the Linkage, and the health condition of interest. The Queens site was more successful than the Brooklyn site in getting community physicians to attend formal presentations. This is likely due to the fact that all community physicians targeted by the Queens NORC-SSP were affiliated with the hospital where the presentations were held (this hospital also had an established relationship with the Queens NORC-SSP). The Brooklyn NORC-SSP also had an established relationship with the partnering hospital; however most community physicians targeted for the Linkage project were not affiliated with that hospital. Nonetheless, more informal contact between the NORC-SSP and the physicians—in the form of office visits by the NORC-nurse—led to increased awareness of partner capabilities and services, as per NORC-SSP staff reports as well as the evaluator’s interviews with physicians.

NORC-SSP staff, across all sites, periodically shared information with their Linkage health partners via telephone, fax, mail and in-person visits. Over time, communication became a two-way street (see Table 4), providing evidence that communication was taken to a new level. All sites reported that communication that transpired across settings became more proactive in nature over time. Health providers began reaching out for assistance or information as opposed to only responding to NORC-SSP-initiated requests.

Table 4.

Increased communication among partners

| Site | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Mid-Manhattan | • On average 117 contacts per quarter, 28% related to medications • On average 8% of all contacts with the NORC program were initiated by a pharmacy per quarter |

| Lower Manhattan | • Eighty-four patient-related contacts documented for the 39 test patients; of those, 15 were referrals from the primary care center to the NORC program, 12 were new referrals for home care services, and 15 involved self-management plan interventions |

| Queens | • Approximately 30 contacts (telephone, fax, in person) between the NORC-SSP and community physicians per quarter; increasing percentage initiated by the community physicians (20% on average, per quarter), • NORC-SSP communicated with 39 different community physicians during the project |

| Brooklyn | • Over 50 patient-related contacts per quarter (over 200 by the end of the implementation year for 45 enrolled patients) with 34 participating community physicians • Increasing number initiated by community physicians (11% by the end of the implementation year) |

One goal of increasing awareness and communication was to increase identification of residents in need. Theoretically, increased identification of need would lead to improvements in continuity of care. Table 5 presents evidence demonstrating how the Linkages resulted in greater attention to residents’ needs in the form of enhanced tracking across settings, improved recruitment, and increased service provision.

Table 5.

Increased identification of residents in need

| Site | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Mid-Manhattan | • One hundred percent of ED visits by participating residents enrolled in the MyMeds program were reported to the NORC-SSP • Approximately 30% of the (100) enrollees were new to the NORC-SSP |

| Lower Manhattan | • All enrollees received at least one intervention (e.g. home care referrals, NORC nurse visit, phone reminders, etc.) through the integrated diabetes assessment program, with many receiving multiple interventions |

| Queens | • Approximately 100 client assessments or reassessments were conducted by NORC-SSP staff (approx. 25 per quarter) using the Hartford Falls Risk Assessment protocol • Approximately 70% of those clients assessed for falls risk were determined to be at risk and in need of intervention |

| Brooklyn | • Approximately one-quarter of all participating residents reported that their physician or physician office staff asked if they were a client of the Brooklyn-based NORC at the time of an office visit |

Across the sites, preliminary evidence of increased shared planning was found (Table 6). At some sites this translated into increased referrals among providers. At other sites, this translated into use of shared information for diagnosis or treatment planning. For example, at the Lower Manhattan site, staff reported that prior to the Linkage project there was little interaction between the NORC-SSP and the primary care center. Indeed, the NORC-SSP was unsuccessful at getting the primary care center to respond to inquiries or referrals. However, once the NORC-SSP focused its efforts on diabetes disease management approach, the primary care center took notice, recognizing that this kind of cross-sector collaboration would enable them to extend their effort into the community, a key component of chronic disease management. Soon, the primary care clinic began recruiting NORC-SSP residents to become a part of its ongoing Diabetes Collaborative which included group visits, treatment plans, shared care planning and information exchange.

Table 6.

Increased shared care planning

| Site | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Mid-Manhattan | • Providers reached out to the NORC-SSP to get information on shared patients or to find out how to enroll other patients into the Linkage project |

| Lower Manhattan | • Fifty-two collaborative assessments of diabetes status conducted for the target patients over the course of the year • Quarterly group visits at the primary care center drew approximately 5 NORC program clients each time • Fifty-six percent of residents report seeing the NORC-SSP and the primary care center staff work together to assist them in their diabetes treatment |

| Queens | • Providers responded to assessment findings and care plan recommendations that were sent by the NORC-SSP nurse or presented by the resident • Residents reported that physicians began asking them about mobility issues and falls |

| Brooklyn | • Twenty-four percent residents reported that their physicians either looked or wrote in the client passport |

At the Queens site, residents reported that their doctors were not routinely asking them about falls, nor were clients themselves sharing such information. Once assessment findings and care plan recommendations for residents found to be at-risk were sent to the residents’ physicians, an increasing percentage of residents reported having more discussion with their physicians about mobility issues. Participating residents also began to present their physicians with a chart sticker indicating their participation in the collaborative falls program which helped to initiate a conversation about falls or falls concerns.

Interestingly, although the MyMeds profile was reported to add value to the care planning process for residents, pharmacies and the Mid-Manhattan NORC-SSP—indeed community physicians who learned about it through their patients began requesting information for their other patients—it went unutilized at the ED. Further investigation of why the ED providers did not utilize the profile should be conducted, especially since they were quite enthusiastic about the profile during the planning phase.

Additional anecdotal evidence gathered at all sites suggests increased continuity of care (Table 7). At the Mid-Manhattan site, NORC-SSP staff reported that the sharing of admission and discharge information resulted in greater attention to medication and other health-related issues by program staff and residents. Towards the end of the implementation year the Mid-Manhattan site expanded their MyMeds intervention to include medication education and adherence monitoring for those determined to be at risk. Approximately 60% of new enrollees in the last two quarters of the implementation year received some sort of medication education, including: dosage clarifications, education about what the medications were for, medication reminders, monitoring; and, attention to changes in medications and health status.

Table 7.

Increased continuity of care

| Site | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Mid-Manhattan | • Shared medication information led to sharing of other health information across providers • By the end of the implementation year, 14 pharmacies had joined the MyMeds network |

| Lower Manhattan | • All diabetes linkage program enrollees visited a doctor during the implementation year • Forty-eight percent missed appointments in 2005, only 27% missed appointments in 2006, a 45% reduction |

| Queens | • By the end of the implementation year, the majority of residents surveyed were able to identify falls risks • Increased number of residents report telling their physician about a fall (38% in the 1st quarter, 50% in the 4th) • Increased number of residents made a change to prevent a fall (53% in the 1st quarter; 67% in the 4th) • Fewer participants reported a fear of falling (35% in 1st quarter, 20% in 4th) • Fewer participants reported discomfort speaking with providers about falls |

| Brooklyn | • Increased comfort talking to physicians about emotional health issues (from 12% in 1st quarter to 43% in 4th) • Increased comfort talking to NORC-SSP staff about emotional health issues (from 27% in 1st quarter; 47% in 4th) • Increased numbers of clients reported showing their passports or NORC-SSP chart stickers to physicians over time (10% in 1st quarter; 30% in 4th) |

The MyMeds resident bracelets that were created to better identify Linkage participants turned out to be extremely popular among residents and providers. Residents began requesting additional information (e.g. diabetes status, allergies) for the bracelets. Staff report that having such information on hand made residents feel more confident that there would be ready access to current information if they should need it. Furthermore, residents reported that the bracelet helped them better communicate with physicians. Providers viewed the bracelet as a way to minimize errors and increase continuity of care. Furthermore, the bracelets helped the NORC-SSP communicate with providers, recruit new participants (other residents began inquiring about the MyMeds bracelets) and health partners (14 new pharmacies joined the network by the end of the implementation year), and identify enrollees at the point of hospital admission, pharmacy contact or community-based physician office visit.

At Lower Manhattan, the Linkage led to improved primary and preventive care as well as visit adherence—both indicators of improvements in continuity of care. Furthermore, evidence suggests that clients were taking a more proactive role in their care, which is a precursor to improved care continuity. By the end of the implementation year, 100% of enrollees reported awareness of risk factors for diabetes, 77% reported awareness of proper foot and eye care; 100% reported enhanced confidence in managing their diabetes (up from 65% in quarter 1); and, 100% enrollees had a primary care center-developed Self Management Plan (data not shown). Access to health information enabled the NORC-SSP to track health trends within its target population for the purposes of health promotion planning. Indeed the diabetes linkage initiative has led to additional joint programming focusing on other health conditions at this site.

At the Queens site, improvements in resident knowledge of falls risk and self care provides preliminary evidence of improved care continuity. Approximately 20 lectures or health promotion activities were provided to participating residents over the course of the Linkage implementation year with an average attendance of 20 residents at each. Falls-related information was included in the quarterly newsletters; over 1400 newsletters were distributed each quarter. Furthermore, staff report that the adoption of care plan recommendations made by the Queens NORC-SSP to community physicians about residents’ falls risk provides evidence of shared care planning as well as increased continuity of care. Indeed, the Queens site witnessed physician follow-up on NORC-SSP suggested recommendations and subsequent physician-driven referrals to implement recommendations (e.g. home care, physical therapy, and counseling, ordering of durable medical equipment). At the Brooklyn site, evidence of increased resident self-advocacy represents a critical step towards improving continuity of care.

Despite the short time period, evidence of the more distal care outcome was found across sites (Table 8). At the Mid-Manhattan site, preliminary evidence suggests that enrollees experienced a decrease in inappropriate hospital readmissions over the course of the implementation year. At the Lower Manhattan site, evidence that the immediate and intermediate outcomes of increased knowledge, awareness and shared care planning were beginning to make a difference in disease outcomes can be found in the clinical assessments. Of particular interest is the finding that Linkage enrollees were improving at a greater rate across clinical parameters than the primary care center’s diabetes patients who were not clients of the NORC-SSP. At the Queens site, it is important to note that the evidence of decreased falls risk enabled the NORC-SSP to successfully negotiate for environmental improvements. As a direct result of this initiative, the housing company installed hand rails on all outside steps leading into the garden apartment buildings. Finally, the Brooklyn site was able to document improvements in emotional health status among enrollees. Further investigation of the Linkage components that may be responsible for having a positive impact on care outcomes across sites is warranted.

Table 8.

Improved care outcomes

| Site | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Mid-Manhattan | • Number of ED revisits at 30 days decreased from the beginning of the implementation year to the end, from 21% of all ED visits to 5% |

| Lower Manhattan | • By the end of the implementation year, enrollees were showing improved levels of A1c (14% increase in number of enrollees with A1c <7), blood pressure (19% increase in number of enrollees with blood pressure <130/80) and LDL (12% increase in enrollees with an LDL <100), and were getting a greater number of annual eye (10% increase) and foot exams (38% increase)8 |

| Queens | • Hartford assessment scores improved over the four quarters (approx. 60% decreased risk; approx. 30% stabilized risk; approx. 10% increased risk) |

| Brooklyn | • Improved emotional health status doubled (from 41% in 1st quarter to 88% in 4th) |

Looking across all fours sites

Evidence gathered suggests that the established linkages facilitated considerable progress towards achieving the overarching goals of the Linkage Initiative: increasing access to care, improving continuity of care, and improving care quality and outcomes. Yet, the value of the Linkage project extends beyond the outcomes of the specific linkages. Indeed, the most profound finding of the Linkage evaluation is not a particular disease management improvement—however critical and important those are—but rather the evidence that suggests that relatively simple linkages can indeed be forged between health care providers and NORC-SSPs to promote population-based health. Organizations were asked to work in ways they never had before and by doing so were able to maximize their own potential to provide comprehensive care to their clients/patients. Indeed, by the end of the implementation year, each of the four sites had plans for either sustaining and/or expanding some aspects of the established linkage to additional populations, health problems and/or service providers.

Strength of the established linkages

All four Linkage sites were successful in establishing new linkages—defined as specific collaborative service mechanisms that did not exist prior to the Linkage Initiative—between the NORC-SSP and at least one health care provider, although the strength and viability of the linkages varied across sites. One of the four sites established a new protocol with its existing NORC-SSP health care partner in addition to establishing linkages with new, local health providers. The other programs worked exclusively with providers who were not formal partners in the NORC program.

Strength and viability of the successful linkages were determined based on the level of shared responsibility for linkage activities across organizations and the extent to which the expected linkages occurred. The Lower Manhattan site was determined to have created the strongest and most viable linkage, with equal distribution of responsibility and initiative (50:50 both Lower Manhattan NORC and primary care center). Both the Mid-Manhattan and the Queens site linkages were determined to be of moderateߝstrong intensity, with a greater level of shared responsibility and ownership among the NORC-SSP partners but a significant contribution by the health care partners (60:30:10 Mid-Manhattan NORC 60% initiative: hospital 30% initiative: pharmacies 10% initiative; 75:25 Queens NORC 75% initiative: community physicians 25% initiative). The Brooklyn linkage was determined to be of moderateߝlow intensity; as it was primarily NORC-driven with limited physician initiative (90:10; Brooklyn NORC 90% initiative: community physicians 10% initiative).

Discussion and critical success factors

Discussion

Using simple, familiar and relatively low-tech approaches to sharing critical patient information among collaborating organizations, inter-sector linkages were successfully established at all four Linkage sites. The real innovation across all four Linkage sites was the systematization of communication and sharing of information. Rather than remaining in the traditional, individual-focused and reactive mode, all four NORC-SSPs took on a population-based health and social care approach that included outreach, assessment, service coordination and provision, and ongoing follow-up. Specific problems with biopsychosocial components were selected and agreed upon by both collaborating organizations. Strategies for sharing streamlined, essential care management-related information were carefully crafted and implemented with the providers’ information needs in mind. Interventions were designed using comprehensive and sound program and evaluation planning models and methods. Linkages between SSPs and large health care organizations were able to utilize more sophisticated computer technology and patient databases. Linkages between SSPs and community-based physicians were able to use existing system fragmentation as the rationale for coming together and for finding new, more effective ways to package critical information.

Interestingly, the finding that these micro-level collaborations, using simple, cross-sector linkages are effective strategies for integrating health and social services may represent an additional level on Leutz’s integration continuum [1]. According to Leutz there are three levels of integration: Linkage, Coordination and Full Integration. Each level is characterized according to client need. Patients with significant (i.e. moderate/severe), broad, long-term and frequent needs, and who are unstable and unable to engage in self-care are best served by the fully-integrated model, operating at one end of the continuum. Patients with mild/moderate, non-urgent, mostly short-term and readily defined needs, and who are stable and able to engage in self-care are best served at the other end of the continuum, by linkage models. Patients with needs that fall in-between those described above are best served by the level of Coordination.

Whereas the Linkage approach, according to Leutz, is one where ‘special relationships’ between organizations is not required, the Coordination approach requires explicit structures and individual managers to coordinate benefits and care across settings. Indeed, the Coordination approach is a more structured form of integration that focuses on coordinating services, the sharing of clinical information, and managing transitions between settings. Coordination is described as ‘identifying points of friction, confusion or discontinuity between systems and established structures and processes to address problems’ [1]. While the linkages established through micro-collaborations in this study certainly do not meet the criteria of Leutz’s full integration (i.e. pooled resources), they don’t fit well in either the Linkage or Coordination categories either (according to Leutz, a short hand measure to compare levels of integration is case management: none in linkage, varied in coordination and team in full integration). Instead, these micro-collaborations fit better across the first and second level, representing both the Linkage and Coordination model of integrating care. Sites shared findings from selected assessments and shared access to charts and care plans. Indeed, for select sites in this study, a single coordinating care manager—typically employed by the NORC-SSP ߝ worked with existing providers across all services and settings.

Upon reflection, Leutz [3] recognized that it was rather common for organizations to integrate different aspects of their programs to different degrees, depending in part on existing opportunities. In reality, the relatively pure examples of full integration, coordination and linkage are relatively uncommon and in the case of full integration and coordination, prohibitively complex for most to attempt. Leutz noted that even the explicitly coordinated PRISMA model9 mixed elements (i.e. no financial or team integration, but a common electronic clinical record). Another example of the mixed model is the Social HMO, which fully integrated acute care and private financing to create and pay for new benefits, but which used case managers to coordinate social and medical care.

Changes in health outcomes for seniors take a long time and require tremendous resource and time commitments on the part of the partners, even in the absence of full integration. However, findings from this study suggest that less intensive, micro-level collaborations across sectors and settings have the potential to achieve real benefits for patients and providers. All four Linkage site demonstrations produced evidence demonstrating that increased knowledge and awareness was achieved; critical changes in provider and client behavior was observed; and despite the relative simplicity of the interventions and the short timeline, distal outcomes showing improvements in health status was documented.

Critical success factors

Seven critical success factors emerged from this evaluation that increase the likelihood that linkages will be implemented, effective and sustained: 1) careful goal selection; 2) realistic expectations for implementation environment; 3) appropriate role for clients; 4) realistic interventions; 5) speaking the same language; 6) continuous focus on outcomes; and, 7) stable leadership.

Careful goal selection

Linkage collaborations must focus on goals that speak to the missions of all participating organizations. Mission-driven goals are more likely to generate interest and buy-in among organizations. Furthermore, linkage goals need to be manageable, mutually beneficial and commonly defined. Open and regular communication among linkage providers is essential to ensure that goals are being defined similarly. If goals are not aligned there will be negative repercussions for implementation, outcomes, sustainability and future interaction among organizations. It is critical that the primary goal of the linkage collaboration be improving community health not increasing referrals, as the latter will not always meet expectations and should not jeopardize participation. All organizations participating in a linkage need to be in it for change.

The Brooklyn case offers an example of the importance of carefully aligning goals: both the NORC-SSP and the hospital partner believed—and these beliefs are validated in the literature—that it was within their mission, and good heath policy, to help community physicians better manage mental health conditions among elderly patients. Indeed they set physician education and geropsychiatric consults as project goals. However, it is unclear whether the physicians themselves saw better management of mental health conditions as one of their practice goals. Certainly several physicians did value the education and outreach conducted by the NORC-SSP; however, none showed up for the educational sessions and none took advantage of the geropsychiatric consults.

The experience at the other three sites was quite different. Collaborative planning by the other participating organizations ensured that goals were aligned. In Mid-Manhattan, improved medication management was seen as critical by the NORC-SSP, the pharmacies and the hospital ED. In Lower Manhattan, improved diabetes management was a pre-existing goal at both the NORC-SSP and the primary care center. In Queens, fall reduction was a common goal of the NORC-SSP and CPs.

Realistic expectations for implementation environment

Sites that carefully thought out the flow of the intervention were able to bring the right providers around the table and were realistic in their expectations for what each provider could or would contribute. The collaborating organizations must represent the ‘right’ mix for the intervention to be effectively implemented. The intervention theory may be sound but still apt to fail if the implementation environment is faulty.

One example of the importance of this critical factor has to do with the position of the hospital partner. The Queens site experienced a high turnout of community physicians at the educational sessions, and active participation of the community physicians in the linkage intervention. This outcome speaks to the position of the hospital partner with whom both the community physicians and the NORC-SSP were affiliated. In fact, at the three most successful sites (i.e. Queens, Mid-Manhattan and Lower Manhattan) there was a dominant health care provider that was able to use its institutional interests to advance the goals of the linkage. The site that struggled the most—the Brooklyn site—tried to link physicians and clients to a hospital that was not centrally located and where many physicians were not formally affiliated, resulting in a weaker outcome than expected. Furthermore, the Brooklyn site’s efforts to link with community-based mental health providers were limited because of regulations regarding visits and reimbursement, and because these providers were not included around the table from the outset.

Appropriate role for clients

All sites started with high expectations of clients in terms of how they could help to link various providers through increased advocacy. Ultimately it was realized that the providers need to drive the communication and information sharing and that any attempt by the client was in addition to the existing mechanism. There is a delicate balance between increasing patient autonomy and abdicating professional responsibility. Health and social service organizations must be ever vigilant in carefully balancing the risks and benefits of promoting patient self-advocacy.

The experience of the MyMeds program at the Mid-Manhattan site offers a case in point. Initially, it was unclear what role clients could play in managing their medications. It quickly became obvious that clients had significant deficits in medication dosing and administration knowledge. The NORC-SSP began a more intensive medication education and adherence program in response. It also began using personalized bracelets to ensure accuracy of information transfer.

Another example of the importance of thinking carefully about the appropriate role for clients can be seen at the Brooklyn site. This site created passports for clients to carry back and forth from medical appointments and social service visits. The expectation was that clients would show the passport to the doctor, or social service provider, and each provider would use their counterpart’s clinical notes to provide more tailored care. It quickly became obvious that an additional intervention was needed to realize the shared care planning expectation. The NORC-SSP nurse began making office visits to physician offices to share patient information and request feedback. This approach, together with the client role, resulted in a number of very interesting cross-provider collaborations.

Realistic intervention design

Sites that developed interventions that fit within the existing organizational structures—as opposed to those that attempted to change the existing structure with their intervention—were more successful. Attempting to make radical changes in existing service models is unrealistic; incremental changes can result in real improvements in care.

One example of the importance of this critical factor has to do with reliance on technology. While it is enticing to aim for the development of shared electronic databases, there are a number of practical barriers that must be overcome, including disparities in levels of preparedness for electronic communication across settings and sectors and HIPAA rules regarding sharing of patient information. The two sites that were successful in establishing a shared electronic database—the Mid-Manhattan and Lower Manhattan sites—did not wait for the technology. They had alternative, lower-tech mechanisms in place which enabled the interventions to be implemented despite delays in the environment (i.e. the development of shared databases).

Speaking the same language

It is essential that NORC-SSPs learn the ‘language’ of health care. They need to carefully select content and format of information to share across sectors so that they are not tuned out. The sites that developed communication systems familiar to the collaborating health care provider found greater response.

One example of this critical factor can be found at the Queens site. The letter that was used to communicate with physicians about a patient’s falls history, current falls risks and treatment concerns was formatted based on a typical medical consultation letter. This was done intentionally so physicians would find the correspondence familiar and easy to respond to. Indeed the NORC-SSP nurse included a series of possible next steps that could be checked off and signed by the physician to have implemented (e.g. referrals for physical therapy).

This realization that health and social service providers were essentially speaking ‘at’ each other rather than ‘with’ each other about managing chronic illnesses led the United Hospital Fund to develop the follow-up Health Indicators Project. The Health Indicators project uses data to help NORC-SSPs take a population-based approach to care management rather than responding to health and social issues one client at a time.10 Designing care approaches using evidence-based strategies has further enabled NORC-SSPs to speak ‘with’ health care organizations about community health and risks and collaborative, integrated approaches to minimizing risks and improving health outcomes. Learning the language of ‘data’ has resulted in a different level of buy-in from health care organizations, and a different level of ownership to shared care planning projects for all providers.

Continual focus on outcomes

The surest way to get buy-in for a linkage program by executive leadership is through the demonstration of good outcomes. Sites should not wait until the implementation phase is complete to review and present their findings. Ongoing tracking allows for the demonstration of small improvements, which are essential to make the case for sustainability. There are additional benefits to the continual focus on outcomes. For example, staff at participating organizations get to see the fruits of their labor sooner than if assessment of outcomes is left until the end. This not only creates goodwill and trust, but also enables sites to become aware of problems that need modification (which saves considerable time if found early) or new, unexpected linkages that deserve attention (and would be missed without continuous quality improvement).

The three most successful Linkage sites—Mid-Manhattan, Lower Manhattan and Queens—all presented mid-year findings at meetings where the NORC-SSP, the existing NORC health care partner, the health collaborators, and the funders were present. It was clear that having the evidence—albeit suggestive at best at the mid-point—was empowering and motivating for the sites. Indeed, this phenomenon has been seen in the Health Indicators project as well.

Stable leadership

When asked to describe the source of leadership in the partnership, the overwhelming majority (79%) of linkage respondents described leadership in their collaborative as “provided consistently by multiple individuals acting as a coalition.” This seems to be the ideal set-up for linkages, assuming all organizational providers are represented. Interestingly, respondents from the Mid-Manhattan site, one of the most successful Linkage sites, were in complete agreement on this description. On the other hand, the Brooklyn site, perhaps the least successful site, overwhelming reported that there was no discernable or consistent source of leadership at all. The other two sites fell somewhere in the middle on this question. Also interesting is the fact that the Brooklyn site was the only site where respondents were split on whether the linkage program had a clear vision and strategy. The fact that both these findings were consistent on the six months and 12 months stakeholder survey suggests that an analysis conducted early on can be predictive of later success. It may also provide an opportunity for adjustment and improvement in collaboration before it’ too late.

Finally, while the age-old caution of resisting a champion-led program applies here as well, it should also be noted that program champions are critical in the planning and early implementation phase. During the critical formative period, before there is considerable buy-in, someone must take on the task of defending and promoting the program. However, once commitment to the program is more consistent and diverse, the champion models become risky and leadership must become less centralized for the linkage to be sustainable. Having more than one point person spearheading the linkage can help to ensure that even during periods of flux at one partner organization, partnership activities are not significantly affected. Much has been written on the importance of recognizing such challenges and building flexibility into a collaborative effort to accommodate periods of disruption at individual organizations.

Lessons for the future

It is extremely challenging for organizations to think about doing things differently, both health care organizations and NORC-SSPs are quite entrenched in existing thinking, both working in vacuums limiting their ability to help clients/patients. However, given the opportunity, organizations will rally to the cause. Health providers have long struggled with ways to extend their reach beyond the hospital or office. They have long known that they are only offering the patient one piece of the puzzle, but they are typically large, fast-paced environments and cannot easily stop to think through the how and where and who of reaching out beyond their traditional confines. Even a powerful body, such as the Joint Commission11 has struggled with effectively enforcing continuity of care. NORC-SSPs, on the other hand, are designed to be ‘responsive’ to their communities and therefore may have a greater ability to stop and think about process and make changes; however, their standard approach to practice (i.e. tracking number of services provided) and traditional understanding of partnering, coupled with a lack of technological sophistication, has made them invisible, misunderstood and/or unreachable by health providers. It has also limited their reach.

The Linkage project supported NORC-SSPs efforts to reach out to health providers by helping them ‘build capacity’—that is, teaching them how to design measurable interventions, how to think about data, how to track outcomes, how to share information and what information to share. NORC-SSPs learned how to have conversations with health care providers about advancing shared organizational goals, conversations that made health care providers more aware of how NORC-SSPs could offer up the other piece of the puzzle. As stated previously, the Linkage project informed the Health Indicators project which continues today helping NORC-SSPs become more proactive by teaching them how to identify the most pressing health needs of their communities, how to use the information to tailor program planning, quality improvement efforts and resources, and how to track changes resulting from targeted biopsychosocial interventions.