Abstract

The GLC1A gene (which encodes the protein myocilin) has been associated with the development of primary open angle glaucoma. Bacterial artificial chromosomes containing the human GLC1A gene and its mouse ortholog were subcloned and sequenced to reveal the genomic structure of the genes. Comparison of the coding sequences of the human and mouse GLC1A genes revealed a high degree of amino acid homology (82%) and the presence of several conserved motifs in the predicted GLC1A proteins. The expression of GLC1A was examined by Northern blot analysis of RNA from adult human tissues. GLC1A expression was observed in 17 of 23 tissues tested, suggesting a wider range of expression than was recognized previously. The comparison of the human and mouse GLC1A genes suggests that the mouse may be a useful model organism in studying the molecular pathophysiology of glaucoma.

[The sequence data described in this paper have been submitted to the GenBank data library under accession nos. AF049791–AF049796.]

The glaucomas are a heterogeneous group of disorders that are the second leading cause of blindness in developed countries overall and the leading cause of blindness in African American individuals (Leske 1983). Glaucoma affects ∼2.3 million Americans and blinds ∼12,000 of them per year (Tielsch 1993). The most prevalent form of glaucoma is primary open angle glaucoma (POAG), a progressive disease of the optic nerve characterized by degeneration and cupping of the optic nerve, loss of peripheral visual field, and increased intraocular pressure. Evidence indicates that POAG is genetically heterogeneous with a complex mode of inheritance. An early onset form of POAG known as juvenile open angle glaucoma (JOAG) is an autosomal dominant disorder with high penetrance.

Sheffield et al. (1993) used genetic linkage analysis to map JOAG to chromosome 1. This GLC1A locus was subsequently refined (Sunden et al. 1996) and the disease-causing gene was identified using a combination of positional cloning and candidate gene studies (Stone et al. 1997). The gene codes for a protein that was initially named trabecular meshwork glucocorticoid response protein (TIGR) (Polansky et al. 1997). Kubota et al. (1997) named the protein myocilin because sequence homology analyses revealed similarities with bullfrog olfactomedin and Dictostelium discoideum myosin. In this report we refer to the gene by the locus designation, GLC1A, to reflect the known disease-causing nature of the gene; we refer to the protein product as myocilin in accordance with the official protein name given by the HUGO Nomenclature Committee.

A variety of glaucoma-causing mutations (both POAG and JOAG) and non-disease-causing polymorphisms have been identified in the GLC1A gene (Stone et al. 1997; Alward et al. 1998). Both the normal function of the GLC1A gene and the mechanism by which mutations in the gene lead to glaucoma are unknown. GLC1A mRNA expression has been demonstrated in retina, ciliary body, iris, heart, and skeletal muscle by Northern blot analysis and the GLC1A protein product has been immunolocalized to the cytoplasm of the retina in a pattern that is consistent with a role in basal body function (Kubota et al. 1997; Ortego et al. 1997). Expression in the trabecular meshwork has also been demonstrated (Polansky et al. 1997).

In this report we present the complete coding sequence and genomic structure for both the human and mouse GLC1A genes. The human and mouse GLC1A genes and their predicted proteins are compared to identify conserved motifs. Finally, we demonstrate via Northern blot analysis that GLC1A is expressed much more widely in adult human tissues than was recognized previously.

RESULTS

Sequence and Genomic Structure

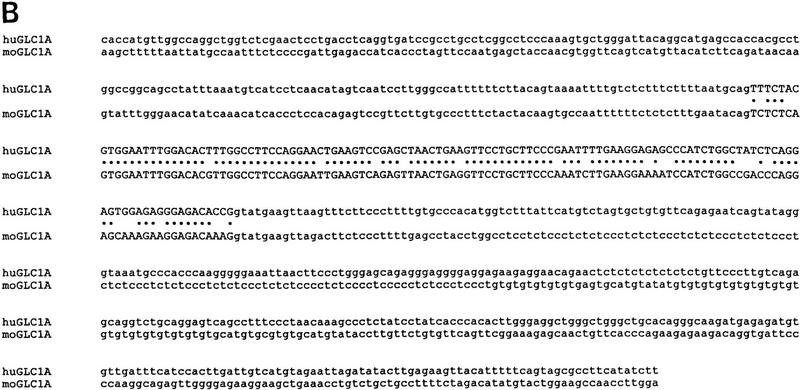

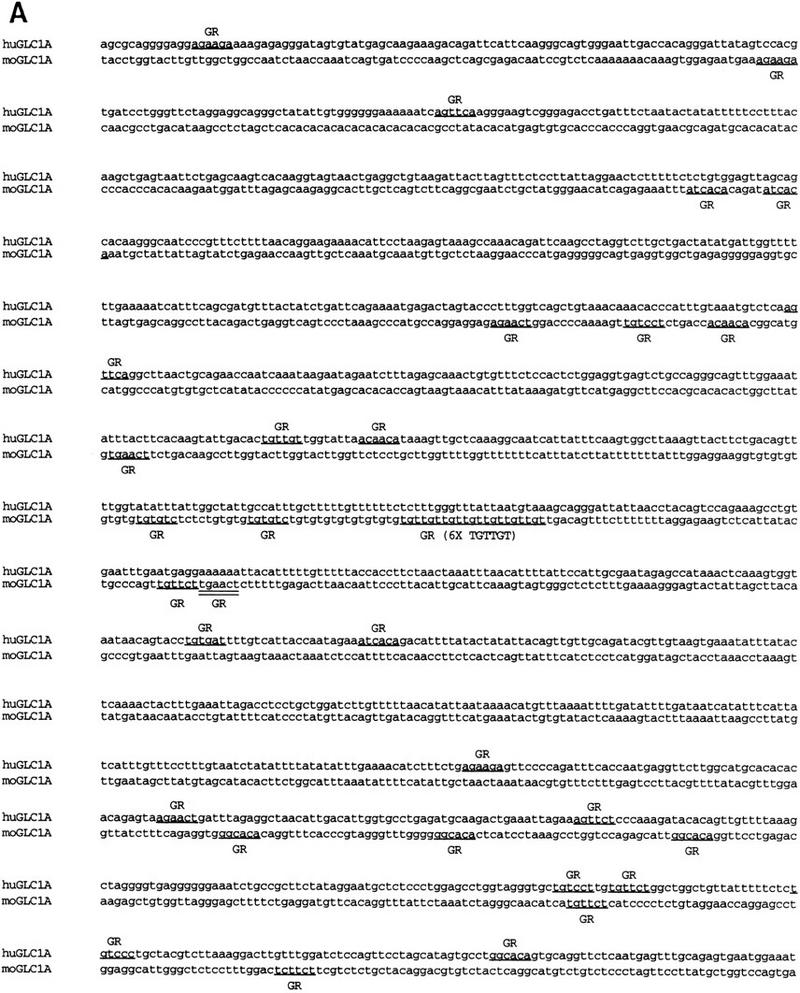

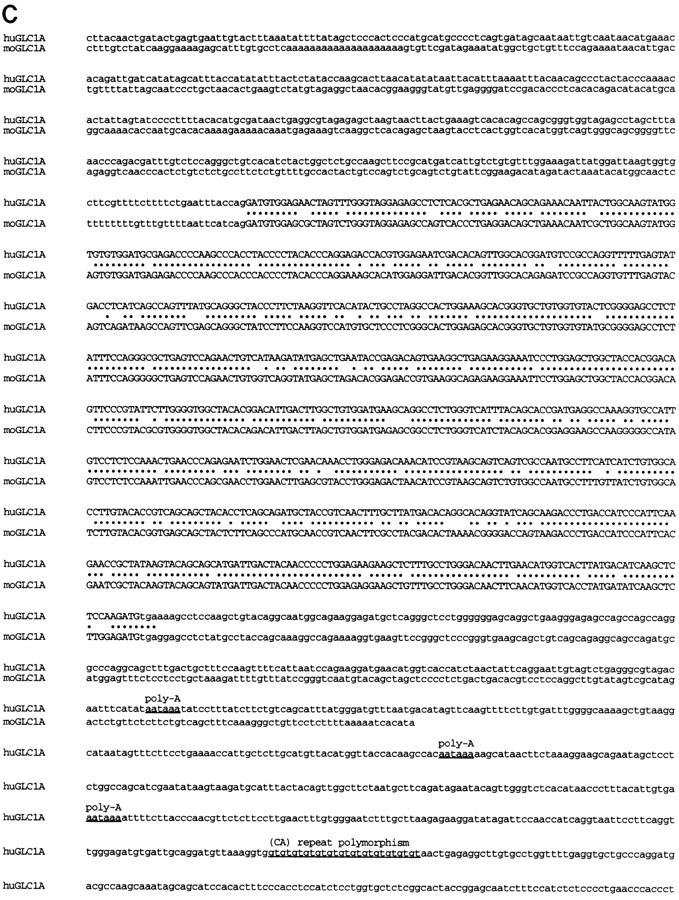

The human and mouse GLC1A gene sequences are shown in Figure 1. Both the human and mouse GLC1A genes are composed of three exons. Exons 2 and 3 are 126 and 782 bp long in both genes, whereas exon 1 is 604 bp in the human gene and 562 bp in the mouse gene. Exon–intron borders are completely conserved between mouse and human. The human- and mouse-coding sequences are 83% identical at the nucleotide level and predict proteins that are 82% identical at the amino acid level.

Figure 1.

The three exons of the human and mouse GLC1A genes and flanking sequences are aligned in A, B, and C and are not continuous. Exon sequences are in uppercase letters; flanking sequences are in lowercase letters. (•) Nucleotides conserved between mouse and human. (A) Exon 1 and flanking promoter and intron 1 sequences. A subset of putative promoter and enhancer elements are underlined and labeled. (GR) GRE half-sites. A CA repeat polymorphism in the 5′ flanking region of the human GLC1A gene is underlined and labeled here and in C (downstream of the human GLC1A gene). (B) Exon 2 and flanking intron 1 and intron 2 sequences. (C) Exon 3 and flanking intron 2 and downstream sequences. Poly(A) signal sequences are underlined and labeled. GenBank accession nos. for these sequences are AF049791–AF049796.

Many putative transcription regulatory sequences were identified in the upstream region of the GLC1A genes (Table 1; Fig. 1A). Three polyadenylation sites were located in the 3′ UTR of the human gene at positions 1714, 1864, and 2006 bp following the putative start codon (Fig. 1C). Additionally, the human GLC1A gene was found to be closely flanked by two CA simple tandem repeat polymorphisms (STRPs) that proved to be useful genetic markers for tracing the segregation of the gene within families (Fig. 1A,C).

Table 1.

Putative GLC1A Promoter and Enhancer Elements

| Human and mouse | Human only | Mouse only |

|---|---|---|

| AP-1 | AFP1 | DTF-1 |

| AP-2 | CF2-II | GATA-2 |

| AP-3 | CP2 | Hb |

| AR | DBP | LVa |

| c-ETS | Elk-1 | LVb-binding factor |

| c-Myc | G6 factor | MAF |

| C/EBP | HNF-1 | MAZ |

| CAC-binding protein | HOX-D8 | muEBP-C2 |

| Dr | HOX-9 | NF-E2 |

| En | HOX-10 | PTF1-β |

| F2F | IRF | TFE3-S |

| GATA-1 | LyF-1 | USF |

| GFII | MBF-1 | |

| GR | MCBF | |

| HiNF-A | myogenin | |

| HNF-3 | NF-InsE | |

| MBF-1 | TCF-2α | |

| MEP-1 | TDEF | |

| NF-1 | TGT3 | |

| NF-GMb | TII | |

| N-Oct-3 | UBP-1 | |

| Oct | WT-1 | |

| PEA3 | ||

| Pit-1a | ||

| PPAR | ||

| PR | ||

| PU.1 | ||

| PuF | ||

| Sp1 | ||

| SRY | ||

| TCF-1A | ||

| TFIIA | ||

| TFIIB | ||

| TFIID | ||

| TFIIE | ||

| TFIIF | ||

| TMF | ||

| YY1 | ||

| Zeste |

The human GLC1A gene has been placed on the chromosome 1 physical map between four flanking genes (SELL, SELE, GLC1A, APT1LG1, AT3) (Stone et al. 1997). The mouse homologs of these flanking genes are present in the same order on mouse chromosome 1, suggesting that the mouse GLC1A gene is located in this syntenic region between the mouse homologs of SELE and APT1LG1.

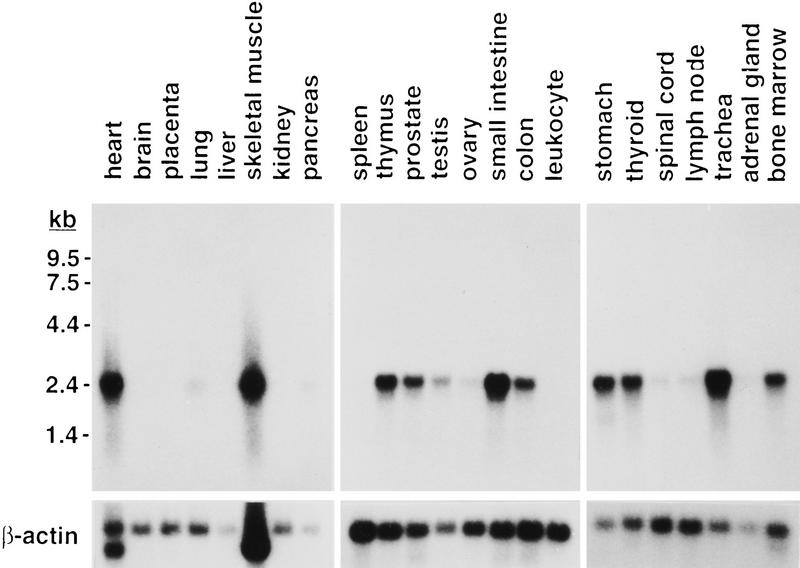

Gene Expression

Database searches suggested that the GLC1A gene is expressed in the ciliary body (GenBank accession nos. R95491, R95443, R95447, and R47209) and in the retina of the human eye (GenBank accession no. D88214), as well as in the trabecular meshwork (GenBank accession no. U85257). Expression in the human retina, ciliary body, iris, heart, and skeletal muscle was also shown previously by Northern blot analysis (Kubota et al. 1997; Ortego et al. 1997). We performed Northern blot analysis of several adult human tissues and observed high levels of expression of the 2.3-kb mRNA in a wide range of tissues including heart, skeletal muscle, stomach, thyroid, trachea, bone marrow, thymus, prostate, small intestine, and colon (Fig. 2). Less abundant GLC1A expression was observed in lung, pancreas, testis, ovary, spinal cord, lymph node, and adrenal gland. GLC1A transcripts were not detectable by Northern blotting in brain, placenta, liver, kidney, spleen, or leukocytes. A similar expression pattern was observed in the mouse (R. Swiderski and V. Sheffield, unpubl.). To test the possibility that certain regions of the brain were under-represented in poly(A)-selected mRNA of total brain tissue, we also hybridized a Northern blot prepared with RNA from several different regions of the brain with the GLC1A probe. Hybridization was observed in the spinal cord, but not in the cerebellum, cerebral cortex, medulla, occipital lobe, frontal lobe, temporal lobe, or putamen (data not shown).

Figure 2.

GLC1A expression in human adult tissues. Northern blot analysis of 2 μg of poly(A) RNA per lane probed with 32P-labeled GLC1A cDNA. The autoradiographic exposure was 21 hr, 6 hr, and 18 hr for left, center, and right filters, respectively. Blots were stripped of radioactivity and rehybridized with a 32P-labeled β-actin cDNA.

Protein Analysis

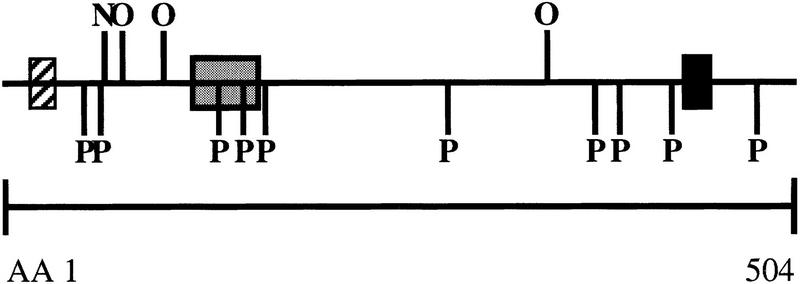

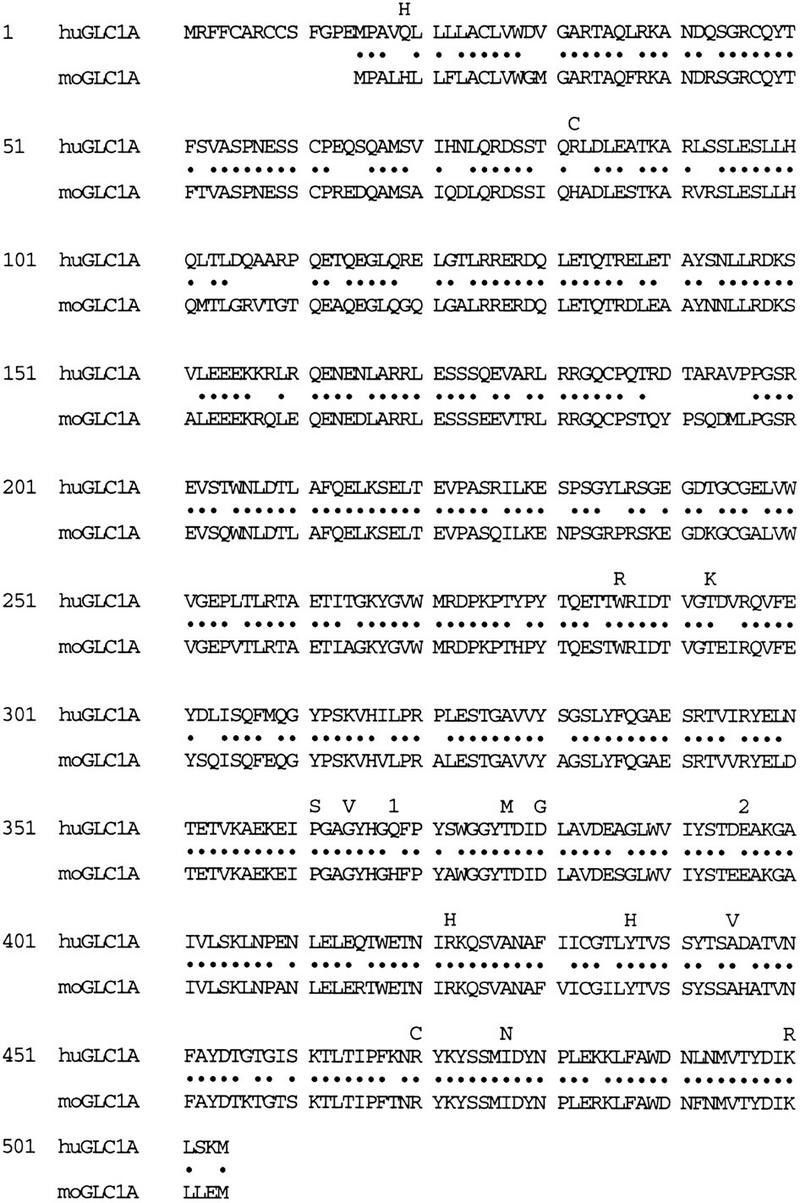

Conceptual translation of the human GLC1A gene predicts a protein that consists of 504 amino acid residues with a molecular mass of ∼57 kD, whereas the predicted mouse GLC1A protein sequence consists of 490 amino acids with a molecular mass of 55 kD. Figure 3 illustrates protein motifs that are present in both human and mouse GLC1A proteins. Both human and mouse GLC1A proteins contain a leucine zipper domain, 10 putative phosphorylation sites, and four putative glycosylation sites. Further analysis of the amino terminus reveals a potential signal sequence. Hydrophobicity analysis reveals a hydrophobic region between amino acids 17 and 37 and 426 and 44. The length and degree of hydrophobicity of these domains, however, suggest that they are not membrane spanning. The carboxy-terminal three amino acids of human GLC1A protein are serine, lysine, and methionine. This sequence has been shown to function as a peroxisome targeting sequence in other proteins (Subramani 1993). No such putative targeting sequence, however, is present in the mouse protein. Western blot analysis of human GLC1A protein reveals bands at 57 and 59 kD (data not shown), confirming the predicted protein size and providing evidence that the protein may be post-translationally modified.

Figure 3.

GLC1A protein motifs. Putative GLC1A protein motifs that are conserved between human and mouse are shown. (Hatched box) Hydrophobic domain/signal peptide; (solid box) hydrophobic domain; (shaded box) leucine zipper domain. (P) Phosphorylation sites; (O) O-linked glycosylation sites; (N) N-linked glycosylation sites.

Conservation of Amino Acid Residues for Which Variants Have Been Identified

Evaluation of patients with adult and juvenile onset POAG has provided strong evidence that mutations in the GLC1A gene cause these disorders (Stone et al. 1997; Alward et al. 1998). Twenty-six amino-acid changing sequence variants have been identified in affected individuals. Sixteen of these variants are likely disease-causing mutations because they meet the following criteria. They are present in glaucoma populations, they are absent from control populations, and they alter the amino acid sequence of the GLC1A protein (Alward et al. 1998). These criteria are not foolproof and any of these variants could still be a non-disease-causing polymorphism. One method of gaining additional insight into which sequence variants are likely disease-causing mutations is to evaluate the conservation of variant residues across species. This type of analysis, however, cannot be made effectively when the degree of conservation is very high. For example, Figure 4 shows the position of the 16 mutations with respect to the mouse and human GLC1A protein sequences. Of these, 14 are missense mutations that result in single amino acid substitutions, 12 occur at amino acids that are conserved between human and mouse, and 2 occur at amino acids that are not conserved. The two remaining mutations include an insertion that disrupts two conserved amino acids and a nonsense mutation that results in the truncation of the terminal 136 amino acids of the GLC1A protein and the loss of 121 conserved residues. Therefore, the percentage of disease-causing mutations found in amino acids conserved between mouse and man (88%) is not significantly different from the overall protein conservation across species (82%).

Figure 4.

Alignment of the proteins predicted by the mouse and human GLC1A genes. (•) Amino acids conserved between mouse and human. The locations of disease-causing mutations identified previously in the human GLC1A gene are indicated (Stone et al. 1997; Alward et al. 1998). For each missense mutation, the mutant residue is shown directly above the wild-type amino acid. (1) The location of a nonsense mutation; (2) the location of an insertion mutation.

Sequence comparison across species, however, can provide evidence that a putative mutation is likely to be a non-disease-causing polymorphism when the putative mutation converts the human residue to that of the corresponding mouse residue. For example, the nineteenth residue in the human myocilin protein is glutamine, whereas the corresponding residue in the mouse protein is histidine (Fig. 4). This suggests that further study of the GLN19HIS sequence variation in human patients may show it to be a non-disease-causing polymorphism.

DISCUSSION

We report the genomic structure of the human GLC1A gene and its mouse ortholog. The genes are composed of three exons that, when translated, encode a 57-kD protein (human) or a 55-kD protein (mouse). The largest open reading frame (ORF) in the GLC1A cDNA sequence begins with the first ATG and is in-frame with a second ATG, 42 bp downstream. Additional studies will be necessary to determine where translation is initiated.

Several putative promoter and enhancer elements have been identified in the upstream region of human and mouse GLC1A genes (Table 1). Previous reports have suggested that GLC1A expression exhibits a delayed induction in response to glucocorticoids (Polansky et al. 1997). This effect may be mediated through glucocorticoid response elements (GREs) in the GLC1A promoter or enhancer regions. No classic GREs (AGAACAnnnTGTTCT) were identified in the 1900 bp upstream of the putative translation start site in the human and mouse GLC1A genes; however, several sequences similar to GRE half-sites were identified (Fig. 1A). Glucocorticoid receptor has been shown to bind to various arrangements of GRE half-sites and cause a delayed induction of gene expression (Chan 1991). Therefore, the glucocorticoid induction of GLC1A expression may be mediated through the GRE half-sites, classic GREs located farther upstream, or a secondary response to glucocorticoids.

Of the 16 known GLC1A mutations that have been associated with POAG, all but 2 alter conserved amino acid sequences (Fig. 4). All but the two mutations in nonconserved amino acids are located in exon 3 of the gene. The 14 mutations in exon 3 are distributed evenly across the exon and as a group do not disrupt any known functional domains. The predominance of mutations in exon 3 suggests that mutations elsewhere in the gene may not cause disease, may cause a phenotype other than glaucoma, or may be lethal. Additional studies are needed to evaluate these possibilities.

The human and mouse GLC1A genes exhibit a high degree of sequence conservation. Comparison of these genes supports the functional significance of conserved domains. Leucine zipper motifs, hydrophobic regions, potential glycosylation, and phosphorylation sites are conserved across species suggesting a conserved functional role of these sequences. Some predicted functional domains, such as a putative peroxisomal targeting sequence and several possible phosphorylation and glycosylation sites in the human GLC1A gene, are not conserved across species, implying that these sequences are not crucial to GLC1A protein function.

Initial studies suggested that expression of the GLC1A gene was limited to the eye, heart, and skeletal muscle (Kubota et al. 1997; Ortego et al. 1997; Polansky et al. 1997). Our results, however, suggest a more extensive expression of the GLC1A gene. Northern blot analysis reveals that GLC1A is expressed in 17 of 23 human tissues tested, including many nonocular and nonmuscular tissues. Although these data do not suggest a particular function, they imply that the GLC1A protein has a general biological role that is not limited to the eye.

Two lines of evidence suggest that the human and mouse GLC1A genes are functionally similar. The DNA and protein sequences of human and mouse GLC1A are >80% identical and mouse GLC1A is expressed in a pattern similar to that of human GLC1A (R. Swiderski and V. Sheffield, unpubl.). These data suggest that the mouse model organism may be useful in studying the human GLC1A gene and its role in the pathophysiology of glaucoma.

METHODS

BAC Screening

Bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clones containing the human GLC1A gene were identified by screening human BAC library pools (Research Genetics, Huntsville, AL) with a PCR-based assay. One microliter of BAC pool DNA was used as template in an 8.35-μl PCR reaction containing 1.25 μl of 10× buffer (100 mm Tris-HCl at pH 8.3, 500 mm KCl, 15 mm MgCl2); deoxynucleotides dCTP, dATP, dTTP, and dGTP (300 μm each); 1 pmole of each primer; and 0.25 units of Taq polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN). The primers used in the screening assay were specific for exon 3 of GLC1A (forward 5′-ATACTGCCTAGGCCACTGGA-3′, and reverse 5′-CAATGTCCGTGTAGCCACC-3′). Samples were denatured at 94°C for 5 min and incubated for 35 cycles at 94°C for 30 sec, 55°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 30 sec in a DNA thermocycler (Omnigene, Teddington, Middlesex, UK). After amplification, 5 μl of stop solution (95% formamide, 10 mm NaOH, 0.05% bromophenyl blue, 0.05% xylene cyanol) was added. Amplification products were electrophoresed on 6% polyacrylamide–5% glycerol gels at 50 W for ∼2 hr. After electrophoresis, gels were stained with silver nitrate (Bassam 1991). A BAC containing the mouse GLC1A ortholog was identified by screening the mouse 129 BAC library pools (Research Genetics, Huntsville, AL). Primers specific for exon 3 of the human GLC1A gene (forward 5′-TGGCTACCACGGACAGTTC-3′, and reverse 5′-CATTGGCGACTGACTGCTTA-3′) were used for a primary PCR-based screen as described above. The primary screen identified subpools of BACs that contained the mouse GLC1A gene. Filters blotted with the BACs in the subpools (Research Genetics, Huntsville, AL) were screened by hybridization with a digoxigenin probe using the Genius System hybridization kit (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN). Digoxigenin-labeled probe for hybridization was generated by PCR amplifying 50 ng of mouse 129 DNA in a 25-μl reaction containing 3.75 μl of 10× buffer; 1.5 μl of labeling dNTP mixture (1 mm dATP, 1 mm dCTP, 1 mm dGTP, 0.65 mm dTTP, and 0.35 mm of digoxigenin conjugated dUTP); 7.6 pmoles each of FWD and REV primer; and 1.25 units of Taq polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN). PCR reaction conditions were as described above. Hybridization conditions were as recommended by the manufacturer.

The human GLC1A cDNA sequence was used to select PCR primers that produced an amplification product of identical size when using both human and mouse genomic DNA as template. The amplification products were sequenced to confirm that they were from the human GLC1A gene and the mouse ortholog of this gene. The PCR primers were then used to screen both a human and mouse BAC library. Both human and mouse BACs containing the GLC1A gene were identified, subcloned into plasmids, and several clones covering each GLC1A gene were identified. These subclones were used to generate both human and mouse genomic GLC1A sequence.

Subcloning

The mouse and human BACs containing the GLC1A gene were digested with either EcoRI, AvaI, AccI, or BamHI and ligated into either pT7-blue (Novagen, Milwaukee, WI) or pUC19.

Sequencing

PCR products and BAC subclones were sequenced with fluorescent dideoxynucleotides on an Applied Biosystems (ABI) model 373 or 377 automated sequencer.

GLC1A CA Repeat Polymorphisms

The CA repeat polymorphism upstream of the GLC1A gene was PCR amplified with primers 5′-TTGAAATCAGCACACCAGTAG-3′ and 5′-GAGGCTGGGTGGGGCTG-3′, whereas the CA repeat polymorphism downstream of the GLC1A gene was amplified with primers 5′-TTCCTTCAGGTTGGGAGATG-3′ and 5′-GAGAGCACCAGGAGATGGAG-3′. The PCR reaction conditions were as described in the BAC-screening section. Allele frequencies for the upstream polymorphism are allele 1, 1.1%; allele 2, 2.2%; allele 3, 48.9%; allele 4, 1.1%; allele 5, 21.1%; and allele 6, 25.6%. Allele frequencies for the downstream polymorphism are allele 1, 25.3%; allele 2, 13%; allele 3, 60.3%; and allele 4, 1.4%.

Sequence Comparison

DNA sequences were aligned and contigs were formed using the Sequencher DNA analysis package (DNA Codes, Ann Arbor, MI). Putative enhancer and promoter elements were identified using the internet resource TESS (http://agave.humgen.upenn.edu/utess/) and the transcription factor-binding site data set TRANSFAC v. 3.2. The predicted protein sequence was analyzed with PROSITE, TMpred, NetOgly, and SignalP software packages available on the internet at http://expasy.hcuge.chsprot/prosite.html; http://ulrec3.unil.ch/software/TMPRED_form.html; http://genome.cbs.dtu.dk/services/netOGLYC/; http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/. Database searches for expression of the GLC1A gene used the program BLAST and the databases dbEST and NR available on the internet at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/cgi-bin/BLAST/nph-blast?Jform=0.

Northern Blot Analysis

Human multiple tissue Northern blots (Clontech, San Francisco, CA) were probed either with the entire human GLC1A cDNA sequence or with a section of exon 3 of the human GLC1A gene corresponding to codon 315 to the termination site. The probes were labeled with [32P]dCTP using Ready-To-Go DNA Labeling Beads (Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). Hybridization was for 16 hr at 42°C in 50% formamide, 5× standard saline citrate (5× SSC, 0.75 m sodium chloride, 0.075 m sodium acetate), 1× Denhardt’s solution, 20 mm phosphate buffer (pH 7.6), 1% SDS, 100 μg/ml salmon sperm DNA, and 10% dextran sulfate. Following hybridization, blots were washed twice at room temperature in 1× SSC, rinsed twice in 1× SSC/1% SDS at 65°C, and washed once in 0.1× SSC at room temperature. The stringency of the 65°C washes was raised to 0.1× SSC, 0.1% SDS, to confirm the specificity of the hybridization. Autoradiography was performed with Kodak XAR-5 film at −70°C with DuPont Cronex Lightning Plus intensifying screens (DuPont, Wilmington, DE).

Acknowledgments

We thank G. Beck and R. Hockey for their excellent technical assistance. This work was supported in part by the Carver Charitable Trust, National Institutes of Health grants EY10564, EY08905, EY02477, EY02162, and an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness (New York, NY).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

NOTE ADDED IN PROOF

After this manuscript was submitted, a related work was published. Adam et al. [1997. Hum. Mol. Genet. 6: 2091–2097] reported genomic sequences of the human GLC1A mutations and identified five new GLC1A mutations in French glaucoma families. Additionally, GLC1A RNA was shown to be expressed in four ocular tissues and two nonocular tissues by Northern blot analysis.

Footnotes

E-MAIL val-sheffield@uiowa.edu; FAX (319) 335-7588; E-MAIL edwin-stone@uiowa.edu; FAX (319) 335-7142.

REFERENCES

- Alward, W.L.M., J.H. Fingert, M.A. Coote, A.T. Johnson, S.F. Lerner, D. Junqua, F.J. Durcan, P.J. McCartney, D.A. Mackey, V.C. Sheffield, and E.M. Stone. 1998. Clinical features associated with mutations in the chromosome 1 open angle glaucoma gene (GLC1A). New Eng. J. Med. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bassam BJ, Caetano-Anolles G, Gresshoff PM. Fast and sensitive silver staining of DNA in polyacrylamide gels. Ann Biochem. 1991;196:80–83. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90120-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan GCK, Hess P, Meenakshi T, Carlstedt-Duke J, Gustafsson JA, Payvar F. Delayed secondary glucocorticoid response elements. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:22634–22644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jantzen K, Fritton HP, Igo-Kemenes T, Espel E, Janich S, Cato ACB, Mugele K, Beato M. Partial overlapping of binding sequences for steroid hormone receptors and DNaseI hypersensitive sites in the rabbit uteroglobin gene region. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:4535–4552. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.11.4535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn HA, Moorhead HB. Statistics on blindness in the model reporting area 1969-70. U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare Publication; 1973. . DHEW Publication no. (NIH) 73–427. [Google Scholar]

- Kubota R, Noda S, Wang Y, Minoshima S, Asakawa S, Kudoh J, Mashima Y, Oguchi Y, Shimizu N. A novel myosin-like protein (myocilin) expressed in the connecting cilium of the photoreceptor: Molecular cloning, tissue expression, and chromosomal mapping. Genomics. 1997;41:360–369. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leske MC. The epidemiology of open-angle glaucoma: A review. Am J Epidemiol. 1983;118:166–191. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortego J, Escribano J, Coca-Pradus M. Cloning and characterization of subtracted cDNAs from a human ciliary body library encoding TIGR, a protein involved in juvenile open angle glaucoma with homology to myosin and olfactomedin. FEBS Lett. 1997;413:349–353. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00934-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polansky JR, Fauss DJ, Chen P, Chen H, Lütjen-Drecoll E, Johnson D, Kurtz RM, Ma ZD, Bloom E, Nguyen TD. Cellular pharmacology and molecular biology of the trabecular meshwork inducible glucocorticoid response gene product. Ophthalmologica. 1997;211:126–139. doi: 10.1159/000310780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheffield VC, Stone EM, Alward WLM, Drack AV, Johnson AT, Streb LM, Nichols BE. Genetic linkage of familial open angle glaucoma to chromosome 1q21-q31. Nature Genet. 1993;4:47–50. doi: 10.1038/ng0593-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone EM, Fingert JH, Alward WLM, Nguyen TD, Polansky JR, Sunden SLF, Nishimura D, Clark AF, Nystuen A, Nichols BE, Mackey DA, Ritch R, Kalenak JW, Craven ER, Sheffield VC. Identification of a gene that causes primary open angle glaucoma. Science. 1997;275:668–670. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5300.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramani S. Protein import into peroxisomes and biogenesis of the organelle. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1993;9:445–478. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.09.110193.002305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunden SLF, Alward WLM, Nichols BE, Roklina TR, Nystuen A, Stone EM, Sheffield VC. Fine mapping of the autosomal dominant juvenile open angle glaucoma (GLC1A) region and evaluation of candidate genes. Genome Res. 1996;6:862–869. doi: 10.1101/gr.6.9.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tielsch JM. Blindness and visual impairment in an American urban population. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108:286–290. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070040138048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— . Therapy for glaucoma: Costs and consequences. In: Ball SF, Franklin RM, editors. Transactions of the New Orleans Academy of Ophthalmologists. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Kugler; 1993. pp. 61–68. [Google Scholar]