Abstract

Research question

We are looking at the process of structuring an integrated care system as an innovative process that swings back and forth between the diversity of the actors involved, local aspirations and national and regional regulations. We believe that innovation is enriched by the variety of the actors involved, but may also be blocked or disrupted by that diversity. Our research aims to add to other research, which, when questioning these integrated systems, analyses how the actors involved deal with diversity without really questioning it.

Case study

The empirical basis of the paper is provided by case study analysis. The studied integrated care system is a French healthcare network that brings together healthcare professionals and various organisations in order to improve the way in which interventions are coordinated and formalised, in order to promote better detection and diagnosis procedures and the implementation of a care protocol. We consider this case as instrumental in developing theoretical proposals for structuring an integrated care system in light of the diversity of the actors involved.

Results and discussion

We are proposing a model for structuring an integrated care system in light of the enacted diversity of the actors involved. This model is based on three factors: the diversity enacted by the leaders, three stances for considering the contribution made by diversity in the structuring process and the specific leading role played by those in charge of the structuring process. Through this process, they determined how the actors involved in the project were differentiated, and on what basis those actors were involved. By mobilising enacted diversity, the leaders are seeking to channel the emergence of a network in light of their own representation of that network. This model adds to published research on the structuring of integrated care systems.

Keywords: healthcare network, enactment of diversity, joint leadership, France

1. Introduction

Integrated care is presented as an appropriate response to the fragmentation of the healthcare sector, which leads to the inefficient use of resources, the redundancy or absence of care consultations, disruptions in patient care and scattered knowledge of patients [1]. The challenge lies in how to integrate a variety of actors and organisations, in order to coordinate caring for the patient beyond the many barriers that characterise this sector (institutional, professional, knowledge, regulatory, competence to intervene, etc.).

We are interested in the stage at which an integrated care system emerges. Such a system is a continuous process, “from the lowest level of informal contacts to the highest level, where a common authority is established as responsible for management and operational decisions” [1, p. 1], and which ends, in most cases, with the systems being recognised by the competent authorities (who then grant them public funding). This development phase is always a delicate balance [2], between public authority requirements and the individual aspirations of local actors, between the frameworks (often the result of regulation) that govern practices and the independent way in which the actors conceive their integration, and between the diversity of the actors and the integration of their interventions beyond institutional or professional barriers. This can lead to uncertainty where the project is concerned (and to the meaning to be assigned to the term ‘integration’), unclear leadership roles [3] and low participation levels, with the actors preferring to safeguard their professional independence [4].

The question we are asking is: how do the actors design integrated care systems in a context where the actors involved are diverse? We focus on the specific role played by the leaders who are driving this design process.

We will answer this question through a specific approach: the way in which the leaders enact and manage the diversity of the actors involved in order to succeed in designing an integrated care system.

We will then suggest a model for structuring an integrated care system in light of the enacted diversity of the actors involved.

This model explains how two leaders successively piloted this project, and we will show that each one operated in a different way, as they had a different understanding of what the diversity of the actors involved can bring to the design of a project. Through this process of diversity enactment (and not just diversity management), they determine how the actors involved in the project are differentiated, and on what basis those actors may be involved. Through this particular leader scheme of managing through enacted diversity, the leaders are seeking to channel the development of a network in light of their own representation of that network. We will discuss a particular form of leadership (joint leadership1) that these leaders create, when leading the design process for an integrated system in view of the enacted diversity of the actors involved.

The case study is a French case, and we will provide an overview of the specific features of the research field in section 4 (paragraph 4.1).

2. Theoretical framework structuring, innovation and diversity

In order to define the concept of integrated systems, we refer to Williams and Sullivan [1]. On the basis of various studies, they define these systems as based on “joint goals, shared or single management arrangements, joint commissioning, and joint arrangements for managing strategic and operational issues, and strategies for promoting integrated care.” [1, p. 3]. An integrated care system provides “a coordinated continuum of health services for a defined population” [5, p. 7]. Integrated care systems are based on a collaborative arrangement approach [4].

We are interested in the phase when an integrated care system develops, which is always delicate. The literature approaches this phase through different theoretical frameworks: the appropriate governance for structuring the integrated care system [3], key influencing factors [6], structuring emerging from the daily work on coordination [7], etc.

In our article, we will rely heavily on published research that analyses the structuring process as a process that switches between individual actions and structural factors, especially: the interplay between structure and agency [1], and the articulation between power, culture and structure [4].

This research pose different questions about the actors’ margin for manoeuvre when faced with the complexity of the context. That complexity is the result of two factors: the diversity of the actors, organisations and institutions that are stakeholders in the setting up of integrated care, and the relative weight of regulation in relation to the local aspirations of the actors. We ask questions about the actors’ ability to design an integrated care system that strikes a balance between diversity, local aspirations and the regulatory framework, and we question the relationship between innovation and the diversity of the actors involved to answer those questions.

According to Wihlman et al. [3, p. 2], an innovation in integrated care is defined as “a new set of behaviours, routines and ways of working that are directed at improving health outcomes, administrative efficiency, cost effectiveness or users' experiences and that are implemented by planned and coordinated actions.” The perception of change is defined in terms of a more or less in-depth calling into question of the rules, frameworks or standards [8] according to which the actors usually operate. These rules, frameworks or standards are of a diverse nature: professional, cognitive, institutional, regulatory, etc. Innovation then presumes to go beyond these frameworks to create new ones within a context of actor diversity.

The term ‘diversity’ is anchored in a set of thought-patterns that question the individual. Diversity is understood as the difference between individuals, in areas as varied as gender, culture, nationality, age, religion and education, etc. [9]. Milliken and Martins [10] identified eight types of diversity: ethnic or cultural diversity, gender, age, values and personality, education, functional and occupational diversity. The individual is also characterised by his or her personal, professional or institutional identity. We define the diversity of the actors as what is heterogeneous and different in terms of individual, social, cultural, cognitive and individual characteristics. We consider that this list of what creates difference is not exhaustive. It is in view of a specific management situation that the criteria around which the diversity of the actors is considered are taken into account and named. This position finds its meaning in our so-called interpretative perspective, which we will develop below.

Diversity enriches innovation as much as it disrupts it. Confrontation between individuals calls into question routines that provide a reassuring framework for action. The heterogeneity of the actors involved promotes conflict, difficulties in understanding and less social integration, which makes coordination between the actors a delicate process that may lead to costly organisational forms in cognitive [11] or political [9, 12] terms.

In order to remedy such issues, some research looks at training and cultural integration strategies to promote the assimilation of individuals within the organisation [13]. Conversely, other research looks at the appropriate structures [14] or tools [11] that enable innovation while promoting diversity. Certain authors specifically analyse discussion processes, and innovation is then the result of the development of a negotiated local order [15].

However, this research is based on a few premises that we intend to question. The first premise is to consider diversity as essentialist, namely consider that diversity is attached to the essence of the individual [16]. Differences are observed at a group level, and the individual, through his or her (dominant) characteristics, is supposed to behave like the rest of the group, outside his or her own aspirations or other characteristics. The second premise is to consider that, particularly in the healthcare field, the actors with whom integrated systems have to be designed are provided: “an organisation does not choose its own stakeholders. Instead, stakeholders, by necessity, choose to have particular stakes in the organisation's decisions” [5, p. 8].

On the contrary, we agree with certain authors, who are few in number, who consider that diversity is not an exogenous factor in the project, but a social and strategic construct of the organisation [17], which is the result of structural arrangements, of the way in which the organisation works, or of the way in which it views differences as affecting diversity and its management [18]. Diversity is not a natural category, but the product of social activity and interactions. It is no longer a question of managing diversity but of ‘doing diversity’ (Doing Gender, [17, p. 27]), and enacting differences between individuals; diversity is therefore the result of a construct that can create similarities and lack of similarity between individuals involved in an action. Diversity is only meaningful in relation to the action during which it is enacted [19].

We will answer both of our research questions in light of the way in which the actors enact diversity to innovate.

3. Methodology

Our research is moderately inductive and is based on a review of the published research that enables us to establish a framework for (but not to test) what we aim to observe and discuss on the ground and to develop theoretical proposals.

We have used the case study method [20], which enables us to answer questions of the ‘why’ and ‘how’ type and to contextualise the way in which the phenomenon studied unfolds, in order to suggest areas where generalisations can be made [20, 21].

Our research focused on a single case that we studied in depth as the quality and validity of results do not solely depend on the number of cases studied [22]. According to these authors, studying a single case enables the researcher to gain a detailed understanding of the history, as studied in context, and to therefore come up with “a good theory” [22, p.4]. What matters is being able to conduct a “careful study of a single case [so that to lead] researchers to see new theoretical relationships and question old ones” [22, p. 2]. The generation of new theoretical proposals is arrived at through working on “comparisons within the same organisational context” [22, p. 2].

Finally, our research focused on a single case, although we analysed that case on two levels: at the level of the way it was structured, examined in a longitudinal manner, and at the level of three innovations that represent three embedded case studies [23] and were analysed during the process. These innovations (a test, a fuller assessment and a working group known as a staff meeting) describe important moments in the gradual setting up of the healthcare network. Moreover, they were selected in view of their variety: a tool used by an actor (test) or by several actors (assessment), tools linked to the practising of medicine (test and assessment) or to the management structure (staff meeting).

The diversity of embedded cases and a comparative analysis of them enabled us to strengthen our notions of enacted diversity and of the enacted diversity management stance, together with our theoretical proposals [24].

The choice of case is therefore very important. We view the case that we have selected as exemplary [24] and close to the concept of an instrumental case [21]2, since this case was selected to examine our theoretical question regarding how to build an integrated system in light of the diversity of the actors involved.

Our theoretical proposals building combine multiple data collection methods [24]. The primary data were gathered during five sets of semi-directed interviews of around one hour (roughly one set per year, between 2002 and 2006), in the course of which we questioned between eight and 12 professionals (18 different actors): general practitioners, neurologists, geriatricians, speech therapists, a neuro-psychologist (the future network coordinator) and local authorities. The semi-structured interview guide was based on the following questions: “Tell me about how the healthcare network emerged?”; “How do you understand the involvement, or the arrival and departure of certain actors involved in the process?”; “How do you analyse the neurologist’s/coordinator’s [the process leaders] role?”. The primary data were recorded and transcribed in full. We also gathered secondary data (professional reviews, regulations, etc.).

The data were analysed according to the recommendations made by Miles and Huberman [25]: summary of the data, code words based on a table taken from published research supplemented by code words that emerged from the field study, analytical matrices, and ongoing cross-referrals between the practical and theoretical aspects throughout the study. The code words gathered from published research were (mainly) the following: actor, leader and diversity. Diversity is defined as explained above (i.e. as a difference), and codified in such a way as to account for the manner in which the actors create diversity (according to the interpretative perspective adopted by us). Our analysis has led us to emphasise the following emergent codes: (see paragraph 4.3 for an overview of the results, and the chart below):

diversity in terms of the institution and in terms of knowledge,

-

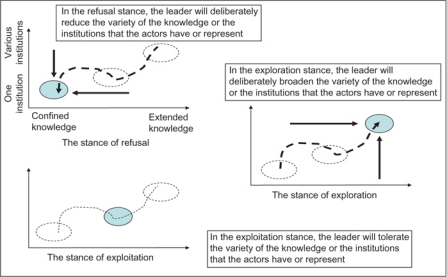

the three diversity management stances (refusal, exploitation and exploration);

When an actor does not integrate the diversity (in terms of knowledge or an institution) contributed by other actors, we call this a “diversity refusal stance”; this actor is acting according to the knowledge that they have or the institutions that they represent (and on which they base their actions); when an actor acts according to the diversity that exists at a point in time, without seeking to reduce it or, conversely, to broaden it, we call this a “diversity exploitation stance”; when an actor creates heterogeneity as the basis for his actions, and lets the actors express what differentiates them in terms of knowledge or institutions, we call this a “diversity exploration stance”.

processes of focus and expansion of the integrated system structuring, depending on whether the process is more or less open to diversity.

Chart 1 shows the different ways of building an integrated system from an enacted diversity standpoint. Each of the three figures represents a category of stance adopted to build diversity, drawn around two axes, each of which represents one of the dimensions for building diversity: the horizontal axis is an unbroken line between confined knowledge (or refusal of diversity) and diverse knowledge (or exploration of diversity); the vertical line is an unbroken line between the decision to favour a single institution (or refusal of diversity) and the decision to take various institutions into account (or exploration of diversity).

Chart 1.

The three diversity enactment stances.

The further the cursor moves to the left along the horizontal axis (knowledge axis) or towards the bottom on the vertical axis (institution axis), the more focussed the enactment process for the integrated system is said to be. To the contrary, the further the cursor moves to the right along the horizontal axis (knowledge axis) or towards the top on the vertical axis (institution axis), the more expansive the enactment process for the integrated system is said to be.

Following Yin [20], the four criteria for judging the quality of qualitative research based on case studies are: construct validity, internal validity, external validity and reliability.

About the construct validity, we have used different data sources (primary and secondary data), in order to increase confidence in our data. The data were encoded by a single researcher (the author), although different approaches were used to ensure that the construct was sound. Each of the three innovations was analysed separately, based on the encoded data, and that analysis enabled a “cross-case search for patterns” [24, p. 540], making emerge similarities and differences in structuring integrated health system through the enacted diversity. The analyses performed based on the encodings were shown to and discussed with a doctoral student, who was writing his thesis under our direction and who had a detailed knowledge of the field, and with one key informant (the network co-ordinator).

About the internal validity, we applied several approaches in order to generate plausible conclusions and achieve consistency in the results generated.We gathered additional primary data based on our observations as attendees, when we attended various working groups and staff meetings. This very close involvement in the actors’ discussions enabled us to understand how the actors built their own understanding of the healthcare network and its activities [26]. We went back over the ground covered on various occasions after the study period in order to complete our data and validate our analysis (principle of data saturation). We structured our article on three levels (or stages) of making emerge your theoretical proposals [24, 27]: overview of the factual data used (paragraph 4.2), overview of the contextualised intermediate theories (paragraph 4.3) and development of the structuring model through enacted diversity (Section 5), using four theoretical proposals that add to published research (section 6) based on a case that is considered as exemplary [21, 24, 28].

About the external validity, we have positioned our research in line with general theoretical (and not statistical) thinking. In order to specify the external validity of our research, we need to determine the kind of situation involved, namely: the construction of an organised system that brings together actors who belong to different organisations and who have not been very used to developing collective and co-ordinated working methods in the past, in order to execute an extremely ambiguous project successfully (the starting orders to improve the diagnosis and care of elderly people suffering from a cognitive disease were vague), within a relatively unstructured context (the health network concept is vague in itself, and is the basis for very different outcomes). These features define the how far the lessons drawn from the case can be generalised. We should specify that the issue of external validity involves creating and applying enacted diversity in order to perform this structuring process. Although we have identified that this enactment of diversity was achieved in terms of two dimensions (knowledge and institution) in our field, both these dimensions remain specific to the field studied. We can, however, generalise by saying that leaders may enact the diversity of the actors around dimensions that seem relevant to them, and on the basis of which they want to differentiate the actors from one another.

About the reliability of the research, we used several approaches in order to ensure that the research conducted could be replicated: an accurate description of the gathering, analysis, compilation and presentation of the data. Reliability is also a product of the researcher’s honesty regarding the research field: our position as a researcher in the field was explicitly stated [26]; we based ourselves on a few key informants (the two leaders and two doctors in particular, in view of their knowledge of the field or their experience of healthcare networks). Research feedback sessions were organised on a regular basis (in ad hoc meetings or during working sessions) to make sure our interpretations were correct.

4. Case study analysis

4.1. General overview of the case study

The French healthcare system is currently affected by two trends. The first trend is increasing government influence in the management and the organisation of the system (a Bismarckian model that is becoming increasingly Beveridgian), particularly by defining the conditions of access to general and specialist practitioners, by managing public hospitals and by imposing tight regulations on the private sector. The second trend is a desire to de-compartmentalise the healthcare and medico-social sectors, in order to make the patient's trajectory through the healthcare system easier (and to reduce the cost of that journey). “Strong fragmentations exist between medical services and social services, community-based and hospital-based services, healthcare professionals and family caregivers, as well as long-term and acute care” [29, p. 2]. Healthcare networks combine both those trends. The Government defines organisation and management methods for these networks through regulatory channels, encouraging healthcare professionals, healthcare institutions and patients to join them. Nonetheless, except for certain categories of care (cancer), the initiative for creating such networks remains overwhelmingly with professionals and local institutions [29]. During the case study period (2001–2006), the Government had defined what a healthcare network ought to be (co-ordination between healthcare professionals, who are the leading partners, and healthcare institutions regarding the patient healthcare plan), but had not yet issued more specific regulations about what a gerontology network ought to be. Among other things, this explains the various actors’ margins for manoeuvre.

The Memory Network (MN3) healthcare network currently brings together general practitioners and specialists (gerontologist, neurologist), other healthcare professionals (neuropsychologist, speech therapist, psychiatrist, and social worker), institutions (General Council, etc.), organisations (hospitals, retirement homes, rehabilitation centres, etc.) around the detection, diagnosis and care of cognitive disorders (CDs) in the elderly, in a medium-sized town. These CDs are cognitive deteriorations (Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, etc.). They are increasing rapidly among the elderly population. However, healthcare professionals experience difficulties in diagnosing these CDs, which they do not understand well; early diagnosis is nonetheless essential if one hopes to slow their progression. They also find it hard to design multi-disciplinary care programmes, as they are not very used to working in a coordinated and formal manner.

This type of integrated healthcare system is strongly encouraged by national and regional authorities, who have decreed different regulations as to the form of these systems (compliance with which is at least one condition of accessing public financing for those facilities) over the past few years: the healthcare network must encourage relationships between general medicine and hospital care (since the end of the 1990s and the 2004 law4, and the regulation of 2007 that defines gerontology networks).

The structuring that we studied covers a period stretching from late 2001 (when the project was launched) to early 2006, when the network, which had been operating on an informal basis for four years, was recognised by and received funding from the regional authorities.

4.2. Development of the care network analysed through three innovations

In 2001, a few general practitioners, a gerontologist and a neurologist had been discussing how to improve the diagnosis of elderly patients suffering from cognitive disorders.

Each actor nonetheless had very different views on the appropriate response, although they used the term ‘healthcare network’. As for the value of the network from the patients’ perspective, improvement in their care was not understood in the same way: the neurologist was mostly interested in improving the diagnosis of cognitive disorders; the general practitioner wanted help with detection and above all to have support in improving monitoring of the patient once the diagnosis had been confirmed; the gerontologists wanted to improve the way they monitored their patients throughout the healthcare process; the speech therapists were promoting their skills in order to make a greater contribution to the diagnosis and patient care; the neuropsychologists wanted to improve the patient's life through ‘memory workshops’. Where its value for improving their practices was concerned, the actors mentioned three visions of the network [30]: the network as a co-production area for new resources and integration processes, the network as an area in which to promote their professional expertise, the network as a ‘resource platform’, where certain actors might come to source knowledge and tools in order to improve their job performance in their respective workplaces. Lastly, some actors wanted to see the network financed by the regional authorities, which assumes that regulations had been adhered to, while others would have been satisfied with a mutual adjustment system [31] which is more flexible in respect of the regulations.

It is within this complex context that the neurologist piloted the design of the network in early 2002; the neurologist is the chairman of the legal structure that supports it; due to his profession (neurology), he places himself above the other medical professions according to an (unspoken) hierarchy in the medical institution.

4.2.1. The rapid detection test

The neurologist's representation of the network was as a purely medical system that would serve his practice and enables him to determine a CD diagnosis in a better and faster way when he received a patient referred by a colleague. He influenced the way the MN was structured so that the first tool created was a rapid detection test.

The test consisted of five words and of a drawing of a clock. The way the patient memorises the words or the way in which he or she draws the clock enable a general practitioner to differentiate between a CD and other illnesses with similar symptoms. This test, which was at times used by some doctors (albeit with variations), establishes a framework for all the doctors in the network to notify a potential CD, using the same language. It rationalises the information that doctors send to the neurologist.

To this end, the neurologist relied on the expertise of the general practitioners, and set aside other knowledge, such as that possessed by a neuropsychologist or a speech therapist. He did not want to involve other (professional or hospital) institutions, out of fear that discussion might lead to designing a network that was different from his own representation of it. He also sidelined some actors who were involved in the setting up of other healthcare networks, out of fear that the latter might discuss the value of this tool in terms of beginning to build the network.

General practitioners used the detection test quickly in their consulting rooms, which enabled them to refer their patient to the neurologist with more complete or standardised records than was previously the case, and so the network’s activities began.

4.2.2. The evaluation assessment

However, from early 2003 onwards, the neurologist wanted to continue directing the structuring of the network towards a more comprehensive tool, which adds a few extra diagnosis elements, with the same concern of receiving better information about cases, in order to determine his final diagnosis and his care strategy more efficiently. He suggested preparing an evaluation assessment, relying first and foremost on the restricted group of general practitioners that he had already gathered around him, and to whom he had already promoted his representation of the network.

At the same time, however, the network was looking for funding from the competent regional authority, which assumed that the network was indeed promoting a more multi-disciplinary vision and paying greater attention to follow-on care processes (socio-medical interventions once the diagnosis was determined).

The neurologist relied on his social network to begin the design: a speech therapist, in view of her knowledge and her institutional position (she was a hospital practitioner and the MN had to rely on the hospital to access funding); a neuropsychologist, in view or her multi-disciplinary understanding of diagnosis and evaluation, which completed his outlook, which he knew to be too focused on the neurological dimension.

However, during 2004, the neurologist restricted the arrival of new speech therapists; the latter tried to promote broadening the MN to include other illnesses (including orphan diseases), which went against the neurologist's representation of the network. Likewise, the latter could not call on the knowledge of a general gerontologist, who wanted to promote his specialist knowledge of CDs, in the hope of acting as an intermediary between the general practitioner handling the detection and the neurologist determining the diagnosis. However, the gerontologist’s intentions were in total conflict with the neurologist, who wanted to design a network that was oriented towards his practice and promoted his knowledge. The gerontologist was marginalised and withdrew from the network.

The neurologist was thus trying to innovate within boundaries (of the network) that he aimed to control: a tool that was legitimised by the neurologist, but with more of a medico-social orientation.

Designed in this way, the assessment is a more complete tool, supported by various actors (general practitioner, speech therapist, neuropsychologist and neurologist), and one which enables multi-disciplinary and coordinated interventions upstream and downstream of the patient care process.

4.2.3. Staff meetings

Both of these tools were designed during working sessions, called staff meetings, that brought together between eight and 10 people, nine or 10 times a year. When it was designed, the make-up of the staff meeting and the way in which the speakers were organised were controlled by the neurologist; the staff meeting thus appeared as a place where the actors could be familiarised with the neurologist's representation of the network. However, the members of the staff meeting, who had become increasingly diverse (see above), appeared unmotivated and did not attend staff meetings much in late 2004 and 2005. They wanted to do more work downstream of the patient care process and on new problems (taking care of the home carer, relationships with retirement homes, psychiatric care, etc.) as well as on the structure and management of the network; they were keen to formalise the role of a network coordinator, which was still at the development stage, in a better way. That network coordinator was expected to make patient-focused relationships between professionals easier. To some, the neurologist’s representation of the network seemed limited and did not allow the elderly person suffering from a CD to be really cared for.

Lastly, a majority of the actors wanted the network to be financed by the regional authorities, in such a way that they would benefit from resources to invigorate the network and extend its development. A request for funding was submitted, which assumed the presentation of a network project where the activities complied with the legal definition of healthcare networks (see footnote no. 6). From this, the idea that the structuring of the network should no longer be dominated by the neurologist emerged.

The neuropsychologist became the coordinator. She was championed by the neurologist, whose professional (importance of neurological knowledge) and institutional (chairman of the network) position she was not calling into question. She was even supported by the neurologist in preserving the aims of the network in the field of caring for and monitoring elderly people suffering from a CD5. Lastly, she confirmed the neurologist's general intention of seeking public funding.

The coordinator led the staff meetings and broadened their scope to include new work topics (training the carers, monitoring patient care, therapeutic prevention and education, training retirement home staff, etc.). She included new members who were sought out because of their knowledge (psychiatrist, social workers) and the institutions that they represented (municipal bodies, the General Council, a coordinating nursing home practitioner, etc.). Those people promoted these new MN activities. She encouraged the actors to co-produce their network, without forcibly referring to the neurologist/chairman. A funding request application was prepared during 2005, which was approved by the regional authorities.

In early 2006, the network was funded and was monitoring around 300 patients. The staff meeting had become a system for producing tools and knowledge and for evaluating and managing them. The discussions provided food for thought on how the MN activities should develop. It was finally a place that was conducive to encouraging multi-disciplinary and coordinated care practices. The management structure that was put in place balanced the role of the neurologist, who was the chairman and the guardian of a network that was dedicated solely to CDs in the elderly (and not a gerontology network) and the role of the coordinator, which retained an inherent multi-disciplinarity, and thus made meeting certain expectations expressed by competent bodies easier, in order to continue benefiting from public funding. Since then, the network has continued to be financed by the competent authorities and its recent (2008) external evaluation has shown to what degree it offers services that are rated positively by patients and the professionals involved.

4.3. Case study analysis

The case study analysis highlights three sets of results regarding the structure of the healthcare network in light of the enacted diversity of the actors involved.

4.3.1. Regarding the criteria for enacting diversity

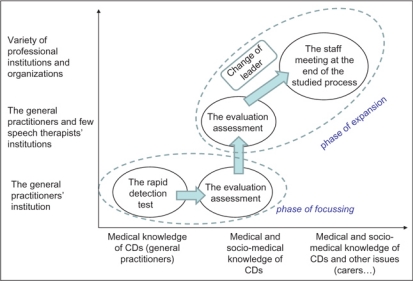

The case study shows that innovation is engendered by clearly defining the basis on which certain actors can contribute to that process in terms of knowledge and institutional viewpoints. Both leaders structured the network in light of the representation that they had of the system: the neurologist was attached to preserving his knowledge (of diagnosing cognitive disorders) and to his institution (the neurology). The coordinator paid more attention to multi-disciplinarity around the patient (variety of knowledge) and the bringing together of several institutions in one network in order to improve coordination around the patient.

The actors are thus viewed differently by the leaders, based on their knowledge and the institutions that they represent; therefore, whether they are integrated into the innovation process or not depends on their knowledge or on those institutions (see stance below). The leaders view the forces that have an influence on the creation of the network, and that may contribute to or disrupt their project as part of the actors’ knowledge or of the institutions that they represent.

4.3.2. Regarding the stances adopted towards enacted diversity

The neurologist understood diversity as a factor that might disrupt the organisation of his work and his hierarchical rank based on his knowledge; he feared a certain distortion of the project relative to his representation of it. When the assessment was established, he adopted a stance that was dismissive of diversity (diversity refusal stance), by relying solely on doctors who had strictly medical knowledge. When the assessment was prepared, he relied first and foremost on this small restricted group, acting according to a yardstick based on a register of acquired varieties, without seeking to create more diversity (diversity exploitation stance). He then broadened the diversity register, opening up to actors who added knowledge or who belonged to medico-social institutions, and relied on his social network in order to do this. He was acting according to the clearly defined exploration stance to innovate, within external boundaries (his representation of the network), which he intended to reaffirm; he was therefore seeking to control what emerged from relationships that were forming locally by sidelining certain actors.

The coordinator understood diversity as an enrichment for designing the network in light of her representation of it and for making it more compliant with the demands of public funding bodies (including actors and organisations from the medical and social field, acting upstream and downstream of the care process). She broadened the knowledge criterion to include new areas (psychiatry, social work) and then to other types of institutions (other professions such as psychiatry, local authorities, retirement homes, etc). She adopted an exploration stance in order to introduce new actors and co-produce the network representation with them.

4.3.3. Regarding the leaders’ roles

Two leader schemes succeeded one another while the healthcare network was being structured: the neurologist acted in order to focus the network around diagnosing CDs in the elderly, while the coordinator subsequently opened the system up to new actors who could work on taking care of patients and satisfy some of the regional authorities’ expectations. The first leader championed the second when he understood to what extent his stance could hinder the implementation of the process, although he could not call his own representation into question. We are therefore talking about joint leadership.

Chart 2 shows what we have observed in the case study, using Chart 1, which is a general chart, as a basis.

Chart 2.

The diversity enactment process in the MN case.

5. Theoretical proposal—proposal for developing a structuring model through a process of focus and expansion and using the enacted diversity of the actors

5.1. Proposal of a model of structuring an integrated care through the enacted diversity

The analysis of our results shows that the structuring we studied developed in two phases: focus (purpose of the network), and then expansion (integration of the various actors); this process was made possible by enacting the diversity of the actors involved and by the specific role played two leaders. We can develop an initial theoretical proposal regarding the model for structuring integrated care networks in light of the enacted diversity of the actors.

Theoretical proposal 1: Structuring an integrated healthcare system, through a process of focus and expansion and using the enacted diversity of the actors involved, is based on three factors: the criteria for enacting diversity, the stances adopted towards the diversity enacted and specific leadership.

We will elaborate on this model below so as to develop additional proposals. This model will be discussed with respect to the published research in part 6 (Discussion).

5.2. Structuring process through a process of focus and expansion

Our model describes situations where the diversity of the actors is construed by the leaders as factors that might possibly lead to a process that they could no longer control. In this instance, the action taken by the leaders consists in steering the structure through constraints. This guideline is borne out by the representation of the network that each leader conveys and that they wish to defend6. It is only once the target has been confirmed (through a focus process) that the leaders took action to open the structuring process to more actors. We have demonstrated through our case study that our model shows how each leader approaches the diversity of the actors involved (as a source of disruption or enrichment).

We develop the 2nd theoretical proposal:

Theoretical proposal 2: Structuring an integrated healthcare system through a process of focus and expansion, is a more prescriptive process, which the leaders resort to when they approach the diversity of the actors involved as a source of unpredictability that may lead to watering down their representation of the network.

We therefore believe that, in this context, going forwards by enacting diversity in order to innovate is an alternative to the prescriptive order. The leaders imposed their representation of the network on the actors, making their project apparent; we show that they were acting in this way by enacting and manipulating the diversity of the actors. We develop this concept of enacted diversity below.

5.3. The enacted diversity of the actors involved: a prescriptive structuring tools

The focus and expansion model is based on a specific tool: the enacted diversity of the actors involved and the leaders enacting the diversity of the actors in a way that promoted the development of the network in line with their representation of it.

First of all, this enactment enables the leaders to say on what basis they differentiate the actors7; it is also based on three stances that the leaders may adopt towards the (enacted) variety of the actors:

By adopting the diversity refusal stance, the leaders focus on certain specific characteristics of diversity (that they view as useful in light of their own representation), while denying others;

By adopting the diversity exploitation stance, the leaders are merely using a pre-acquired diversity register as a yardstick;

By adopting a stance that explores diversity, the actors are integrated into the innovation process according to the way in which the organisation believes that the factors that differentiate them can contribute to the action taken, in light of its representations.

By enacting the diversity of the actors, namely by defining on what basis (knowledge or institution) the actors participated in the development of an integrated system, the leaders attempted to set a framework for and to get around the usual power, cultural and structural systems that make up the healthcare field, contribute to its fragmentation and turn it into a battle field in order to maintain the independence of each actor.

We have developed the 3rd theoretical proposal as follows:

Theoretical proposal 3: Structuring an integrated healthcare system through a process of focus and expansion is achieved through enacting the diversity of the actors; this enactment process is based on two factors: the criterion (for differentiating the actors) and the stance (the degree to which the actors are integrated).

5.4. Joint leadership for implementing the structuring process through focus and expansion

Two leader schemes followed one another during the setting up of the healthcare network, which took place in a complex and pluralistic context [12], where power was scattered, goals were unclear (should they seek public funding?) and power could be exercised by different actors. We speak about joint leadership, which is defined by two characteristics. First, it takes form and develops over time. Second, it is the first leader, as the party providing the framework for the integration process, who guides the choice of the second leader. Indeed, the neurologist acting to set a framework for the network on the question of CD diagnosis in the elderly, then he has chosen and legitimated the coordinator (second leader) who has opening the network up to new actors in order to work on patient care and satisfy certain expectations held by the regional authorities. This joint leadership process allows the first leader to safeguard his professional identity (interest in Alzheimer's disease), while continuing to take part in the process of structuring the system indirectly, by naming and championing the second leader.

We can deduce from the case study that this joint leadership is based on two factors: the capabilities of each leader and their ability to articulate (or ‘hand over’) the succession between the actors.

Regarding the capabilities of the actors, their ability to manipulate the actors’ diversity is a particular form of their personal managerial capacity. And each of the leaders played on a certain formal position to legitimise the way they handled the diversity of the actors and thus impose their representation of the network: the neurologist relied on an informal hierarchical structure of medical knowledge, which puts neurological knowledge above other knowledge when it comes to diagnosing CDs in an elderly person. For example, it is this position ‘at the top’ that enabled him to organise and influence discussions during the working meetings on the different tools (test and assessment). The coordinator relied on a hierarchical structure that was being established, as her managerial position made her accountable to the actors for the demands of the competent bodies, in order to impose her representation of the network and enable its structure to evolve towards greater multidisciplinarity and towards taking the demands of the competent bodies into account.

Where the articulation of the leaders is concerned, the case study shows that the timing and the arrival of the second leader were crucial for maintaining this joint leadership. Indeed, there was an interesting critical moment around late 2004/early 2005, when the stance of the neurologist, which undoubtedly contributed to giving the doctors tools to make their detection practices easier, and enabled the neurologist to maintain his representation, led to: a decrease in the motivation of certain actors to whom the network was no longer of interest; a failure to have the network funded by the regional authorities, as it did not comply sufficiently with multi-disciplinary thinking and with the integration of activities throughout the care process (and not only upstream). It was in fact the succession of these two leaders, recognised as such, and with the first championing the second, that enabled this critical moment to be faced up to.

We have developed the 4th theoretical proposal as follows:

Theoretical proposal 4: Structuring an integrated healthcare system through a process of focus and expansion is achieved through specific leadership called joint leadership, which is based on: leaders playing on a formal position to legitimise the way they handle the diversity of actors and impose their representations of the system; leadership evolving when the first leader acts as championing the second one.

6. Discussion

We will discuss our theoretical proposals in light of the published research and so demonstrate the contribution made by our research.

6.1. About the structuring process through a process of focus and expansion

Structuring an integrated system is a process that switches between the variety of the actors involved, local aspirations and structural constraints [1] and is therefore based on a process of negotiation between the actors, in which constraints and actions are interpreted in light of common aims [3] and which ends in compromise. Thus, Williams and Sullivan [1] note that “the management of integration is more a process of deliberation and negotiation between local stakeholders than one of ideology and prescription” [1, p. 10]. Contrary to that, our model rests on interplay between action and structure which is not based on mechanisms that make sense, but which is in line with a prescriptive process (in line with the representations of the network that each leader wishes to defend).

For Williams and Sullivan [1], such processes of negotiation are made possible because of a lack of clarity in the meaning of the term ‘integration’, a certain flexibility of national and local structural arrangements and the variety of the actors' expectations. However, gathering actors around a vague term that is understood differently is likely to lead to a weak consensus [15], which only allows action to be produced with difficulty. Moreover, such processes can lead to “time-consuming process of constant negotiation between different interets with unpredictable outcomes” [1, p. 7]. Our focus and expansion model offers a course of action according to which the leaders have tried to avoid both a vague consensus and long periods of negotiation, by advancing step by step, first by restricting the number of actors involved in stabilising the first stage of the structuring process, and then opening the process to more diverse actors, once the leader has channelled the type of network in light of his representation of that network.

In addition, our model views the structuring process as a process between action and structures, which not only consist of the structures studied by Williams and Sullivan, but of structural arrangements [33], i.e. that are of a professional and institutional nature, on which they will rely to focus the structure.

6.2. About the enacted diversity

The enacted diversity of the actors as a structuring tool is based on the different way in which published research views diversity.

Diversity is not a resource of which the organisation can take advantage to act [34], but a tool created by the leaders to manage their project; they do therefore not take action in order to manage diversity, we consider that they manage (enact) diversity in order to act [19].

This tool has a relational and cognitive dimension [35]. We would add that the tool has a political dimension [36]. The leader presents and legitimises the diversity choices and the representations of the action that he has in order to act; he makes his project visible. This presentation is all the more critical in that the setting up of innovative systems disrupts acquired limits, and that the environment in which the action takes place is complex and fragmented.

The action organised is always a co-ordination process (or even a dialogical process) between individual and collective action [37]. Collective influence has often been studied in order to explain individual decisions or actions. In contrast, our case study allows us to highlight how an actor intends to act ‘outside’ the complex context created by the variety of the actors, manipulating this context by manipulating (creating) the diversity of the actors and so imposing his individual view of what collective action should be at critical moments [38].

Moreover, the coordination of the three stances over time reveals a ‘controlled’ management of complexity. The neurologist and then the coordinator progressively introduced the actors, explaining why they were being called upon. Through their stances, they expressed and set the framework for prescriptive relationships with certain actors whom they called upon to design the healthcare network.

The process of structuring an integrated healthcare system is therefore complex, given the diversity of the actors, and the process of building diversity is similar to a sense-making process in such cases [39]. The pilots tend to reclaim the complexity of their environment by defining the basis for differentiating the actors, thereby conditioning their behaviour (albeit on a partial basis). By defining the dimensions of the enacted diversity and by acting through one of the three diversity stances, the pilots develop the direction that the action must take; it is then up to the actors to act and take part in the sense-making process through their responses. For Weick [39], this is a way of reclaiming part of the complexity created by the implementation action. However, our research offers additional understanding, by revealing how that sense-making is enacted, and therefore emphasising the different ways in which these pilots approach the complexity of their actions. The sense-making process then relies on two factors. The first factor relates to an interpretative matrix aimed at understanding what makes something complex; that assessment matrix is based on the two dimensions of construction and diversity (in our case); the pilots therefore envisage the forces that influence the creation of the network, and that may contribute to or disrupt their project, as included in the actors’ knowledge or in the institutions that they represent. They therefore enact the direction of the action by enacting diversity in terms of knowledge and institution. The second factor relates to an action register in terms of complexity. Weick [40] then evokes the idea of ‘requisite variety’, of a fair variety in light of the complexity of the environment. The organisation must achieve a variety that is at least as broad as that of its environment, in order to respond to the external variety of that environment. The diversity exploitation and exploration stances are two action registers for taking such action. However, in the case of the diversity refusal stance, we highlight another action register, when the organisation (i.e. the leader in our case) reduces the complexity of its environment by decreasing the variety of the actors with whom it wants to interact.

6.3. About the joint leadership

In complex and pluralistic contexts, published research has highlighted two appropriate forms of leadership: a constellation of leaders [12], where different leaders share the general leadership role, acting in a united manner, in harmony with the other actors (close to the notion of a continuous and flexible leadership [29]), and dispersed leadership [41], where different actors act as leaders in an uncoordinated way and at different levels of an organisation, pursuing their own interests, and very often without having been identified as leaders.

Our case study distinguishes itself from the model of ‘dispersed leadership’, because both leaders were clearly percieved as such by the actors. It also enables us to take a fresh look at the constellation of leaders and we talk about joint leadership. However, contrary to [29], which argues that “the leadership was also tailored to the various phases of the process” [29, p. 8–9], our case shows an integration process according to which the process is supported and moulded by the leaders and their choices.

Regarding the capabilities of the actors, Mur-Veeman, Eijkelberg and Spreeuwenberg [4] observe that the construction of an integrated facility “does not rely on formal positions but rather on personal managerial capacities” [4, p. 151]. The ability to manipulate the actors’ diversity is a particular form of this personal managerial capacity that Mur-Veeman, Eijkelberg and Spreeuwenberg [4] evokes. In contrast, we believe that each of the leaders played on a certain formal position to legitimise the way they handled the diversity of the actors and thus impose their representation of the network (legitimation derived from an informal hierarchical structure of medical knowledge, or derived from the formal structure of the network, in our case).

This particular form of leader scheme management succeeded in avoiding the limitations of prescription-based approaches, which may discourage the actors involved, through a system of joint leadership, where both leaders positioned themselves and adapted over time, and where the second leader modified the choices made by the first, without calling them into question.

7. Conclusion

The emergence and stabilisation of integrated care systems are delicate processes and published research has often called into question the factors that may contribute to promoting, or conversely, to disrupting this phase [6, 4] or the negotiation and compromise processes underlying the structure. In contrast, we are proposing a model that describes situations where the leaders act in a prescriptive manner, given the way in which they understand the contribution that the diversity of the actors involved makes to the structuring process. This model is based on an analysis of the leaders’ behaviour in terms of the enacted diversity of the actors, and is based on three factors: enacted diversity, three stances for viewing the contribution of diversity to the process and the specific leadership role played by those in charge of the structuring process. By mobilizing enacted diversity, the leaders are seeking to channel the emergence of a network in light of their own representation of that network. We intend to continue our study of the integrated system structuring process in order to add value to our model.

8. Reviewers

Peter Berchtold, PD, Director of the College for Management in Healthcare, Bern, Switzerland

Yves Couturier, M.s.s. PhD, Chaire de recherche du Canada sur les pratiques professionnelles d'intégration de services en gérontologie, Institute universitaire de gériatrie, Université de Sherbrooke, Canada

Ali Smida, PhD, Professor, University of Paris 13. Director of the Master “Health Care and Social Management”, France

Footnotes

By ‘joint leadership’ we mean a form of leadership which evolves over time through the successive entry of actors, with each actor changing or building on the leadership established by the previous actor, but without calling the former into question.

This is not an intrinsic case [21]; an intrinsic case aims to provide a better understanding of this particular studied case situation.

MN—Memory Network; the name has been disguised.

Definition of a healthcare network as enacted in French law. “The aim of healthcare networks is to promote access to care, co-ordination, continuity or inter-disciplinarity of patient care, particularly care that is specific to certain population groups, illnesses, or activities that are particular to certain population groups, illnesses or types of patient care. Health networks provide care that is adapted to the needs of the patient, adapted at the level of healthcare education level, prevention, diagnosis and care” (Art. 84, French Public Health Code of 04.03.2002).

Indeed, during this period, other networks that were much more focused on gerontology were set up in France, namely networks whose aim was to coordinate professionals and institutions around the care of an elderly patient (regardless of whether that patient was said to be suffering from dementia). The competent authorities then drew up a circular defining what a gerontology network should be. The coordinator was therefore acting in such a way as to open up the MN to concerns that were of a more socio-medical nature (compared with the neurologist's medical vision), while maintaining a focus on the elderly person suffering from dementia.

The neurologist's representation is of a network that serves his practice, on a more individualistic basis (close to a social peer network) [32]. The coordinator’s representation is of a network that serves the practices of various actors and provides more encouragement a new organisational system, which is focused on a collective and shared benefit [32].

In the case study, two criteria were applied by the leaders: knowledge and institutions. Actors are therefore integrated into the healthcare network structuring process in light of their knowledge and of the institutions that they belong to.

References

- 1.Williams P, Sullivan H. Faces of integration. International Journal of Integrated Care [serial online] 2009 Dec 22; doi: 10.5334/ijic.509. Available from: http://www.ijic.org. URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-100751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hardy B, Mur-Veeman I, Steenberger M, Wistow G. Inter-agency services in England and the Netherlands, a comparative study of integrated care development and delivery. Health Policy. 2009;48:87–105. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(99)00037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wihlman U, Lundborg C, Axelsson R, Holmtröm I. Barriers of inter-organisational integration in vocational rehabilitation. International Journal of Integrated Care [serial online] 2008 Jun 19;8 doi: 10.5334/ijic.234. Available from: http://www.ijic.org. URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-100476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mur-Veeman I, Eijkelberg I, Spreeuwenberg C. How to manage the implementation of shared care; a discussion of the role of power, culture and structure in the development of shared care arrangements. Journal of Management in Medicine. 2001;15(2):142–55. doi: 10.1108/02689230110394552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Savage G, Taylor R, Rotarius T, Buesseler J. Governance of integrated delivery systems/networks: a stakeholder approach. Health Care Management Review. 1997;22(1):7–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eijkelberg I, Spreeuwenberg C, Mur-Veeman I, Wolffenbuttel B. From shared care to disease management: key-influencing factors. International Journal of Integrated Care [serial online] 2001 Mar 1;1 doi: 10.5334/ijic.22. Available from http://www.ijic.org. URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-100264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petrakou A. Integrated care in the daily work: coordination beyond organizational boundaries. International Journal of Integrated Care [serial online] 2009 Jul 9;9 doi: 10.5334/ijic.325. Available from http://www.ijic.org. URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-100567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Norbert A. L'innovation ordinaire. [the ordinary innovation]. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bassett-Jones N. The paradox of diversity management, creativity and innovation. Creativity and Innovation Management. 2005;14(2):169–75. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milliken F, Martins L. Searching for common threads: understanding the multiple effects of diversity in organizational groups. Academy of Management Review. 1996;21(2):402–34. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carlile P. A pragmatic view of knowledge and boundaries: boundary objects in new product development. Organization Science. 2002;13(3):442–55. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denis JL, Lamothe L, Langley A. The dynamics of collective leadership and strategic change in pluralistic organisations. Academy of Management Journal. 2001;44(4):809–37. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kossek E, Lobel S, Brown J. Human resource strategies to manage workforce diversity—examining the business case. In: Konrad A, Prosad P, Pringle J, editors. Handbook for diversity. Chapter 2. London: Sage; 2006. pp. 53–74. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tushman M, O’Railly C. Ambidextrous organizations: managing evolutionary and revolutionary change. California Management Review. 1996;38(4):8–30. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turcotte MF, Pasquero J. The paradox of multistakeholder collaborative roundtables. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science. 2001;37(4):447–64. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Litvin DR. The discourse of diversity: from biology to management. Organization: Discourse and Organization. 1997;4(2):199. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Omanovic V. Perspectives on diversity research. In: Leijon S, Lillhannus R, Widell G, editors. Reflecting diversity—viewpoints from Scandinavia. Sweden: BAS Publishers; 2002. pp. 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janssens M, Zanoni P. Many diversities for many services: theorizing diversity (management) in service companies. Human Relations. 2005;58(3):311–40. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grenier C. Le réseau de santé: une lecture constructiviste par la notion de gouvernance conceptive. [The healthcare network: a constructivist understanding through the notion of governance based on enacted diversity]. Journal d’Economie Médicale. 2009;27(1):273–89. [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yin RK. Case study research—design and methods. In Applied Social, Research Methods Series—volume 5. CA: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stake RE. 2000 case studies. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1989. pp. 435–54. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dyer W, Wilkins A. Better stories, not better constructs, to generate better theory: a rejoinder to Eisenhardt. Academy of Management Review. 1991;16(3):613–9. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Musca G. Une stratégie de recherche processuelle: l’étude longitudinale de cas enchassés. [A process driven research strategy: the longitudinal study of embedded cases]. Revue Management. 2006;9(3):145–68. [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eisenhardt K. Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review. 1989;14(4):532–50. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miles M, Huberman A. Analyse des données qualitatives—recueil de nouvelles méthodes. [Analysis of qualitative data—summary of new methods]. Bruxelles: De Boeck University; 1991. [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yakura E. Charting time: timeless as temporal boundary objects. Academy of Management Journal. 2002;45(5):956–70. [Google Scholar]

- 27.David A. Etudes de cas et généralisation scientifique en sciences de gestion. [Case studies and scientific generalization in management sciences]. Internationale de Management Stratégique (AIMS)Actes du XIIIème Conférence Annuelle de l'Association. 2004 Juin; Le Havre. [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bouty I. Interpersonal and interaction influences on informal resource exchanges between R&D researchers across organizational boundaries. Academy of Management Journal. 2000;43(1):50–65. [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Stampa M, Vedel I, Mauriat C, Bagaragaza E, Routelous C, Bergman H, et al. Diagnostic study, design and implementation of an integrated model of care in France: a bottom-up process with continuous leadership. International Journal of Integrated Care [serial online] 2010 Feb 18;10 Available from: http://www.ijic.org. URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-100748. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grenier C. Proposal of a model of actionable knowledge in distributed networks of professional actors, European Academie of Management (EURAM) Annual Conference. 2005 May 4–7; Munich. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mintzberg H, Glouberman S. Managing the care of health and the cure of disease—Part II: Integration. Health Care Management Review. 2001 Winter;1(26):72–86. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200101000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rey B, Perrier L, Chauvin F. Les apports de concepts économiques d’équipe et de groupe pour l’évaluation des réseaux de soin. [The contribution of economic team and group concepts for evaluating care networks]. Journal d’économie médicale. 2001;19(5–6):381–89. [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giddens A. The constitution of society. UK: Cambridge Polity Press in Association with Basil Blackwell; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ely R, Thomas D. Cultural diversity at work: the effects of diversity perspectives on work group processes and outcomes. Administrative Science Quartely. 2001;46(2):229–74. [Google Scholar]

- 35.David A. Outils de gestion et dynamique du changement. [Managerial tools and chance dynamics]. Revue Française de Gestion SeptߝOct. 1998;31(158):44–59. [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Broussard V, Maugeri S. Du politique dans les organisations—sociologies des dispositifs de gestion. [Politics in organisations—sociologies of managerial tools]. Paris: L’Harmattan; 2003. [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koenig G, Smida A. Introduction. La dialogique de l’individuel et du collectif dans le processus décisionnel. [Introduction. The dialogic between individual and collective in decision-making process]. Revue Economies et Sociétés, série Economie de l’entreprise. 2002;12(5):649–54. [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grenier C. L'organisation créatrice de contrainte paradoxale pour agir dans un environnement complexe—une relecture du rôle de la contrainte. [the organization enacting paradoxal constraints for managing complex context]. Revue Française de Gestion MayߝJune. 2003;144:83–103. [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weick K. Making sense of the organizations. Malde: Blackwell Publishers; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weick K. Organizational culture as a source of high reliability. California Management Review. 1987;29(2):221–33. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chreim S, Williams BE, Janz L, Dastmalchian A. Change agency in a primary health care context: the case of distributed leadership. Health Care Management Review. 2010;35(2):187–99. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0b013e3181c8b1f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]