Abstract

Cognitive impairment, including dementia, is a common but poorly recognized problem among patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), affecting 16–38% of patients. Dementia is associated with high risks of death, dialysis withdrawal, hospitalization, and disability among patients with ESRD; thus, recognizing and effectively managing cognitive impairment may improve clinical care. Dementia screening strategies should take into account patient factors, the time available, the timing of assessments relative to dialysis treatments, and the implications of a positive screen for subsequent management (for example, transplantation). Additional diagnostic testing in patients with cognitive impairment, including neuroimaging, is largely based on the clinical evaluation. There is limited data on the efficacy and safety of pharmacotherapy for dementia in the setting of ESRD; therefore, decisions about the use of these medications should be individualized. Management of behavioral symptoms, evaluation of patient safety, and advance care planning are important components of dementia management. Prevention strategies targeting vascular risk factor modification, and physical and cognitive activity have shown promise in the general population and may be reasonably extrapolated to the ESRD population. Modification of ESRD-associated factors such as anemia and dialysis dose or frequency require further study before they can be recommended for treatment or prevention of cognitive impairment.

Keywords: aging, cognitive impairment, dementia, ESRD

Cognitive disorders have long been recognized as a complication of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and its treatment; yet guidelines for the detection, prevention, and management of these disorders are lacking. Evidence is mounting that cognitive impairment is common among ‘adequately’ dialyzed patients, and that it may in turn affect ESRD management and outcomes in several adverse ways. This review outlines the rationale and tools for assessment of cognitive function and provides recommendations for the management of cognitive impairment and dementia among adults with ESRD.

DEFINITION OF TERMS

Dementia is a state of persistent and progressive cognitive dysfunction characterized by impairment in memory and at least one other aspect, or domain, of cognitive function, such as language, orientation, reasoning, attention, or executive functioning, the cognitive skill necessary for planning and sequencing tasks.1 The impairment in cognitive function must represent a decline from the patient’s baseline level of cognitive function and must be severe enough to interfere with daily activities and independence. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia in the general population, whereas vascular dementia, either alone or in combination with Alzheimer’s disease, is the second most common form of dementia in the United States.2 Dementia associated with Parkinson’s disease and other dementia syndromes account for the remaining 10–20% of dementia cases. Dialysis dementia is a term used to describe a rapidly progressive form of dementia, now considered rare, associated with aluminum toxicity in ESRD patients.3

Mild cognitive impairment is the most common terminology used to describe cognitive impairment beyond that associated with normal aging, but not crossing the threshold for dementia. Among elderly patients with mild cognitive impairment in the general population (as variously defined), the annual conversion rate to dementia ranges from 5 to 20%;4,5 therefore, these patients merit close follow-up.

Delirium is a syndrome of cognitive impairment characterized by inattention and altered consciousness attributable to a medical condition, medication side effect, or intoxication.1 In contrast to dementia, delirium develops over a short period of time and its course is often fluctuating (Table 1). Delirium and dementia often coexist, although the nature of their relationship is complex, and this may contribute to difficulty in distinguishing between these disorders. The classic descriptions of uremic encephalopathy and dialysis disequilibrium are of delirium syndromes attributed to retention of as yet unidentified uremic solutes and brain edema during dialysis, respectively.6,7 Earlier initiation of dialysis and the use of preventative measures for dialysis disequilibrium seem to have reduced the incidence of these syndromes, or at least their most severe presentations. In small studies, temporal fluctuations in cognitive function have been identified among hemodialysis patients, suggesting that subacute forms of these syndromes may exist.8,9 Whether patients with these temporal fluctuations in cognition are at higher risk for chronic or progressive cognitive impairment is not clear. Nevertheless, the development of delirium, regardless of its cause, in a patient with ESRD should heighten suspicion for underlying dementia.

Table 1.

Differentiating features of dementia, delirium, and depression

| Feature | Dementia | Delirium | Depression |

|---|---|---|---|

| Onset | Insidious | Acute | Acute or insidious |

| Course | Progressive | Fluctuating | Stable or fluctuating |

| Duration | Months to years | Days to months | Months to years |

| Consciousness | Intact except in advanced dementia | Altered | Intact |

| Complaints of memory loss | Variable | Absent | Usually present |

| Psychomotor change | Usually normal until advanced | Increased or decreased | Normal or decreased |

| Reversibility | Rarely | Usually | Usually |

IMPORTANCE OF ASSESSING COGNITIVE FUNCTION IN PATIENTS WITH ESRD

Dementia is common but poorly recognized

The prevalence of cognitive impairment, as assessed using neuropsychological tests among patients with ESRD, ranges from 16 to 38% depending on the sample and the definition of impairment.10–16 These rates are approximately threefold higher than the age-matched general population and substantially higher than the reported prevalence rate of dementia based on Medicare claims data,17 suggesting that nephrologists, similar to primary care physicians, are poor at recognizing and documenting dementia. For example, in two studies, <15% of ESRD patients with cognitive impairment had chart documentation.11,12 Further, subjective complaints of confusion and ESRD clinical performance measures are not highly correlated with the presence of cognitive impairment in ESRD patients.16,18 Thus, periodic screening is needed to accurately identify patients with cognitive impairment in order to improve their clinical care.

Cognitive impairment complicates ESRD management and contributes to poor outcomes

Why should busy nephrologists spend time assessing cognitive function, especially when the available treatments for dementia and more mild cognitive impairment have modest efficacy, at best? First, if cognitive impairment is not recognized, then potentially reversible causes of impairment, such as delirium or depression, cannot be identified and treated. Second, cognitive impairment may interfere with capacity for self-care and informed decision-making. For example, cognitive impairment may hinder adherence with the complex regimens often prescribed to patients with ESRD, increase the risk of adverse drug events, and impair informed decision-making surrounding issues such as preemptive vascular access placement and ESRD treatment options.19–21 Indeed, the high burden of cognitive impairment may explain, in part, why ESRD clinical performance targets have been so difficult to achieve. Third, dementia increases the risk for poor outcomes, including disability, hospitalization, withdrawal from dialysis, and death,17,22–25 and increases the cost of care. The clinical significance of cognitive impairment not meeting criteria for dementia has not been fully elucidated, although some evidence suggests that it may also be associated with poor outcomes.12 Fourth, a definitive diagnosis of dementia may provide an opportunity to define goals of care and facilitate end-of-life care planning before the disease becomes advanced. Fifth, although the available pharmacological therapy for dementia may have modest efficacy, newer treatments currently under development may prove even more successful in slowing disease progression. Thus, identifying dementia or severe cognitive impairment may lead to the institution of supportive care measures that improve outcomes and reduce disease burden.

WHO IS AT RISK FOR COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT AND DEMENTIA?

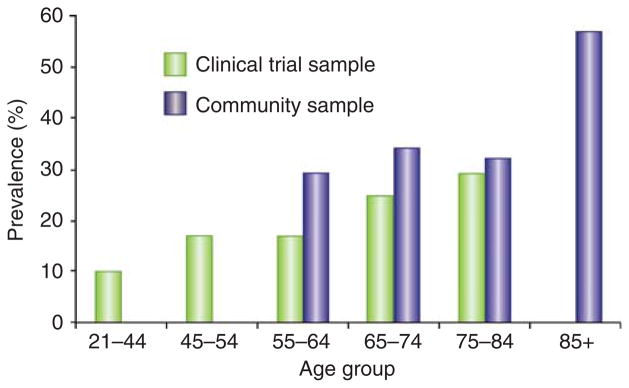

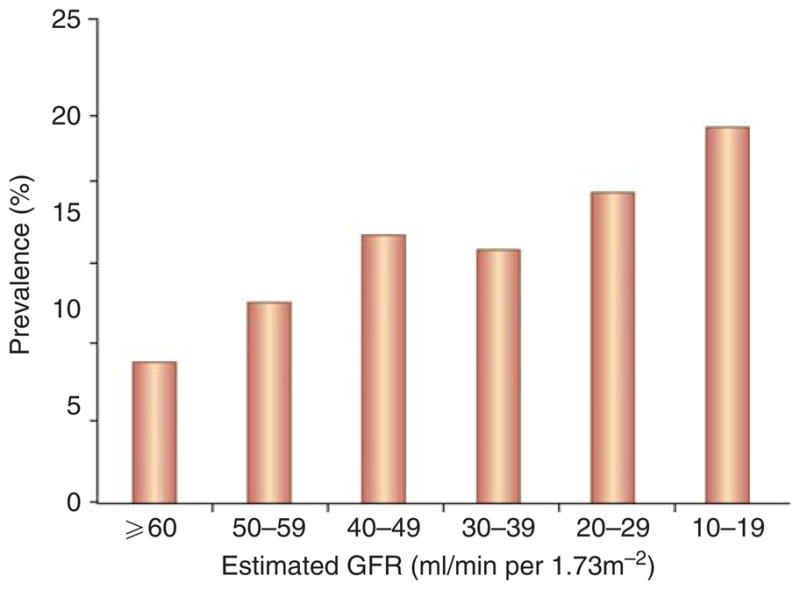

Similar to the general population, a dementia diagnosis is more common among the elderly, women, and non-white patients with ESRD, and less common among patients receiving peritoneal dialysis and transplant recipients, possibly reflecting patient selection and ascertainment bias.23,25 Advanced age is a major risk factor for dementia and cognitive impairment—30–55% of ESRD patients over the age of 75 years have cognitive impairment based on neuropsychological testing (Figure 1).11,15 Recognition of the burden of impairment in this age group is essential for effective management of ESRD comorbidities. The prevalence of cognitive impairment ranges from 10 to 30% among young or middle-aged patients with ESRD (Figure 1); therefore, screening strategies based only on age may miss a significant fraction of ESRD patients with clinically important cognitive impairment. Cognitive decline begins well before the development of ESRD, such that prevalence rates of dementia and cognitive impairment among older individuals with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) approximate those seen in patients with ESRD (Figure 2).26–30

Figure 1. Prevalence of cognitive impairment among patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) by age group.

Note: The clinical trial sample consisted of 383 hemodialysis patients participating in the Frequent Hemodialysis Network Trials. Cognitive impairment was defined as a Modified Mini-Mental State Exam score <80 (ref. 15). The community sample consisted of 374 hemodialysis patients in Minnesota. Cognitive impairment was defined according to performance on a neuropsychological battery.11

Figure 2. Prevalence of cognitive impairment among 23 405 US adults, according to estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR).

Data are adapted from Kurella Tamura et al.30

The neuropathology of cognitive impairment and dementia in ESRD is unknown, although several lines of evidence indicate that cerebrovascular disease may have a prominent role. The vascular beds of the brain and kidney have similar anatomic and hemodynamic features; these observations have led to the speculation that cognitive impairment and CKD (including microalbuminuria) are reflections of vascular injury in different end organs (Figure 3). Brain magnetic resonance imaging among unselected patients with CKD and ESRD demonstrates a large burden of large vessel stroke, small vessel stroke (lacunes), and white matter lesions (resulting from small vessel ischemia).31–35 In prospective studies, CKD independently predicts stroke and cognitive decline,26 and cerebral small vessel disease independently predicts risk for ESRD among patients with diabetes,36 suggesting that CKD and cognitive impairment share a common pathogenesis. Among patients with CKD and ESRD, stroke is a major risk factor for cognitive decline and dementia, and in contrast to the general population, the incidence of vascular dementia may approach or exceed the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease.27,37

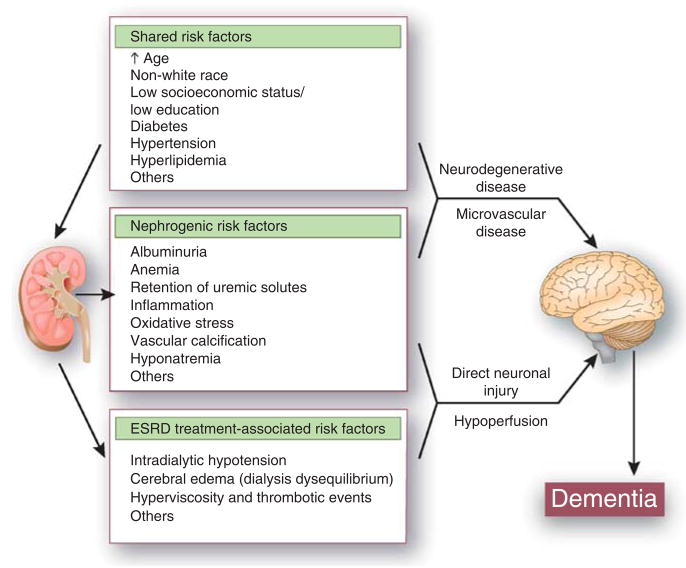

Figure 3.

Proposed mechanisms of dementia in end-stage renal disease (ESRD).

Yet, this may be an oversimplification, as there is considerable overlap in risk factors, clinical features, and radiographic and neuropathological findings between Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia, and it is now recognized that vascular lesions may modify the course of Alzheimer’s disease and that Alzheimer’s disease may modify the course of vascular dementia.38 Indeed, cerebrovascular disease lesions identified by structural magnetic resonance imaging are not consistently correlated with cognitive function in patients with ESRD.39–41 Furthermore, in several studies, CKD is associated with cognitive decline and dementia, independent of traditional vascular risk factors such as hypertension and diabetes, suggesting that factors associated with CKD and its treatment may be implicated in the pathogenesis of cognitive impairment.26–28 Nontraditional or ‘nephrogenic’ risk factors such as anemia and albuminuria are associated with cognitive impairment and dementia in several studies.11,42–44 The role of other nephrogenic factors such as retention of uremic solutes, inflammation, oxidative stress, and vascular calcification; treatment-related factors such as intradialytic hypotension and hyperviscosity; and genetic factors such as apolipopro-tein E or cystatin-c status has not been adequately studied in the ESRD population (Figure 3), but many of these factors have been associated with cognitive impairment among elderly without kidney disease.45–48

SCREENING FOR COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT

The optimal timing, frequency, and instruments for assessment of cognitive function in ESRD patients will depend on the clinical setting. For example, assessment of cognitive function during a hemodialysis session may be useful when trying to determine whether information communicated during rounds is understood, but in most other circumstances, assessment before or the day after dialysis would be preferred. Given the high prevalence of impairment among patients with CKD and the implications of a diagnosis of dementia on decision-making, screening for cognitive impairment should start before the onset of ESRD.

A large number of screening tests are available with a range of administration times and diagnostic accuracy.49–52 Table 2 lists the performance characteristics of several commonly used cognitive screening instruments that can be administered in ≤10 min. Scores on many screening instruments are influenced by age, educational level, and English fluency. Several tests also have ‘ceiling effects’, resulting in lower sensitivity for detecting dementia among highly educated patients and for detecting mild cognitive impairment. To our knowledge, no studies have validated the various cognitive screening instruments against a clinical diagnosis of dementia among patients with ESRD.

Table 2.

Performance characteristics of selected dementia screening instruments

| Instrument | Administration time (minutes) | Domains evaluated | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive screen cutpoint | Validation reference standard | Validated in CKD or ESRD | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kidney disease quality of life (KDQOL) cognitive function subscale | 1–2 | Self-report | 52 | 82 | 60 | Modified Mini-Mental State Exam <80 | Yes | |

| Six-item screener | 1–2 | Orientation Recall | 90–97 | 69–79 | ≥2 Errors | Clinical assessment for dementia | No | |

| Clock drawing task | 1–3 | Visuospatial Executive function | 85 | 85 | Various | Clinical assessment for dementia | No | Less cultural bias Evaluates executive function |

| Mini-cog | 3–4 | Visuospatial Executive function Recall | 76 | 89 | 2 | Neuropsychological battery | No | Clock drawing task plus uncued recall of three words |

| Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) | 7–10 | Orientation Recall Attention Visuospatial | 71–92 | 56–96 | 23–25 | Clinical assessment for dementia | No | Norms available Copyrighted Does not assess executive function well |

| St Louis University Mental Status Exam (SLUMS) | 7–10 | Orientation Recall Attention Visuospatial Executive function | 98–100 | 91–100 | 21.5 | Clinical assessment for dementia | No | Evaluates executive function |

| Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) | 10 | Orientation Recall Attention Visuospatial Verbal fluency Executive function | 100 | 87 | 25 | Neuropsychological battery | No | Evaluates executive function |

Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease, ESRD, end-stage renal disease.

Note: the sensitivity, specificity, and positive screen cutpoints listed above are for the general population (except for the KDQOL), as most of the above tests have not been validated in patients with ESRD.

The Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) is perhaps the best known and most studied cognitive test for dementia screening.52 A score of <24 (out of a maximum score of 30) has >80% sensitivity and specificity for dementia detection in several studies in the general population.49,53 Normative scores for age and educational level have been published.54 The MMSE also has several drawbacks, including copyright protection and the lack of executive function assessment. As deficits in executive function are a prominent feature of dementia from vascular causes and appear to be common among patients with ESRD,15,55 this may limit its sensitivity for dementia detection in the ESRD population. Newer instruments have been developed (for example, the Modified MMSE (3MS), St Louis University Mental Test (SLUMS), Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)) that address some of the limitations of the MMSE (Table 2).

Other screening tests that can be administered in ≤5 min, such as the Six-item Screener, the clock drawing task, and the Mini-cog (clock drawing plus uncued recall of three words) are reasonable options when time is limited. The Kidney Disease Quality of Life (KDQOL) cognitive function subscale has the advantage of using self-report and has been validated against the 3MS,18 but its sensitivity is lower than other brief screening instruments. One suggested screening strategy might be annual screening using a brief tool (for example Mini-cog), beginning before the onset of ESRD to establish the patient’s baseline level of functioning and to evaluate whether cognitive impairment might be complicating CKD management. A longer assessment tool (for example, MMSE, MoCA) might be used in highly educated patients or when greater specificity is needed and more time is available. Although these tests (with the exception of the KDQOL) generally have high sensitivity, specificity varies. Therefore, referral for neuropsychological testing should be considered for more extensive evaluation in complicated cases, such as determining the capacity for decision-making and establishing the diagnosis in patients with limited English proficiency or transplant candidates. These evaluations, typically lasting several hours, assess a range of cognitive domains more thoroughly than do screening instruments. Neuropsychological testing, when considered in conjunction with the history and physical examination, can confirm the diagnosis of dementia and provide clues to the underlying etiology, as different causes of dementia may feature deficits in one cognitive domain more prominently. In our opinion, neuropsychological testing is also valuable before initiation of pharmacotherapy to document the severity of dementia and follow the response to treatment.

EVALUATION OF COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT

History taking, ideally from the patient and caregiver, should focus on the onset, duration, and severity of cognitive and behavioral deficits, the presence of associated functional impairments (for example, difficulty in handling finances), and symptoms of depression or sleep disturbance. Caregivers often notice cognitive deficits before they are apparent to clinicians, and their observations or the availability of a pre-ESRD cognitive assessment is useful for helping to establish the course of impairment and for differentiating delirium from dementia. The examiner should look for focal neurological deficits suggestive of previous stroke and signs of Parkinsonism (for example, tremor, bradykinesia, or rigidity).

It is important to try to exclude delirium or depression as the sole cause of cognitive impairment before establishing a diagnosis of dementia, as these conditions are reversible, although, in practice, this may be difficult. Common causes of delirium include electrolyte disturbances (for example, hypoglycemia, hyponatremia, and hypercalcemia), medication side effects (opioids, benzodiazepines, antihistamines, antipsychotics, and anticholinergics), infections (catheter-related bacteremia or central nervous system infection), hypertensive encephalopathy, intoxications, alcohol withdrawal, and other organ failure states (cardiac or liver disease). Patients with symptoms of sleep disorders should be referred for confirmatory testing and treated, if indicated. Unnecessary or ineffective medications with central nervous system activity should be discontinued.15 Laboratory testing for B12 deficiency and hypothyroidism is recommended for all patients with suspected dementia. In ESRD patients, inadequate dialysis, severe anemia, and aluminum toxicity should also be ruled out. AIDS dementia complex should be considered in patients with human immunodeficiency virus risk factors. Testing for genetic markers of dementia risk (for example, apolipoprotein E variants) remains primarily in the research setting. Similarly, until the significance of neuroimaging abnormalities is more clearly defined, routine neuroimaging is probably not warranted but should be based on results of clinical findings.

MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES

Two classes of medications are now available for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease, cholinesterase inhibitors (tacrine, donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine) and N-methyl D-aspartate receptor antagonists (memantine).56–60 Rivastigmine, galantamine, and memantine may also have efficacy in patients with vascular dementia and/or dementia with mixed features (that is, features of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia), but do not have food and drug administration approval for this indication (Table 3).61 The clinical benefit of both classes of agents appears to be modest (roughly equivalent to a 4- to 6-month delay in cognitive decline), and the effect of treatment on long-term outcomes remains unclear. There is no published data on safety or efficacy of these agents in ESRD patients; thus, therapy decisions should be individualized.

Table 3.

Pharmacological therapy for dementia

| Drug class | Indication | Route of elimination | Usual starting dose | Dose modification in kidney disease? | Common side effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cholinesterase inhibitors | |||||

| Tacrine | Mild-to-moderate dementia from Alzheimer’s disease (used less commonly because of dosing frequency and need for lab monitoring) | Extensive hepatic metabolism | 10 mg every 6 h | No data, but probably not required | Dizziness, nausea, diarrhea, elevated transaminases, myalgia, neutropenia |

| Donepezil | Mild-to-severe dementia from Alzheimer’s disease | Partially excreted in unchanged form in urine and partially metabolized in liver | 5 mg at bedtime | Very limited data suggest that no dose modification is required | Dizziness, nausea, diarrhea, myalgia, insomnia |

| Rivastigmine | Mild-to-moderate dementia from Alzheimer’s disease | Extensive hepatic metabolism, metabolites excreted in urine | 1.5 mg twice a day | Very limited data suggest that no dose modification is required | Dizziness, nausea, diarrhea, anorexia |

| Galantamine | Mild-to-moderate dementia from Alzheimer’s disease | Partially excreted in unchanged form in urine and partially metabolized in liver | 4 mg twice a day | Maximum dose 16 mg daily in ‘moderate’ kidney disease. Use not recommended in ESRD | Dizziness, nausea, diarrhea, anorexia |

| N-methyl D-aspartate receptor antagonists | |||||

| Memantine | Moderate-to-severe dementia from Alzheimer’s disease | Partially excreted in unchanged form in urine and partially metabolized in liver | 5 mg daily | Maximum dose 5 mg twice a day for patients with creatinine clearance <30 ml/min or ESRD | Dizziness, hypertension, headache, constipation |

Behavioral symptoms associated with dementia, such as agitation or hallucinations are a prominent feature with more severe impairment and are especially distressing to patients and caregivers. These symptoms should be treated with a stepped approach, beginning with removal of precipitating factors (for example, pain and excessive noise), followed by psychosocial interventions, and pharmacological therapy as a last step, as many medications have not been shown to be efficacious or have significant adverse events.62 For example, several atypical antipsychotics have been associated with an increased risk of stroke and death among elderly patients with dementia.63 Caregivers should be encouraged to accompany patients to their treatments, if possible, as this may alleviate the patient’s anxiety and reduce the need for pharmacological therapy. Key aspects of dementia management are the assessment of patient safety and ability to perform self-care functions, comply with medical regimens, participate in medical decision-making, and plan for future care needs. A multi-disciplinary approach involving primary care, geriatrics, nursing, and social work is useful for addressing the complexity of medical and social issues in these patients.

The management of ESRD patients with mild cognitive impairment is uncertain. There is conflicting evidence regarding the role of vascular risk factor modification for prevention of dementia in the general population. For example, in a meta-analysis of hypertension trials, treatment of hypertension was associated with a 13% risk reduction for dementia.64 In contrast, a systematic review of hypertension trials that excluded participants with preexisting cerebrovascular disease suggested no benefit of hypertension treatment for preventing cognitive decline, but also no harm, as had been suggested in a few smaller studies.65 Clinical trials targeting glycemic and lipid control are in progress. Homocysteine lowering with B vitamin supplementation has failed to show benefit for reducing the risk of cognitive decline, both in the general population and in the CKD/ESRD population.13 Physical activity and cognitive activity have shown promise as effective interventions to slow cognitive decline in the general population.66 Given the other benefits of physical activity, in particular, and the relatively low risk of harm, these interventions may be attractive options for patients with ESRD and deserve further study.

Treatment of severe anemia with recombinant erythropoietin has been associated with improvement in neuropsychological test performance and electroencephalography measures in uncontrolled studies of patients with ESRD conducted in the early 1990s.67,68 The lack of control arms in these studies impairs the interpretation of these results, as learning effects can influence cognitive performance. It should be noted that pretreatment hematocrit in these studies was substantially lower than current practice (mean ~23%), and that achieved posttreatment hematocrit was consistent with current clinical practice guidelines (30–36%). One study suggested that normalization of hematocrit with erythropoietin was associated with further improvements in cognitive function,69 and others have suggested that erythropoietin may have neuroprotective effects independent of raising hemoglobin concentration. Large randomized trials of anemia correction using erythropoietin in CKD or ESRD did not evaluate cognitive function, and one suggested that active treatment was associated with an increased risk for stroke,70 which in turn is a major risk factor for dementia. Thus, there is currently insufficient evidence to justify changing current hemoglobin targets for the purposes of preventing dementia in patients with CKD or ESRD.

Similarly, although it is accepted that dialysis initiation reverses uremic encephalopathy, it is unknown whether even higher dialysis dose may improve cognitive function. In two observational studies of hemodialysis patients, higher Kt/V was associated with poorer cognitive function.11,15 Whether these findings were attributable to a deleterious effect of more intensive thrice-weekly dialysis or to confounding by indication and malnutrition is not clear. More frequent hemodialysis may be a potential management strategy in selected patients based on a small uncontrolled study of patients converting from conventional thrice-weekly hemodialysis to nocturnal hemodialysis;71 more definitive results may soon be available from randomized clinical trials. In short-term observational studies, kidney transplantation is associated with improvement in cognitive function;72 however, other studies suggest that significant residual impairment exists in some transplant recipients.73

ETHICAL AND HEALTH POLICY IMPLICATIONS

Guidelines from the Renal Physician’s Association suggest that it is appropriate to forego or withdraw dialysis from a patient with advanced dementia, especially if there are behavioral symptoms that impede the safe provision of dialysis.74 Surveys suggest that there is substantial practice variation surrounding this issue,75 highlighting the importance of prognostic discussions before the disease becomes advanced. These discussions are important for defining goals of care, and also for helping patients and caregivers understand what to expect, including anticipating the need for an escalation in care needs. In cases in which it is not clear whether a patient with severe cognitive impairment suffers from uremic encephalopathy or dementia, a time-limited trial of dialysis may be warranted. It is useful in these circumstances to be as explicit as possible about expectations beforehand, so that family members are not surprised about the indications for withdrawal of dialysis. For example, family members should be informed that it is not reasonable to forcibly dialyze a severely demented patient who is uncooperative with treatment. Hospice services are under-utilized among ESRD patients, yet may reduce unnecessary interventions and improve the quality of dying for ESRD patients with advanced dementia.

Although conducting research in individuals with cognitive impairment is crucial for improving care, it is also important to protect vulnerable participants. ESRD researchers must be familiar with methods to assess decision-making capacity and the use of surrogate decision makers to obtain informed consent.21 Finally, proposed ESRD quality improvement measures, pay for performance schemes, and new plans for reimbursement of ESRD services have generally failed to acknowledge the extent to which factors such as cognitive impairment might influence self-care and outcomes, or the additional time and cost required to provide optimal care for these patients.

SUMMARY

In summary, cognitive impairment including dementia is common among patients with ESRD and likely to contribute to adverse outcomes. Although available pharmacotherapy for dementia may have a limited role in patients with ESRD, other components of dementia care, such as management of behavioral symptoms, assessment of patient safety, and planning for future care needs, may reduce the burden of the disease and improve quality of life. Modification of vascular risk factors is a reasonable prevention strategy, although not specifically tested in patients with ESRD, whereas the role of interventions targeting proposed ESRD-associated risk factors such as anemia and dialysis dose awaits clarification from clinical trials. Given the aging of the ESRD population and the burdens of cognitive impairment, additional investigations in this area are desperately needed to inform clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kirsten Johansen and Glenn Chertow for their thoughtful review of earlier versions of the paper.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

MKT receives support from the National Institute of Aging (K23AG028952) and from a Norman S. Coplon grant from Satellite Research. She has previously received funding support from Amgen. KY is supported by R01DK069406 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. She serves on a data safety monitoring board for Pfizer and Medivation, and as a consultant to Novartis.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Task Force on DSM-IV. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. 4. xxvii. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. p. 886. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Querfurth HW, LaFerla FM. Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:329–344. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0909142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rozas VV, Port FK, Rutt WM. Progressive dialysis encephalopathy from dialysate aluminum. Arch Intern Med. 1978;138:1375–1377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manly JJ, Tang MX, Schupf N, et al. Frequency and course of mild cognitive impairment in a multiethnic community. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:494–506. doi: 10.1002/ana.21326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plassman BL, Langa KM, Fisher GG, et al. Prevalence of cognitive impairment without dementia in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:427–434. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-6-200803180-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teschan PE. Electroencephalographic and other neurophysiological abnormalities in uremia. Kidney Int Suppl. 1975;2:210–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arieff AI. Dialysis disequilibrium syndrome: current concepts on pathogenesis and prevention. Kidney Int. 1994;45:629–635. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams MA, Sklar AH, Burright RG, et al. Temporal effects of dialysis on cognitive functioning in patients with ESRD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:705–711. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murray AM, Pederson SL, Tupper DE, et al. Acute variation in cognitive function in hemodialysis patients: a cohort study with repeated measures. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;50:270–278. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kurella M, Chertow GM, Luan J, et al. Cognitive impairment in chronic kidney disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1863–1869. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murray AM, Tupper DE, Knopman DS, et al. Cognitive impairment in hemodialysis patients is common. Neurology. 2006;67:216–223. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000225182.15532.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sehgal AR, Grey SF, DeOreo PB, et al. Prevalence, recognition, and implications of mental impairment among hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;30:41–49. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(97)90563-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brady CB, Gaziano JM, Cxypoliski RA, et al. Homocysteine lowering and cognition in CKD: the Veterans Affairs homocysteine study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54:440–449. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook WL, Jassal SV. Functional dependencies among the elderly on hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2008;73:1289–1295. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurella Tamura M, Larive B, Unruh M, et al. Prevalence and correlates of cognitive impairment in the frequent hemodialysis network (FHN) trials. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;8:1429–1438. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01090210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leinau L, Murphy TE, Bradley E, et al. Relationship between conditions addressed by hemodialysis guidelines and non-ESRD-specific conditions affecting quality of life. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:572–578. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03370708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collins AJ, Kasiske B, Herzog C, et al. Excerpts from the United States Renal Data System 2006 Annual Data Report. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;49:A6–A7. S1–296. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurella M, Luan J, Yaffe K, et al. Validation of the Kidney Disease Quality of Life (KDQOL) cognitive function subscale. Kidney Int. 2004;66:2361–2367. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.66024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carrasco FR, Moreno A, Ridao N, et al. Kidney transplantation complications related to psychiatric or neurological disorders. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:2430–2432. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.06.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ettenhofer ML, Hinkin CH, Castellon SA, et al. Aging, neurocognition, and medication adherence in HIV infection. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17:281–290. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31819431bd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sugarman J, McCrory DC, Hubal RC. Getting meaningful informed consent from older adults: a structured literature review of empirical research. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:517–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb02477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen LM, Ruthazer R, Moss AH, et al. Predicting six-month mortality for patients who are on maintenance hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:72–79. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03860609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kurella M, Mapes DL, Port FK, et al. Correlates and outcomes of dementia among dialysis patients: the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:2543–2548. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kurella Tamura M, Covinsky KE, Chertow GM, et al. Functional status of elderly adults before and after initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1539–1547. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rakowski DA, Caillard S, Agodoa LY, et al. Dementia as a predictor of mortality in dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:1000–1005. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00470705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurella M, Chertow GM, Fried LF, et al. Chronic kidney disease and cognitive impairment in the elderly: the health, aging, and body composition study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:2127–2133. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005010005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seliger SL, Siscovick DS, Stehman-Breen CO, et al. Moderate renal impairment and risk of dementia among older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Cognition Study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:1904–1911. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000131529.60019.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khatri M, Nickolas T, Moon YP, et al. CKD associates with cognitive decline. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:2427–2432. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008101090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurella M, Yaffe K, Shlipak MG, et al. Chronic kidney disease and cognitive impairment in menopausal women. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45:66–76. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kurella Tamura M, Wadley V, Yaffe K, et al. Kidney function and cognitive impairment in US adults: the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52:227–234. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ikram MA, Vernooij MW, Hofman A, et al. Kidney function is related to cerebral small vessel disease. Stroke. 2008;39:55–61. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.493494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakatani T, Naganuma T, Uchida J, et al. Silent cerebral infarction in hemodialysis patients. Am J Nephrol. 2003;23:86–90. doi: 10.1159/000068034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seliger SL, Longstreth WT, Jr, Katz R, et al. Cystatin C and subclinical brain infarction. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3721–3727. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005010006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kobayashi S, Ikeda T, Moriya H, et al. Asymptomatic cerebral lacunae in patients with chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44:35–41. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Naganuma T, Uchida J, Tsuchida K, et al. Silent cerebral infarction predicts vascular events in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2005;67:2434–2439. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uzu T, Kida Y, Shirahashi N, et al. Cerebral microvascular disease predicts renal failure in type 2 diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:520–526. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009050558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fukunishi I, Kitaoka T, Shirai T, et al. Psychiatric disorders among patients undergoing hemodialysis therapy. Nephron. 2002;91:344–347. doi: 10.1159/000058418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fotuhi M, Hachinski V, Whitehouse PJ. Changing perspectives regarding late-life dementia. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5:649–658. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fazekas G, Fazekas F, Schmidt R, et al. Brain MRI findings and cognitive impairment in patients undergoing chronic hemodialysis treatment. J Neurol Sci. 1995;134:83–88. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(95)00226-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fazekas G, Fazekas F, Schmidt R, et al. Pattern of cerebral blood flow and cognition in patients undergoing chronic haemodialysis treatment. Nucl Med Commun. 1996;17:603–608. doi: 10.1097/00006231-199607000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hsieh TJ, Chang JM, Chuang HY, et al. End-stage renal disease: in vivo diffusion-tensor imaging of silent white matter damage. Radiology. 2009;252:518–525. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2523080484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barzilay JI, Fitzpatrick AL, Luchsinger J, et al. Albuminuria and dementia in the elderly: a community study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52:216–226. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.12.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vupputuri S, Shoham DA, Hogan SL, et al. Microalbuminuria, peripheral artery disease, and cognitive function. Kidney Int. 2008;73:341–346. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weiner DE, Bartolomei K, Scott T, et al. Albuminuria, cognitive functioning, and white matter hyperintensities in homebound elders. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;3:438–447. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin C, Wang ST, Wu CW, et al. The association of a cystatin C gene polymorphism with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Chin J Physiol. 2003;46:111–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sarnak MJ, Katz R, Fried LF, et al. Cystatin C and aging success. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:147–153. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yaffe K, Lindquist K, Shlipak MG, et al. Cystatin C as a marker of cognitive function in elders: findings from the health ABC study. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:798–802. doi: 10.1002/ana.21383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosano C, Naydeck B, Kuller LH, et al. Coronary artery calcium: associations with brain magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities and cognitive status. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:609–615. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Holsinger T, Deveau J, Boustani M, et al. Does this patient have dementia? JAMA. 2007;297:2391–2404. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.21.2391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tariq SH, Tumosa N, Chibnall JT, et al. Comparison of the Saint Louis University mental status examination and the mini-mental state examination for detecting dementia and mild neurocognitive disorder – a pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:900–910. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000221510.33817.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. ‘Mini-mental state’. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tangalos EG, Smith GE, Ivnik RJ, et al. The Mini-Mental State Examination in general medical practice: clinical utility and acceptance. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:829–837. doi: 10.4065/71.9.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Crum RM, Anthony JC, Bassett SS, et al. Population-based norms for the Mini-Mental State Examination by age and educational level. JAMA. 1993;269:2386–2391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pereira AA, Weiner DE, Scott T, et al. Subcortical cognitive impairment in dialysis patients. Hemodial Int. 2007;11:309–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2007.00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Memantine (package insert) St Louis, MO: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tacrine hydrochlorine (package insert) Atlanta, GA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Donepezil hydrochloride (package insert) Sellersville, PA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rivastigmine tartrate (package insert) East Hanover, NJ: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Galantamine (package insert) Sellersville, PA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Langa KM, Foster NL, Larson EB. Mixed dementia: emerging concepts and therapeutic implications. JAMA. 2004;292:2901–2908. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.23.2901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schneider LS, Tariot PN, Dagerman KS, et al. Effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic drugs in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1525–1538. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ballard C, Waite J. The effectiveness of atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of aggression and psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD003476. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003476.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Peters R, Beckett N, Forette F, et al. Incident dementia and blood pressure lowering in the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial cognitive function assessment (HYVET-COG): a double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:683–689. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70143-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McGuinness B, Todd S, Passmore P, et al. Blood pressure lowering in patients without prior cerebrovascular disease for prevention of cognitive impairment and dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(4):CD004034. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004034.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lautenschlager NT, Cox KL, Flicker L, et al. Effect of physical activity on cognitive function in older adults at risk for Alzheimer disease: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;300:1027–1037. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.9.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Grimm G, Stockenhuber F, Schneeweiss B, et al. Improvement of brain function in hemodialysis patients treated with erythropoietin. Kidney Int. 1990;38:480–486. doi: 10.1038/ki.1990.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Marsh JT, Brown WS, Wolcott D, et al. rHuEPO treatment improves brain and cognitive function of anemic dialysis patients. Kidney Int. 1991;39:155–163. doi: 10.1038/ki.1991.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pickett JL, Theberge DC, Brown WS, et al. Normalizing hematocrit in dialysis patients improves brain function. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999;33:1122–1130. doi: 10.1016/S0272-6386(99)70150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pfeffer MA, Burdmann EA, Chen CY, et al. A trial of darbepoetin alfa in type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2019–2032. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jassal SV, Devins GM, Chan CT, et al. Improvements in cognition in patients converting from thrice weekly hemodialysis to nocturnal hemodialysis: a longitudinal pilot study. Kidney Int. 2006;70:956–962. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Griva K, Thompson D, Jayasena D, et al. Cognitive functioning pre- to post-kidney transplantation –a prospective study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:3275–3282. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gelb S, Shapiro RJ, Hill A, et al. Cognitive outcome following kidney transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:1032–1038. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Moss AH. Shared decision-making in dialysis: the new RPA/ASN guideline on appropriate initiation and withdrawal of treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37:1081–1091. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(05)80027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Moss AH, Stocking CB, Sachs GA, et al. Variation in the attitudes of dialysis unit medical directors toward decisions to withhold and withdraw dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1993;4:229–234. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V42229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]