Abstract

Evidence points to the endogenous opioid system, and the mu-opioid receptor (MOR) in particular, in mediating the rewarding effects of drugs of abuse, including nicotine. A single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the human MOR gene (OPRM1 A118G) has been shown to alter receptor protein level in preclinical models and smoking behavior in humans. To clarify the underlying mechanisms for these associations, we conducted an in vivo investigation of the effects of OPRM1 A118G genotype on MOR binding potential (BPND or receptor availability). Twenty-two smokers prescreened for genotype (12 A/A, 10 */G) completed two [11C]carfentanil positron emission tomography (PET) imaging sessions following overnight abstinence and exposure to a nicotine-containing cigarette and a denicotinized cigarette. Independent of session, smokers homozygous for the wild-type OPRM1 A allele exhibited significantly higher levels of MOR BPND than smokers carrying the G allele in bilateral amygdala, left thalamus, and left anterior cingulate cortex. Among G allele carriers, the extent of subjective reward difference (denicotinized versus nicotine cigarette) was associated significantly with MOR BPND difference in right amygdala, caudate, anterior cingulate cortex, and thalamus. Future translational investigations can elucidate the role of MORs in nicotine addiction, which may lead to development of novel therapeutics.

Keywords: genetics, neuroimaging, tobacco

With 1 billion tobacco users worldwide, nicotine dependence has a major impact on global health. Advances in medication development for nicotine dependence require an improved understanding of the neurobiology of this complex, relapsing brain disorder (1). Although multiple neurobiological mechanisms have been implicated, a growing body of evidence points to the endogenous opioid system, and the mu-opioid receptor (MOR) in particular, in mediating the reinforcing effects of drugs of abuse, including nicotine (2–5). Nicotine up-regulates MOR mRNA and protein expression in brain regions important in drug reward in rodents (4, 6) and stimulates endogenous opioid release (7, 8), resulting in MOR activation and dopamine release (9).

Genetic variation in MORs can modulate the endogenous opioid system, thereby altering behavior. A common single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the mu-opioid receptor gene (OPRM1 A118G) results in an amino acid exchange at a putative glycosylation site in the extracellular terminus of the MOR (10). This OPRM1 SNP has been associated with a variety of drug dependence phenotypes in rodent and human studies (11), including nicotine reward, nicotine withdrawal severity, and smoking relapse (12–14).

Despite substantial attention to the OPRM1 A118G in drug addiction research, the precise function of this SNP has yet to be clarified. Although the minor (G) allele was originally thought to be a “gain-of-function” variant, on the basis of increased affinity of MOR agonists (15), other data suggest that the G allele is associated with reduced mRNA and protein expression (16, 17). Further, knock-in mice homozygous for the equivalent (112G) allele exhibit reduced MOR mRNA and protein levels in multiple brain regions, providing additional support for a “loss-of-function” phenotype (18).

To translate these preclinical data to humans, we conducted an in vivo investigation of the effects of OPRM1 A118G genotype on MOR binding potential (BPND or receptor availability). Twenty-two smokers prescreened for OPRM1 A118G genotype (12 A/A, 10 */G) completed [11C]carfentanil positron emission tomography (PET) imaging during two separate sessions, both occurring after overnight (14 h) abstinence (i) after smoking a nicotine-containing cigarette and (ii) after smoking a denicotinized (placebo) cigarette. Twenty nonsmoking controls (10 A/A, 10*/G) balanced for age and sex completed a single PET session. On the basis of the finding of reduced protein levels of MOR in knock-in mice that carry the G allele (18), we predicted that OPRM1 G allele carriers would have reduced MOR BPND compared with those homozygous for the A allele. Furthermore, we hypothesized that the extent of displacement of the radioligand (i.e., changes in MOR BPND across the two sessions) would be reduced in smokers with the G allele (14). Regions with high MOR density (19–21), which are important in the mesolimbic reward circuits in addiction (22), were selected as regions of interest (ROIs): anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), amygdala (AMY), caudate (CAU), ventral striatum/nucleus accumbens (VST), and thalamus (THA).

Results

The BPND in the regions of interest was calculated using the multilinear graphical analysis method evaluated by the second version of the multilinear reference tissue model (MRTM2) (23). The occipital cortex (OCC) was identified as a region of interest for use as the reference region in MRTM2 modeling (24). All regression models for MOR BPND included predictors of interest (e.g., genotype, session) and controlled for age, sex, and smoking rate (for smokers only).

Smokers Carrying the OPRM1 G Allele Exhibit Reduced MOR BPND Compared with Those Homozygous for the A (Wild-Type) Allele.

Smokers in the */G genotype group exhibited reduced MOR BPND in several of the ROIs examined. In the cross-session models, MOR BPND was significantly lower in G allele carriers in bilateral AMY [left: β = −0.32 (−0.54 to −0.10), P = 0.004; right: β = −0.25 (−0.46 to −0.05), P = 0.017], left ACC [β = −0.27 (−0.48 to −0.06), P = 0.01], and left THA [β = −0.23 (−0.37 to −0.10), P = 0.001]. Right THA did not survive correction (P = 0.04). Cross-session models for CAU and VST were not significant.

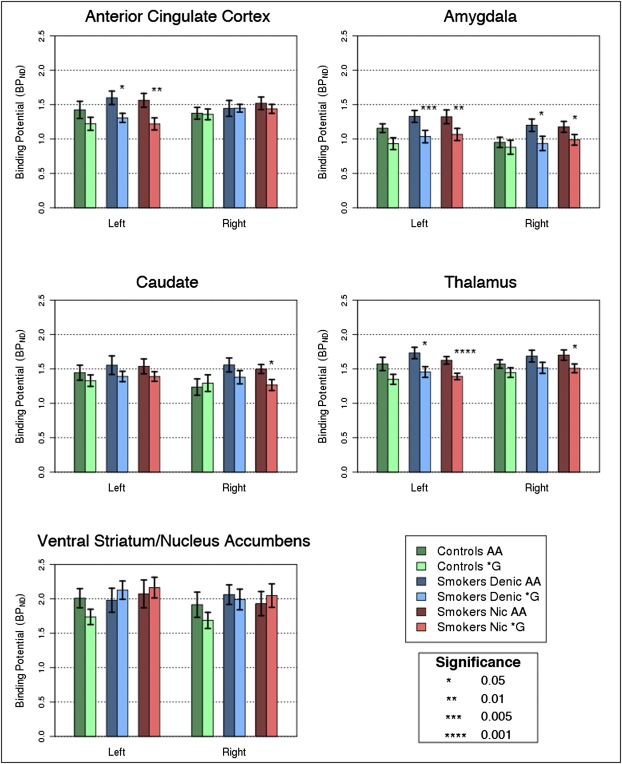

As shown in Fig. 1, in the nicotine cigarette session, G allele carriers exhibited reduced MOR BPND in the left AMY [β = −0.31 (−0.55 to −0.07), P = 0.01], left ACC [β = −0.30 (−0.53 to −0.06), P = 0.01], and left THA [β = −0.23 (−0.36 to −0.10), P = 0.0004]. Right AMY (P = 0.03), right CAU (P = 0.02), and right THA (P = 0.02) did not survive correction. In the denicotinized cigarette session, significant associations were identified in the left AMY (β = −0.34 (−0.57 to −0.10), P = 0.005) and left ACC (β = −0.24 (−0.44 to −0.04), P = 0.018). Right AMY (P = 0.03) and left THA (P = 0.03) did not survive correction. VST models were not significant in either session. The observed genotype associations did not differ by session (P values for genotype × session effects > 0.50). In the nonsmoking controls, genotype associations were not significant (P values > 0.10).

Fig. 1.

Quantification of MOR BPND across the five ROIs and each hemisphere, comparing the A/A versus */G OPRM1 groups among nonsmokers, smokers during the denicotinized cigarette session, and smokers during the nicotine cigarette session. ACC, anterior cingulate cortex; AMY, amygdala; CAU, caudate; THA, thalamus; and VST, ventral striatum/nucleus accumbens.

Changes in MOR BPND Correlate with Changes in Smoking Reward in G Allele Carriers.

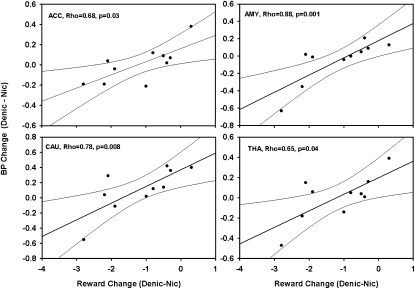

With respect to subjective ratings, the nicotine cigarette was rated as significantly more rewarding than the denicotinized cigarette [3.63 (SD = 1.00) versus 2.34 (SD = 0.70), respectively; T = −4.55, P = 0.0002]; subjective reward did not differ by genotype. As shown in Fig. 2, among G allele carriers, the magnitude of change in MOR BPND from the denicotinized cigarette to the nicotine session was significantly correlated (Spearman's correlation) with change in the self-reported rewarding effects of these cigarettes in the right AMY (r = 0.88, P = 0.001), right CAU (r = 0.78, P = 0.008), right ACC (r = 0.68, P = 0.03), and right THA (r = 0.65, P = 0.04). There were correlations that approached significance in the left CAU (r = 0.58, P = 0.08), left THA (r = 0.58, P = 0.08), and left ACC (r = 0.56, P = 0.09). Significant correlations were not observed in the AA group (all P values > 0.10).

Fig. 2.

Spearman's correlations of magnitude of change in MOR BPND from the denicotinized cigarette to the nicotine cigarette session with change in the self-reported rewarding effects of these cigarettes.

Comparisons of BPND in smokers (across sessions) versus nonsmokers revealed a difference only in bilateral AMY [β = −0.17 (−0.33 to −0.02), P = 0.03], but this effect did not survive correction. Session-specific comparisons of BPND in smokers versus controls were not significant (all P values > 0.10).

Discussion

This translational study provides unique evidence linking human genetic variation in the MOR to in vivo receptor binding availability. Consistent with preclinical data (18), smokers homozygous for the wild-type OPRM1 A allele exhibited higher levels of MOR BPND in the bilateral amygdala, left thalamus, and left anterior cingulate cortex compared with those with the G allele. Among G allele carriers, the extent of subjective reward difference (denicotinized versus nicotine cigarette) was associated significantly with MOR BPND difference in right amygdala, caudate, anterior cingulate cortex, and thalamus. These regions have high MOR density (19–21) and are important in the mesolimbic reward circuits in addiction (22). Thus, the current findings may partly explain the reduced nicotine reward, withdrawal, and relapse risk associated with the A118G polymorphism (12–14, 25).

The observation of a relative reduction in MOR BPND in multiple regions among OPRM1 G allele carriers is consistent with observations from a knock-in mouse model, in which mice possess the A112G polymorphism that corresponds to the same amino acid change in humans (18). At the molecular level, the 112G mice exhibit reduced mRNA expression and MOR protein, as well as decreased [3H]DAMGO binding in thalamus (18). Data from the mouse and the current human study are also consistent with evidence for OPRM1 G allele-specific decreases in MOR mRNA and protein observed in postmortem human brain (17). The present study provides in vivo evidence for this association in human smokers.

Whereas the genotype associations in this study are consistent with preclinical data, the specific mechanisms underlying the association of the OPRM1 G allele with reduced MOR BPND are not yet clear. The possibility of a constitutive effect of the OPRM1 genotype received limited support in our study, on the basis of the lack of significant genotype associations with MOR BPND in the nonsmokers; however, the knock-in mouse data identify genotype differences in nicotine-naïve animals (18). An alternate hypothesis is that long-term chronic exposure to nicotine produces greater up-regulation in the A/A group or down-regulation in the */G group, a hypothesis that could be tested in the A112 knock-in mice. It is also plausible that the MOR BPND differences are secondary to variation in endogenous opioid tone in the two genotype groups. A postmortem brain investigation of heroin addicts linked the G allele with disruptions in the endogenous opioid neuropeptide system (26). Also supporting this mechanism, G allele carriers exhibit elevated cortisol responses to MOR blockade (27).

Our finding that subjective nicotine reward in G allele carriers is associated with MOR availability in the amygdala, thalamus, anterior cingulate cortex, and caudate supports the endogenous opioid stimulation mechanism. MORs located in the thalamus (28) and amygdala (9) decrease excitatory glutamate inputs to the striatum, which influence striatal dopaminergic firing and subsequently nicotine reward. The caudate also has a high density of MORs, which are colocalized on the inhibitory GABA-ergic medium-spiny neurons that project from caudate-putamen to the striatum (29). The projection from the caudate-putamen also contributes to reward-related learning (30).

Whereas the explanation for observing MOR BPND associations with reward in G allele carriers but not in the A/A group is not entirely clear, it is plausible that this observation reflects genotype differences in sensitivity associated with molecular adaptations resulting from lower MOR availability in the */G group. Indeed, evidence cited above (26, 27) suggests that compensatory alterations in endogenous opioid tone are present in this group. Altered levels of G protein-coupled signaling molecules have also been observed in Neuro 2A cells transfected with the 118G hOPRM1 (31). Additional clinical evidence suggests that carriers of the OPRM1 118G polymorphism exhibit increased sensitivity to pain (32), as well as increased sensitivity to psychosocial stress at both the subjective and neural levels (33). Interestingly, during the stress challenge, increased neural activity in the G allele carriers was observed in the anterior cingulate cortex (33), a region significant for MOR BPND and reward differences in the current study. Thus, as previously suggested (18), it may be an oversimplification to consider the A118G SNP to be either a gain or loss of function SNP, and genotype effects may vary depending on the specific pharmacological challenge.

It should be noted that the absence of differences in MOR BPND following denicotinzed and nicotine cigarettes (versus controls) contrasts with the only study of MOR BPND in smokers, which was a small pilot feasibility study (34). The discrepant results are likely attributable to differences in the study populations and designs. For example, the prior study included 6 smokers (all male) compared with 22 smokers of both genders and matched OPRM1 genotypes (oversampling the */G group) in the current study. Further, the current study was designed to eliminate carryover effects of smoking by scanning smokers on two separate occasions. It will be important in future studies to include sufficient numbers of males and females, as the behavioral effects of this polymorphism may be sex specific (14, 18, 35), and female sex and estradiol alter MOR binding availability (36, 37).

This study has several limitations. BPND values for nonsmokers in our study are lower than findings reported in some previously published studies (38, 39); however, these values were comparable to other studies (40, 41). These differences in MOR BPND may be attributable to the oversampling in our study of carriers of the OPRM1 G allele who have lower BPND (comprising ∼50% of our sample versus 15–20% in the general population). It should also be mentioned that we did not assess plasma nicotine levels nor did we use a smoking topography device to measure puff volumes. Although there may be individual differences in puff volume, this is mitigated by using a standardized puffing procedure (42) and demonstrating significant differences in exhaled CO and subjective reward between sessions. Further, prior studies demonstrated large differences (>0.5 mg) in plasma nicotine levels between the 0.6 mg and 0.05 mg Quest cigarettes, which persist up to 5 h after smoking (43). Lastly, the number of female smokers was insufficient to test for sex heterogeneity in genotype effects or MOR BPND observed in prior studies (14, 37). However, sex was considered as a covariate in all models and did not predict MOR BPND. As is the case with any PET receptor binding potential study, it is not possible to disentangle differences in receptor numbers from receptor binding affinity or endogenous opioid tone, a question best answered in preclinical models.

This PET imaging study demonstrates that preclinical evidence for genetic differences in MOR protein translates to in vivo observations of decreased MOR binding availability in human smokers. This is a critical first step toward elucidating the mechanistic basis of previously observed genetic associations with smoking behavior and other drug abuse phenotypes, which have high comorbidity with smoking. This work lays the foundation for future studies to evaluate whether MOR BPND predicts smoking relapse in treatment seekers. PET imaging of MORs at pretreatment could potentially identify relapse-prone smokers, thereby optimizing treatment selection and improving outcomes for this major medical and public health problem.

Materials and Methods

Participants.

The study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board, the Food and Drug Administration, and the Environmental Health and Radiation Safety Committee. All participants provided written informed consent. Smokers (n = 22) and nonsmokers (n = 20) were recruited through mass media. Smokers were required to report consumption of ≥10 cigarettes per day for at least the past 6 mo and provide a baseline breath carbon monoxide (CO) reading >10 ppm. Nonsmokers were required to report smoking <100 cigarettes/lifetime, no cigarettes in the past year, and provide a CO reading of <5 ppm (CO readings allowed for effects of environmental CO). Individuals with a history of or current neurological or DSM-IV Axis I psychiatric or substance disorders (except nicotine dependence), and those taking psychotropic medications (e.g., antidepressants, antipsychotics, anxiolytics, and mood stabilizers) or opioid analgesics were excluded. Due to the influence of female sex hormones on MOR levels (37), postmenopausal women were excluded from the study. Only individuals of European ancestry were included due to ethnic differences in allele frequencies (10).

Procedures.

Following preliminary eligibility assessment, participants were assessed for OPRM1 A118G (rs1799971) genotype using Taqman SNP genotyping assays (Applied Biosystems). Of 51 smokers who were eligible at initial screening, 26 smokers were eligible after OPRM1 genotype, and 22 smokers completed both their PET scans (12 A/A, 10 */G); 3 smokers were ineligible at their PET scan 1, and 1 participant withdrew before their first PET scan. Of 59 nonsmokers who were eligible at the medical screen, only 21 were eligible on the basis of OPRM1 genotype and all participants completed their PET scan. One nonsmoker was excluded due to lower than threshold (<3 mCi) radio activity injected during their PET scan, leaving a final sample of 20 nonsmokers (10 A/A, 10 */G).

The final sample of 16 male and six female smokers included 12 A/A, 9 A/G, and 1 G/G OPRM1 A118G genotype (A/G and G/G genotype groups combined, denoted as */G). These smokers reported a mean age of 31.3 y (SD = 10.7), smoking rate of 17.6 cigarettes/day (SD = 6.3), and Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence score of 4.68 (SD = 2.01). The final sample of 13 male and seven female nonsmokers included 10 A/A and 10 */G genotypes, with a mean age of 30.9 y (SD = 12.3). There were no significant differences in demographics between A/A and */G groups, between smokers and nonsmokers, or between genotype groups in smoking history (smokers only) (all P values >0.10).

Following 14 h of overnight abstinence (verified by expired CO < 10 ppm), smokers participated in two 60-min [11C]carfentanil PET scans on two separate occasions. Fifteen minutes before each scan, participants smoked a Quest research cigarette (Vector Tobacco). The nicotine cigarette (0.6 mg nicotine) was smoked before scan 1 and the placebo cigarette (denicotinized; 0.05 mg nicotine) was smoked before scan 2. Participants and data analysts were blind to the cigarette type. To standardize exposure, the cigarettes were smoked through a controlled puffing procedure (participants were allowed to take a total of six puffs after lighting the cigarette, each puff was separated by 30 s) (42). The breath expired CO level change from pre- to postcigarette was 4.95 (SD = 1.73) after the nicotine cigarette and 3.27 (SD = 1.42) after the denicotinized cigarette (T = −4.71, P = 1 × 10−4). After smoking, participants completed a questionnaire to evaluate the smoking reward they experienced from the cigarette (44). Female participants were scanned during their early follicular phase (2–9 d after menses) to minimize the effects of rising levels of estrogen on the endogenous opioid system (45). The time interval between the two scans was 1–4 wk (as female participants were scanned during their early follicular phase).

Image Acquisition and Reconstruction.

Scans were acquired on a GSO-based brain PET scanner, which operates without septa to increase the sensitivity of the instrument (46). Six sequential 10-min long scans were acquired starting immediately after slow bolus injection (over 10 min) of 3–15 mCi [11C]carfentanil, so as not to exceed 0.03 μg/kg. The dose of [11C]carfentanil administered was based on published PET studies (36, 47, 48). The range of specific activity for [11C]carfentanil was 1,500–3,000 mCi/μmol. Upon completion of the emission scan, a transmission scan was acquired using a 137Cs point source and used to perform a segmented attenuation correction. The PET data were reconstructed using an iterative 3D-RAMLA algorithm with scatter correction performed using a fully 3D single scatter simulation algorithm (49). The resulting six images consisted of 128 slices of 2-mm slice thickness (2 × 2 mm2 pixels) and an image matrix size of 128 × 128 pixels).

Single Subject Image Preprocessing.

The raw PET data were converted to Neuroimaging Informatics Technology Initiative format and preprocessed using SPM8 (Wellcome Trust Center for Neuroimaging, London, United Kingdom) implemented in Matlab 7.10. The mean image calculated from each subject's six images (0–60 min) was manually reoriented to set the origin to the anterior commissure (AC) with slice position aligned to the AC–posterior commissure (PC) line. The reorientation translation parameters were then applied to all six images. The mean image was spatially normalized to the T1 weighted template provided by the Montreal Neurological Institute by means of a least-squares approach and 12-parameter spatial transformation followed by estimating nonlinear deformations. Default parameters as defined in SPM8 were used except the bounding box, which was matched to the T1 template. A brain mask in each subject's native space was derived by applying the inverse of the deformation fields to the T1 template. To transform the T1 template in native subject space, deformation fields were computed from the individual normalization parameters using the “Deformations” toolbox in SPM8. Nonbrain areas were removed using this brain mask from all six images.

Regional Time Activity Curve (TAC) Computation.

Left and right hemisphere masks were defined for the ACC, AMY, CAU, VST, and THA using the Harvard–Oxford probabilistic map (maximal probability threshold: 25%) distributed with FSL software (50). The ventral striatum ROI was composed of the nucleus accumbens and the ventral part of putamen and caudate nucleus using methods described above. The spatially transformed ROIs were then applied to the subject's six images and regional TACs were extracted.

Quantification of MOR Binding (BPND).

MOR binding was estimated using MRTM2 (23) with a fixed value for the tissue to plasma efflux rate constant in the reference region (k2′). The distribution volume ratio (DVR) is calculated from the ratio of the regression coefficients (23) and the binding potential is given by BPND = DVR − 1. A k2′ value of 0.1237 min−1 was assigned on the basis of a previous [11C]carfentanil study (51). The MRTM2 BPND values calculated for each ROI were exported for further statistical analysis using Stata software.

Statistical Analysis.

Because the outcome of interest (MOR BPND by ROI) is continuous, and observations sometimes included repeated measures (across sessions), we analyzed the data using a multiple linear regression and used the cluster-corrected robust covariance matrix to correct SEs (52). We tested the effect of the OPRM1 genotype (A/A vs. */G) in separate models of MOR BPND for smokers, adjusted for age, sex, session, and cigarettes per day and for nonsmokers, not adjusted for session. Results reported are from models testing both hemispheres simultaneously using “seemingly unrelated estimation” used to test similarity across hemispheres (53). Additionally, in the smoker models, we used the Wald χ2 to test for genotype × session interaction. Alpha was adjusted on the basis of 10 ROIs with an average correlation of 0.55, resulting in an adjusted P value of 0.018 (54). On the basis of correlated observations for BPND in the different ROIs, 22 smokers gave us 80% power to detect a session effect size of 0.664 (correlation adjusted to 0.39) for a one-sample test and a genotype (between) effect size of 1.26. This compares favorably to prior MOR binding studies with similar manipulations (24, 55). Secondary analysis examined the Spearman's correlation of MOR BPND (by ROI) with the continuous smoking reward measure. Significance was obtained using linear regression, with SEs corrected for cluster correlation (tested at P = 0.05).

Acknowledgments

We thank the following individuals for their contributions to the study: Dr. Richard Freifelder, Dr. Joel Karp, Dr. Alexander Schmitz, and Rahul Poria for [11C]carfentanil synthesis; Dr. Daniel Pryma and Dr. Rodolfo Perini for serving as PET center injectors; and Dr. Janet Reddin and PET center technologists for PET acquisition and preprocessing at the PET center. This research was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse Grants R21-DA027066 (to C.L. and J.A.B.) and U01-DA020830 (to C.L.), National Cancer Institute Grant P50-CA143187 (to C.L. and J.A.B.), and a grant from the Pennsylvania Department of Health.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

References

- 1.Lerman C, et al. Translational research in medication development for nicotine dependence. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:746–762. doi: 10.1038/nrd2361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berrendero F, Kieffer BL, Maldonado R. Attenuation of nicotine-induced antinociception, rewarding effects, and dependence in mu-opioid receptor knock-out mice. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10935–10940. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-24-10935.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trigo JM, Martin-García E, Berrendero F, Robledo P, Maldonado R. The endogenous opioid system: A common substrate in drug addiction. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;108:183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walters CL, Cleck JN, Kuo YC, Blendy JA. Mu-opioid receptor and CREB activation are required for nicotine reward. Neuron. 2005;46:933–943. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xue Y, Domino EF. Tobacco/nicotine and endogenous brain opioids. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32:1131–1138. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wewers ME, Dhatt RK, Snively TA, Tejwani GA. The effect of chronic administration of nicotine on antinociception, opioid receptor binding and met-enkelphalin levels in rats. Brain Res. 1999;822:107–113. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01095-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyadjieva NI, Sarkar DK. The secretory response of hypothalamic beta-endorphin neurons to acute and chronic nicotine treatments and following nicotine withdrawal. Life Sci. 1997;61:PL59–PL66. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)00444-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davenport KE, Houdi AA, Van Loon GR. Nicotine protects against mu-opioid receptor antagonism by beta-funaltrexamine: Evidence for nicotine-induced release of endogenous opioids in brain. Neurosci Lett. 1990;113:40–46. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90491-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nestler EJ. Is there a common molecular pathway for addiction? Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1445–1449. doi: 10.1038/nn1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gelernter J, Kranzler H, Cubells J. Genetics of two mu opioid receptor gene (OPRM1) exon I polymorphisms: Population studies, and allele frequencies in alcohol- and drug-dependent subjects. Mol Psychiatry. 1999;4:476–483. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mague SD, Blendy JA. OPRM1 SNP (A118G): involvement in disease development, treatment response, and animal models. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;108:172–182. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lerman C, et al. The functional mu opioid receptor (OPRM1) Asn40Asp variant predicts short-term response to nicotine replacement therapy in a clinical trial. Pharmacogenomics J. 2004;4:184–192. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perkins KA, et al. Dopamine and opioid gene variants are associated with increased smoking reward and reinforcement owing to negative mood. Behav Pharmacol. 2008;19:641–649. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32830c367c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ray R, et al. Association of OPRM1 A118G variant with the relative reinforcing value of nicotine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;188:355–363. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0504-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bond C, et al. Single-nucleotide polymorphism in the human mu opioid receptor gene alters beta-endorphin binding and activity: Possible implications for opiate addiction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9608–9613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beyer A, Koch T, Schröder H, Schulz S, Höllt V. Effect of the A118G polymorphism on binding affinity, potency and agonist-mediated endocytosis, desensitization, and resensitization of the human mu-opioid receptor. J Neurochem. 2004;89:553–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Y, Wang D, Johnson AD, Papp AC, Sadée W. Allelic expression imbalance of human mu opioid receptor (OPRM1) caused by variant A118G. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:32618–32624. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504942200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mague SD, et al. Mouse model of OPRM1 (A118G) polymorphism has sex-specific effects on drug-mediated behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:10847–10852. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901800106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arvidsson U, et al. Distribution and targeting of a mu-opioid receptor (MOR1) in brain and spinal cord. J Neurosci. 1995;15:3328–3341. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-03328.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mansour A, Khachaturian H, Lewis ME, Akil H, Watson SJ. Anatomy of CNS opioid receptors. Trends Neurosci. 1988;11:308–314. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(88)90093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfeiffer A, Pasi A, Mehraein P, Herz A. Opiate receptor binding sites in human brain. Brain Res. 1982;248:87–96. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)91150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:217–238. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ichise M, et al. Linearized reference tissue parametric imaging methods: Application to [11C]DASB positron emission tomography studies of the serotonin transporter in human brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:1096–1112. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000085441.37552.CA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zubieta JK, et al. COMT val158met genotype affects mu-opioid neurotransmitter responses to a pain stressor. Science. 2003;299:1240–1243. doi: 10.1126/science.1078546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hardin J, et al. Nicotine withdrawal sensitivity, linkage to chr6q26, and association of OPRM1 SNPs in the SMOking in FAMilies (SMOFAM) sample. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:3399–3406. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drakenberg K, et al. Mu opioid receptor A118G polymorphism in association with striatal opioid neuropeptide gene expression in heroin abusers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:7883–7888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600871103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chong RY, et al. The mu-opioid receptor polymorphism A118G predicts cortisol responses to naloxone and stress. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:204–211. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lambe EK, Picciotto MR, Aghajanian GK. Nicotine induces glutamate release from thalamocortical terminals in prefrontal cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:216–225. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang H, Moriwaki A, Wang JB, Uhl GR, Pickel VM. Ultrastructural immunocytochemical localization of mu opioid receptors in dendritic targets of dopaminergic terminals in the rat caudate-putamen. Neuroscience. 1997;81:751–771. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00253-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wickens JR, Budd CS, Hyland BI, Arbuthnott GW. Striatal contributions to reward and decision making: Making sense of regional variations in a reiterated processing matrix. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1104:192–212. doi: 10.1196/annals.1390.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deb I, Chakraborty J, Gangopadhyay PK, Choudhury SR, Das S. Single-nucleotide polymorphism (A118G) in exon 1 of OPRM1 gene causes alteration in downstream signaling by mu-opioid receptor and may contribute to the genetic risk for addiction. J Neurochem. 2010;112:486–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rainville P. Brain mechanisms of pain affect and pain modulation. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2002;12:195–204. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(02)00313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Way BM, Taylor SE, Eisenberger NI. Variation in the mu-opioid receptor gene (OPRM1) is associated with dispositional and neural sensitivity to social rejection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:15079–15084. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812612106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scott DJ, et al. Smoking modulation of mu-opioid and dopamine D2 receptor-mediated neurotransmission in humans. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:450–457. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Munafò MR, Elliot KM, Murphy MF, Walton RT, Johnstone EC. Association of the mu-opioid receptor gene with smoking cessation. Pharmacogenomics J. 2007;7:353–361. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith YR, et al. Pronociceptive and antinociceptive effects of estradiol through endogenous opioid neurotransmission in women. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5777–5785. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5223-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zubieta JK, Dannals RF, Frost JJ. Gender and age influences on human brain mu-opioid receptor binding measured by PET. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:842–848. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Endres CJ, Bencherif B, Hilton J, Madar I, Frost JJ. Quantification of brain mu-opioid receptors with [11C]carfentanil: Reference-tissue methods. Nucl Med Biol. 2003;30:177–186. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(02)00411-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heinz A, et al. Correlation of stable elevations in striatal mu-opioid receptor availability in detoxified alcoholic patients with alcohol craving: A positron emission tomography study using carbon 11-labeled carfentanil. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:57–64. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bencherif B, et al. Mu-opioid receptor binding measured by [11C]carfentanil positron emission tomography is related to craving and mood in alcohol dependence. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:255–262. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Greenwald MK, et al. Effects of buprenorphine maintenance dose on mu-opioid receptor availability, plasma concentrations, and antagonist blockade in heroin-dependent volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:2000–2009. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strasser AA, Ashare RL, Kozlowski LT, Pickworth WB. The effect of filter vent blocking and smoking topography on carbon monoxide levels in smokers. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;82:320–329. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brody AL, et al. Brain nicotinic acetylcholine receptor occupancy: Effect of smoking a denicotinized cigarette. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;12:305–316. doi: 10.1017/S146114570800922X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cappelleri JC, et al. Confirmatory factor analyses and reliability of the modified cigarette evaluation questionnaire. Addict Behav. 2007;32:912–923. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mills RH, Sohn RK, Micevych PE. Estrogen-induced mu-opioid receptor internalization in the medial preoptic nucleus is mediated via neuropeptide Y-Y1 receptor activation in the arcuate nucleus of female rats. J Neurosci. 2004;24:947–955. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1366-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karp JS, et al. Performance of a brain PET camera based on anger-logic gadolinium oxyorthosilicate detectors. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:1340–1349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Greenwald M, et al. Buprenorphine duration of action: Mu-opioid receptor availability and pharmacokinetic and behavioral indices. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zubieta JK, et al. Placebo effects mediated by endogenous opioid activity on mu-opioid receptors. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7754–7762. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0439-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Accorsi R, Adam LE, Werner ME, Karp JS. Optimization of a fully 3D single scatter simulation algorithm for 3D PET. Phys Med Biol. 2004;49:2577–2598. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/49/12/008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith SM, et al. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage. 2004;23(Suppl 1):S208–S219. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hirvonen J, et al. Measurement of central mu-opioid receptor binding in vivo with PET and [11C]carfentanil: A test-retest study in healthy subjects. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36:275–286. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-0935-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Williams RL. A note on robust variance estimation for cluster-correlated data. Biometrics. 2000;56:645–646. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clogg CC, Petkova E, Haritou A. Statistical methods for comparing regression coefficients between models. Am J Sociol. 1995;100:1261–1293. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sankoh AJ, Huque MF, Dubey SD. Some comments on frequently used multiple endpoint adjustment methods in clinical trials. Stat Med. 1997;16:2529–2542. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19971130)16:22<2529::aid-sim692>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Scott DJ, Stohler CS, Koeppe RA, Zubieta JK. Time-course of change in [11C]carfentanil and [11C]raclopride binding potential after a nonpharmacological challenge. Synapse. 2007;61:707–714. doi: 10.1002/syn.20404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]