Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the effects of patient-practitioner interaction on the severity and duration of the common cold.

Methods

We conducted a randomized controlled trial of 719 patients with new cold onset. Participants were randomized to three groups: no patient-practitioner interaction, “standard” interaction or an “enhanced” interaction. Cold severity was assessed twice daily. Patients randomized to practitioner visits used the Consultation and Relational Empathy (CARE) measure to rate clinician empathy. Interleukin 8 (IL-8) and neutrophil counts were obtained from nasal wash at baseline and 48 hours later.

Results

Patients’ perceptions of the clinical encounter were associated with reduced cold severity and duration. Encounters rated perfect on the CARE score had reduced severity (Perfect: 223, sub-perfect: 271, p=0.04) and duration (Perfect: 5.89 days, sub-perfect: 7.00 days, p=0.003). CARE scores were also associated with a more significant change in IL-8 (Perfect: mean IL-8 change 1586, sub-perfect: 72, p=0.02) and neutrophil count (Perfect: 49, sub-perfect: 12, p=0.09).

Conclusions

When patients perceive clinicians as empathetic, rating them perfect on the CARE tool, the severity, duration and objective measures (IL-8 and neutrophils) of the common cold significantly change.

Practice Implications

This study helps us understand the importance of the perception of empathy in a therapeutic encounter.

Keywords: patient-practitioner interaction, therapeutic encounter, empathy, CARE, common cold

1. Introduction

Pill or process? Often that which gets the most credit in facilitating healing is the pill that is prescribed. But what about the process that occurs prior to the prescription? The interaction between patient and health care practitioner can have significant healing influences. [The word “practitioners” throughout this paper refers to health care providers. In this study practitioners are primary care clinicians who provided study-related office visits.]

Empathy can be defined as a ‘cognitive attribute that involves an understanding of experiences, concerns and perspectives of the patient, combined with a capacity to communicate this understanding.[1] We believe the clinician who conveys empathy is able to create insight into the patient’s experience as if he/she were experiencing it themselves. In order to be perceived as empathetic, the clinician then must be able to communicate this understanding, verbally and/or non-verbally, to the patient. This can be therapeutic in itself.

Patient-practitioner interactions have been discussed at length in the literature. [2-7] A review of 25 randomized trials stated, “One relatively consistent finding is that physicians who adopt a warm, friendly, and reassuring manner are more effective than those who keep consultations formal and do not offer reassurance.”[8]

A retrospective analysis of psychiatrists treating patients with depression reported that practitioners who created a bond had better results in treating depression with placebo than did psychiatrists who used active drug but did not form a bond.[9] Thomas reported the results of a trial that randomized 200 consecutive patients with physical complaints but “no definite diagnosis” to a prescription for a placebo pill or no prescription, and to either a “positive” or a “non-positive” interaction. Although prescribing the placebo pill had no effect, 64% of those in the positive consultation group reported recovery, compared with 39% in the negative consultation group when evaluated after two weeks (p<0.01).[10] Kaptchuk et al. reported a three-armed randomized trial among 262 patients with irritable bowel syndrome that compared an “augmented” clinician visit incorporating sham acupuncture with a warm, empathetic, confident patient-practitioner interaction to a “limited” visit with sham acupuncture alone to a waiting list control group. At three weeks, 62% of patients in the augmented group reported adequate relief of symptoms compared to 44% in the limited group and 28% in the control group. [11] There has been limited research evaluating objective biomarkers with subjective symptom scores.

The intent of our study was to replicate Thomas’ and Kaptchuk’s findings by evaluating the effects of patient-practitioner interaction using the common cold as a model and by including objective laboratory measures. Patients with colds were invited to participate in a study that would test the herbal medicine echinacea as a cold treatment. They were told that the study would also examine placebo effects (effects of pills that don’t have active ingredients) and the effects of various ways that practitioners interact with their patients.

Preliminary results prior to un-blinding of this study have been published elsewhere showing similar findings.[12] This study adds to that paper since it includes the full research sample after un-blinding that allows association of causality. The previously published paper describes a prospective cohort, while this paper reports on a randomized controlled trial that confirms and extends the results while validating the methodology.

2. Methods

2.1 Design overview

This study was approved by the University of Wisconsin Health Sciences IRB. A summary of the methodology has been published previously. [13] The purpose of the study was three-fold, to evaluate the effects of patient-practitioner interaction, placebo pills, and the herbal therapy echinacea. Non-specific variables are those things that appear more peripheral to disease outcome, yet may also influence it. Non-specific variables are removed in placebo controlled trials, and their potential positive effects are rarely defined or appreciated. We hypothesized that a clinician visit that was “enhanced” through incorporation of non-specific variables (i.e., positive prognosis, empathy, empowerment, connection, and education) would result in a shorter duration and reduced severity of the common cold.

Results attributable to being randomized to placebo pills or echinacea arm will be published separately and their effects were controlled for in the statistical analysis of the data.

2.2 Setting and participants

Study participants were recruited from the community and seen either at the UW-Health Verona family medicine clinic or in the employee health clinic of St. Mary’s Hospital in Madison, Wisconsin. The practitioners did not have a previous relationship with the participants. [“Study participants” or “participants” refer to the patients who signed consent forms (or assent forms in the case of minors) to participate in the study.]

From June of 2004 to August of 2008, study coordinators enrolled 719 subjects. Participants 12 years or older were recruited to call a number if they were having new onset cold symptoms. Eligibility screening required patients to answer “yes” to one of two questions: “Do you think you have a cold?” or “Do you think you are coming down with a cold?” The person then had to answer “yes” to at least one of the following four symptoms established previously as the Jackson criteria:[14,15] (1) nasal discharge (2) nasal obstruction (3) sneezing or (4) sore throat. Symptoms had to start no more than 36 hours prior to enrollment. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, use of antibiotics, decongestants, antihistamines, echinacea, zinc, vitamin C or a combination cold formula. To prevent confusion with allergies, those with a history of allergies or asthma with current symptoms of allergic rhinitis, cough, shortness of breath, sneezing, nose or eye itching were excluded.

2.3 Randomization and interventions

The University of Wisconsin Hospitals Pharmaceutical Research Center Investigational Drug Service provided sealed envelopes with randomization assignments. Although the consent form contained information that we were studying patient practitioner interactions, study personnel emphasized that this was a placebo controlled study evaluating the effects of echinacea on the common cold.

Study staff saw participants three times: at baseline, approximately 48 hours later, and at the end of their colds. One-third of participants did not see a practitioner. Two-thirds were randomized to be seen by a practitioner only once at the initial visit. The practitioner was notified of the visit type before entering the exam room by opening an envelope that directed the visit type as ‘standard’ or ‘enhanced.’ A stopwatch was used to record the length of the visit.

Group 1 (No practitioner visit)

There was no practitioner encounter. This group received the standard protocol with baseline assessment, nasal washes and follow up at the end of the cold with study staff.

Group 2 (Standard Visit)

This visit type included history of present illness, past medical history, focused physical exam and diagnosis. Effort was made not to create a bond or a connection with the participant by keeping the visit short, with limited touch and eye-contact.

Group 3 (Enhanced Visit)

This visit type included the ingredients noted above but was enhanced using components thought to have healing effects.[16-36] These are summarized using the mnemonic PEECE: (P) Positive prognosis, (E) Empathy, (E) Empowerment, (C) Connection and (E) Education. Positive prognosis involved conveying a positive attitude through statements such as: “Your cold is likely to resolve in the next few days. Generally, colds last only six days or so.” Empathy was communicated through attentive listening with caring facial expression and comments relevant to a patient’s concerns such as, “Yes, a cold can really sap your energy.” Practitioners sought to empower patients through comments such as, “You can really make a difference in your cold by getting a good night’s sleep.” The practitioners promoted a connection with their patients via eye contact, a handshake greeting, humor when appropriate, and patient-oriented social and interactive discussion. Education on colds was tailored to the individual. It included the likely cause and length of the illness as well as responding to questions, e.g., “Yes, it’s good to exercise but try not to overdo it.” Personalized comments such as this were handwritten on information sheets for the patients. These PEECE components have been described more fully in a previous publication.[13] Effort was made to create a connection with the participant with the goal of “stacking the deck” incorporating eye-contact, touch and more time for relationship building.

Six practitioners (three authors of this manuscript and three of their colleagues) provided study-related patient visits. They first completed training with a medical anthropologist acting coach to maintain consistency in the type of visit assigned. Four practitioners were male and two female. Five were family physicians and one was a family nurse practitioner. Patients were scheduled indiscriminately with a study clinician who was available at the time they came in. All six study clinicians provided both standard and enhanced visits. The “mind set” used prior to a standard visit was, “no connection.” The mind set prior to an enhanced visit was to “make a connection.” Each practitioner could reference a written guide or “cheat sheet” as a reminder of the key ingredients of an enhanced or a standard visit. A patient handout that described the symptoms of a cold and the average duration of each was used only with the enhanced visit to educate the patient and provide positive prognosis (e.g., The average cold lasts 7-8 days, but with your healthy habits yours may only last 5-6 days). A review of videotaped encounters by outside assessors affirmed the validity of the standard and enhanced visits. Two coders, blinded to the group assignment, independently assessed the videotaped encounters as either standard or enhanced. Their coding disagreed for only one visit.

2.4 Outcomes and follow-up

Primary outcomes were the patient reported severity and duration of the cold. We identified duration as the time of enrollment until the participant first answered “no” to “Do you think you still have a cold?” for two days in a row. The last “yes” to that question marked the last time we considered the participant to still have a cold. If the cold continued for 14 days without a “no,” we documented the cold as lasting 14 days.

We evaluated the participants’ perceived severity of illness using the Wisconsin Upper Respiratory Symptom Survey (WURSS-21), an illness-specific quality of life instrument developed and validated by our research group.[37-40] This tool evaluates both severity of cold symptoms and quality-of-life functional impact.

Participants filled out the WURSS-21 twice daily, which allowed assessment of both patient reported severity and duration by calculating the area under the curve (AUC). [41] The subject’s perception of the clinical encounter was assessed using the Consultation and Relational Empathy (CARE) questionnaire that is designed to measure key non-specific factors of the practitioner-patient encounter.[42,43] Participants filled this out only once, immediately after their standard or enhanced visit. CARE assesses whether the practitioner, 1) made them feel at ease, 2) allowed them to “tell their story,” 3) really listened, 4) were interested in them as a whole person, 5) fully understood their concerns, 6) showed care and compassion, 7) were positive, 8) explained things clearly, 9) helped them take control, and 10) helped create a plan of action. A score of 1 (poor) to 5 (excellent) is awarded to each of the 10 items described above with a score range from 10-50. To supplement the CARE measure, we added two questions: “How much did you like this doctor?” and “How connected did you feel to him/her?” Response options followed a 5-point Likert scale: 1) very little, 2) not very much, 3) somewhat, 4) quite a lot, 5) very much.

We assessed biomarkers of the immune response and inflammation (Interleukin-8 and neutrophil count) by nasal washings at baseline and after 48 hours.

Secondary outcomes included information from validated questionnaires to assess the potential influences of confounding variables on the practitioner-patient interaction. These included evaluation of perceived stress (PSS-4),[44] general quality of life (physical and mental subscales of the SF-8),[45] the feeling thermometer[46] and optimism (LOT)[47].

2.5 Statistical analysis

A target sample size of 720 subjects was based on 80% power to detect 20% differences in severity-weighted days of illness (AUC) between allocation groups. This assumed a p value cut off of 0.05; proportionally stable standard deviation, and one-sided comparison. Estimation of power was based on data collected from previous studies using the WURSS instrument to evaluate Echinacea and the common cold.[38,39,48,49]

Standard statistical characteristics including mean, standard deviation and confidence interval were calculated. One-way ANOVA was used for multiple mean comparisons. Linear regression further assessed the relationship between the CARE measure and overall cold severity (AUC), controlling for possible confounding variables. A Cox-proportional hazard model assessed the duration of the cold by looking at the rate at which colds are ending based on the level of the CARE measure controlling for confounders. Confounders included age, gender, race, education, optimism, perceived stress, time from first symptom to enrollment and both pill and visit type group randomization.

3. Results

3.1 Baseline study population

719 patients were randomized to no visit (236), standard visit (246) or an enhanced visit (237). 713 completed the study with only 2 lost to follow up and 4 withdrawing from the study. (Figure 1) The majority of the subjects were white (82%) women (64.1%), with at least some college education (84%). The mean age was 33.7 years. Baseline distributions of age, gender, race, income, education and smoking status were similar in the three groups. (Table 1). There was no significant difference in subjects’ optimism or perceived stress at baseline. There was also no significant difference in symptom severity at baseline between groups (No visit WURSS-21; 41.84 (1.53), Standard Visit WURSS-21; 43.13 (1.61), Enhanced Visit WURSS-21; 42.87 (1.53)).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study participants

Table 1.

Demographics at Baseline

| Characteristics | All (719) | No Visit (n=236) |

Standard (n=246) |

Enhanced (n=237) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (SD) | 33.72 (14.41) | 32.86 (13.93) | 33.90 (14.10) | 34.31 (15.18) |

| Female | 461, 64.1% | 160, 67.8% | 154, 62.6% | 147, 62.0% |

| Non-White | 87, 12.1% | 28, 11.4% | 28, 13.1% | 31, 11.9% |

| Income < $25,000 | 244/680, 35.9% | 87/227, 38.3% | 78/232, 33.6% | 79/221, 35.7% |

| Education with “some college” |

567/675, 84.0% | 200/231, 86.6% | 186/228, 81.6% | 181/216, 83.8% |

| Smokers | 92/718, 12.8% | 24/235, 10.2% | 32/246, 13% | 36/237, 15.2% |

| Optimism (LOT) mean (std) and (CI) |

22.98 (4.03) (22.42-23.54) |

22.51 (4.0) (21.97-23.06) |

22.60 (4.06) (22.03-23.17) |

|

| Perceived Stress (PSS) Mean (std) and (CI) |

5.36 (2.98) (4.95-5.77) |

5.22 (2.99) (4.81-5.63) |

5.11 (3.23) (4.67-5.55) |

3.2 Primary outcomes

Observed primary outcomes suggested modest reductions in patient reported severity and duration for the enhanced group, compared to no visit or standard as measured by the sample mean values. While not statistically significant, trends were consistent across duration and severity, and were in the direction hypothesized (Table 2). Mean duration of illness was 6.51 days in the enhanced group, compared to 6.96 in the standard visit and 6.75 in the no visit group. Between-group differences in area under the time severity curve followed the same trends, but were marginal.

Table 2.

Outcomes By Treatment Group (mean (std) followed by confidence interval)

| Characteristics | No Visit | Standard | Enhanced | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health status | ||||

| WURSS-21 (Severity) | 262.19 (214.18) n=230, (232.24, 292.15) |

262.97 (206.03) n=246, (235.11 290.83) |

257.07 (224.33) n=237, (226.16 287.98) |

0.95 |

| WURSS-21 (Duration in Days) |

6.75 (3.50) n= 230, (6.26, 7.24) |

6.96 (3.36) n=246, (6.51, 7.42) |

6.51 (3.58) n=237, (6.02, 7.01) |

0.36 |

| Psychosocial | ||||

| Empathy (CARE) Scores |

N/A | 35.36 (9.58) n=244 (34.17, 36.56) |

45.65 (5.19) n=237 (44.99, 46.30) |

<0.001 |

| Liking clinician | N/A | 3.60 (0.91) n=243 (3.48, 3.72) |

4.51 (0.65) n=236 (4.42, 4.60) |

<0.001 |

| Connectedness to Clinician |

N/A | 2.88 (1.10) n=243, (2.74, 3.01) |

3.95 (0.90) n=236, (3.84, 4.07) |

<0.001 |

| Objective Markers | ||||

| IL-8 change | 134.1 (3940), n=221, (−428.13, 696.24) |

230 (6562) n=234, (−679.9, 1140) |

628 (4767), n=216, (−60,1316) |

0.58 |

| Neutrophil Count Change |

−3.48 (181.40) n=213, (−29.85, 22.88) |

11.95 (217.13) n=224, (−18.82, 42.72) |

28.89 (169.77) n=211, (4.10, 57.68) |

0.22 |

| Length of Visit | N/A | 3:43 mins (1:06) n=233 |

8:34 mins (2:12) n=224 |

<0.001 |

p-values are based on one-way ANOVA for available data.

Randomization to an enhanced patient-oriented clinical interaction led to a mean score of 45.6 on the CARE measure, compared to 35.4 in the standard group (p<0.001). The subjects rated 23/245 clinician encounters (9%) perfect on the CARE tool in the “standard” visit group while 89/235 (38%) rated the clinician perfect in the “enhanced” group (p<0.001)

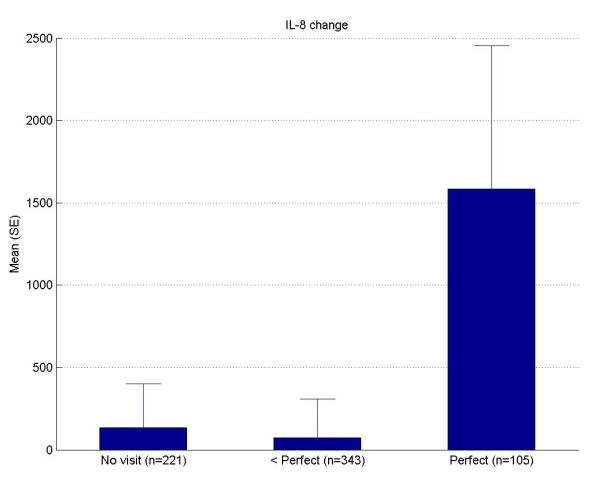

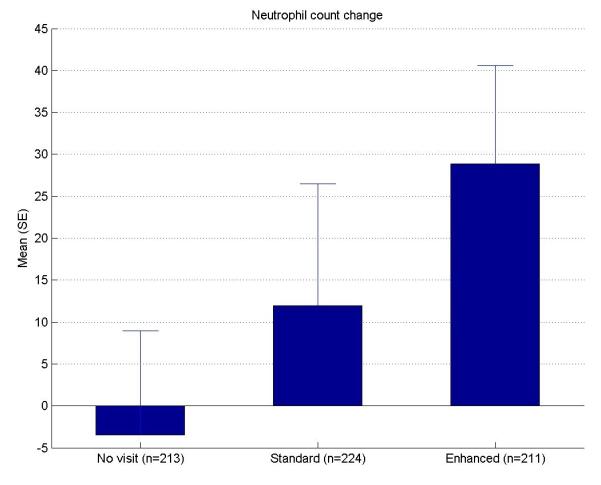

Although variability was high and statistical significance was not reached, there was a graduated response with greater change of IL-8 and neutrophil counts from no visit to standard visit to enhanced visit. (Table 2, Figure 2A and 2C) The length of the enhanced visit was also significantly longer than the standard visit by approximately 5 minutes (Standard 3:43, enhanced 8:34). (Table 2)

Figure 2.

A: Change in IL-8 for “no visit,”“standard visit” and “enhanced visit” types.

B: Change in IL-8 for “no visit,” “<perfect” and “perfect” visits as perceived by patients

C: Change in Neutrophil count for “no visit,”“standard visit” and “enhanced visit” types.

D: Change in Neutrophil count for “no visit,”“<perfect” and “perfect” visits as perceived by patients.

Evaluation of the CARE scores revealed that the ability of perfect CARE scores to predict subsequent cold outcomes appeared even more robust with statistical significance. Of the 483 subjects seen by a clinician, 112 interactions were given a perfect score. Those subjects rating the clinician as perfect on the CARE empathy tool showed a reduction in patient reported cold severity by 17.4% compared to sub-perfect scores (Perfect: 223.4, sub-perfect: 270.6, p=0.04) and a reduction in duration by 1.11 days (Perfect: 5.89 days, sub-perfect: 7 days, p=0.003). (Table 3, Figure 3) Relationships were found only when perfect and sub-perfect scores were dichotomized with no clear “dose-response” effect.

Table 3.

Empathy Scores (CARE). Comparison between no visit, sub-perfect and perfect scores.

| Characteristics | No Visit (n=236) |

Sub- Perfect CARE score (n=371) |

Perfect CARE score (n=112) |

*P values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health status | ||||

| WURSS-21 (Severity) |

262.19 (214.18) n=230 |

270.58 (218.45) n=369 |

223.38 (97.14) n=112 |

0.04 |

| WURSS-21 (Duration) |

6.75 (3.50) n= 230 |

7.00 (3.46) n=369 |

5.89 (3.36) n=112 |

0.003 |

| Feeling Thermometer Day 2 |

59.92 (18.04) n=228 |

57.88 (18.05) n=363 |

55.89 (18.74) n=108 |

0.31 |

| Psychosocial | ||||

| Connectedness to Clinician |

N/A | 3.10 (1.07) n=366 |

4.39 (0.74) n=112 |

<0.001 |

| Liking Clinician | N/A | 3.80 (0.88) n=366 |

4.87 (0.37) n=112 |

<0.001 |

| Objective Markers | ||||

| IL-8 change | 134.1 (3940), n=221 |

72 (4372.6) n=343 |

1585.5 (8884.2) n=105 |

0.02 |

| Neutrophil Count Change |

−3.48 (181.40) n=213 |

11.93 (200.58) n=333. |

49.42 (177.68) n=100 |

0.09 |

p-values are only for testing the differences between perfect score and less than perfect score.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meir Survival Curve showing time to end of cold for sub-perfect and perfect CARE scores.

The perfect CARE empathy score was also associated with a larger change in the immune markers IL-8 and neutrophil count when baseline levels were compared to levels approximately 48 hours later. (Table 3) Subjects who gave the clinician a perfect score had a significantly higher change in both nasal neutrophils (sub-perfect: 11.93 vs. perfect: 49.42, p=0.09) and the cytokine, IL-8 (sub-perfect,: 72 vs perfect: 1585.5, p=0.02). (Figure 2B and 2D)

Including possible confounding variables (age, gender, race, education, optimism, perceived stress, time from first symptom to enrollment and randomization to pill and visit groups) in the assessment of perfect CARE score with severity and duration outcomes did not affect the direction or significance of the relationships. Among perfect score subjects, mean AUC values were 72.38 lower (p=0.018), and colds ended at a higher rate in the survival analysis (β=0.46, p=0.001). See Tables 4 and 5 for details.

Table 4.

Linear regression of overall cold severity (AUC)

| Variable | Coefficient | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Perfect CARE | −72.3804 | 0.0184 |

| Age | 1.943421 | 0.017 |

| Female | 49.45473 | 0.0314 |

| White | 34.48774 | 0.3741 |

| College/postgraduate | −18.7801 | 0.413 |

| Optimism | −1.02771 | 0.7454 |

| Perceived stress | −5.71689 | 0.1787 |

Also controlling for time from first symptom to enrollment and both pill and visit type group randomization.

Table 5.

Cox-proportional hazard model of rate at which colds are ending

| Variable | Coefficient | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Perfect CARE | 0.45971 | 0.0013 |

| Age | −0.00881 | 0.016 |

| Female | −0.26571 | 0.0122 |

| White | −0.35091 | 0.0444 |

| College/postgraduate | −0.04817 | 0.6503 |

| Optimism | 0.00937 | 0.4999 |

| Perceived stress | 0.006471 | 0.7379 |

Also controlling for time from first symptom to enrollment and both pill and visit type group randomization.

3.3 Secondary outcomes

There were no statistically significant differences between the no-visit, standard and enhanced groups, or the no-visit, perfect and sub-perfect CARE score groups when the following was measured; optimism (LOT), perceived stress (PSS), mood states (Feeling thermometer) and the short form mental and physical assessment (SF-8; MCS, PCS).

Outcomes data did not suggest that there was any one practitioner who had high or low scores suggesting that there was not a significant practitioner effect among the six clinicians.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

4.1 Discussion

This study was able to correlate objective findings (IL-8 and neutrophil counts) to the subjective measures of cold duration and severity and perception of empathy during a clinical encounter. IL-8 and neutrophils have been associated with a more robust immune response to viral infections.[50,51] The amount of change of IL-8 and neutrophil levels was greater for the “enhanced” and “perfect CARE score” groups. (Figure 2) This finding not only helps expand our knowledge of how these immune markers change with the common cold, but also shows that the patient’s perception of a practitioner in a clinical encounter can translate to physical immune changes. The most significant change in IL-8 was in the “perfect CARE score” (50/50 on CARE score) where the clinician was rated as perfect on empathy, compassion and willingness to listen (p=0.02). The “perfect” group was also associated with the shortest cold duration (5.89 days in for perfect vs 7.00 days for non-perfect) with less severe colds (17% reduction) when compared to the non-perfect CARE scores (223.38 in perfect vs 270.58 in non-perfect).

Although not statistically significant, the enhanced visit compared to the standard visit did show a trend towards a shorter duration (−0.45 days) of the common cold. The improvement in severity was minimal at 2%. The largest findings were found when the patient perceived the visit high in empathy. Was this effect influenced most by the empathy in the clinic encounter or the degree of optimism from which the patient perceived the world? Since 9% of the “standard” visits were rated “perfect” on the CARE score, it may be beneficial to immunity to see others in a positive light even if the other person is conveying a message that does not deserve it. If this was the case, we would have seen a higher level of optimism in those with more robust responses and this was not the case. We also found no significant difference in age, race, income, education, smoking or perceived stress. After controlling for confounding variables, the positive effects on patient reported cold severity and duration remained. This suggests that the results were more related to how the clinical interaction was perceived, than the optimism of the individual.

Another possible explanation for these findings would be that the patients who rated the visit perfect on the CARE score may have had less severe symptoms. If they had been feeling better, they may have been more likely to rate the encounter higher. However, this study showed no difference in baseline WURSS-21 cold severity between the perfect CARE scores (43.27 (2.48)) and < perfect CARE scores (42.69 (1.23)).

The difference between the findings seen in the “enhanced” visit group and the “perfect CARE score” group is that in the “enhanced” visit we looked at how a specific clinical visit influences the patient reported severity and duration of the common cold. But in the “perfect CARE score” group, we looked at the patient’s perception of practitioner empathy. The patient’s perception of the visit appears to be a significant factor. A practitioner may think that she/he is providing a clinical visit that is rich in empathy and compassion, but this has less of an influence if the patient does not perceive it as such. Empathy requires that the clinician be able to communicate to the patient that they understand what the patient is going through. The “perfect CARE” scores suggest that empathy was communicated appropriately to warrant this patient perception. It appears that patient perception is a key domino that triggers a cascade of self-healing influences that have a large effect on the common cold.

Although possibly related to chance, the duration of the cold was shorter for those patients who saw no clinician compared to the “standard” (no visit: 6.75 days vs standard: 6.96 days) or “sub-perfect” visits (no visit: 6.75 days vs sub-perfect: 7.00 days). This would stress the importance of practitioner wellness since having a clinician who is burnt-out or non-empathetic may cause more harm than seeing no practitioner at all.

The practitioners in this study were new to the patients, so there was no pre-existing relationship. Having a prior relationship with a clinician who is seen as caring and attentive to their needs may enhance the benefit.

The study staff was also kind and compassionate. It is hard to decipher what effect this may have had on subjects’ perception of their care. Ideally, all the interactions with the patients would have been “standard” or “enhanced” to look at the full potential of an “enhanced” visit. In pragmatic clinical settings, it is not just the clinician who can influence a positive perception, but all other clinic staff as well.

More studies are needed to further evaluate the ingredients of a clinical encounter that are associated most with a “perfect” empathy perception so the various communication methods and relationship skills can be taught and reproduced. Further research will also verify if results will be replicated in populations with different demographics.

4.2 Conclusion

This was a large, well-powered study with excellent subject retention. The results suggest that positive patient perception of practitioner empathy can have significant effects on reducing the duration and patient reported severity of the most common infectious disease on the planet.

4.3 Practice implications

This study helps us understand the importance of human interaction in a therapeutic encounter. Having a practitioner who can create a bond with patients while listening and conveying empathy and compassion may reduce the patient reported severity and duration of the common cold with little potential for harm. This effect is enhanced when patients perceive their care as perfect in these basic human attributes.

Acknowledgements

This trial was sponsored by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine at the National Institutes of Health (NIH NCCAM 1-R01-AT-1428). The University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health and the University of Wisconsin Department of Family Medicine have also invested substantially in this trial, particularly in the support of D. Rakel and B. Barrett. Support for Dr. Barrett’s conception of the original trial came from a K-23 career development grant from NIH NCCAM and a career development grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Generalist Physician Scholars Program. MediHerb®, Australia, supplied echinacea and matching placebo.

Special thanks to Charlene Luchterhand in helping prepare the manuscript and coinvestigators, David Rabago, Raandi Schmidt, Gay Thomas, and Shari Barlow. Thanks also to Ted Kaptchuk and Stewart Mercer for reviewing the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- WURSS-21

Wisconsin Upper Respiratory Symptom Survey

- AUC

(Area-under-the-curve)

- CARE

Consultation and Relational Empathy Measure

- PSS-4

Perceived Stress Scale

- SF-8

Short Form-8 Health Survey

- LOT

Life Orientation Test

- IL-8

Interleukin-8

Footnotes

Conflict of interest All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest regarding this manuscript.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00065715.

References

- 1.Hojat M. Empathy in patient care. Springer; New York City: 2007. p. 80. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Covington H. Caring presence. Delineation of a concept for holistic nursing. J Holist Nurs. 2003 Sep;21:301–17. doi: 10.1177/0898010103254915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beach MC, Inui T. Relationship-Centered Care Research Network. Relationship-centered care. A constructive reframing. J Gen Intern Med. 2006 Jan;21(Suppl 1):S3–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00302.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borrell-Carrio F, Suchman AL, Epstein RM. The biopsychosocial model 25 years later: principles, practice, and scientific inquiry. Ann Fam Med. 2004 Nov-Dec;2:576–82. doi: 10.1370/afm.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller FG, Kaptchuk TJ. The power of context: reconceptualizing the placebo effect. J R Soc Med. 2008 May;101:222–5. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2008.070466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brody H. Placebo response, sustained partnership, and emotional resilience in practice. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1997 Jan-Feb;10:72–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benson H, Friedman R. Harnessing the power of the placebo effect and renaming it “remembered wellness”. Annu Rev Med. 1996;47:193–9. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.47.1.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Di Blasi Z, Harkness E, Ernst E, Georgiou A, Kleijnen J. Influence of context effects on health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet. 2001 Mar 10;357:757–62. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04169-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKay KM, Imel ZE, Wampold BE. Psychiatrist effects in the psychopharmacological treatment of depression. J Affect Disord. 2006 Jun;92:287–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas KB. General practice consultations: is there any point in being positive? Brit Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1987 May 9;294:1200–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.294.6581.1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaptchuk TJ, Kelley JM, Conboy LA, Davis RB, Kerr CE, Jacobson EE, Kirsch I, Schyner RN, Nam BH, Nguyen LT, Park M, Rivers AL, McManus C, Kokkotou E, Drossman DA, Goldman P, Lembo AJ. Components of placebo effect: randomised controlled trial in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Brit Med J. 2008 May 3;336:999–1003. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39524.439618.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rakel DP, Hoeft TJ, Barrett BP, Chewning BA, Craig BM, Niu M. Practitioner empathy and the duration of the common cold. Fam Med. 2009 Jul-Aug;41:494–501. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barrett B, Rakel D, Chewning B, Marchand L, Rabago D, Brown R, Scheder J, Schmidt R, Gern JE, Bone K, Thomas G, Barlow S, Bobula J. Rationale and methods for a trial assessing placebo, echinacea, and doctor-patient interaction in the common cold. Explore (NY) 2007 Nov-Dec;3:561–72. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackson GG, Dowling HF, Muldoon RL. Acute respiratory diseases of viral etiology. VII. Present concepts of the common cold. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1962 Jun;52:940–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.52.6.940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackson GG, Dowling HF, Anderson TO, Riff L, Saporta J, Turck M. Susceptibility and immunity to common upper respiratory viral infections--the common cold. Ann Intern Med. 1960 Oct;53:719–38. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-53-4-719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsueh Y. The Hawthorne experiments and the introduction of Jean Piaget in American industrial psychology, 1929-1932. Hist Psychol. 2002 May;5:163–89. doi: 10.1037/1093-4510.5.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Starfield B, Wray C, Hess K, Gross R, Birk PS, D’Lugoff BC. The influence of patient-practitioner agreement on outcome of care. Am J Public Health. 1981 Feb;71:127–31. doi: 10.2105/ajph.71.2.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stewart M, Brown JB, Boon H, Galajda J, Meredith L, Sangster M. Evidence on patient-doctor communication. Cancer Prev Control. 1999 Feb;3:25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suchman AL, Markakis K, Beckman HB, Frankel R. A model of empathic communication in the medical interview. J Amer Med Assoc. 1997 Feb 26;277:678–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomas KB. The consultation and the therapeutic illusion. Brit Med J. 1978 May 20;1:1327–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6123.1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roter DL, Hall JA, Merisca R, Nordstrom B, Cretin D, Svarstad B. Effectiveness of interventions to improve patient compliance: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 1998 Aug;36:1138–61. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199808000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roter DL, Hall JA. Doctors Talking with Patients: Patients Talking with Doctors: Improving Communication in Medical Visits. Auburn House; Westport CT: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flood AB, Lorence DP, Ding J, McPherson K, Black NA. The role of expectations in patients’ reports of post-operative outcomes and improvement following therapy. Med Care. 1993 Nov;31:1043–56. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199311000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, Warner G, Moore M, Gould C, Ferrier K, Payne S. Observational study of effect of patient centredness and positive approach on outcomes of general practice consultations. Brit Med J. 2001 Oct 20;323:908–11. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7318.908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mondloch MV, Cole DC, Frank JW. Does how you do depend on how you think you’ll do? A systematic review of the evidence for a relation between patients’ recovery expectations and health outcomes. CMAJ. 2001 Jul 24;165:174–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petrie KJ, Weinman J, Sharpe N, Buckley J. Role of patients’ view of their illness in predicting return to work and functioning after myocardial infarction: longitudinal study. Brit Med J. 1996 May 11;312:1191–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7040.1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ryff CD. Positive Mental Health. In: Blechman EA, Brownell KD, editors. Behavioral Medicine and Women: A Comprehensive Handbook. Guilford Publications, Inc.; New York: 1998. pp. 183–8. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Savage R, Armstrong D. Effect of a general practitioner’s consulting style on patients’ satisfaction: a controlled study. Brit Med J. 1990 Oct 27;301:968–70. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6758.968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roter DL, Hall JA. Patient-Provider Communication. In: Glanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer BK, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice. Jossey-Bass, A Wiley Company; San Francisco: 1997. pp. 206–26. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Evans RG, Barer ML, Marmor TR. Why Are Some People Healthy and Others Not? The Determinants of Health of Populations. Aldine de Gruyter; Hawthorne, NY: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marmot MG. Social differentials in health within and between populations. Daedalus. 1994;123:197–216. [Google Scholar]

- 32.McKnight JL. Health and Empowerment. Can J Public Health. 1985 May-Jun;76(Suppl 1):37–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singer B, Ryff CD. Hierarchies of Life Histories and Associated Health Risks. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;896:96–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guadagnoli E, Ward P. Patient participation in decision-making. Soc Sci Med. 1998 Aug;47:329–39. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suchman AL, Matthews DA. What makes the patient-doctor relationship therapeutic? Exploring the connexional dimension of medical care. Ann Intern Med. 1988 Jan;108:125–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-108-1-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matthews DA, Suchman AL, Branch WT., Jr. Making “connexions”: enhancing the therapeutic potential of patient-clinician relationships. Ann Intern Med. 1993 Jun 15;118:973–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-12-199306150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barrett B, Locken K, Maberry R, Schwamman J, Brown R, Bobula J, Stauffacher EA. The Wisconsin Upper Respiratory Symptom Survey (WURSS): a new research instrument for assessing the common cold. J Fam Pract. 2002 Mar;51:265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barrett B, Brown RL, Mundt MP, Thomas GR, Barlow SK, Highstrom AD, Bahrainian M. Validation of a short form Wisconsin Upper Respiratory Symptom Survey (WURSS-21) Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009 Aug 12;7:76. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barrett B, Brown R, Mundt M, Safdar N, Dye L, Maberry R, Alt J. The Wisconsin Upper Respiratory Symptom Survey is responsive, reliable, and valid. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005 Jun;58:609–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barrett B, Brown R, Mundt M. Comparison of anchor-based and distributional approaches in estimating important difference in common cold. Qual Life Res. 2008 Feb;17:75–85. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9277-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lydick E, Epstein RS, Himmelberger D, White CJ. Area under the curve: a metric for patient subjective responses in episodic diseases. Qual Life Res. 1995 Feb;4:41–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00434382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mercer SW, Maxwell M, Heaney D, Watt GC. The consultation and relational empathy (CARE) measure: development and preliminary validation and reliability of an empathy-based consultation process measure. Fam Pract. 2004 Dec;21:699–705. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmh621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mercer SW, McConnachie A, Maxwell M, Heaney D, Watt GC. Relevance and practical use of the Consultation and Relational Empathy (CARE) Measure in general practice. Fam Pract. 2005 Jun;22:328–34. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmh730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cohen S, Williamson G. Perceived Stress in a Probability Sample of the United States. In: Spacapan, Shirlynn, Oskamp, Stuart, editors. The Social Psychology of Health. Sage Publications; Newbury Park, CA: 1988. pp. 31pp. 31–67. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Dewey JE, Gandek B. How to Score and Interpret Single-Item Health Status Measures: A Manual for Users of the SF-8 Health Survey. Quality Metric; Lincoln, RI: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Llach X Badia, Herdman M, Schiaffino A. Determining correspondence between scores on the EQ-5D “thermometer” and a 5-point categorical rating scale. Med Care. 1999 Jul;37:671–7. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199907000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994 Dec;67:1063–78. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barrett BP, Brown RL, Locken K, Maberry R, Bobula JA, D’Alessio D. Treatment of the common cold with unrefined echinacea. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2002 Dec 17;137:939–46. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-12-200212170-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barrett B, Brown R, Mundt M. Comparison of anchor-based and distributional approaches in estimating important difference in common cold. Qual Life Res. 2008 Feb;17:75–85. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9277-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Klemens C, Rasp G, Jund F, Hilgert E, Devens C, Pfrogner E, Kramer MF. Mediators and cytokines in allergic and viral-triggered rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2007 Jul-Aug;28:434–41. doi: 10.2500/aap.2007.28.3017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stoll D. Inflammatory acute rhinosinusitis. Presse Med. 2001 Dec 22-29;30:33–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]