Abstract

In this study it was planned to investigate the effect of oxidized phosphatidylcholine (derived from egg) feeding on lipid peroxidation of different tissues in rats. Male Wistar albino rats were fed oxidized and unoxidized phosphatidylcholine for 2 and 4 weeks, respectively. During the period of study food intake and body weights of animals increased gradually. Animals fed oxidized phosphatidylcholine for 2 and 4 weeks showed 33 and 15% spontaneous hemolysis of red blood cells in vitro. Under identical experimental conditions animals given unoxidized phosphatidylcholine showed 14.5 and 13.4% hemolysis for 2 and 4 week’s period, respectively. Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) level in thymus, spleen, kidney, heart, liver and lung significantly increased in rats given oxidized phosphatidylcholine as compared to unoxidized group. Furthermore, in oxidized phosphatidylcholine group TBARS values in kidney, liver and lungs continued to rise for 4 weeks of treatment while TBARS level in heart, spleen and thymus was found to be decreased at the end of 4 weeks of oxidized phosphatidylcholine feeding. Plasma triacylglycerol and cholesterol was found to increase in rats who had received oxidized phosphatidylcholine for 2 weeks. These findings suggest that excess and persistent intake of oxidized phosphatidylcholine can cause significant damage to organs.

Keywords: Lipid peroxidation, Oxidized phosphatidylcholine, Cholesterol, Triacylglycerol, TBARS, Hemolysis necrosis

Introduction

Lipid peroxidation, one of the major causes of food spoilage, leads to rancidity in foods containing fat. Numerous studies and biochemical investigations have suggested that lipid oxidation products, ingested with food or produced endogenously, represent a health risk [1, 2] and are implicated in several diseases such as cancer, atherosclerosis, inflammation and aging. Shimura et al. [3] reported the depression of lymphocyte functions by lipid peroxidation induced by cumene hydroperoxide in rats’ spleenocytes. Lee and Wan [4] reported that the short term supplementation of 233 mg of vitamin E to healthy subjects can modulate cell-mediated immunity and reduce oxidative stress.

Studies concerning lipid peroxidation have been mostly carried out with neutral lipids, especially with fats and oils [5, 6]. But little is known about the toxicity and nutritive problems associated with oxidized phospholipids. Phospholipids are essential components of lipid metabolism. They individually or in combination exert distinct influence upon emulsification, digestion and absorption of dietary lipids [7]. Phospholipids are present virtually in all foods [8], since they are the constituents of cell membranes in both plants and animals. They are widely used as multipurpose additives in the pharmaceutical and food industries. Phospholipids and its oxidized products have developed great interest in the field of medicine, nourishment, cosmetic and pharmaceutical industries [9–13]. Igene and Pearson [14] have pointed out that phospholipids are the contributors to oxidative rancidity in cooked meat. It has been reported that phospholipid fraction in chicken, beef, pork, lamb and sea foods are more prone to oxidation than triacylglycerols (TG) due to their relatively higher content of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) [15, 16]. Sessa and co-workers [17] have reported that soybean phosphatidylcholine (PC) develops bitter taste on autoxidation.

Phosphatidylcholine is well distributed in several foods. Egg yolk, organ meats, spinach and wheat germ are its good sources. Phosphatidylcholine from different sources are used as food additives and as nutrition supplements [18, 19]. It is also used therapeutically to treat dementia, liver fibrosis and cirrhosis [18, 20]. Phosphatidylcholine can be easily oxidized during storage, processing and exposure to air by unregulated free radical reactions and thus may rapidly loose its activity. However, it is not very certain that which specific oxidation product of phospholipid is cytotoxic [21]. The present study was conducted to evaluate the toxicity of PC because of its wide applications as well as its nature to form highly toxic products. It was desirable to see the effect of oxidized PC in weanling rats and its subsequent effect on immunocompetent cells (thymus, spleen).

Materials and Methods

Phosphatidylcholine and thiobarbituric acid (TBA) were purchased from E. Merck, Germany and BDH Chemical, Poole, UK, respectively. Anhydrous sodium dihydrogen phosphate and disodium hydrogen was the product of Fluka, Switzerland. Enzymatic kits for the estimation of TG and cholesterol were from Sclavo, Spa, Milan, Italy. All the other chemicals used were of analytical grade. Solvents were distilled and dried prior to use.

Peroxidation of Phosphatidylcholine for Oral Intubation

Egg PC was dispersed on a petri dish and stored at 25–30°C for 2 months with frequent stirring and mixing using a glass rod. After the incubation period, the sticky brown colored PC was found to have 1200 mg/kg thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS), determined by the modified method of Yoshida and co-workers [22]. The oxidized PC was then stored at −20°C and used for oral intubation.

To obtain a uniform emulsion of oxidized PC for oral feeding, the PC (10 g) was mixed with milk (50 g) and the mixture was heated at 40oC for 10 min with frequent stirring. The resulting emulsion sufficient for 1 day’s feeding was kept in small amber colored bottle. Each bottle was flushed with nitrogen gas and stored at −20°C for no longer than 7 days. There was no significant difference in TBARS value of the PC emulsion during storage at −20°C as compared to freshly prepared PC emulsion. Treated animals were given 4.4 × 10−3 g of oxidized PC/g body weight.

Fatty Acid Analysis

Fatty acids of oxidized and unoxidized PC were converted to methyl esters for Gas Liquid chromatography (GLC).

Preparation of Methyl Esters

Phosphatidycholine samples (30–50 mg) were taken in a Teflon coated screw capped Pyrex glass tubes and esterified with 10 ml of freshly prepared methylating reagent (methanol: sulphuric acid: benzene, 85:4:10, v/v) as described by Ahmed et al. [23]. The resulting methyl esters were dissolved in dry hexane, purified by thin layer chromatography and analyzed by GLC.

GLC Analysis of Fatty Acids

The fatty acid methyl esters were quantitatively identified by GLC using Hewlett-Packard 5048A gas chromatograph. The chromatograph was equipped with 2 mm i.d. × 10 ft column, packed with 5% DEGS-PS on 80–120 mesh, supelcoport. Nitrogen was the carrier gas and used at a flow rate of 20 ml/min. Both the injection and detector were maintained at 250°C. The column temperature was 120–250°C with a temperature programming of 2°C/min. Fatty acids methyl esters in the samples were identified by comparing the retention time with authentic reference standard mixtures integrated by a computing integrator. Figures reported are area percent of the individual peaks.

Animals and Diet

Twenty-eight days old male albino Wistar rats weighing 99.9 g ± 2.15 (Mean ± S.E.) were obtained from the Animal Care Center, King Saud University, Riyadh. They were individually housed in stainless steel cages in a room maintained at 25 ± 2°C with a controlled photo period of 12 h/day. Rats were randomly divided into four groups (six animals/group). They were fed with a commercial pelleted rat chow (Grain silos, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia) and provided with water ad libitum. Oxidized PC (4.4 × 10−3 g/g body weight) was given orally by intubation to the animals of Group II and IV for the period of 2 and 4 weeks respectively on alternate days. Control animals of Group I and III received the same amount of fresh PC in milk for 2 and 4 weeks respectively. Food intake and body weight of the animals were also recorded on alternate days.

Blood, Tissue Collection and Sample Preparation

After 2 and 4 weeks of dietary treatment, the rats were food deprived for 12 h and anesthetized using diethylether (B.D.H. Chemicals Poole, UK). Blood was collected in heparinized vacutainer tubes (Becton–Dickinson Co., Rutherford, NJ) by cardiac puncture. The heparinized blood was gently mixed and centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 15 min (Model RT6000D & T6000D, Sorvall table top centrifuge, Du Pont Company, Wilmington, USA) to separate plasma and red blood cell (RBC). Plasma was frozen for further analysis while in vitro hemolysis of RBC was carried on the same day. Thymus, spleen, liver, lung, kidney and heart were swiftly excised and tissues were washed in ice-cold saline, dried, weighed and stored at −80°C till further analysis.

A portion of the tissues were later thawed, minced well and 10% (w/v) homogenate was prepared in ice-cold 0.01 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0 using a tissue homogenizer (Ultra-Turrax T25, Janke & Kunkel, IRA-Labortechnik). The homogenates were used for TBARS analysis.

Determination of In Vitro Hemolysis of RBC

Hemolysis of red blood cells was determined by the method of Draper and Csallany [24] as modified by Buckingham [25]. Red blood cells separated from plasma by centrifugation were washed three times with 0.9% saline. The washed RBCs were suspended at a concentration of 0.5% (v/v) in 0.01 M sodium phosphate pH 7.0 containing 0.15 M sodium chloride (PBS), at 37°C for 20 h and the absorbance was recorded at 540 nm against PBS. Percent hemolysis was measured by completely hemolyzing the same concentration of RBC in distilled water.

Assay for Lipid Peroxidation (TBARS)

The TBARS in tissue homogenates were measured using a modified TBA assay as previously described by Uchiyama and Mishara [26]. Modification of TBA assay was as follows: To a 0.5 ml of tissue homogenate (10%, w/v), 3.0 ml phosphoric acid (1%) was added, followed by 1.0 ml aqueous solution of TBA (0.6%). The mixture was heated in a boiling water bath for 45 min and after cooling to room temperature the product of TBA was extracted into 4.0 ml n-butanol. The n-butanol was separated by centrifugation at 2000 rpm for 10 min and the absorbance of butanol layer was recorded on a spectrophotometer (Ultrospec-lll, UV/visible spectrophotometer, Pharmacia, LKB) at 532 and 520 nm. The content of lipid peroxide as TBARS were calculated from the difference of absorbance, using MDA as standard and expressed as nmoles MDA/g wet tissue.

Lipid Analysis

Total lipids in tissue homogenates were extracted with chloroform: methanol (2:1 v/v) and washed according to the procedure of Folch et al. [27] and sonicated (Fisher, Sonic dismembrator, model 150) in saline. Triglyceride and cholesterol in plasma and tissue extracts (dissolved in 1.0 ml of saline) were estimated spectrophotometrically using commercial enzymatic kits.

Statistical Analysis

The standard errors of the means were calculated and the data were subjected to student’s t-test for statistical significance.

Results

Compositional Changes in PC During Oxidation

Egg PC on storage at 25–30°C for 8 weeks became highly rancid as evident from its obnoxious odor and TBARS value (1200 mg/Kg). The fatty acid composition and other chemical properties of PC are shown in Table 1. Comparing the fatty acid composition of oxidized PC and unoxidized PC, it was apparent that the content of total saturated acids was increased to 52.5% in oxidized PC as compared to 45.6% in unoxidized PC. Similarly, the total unsaturated acids were decreased in oxidized PC and the maximum decrease was observed in PUFA as they are more prone to autoxidation. In oxidized PC the linoleic acid (18:2) was decreased by 8.1% while docosahexaenoic acid (22:6) was decreased by 38.6%. The rate of deterioration of 22:6 compared to 18:2 was more because of its higher unsaturation.

Table 1.

Changes in fatty acid composition (wt%) of oxidized and unoxidized egg phosphatidylcholine (PC)

| Fatty acid | Oxidized PC | Unoxidized PC |

|---|---|---|

| 16:0 Palmitic acid | 34.2 | 32.0 |

| 18:0 Stearic acid | 18.3 | 13.6 |

| 18:1 Oleic acid | 31.1 | 32.0 |

| 18:2 Linoleic acid | 13.2 | 15.6 |

| 18:3 Linolenic acid | Traces | Traces |

| 22:6 Docosahexaenoic acid | 2.2 | 5.6 |

| Total saturated acids (%) | 52.5 | 45.6 |

| Total unsaturated acids (%) | 46.5 | 53.2 |

| Decrease in 18:2 (%) | 8.1 | |

| Decrease in 22:6 (%) | 38.6 |

Feeding and Growth

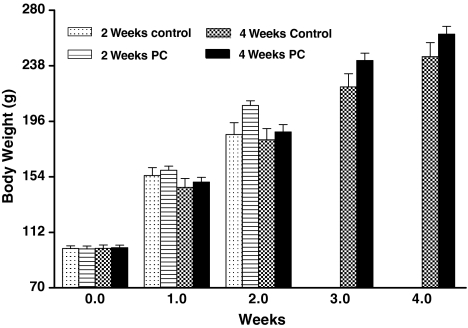

The average body weight of rats was 99.9 g ± 2.15 at the start of the experiment. Body weight and the food consumption of animals in all groups increased gradually for the period of 2 and 4 weeks as shown in Figs. 1 and 2. There was insignificant difference among the treated and control rats. The organs weight (liver, heart, kidney, lung, spleen and thymus) in each group are shown in Table 2, no significant difference in the weights of these organs were observed.

Fig. 1.

Effect of oxidized and unoxidized PC on the body weight of rats. Group I (control, 2 weeks), Group II (treated, 2 weeks), Group III (control, 4 weeks), Group IV (treated, 4 weeks)

Fig. 2.

Food consumption pattern of rats fed oxidized PC and their comparable groups. Group I (control, 2 weeks) and Group II (treated, 2 weeks); Group III (control, 4 weeks) and Group IV (treated, 4 weeks)

Table 2.

Mean organ weights (g) of rats of control and treated groups as affected by feeding oxidized PC for 2 and 4 weeks

| Tissue | Groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 weeks | 4 weeks | |||

| Group I (control) | Group II (treated) | Group III (control) | Group IV (treated) | |

| Thymus | 0.38 ± 0.03 | 0.34 ± 0.03 | 0.46 ± 0.04 | 0.48 ± 0.03 |

| Spleen | 0.94 ± 0.20 | 0.91 ± 0.15 | 1.25 ± 0.11 | 1.33 ± 0.20 |

| Heart | 0.69 ± 0.04 | 0.77 ± 0.03 | 0.72 ± 0.04 | 0.79 ± 0.05 |

| Kidney | 1.35 ± 0.04 | 1.57 ± 0.07 | 1.45 ± 0.04 | 1.64 ± 0.17 |

| Liver | 6.66 ± 0.23 | 7.68 ± 0.32 | 7.00 ± 0.60 | 7.90 ± 0.19 |

| Lung | 1.15 ± 0.12 | 1.19 ± 0.05 | 1.36 ± 0.27 | 1.20 ± 0.05 |

Each value represents the mean ± S.E. of n = 6 rats per group. Data were analyzed by Student’s t-test

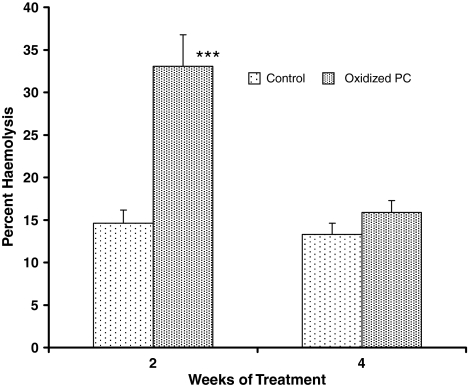

In Vitro Hemolysis of RBC

The spontaneous RBC in vitro hemolysis values of Group I and III (control animals) were 14.5 and 13.4% respectively. The percent hemolysis in Group IV animals (treated, 4 weeks) were not significantly changed (15%) as compared to control (Group III), but in Group II (treated, 2 weeks) a significant (P < 0.001) increase in the percent hemolysis (33%) was observed as compared to Groups I, III and IV animals (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Effect of oxidized and unoxidized PC on the rate of red blood cell hemolysis. Significantly different from its respective control at *** P < 0.001

Plasma and Tissue Lipids

Rats fed oxidized PC for 2 weeks (Group II) produced a significant increase in plasma TG (P < 0.01) and cholesterol (P < 0.05) content as compared to control (Group I). Treatment of rats for 4 weeks (Group IV) did not induce any marked changes in the level of cholesterol and TG. Cholesterol and TG level of the tissues (heart, liver and kidney) of all four groups are shown in Table 3. No significant differences were observed.

Table 3.

Mean plasma and organ lipid profile of control and treated rats at 2 and 4 weeks

| Groups | Cholesterol level | TG level | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma (mg/dl) | mg/g wet tissue | Plasma (mg/dl) | mg/g wet tissue | |||||

| Liver | Heart | Kidney | Liver | Heart | Kidney | |||

| 2 weeks | ||||||||

| Group I (control) | 32.0 ± 1.30 | 1.9 ± 0.24 | 1.6 ± 0.15 | 2.5 ± 0.25 | 39.0 ± 1.80 | 2.7 ± 0.36 | 1.4 ± 0.19 | 1.9 ± 0.34 |

| Group II (treated) | 42.0 ± 0.86* | 1.6 ± 0.33 | 1.8 ± 0.16 | 1.9 ± 0.24 | 54.0 ± 2.20** | 3.1 ± 0.36 | 1.4 ± 0.20 | 2.4 ± 0.29 |

| 4 weeks | ||||||||

| Group III (control) | 42.5 ± 1.40 | 1.6 ± 0.20 | 1.9 ± 0.17 | 2.3 ± 0.33 | 56.0 ± 2.30 | 2.5 ± 0.31 | 1.9 ± 0.40 | 2.3 ± 0.23 |

| Group IV (treated) | 42.6 ± 0.65 | 1.5 ± 0.08 | 1.7 ± 0.19 | 2.8 ± 0.16 | 44.0 ± 1.90 | 2.3 ± 0.25 | 1.58 ± 0.20 | 2.5 ± 0.24 |

Results are means ± S.E. of n = 6 rats/group. Data were analyzed by Student’s t-test. Significantly different from their respective control at * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01

TBARS Analysis in Tissues

The rats fed oxidized PC (Group II and IV) showed a marked and significant increase in TBARS in thymus, spleen, heart, kidney, liver and lungs compared to control (Group I and III)—Table 4. The increase in TBARS in spleen and heart of Group II (treated, 2 week) were significantly higher (P < 0.01) when compared to Group IV (treated, 4 week), while there was no significant difference in TBARS in kidney, liver, and lung. A marked increase in TBARS of thymus was observed in Group II (treated, 2 weeks) animals as compared to the thymus of animals in Group IV (treated, 4 week).

Table 4.

Mean TBARS in control and treated rat tissues at 2 and 4 weeks

| Tissue | MDA (nmoles/g wet tissue) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 weeks | 4 weeks | |||

| Group I (control) | Group II (treated) | Group III (control) | Group IV (treated) | |

| Thymus | 74 ± 12.9 | 260 ± 38.0** | 84 ± 21.0 | 200 ± 30.8* |

| Spleen | 206 ± 24.0 | 518 ± 32.0***,a | 198 ± 32.2 | 326 ± 40.8* |

| Heart | 246 ± 42.9 | 500 ± 30.9**,a | 238 ± 2.2 | 342 ± 23** |

| Kidney | 248 ± 31.7 | 430 ± 42.9** | 278 ± 33.8 | 486 ± 69* |

| Liver | 216 ± 16.2 | 346 ± 31.7** | 194 ± 12.9 | 384 ± 54** |

| Lung | 178 ± 10.2 | 248 ± 10.6*** | 156 ± 15.3 | 240 ± 20.5* |

Each value represents the mean ± S.E. of n = 6 rats/group. Data were analyzed by Student’s t-test. Significant increase compared to corresponding control at * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001. a Significantly different from Group IV at P < 0.01

Discussion

It has been widely suggested that feeding of autoxidized oils to rats have resulted in growth retardation, loss of appetite, necrotic changes in several tissues, cardiomyopathy, hemolytic anemia, diarrhea, etc., and accumulation of peroxides in several tissues [1, 28, 29]. Similarly, the oxidation products of phospholipids including PC are known to have significant adverse biological effects [30–32]. Phopholipid hydro peroxides, an oxidation product of PC, can form a covalently linked lipid–protein adducts, which may play a role in the development of oxidative injury and functional impairment of biological membranes [33]. On the other hand, several workers [34, 35] have attributed important nutritional role of lecithin in both animal and humans. Alcohol induced fibrosis and cirrhosis in both animals as well as human have been shown to be reduced and even reversed after lecithin administration [36, 37]. Lecithin has also been reported to produce cholesterol-lowering effects [38]. The lecithin administration has been suggested for the prevention and treatment of atherosclerosis [39]. It also reduces chemically induced hepatocarcinogenesis in rats and the growth of hepatic cancer cells [40]. These reports highlight the protective and non-toxic effects of lecithin.

The present study was carried out to explore the toxicity of oxidized PC due to its fast autooxidation [41], the protective and non-toxic effects of lecithin and its wide application in food industry.

The oxidized PC used in this study contain about 13% linoleic acid (18:2 ∆9, 12cis) in addition to palmitic 34.2% (16:0), stearic 18.3% (18:0), oleic (13.1%) (18:1 Δ9 cis) and docosahexaenoic 2.2% (22:6) acids along with a moderately high amount of hydroperoxides and their degradation products, as apparent from its high TBARS (1200 mg/kg).

In earlier study [7] a decrease in body weight and food consumption was observed in rats fed diet containing autoxidized vegetable oils. This effect could be attributed to the oxidized oil added to the diet which caused taste and odor deterioration. However, in the present study when oxidized PC was given orally to the rats, a gradual increase in food consumption and body weight of animals in each group was observed. The slight gain in the body weight of the animals receiving oxidized PC corresponds to the general effect of phospholipids as growth promoter [41]. In the present study, there was no significant difference in the weight of different organs of treated and untreated rats. Several authors reported the hypolipidemic effect of PC in rats and humans [38, 39, 41–43]. The current study indicated that the rats treated with oxidized PC for 2 weeks (Group II) showed a significant increase in plasma cholesterol (P < 0.05) and TG (P < 0.01) content. However, this difference was not observed in rats treated for 4 weeks (Group IV). Cholesterol and TG content of liver, heart and kidney were not affected in both treated and control rats.

It has been reported that the administration of oxidized oils to animals generally increase the TBARS of several organs and results in serious tissue damage [1, 26]. Our results also demonstrated the increase in TBARS substances in thymus, spleen, heart, kidney, liver and lungs of rats receiving oxidized PC. The accumulation of TBARS displayed an increasing trend over 4 weeks (Group IV) in kidney, liver and lungs while in case of heart, thymus and spleen a decline was observed after 4 weeks (Group IV) treatment. The reason for this decline in TBARS value of heart, thymus and spleen of Group IV is not certain. It may be partly due to the possible reaction of the secondary aldehydic oxidation products with protein, as reported by Gonzales et al. [44]. We found that the overall oxidative stress in the tissues were significantly higher after oxidized PC treatment, however, the effect varied considerably from tissue to tissue. The oxidative stress was much more pronounced in spleen and heart after a short treatment (Group II, 2 weeks), while kidney and liver were more stressed after prolonged treatment (Group IV, 4 weeks). The red cell membrane has been used as a model for oxidative damage to biomembranes as well as an index of vitamin E status [5]. Hemolysis is also a typical type of membrane damage induced by various lipids. Rats fed oxidized PC showed elevated hemolysis in Group II (2 weeks), while rats treated for 4 weeks (Group IV) did not show a significant increase in hemolysis as compared to its respective control. This may be partly due to more depletion of antioxidant defense system in the initial stages of oxidative stress. While during prolonged treatment the animals seem to adjust slightly to the oxidative stress caused by feeding reactive lipid oxidation products. The metabolic responses in terms of this adjustment to oxidative stress remain to be elucidated. Precise reason for this inconsistency needs further investigation.

It has been reported that immune system is particularly sensitive to oxidant mediated injury [38]. Lipid peroxidation caused by cumene hydroperoxide (in vitro) induces a functional deterioration in spleenocytes [3], while Oreda et al. [28] demonstrated a significant damage in the thymus of mice by the oral intake of methyl linoleate hydroperoxide (MLHPO). The toxic effect of cumene hydroperoxide (in vitro) and MLHPO (in vivo) has been reported to show a depression of lymphocyte function. In the present study, the oxidized PC caused oxidative stress not only in liver, heart, kidney, and lung but it also caused an increase in TBARS of thymus and spleen that led to conclude that an uptake of oxidized PC may gradually lead to the compromise of immune response.

References

- 1.Esterbauer H. Cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of lipid peroxidation products. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993;57:779S–786S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/57.5.779S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohn JS. Oxidized fat in the diet, postprandial lipaemia and cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2002;13:9–24. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200202000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shimura J, Shimura F, Hosoya N. Functional disability of rats spleenocytes provoked to lipid peroxidation by cumene hydroperoxide. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1985;845:43–47. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(85)90052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee JYC, Wan JMF. Vitamin E supplementation improves cell- mediated immunity and oxidative stress in Asian men and women. J Nutr. 2000;130:2932–2937. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.12.2932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoshida H, Kajimoto G. Effect of dietary vitamin E on the toxicity of autoxidized oil to rats. Ann Nutr Metab. 1989;33:153–161. doi: 10.1159/000177532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kimura T, Lida K, Takei Y. Mechanisms of adverse effects of air-oxidized soy bean oil-feeding in rats. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol. 1984;30:125–133. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.30.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishioka T, Havinga R, Tazuma S, Stellaard F, Kuipers F, Verkade HJ. Administration of phosphatidyl choline–cholesterol liposomes partially reconstitutes fat absorption in chronically bile diverted rats. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1636:90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weihrauch JL, Son YS. The phospholipids content of foods. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1983;60:1971–1977. doi: 10.1007/BF02669968. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoon TH, Kim IH. Phosphatidylcholine isolation from egg yolk phospholipids by high performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr A. 2002;949:209–216. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9673(01)01270-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qin J, Goswami R, Balabanov R, Dawson G. Oxidized phosphatidylcholine is a marker for neuroinflammation in multiple sclerosis brain. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:977–984. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kono N, Inoue T, Yoshida Y, Sato H, Matsusue T, Itabe H, Niki E, Aoki J, Arai H. Protection against oxidative stress induced hepatic injury by intracellular type II platelet activating factor acetylhydrolase by metabolism of oxidized phospholipids in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:1628–1636. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708622200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoshimi N, Ikura Y, Sugama Y, Kayo S, Ohsawa M, Yamamoto S, Inoue Y, Hirata K, Itabe H, Yoshikawa J, Ueda M. Oxidized phosphatidylecholine in alveolar macrophages in idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Lung. 2005;183:109–121. doi: 10.1007/s00408-004-2525-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patrick T, David G. Use of phosphatidylcholine for the correction of lower lid bulging due to prominent fat pads. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2006;8:129–132. doi: 10.1080/14764170600891756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Igene JO, Pearson AM. Role of phospholipids and triglycerides in warmed-over flavor development in meat model systems. J Food Sci. 1979;44:1285–1290. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1979.tb06420.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khayat A, Schwall D. Lipid oxidation in sea food. Food Technol. 1983;37:130–140. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melton SL. Methodology of following lipid oxidation in muscle foods. Food Technol. 1983;37:105–111. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sessa DJ, Warner K, Honig DH. Soybean phosphatidylcholine develops bitter taste on autoxidation. J Food Sci. 1974;39:69–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1974.tb00990.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.David J, Canty MS, Zeisel SH. Lecithin choline in human health and disease. Nutr Rev. 1994;52:327–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1994.tb01357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shu-Ying Chung, Moriyama T, Uezu E, Uezu K, Hirata R, Yohena N, Mosuda Y, Kokubu T, Yamamoto S. Administration of phosphatidylcholine increases brain acetylcholine concentration and improves memory in mice with dementia. J Nutr. 1995;125:1484–1489. doi: 10.1093/jn/125.6.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Navder KP, Lieber CS. Polyenylphosphatidylcholine on ethanol-induced mitochondrial injury in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;291:1109–1112. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen R, Yang L, McIntyre MT. Cytotoxic phospholipids oxidation products: cell death from mitochondrial damage and the intrinsic caspase cascade. J Biol Chem. 2007;10:1074. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702865200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshida H, Hirooka N, Kajimoto G. Microwave energy effects on quality of some seed oils. J Food Sci. 1990;55:1412–1416. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1990.tb03947.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahmad F, Schiller H, Mukherjee KD. Lipid containing isoricinoleoyl (9-hydroxy-cis-12-octadecenoyl) moieties in seeds of Wrightia species. Lipid. 1986;21:486–490. doi: 10.1007/BF02535633. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Draper HH, Csallany AS. A simplified hemolysis test for vitamin E deficiency. J Nutr. 1969;98:390–394. doi: 10.1093/jn/98.4.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buckingham KM. Effect of dietary polyunsaturated/saturated fatty acids ratio and dietary vitamin E on lipid peroxidation in rats. J Nutr. 1985;115:1425–1435. doi: 10.1093/jn/115.11.1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uchiyama M, Mishara M. Determination of malonaldehyde precursor in tissues by thiobarbituric acid test. Anal Biochem. 1978;86:271–278. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(78)90342-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Folch J, Lees M, Sloane Stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipids from animal tissues. J Biol Chem. 1957;226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orada M, Ito E, Terao K, Miyawaza T, Fujimoto K, Kaneda T. The effect of dietary lipid hydroperoxide on lymphoid tissues in mice. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;960:229–235. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(88)90068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ichinose T, Nobuyuki S, Takano H, Abe M, Sadakane K, Yanagisawa R, Ochi H, Fujioka K, Lee KG, Shibamoto T. Liver carcinogenesis and formation of 8- hydroxyl-deoxyguanosine in C3H/He N mice by oxidized dietary oils containing carcinogenic dicarbonyl compounds. Food Chem Toxicol. 2004;42:1795–1800. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zimmerman GA, Prescott SM, Mclntyre TM. Oxidatively fragmented phospholipids are inflammatory mediators: the dark side of polyunsaturated lipids. J Nutr. 1995;125:1661S–1665S. doi: 10.1093/jn/125.suppl_6.1661S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smiley PL, Stremler KE, Prescott SM, Zimmerman GA, Mclntyre TM. Oxidatively fragmented phosphatidylcholines activate human neutrophils through the receptor for platelet activating factor. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:1104–1110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hayashi T, Uchida K, Takebc G, Takahashi K. Rapid formation of 4-hydroxyl-2-noneal, malondialdehyde and phosphatidylcholine aldehyde from phospholipids hydroperoxide by hemoproteins. Free Radical Biol Med. 2004;36:1025–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parinandi NL, Weis BK, Natrajan V, Heerald HOS. Peroxidative modification of phospholipids in myocardial membranes. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1990;280:45–52. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(90)90516-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zeisel SH. Lecithin in health and human nutrition. In: Szuhaj BF, editor. Lecithin: sources, manufacture and uses. Champaign, IL: American Oil Chemical Society; 1989. pp. 225–236. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gunther KD. Lecithin an active substance in animal nutrition. Kraftfutter. 1994;6:213–219. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lieber CS, DeCarli LM, Mak KM, Kim CL, Leo MA. Attenuation of alcohol induced hepatic fibrosis by polyunsaturated lecithin. Hepatology. 1990;12:1390–1398. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840120621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leiber CS, Robins SJ, Li J, et al. Phosphatidylcholine protects against fibrosis and cirrhosis in baboon. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:152–159. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(94)95023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiang Y, Noh SK, Koo SI. Egg phopatidylcholine decreases the lymphatic absorption of cholesterol in rats. J Nutr. 2001;131:2358–2363. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.9.2358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wojcicki J, Pawlick A, Samochowiec L, Kaldonska M, Mysliwiec Z. Clinical evaluation of lecithin as a lipid-lowering agent. Phytother Res. 1995;9:597–599. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2650090814. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sakakima Y, Hayakawa A, Nakao A. Phosphatidyl induces growth inhibitors of hepatic cancer by apoptosis via death ligands. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56:481–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoshida Y, Ito N, Shimakawa S, Niki E. Susceptibility of plasma lipids to peroxidation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;305:747–753. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(03)00813-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watkins TR. Role of soya phospholipid fractions in the bioavailability of dietary lipids. In: Paltaut H, Lekin D, editors. Lecithin and health care. Germany: Semmelweis-Verlag; 1985. pp. 146–157. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mastellone I, Polichetti E, Gres S, Maisonnleuve C, Domingo N, Mann V, Lorec AM, Farnarier C, Portugal H, et al. Soybean phosphatidylcholines lower lipidemia: mechanisms at the levels of intestine, endothelial cell, and hepato-biliary axis. J Nutr Biochem. 2000;11:461–466. doi: 10.1016/S0955-2863(00)00115-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gonzales MJ, Gray JI, Schemmel RA, Dugan L, Jr, Welsch CW. Lipid peroxidation products are elevated in fish oil diets even in the presence of added antioxidants. J Nutr. 1992;122:2190–2195. doi: 10.1093/jn/122.11.2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]