Abstract

Objective

To compare temporal trends in the incidence and mortality of renal cell cancer among blacks and whites for clues to etiologic differences.

Methods

We examined trends in age-adjusted and age-specific SEER incidence and US mortality rates for renal cancer for 1973 through 2007, as well as nephrectomy rates from surgery codes for kidney cancer for 2000 through 2007.

Results

For nearly four decades, incidence rates for renal cell cancer have been rising more rapidly among blacks than whites, leading to a shift in excess from among whites to among blacks, almost entirely accounted for by an excess of localized disease. The incidence patterns are puzzling, since localized renal cell cancer is primarily detected incidentally by imaging, to which blacks have historically had less access. In contrast to the incidence patterns, there has been an unexpected convergence of renal cancer mortality rates, which have been virtually identical among blacks and whites since the early 1990s. Nephrectomy rates, regardless of stage, were lower among blacks than among whites, despite almost identical cause-specific survival rates in both races.

Conclusions

The identical mortality patterns, combined with higher and more rapidly increasing incidence and lower rates of nephrectomies among blacks, suggest that renal cell cancer may tend to be a less aggressive tumor in blacks. This hypothesis is supported by the favorable stage distribution among blacks and their higher survival for distant and unstaged cancer. Further research into the enigmatic descriptive epidemiology and the biology and natural history of renal cell cancer may shed light on the etiology of this malignancy and its more frequent occurrence among black Americans.

Keywords: renal cell cancer, incidence, mortality, nephrectomy, racial differences

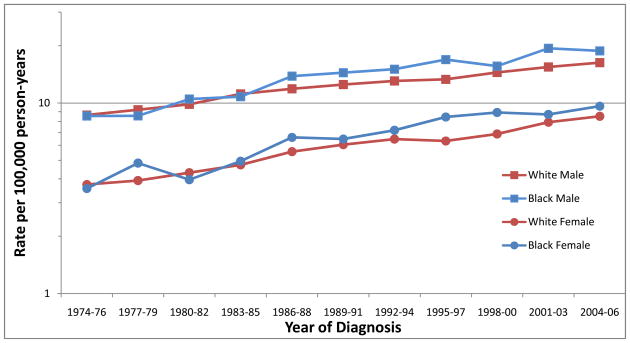

Incidence rates for renal cell cancer have been rising by nearly 2% per year in the United States since the 1970s [1, 2]. Perhaps the most salient feature of these incidence trends has been the more rapid increase among blacks than whites, leading to a pronounced shift in excess from among whites to among blacks beginning as far back as the mid-1980s (Figure 1) [3]. By 2002–2007, the age-adjusted incidence rates of renal cell cancer among black men, white men, black women, and white women were 20.0, 17.4, 9.6 and 8.8 per 100,000 person-years, respectively [4].

Figure 1.

Trends in age-adjusted (2000 United States standard) incidence of renal cell cancer by race and sex, 1974–2006 (Based on SEER data for nine geographic regions of the United States: Atlanta, Georgia; Connecticut; Detroit, Michigan; Hawaii; Iowa; New Mexico; San Francisco/Oakland, California; Seattle/Puget Sound, Washington; and Utah) [4].

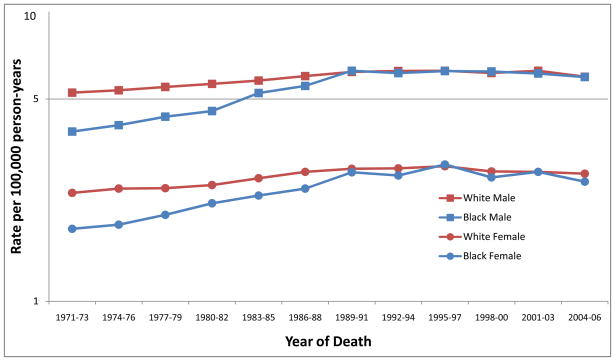

In contrast to the incidence trends, there has been a convergence over the past four decades of national kidney cancer mortality rates, with rates becoming more or less identical among blacks and whites for both men and women since the early 1990s (Figure 2). Such similarity in mortality rates is unexpected and has not been observed, to our knowledge, for any other type of cancer which exhibits a strong black excess in incidence. While mortality data do not permit the separation of renal cell from other forms of kidney cancer, renal cell cancers account for approximately 85% of kidney cancers, and little difference in survival by cell type has been reported [5], so that the kidney cancer mortality trends primarily reflect patterns related to renal cell cancer.

Figure 2.

Trends in age-adjusted (2000 United States standard) mortality from kidney cancer by race and sex, 1971–2006 (Based on National Center for Health Statistics data for the entire United States) [4].

The higher incidence of renal cell cancer among blacks is almost entirely accounted for by an excess of localized disease. During 2000–2007, the incidence rate of localized renal cell cancer was 13.2 per 100,000 person-years among black men, compared with 10.8 among white men (Table 1); corresponding figures among black and white women were 6.9 and 6.0, respectively. When examined by age and sex, the excess of localized renal cell cancer among blacks is evident among both younger and older patients and is more pronounced among men than women. For regional and distant renal cell cancer, incidence rates were similar between blacks and whites, with, if anything, slight deficits among black men and women, particularly over the age of 60 years.

Table 1.

Renal cell cancer incidence rates1, rates of nephrectomy, and cause-specific survival2, according to race and stage of renal cell cancer; SEER Program 2000–2007

| All ages | Age <60 years | Age >60 years | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence | Nephrectomy | Cause-specific survival | Incidence | Nephrectomy | Cause-specific survival | Incidence | Nephrectomy | Cause-specific survival | |

| White male | |||||||||

| Local | 10.8 | 89.1 | 93.2 | 4.6 | 94.8 | 95.4 | 39.4 | 85.1 | 91.0 |

| Regional | 2.9 | 93.2 | 68.6 | 1.0 | 96.7 | 71.3 | 12.3 | 91.4 | 66.8 |

| Distant | 3.0 | 38.6 | 12.1 | 1.1 | 53.6 | 14.6 | 12.8 | 30.6 | 10.4 |

| Unstaged | 0.7 | 16.6 | 47.4 | 0.1 | 37.4 | 69.1 | 3.7 | 11.6 | 40.0 |

| Black male | |||||||||

| Local | 13.2 | 87.0 | 93.7 | 6.0 | 90.9 | 95.1 | 47.0 | 82.9 | 91.6 |

| Regional | 2.4 | 89.7 | 62.5 | 0.9 | 93.4 | 59.6 | 9.9 | 60.2 | 66.4 |

| Distant | 3.3 | 29.5 | 12.6 | 1.5 | 35.7 | 9.0 | 12.6 | 11.7 | 17.0 |

| Unstaged | 1.1 | 11.1 | 55.0 | 0.2 | 23.6 | 68.3 | 5.6 | 6.3 | 49.0 |

| White female | |||||||||

| Local | 6.0 | 89.5 | 93.8 | 2.8 | 95.9 | 96.9 | 20.1 | 85.1 | 91.3 |

| Regional | 1.2 | 89.6 | 65.1 | 0.4 | 95.9 | 71.3 | 4.8 | 87.0 | 61.8 |

| Distant | 1.3 | 32.2 | 8.5 | 0.4 | 52.5 | 12.4 | 5.6 | 25.3 | 6.9 |

| Unstaged | 0.3 | 11.4 | 41.1 | 0.1 | 39.6 | 79.3 | 1.8 | 7.0 | 32.4 |

| Black female | |||||||||

| Local | 6.9 | 85.9 | 93.8 | 3.0 | 93.2 | 96.1 | 24.5 | 79.8 | 91.3 |

| Regional | 0.9 | 82.0 | 59.8 | 0.4 | 93.1 | 69.2 | 4.3 | 75.8 | 52.4 |

| Distant | 1.4 | 27.3 | 12.0 | 0.6 | 40.5 | 11.5 | 5.5 | 18.2 | 12.9 |

| Unstaged | 0.4 | 9.8 | 49.9 | 0.1 | 26.7 | 47.7 | 2.0 | 3.7 | 49.8 |

Rates per 100,000 person-years, age-adjusted using the 2000 United States standard population.

Percentage of cases surviving 5 years after diagnosis of a first primary renal cell carcinoma.

The higher incidence of localized disease among blacks occurred as early as the 1970s; for the periods 1973–77, 1978–82 and 1983–87, the incidence rates (per 100,000) for localized renal cell cancer were 3.7, 4.7 and 6.1 for black men, 3.5, 3.9, and 5.0 for white men, 1.8, 2.2 and 2.8 for black women, and 1.7, 1.8 and 2.3 for white women, respectively. Localized renal cell cancer has also been increasing at a significantly faster pace among blacks of all ages than among whites since the 1970s [6]. These incidence patterns are puzzling and unexpected, particularly since early stage, localized renal cell cancer is generally asymptomatic and primarily detected incidentally by imaging modalities such as computed tomography or ultrasonography, which have been shown to be utilized less frequently by blacks than whites [6, 7].

For early stage, localized renal cell cancer, cause-specific survival rates (which represent the probability of a kidney cancer case dying with kidney cancer as the cause of death) are high (>90%) and virtually identical among blacks and whites (Table 1), regardless of age or sex, so that most kidney cancer deaths occur among patients with regional or distant disease. For regional or distant disease, cause-specific survival is also generally comparable between blacks and whites (Table 1). To determine if higher stage-specific rates of nephrectomies, the only effective treatment for renal cell cancer, among blacks may help explain the equivalent mortality rates among blacks and whites, we examined surgery codes for kidney cancer in the SEER 17 Registries from 2000–2007. As shown in Table 1, rates of nephrectomy are in fact slightly lower among blacks than among whites with localized renal cell cancer, despite the virtually identical cause-specific survival. For distant disease, which accounts for a small fraction of the renal cell cancer incidence excess in younger blacks, the disparity in nephrectomy rates by race is even larger, with blacks undergoing such surgery much less frequently, while cause-specific survival for distant disease is paradoxically higher among blacks, particularly among those over age 60 years. For unstaged renal cell cancer, blacks have substantially lower nephrectomy rates, but comparable or higher survival rates, compared with whites. Zini et al. [8] have also reported similar survival despite lower nephrectomy rates among blacks, although others have reported lower survival rates among blacks compared with whites with renal cell cancer [9, 10].

A close examination of incidence and mortality trends for renal cancer by race over the past forty years reveals a pattern of higher and more rapidly increasing incidence among blacks compared with whites, which is not reflected in the virtually identical mortality rates of whites and blacks over the same time period This equivalence in mortality despite higher incidence does not appear to be a result of higher rates of nephrectomies among blacks; nor is there any obvious explanation for the almost 30% higher incidence of localized disease among blacks. The possibility that the biology or natural history of renal cell cancer may differ among blacks and whites, particularly its aggressiveness, is suggested by the favorable stage distribution among blacks and their higher survival for distant and unstaged cancer. Moreover, rates of end stage renal disease, in particular hypertension-related end stage renal disease, are at least four-fold higher among blacks than among whites, and 20 times higher among young black males [11]. Among blacks, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and hypertension-attributed end-stage kidney disease are strongly associated with variants in the APOL1 gene on chromosome 22 [12]. The variants are common in African-Americans and absent in European-Americans, supporting a genetic basis for racial heterogeneity in susceptibility to, and possibly other aspects of, kidney disease (12).

Further research into the enigmatic descriptive epidemiology and natural history of renal cell cancer may point to clues in the etiology of this malignancy and its more common occurrence among black Americans which has persisted for several decades.

Acknowledgments

Funded in part by The Southern Community Cohort Study (SCCS) grant R01CA092447 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI).

References

- 1.Jemal A, Thun MJ, Ries LAG, Howe HL, Weir HK, Ceter MM, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2005, featuring trends in lung cancer, tobacco use, and tobacco control. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1672–1694. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathew A, Devesa SS, Fraumeni JF, Jr, Chow WH. Global increases in kidney cancer incidence, 1973–1992. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2002;11:171–178. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200204000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kosary CL, McLaughlin JK. Kidney and renal pelvis. In: Miller BA, Ries LAG, Hankey BF, Kosary CL, Harras A, Devesa SS, Edwards BK, editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review: 1973–1990. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 1993. Department of Health and Human Services publication NIH 93–2789, Xl-X22. [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Cancer Institute. DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Cancer Statistics Branch. SEER Program 17 Registries Public Use Tapes (1973–2007, varying), November 2008 Submission, Released April 2009.

- 5.Lipworth L, Tarone RE, McLaughlin JK. The epidemiology of renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2006;176:2353–2358. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.07.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vaishampayan N, Do H, Hussain M, Schwartz K. Racial disparity in incidence patterns and outcome of kidney cancer. Urol. 2003;62:1012–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2003.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geronimus AT, Bound J, Waidmann TA, Hillemeier MM, Burns PB. Excess mortality among blacks and whites in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1552–1558. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199611213352102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zini L, Perrotte P, Capitanio U, Jeldres C, Duclos A, Arjane P, et al. Race affects access to nephrectomy but not survival in renal cell carcinoma. BJU Int. 2008;103:889–893. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berndt SI, Carter HB, Schoenberg MP, Newschaffer CJ. Disparities in treatment and outcome for renal cell cancer among older black and white patients. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3589–3595. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stafford HS, Saltzstein SL, Shimasaki S, Sanders C, Downs TM, Sadler GR. Racial/ethnic and gender disparities in renal cell carcinoma incidence and survival. J Urol. 2008;179:1704–1708. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Renal Data System, USRDS 2009 Annual Data Report. Atlas of end-stage renal disease in the United States. Bethesda, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2009. Available at: http://www.usrds.org/atlas.htm.

- 12.Genovese G, Friedman DJ, Ross MD, Lecordier L, Uzureau P, Freedman BI, Bowden DW, Langefeld CD, Oleksyk TK, Knob AU, Bernhardy AJ, Hicks PJ, Nelson GW, Vanhollebeke B, Winkler CA, Kopp JB, Pays E, Pollak MR. Association of trypanolytic ApoL1 variants with kidney disease in African-Americans. Science. 2010;329:841–845. doi: 10.1126/science.1193032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]