‘Tell me and I forget. Show me and I remember. Involve me and I understand.”

-Chinese Proverb

Expanding the capacity for clinical care and health research is a global priority and a global challenge. In disenfranchised communities facing the largest burden of disease, whether they be in rural Africa or in urban US, there is a great need for more well-trained, competent and dedicated health care providers. In addition, globalization has necessitated that an understanding of global health issues is a requirement for all health care providers, whether they be community health workers in rural Uganda, private practitioners in Mumbai or Los Angeles or faculty at Johns Hopkins Medical School. Resource-limited communities also require a greater capacity for and ownership of their own health research priorities and programs. Meeting these pressing needs for human capacity building in health care and research will require additional resources, but also innovation. Traditional approaches to clinical and research education are important and necessary, but not sufficient to achieve the scale and pace of human capacity building required. Distance learning programs, that include mHealth as well as other information technology (IT) platforms and tools, can provide unique, timely, cost-effective and valuable opportunities to expand access to training, clinical care support and strategic information for clinicians and researchers, throughout the world.

Advances and investments in IT are providing many new tools for delivering and accessing information, as well as for learning. These tools and new IT infrastructure are rapidly becoming available in developing countries and resource-limited communities around the world, providing new opportunities for clinical and research capacity building initiatives. Effective distance learning programs develop and utilize multiple tools in the IT toolbox, to optimize their capacity building and teaching. In addition to providing optimal content to address the learning objectives of specific training programs, it is also important to strategically choose the optimal tools to deliver and access this content, as well as to recognize the limitations of distance learning and to rigorously evaluate the impact of any training program. These steps are essential before major investments of resources and time required for the scale-up and large- scale implementation of distance education programs to expand global health manpower and capacity.

The Johns Hopkins Center for Clinical Global Health Education (CCGHE) was established in 2005 to provide access to high quality training to health care providers in resource-limited settings. The CCGHE made a strategic decision to develop, utilize and evaluate distance learning platforms to achieve our mission. The initial years of this new program have led to a number of lessons learned that may be helpful to other programs considering the use of distance learning programs, to expand global health clinical and research capacity.

What is Distance Learning?

As mentioned previously, distance learning involves the strategic use of multiple IT tools to teach and to learn. Distance learning programs also typically utilize IT tools to evaluate the impact of their programs. The distance learning toolbox includes multiple platforms to interact with, access and deploy information, that may be important for clinicians and researchers. In some cases, the most effective training content can be text or image-based. Audio, video and interactive formats, including simulation platforms can also be utilized. Multimedia content and large amounts of data can be shared in very portable formats, including DVD’s, CDroms, compact data discs, thumb drives, etc. Websites, portals and local area networks can also store and deploy multimedia content. Availability of reliable fiber or wireless networks can support use of email, web-streaming, video conferencing, chat rooms, social networks, cell phones, smart devices and other interactive platforms to facilitate training. These formats can be used for live group-learning experiences, often referred to as synchronous learning formats. In many cases asynchronous platforms, including email, on-line forums and social networking sites, can be very efficient and effective methods to facilitate faculty-student interactions and group learning. Many of these tools are well known and used in developed countries, where distance learning is more widely established. The CCGHE has utilized multiple tools in this toolbox, as well as developed new tools and approaches to optimize our mission to support health care providers in very remote communities.

Providers in Resource-Limited Settings Use the Web to Learn

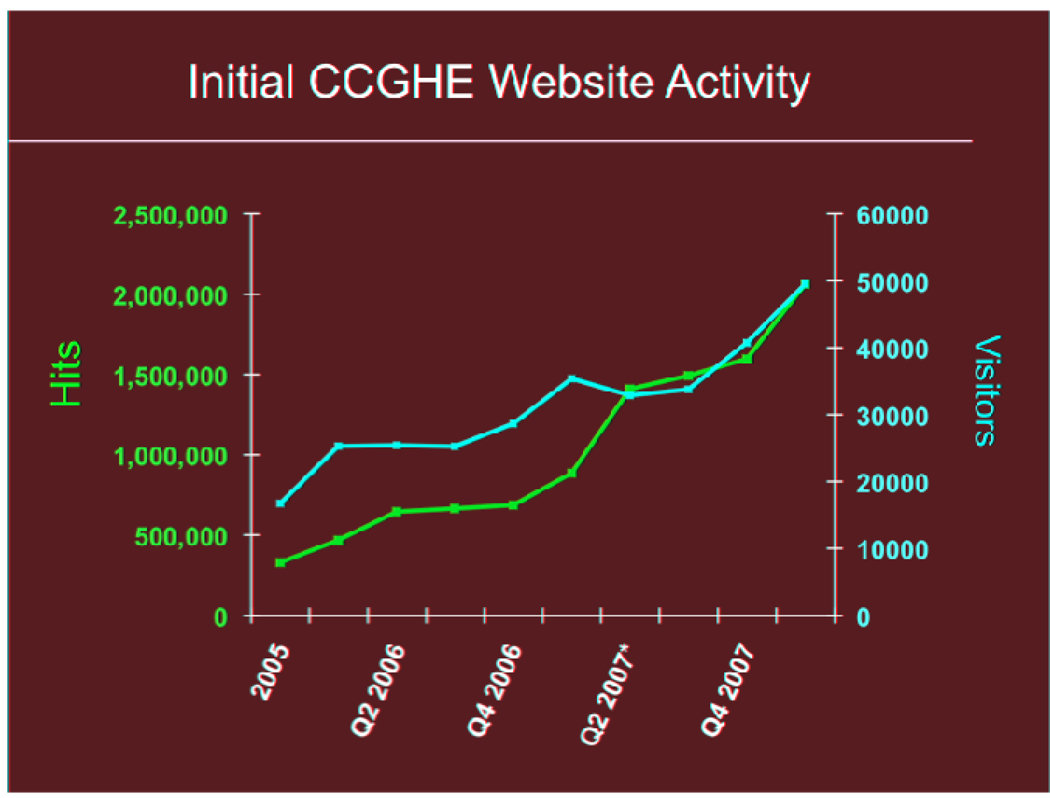

When the CCGHE was launched, one of the first distance learning tools developed and utilized was a simple website, where content specifically relevant to providers in resource-limited settings was made available1. Initially, these were simply text, pdf files or web links of key best practices and guidelines from governments and organizations such as the CDC, WHO, UNAIDS, IAS, etc. In addition, links to live and recorded webcasts of weekly Infectious Diseases Grand Rounds from Johns Hopkins were made available. Within a matter of months, the number of visits to this website quickly rose to more than 500,000 hits/month from more than 100 different countries, including many countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America (Figure 1). This rapid demonstration of interest and demand for clinical training content was a particular surprise, given that this demand was generated without any significant public advertisement or effort by the CCGHE to announce the launch of our website or program. In addition to the demonstration that providers from resource-limited communities in Africa, Asia and Latin America use the web to learn, our early experience with the CCGHE website demonstrated the power of the web to rapidly share information around the world.

Figure 1.

Initial CCGHE Website Activity

Distance Learning is Feasible and Cost-effective for Resource-Limited Settings

One of the first CCGHE initiatives to develop a full distance-learning course was for HIV providers in Zambia. There are a number of learning management systems (LMS) available to develop and deploy distance learning courses. From its inception, the CCGHE has made a strategic decision to utilize less-expensive, open-source tools for our training programs, whenever possible. Therefore, our first distance learning course utilized the open-source LMS program called Moodle2. The HIV Clinical Care Course for Zambia consisted of 21 recorded lectures by Hopkins and Zambian experts, that were formatted into 5 modules, made available on the web and on CDrom, for participants without reliable web access. The course was delivered over a 6-week period and included a weekly live faculty web chat and on-line discussion forum. Course learning objectives were re-enforced through case discussions, as well as questions/answer (Q&A) sessions with faculty. To our knowledge, this was the first distance-learning course ever offered in Zambia. Despite great efforts by collaborating organizations in Zambia, it was initially very difficult to engage students willing to participate in this first course. Reasons for this reluctance to participate in a distance learning course included a healthy skepticism about the reliability of internet access in Zambia, required for the low-bandwidth live faculty chats, course registration and knowledge testing. In addition, there was uncertainty about the benefit of participating in a distance-learning course related to HIV clinical care, as well as a concern that providers in Zambia would not participate in a free training course that did not also incentivize them with payment for their participation.

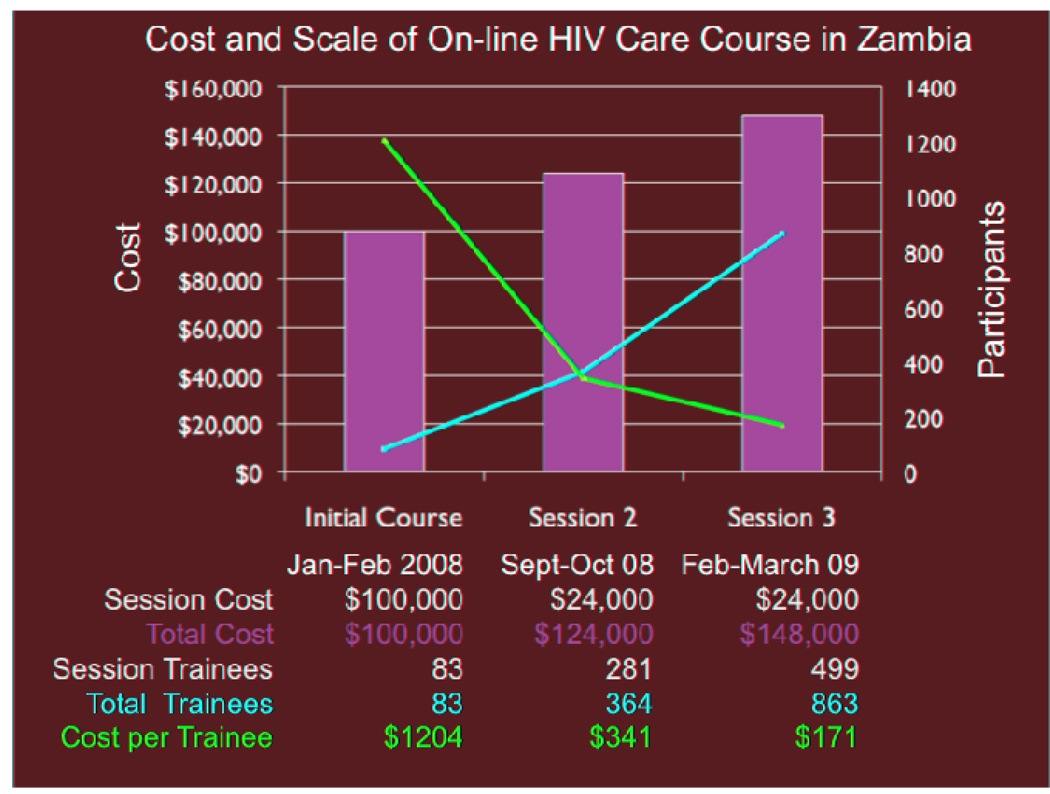

Despite a challenging initial launch, the course was successfully deployed and included the live synchronized chats. The value and feasibility of a distance learning course format, even in a setting like Zambia with very limited internet connectivity, was evidenced by the great demand for this course, as well as by the successful on-line participation of Zambian clinicians. A particularly notable demonstration of feasibility was the success of one live on-line session lead by a Hopkins faculty member from Dhaka, Bangladesh to course participants in Zambia. Within one month of completion of the first HIV care course with 83 registered participants, Zambian colleagues requested that the course be redeployed and more than 281 students registered for the second session of this course. An additional 499 students registered for the third session of this course. In addition to demonstrating to the CCGHE and to our partners in Zambia that distance learning is a feasible and valued training format for clinicians in resource-limited settings, this Zambian course also demonstrated the cost-effectiveness of a distance-learning format.

As shown in Figure 2, the initial cost of recording and developing this course for the first 83 registered students was $1204/student. Since recurring costs for the second and third sessions of this course were much less, the cost per student was ultimately reduced to $171/student. Therefore, the per student cost of conducting a 6-week, 21 lecture distance learning course delivered to ~900 Zambian clinicians, by Zambian and US faculty experts was significantly less than comparable HIV training courses offered in Zambia3. In addition, the distance learning format permitted a more flexible schedule for students, who were able to participate in this course without interrupting their normal work schedule. While the feedback from the course evaluation completed by Zambian participants was extremely positive and significant knowledge gains were demonstrated through knowledge test scores, there was no opportunity to compare the impact of this on-line course with the impact of other more standard training formats. This early experience highlighted the need for resources and opportunity to properly evaluate any training program, particularly those using new distance education technology.

Figure 2.

Cost and Scale of On-line HIV Care Course in Zambia

Distance Learning is Empowering and Facilitates South-South Capacity Building

One of the most successful and most sustainable CCGHE programs was initiated in 2006, in collaboration with colleagues at the Addis Ababa University (AAU) in Ethiopia. The format for this program began as live video-conference supported presentations and discussions of clinical cases of patients with HIV infection, by faculty and students from AAU, Hopkins, Mayo Clinic and University of South Carolina. The initiation of this program was also made possible through the support of a number of other sponsors and stakeholders, including PEPFAR and the World Bank Global Development Learning Network (GDLN), who provided access to their video conferencing facility in Addis Ababa to launch this program. Again, this was the first time this type of distance learning format had been undertaken in Ethiopia and, not surprisingly, there was considerable early skepticism about its feasibility, value and sustainability. In the early phase of this program, 20–30 busy faculty were expected to drive a long distance every other Friday afternoon, from AAU to the Civil Service College in Addis Ababa, the location of the GDLN facility, in order to participate in this program. At each session, 2–3 clinical cases are presented and discussed by the participating faculty. These case discussions were recorded and made available through live and archived webcasts, as well as burned on CDroms and shipped to Ethiopia for distribution around the country to providers without reliable internet or access to the video conferencing facility.

The early case discussions were notable for the US faculty providing much of the discussion and input. However, within a very short period of time, our colleagues in Ethiopia took ownership and leadership of this program. Now, 4 years after a skeptical and difficult start to the program, there have been more than 200 case discussions recorded and distributed throughout Ethiopia and clinicians throughout the world have benefited by viewing these excellent discussions on line. The program was such a success that the AAU has now built it’s own state-of-the-art video conferencing facility in their medical school auditorium, expanding participation to many more faculty and students. In addition, two more Ethiopian medical schools have build similar facilities and are now actively participating in these case conferences, which continue to be broad cast throughout the world. The recent global availability of the infrastructure for video conferencing is a tremendous opportunity to initiate similar programs and is a particularly valuable platform for learning in the context of clinical case discussions, clinical consultations and group learning4. The success of the CCGHE program in Ethiopia has led directly to the recent initiation of similar video conference clinical education programs in other countries including in India and Palestine 5,6,7.

Another demonstration of the value of distance learning to support south-south collaboration is a recent CCGHE course focused on diagnosis, treatment and prevention of tuberculosis. This was an in-depth, comprehensive 6-week modular course, with 25 prerecorded lectures and live video conference-supported activities that engaged faculty from the US and South Africa, as well as faculty and 235 students in India and Pakistan in a vibrant and interactive learning experience that resulted in well-documented improvements in knowledge for the students. This course, supported by the Fogarty International Training Program, deployed the 25 lectures and other course materials on CDroms. Students completed online pre- and post-course knowledge assessments, as well as course evaluations. In addition, 11 live videoconference discussion sessions were scheduled linking faculty and students at BJ Medical College and National AIDS Research Institute in India, Indus Hospital in Pakistan, and Johns Hopkins in Baltimore. To accommodate participants unable to participate in the videoconferences, an internet link was established to view the live webcast, with the ability to ask questions. Additionally, an asynchronous Q&A discussion forum was available on the course website, where participants post questions at any time for the faculty and fellow participants. Faculty monitored the forum and responded to questions posted within 36–72 hours. Additionally, links to the recorded videoconference sessions were posted in both low and high bandwidth format and accessible to participants from the website. The median correct score for the pre-tests was 66%, compared to 86% for the post-test and 95% of students completing the post-test received a score of >70%, which was our cut-off for certification of competence with the material. Greater than 90% of the respondents to the course evaluation “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that the course objectives and expectations were clearly defined, that the course was organized in a way that facilitated learning, that the lectures were high quality and an appropriate length, that the content was applicable to their practice setting and that they would recommend the course to a colleague and would take a similar course again.

Distance Learning and mHealth Tools Can Support Task Shifting

A critical challenge to improvements in global health is the limited number of trained physicians, nurses and other health professionals. This health manpower gap is a well-recognized challenge and a number of public and private stakeholders have begun to address this need 8. As illustrated above, strategic use of distance learning tools can support these efforts to train high-level providers and to expand the capacity of health institutions. However, in most resource-limited settings, lower-level health care providers with limited access to professional training provide much of the health care in the communities. Providing access to training and clinical care support to these community health workers is also often challenged by rural and remote practice settings, as well as the financial and opportunity costs of traditional training programs that typically require providers to leave their practices and communities to receive training. Novel use of distance learning tools, particular wireless mHealth platforms, provide opportunities to scale–up health care capacity building initiatives and to address the training needs of community health workers and other providers in remote communities.

The development of a recent distance-learning adult male circumcision course in Uganda illustrates how distance learning can support scale-up of high-priority, specialized training. The Rakai Health Sciences Program (RHSP) is internationally known for their research demonstrating that adult male circumcision can reduce the risk of HIV acquisition9. This has led to large-scale programs to expand the training of medical personnel in this procedure10. The RHSP conducts an excellent circumcision training program for providers from around Africa. However, the impact of their program and other similar programs is limited by the time and expense required. For the RHSP course, to be certified a trainee typically travels to Rakai for two weeks, to participate in lectures, demonstrations and to perform an average of 20 supervised circumcisions11. To increase the efficiency, reduce the cost and increase the scale of the RHSP circumcision training program, the CCGHE created the Adult Male Circumcision Training eLearning Program, which was developed with the experts at the RHSP. This course provides instruction on the required steps to perform the Dorsal Slit surgery and all the necessary pre- and post-operative screening and care. Packaged for CDrom, this eLearning program and its knowledge assessment test can be used as both pre-training material and/or as a refresher and reference after hands-on training has occurred. The program is organized into five sections: 1) Preoperative considerations, 2) surgical preparations, 3) the dorsal-slit surgical procedure, 4) postoperative care, and 5) management of complications and includes 2 hours of lectures, high-definition video demonstrations and interactive exercises. The purpose of this eLearning course is to allow trainees to successfully complete course prior to coming to Rakai, where the expectation is that trainees will be better prepared for hands-on training and the time required to achieve certification could then be significantly less than the current 2 weeks. This would lead to improved efficiency, increased scale and cost reduction of the current RHSP circumcision training program. This example illustrates that distance learning tools are not a replacement for hands-on, bed-side or face to face training. Rather, these tools can be coordinated with more standard training platforms, to increase the overall capacity of existing training programs.

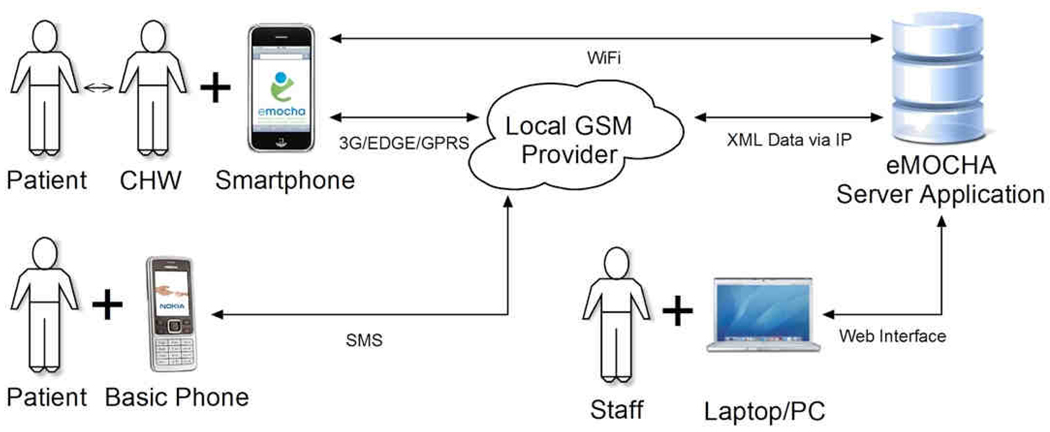

mHealth programs, taking advantage of the expanding wireless infrastructure in the world, are an increasingly important component of distance learning initiatives. mHealth interventions are particularly valuable for providing training and clinical care support to patients, lower level health workers and other providers, utilizing and delivering community-based and home care health services. In order to expand access to training to providers in rural African community settings, the CCGHE developed a secure, highly flexible and adaptable, open-source mHealth application, called the electronic Mobile Open-Source Comprehensive Health Application (eMOCHA). This application, which was selected as a Finalist for the 2010 Vodafone Wireless Innovation Award Program, is designed to leverage mobile phones to assist health programs, researchers, providers, and patients improve communication, education, patient care, and data collection.

eMOCHA synergizes the power of mobile technology, Android-supported devices, video and audio files, and a server-based application to analyze and GPS-map large amounts of data, implement interactive multimedia training, and streamline data collection and analyses. eMOCHA runs on all Android devices, smart phones and tablets, but also has the capacity to use regular cell phones to send and receive data through a web-based interface, utilizing toll- free SMS (Figure 3). eMOCHA projects are currently being deployed and evaluated in a wide-range of health care, public health and research programs in Uganda, Afghanistan and the US, with additional projects under development for Central America, India, Bangladesh and Ethiopia. These diverse projects include community and home based strategies to optimize HIV counseling and testing, HIV treatment adherence, TB diagnosis and treatment, malaria prevention and treatment, maternal and child health, reduction of IV drug use, management of chronic diseases, and prevention of domestic violence. mHealth platforms like eMOCHA can provide unique opportunities to empower health care providers, even in the most remote locations, with point-of-care, strategic training and clinical care support. The rapid growth and potential of mHealth programs to address global health priorities has led recently to new initiatives to support the development and evaluation of these innovative tools, including programs supported by the Gates Foundation Grand Challenges12, the Rockefeller Foundation13, the mHealth Alliance14, etc. However, as with most other uses of technology to improve health, there are limited data demonstrating that mHealth interventions improve health outcomes or clinical practice, particularly in resource-limited settings. The deployment of wireless devices and applications by health programs is rapidly expanding, despite the lack of good public health impact data to support their widespread deployment. The mHealth field appears to be following at “Ready, Fire, Aim” strategy, highlighting the urgent need for rigorous and well-designed evaluations of these initiatives.

Figure 3.

eMOCHA mHealth Application for Clinical Training and Care Support.

Distance Learning is Empowering and Facilitates South->North Global Health Capacity Building

In February 2010, a new global health course was offered for all first year Johns Hopkins medical students, that took advantage of new distance learning capacity to connect medical students in Baltimore with students and faculty in Uganda, Ethiopia, Pakistan and India. The purpose of this course was to introduce basic global health concepts to first year medical students. A lesson learned from this course was that distance learning can support unique educational experiences that leverage technology and global connectivity, but also the power of group learning and “South->North” capacity building. The course was organized into four themes, with each day beginning with the presentation, discussion and comparison of two representative clinical cases of the same health problem from two very different settings (Table 1). The course was very successful and received strong favorable feedback from students at Hopkins, as well as in the other four partners institutions. The ability to interact with each other through live video conferencing enriched the global health learning experience for all15. However, the use of this high tech distance learning platform also provided many wonderful opportunities to discuss the limitations of technology. The Hopkins students, who were attentively engaged by their open laptops during the class, were challenged by questions about why they needed to use their cell phones and lap tops during the class, from the Ethiopian students, who were focused and engaged in the discussion without the help these devices (Figure 4). The Ugandan medical students asked the Hopkins students whether they were taught to use stethoscopes, during the discussion of the two pediatric pneumococcal pneumonia cases, when the diagnostic work up of the child in Baltimore was described and included CT scan of the chest, as well as multiple sub-specialty consultations and a 14 day hospital course. The child from Uganda, with the same diagnosis, the same antibiotic treatment and the same successful clinical outcome, was diagnosed with an excellent physical exam and CXR. He also was discharged home from the hospital after two inpatient days on oral antibiotics. The use of distance learning technology to facilitate these discussions of global health issues, ironically provided a tremendously valuable opportunity for the Hopkins students to learn from their colleagues in Ethiopia, Uganda, Pakistan and India about the limits of technology, as well as the importance of professionalism and a good physical exam.

Table 1.

Hopkins Medical Student Global Health Course Live Video Conference Case Discussions

| Theme | Clinical Cases | Partner Institutes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | Maternal Health |

High Risk Pregnancy in Baltimore and Addis Ababa |

Addis Ababa University Black Lion Hospital |

| Day 2 | Child Health |

Pediatric Pneumonia in Baltimore and Kampala |

Makerere University Mulago Hospital |

| Day 3 | Emerging Diseases |

MDR-TB in Baltimore and Karachi |

Indus Hospital |

| Day 4 | Chronic Diseases |

Coronary Artery Disease in Baltimore and Pune |

BJ Medical College Sassoon Hospital |

Figure 4.

Hopkins First Year Medical Student Global Health Case Discussion with Addis Ababa University and Black Lion Hospital in Ethiopia

Distance Learning Can and Must be Evaluated

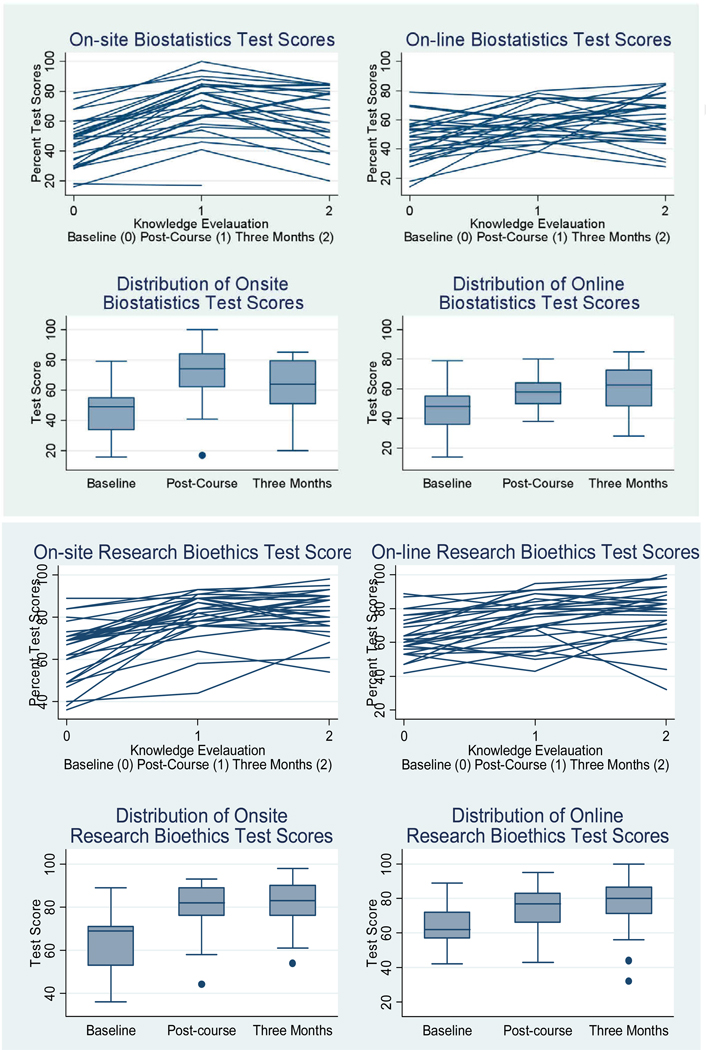

On-line learning has been widely utilized for education in the US and other developed country settings, where its effectiveness has been demonstrated16. As outlined above, while distance education is also increasingly supporting the training of students in resource-limited settings, evaluations of the impact and acceptance of distance learning platforms in such settings are limited. To better understand the potential value of on-distance education to expand health research capacity, the CCGHE undertook a randomized study comparing on-line with on-site (i.e. face-to-face) delivery of courses in two distinct domains relevant for international health research: Biostatistics and Research Ethics 17. Our hypothesis was that both on-site and on-line course formats would lead to similar gains in knowledge for students, for both content domains.

Fifty-eight volunteer Indian scientists were randomly assigned to one of two arms. Students in Arm 1 attended a 3.5-day on-site course in Biostatistics and completed a 3.5-week on-line course in Research Ethics. Students in Arm 2 attended a 3.5-week on-line course in Biostatistics and 3.5-day on-site course in Research Ethics. For the two course formats, learning objectives and knowledge tests were identical, and course contents were comparable. We assessed improvement in knowledge immediately and 3-months after course completion, compared to baseline. Baseline characteristics were similar in both arms. As shown in Figure 5, immediate median gains in knowledge scores were similar between the on-site and on-line platforms for both Biostatistics and Research Ethics. The increase in knowledge gain was sustained 3 months after completion of the courses and remained similar for the on-site and on-line format.

Figure 5.

Comparison of Knowledge Gain between On-line and On-site Courses in Biostatistics and Research Ethics.

In summary, our evaluation of this distance education program in India, demonstrated that on-line and on-site training formats led to marked and similar improvements of knowledge in Biostatistics and Research Ethics. This, combined with logistical and cost advantages of on-line training, may make on-line courses particularly useful for expanding health research capacity in resource-limited settings. Our experience also demonstrates that pre- and post course knowledge assessments, as well as student course evaluations can be easily deployed and monitored, even for learners in remote areas. In addition to interactive learning tools deployed on-line, wireless devices can also be used to both deliver and evaluate training programs. While randomized study designs are not always feasible or necessary for evaluation of distance education programs, rigorous evaluations should be a responsibility and priority for health programs that utilize them.

Distance Learning Limitations and Benefits

Distance learning tools are designed to supplement and support capacity building programs, not to replace other more traditional training platforms. As with any education strategy, distance learning tools have limitations. The optimal use of these tools requires an understanding of the required infrastructure and technological support. Structural barriers such as limited fiber networks, bandwidth and wireless network architecture, as well as lack of access to computers, can be important barriers to the effective use of distance learning technology. In some cases, students lack the experience and training required to use the technologies. While cell phones are ubiquitous and may be optimal tools for many settings, many individuals may be unfamiliar with computers. These challenges require any capacity building program using distance learning platforms to have a clear understanding of which tools will work optimally in their own settings. In many settings, distance learning may provide access to basic information, but higher level training, particularly clinical or laboratory skills, will still require hands-on training, as well as face-to-face mentorship or group interactions. In addition, effective health care delivery requires that providers and patients develop trust and familiarity with each other. It would be a mistake for technology to replace or interfere with the human-to-human interactions that are so important for our students to experience and learn.

Despite these important limitations, when carefully designed and implemented, distance learning tools provide a unique opportunity to expand access to training and clinical care support for resource-limited providers and communities (Box 1). The flexibility of these tools can prioritize important, local competencies and training gaps. Our CCGHE experience suggests that distance learning tools can rapidly deliver new information and adapt to changing local needs. They are feasible to implement, even in very remote communities in Asia, Africa and Latin America. In general, the lower cost of deployment increases the accessibility and scalability of training programs, making distance learning more cost-effective and sustainable for resource-constrained communities. Distance learning is also a “green” technology, which limits the need for travel for both learners and trainers. In contrast to live workshops or face-to-face lectures, distance learning also allows capturing the very best available training, as well as for more consistent delivery of the highest quality training content to many different settings. Interactive distance learning platforms also allow for content delivery to adapt to the understanding and experience of learners, leading to broad utility for students with diverse literacy, experience and prior education. In addition, as opposed to more traditional education strategies that “push” content to learners, distance education is a “pull” platform that requires learners to access and use the content. Therefore, distance learners are active learners. They will only use and demand content that is valuable to them. This provides additional incentive to education programs that use distance learning technology to optimize their content.

Distance learning can therefore be empowering of local providers and, perhaps, limit “brain drain”. The flexibility and convenience of distance learning tools allow providers to access training and clinical care support at their point-of-care, their own homes or their local communities. Typically they can also more easily control the timing of their training. In summary, distance learning programs empower the learner and limit the need for providers to leave their communities to access high quality training.

The future scale and acceptability of distance learning tools to support global health education will ultimately depend on clear demonstration of impact and value. There is a great need for rigorous evaluation and monitoring of distance learning programs. As with any training program, distance education programs must lead to improved clinical practice and improved health for the communities and patients. While technology and innovation is leading to greater opportunities for distance learning, in communities around the world, there is also an opportunity and responsibility to properly evaluate and monitor these programs.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Robert C. Bollinger, Professor of Infectious Diseases and International Health, Director, Center for Clinical Global Health Education, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Phipps 540, 600 N. Wolfe Street, Baltimore, Maryland, 21286, rcb@jhmi.edu, 410-614-0936.

Jane McKenzie-White, Managing Director, Center for Clinical Global Health Education, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Phipps 540, 600 N. Wolfe Street, Baltimore, Maryland, 21286, jmw@jhmi.edu, 410-502-2029.

Amita Gupta, Assistant Professor of Infectious Diseases and International Health, Deputy Director, Center for Clinical Global Health Education, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Phipps 540, 600 N, Wolfe Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21287, USA. agupta25@jhmi.edu, 410-502-7696.

References

- 1.Johns Hopkins Center for Clinical Global Health Education. [online] [Accessed 19 November 2010];2010 Available from World Wide Web: http://www.ccghe.jhmi.edu/ccg/index.asp.

- 2.Moodle Course Management System. [online] [Accessed 19 November 2010];2010 Available from World Wide Web: http://moodle.org/

- 3.Huddart J, Furth R, Lyons J. U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) Contract Number GPH-C-00-02-00004-00. The Zambia HIV/AIDS Workforce Study: Preparing for Scale-up. April 2004 Repor of he Quality Assurance Project (QAP) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johns Hopkins Center for Clinical Global Health Education. Global Vision-Delivering web-based education around the world [online] [Accessed 19 November 2010];2010 Available from World Wide Web: http://www.ccghe.net/video/1GlobalVision.html.

- 5.Johns Hopkins Center for Clinical Global Health Education. HIV Clinical Care Discussions in Ethiopia [online] [Accessed 19 November 2010];2010 Available from World Wide Web: http://www.ccghe.jhmi.edu/CCG/distance/HIV_Courses/Ethiopiaart.asp.

- 6.Johns Hopkins Center for Clinical Global Health Education. HIV Clinical Care Discussions in India [online] [Accessed 19 November 2010];2010 Available from World Wide Web: http://www.ccghe.jhmi.edu/CCG/distance/HIV_Discussions_India/

- 7.Johns Hopkins Center for Clinical Global Health Education. Continuing Medical Education Course for Family Practitioners in Palestine [online] [Accessed 19 November 2010];2010 Available from World Wide Web: http://moodle.ccghe.net/course/view.php?id=48.

- 8.World Health Organization. Global recommendations and guidelines on task shifting. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, Makumbi F, Watya S, Nalugoda F, Kiwanuka N, Moulton LH, Chaudhary MA, Chen MZ, Sewankambo NK, Wabwire-Mangen F, Bacon MC, Williams CF, Opendi P, Reynolds SJ, Laeyendecker O, Quinn TC, Wawer MJ. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in men in Rakai, Uganda: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2007 Feb 27;369(9562):657–666. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60313-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization and Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Operational guidance for scaling up male circumcision services for HIV prevention [online] [Accessed 19 November 2010];2008 Available from World Wide Web: http://www.malecircumcision.org/programs/documents/MC_OpGuideFINAL_web.pdf.

- 11.Kiggundu V, Watya S, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, Nalugoda F, Buwembo D, Settuba A, Anyokorit M, Nkale J, Kighoma N, Sempiija V, Wawer M, Gray RH. The number of procedures required to achieve optimal competency with male circumcision: findings from a randomized trial in Rakai, Uganda. BJU Int. 2009 August;104(4):529–532. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08420.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation Grand Challenges in Global Health Round 5 March 2010. Create Low-cost Cell Phone-based Applications for Priority Global Health Conditions. [online] [Accessed 19 November 2010]; Available from World Wide Web: http://www.grandchallenges.org/MeasureHealthStatus/Topics/CellPhoneApps/Pages/Round5.aspx.

- 13.The Rockefeller Foundation. From Silos to Systems: An Overview of eHealth’s Transformative Power Rockefeller Foundation Report / Bellagio Center Conference Series / January 13, 2010. [online] [Accessed 19 November 2010]; Available from World Wide Web: http://www.rockefellerfoundation.org/news/publications/from-silos-systems-overview-ehealth.

- 14.mHealth Alliance. [online] [Accessed 19 November 2010]; Available from World Wide Web: http://www.mhealthalliance.org/

- 15.Johns Hopkins Center for Clinical Global Health Education. Global Health Course for Medical Students. Emerging Infections Case Discussion: Indus Hospital in Karachi and Johns Hopkins in Baltimore. [online] [Accessed 19 November 2010];2010 March; Available from World Wide Web: http://moodle.ccghe.net/media/IndusHospital.mp4.

- 16.US Department of Education, Office of Planning, Evaluation and Policy Development. Washington DC: 2009. [Accessed 19 November 2010]. Evaluation of evidence-based practices in online learning: a meta-analysis and review of online learning studies. [online] Available from World Wide Web: http://www.ed.gov/about/offices/list/opepd/ppss/reports.html. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aggarwal R, Gupte N, Kass N, Taylor H, Ali J, Bhan A, Aggarwal A, Sisson SD, Kanchanaraksa S, McKenzie-White J, McGready J, Miotti P, Bollinger RC. Distance Learning to Build International Health Research Capacity: A Randomized Study of Online versus On-site Training. (Unpublished Data: Manuscript Under Review) [Google Scholar]