Abstract

Background

Clinical trials are critical for evaluating new cancer therapies, but few adult patients participate in them. Physicians have an important role in facilitating patient participation in clinical trials. We examined the characteristics of specialty physicians who participate in clinical trials by enrolling or referring patients, the types of trials in which they participate, and factors associated with physicians who report greater involvement in clinical trials.

Methods

We analyzed data from the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium. The study included 1533 specialty physicians who cared for colorectal and lung cancer patients (496 medical oncologists, 228 radiation oncologists, and 809 surgeons) and completed a survey conducted during 2005–2006 (response rate = 61.0%). Descriptive statistics were used to characterize physicians’ personal and practice characteristics, and regression models were used to examine associations between these characteristics and physician participation in clinical trials. All statistical tests were two-sided.

Results

A total of 87.8% of medical oncologists, 66.1% of radiation oncologists, and 35.0% of surgeons reported referring or enrolling one or more patients in clinical trials during the previous 12 months. The mean number of patients referred or enrolled by these physicians was 17.2 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 15.5 to 18.9) for medical oncologists, 9.5 (95% CI = 7.7 to 11.3) for radiation oncologists, and 12.2 (95% CI = 9.8 to 14.6) for surgeons (P < .001). Specialty type, involvement in teaching, and affiliation with a Community Clinical Oncology Program (CCOP) and/or a National Cancer Institute–designated cancer center were associated with physician trial participation and enrolling more patients (all Ps < .05). Two-thirds of physicians with a CCOP or National Cancer Institute–designated cancer center affiliation reported participating in trials.

Conclusions

Features of specialty physicians’ practice environments are associated with their trial participation, but many physicians at CCOPs and cancer centers do not participate.

CONTEXT AND CAVEATS

Prior knowledge

Although clinical trials are essential for evaluating new cancer therapies, a small proportion of adult patients participate in them. Physicians have an important role in facilitating patient participation in clinical trials.

Study design

A survey-based study of specialty physicians who cared for colorectal and lung cancer patients was conducted to identify those who participated in clinical trials by enrolling or referring patients, the types of trials in which they participated, and factors associated with greater involvement in clinical trials.

Contribution

Features of specialty physicians’ practice environments were associated with their trial participation in the full study population, and the patterns of associations were similar for physicians who were affiliated with a Community Clinical Oncology Program and/or a National Cancer Institute–designated cancer center (environments specifically designed to support physicians’ clinical trials involvement).

Implications

Closer examination of nonparticipating physicians in these settings might identify incentives that could be used to increase their willingness to participate in clinical trials.

Limitations

Physician participants were not a nationally representative sample, and the clinical trials involvement of respondents may have differed from those who did not respond to the survey. No information was collected about physicians’ beliefs about or attitudes toward clinical research or trials. The number of patients referred vs the number enrolled was not estimated separately, nor did the study control for overall patient volume. Detailed information about the characteristics of the patients was not obtained.

From the Editors

Cancer clinical trials are research studies designed to determine the safety and efficacy of new approaches to preventing, diagnosing, and treating cancer. They are critical to the discovery of new and improved therapies for cancer patients. According to the National Cancer Institute (NCI), more than 8000 clinical trials are accepting participants (1). However, it has been estimated that only 2%–4% of newly diagnosed adult cancer patients participate in clinical trials (2,3). Barriers to patient participation in clinical trials include the additional medical appointments and procedures required by many trial protocols and the concomitant travel time and costs (4). Many patients are also uncertain about or suspicious of medical research (5). Furthermore, the patient’s physicians may pose a barrier to participation: Two studies (2,6) have noted that the majority of eligible cancer patients are not enrolled in clinical trials because their physicians decided to not offer trials to them.

Physicians have an important role in making patients aware of clinical trials, informing them of the benefits and risks of trial participation, and facilitating referral or enrollment for those who are willing to consider participating in a trial (7–9). The literature on physician participation in cancer clinical trials is relatively sparse, and most of the published studies have had small sample sizes of 500 or fewer physicians and were conducted in only a handful of centers or a single geographic area (2,10–17). These studies have typically assessed reasons why physicians do not participate in clinical trials or enroll more patients in them (2,4,10–14,17,18). Few studies have examined the characteristics of physicians who do participate in cancer clinical trials, the settings in which they practice, and the types of trials in which they participate (6,9).

The Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium (CanCORS) initiative (19,20) presents a unique opportunity to study these issues and to address this important gap in the literature. CanCORS is a multisite national effort to examine the care and outcomes experienced by more than 10 000 patients diagnosed with lung or colorectal cancer in the United States. CanCORS comprises population-based and health system–based cohorts of cancer patients; the CanCORS study population has been found to be generally representative of cancer patients in the United States (21). Preliminary analyses by CanCORS investigators suggest that approximately 5% of CanCORS patients were enrolled in a clinical trial following their cancer diagnosis. Understanding factors associated with participation in cancer clinical trials is one of the key questions that CanCORS is designed to address (19). This study of physicians who care for CanCORS patients focuses on the provider context, which is a component of the behavioral model of health care developed by Andersen and Aday (22,23) and an important but relatively unexplored factor influencing health-care utilization in the United States (24). The aims of this study were 1) to describe the personal and practice characteristics of specialty physicians who participate in clinical trials and the types of trials in which they participate, 2) to compare clinical trials participation between medical and radiation oncologists and surgeons, and 3) to examine factors associated with specialty physicians who report greater clinical trials involvement.

Participants and Methods

Study Design

The physicians who were included in this study cared for CanCORS patients who were diagnosed with lung or colorectal cancer from September 2003 to December 2005 while residing in one of five geographic regions (Northern California, Los Angeles County, North Carolina, Iowa, Alabama) or while receiving care in one of five large health maintenance organizations (Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound, Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, Henry Ford Health System, Kaiser Permanente Northwest, and Kaiser Permanente Hawaii) or at one of 15 Veteran’s Health Administration hospitals in the United States. CanCORS data were obtained from patients, physicians, caregivers, and medical records; data collection procedures were approved by the human subjects committees at participating institutions, which also approved the survey protocol. Further details on study design and procedures have been described (19,25). This study uses data from the survey of patients’ physicians.

A total of 6871 physicians who were named by CanCORS patients as filling one or more key roles in their care were surveyed by mail from July 2004 through March 2007; 97% of the surveys were mailed during January 2005 through May 2006. A total of 4188 physicians responded, for a survey participation rate of 61.0%. For this study, we included physicians who identified themselves as medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, or surgeons, and who had completed a questionnaire for one of these provider types (n = 1860). We did not include physicians who self-identified as other specialty types because the survey questions on clinical trials participation were asked only of these providers. We excluded physicians who were very recent medical school graduates (ie, within 6 years of medical school graduation for surgeons, within 5 years for medical oncologists, and within 4 years for radiation oncologists) and thus likely to still be in training (n = 137), and those with missing or incomplete data for key variables in the analysis (n = 190), such as year of medical school graduation and clinical trials participation. The final study population included 1533 physicians.

Survey Data

The CanCORS survey asked physicians to estimate the number of patients they had enrolled or referred for enrollment in any clinical trials during the previous 12 months. Those who reported referring or enrolling one or more patients were asked to specify (yes or no) whether they had participated in the following types of trials: 1) those run by NCI-sponsored clinical trials groups (ie, Cancer and Leukemia Group B, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project, Southwest Oncology Group); 2) those run by non–NCI-sponsored clinical trials groups (ie, US Oncology Group); or 3) pharmaceutical industry–sponsored trials.

The physicians were asked whether the hospital they were affiliated with or their practice was part of a Community Clinical Oncology Program (CCOP) or whether they practiced at an NCI-designated cancer center. They were also asked how their income might change as a result of enrolling more patients in clinical trials (likely to increase, likely to decrease, not likely to change, or don’t know). Other survey items asked physicians to estimate how many patients they see each month, on average, for treatment or evaluation of colorectal and/or lung cancer, the number of minutes they typically allocate to meeting with a newly diagnosed cancer patient who is considering treatment options, and the frequency with which they attend multidisciplinary meetings of physicians to discuss cancer patient care, sometimes referred to as tumor board meetings (weekly, monthly, quarterly, less than quarterly, or never).

The survey collected additional information on physicians’ demographic, practice, and patient characteristics. Instruments are available, by request, at: http://www.cancors.org/public. Most of the items on the survey were closed ended, and physicians were asked to choose from among discrete response categories.

Statistical Analysis

Item nonresponse for the survey was less than 3% for most variables; multiple imputation was used to impute missing data for most survey items (26,27). We examined frequency distributions to develop groupings for responses to three open-ended survey items because of the categorical nature of most of the data in this study and to facilitate their comparison across provider types and interpretation in models with limited dependent variables. Practice size was categorized as 1–5, 6–10, 11–20, or 20 or more physicians; number of colorectal and lung cancer patients seen per month was categorized as less than 5, 5–9, 10–19, or 20 or more; and time spent with a newly diagnosed cancer patient was categorized as less than 60 minutes or 60 or more minutes. Although the cut point for time spent was roughly based on the overall median for the three provider types combined, we chose this cut point primarily based on clinical input that 60 minutes is an appropriate and optimal visit time allocation for a newly diagnosed cancer patient.

We used descriptive statistics to summarize physicians’ demographic, practice, patient, and practice style characteristics, and clinical trial participation by provider type. We used regression modeling to examine factors associated with physician involvement in clinical trials. We estimated separate models for medical and radiation oncologists combined and for surgeons because of the relatively small number of radiation oncologists and because many trials of adjuvant therapy and metastatic lung and colorectal cancers use interventions that combine radiation and chemotherapy. For both models, logistic regression was used to assess the association of physicians’ personal and practice characteristics with their clinical trials involvement. The dependent variable was a dichotomous measure of whether the physician had referred or enrolled one or more patients in clinical trials during the previous 12 months. The odds ratios produced by the models compared the odds of participating in clinical trials with the odds of not participating. We also estimated adjusted percentages of physicians who referred or enrolled patients in clinical trials (ie, predictive margins) from the models by controlling for all covariates listed in Table 1 (28,29). The predictive margin for a specific group represents the average predicted response if everyone in the study population had been in that group. To further examine whether characteristics of physicians who participated in clinical trials and whose practice was affiliated with a CCOP or an NCI-designated cancer center differed from the full study population, we repeated the modeling and restricted the analysis to the 760 physicians (49.6%) who reported a CCOP or NCI-designated cancer center affiliation. Because of the smaller sample size, we did not estimate separate models by specialty type in this secondary analysis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium physicians and their practice settings (N = 1533)*

| Characteristic | Medical oncologists | Radiation oncologists | Surgeons |

| No. (% of total) | 496 (32.4) | 228 (14.9) | 809 (52.7) |

| Physicians, No. (%) | |||

| Age, y | |||

| <50 | 245 (49.5) | 112 (49.2) | 379 (46.9) |

| 50–59 | 183 (37.0) | 62 (27.3) | 267 (33.0) |

| ≥60 | 67 (13.5) | 54 (23.5) | 163 (20.1) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 376 (75.8) | 181 (79.4) | 727 (89.8) |

| Female | 120 (24.2) | 47 (20.6) | 82 (10.2) |

| US or Canadian medical school graduate | |||

| Yes | 380 (76.6) | 197 (86.4) | 720 (89.0) |

| No | 116 (23.4) | 31 (13.6) | 89 (11.0) |

| Practice setting, No. (%) | |||

| Income increases as a result of enrolling patients on clinical trials | |||

| Yes | 62 (12.5) | 13 (5.7) | 16 (2.0) |

| No | 434 (87.5) | 215 (94.3) | 793 (98.0) |

| Practice type | |||

| Office based, solo | 52 (10.5) | 4 (1.8) | 129 (16.2) |

| Office based, group† | 275 (55.8) | 57 (25.1) | 244 (30.8) |

| Hospital based | 167 (33.7) | 156 (73.1) | 421(53.0) |

| Practice size, No. of physicians | |||

| 1–5 | 241 (48.6) | 140 (61.5) | 439 (54.2) |

| 6–10 | 87 (17.6) | 47 (20.5) | 144 (17.9) |

| 11–20 | 84 (16.9) | 21 (9.3) | 71 (8.8) |

| >20 | 84 (16.9) | 20 (8.7) | 154 (19.1) |

| Study site | |||

| Five large HMOs‡ | 39 (7.9) | 22 (9.7) | 63 (7.8) |

| Northern California counties | 124 (25.0) | 48 (21.0) | 207 (25.6) |

| Los Angeles County | 115 (23.2) | 51 (22.4) | 187 (23.1) |

| State of Alabama | 51 (10.3) | 31 (13.6) | 142 (17.6) |

| State of Iowa | 52 (10.5) | 28 (12.3) | 40 (4.9) |

| State of North Carolina | 51 (10.2) | 23 (10.0) | 114 (14.1) |

| Veteran’s Administration | 64 (12.9) | 25 (11.0) | 56 (6.9) |

| Practice affiliated with a CCOP | |||

| Yes | 165 (33.2) | 93 (41.0) | 267 (33.0) |

| No | 331 (66.8) | 135 (59.0) | 542 (67.0) |

| Practice affiliated with an NCI-designated cancer center | |||

| Yes | 110 (22.1) | 49 (21.4) | 236 (29.2) |

| No | 386 (77.9) | 179 (78.6) | 573 (70.8) |

| Physician practice style, No. (%) | |||

| Percentage of patients in managed care, quartiles | |||

| 0–20 | 143 (28.7) | 61 (26.7) | 166 (20.5) |

| 21–49 | 113 (22.8) | 61 (26.8) | 152 (18.8) |

| 50–78 | 101 (20.4) | 66 (29.0) | 230 (28.4) |

| 79–100 | 139 (28.1) | 40 (17.5) | 262 (32.3) |

| Teaches medical students and/or residents | |||

| Yes | 259 (52.3) | 94 (41.2) | 420 (51.9) |

| No | 237 (47.7) | 134 (58.8) | 389 (48.1) |

| Attends tumor board meetings | |||

| Weekly | 334 (67.4) | 187 (81.9) | 279 (34.5) |

| Monthly | 109 (22.0) | 32 (14.1) | 262 (32.3) |

| Quarterly or less frequently | 53 (10.6) | 9 (4.0) | 269 (33.2) |

| No. of colorectal or lung cancer patients seen per month | |||

| <5 | 40 (8.0) | 42 (18.6) | 525 (65.0) |

| 5–9 | 65 (13.0) | 69 (30.4) | 136 (16.8) |

| 10–19 | 97 (19.6) | 69 (30.1) | 97 (12.0) |

| ≥20 | 294 (59.4) | 48 (20.9) | 50 (6.2) |

| Time spent with a newly diagnosed cancer patient, min | |||

| <60 | 181 (36.5) | 36 (16.0) | 658 (81.4) |

| ≥60 | 315 (63.5) | 192 (84.0) | 151 (18.6) |

CCOP = Community Clinical Oncology Program; HMO = health maintenance organization; NCI = National Cancer Institute.

Includes office-based HMOs, community health centers, and other (a questionnaire item).

Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound, Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, Henry Ford Health System, Kaiser Permanente Northwest, and Kaiser Permanente Hawaii.

To examine factors associated with physicians who enrolled a higher volume of patients in clinical trials, we estimated two additional models using Poisson regression. These models were restricted to physicians who had referred or enrolled at least one patient in a clinical trial. The first model included medical and radiation oncologists, and the second model included surgeons. The dependent variable was the number of patients referred or enrolled in the previous 12 months. The associations between the dependent variable and explanatory variables in these models are characterized using expected count ratios (CRs). The numerator of the count ratio is the expected number of patients referred or enrolled for the group of interest, and the denominator is the expected number for the reference group. For example, a count ratio of 1.27 for medical oncologists relative to radiation oncologists indicates that medical oncologists referred or enrolled 27% more patients compared with radiation oncologists, all other model covariates held constant. Because several large outlier values of the dependent variable caused pronounced right skewness of the data and contributed to overdispersion of the Poisson models, we assigned a maximum value of 30 patients per year to the 78 oncologists and 29 surgeons who indicated that they had referred or enrolled more than 30 patients per year. Thus, the range of the dependent variable was 1–30. To assess the robustness of our results, we also estimated zero-inflated Poisson regression models (30) and obtained results that were qualitatively similar to those of our separate logistic and Poisson regression modeling approaches (data not shown).

All analyses were conducted using SUDAAN release 10.0.1 software (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC) and CanCORS survey dataset version 1.6.1, which was finalized in March 2007. All statistical tests were two-sided, and a P value of .05 was considered statistically significant. The P values in Tables 2–4 are based on an overall Wald χ2 test for association from the multivariate regression models.

Table 2.

Multiple logistic regression models assessing characteristics associated with specialty physicians who refer or enroll patients in clinical trials (N = 1533)*

| Characteristic | Medical and radiation oncologists (n = 721) |

Surgeons (n = 794) |

||||

| Adjusted OR† (95% CI) | Adjusted percentage‡ (95% CI) | P§ | Adjusted OR† (95% CI) | Adjusted percentage‡ (95% CI) | P§ | |

| Physicians | ||||||

| Specialty | ||||||

| Medical oncology | 5.2 (2.8 to 9.4) | 87.9 (84.9 to 91.0) | <.001 | — | — | .010 |

| Radiation oncology | 1.00 (referent) | 66.2 (59.1 to 73.3) | — | — | ||

| General surgery | — | — | 1.00 (referent) | 31.9 (27.8 to 36.0) | ||

| Colorectal surgery | — | — | 1.0 (0.5 to 2.0) | 31.3 (19.6 to 43.1) | ||

| Thoracic surgery | — | — | 1.3 (0.7 to 2.2) | 35.9 (27.2 to 44.6) | ||

| Surgical oncology | — | — | 3.9 (1.8 to 8.6) | 58.3 (43.2 to 73.3) | ||

| Other surgical subspecialty | — | — | 2.1 (0.8 to 5.5) | 46.0 (27.8 to 64.2) | ||

| Age, y | ||||||

| <50 | 1.7 (1.0 to 3.1) | 82.7 (78.7 to 86.7) | .203 | 1.2 (0.7 to 1.9) | 36.6 (31.8 to 41.4) | .413 |

| 50–59 | 1.5 (0.8 to 2.8) | 81.4 (76.8 to 86.1) | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.5) | 31.9 (26.7 to 37.2) | ||

| ≥60 | 1.00 (referent) | 76.0 (69.4 to 82.6) | 1.00 (referent) | 33.9 (27.0 to 40.7) | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1.00 (referent) | 79.6 (76.2 to 82.9) | .068 | 1.00 (referent) | 34.3 (30.8 to 37.8) | .726 |

| Female | 1.8 (1.0 to 3.3) | 86.0 (80.6 to 91.3) | 1.1 (0.6 to 2.1) | 36.2 (26.0 to 46.4) | ||

| US or Canadian medical school graduate | ||||||

| Yes | 1.00 (referent) | 79.9 (76.7 to 83.2) | .136 | 1.00 (referent) | 34.0 (30.5 to 37.5) | .355 |

| No | 1.6 (0.9 to 3.0) | 85.1 (79.6 to 90.7) | 1.3 (0.7 to 2.4) | 38.9 (28.7 to 49.1) | ||

| Practice setting | ||||||

| Income increases as a result of enrolling patients on clinical trials | ||||||

| Yes | 1.9 (0.7 to 5.1) | 87.0 (78.3 to 95.6) | .214 | 0.9 (0.3 to 2.9) | 33.5 (14.6 to 52.5) | .919 |

| No | 1.00 (referent) | 80.3 (77.3 to 83.4) | 1.00 (referent) | 34.5 (31.2 to 37.9) | ||

| Practice type | ||||||

| Office based, solo | 0.3 (0.1 to 0.6) | 65.5 (53.8 to 77.2) | .018 | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.6) | 32.5 (23.2 to 41.8) | .673 |

| Office based, group‖ | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.4) | 81.0 (76.4 to 85.6) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.3) | 32.9 (27.0 to 38.7) | ||

| Hospital based | 1.00 (referent) | 83.8 (79.6 to 88.0) | 1.00 (referent) | 36.0 (31.2 to 40.8) | ||

| Practice size, No. of physicians | ||||||

| 1–5 | 1.00 (referent) | 78.4 (74.3 to 82.5) | .290 | 1.00 (referent) | 32.2 (27.6 to 36.9) | .251 |

| 6–10 | 1.6 (0.8 to 3.1) | 84.0 (77.7 to 90.4) | 1.1 (0.6 to 1.8) | 33.0 (25.7 to 40.4) | ||

| 11–20 | 1.7 (0.6 to 4.4) | 84.5 (75.3 to 93.6) | 1.8 (0.9 to 3.5) | 42.6 (31.4 to 53.8) | ||

| >20 | 2.4 (0.8 to 7.3) | 88.0 (79.3 to 96.7) | 1.5 (0.9 to 2.4) | 38.8 (31.1 to 46.4) | ||

| Study site | ||||||

| Five large HMOs¶ | 1.00 (referent) | 83.0 (73.9 to 92.0) | .129 | 1.00 (referent) | 46.9 (34.4 to 59.3) | .004 |

| Northern California counties | 1.0 (0.4 to 2.6) | 82.6 (76.9 to 88.4) | 0.5 (0.3 to 1.0) | 34.3 (28.1 to 40.5) | ||

| Los Angeles County | 0.8 (0.3 to 2.1) | 80.2 (74.4 to 85.9) | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.9) | 30.9 (24.4 to 37.3) | ||

| State of Alabama | 1.1 (0.4 to 3.4) | 84.2 (77.4 to 91.1) | 0.3 (0.1 to 0.7) | 25.0 (17.7 to 32.2) | ||

| State of Iowa | 1.0 (0.3 to 3.1) | 83.0 (74.8 to 91.1) | 1.0 (0.4 to 2.6) | 46.6 (32.2 to 61.1) | ||

| State of North Carolina | 1.0 (0.3 to 3.2) | 83.2 (74.5 to 91.8) | 0.9 (0.4 to 2.1) | 45.6 (36.4 to 54.9) | ||

| Veteran’s Administration | 0.3 (0.1 to 0.8) | 65.9 (55.0 to 76.9) | 0.4 (0.1 to 1.0) | 29.0 (18.2 to 39.9) | ||

| Practice affiliated with a CCOP | ||||||

| Yes | 2.1 (1.2 to 3.7) | 86.1 (81.7 to 90.5) | .016 | 1.4 (1.0 to 2.0) | 38.3 (32.6 to 44.0) | .094 |

| No | 1.00 (referent) | 77.8 (73.9 to 81.7) | 1.00 (referent) | 32.6 (28.6 to 36.6) | ||

| Practice affiliated with an NCI-designated cancer center | ||||||

| Yes | 2.8 (1.2 to 6.4) | 89.7 (83.5 to 95.8) | .023 | 1.7 (1.1 to 2.6) | 41.4 (34.9 to 47.9) | .010 |

| No | 1.00 (referent) | 79.2 (75.9 to 82.5) | 1.00 (referent) | 31.6 (27.7 to 35.5) | ||

| Physician practice style | ||||||

| Percentage of patients in managed care, quartiles | ||||||

| 0–20 | 0.9 (0.4 to 1.9) | 79.6 (73.8 to 85.4) | .759 | 1.7 (0.9 to 2.9) | 37.5 (30.1 to 44.8) | .190 |

| 21–49 | 1.3 (0.5 to 3.3) | 83.8 (77.6 to 90.0) | 1.8 (1.0 to 3.4) | 39.4 (31.6 to 47.1) | ||

| 50–78 | 0.9 (0.4 to 2.0) | 79.9 (73.8 to 86.1) | 1.5 (0.9 to 2.5) | 36.1 (30.0 to 42.3) | ||

| 79–100 | 1.00 (referent) | 80.8 (74.0 to 87.7) | 1.00 (referent) | 29.1 (23.4 to 34.8) | ||

| Teaches medical students and/or residents | ||||||

| Yes | 2.7 (1.5 to 5.0) | 87.4 (83.2 to 91.7) | .003 | 1.6 (1.1 to 2.4) | 38.4 (33.7 to 43.1) | .019 |

| No | 1.00 (referent) | 75.8 (71.2 to 80.4) | 1.00 (referent) | 30.1 (25.2 to 35.0) | ||

| Attends tumor board meetings | ||||||

| Weekly | 1.1 (0.5 to 2.5) | 82.7 (79.3 to 86.2) | .076 | 2.9 (1.8 to 4.6) | 42.3 (36.3 to 48.3) | <.001 |

| Monthly | 0.6 (0.2 to 1.3) | 74.3 (67.6 to 81.1) | 2.1 (1.3 to 3.5) | 36.6 (30.8 to 42.3) | ||

| Quarterly or less frequently | 1.00 (referent) | 81.7 (72.9 to 90.5) | 1.00 (referent) | 23.9 (18.3 to 29.5) | ||

| No. of colorectal or lung cancer patients seen per month | ||||||

| <5 | 1.00 (referent) | 75.2 (66.5 to 83.9) | .400 | 1.00 (referent) | 28.7 (24.7 to 32.8) | <.001 |

| 5–9 | 1.8 (0.9 to 3.8) | 82.6 (76.8 to 88.3) | 2.0 (1.3 to 3.3) | 41.8 (33.5 to 50.1) | ||

| 10–19 | 1.9 (0.8 to 4.3) | 82.9 (77.3 to 88.5) | 2.1 (1.2 to 3.7) | 42.6 (32.7 to 52.5) | ||

| ≥20 | 1.5 (0.7 to 3.2) | 80.4 (75.9 to 84.9) | 5.1 (2.3 to 11.3) | 60.1 (45.2 to 75.1) | ||

| Time spent with a newly diagnosed cancer patient, min | ||||||

| <60 | 1.00 (referent) | 81.5 (76.2 to 86.8) | .792 | 1.00 (referent) | 34.9 (31.2 to 38.7) | .584 |

| ≥60 | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.6) | 80.6 (77.1 to 84.1) | 0.87 (0.5 to 1.4) | 32.7 (25.5 to 39.8) | ||

— = not applicable; CCOP = Community Clinical Oncology Program; CI = confidence interval; HMO = health maintenance organization; NCI = National Cancer Institute; OR = odds ratio.

Adjusted using multiple logistic regression for all other characteristics in table.

Adjusted using predictive margins for all other characteristics in table.

Based on an overall Wald χ2 test for association obtained from the logistic regression models (two-sided).

Includes office-based HMOs, community health centers, and other (a questionnaire item)

Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound, Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, Henry Ford Health System, Kaiser Permanente Northwest, and Kaiser Permanente Hawaii.

Table 3.

Multiple logistic regression model assessing characteristics associated with specialty physicians who have a CCOP or NCI cancer center affiliation and refer or enroll patients in clinical trials (N = 760)*

| Characteristic | Adjusted OR† (95% CI) | Adjusted percentage‡ (95% CI) | P§ |

| Physicians | |||

| Specialty | |||

| Surgery | 1.00 (referent) | 55.2 (49.2 to 61.2) | <.001 |

| Medical or radiation oncology | 5.1 (2.9 to 9.0) | 80.8 (75.3 to 86.2) | |

| Age, y | |||

| <50 | 1.2 (0.7 to 2.2) | 66.8 (62.0 to 71.5) | .784 |

| 50–59 | 1.2 (0.7 to 2.2) | 66.5 (61.5 to 71.5) | |

| ≥60 | 1.00 (referent) | 63.9 (56.7 to 71.3) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1.00 (referent) | 65.0 (61.3 to 68.7) | .093 |

| Female | 1.7 (0.9 to 3.1) | 72.1 (64.5 to 79.6) | |

| US or Canadian medical school graduate | |||

| Yes | 1.00 (referent) | 65.3 (61.7 to 69.0) | .157 |

| No | 1.6 (0.8 to 2.9) | 71.3 (63.6 to 79.1) | |

| Practice setting | |||

| Income increases as a result of enrolling patients on clinical trials | |||

| Yes | 1.0 (0.4 to 2.7) | 66.5 (53.7 to 79.3) | .953 |

| No | 1.00 (referent) | 66.1 (62.6 to 69.6) | |

| Practice type | |||

| Office based, solo | 0.9 (0.4 to 2.0) | 65.5 (56.1 to 74.9) | .909 |

| Office based, group‖ | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.5) | 65.3 (60.1 to 70.6) | |

| Hospital based | 1.00 (referent) | 66.8 (62.1 to 71.4) | |

| Practice size, No. of physicians | |||

| 1–5 | 1.00 (referent) | 61.4 (56.6 to 66.2) | .019 |

| 6–10 | 2.0 (1.1 to 3.6) | 71.2 (64.3 to 78.2) | |

| 11–20 | 2.4 (1.0 to 5.6) | 73.5 (63.6 to 83.4) | |

| >20 | 2.0 (1.1 to 3.5) | 70.8 (63.9 to 77.7) | |

| Study site | |||

| Five large HMOs¶ | 1.00 (referent) | 74.6 (63.5 to 85.7) | .001 |

| Northern California counties | 0.4 (0.2 to 1.1) | 61.8 (54.9 to 68.7) | |

| Los Angeles County | 0.3 (0.1 to 0.9) | 58.9 (51.7 to 66.0) | |

| State of Alabama | 0.4 (0.1 to 1.0) | 60.0 (52.2 to 67.9) | |

| State of Iowa | 1.5 (0.5 to 4.8) | 79.7 (70.6 to 88.7) | |

| State of North Carolina | 1.1 (0.4 to 3.1) | 75.9 (68.8 to 83.1) | |

| Veteran’s Administration | 0.6 (0.2 to 1.7) | 66.6 (55.5 to 77.7) | |

| Physician practice style | |||

| Percentage of patients in managed care, quartiles | |||

| 0–20 | 1.6 (0.8 to 3.0) | 66.8 (60.0 to 73.5) | .104 |

| 21–49 | 2.2 (1.2 to 4.2) | 71.5 (65.6 to 77.4) | |

| 50–78 | 1.5 (0.9 to 2.6) | 66.1 (60.3 to 71.9) | |

| 79–100 | 1.00 (referent) | 60.5 (54.2 to 66.9) | |

| Teaches medical students and/or residents | |||

| Yes | 3.0 (1. 9 to 4.7) | 73.3 (69.1 to 77.6) | <.001 |

| No | 1.00 (referent) | 57.7 (52.5 to 63.0) | |

| Attends tumor board meetings | |||

| Weekly | 2.8 (1.6 to 5.0) | 71.0 (66.5 to 75.5) | .001 |

| Monthly | 1.7 (1.0 to 3.1) | 63.8 (57.7 to 69.9) | |

| Quarterly or less frequently | 1.00 (referent) | 55.1 (47.1 to 63.1) | |

| No. of colorectal or lung cancer patients seen per month | |||

| <5 | 1.00 (referent) | 60.0 (54.5 to 65.5) | .002 |

| 5–9 | 1.3 (0.7 to 2.4) | 63.8 (55.6 to 72.0) | |

| 10–19 | 1.9 (1.0 to 3.4) | 69.5 (62.3 to 76.7) | |

| ≥20 | 3.4 (1.7 to 6.4) | 77.4 (70.3 to 84.6) | |

| Time spent with a newly diagnosed cancer patient, min | |||

| <60 | 1.00 (referent) | 66.4 (62.0 to 70.8) | .846 |

| ≥60 | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.6) | 65.7 (60.2 to 71.1) | |

CCOP = Community Clinical Oncology Program; CI = confidence interval; HMO = health maintenance organization; NCI = National Cancer Institute; OR = odds ratio.

Adjusted using multiple logistic regression for all other characteristics in table.

Adjusted using predictive margins for all other characteristics in table.

Based on an overall Wald χ2 test for association obtained from the logistic regression model (two-sided).

Includes office-based HMO, community health center, and other (a questionnaire item).

Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound, Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, Henry Ford Health System, Kaiser Permanente Northwest, and Kaiser Permanente Hawaii.

Table 4.

Poisson regression models assessing characteristics associated with specialty physicians who refer or enroll a higher volume of patients in clinical trials (N = 857)*

| Characteristic | Medical and radiation oncologists (n = 582) |

Surgeons (n = 275) |

||

| Adjusted CR (95% CI) | P† | Adjusted CR (95% CI) | P† | |

| Physicians | ||||

| Specialty | ||||

| Medical oncology | 1.27 (1.16 to 1.38) | <.001 | — | .007 |

| Radiation oncology | 1.00 (referent) | — | ||

| General surgery | — | 1.00 (referent) | ||

| Colorectal surgery | — | 1.01 (0.83 to 1.24) | ||

| Thoracic surgery | — | 1.48 (1.25 to 1.76) | ||

| Surgical oncology | — | 1.74 (1.48 to 2.06) | ||

| Other surgical subspecialty | — | 1.60 (1.22 to 2.09) | ||

| Age, y | ||||

| <50 | 1.14 (1.04 to 1.26) | .066 | 0.82 (0.70 to 0.95) | .040 |

| 50–59 | 1.12 (1.01 to 1.23) | 0.75 (0.64 to 0.88) | ||

| ≥60 | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1.00 (referent) | .749 | 1.00 (referent) | .029 |

| Female | 0.99 (0.94 to 1.05) | 1.33 (1.10 to 1.61) | ||

| US or Canadian medical school graduate | ||||

| Yes | 1.00 (referent) | .019 | 1.00 (referent) | .502 |

| No | 0.91 (0.86 to 0.97) | 0.93 (0.74 to 1.16) | ||

| Practice setting | ||||

| Income increases as a result of enrolling patients on clinical trials | ||||

| Yes | 1.20 (1.12 to 1.30) | .001 | 1.38 (1.08 to 1.75) | .050 |

| No | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | ||

| Practice type | ||||

| Office based, solo | 0.91 (0.79 to 1.06) | .038 | 0.82 (0.63 to 1.08) | .162 |

| Office based, group‡ | 1.08 (1.01 to 1.16) | 1.12 (0.98 to 1.29) | ||

| Hospital based | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | ||

| Practice size, No. of physicians | ||||

| 1–5 | 1.00 (referent) | .035 | 1.00 (referent) | .112 |

| 6–10 | 0.98 (0.91 to 1.06) | 0.79 (0.67 to 0.92) | ||

| 11–20 | 1.13 (1.05 to 1.22) | 0.92 (0.78 to 1.07) | ||

| >20 | 1.03 (0.94 to 1.13) | 0.93 (0.81 to 1.07) | ||

| Study site | ||||

| Five large HMOs§ | 1.00 (referent) | .020 | 1.00 (referent) | .065 |

| Northern California Counties | 0.90 (0.82 to 0.99) | 1.14 (0.93 to 1.38) | ||

| Los Angeles County | 0.96 (0.86 to 1.08) | 1.00 (0.78 to 1.27) | ||

| State of Alabama | 1.15 (1.02 to 1.29) | 0.98 (0.80 to 1.19) | ||

| State of Iowa | 1.05 (0.94 to 1.18) | 1.64 (1.31 to 2.06) | ||

| State of North Carolina | 0.98 (0.87 to 1.09) | 1.26 (1.01 to 1.56) | ||

| Veteran’s Administration | 0.99 (0.88 to 1.11) | 1.02 (0.85 to 1.23) | ||

| Practice affiliated with a CCOP | ||||

| Yes | 0.96 (0.91 to 1.02) | .225 | 1.02 (0.92 to 1.13) | .732 |

| No | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | ||

| Practice affiliated with an NCI-designated cancer center | ||||

| Yes | 1.30 (1.21 to 1.39) | <.001 | 1.26 (1.11 to 1.42) | .013 |

| No | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | ||

| Physician practice style | ||||

| Percentage of patients in managed care, quartiles | ||||

| 0–20 | 1.04 (0.95 to 1.14) | .047 | 0.94 (0.74 to 1.19) | .140 |

| 21–49 | 1.13 (1.03 to 1.25) | 0.93 (0.74 to 1.16) | ||

| 50–78 | 1.03 (0.88 to 1.20) | 1.12 (0.94 to 1.34) | ||

| 79–100 | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | ||

| Teaches medical students and/or residents | ||||

| Yes | 1.12 (1.06 to 1.19) | .004 | 1.20 (1.05 to 1.36) | .040 |

| No | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | ||

| Attends tumor board meetings | ||||

| Weekly | 1.15 (1.01 to 1.31) | <.001 | 1.42 (0.82 to 2.44) | .012 |

| Monthly | 0.91 (0.79 to 1.06) | 1.07 (0.55 to 2.07) | ||

| Quarterly or less frequently | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | ||

| No. of colorectal or lung cancer patients seen per month | ||||

| <5 | 1.00 (referent) | <.001 | 1.00 (referent) | .035 |

| 5–9 | 0.93 (0.82 to 1.06) | 1.00 (0.84 to 1.19) | ||

| 10–19 | 0.91 (0.80 to 1.02) | 0.94 (0.83 to 1.07) | ||

| ≥20 | 1.22 (1.12 to 1.34) | 1.29 (1.12 to 1.49) | ||

| Time spent with a newly diagnosed cancer patient, min | ||||

| <60 | 1.00 (referent) | .031 | 1.00 | .099 |

| ≥60 | 1.08 (1.02 to 1.15) | .031 | 0.88 (0.78 to 1.00) | |

| Type of trial participation | ||||

| Pharmaceutical and cooperative groups | 1.00 (referent) | <.001 | 1.00 (referent) | <.001 |

| Pharmaceutical only or cooperative groups only | 0.57 (0.52 to 0.63) | 0.61 (0.55 to 0.67) | ||

| Unknown | 0.63 (0.50 to 0.78) | 0.67 (0.54 to 0.83) | ||

— = not applicable; CCOP = Community Clinical Oncology Program; CI = confidence interval; CR = count ratio (the expected number of patients referred or enrolled for the group of interest divided by the expected number for the reference group); HMO = health maintenance organization; NCI = National Cancer Institute.

Based on an overall Wald χ2 test for association obtained from the Poisson regression models.

Includes office-based HMO, community health center, and other (a questionnaire item).

Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound, Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, Henry Ford Health System, Kaiser Permanente Northwest, and Kaiser Permanente Hawaii.

Results

Characteristics of Specialty Physicians and Their Practice Environments

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the physicians in our study. More than half (52.7%) were surgeons (67.1% were general surgeons, 16.3% were thoracic surgeons, 7.2% were colorectal surgeons, 6.4% were surgical oncologists, and 2.9% were other surgical subspecialists), 32.4% were medical oncologists, and 14.9% were radiation oncologists. Approximately one-half of the physicians were aged 50 years or older, most were male, and they tended to work in small practices comprising one to five physicians.

Most of the surgeons and radiation oncologists were in hospital-based practices, and most of the medical oncologists were in office-based practices. Compared with medical oncologists and surgeons, fewer radiation oncologists were engaged in teaching medical students or residents. Most medical (67.4%) and radiation (81.9%) oncologists attended weekly tumor board meetings, whereas only 34.5% of surgeons did so.

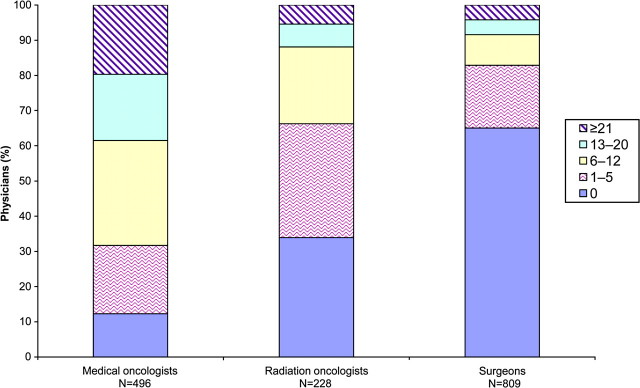

Clinical Trials Participation of Specialty Physicians

A total of 869 physicians (56.7%) reported referring or enrolling at least one patient in cancer clinical trials in the previous 12 months, including 87.8% of medical oncologists, 66.1% of radiation oncologists, and 35.0% of surgeons (Figure 1). Among the physicians who had referred or enrolled at least one patient in cancer clinical trials in the previous 12 months, the mean number of patients referred or enrolled was 17.2 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 15.5 to 18.9) for medical oncologists, 9.5 (95% CI = 7.7 to 11.3) for radiation oncologists, and 12.2 (95% CI = 9.8 to 14.6) for surgeons (P < .001). Among surgeons who had referred or enrolled at least one patient in cancer clinical trials in the previous 12 months, the mean number of patients referred or enrolled varied by surgical specialty: 6.7 (95% CI = 5.3 to 8.1) for general surgeons, 17.8 (95% CI = 11.0 to 24.5) for thoracic surgeons, 9.4 (95% CI = 4.8 to 14.1) for colorectal surgeons, 26.1 (95% CI = 15.3 to 36.9) for surgical oncologists, and 11.8 (95% CI = 4.4 to 19.1) for other surgical subspecialists (P < .001).

Figure 1.

Number of patients referred to or enrolled in cancer clinical trials during the previous year by specialty physicians (N = 1533).

Characteristics associated with physicians who referred or enrolled patients in clinical trials in multivariate analyses are shown in Table 2. Among the nonsurgical specialists in the study population, medical oncologists were more likely to participate in clinical trials than were radiation oncologists (87.9% vs 66.2%; P < .001). Also more likely to participate in clinical trials were physicians affiliated with a CCOP (86.1% vs 77.8%; P = .016) or with an NCI-designated cancer center (89.7% vs 79.2%; P = .023) vs those with no such affiliations, those who taught medical students or residents vs those who did not (87.4% vs 75.8%; P = .003), and those in a hospital-based practice vs those in an office-based solo practice (83.8% vs 65.5%; P = .018).

Among the surgeons in the study population, surgical oncologists were more likely than general surgeons to participate in clinical trials (58.3% vs 31.9%; P = .01). Also more likely to participate in clinical trials were surgeons affiliated with an NCI-designated cancer center compared with those with no such affiliation (41.4% vs 31.6%; P = .01), those who taught medical students or residents compared with those who did not (38.4% vs 30.1%; P = .019), those who saw five or more lung or colorectal cancer patients per month compared with those who saw fewer than five (5–9 vs < 5 patients: 41.8% vs 28.7%; P < .001), and those who attended tumor board meetings on a monthly or weekly basis compared with those who attended meetings quarterly or less frequently (36.6% or 42.3% vs 23.9%; P < .001).

Our secondary analysis of the 760 physicians who reported an affiliation with a CCOP or an NCI-designated cancer center showed patterns of associations very similar to those for the full study population (Table 3). A total of 503 of these physicians (66.2%) reported that they had referred or enrolled at least one patient in cancer clinical trials in the previous 12 months. Medical and radiation oncologists were more likely than surgeons to participate in clinical trials (80.8% vs 55.2%; P < .001). Also associated with clinical trials participation among physicians with a CCOP or NCI-designated cancer center affiliation was a practice size of six or more physicians compared with one to five physicians (71.2% vs 61.4%; P = .019), practicing in one of five large health maintenance organizations compared with practicing in Los Angeles County (74.6% vs 58.9%; P = .001), teaching medical students or residents compared with no teaching (73.3% vs 57.7%; P < .001), seeing 20 or more lung or colorectal cancer patients per month compared with seeing fewer than five patients (77.4% vs 60.0%; P = .002), and attending weekly tumor board meetings compared with attending meetings quarterly or less frequently (71.0% vs 55.1%; P = .001).

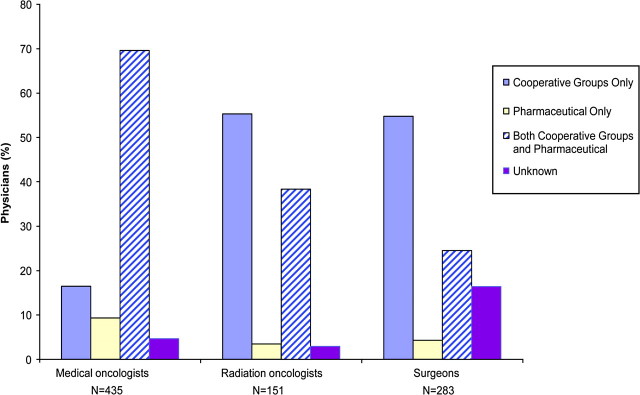

Types of Clinical Trials in Which Specialty Physicians Participate

Among the 869 physicians who referred or enrolled at least one patient in a cancer clinical trial during the previous 12 months, 430 (49.5%) participated in trials sponsored by cooperative groups and in trials sponsored by pharmaceutical companies (Figure 2). However, participation in these trials varied by physician specialty: 69.6% of medical oncologists participated in both trial types compared with 38.3% of radiation oncologists and 24.5% of surgeons. Radiation oncologists and surgeons more often participated only in trials sponsored by cooperative groups compared with medical oncologists. Less than 10% of physicians reported participating only in trials sponsored by pharmaceutical companies.

Figure 2.

Types of clinical trials in which specialty physicians participated (n = 869).

Characteristics of Specialty Physicians With Greater Clinical Trials Involvement

Of the physicians who referred or enrolled at least one patient in a clinical trial during the previous 12 months, characteristics associated with those who referred or enrolled a greater number of patients in multivariate analyses are shown in Table 4. Among the nonsurgical specialists, medical oncologists referred or enrolled 27% more patients compared with radiation oncologists (CR = 1.27, 95% CI = 1.16 to 1.38, P < .001). Nonsurgical specialists reporting income increases as a result of enrolling patients in trials referred or enrolled 20% more patients compared with those reporting no income increases (CR = 1.20, 95% CI = 1.12 to 1.30, P = .001). Other characteristics associated with referring or enrolling more patients in clinical trials were affiliation with an NCI-designated cancer center compared with no such affiliation (CR = 1.30, 95% CI = 1.21 to 1.39, P < .001), being in an office-based group practice compared with being in a hospital-based practice (CR = 1.08, 95% CI = 1.01 to 1.16, P = .038), being in a practice of 11–20 physicians compared with a practice with five or fewer physicians (CR = 1.13, 95% CI = 1.05 to 1.22, P = .035), seeing 20 or more lung or colorectal cancer patients per month compared with seeing fewer than five patients (CR = 1.22, 95% CI = 1.12 to 1.34, P < .001), spending 60 minutes or more with newly diagnosed cancer patients compared with less than 60 minutes (CR = 1.08, 95% CI = 1.02 to 1.15, P = .031), teaching medical students or residents compared with no teaching (CR = 1.12, 95% CI = 1.06 to 1.19, P = .004), and attending weekly tumor board meetings compared with attending quarterly or less frequently (CR = 1.15, 95% CI = 1.01 to 1.31, P < .001). By contrast, medical and radiation oncologists who had not graduated from a US or Canadian medical school referred or enrolled fewer patients in trials compared with those who had (CR = 0.91, 95% CI = 0.86 to 0.97, P = .019) as had medical and radiation oncologists who had participated in either pharmaceutical company–sponsored trials or cooperative group–sponsored trials compared with those who had participated in both types of trials (CR = 0.57, 95% CI = 0.52 to 0.63, P < .001).

Among the surgical specialists, those who identified themselves as thoracic surgeons (CR = 1.48, 95% CI = 1.25 to 1.76), surgical oncologists (CR = 1.74, 95% CI = 1.48 to 2.06), and other surgical subspecialists (CR = 1.60, 95% CI = 1.22 to 2.09) referred or enrolled more patients compared with those who identified themselves as general surgeons (P = .007). Other characteristics associated with surgeons who referred or enrolled more patients in clinical trials were similar to those of medical and radiation oncologists who referred or enrolled more patients in clinical trials, with the following exceptions. Surgeons younger than 60 years referred or enrolled fewer patients compared with those aged 60 years or older (age 50–59 years: CR = 0.75, 95% CI = 0.64 to 0.88, P = .04). Female surgeons referred or enrolled more patients compared with their male counterparts (CR = 1.33, 95% CI = 1.10 to 1.61, P = .029). However, among surgeons, having graduated from a US or Canadian medical school, practice type and size, and the amount of time spent with newly diagnosed cancer patients were not associated with referring or enrolling more patients in clinical trials (P > .1 for each).

Discussion

Low and slow accrual to cancer clinical trials limits the availability of state-of-the-art therapies in routine clinical practice (31). The role of physicians in recruiting patients to clinical trials is pivotal (9,31,32). A committee convened by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) to evaluate the cancer clinical trials system in the United States recently concluded that more physicians need to be encouraged to include trial participation in their clinical practice and that clinical trials participation by investigators in community settings and in academia is needed (33). This study sheds light on the types of specialty physicians who do and do not participate in cancer clinical trials and, in regression modeling, we identify potential points of intervention for increasing physician participation. Using data from CanCORS, a large, multiregional, population-based research initiative, we found that approximately one-half of specialty physicians reported that they had referred or enrolled at least one patient in a cancer clinical trial during the previous year and that physicians differed markedly in their clinical trials participation, with medical oncologists most likely and surgeons least likely to participate by referring or enrolling patients. Most medical oncologists participated in both cooperative group– and pharmaceutical industry–sponsored trials, whereas radiation oncologists and surgeons more often participated only in cooperative group–sponsored trials. Among physicians who reported participating in trials, medical oncologists referred or enrolled more patients in clinical trials compared with radiation oncologists or surgeons. In addition, even among physicians with a CCOP or NCI-designated cancer center affiliation—environments specifically designed to support physicians’ clinical trials involvement—not all participated in trials.

The continued success of the US clinical trials enterprise requires participation from more patients (34–36) and a qualified investigator workforce. However, the number of physician investigators in the United States may be declining (34), and there is expected to be a national shortage of medical oncologists (37,38). A greater patient demand due to an aging population coupled with a provider shortage is likely to place pressure on oncologists to see more patients. If impelled to increase their patient volume, oncologists may reduce their involvement in nonclinical activities, including research (39), and they may have less time during visits for time-consuming discussions with patients about participating in clinical trials. Lack of time and the time demands associated with participation in clinical trials are frequently cited by physicians—who are not specifically reimbursed for counseling patients about clinical trial options (31)—as reasons for not participating in them (4,6,10,14,18). In this study, 88% of medical oncologists, compared with 66% of radiation oncologists and 35% of surgeons, indicated that they had referred or enrolled at least one patient in a clinical trial during the previous year. Our findings showing that a high proportion of medical oncologists already participate in clinical trials are important when considered in context with projections of clinical investigator and oncologist shortages: If such shortages increase physicians’ workload, strategies to ensure that clinical trials remain a priority for physicians will be needed.

Our results demonstrated that physicians’ practice environments are associated with their participation in clinical trials. Physicians with academic appointments (ie, those who taught medical students or residents) or who had practice affiliations with a CCOP or an NCI-designated cancer center were more likely to participate and to refer or enroll more patients compared with physicians who did not have an academic appointment or did not have practice affiliations with a CCOP or an NCI-designated cancer center. More frequent attendance at tumor board meetings was also associated with physician clinical trials involvement. Previous studies have shown that physicians with academic (16,17,40) or cooperative group (40) affiliations have greater clinical trials involvement than those without such affiliations. This study—with its considerably larger sample size, inclusion of multiple specialty types, and multiregional representation—reinforces these earlier findings. Given that a lack of infrastructure to support physicians’ involvement in clinical trials is frequently cited as a barrier to patient accrual to clinical trials (4,5,12,13,15,17,31), our results underscore the positive influence of NCI’s investment in infrastructure to support clinical trials, including the designated cancer centers program, which began in the 1960s, and CCOP, which was established in 1983 to increase the involvement of community physicians in trials (41,42).

Nevertheless, in this study, only two-thirds of physicians with a CCOP or NCI-designated cancer center affiliation reported involvement in clinical trials. Those more likely to participate in a clinical trial were medical or radiation oncologists (vs surgeons), were in larger practices, had academic appointments, saw a higher volume of lung or colorectal cancer patients, and attended weekly tumor board meetings. These associations were similar to those identified for the overall study sample and further reinforce the association between the practice environment and physician participation in clinical trials. Because physicians who are affiliated with a CCOP or an NCI-designated cancer center already practice in an environment that is designed to facilitate clinical research, targeted outreach to physicians with these affiliations who do not participate in clinical trials may be an efficient way of increasing the clinical investigator base and trial enrollment. Closer examination of nonparticipating physicians in these settings might identify incentives that could be used to increase their willingness to participate in clinical trials. The IOM recommendations (33) for restructuring the federal network of cooperative groups could stimulate increased funding and incentives to physicians, which may make participation in clinical trials a priority for these clinicians.

Another strategy to increase physician participation in clinical trials is to foster a culture of research and encourage a professional responsibility to support clinical research within the medical and professional schools that train clinicians (35). Some (35,43–45) have noted the need to reach out to a broader base of clinicians beyond oncologists or those affiliated with research institutions to increase physician participation in clinical trials. The findings of this study reinforce this contention: Although more than one-half of the specialty physicians caring for CanCORS patients were surgeons, only one-third of the surgeons reported participating in clinical trials. Primary care physicians also appear to have very limited involvement in discussing clinical trial participation with their patients who have cancer (46). Patients might be more receptive to participating in clinical trials if more clinicians were willing to talk with them about clinical trials and provide patients with educational materials about trials (35). Better integration of providers with less trial involvement, such as surgeons and radiation oncologists, through establishment of multidisciplinary cancer care teams may be another means of enhancing their clinical trials participation (47,48).

Placing greater emphasis on developing trials that address important research questions that are relevant to current clinical practice may also increase clinicians’ interest in clinical trial participation (47,49). One study (17) found that the limited availability of surgical clinical trials was an obstacle to surgeon participation in trials for breast cancer patients. In our study, surgeons and radiation oncologists participated in fewer different types of trials compared with medical oncologists; participation in more trial types (ie, those sponsored by pharmaceutical companies and by cooperative groups) was associated with referring or enrolling a higher volume of patients. The availability of clinical trials also varies by patient population. For example, research conducted during the 1990s estimated that more than 70% of pediatric cancer patients enroll in clinical trials (50). Although the number of trials that would be needed to achieve a comparable rate in adult populations is unfeasible, future work might assess the specific role that trial availability has on clinician involvement in clinical trials. Clinical trials that include older and sicker patients could be particularly useful to guide treatment decisions, given the uncertainty about whether guideline-recommended treatments are beneficial in these populations (25,51).

Greater use of information technology and improved reimbursement and incentive systems are additional strategies that might increase physician participation in clinical trials. Information technology support, including comprehensive clinical trial databases and electronic health records, are potentially valuable tools that may make it easier for clinicians—especially those not affiliated with research institutions—to identify available trials and eligible patients (34,35,49). Realigning reimbursement and incentive systems to more fully cover the costs associated with clinical trials and reward clinicians for participating in them may also be important for encouraging physician participation in clinical trials (49). Our results showed that financial incentives were associated with physicians’ clinical trials accrual volume, a finding consistent with previous work demonstrating that financial incentives influence physician behavior and quality of care (52,53). However, relatively few physicians in our study reported that their income increased as a result of enrolling patients in clinical trials; further research to evaluate the utility and impact of financial incentives is needed. Moreover, some have argued against using monetary payments to promote physician involvement in clinical trials because of the potential for creating incentives that are not in the patient’s best interests (35).

This study has several limitations. First, the physicians who participated in the survey did not comprise a nationally representative sample, and the clinical trials involvement of respondents may have differed from those who did not respond to the survey. Second, this study is based on physicians’ self-reports of their participation in clinical trials and focused on their personal and practice characteristics. We did not obtain information on physicians’ beliefs about or attitudes toward clinical research or trials, and so could not examine their potential influence on clinical trials participation. Third, our measure of trial participation combined the constructs of patient referral and enrollment. Therefore, we are unable to provide separate estimates of the number of patients referred vs the number enrolled. In surveys, physicians may overestimate the volume of patients they enroll in trials (15,54). We did not have a measure of the physician’s total volume of cancer patients and so were unable to calculate incidence rates for patient referral or enrollment. Although the number of colorectal and lung cancer patients seen by the physician in a typical month was included as an independent variable in our models, this measure may not adequately control for overall patient volume; physicians who see more cancer patients may have greater opportunity to refer or enroll them in trials. Finally, we did not obtain detailed information from physicians about characteristics of their patients. Physicians whose patient population includes a higher concentration of older, sicker patients with advanced-stage cancer might participate less in clinical trials compared with physicians who see a younger healthier patient population because the trial options available for such patients are limited.

The accelerating pace of scientific developments is increasing the number of new therapies that require evaluation in clinical trials. Developing and maintaining a clinical investigator base is essential for a robust clinical trials enterprise but this endeavor is challenged by the time and resources required of clinicians to participate in trials and the projected national shortages of physicians in several disciplines important to cancer trials (37,55,56). NCI is addressing some of these issues through implementation of recommendations by the National Cancer Advisory Board Clinical Trials Working Group (49) and consideration of the recently released IOM report (33). NCI also continues its substantial investment in clinical trials infrastructure by expanding the NCI-designated cancer centers and CCOPs and implementing the National Community Cancer Centers Program, a pilot project to increase access to state-of-the-art cancer care in nonresearch settings (57). Realizing the full potential of clinical research in the 21st century will require these and other efforts to address the complex factors that shape cancer care in the United States. More research is needed to better understand clinician attitudes toward clinical research and to examine specific features of practice infrastructure—including availability of support staff, electronic health records, reimbursement, and clinical trial databases—that facilitate or hinder physician participation in clinical trials. As noted in the IOM report (33), “the inability to recruit, train, and retain a sufficient number of talented clinical investigators will ultimately compromise the ability to conduct cancer clinical trials in the U.S., to the detriment of the U.S. biomedical research enterprise and to patients.” Continued monitoring of physician participation in cancer clinical trials will be essential.

Funding

This work of the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) consortium was supported by grants from the NCI to the Statistical Coordinating Center (U01 CA093344) PI: David Harrington and the NCI-supported Primary Data Collection and Research Centers (Dana Farber Cancer Institute/Cancer Research Network U01 CA093332 PI: Jane Weeks, Harvard Medical School/Northern California Cancer Center U01 CA093324 PI: John Ayanian, RAND/UCLA U01 CA093348 PI: Katherine Kahn, University of Alabama at Birmingham U01 CA093329 PI: Mona Fouad, University of Iowa U01 CA093339 PI: Robert Wallace, University of North Carolina U01 CA093326, PI: Robert Sandler) and by a Department of Veteran’s Affairs grant to the Durham VA Medical Center CRS 02-164 PI: Dawn Provenzale.

Footnotes

The authors take full responsibility for the analysis and interpretation of the data, the writing of the article, and the decision to submit the article for publication.

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute. NCI Features: Clinical Trials and You. http://www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials. Accessed December 22, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lara PN, Higdon R, Lim N, et al. Prospective evaluation of cancer clinical trial accrual patterns: identifying potential barriers to enrollment. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(6):1728–1733. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.6.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sateren WB, Trimble EL, Abrams J, et al. How sociodemographics, presence of oncology specialists, and hospital cancer programs affect accrual to cancer treatment trials. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(8):2109–2117. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ross S, Grant A, Counsell C, Gillespie W, Russell I, Prescott R. Barriers to participation in randomized controlled trials: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52(12):1143–1156. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pinto HA, McCaskill-Stevens W, Wolfe P, Marcus AC. Physician perspectives on increasing minorities in cancer clinical trials: an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) initiative. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10(8 suppl):S78–S84. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00191-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fallowfield L, Ratcliffe D, Souhami R. Clinicians’ attitudes to clinical trials of cancer therapy. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33(13):2221–2229. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)00253-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mills EJ, Seely D, Rachlis B, et al. Barriers to participation in clinical trials of cancer: a meta-analysis and systematic review of patient-reported factors. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(2):141–148. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70576-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldberg KB. Physician attitudes and trial enrollment. Cancer Lett. 2007;33(22):5–6. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howerton MW, Gibbons MC, Baffi CR, et al. Provider roles in the recruitment of underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials. Cancer. 2007;109(3):465–476. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCaskell-Stevens W, Pinto H, Marcus AC, et al. Recruiting minority cancer patients into cancer clinical trials: a pilot project involving the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group and the National Medical Association. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(3):1029–1039. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.3.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kornblith AB, Kemeny M, Peterson BL, et al. Survey of oncologists’ perceptions of barriers to accrual of older patients with breast carcinoma to clinical trials. Cancer. 2002;95(5):989–996. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hudson SV, Momperousse D, Leventhal H. Physician perspectives on cancer clinical trials and barriers to minority recruitment. Cancer Control. 2005;12(suppl 2):93–96. doi: 10.1177/1073274805012004S14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leitch AM, Beitsch PD, McCall LM, et al. Patterns of participation and successful patient recruitment to American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z0010, a phase II trial for patients with early-stage breast cancer. Am J Surg. 2005;190(4):539–542. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen TT, Somkin CP, Ma Y. Participation of Asian-American women in cancer chemoprevention research: physician perspectives. Cancer. 2005;104(12 suppl):3006–3014. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Somkin CP, Altschuler A, Ackerson L, et al. Organizational barriers to physician participation in cancer clinical trials. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11(7):413–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meropol NJ, Buzaglo JS, Millard J. Barriers to clinical trial participation as perceived by oncologists and patients. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2007;5(8):655–664. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2007.0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schroen AT, Brenin DR. Clinical trial priorities among surgeons caring for breast cancer patients. Am J Surg. 2008;195(4):474–480. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benson AB, Pregler JP, Bean JA, Rademaker AW, Eshler B, Anderson K. Oncologists’ reluctance to accrue patients onto clinical trials: an Illinois Cancer Center study. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9(11):2067–2075. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.11.2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Cancer Institute. Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium. http://healthservices.cancer.gov/cancors/. Accessed December 22, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ayanian JZ, Chrischilles EA, Fletcher RH, et al. Understanding cancer treatment and outcome: the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(15):2992–2996. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Catalano P. Representativeness of CanCORS participants relative to Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) cancer registries. Paper presented at Academy Health Annual Research meeting; June 8, 2008; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andersen R, Aday LA. Access to medical care in the U.S.: realized and potential. Med Care. 1978;16(6):533–546. doi: 10.1097/00005650-197807000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andersen RM. Revisting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phillips KA, Morrison KR, Andersen R, Aday LA. Understanding the context of healthcare utilization: assessing environmental and provider-related variables in the behavioral model of utilization. Health Serv Res. 1998;33(3, pt 1):571–596. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keating NL, Landrum MB, Klabunde CN, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer: do physicians agree about the importance of patient age and comorbidity? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15):2532–2537. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.9434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Little RJ, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis With Missing Data. New York, NY: Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27.He Y, Zaslavsky AM, Harrington DP, Catalano P, Landrum MB. Multiple imputation in a large-scale complex survey: a practical guide. Stat Methods Med Res. 2010 Dec;19(6):653–70. doi: 10.1177/0962280208101273. Epub 2009 Aug 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Korn E, Graubard B. Analysis of Health Surveys. New York, NY: Wiley; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Graubard BI, Korn EL. Predictive margins with survey data. Biometrics. 1999;55(2):652–659. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lambert D. Zero-inflated Poisson regression, with an application to defects in manufacturing. Technometrics. 1992;34(1):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siminoff LA. Why learning to communicate with our patients is so important: using communication to enhance accrual to cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(16):2614–2615. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Umutyan A, Chiechi C, Beckett LA, et al. Overcoming barriers to cancer clinical trial accrual: impact of a mass media campaign. Cancer. 2008;112(1):212–219. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Institute of Medicine. A National Cancer Clinical Trials System for the 21st Century: Reinvigorating the NCI Cooperative Group Program. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sung NS, Crowley WF, Jr, Genel M, et al. Central challenges facing the national clinical research enterprise. JAMA. 2003;289(10):1305–1306. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.10.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Avins AL, Goldberg H. Creating a culture of research. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007;28(4):557–562. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kolata G. Forty years’ war: lack of study volunteers may hobble cancer fight. New York Times. August 3, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Erickson C, Salsberg E, Forte G, Bruinooge S, Goldstein M. Future supply and demand for oncologists: challenges to assuring access to oncology services. J Oncol Pract. 2007;3(12):79–86. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0723601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Warren JL, Mariotto AB, Meekens A, Topor M, Brown ML. Current and future utilization of services from medical oncologists. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(19):3242–3247. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.6357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.American Society of Clinical Oncology. Status of the medical oncology workforce. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(9):2612–2621. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.9.2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Siminoff LA, Zhang A, Colabianchi N, Sturm CM, Shen Q. Factors that predict the referral of breast cancer patients onto clinical trials by their surgeons and medical oncologists. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(6):1203–1211. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.6.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.National Cancer Institute. Cancer Centers Program. http://cancercenters.cancer.gov. Accessed December 22, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 42.National Cancer Institute. Division of Cancer Prevention. Community Clinical Oncology Program (CCOP) http://prevention.cancer.gov/programs-resources/programs/ccop. Accessed December 22, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Academy for Educational Development. Review of best practices for participant recruitment into clinical trials. 2007 Report prepared for the National Cancer Institute under contract GS-00F-0007M, order no. 265-FQ-613301, task C1. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sherwood PR, Given BA, Scholnik A, Given CW. To refer or not to refer: factors that affect primary care provider referral of patients with cancer to clinical treatment trials. J Cancer Educ. 2004;19(1):58–65. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce1901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McKinney MM, Weiner BJ, Carpenter WR. Building community capacity to participate in cancer prevention research. Cancer Control. 2006;13(4):295–302. doi: 10.1177/107327480601300407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klabunde CN, Ambs A, Keating NL, et al. The role of primary care physicians in cancer care. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(9):1029–1036. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1058-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Curran WJ, Schiller JH, Wolkin AC, Comis RL. Addressing the current challenges of non-small-cell lung cancer clinical trial accrual. Clin Lung Cancer. 2008;9(4):222–226. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2008.n.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Twelves CJ, Thomson CS, Young J, Gould A. Entry into clinical trials in breast cancer: the importance of specialist teams. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34(7):1004–1007. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)10126-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.National Cancer Institute. Report of the Clinical Trials Working Group of the National Cancer Advisory Board: restructuring the national cancer clinical trials enterprise. 2005 http://restructuringtrials.cancer.gov/file/ctwg-reports.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tejeda HA, Green SB, Trimble EL, et al. Representation of African-Americans, Hispanics, and whites in National Cancer Institute cancer treatment trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88(12):812–816. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.12.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rogers SO, Jr, Gray SW, Landrum MB, et al. Variations in surgeon treatment recommendations for lobectomy in early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer by patient age and comorbidity. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(6):1581–1588. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0946-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hillman AL, Pauly MV, Kerstein JJ. How do financial incentives affect physicians’ clinical decisions and the financial performance of health maintenance organizations? N Engl J Med. 1989;321(2):86–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198907133210205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Petersen LA, Woodard LD, Urech T, Daw C, Sookanan S. Does pay-for-performance improve the quality of health care? Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(4):265–272. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-4-200608150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Taylor KM, Feldstein ML, Skeel RT, Pandya KJ, Ng P, Carbone P. Fundamental dilemmas of the randomized clinical trial process: results of a survey of the 1,737 Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group investigators. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12(9):1796–1805. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.9.1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Voelker R. Experts say projected surgeon shortage a “looming crisis” for patient care. JAMA. 2009;302(14):1520–1521. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bodenheimer T. Primary care: will it survive? N Engl J Med. 2006;355(9):861–864. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Clauser SB, Johnson MR, O’Brien DM, Beveridge JM, Fennell ML, Kaluzny AD. Improving clinical research and cancer care delivery in community settings: evaluating the NCI community cancer centers program. Implement Sci. 2009;4:63. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]