Abstract

The breast-plate plumage of male Lawes' parotia (Parotia lawesii) produces dramatic colour changes when this bird of paradise displays on its forest-floor lek. We show that this effect is achieved not solely by the iridescence—that is an angular-dependent spectral shift of the reflected light—which is inherent in structural coloration, but is based on a unique anatomical modification of the breast-feather barbule. The barbules have a segmental structure, and in common with many other iridescent feathers, they contain stacked melanin rodlets surrounded by a keratin film. The unique property of the parotia barbules is their boomerang-like cross section. This allows each barbule to work as three coloured mirrors: a yellow-orange reflector in the plane of the feather, and two symmetrically positioned bluish reflectors at respective angles of about 30°. Movement during the parotia's courtship displays thereby achieves much larger and more abrupt colour changes than is possible with ordinary iridescent plumage. To our knowledge, this is the first example of multiple thin film or multi-layer reflectors incorporated in a single structure (engineered or biological). It nicely illustrates how subtle modification of the basic feather structure can achieve novel visual effects. The fact that the parotia's breast feathers seem to be specifically adapted to give much stronger colour changes than normal structural coloration implies that colour change is important in their courtship display.

Keywords: Lawes' parotia, iridescence, feather reflectance, multi-layers, thin film, scattering

1. Introduction

Bird feathers have two main mechanisms of structural coloration: either a spongy keratin matrix with air spaces or multi-layers created by regularly arranged melanin rodlets in a keratin matrix [1–3]. As air, keratin and melanin have different refractive indexes, light is reflected at the interfaces [4]. With keratin sponges, the spacing of the air–keratin interfaces is more or less independent of orientation, so that the reflection is diffuse, rather than directional [5–7]. This diffuse reflection means that the visual appearance of keratin sponges tends to resemble ordinary pigmented materials, but birds use them to create blues and greens that are difficult to make with plumage pigments [8]. Feathers with a thin-film cortex and/or regularly arranged melanin rodlets give directional (mirror-like) reflections, which are described by multi-layer theory [9–12]. Appropriate spacing and orientation of the elements produce intensely saturated colours and directional effects, which are not achieved by ordinary pigments [5,10]. Multi-layer reflectors are inherently iridescent—that is, the wavelength (approximately hue) of the reflected light varies with the viewing geometry [10].

The male bird of paradise Lawes' parotia (Parotia lawesii; figure 1) displays brilliant iridescent breast feathers to attract females [13–15]. Iridescence emerges from the barbules, which, in common many other feathers, contain orderly arrays of melanin rodlets embedded in a keratin matrix [1,16]. However, whereas in cross-section barbules generally have a more or less flattened oval shape, sometimes with slight bends and turns (e.g. [1,17]), the parotia barbules have a unique boomerang-like shape [1,16]. Here, we show that the parotia breast feathers are (as far as we know) uniquely modified to greatly enhance the colour changes when the males perform their exhilarating ballerina dance on the forest floor [15]. Each feather barbule appears to incorporate three separate coloured mirrors that reflect light in different directions. This allows abrupt switches between yellow, blue and black. These observations exemplify how a modification of the basic feather anatomy can produce a new visual effect, and give insight into the evolution and function of structural coloration in avian displays.

Figure 1.

Painting of Parotia lawesii by Richard Bowdler Sharpe (upper, male; lower, female) (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Parotia_lawesii_by_Bowdler_Sharpe.jpg). Frith & Beehler [29] also illustrate the bird. The Macaulay library has film taken by E. Scholes (http://macaulaylibrary.org/video/45933).

2. Material and methods

We photographed a male Lawes' parotia from labelled skins in the collection of the Queensland Museum, Brisbane (figure 2a,b). The same museum provided four breast feathers for study with conventional light microscopy (epi-illumination as well as transmitted light) and with transmission electron microscopy. We examined the feathers with an imaging scatterometer ([18]; see also [19]), which yields images of the light reflected into a 180° hemisphere by locally illuminated feather barbules. Furthermore, we measured the feather reflectance spectra from different directions in a plane perpendicular to the barbule axes with a bifurcated fibre-optic probe. The instrument comprised six light guides, delivering light from a halogen-deuterium lamp to the feather. These illuminating light guides collectively surrounded a central fibre that acted as a collector of scattered light and which delivered it to a photodiode-array-spectrometer (Avantes, AvaSpec-2048-2). A white diffusing reflectance standard (Avantes WS-2) served as the reference. In addition, we measured the feather reflectance with an angular reflectance measurement set-up consisting of two fibres rotating, independently from each other, around the same axis in a plane containing the barbule axis [5]. One fibre acted as the light source, delivering light from a xenon lamp, and illuminated an area with a diameter approximately 4 mm; the other fibre captured the reflected light and delivered it to the spectrometer. The two fibres were symmetrically rotated with respect to the normal to the feather plane.

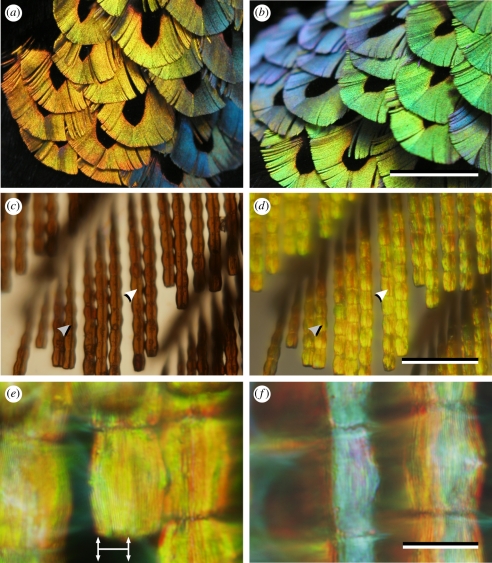

Figure 2.

The colours of male Lawes' parotia breast feathers. (a) With an approximately fronto-parallel view and illumination behind the observer the reflection is mainly yellow-orange. (b) An oblique view yields blue and green reflections. (c) A transmitted-light microscope photograph of a few barbs shows brown, segmented barbules with a central dark line, indicated by arrows. (d) The same barbs photographed with epi-illumination show yellow barbules, also with a central dark line, indicated as in (c). (e) At high magnification the cushion-shaped, yellow barbule segments show longitudinal stripes separated by 0.5–0.6 µm (approx. 15 lines are visible over a span of 8 µm, as indicated by the horizontal line with vertical arrows). (f) Slight rotation of the barbules yields a blue reflection from one side of each segment. Scale bars, (a,b) 1 cm; (c,d) 100 µm; (e,f) 20 µm.

3. Results

The breast-plate feathers of male Lawes' parotia have a conventional structure; barbs emanate from a central rachis, and barbules emanate from the barbs. Each feather has a central region of black barbs, which is surrounded by a broad margin of brilliant coloured barbs (figure 2a,b). Viewed from above, the coloured barbules appear as a row of cushion-shaped segments (approx. 20 × 25 µm2; figure 2c–f). With the feather normal to the line of sight and illuminated with a co-axial beam (i.e. as if viewed face-on with the sun behind the viewer) the segments are coloured yellow-orange (figure 2d,e).

In transmitted light microscopy, the barbule segments are brown, as is typical of melanin pigmentation [5], and feature a prominent axial line (figure 2c), which is also seen in epi-illumination (figure 2d). High magnification (figure 2e) shows a longitudinal grating of dark lines separated by 0.5–0.6 µm. There are 12–15 lines over the 8 µm horizontal section arrowed in figure 2e. When the barbule is rotated, a bluish colour appears on one or other side of the barbule segments (figure 2f).

For further study of the optical properties of the feather, we used transmission electron microscopy. An approximately longitudinal section (figure 3a) shows a characteristic barbule, about 5 µm thick. The barbule has a clear (presumably) keratin cortex about 250–300 nm thick, which surrounds approximately 25 layers of pigmented rodlets, with a diameter approximately 60–90 nm, set in a keratin matrix. The pigment layers are separated by approximately 200 nm and are approximately perpendicular to the symmetry plane, but slightly curved. In the cross section, the barbule has a distinctive, boomerang-like shape: the upper surface consists of two flattish planes, width approximately 8 µm, separated by an angle of about 120°. About 15 rodlet planes terminate on the upper surface of each side of the barbule (figure 3b).

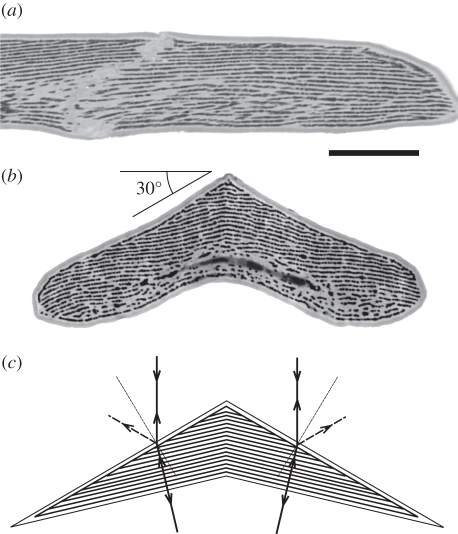

Figure 3.

Transmission electron micrographs of a breast feather barbule. (a) A longitudinal section shows that melanin rodlets form parallel layers in a keratin matrix; scale bar, 5 µm. (b) A transverse section shows the ridged structure of the top surface of the barbule with two faces enclosing an angle of about 120° (compare [16], fig. 5 and [1], fig. 23). About 15 melanin layers border the left-hand slope over a span of 8 µm (compare figure 2e). (c) Diagram of the barbule cross section, assuming an effective refractive index 1.56. When the multi-layer inside the barbule is tilted at an angle of 11.3° with respect to the horizontal plane on both sides of the symmetry plane, a light beam incident normal to the horizontal plane hits the multi-layers normally, and thus will be reflected back along the line of incidence. Part of the incident light is, however, reflected at the surface. The angle between the incident and reflected beam then is 60°, because of the 30° slant of the upper surface of the barbule segments.

The ‘roof-line’ along the upper surface of the barbule segments (figure 3b) immediately explains the axial line seen on the barbules with light microscopy (figure 2c,d). Also, the number of the melanin layers abutting the sides of the upper surface in figure 3b corresponds with the number of the dark lines seen in the barbule segments with the light microscope (figure 2e). The implication is that the entire barbule surface appears yellow-orange owing to optical interference in the pigment layers within the barbule segments as pictured in the diagram of figure 3c. A light ray parallel to the symmetry plane incident at the 30° slanted top surfaces is refracted with an angle 18.7°, assuming that the dominant medium of the barbule segment is keratin with an effective refractive index of 1.56 (e.g. [11]). The refracted ray will hit the multi-layer inside the barbule normally when the multi-layer is tilted over an angle of 11.3°. The tilted multi-layers as seen in figure 3b may, therefore, function to counteract angular spreading of the reflected light.

In addition to the refraction, the incident light will be partially reflected at the surface. Apparently, the layering of the barbule cortex selectively favours the reflection of blue light, as was observed when rotating the barbules (figure 2f). With incident light in the symmetry plane, the direction of the reflected light beams from the two surface sides will then be −60° and +60° (figure 3c).

To investigate the feather's optical properties further, we placed an isolated barb, glued to a pipette, in our imaging scatterometer [18] and illuminated an approximately 200 µm diameter spot (figure 4a) with a beam of white light normal to the feather surface (figure 4b). The diagram of figure 4b illustrates how the barb reflects light from the normal incident beam into a hemisphere (the red circles indicate reflection angles of 5°, 30°, 60° and 90°). The distribution of scattered light projected into a polar coordinate system yields the far-field scattering pattern (figure 4c,d; the red circles in the polar plot represent the same reflection angles as the circles of figure 4b). With illumination normal to the barb ‘face’ (figure 4c), the barbules reflect yellow-orange light approximately along the direction of the illumination (as for a fronto-parallel reflector), while blue-green light is reflected in two directions about 60° to the normal direction (cf. figures 3c and 4b). Rotating the barb by about 10° results in an angular shift of the scattering pattern (figure 4d), and the colours of the two reflected side beams change in opposite spectral directions; that is, one side beam becomes greener, the other more violet. Similarly, if less obviously, the colour of the central, yellow-orange beam also changes, with long-wavelength (redder) or short-wavelength (greener) yellow coloration according to the direction of reflection (figure 4d). These observations are entirely consistent with the barb behaving as a set of three multi-layer mirrors (figure 4e,f; [5,10]), where a decrease (increase) in the angle of incidence shifts the reflection to longer (shorter) wavelengths.

Figure 4.

Imaging scatterometry that shows how a single barbule reflects light from a point source into a hemisphere. The barbule acts as three separate coloured mirrors, each of which reflects in a different direction. (a) A 200 µm diameter spot is illuminated with a narrow beam of white light; scale bar, 100 µm. (b) Diagram of how normally incident light is reflected. Yellow-orange light is reflected about normally, and bluish light is reflected in two opposite directions with angles of 60°; cf. figure 3c. (c) Polar scatterograms, showing the angular distribution of the scattered light by the barbule with about normal illumination. The red circles indicate inclination angles of 5°, 30°, 60° and 90°. The central black spot (approximating the circle with polar angle 5°) is due to the axial hole in the ellipsoidal mirror of the scatterometer [18]. (d) The angular distribution of the scattered light from the barbule rotated over a 10° angle. (e,f) Diagrams explaining the polar scatterograms of figure 4c,d.

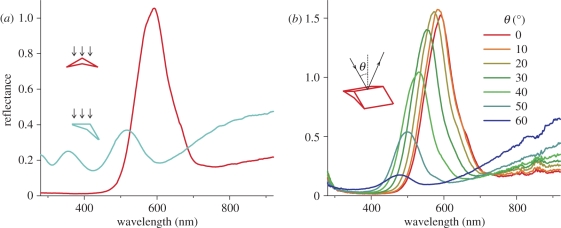

The light reflected by the different mirrors is coloured quite differently. To investigate the spectra of the light reflected by the breast feathers of the parotia, we applied two different spectrophotometric methods. Firstly, we used a bifurcated fibre-optic probe, which measures a small area (diameter 1–2 mm). It gave a narrow-band spectrum with a peak at about 600 nm when the probe was normal to the feather surface (figure 5a). The peak moved to shorter wavelengths upon rotation of the feather around the barbule axis. A bluish reflectance, peaking at about 500 nm, emerged at an angle of about 30° (figure 5a). Secondly, we used a pair of optical fibres that could be rotated independently around the same axis, one acting as the light source, the other as the light collector. The reflectance of a feather with the barbule symmetry axis perpendicular to the rotation axis was measured as a function of the angle of light incidence. The fibre delivering the light was rotated in steps of 10°. To obtain the maximal reflectance, the fibre capturing the reflected light had to be rotated over the same angle but in the opposite direction. The peak of the resulting spectra shifted progressively towards shorter wavelengths and the reflectance amplitude decreased with larger angles of incidence (figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Reflectance spectra of a Lawes' parotia breast feather. (a) Measurement with the bifurcated probe normal to the feather plane (0°) and with the feather rotated through an angle of φ = 30° along the longitudinal axis of the barbule (cf. figure 2a showing the yellow-orange and bluish reflections). (b) Measurement with two rotating fibres where one fibre delivered light from an angle of incidence θ in the longitudinal symmetry plane of the barbule and the other fibre collected the light reflected into the mirror direction (cf. figure 2b showing the green reflections).

4. Discussion

By incorporating multiple tuned mirrors in a single barbule, Lawes' parotia's breast feathers produce strongly different colours. Melanin multi-layers within the barbules give yellow-orange reflections, while the cortex acts as an enveloping thin film system producing bluish side beams. Coloration by melanin multi-layers is widely used in feathers [1,10,20] and elsewhere in the animal kingdom, for example, in beetles [21–24]. Here, reflectance is well described by classical multi-layer theory for a stack of layers with alternating low and high refractive index. Notably, increasing the angle of illumination shifts the reflectance spectrum to shorter wavelengths, together with a reflectance increase and a distinct polarization of the reflected light that is extreme at a (generalized) Brewster's angle. These effects were experimentally demonstrated and quantitatively described for the elytra of the jewel beetle Chrysochroa fulgidissima [24]. Parotia breast feathers share some, but certainly not all, of these features. As expected for a multi-layer reflector, the peak wavelength of the barbule reflectance decreases with increasing angle of incidence (figure 5b). The interference condition predicts a reflectance peak for normal illumination at λmax = 2(nldl + nhdh), where nl and nh are the low and high refractive index values, and dl and dh are the corresponding thicknesses of the alternating layers (e.g. [10,20]). The distance of the layers inside the parotia barbules was found to be about 200 nm. With an effective layer thickness of dh = 50 nm of the melanin layers and refractive indices nl = 1.56 of the keratin [11] and nh = 1.69 of the melanin [24], the expected peak wavelength is λmax = 637 nm, somewhat higher than the measured 600 nm (figure 5a). More at variance with the expectations is the finding that the reflectance amplitude also decreases with increasing angle of incidence, which is opposite to the usual amplitude increase with increasing angle. Strictly, the latter effect is true only for TE-polarized light, because the amplitude of TM-polarized light decreases with increasing angle of incidence up to the Brewster's angle; only above that value does the amplitude increase [24]. However, for unpolarized light, which we applied in the experiment of figure 5b, the reflection is dominated by TE-light so that the reflectance of a classical multi-layer for unpolarized light increases with increasing angle of incidence. Furthermore, although preliminary experiments showed that the light reflected by the parotia feathers does indeed become polarized with increasing angle of incidence, the observed phenomena deviate distinctly from those expected for a classical multi-layer. The reason most probably is that a roof of thin-film keratin layers covers the melanin multi-layer (figure 3), which will strongly affect the reflectance. Further study of the intricate optics of the parotia barbules is needed for a detailed, quantitative understanding of the feather reflectance.

The fact that with approximately normal illumination two bluish side beams are reflected at angles of approximately −60° and +60° strongly suggests that they are produced by the sloping upper surfaces of the barbule, which are approximately −30° and +30° to the plane of the feather blade (figure 3b). The air/keratin/melanin interface of the barbule cortex presumably works as a thin-layer reflector—like oil on water. Many birds employ such thin-film reflectors to produce an iridescent ‘gloss’ (e.g. satin bowerbirds [25]; rock dove [26]; blue-back grassquit [11]).

As far as we know the combination of two types of interference reflector within a single feather is unique to the parotia breast-plate plumage. The boomerang-shaped cross section of the barbules has been observed before in the western parotia, Parotia sefilata ([16]; see also [1]), but the optical effect was overlooked. Somewhat similar dual coloration effects are achieved by the highly curved multi-layers of the wing scales of the emerald swallowtail butterfly, Papilio palinurus [27] and the Madagascan sunset moth, Chrysiridia rhipheus [28], but there the structure produces polarization-sensitive colour mixing rather than abrupt hue-shifts.

(a). The evolution of iridescence and role of colour change in avian visual displays

Before mating, parotia females make multiple visits to courts, where the males use six main types of display, which include a range of movements described as ‘bobs’, ‘bows’, ‘dances’ and so-forth [14]. Frith & Beehler [29] comment that the courtship display of Lawes' parotia is ‘a ritualized set of danced steps and movements accompanied by intricate feather movements as complex (as that of) any bird’; see [15], notably figs 14 and 15; and movie at http://macaulaylibrary.org/video/45933).

The parotia feather beautifully illustrates the versatility of feathers as optical devices [3], but what does it say about the evolution and function of iridescent coloration in displays? Multi-layer structural coloration is commonly associated with display plumage [30], the peacock being the best-known case [12,31], and for human observers the iridescence is part of its beauty [32,33]. Nonetheless, in natural viewing conditions, ordinary multi-layer structures often give a rather small wavelength (or ‘hue’) shift in reflectance [5]. So far as we know there are no direct tests of how birds respond to different ‘components’ of the complex optical effects that are produced by structural colours [31], which include saturated, strongly directional and multi-peaked reflectance spectra, but it seems that the parotia's breast plumage is specifically adapted to produce hue-shifts. It is difficult to be specific about the visual effects, but the fact that the feather seems to be engineered for changes in the angle between the feather and the viewer to give much larger chromatic change than is usual for iridescent plumage [5] suggests that hue change is important [13,14,29]. It would be interesting to know what information the colour changes give to the female, and how they interact with the elaborate movements that characterize the parotia's display [14,32,34].

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the AFOSR/EOARD (grant FA8655-08-1-3012, to DGS), the Royal Society (to D.O.) and the Australian Research Council (to N.J.M. and D.O.). We thank the Queensland Museum (Brisbane) for access to their collection. Clifford and Dawn Frith were instrumental in initiating this research. Lydia Mäthger and Julian Thorpe did the electron microscopy.

References

- 1.Durrer H. 1977. Schillerfarben der vogelfeder als evolutionsproblem. Denkschr. Schweiz. Naturforsch. Ges. 91, 1–126 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dyck J. 1971. Structure and colour-production of the blue barbs of Agapornis roseicollis and Cotinga maynana. Z. Zellforsch. 115, 17–29 10.1007/BF00330211 (doi:10.1007/BF00330211) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prum R. O. 2006. Anatomy, physics, and evolution of avian structural colors. In Bird coloration. Mechanisms and measurements, vol. I (eds Hill G. E., McGraw K. J.), pp. 295–353 Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kinoshita S., Yoshioka S., Miyazaki J. 2008. Physics of structural colors. Rep. Prog. Phys. 71, 076401. 10.1088/0034-4885/71/7/076401 (doi:10.1088/0034-4885/71/7/076401) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osorio D., Ham A. D. 2002. Spectral reflectance and directional properties of structural coloration in bird plumage. J. Exp. Biol. 205, 2017–2027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prum R. O., Dufresne E. R., Quinn T., Waters K. 2009. Development of colour-producing β-keratin nanostructures in avian feather barbs. J. R. Soc. Interface 6, S253–S265 10.1098/rsif.2008.0466.focus (doi:10.1098/rsif.2008.0466.focus) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prum R. O., Torres R., Williamson S., Dyck J. 1999. Two-dimensional Fourier analysis of the spongy medullary keratin of structurally coloured feather barbs. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 266, 13–22 10.1098/rspb.1999.0598 (doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0598) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGraw K. J. 2006. The mechanics of uncommon colors in birds: pterins, porphyrins, and psittacofulvins. In Bird coloration. Mechanisms and measurements, vol. I (eds Hill G. E., McGraw K. J.), pp. 354–398 Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doucet S. M., Shawkey M. D., Hill G. E., Montgomerie R. 2006. Iridescent plumage in satin bowerbirds: structure, mechanisms and nanostructural predictors of individual variation in colour. J. Exp. Biol. 209, 380–390 10.1242/jeb.01988 (doi:10.1242/jeb.01988) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Land M. F. 1972. The physics and biology of animal reflectors. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 24, 77–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maia R., Caetano J. V. O., Bao S. N., Macedo R. H. 2009. Iridescent structural colour production in male blue-black grassquit feather barbules: the role of keratin and melanin. J. R. Soc. Interface 6, S203–S211 10.1098/rsif.2008.0460.focus (doi:10.1098/rsif.2008.0460.focus) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zi J., Yu X. D., Li Y. Z., Hu X. H., Xu C., Wang X. J., Liu X. H., Fu R. T. 2003. Coloration strategies in peacock feathers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 12 576–12 578 10.1073/pnas.2133313100 (doi:10.1073/pnas.2133313100) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frith C. B., Frith D. W. 1981. Displays of Lawes's parotia, Parotia lawesii (Paradisaeidae), with reference to those of congeneric species and their evolution. Emu 83, 227–238 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pruett-Jones S. G., Pruett-Jones M. A. 1990. Sexual selection through female choice in Lawes' parotia, a lek-mating bird of paradise. Evolution 44, 486–501 10.2307/2409431 (doi:10.2307/2409431) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scholes E. 2008. Structure and composition of the courtship phenotype in the bird of paradise Parotia lawesii (Aves: Paradisaeidae). Zoology 111, 260–278 10.1016/j.zool.2007.07.012 (doi:10.1016/j.zool.2007.07.012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dorst J., Gastaldi G., Hagège R., Jacquemart J. 1974. Différents aspects des barbules de quelques Paradisaeidés sur coupes en microscopie électronique. Relations avec les phénomènes d'interférences. C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris 278, 285–290 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Durrer H., Villiger W. 1970. Schillerradien des goldkuckucks (Chrysococcyx cupreus (Shaw)) im elektronenmikroskop. Z. Zellforsch. 109, 407–413 10.1007/BF02226912 (doi:10.1007/BF02226912) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stavenga D. G., Leertouwer H. L., Pirih P., Wehling M. F. 2009. Imaging scatterometry of butterfly wing scales. Opt. Express 17, 193–202 10.1364/OE.17.000193 (doi:10.1364/OE.17.000193) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vukusic P., Stavenga D. G. 2009. Physical methods for investigating structural colours in biological systems. J. R. Soc. Interface 6(Suppl. 2), S133–S148 10.1098/rsif.2008.0386.focus (doi:10.1098/rsif.2008.0386.focus) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kinoshita S. 2008. Structural colors in the realm of nature. Singapore, Singapore: World Scientific [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hariyama T., Hironaka M., Takaku Y., Horiguchi H., Stavenga D. G. 2005. The leaf beetle, the jewel beetle, and the damselfly; insects with a multilayered show case. In Structural color in biological systems—principles and applications (eds Kinoshita S., Yoshioka S.), pp. 153–176 Osaka, Japan: Osaka University Press [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noyes J. A., Vukusic P., Hooper I. R. 2007. Experimental method for reliably establishing the refractive index of buprestid beetle exocuticle. Opt. Express 15, 4351–4358 10.1364/OE.15.004351 (doi:10.1364/OE.15.004351) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parker A., Mckenzie D., Large M. 1998. Multilayer reflectors in animals using green and gold beetles as contrasting examples. J. Exp. Biol. 201, 1307–1313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stavenga D. G., Wilts B. D., Leertouwer H. L., Hariyama T. 2011. Polarized iridescence of the multilayered elytra of the Japanese jewel beetle, Chrysochroa fulgidissima. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 366 10.1098/rstb.2010.0197 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0197) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doucet S. M., Montgomerie R. 2003. Multiple sexual ornaments in satin bowerbirds: ultraviolet plumage and bowers signal different aspects of male quality. Behav. Ecol. 14, 503–509 10.1093/beheco/arg035 (doi:10.1093/beheco/arg035) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoshioka S., Nakamura E., Kinoshita S. 2007. Origin of two-color iridescence in rock dove's feather. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 76, 013801. 10.1364/OE.15.002691 (doi:10.1364/OE.15.002691) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vukusic P., Sambles R., Lawrence C., Wakely G. 2001. Sculpted-multilayer optical effects in two species of Papilio butterfly. Appl. Opt. 40, 1116–1125 10.1364/AO.40.001116 (doi:10.1364/AO.40.001116) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoshioka S., Kinoshita S. 2007. Polarization-sensitive color mixing in the wing of the Madagascan sunset moth. Opt. Express 15, 2691–2701 10.1364/OE.15.002691 (doi:10.1364/OE.15.002691) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frith C. B., Beehler B. M. 1998. The birds of paradise. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hausmann F., Arnold K. E., Marshall N. J., Owens I. P. F. 2003. UV signals in birds are special. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 270, 61–67 10.1098/rspb.2002.2200 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.2200) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loyau A., Gomez D., Moureau B. T., Théry M., Hart N. S., Saint Jalme M., Bennett A. T. D., Sorci G. 2007. Iridescent structurally based coloration of eyespots correlates with mating success in the peacock. Behav. Ecol. 18, 1123–1131 10.1093/beheco/arm088 (doi:10.1093/beheco/arm088) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doucet S. M., Meadows M. G. 2009. Iridescence: a functional perspective. J. R. Soc. Interface 6, S115–S132 10.1098/rsif.2008.0395 (doi:10.1098/rsif.2008.0395) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meadows M. G., Butler M. W., Morehouse N. I., Taylor L. A., Toomey M. B., McGraw K. J., Rutowski R. L. 2009. Iridescence: views from many angles. J. R. Soc. Interface 6, S107–S113 10.1098/rsif.2009.0013.focus (doi:10.1098/rsif.2009.0013.focus) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Delhey K., Peters A. 2008. Quantifying variability of avian colours: are signalling traits more variable? PLoS ONE 3, e1689. 10.1371/journal.pone.0001689 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001689) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]