Abstract

We analyse generosity, second-party (‘spiteful’) punishment (2PP), and third-party (‘altruistic’) punishment (3PP) in a cross-cultural experimental economics project. We show that smaller societies are less generous in the Dictator Game but no less prone to 2PP in the Ultimatum Game. We might assume people everywhere would be more willing to punish someone who hurt them directly (2PP) than someone who hurt an anonymous third person (3PP). While this is true of small societies, people in large societies are actually more likely to engage in 3PP than 2PP. Strong reciprocity, including generous offers and 3PP, exists mostly in large, complex societies that face numerous challenging collective action problems. We argue that ‘spiteful’ 2PP, motivated by the basic emotion of anger, is more universal than 3PP and sufficient to explain the origins of human cooperation.

Keywords: altruism, cooperation, experimental economics games, punishment, spite

1. Introduction

The origins of human cooperation are the subject of vigorous debate [1–3]. Drawing on experimental economics games some propose that humans exhibit ‘strong reciprocity’ [4–7]. This is defined as, ‘a predisposition to cooperate with others and to punish those who violate the norms of cooperation, at personal cost, even when it is implausible to expect that these costs will be repaid either by others or at a later date’ [8, p. 153]. Strong reciprocity proponents argue that ‘…under conditions plausibly characteristic of the early stages of human evolution, a small fraction of strong reciprocators could invade a population of self-regarding types’ [8, p. 154]. If we found that people cooperate with cooperators, defect on defectors (second party punishment) and punish those who defect on others (third party punishment), we might conclude that strong reciprocity explains the origins of human cooperation. However, we present results here that cast doubt on that explanation of the origins of human cooperation.

In a previous paper, we reported that there is less third party punishment (3PP) in small societies than in large societies [9]. Here we show that small societies are also less generous than large societies. Most importantly, however, we show that small societies do engage in as much second party punishment (2PP) as large societies. We argue that it is second party, ‘spiteful’ punishment that explains human cooperation in small-scale foraging societies while strong reciprocity is more relevant for understanding the cultural evolution of large, complex, agricultural societies.

A common assumption in the cooperation literature is that small, foraging societies are more cooperative than larger societies [4,6,8]. This is somewhat understandable given the ethnographic description of routine food sharing among foragers [10–14]. Reciprocal altruism [15] in the form of in-kind, delayed reciprocity is often assumed to explain this sharing. However, nepotism [16] can explain sharing within the household. Given the uniquely human sexual division of foraging labour, the sharing of foods between spouses could be mate provisioning or trade (e.g. meat for fruit) [17]. Some of the food sharing across households may be explained by scrounging or forced cooperation [18–21]. Still, food sharing and other forms of cooperation may be partly explained by direct or indirect reciprocity [11,12]. Results from economics games played in a wide range of societies show that people in small-scale societies behave less like strong reciprocators than people in large societies.

The data come from a cross-cultural project conducted in a wide range of societies, including hunter–gatherers, horticulturalists, pastoralists, farmers and city dwellers [22] (electronic supplementary material, table S1). Three anonymous, one-shot games were played with real money. In the dictator game (DG), player one (P1) decides how much (from 0 to 100%) to give player two (P2) from a stake the researcher provides and says is to be divided between P1 and P2. P1 keeps the remainder for himself. The DG offer is a simple, straightforward measure of altruism and generosity [23,24].

There is no reason P1 has to give P2 anything, so how should we interpret positive offers? P1 may recognize or feel that his role is similar to that of a person who wants to initiate direct or indirect reciprocity. The DG is a one-shot, anonymous game with no way for P2 to reciprocate. In real life, however, people accustomed to initiating reciprocal exchanges with ‘partners’ should cooperate on the first move without knowing whether there will be subsequent interactions or not. For delayed reciprocity to evolve, someone has to make the first move and cooperate. If people behave as strong reciprocators, we should expect DG offers to be high, something approaching 50 per cent. An even split on the first move would best convey the intent to cooperate in a reciprocal relationship.

2PP is measured with the ultimatum game (UG) [25]. In the UG, P1 again decides how to divide the stake with P2 and if P2 accepts the offer she gets that amount and P1 gets the remainder. However, if P2 rejects the offer both players get nothing. P2's rejection is her way of employing 2PP to punish stingy P1's. Alternatively, it could be a by-product of a partner choice strategy [26].

3PP is measured with the third-party punishment game (3PPG) [27], in which P1 can give whatever amount of the stake to P2. Just as in the DG, P2 can do nothing about it. However, there is a player 3 (P3) who can return 20 per cent of her allotment (half as much as the stake) to the researcher in order to take away three times that amount from P1.

When P2 rejects an offer of 30 per cent in the UG, presumably out of moral outrage [28–30], she thereby punishes P1 (who wanted to keep 70%). Given that she gets zero instead of 30 per cent, it costs her as well as her stingy partner. We can therefore say her rejection is spiteful. Whether natural selection can favour spite has been the subject of debate, clouded by different definitions of spite [31–37] (electronic supplementary material, appendix S1.1). In the context of these anonymous, one-shot games 2PP is spiteful. P2 gains nothing, yet just to punish P1 pays a cost by taking zero rather than accepting a low offer. In real life, however, 2PP probably eventually results in a benefit to punishers because others learn they cannot easily get away with defecting on them [38]. This explains the single quotes around ‘spiteful’ in our title.

The same can be said of ‘altruism’. In the 3PPG, when P3 gives back to the researcher 20 per cent of her allotment to take money away from P1 who slighted P2, she is being altruistic, presumably feeling that P2 suffered an injustice according to the local social norm. In the context of these anonymous, one-shot games 3PP is altruistic, since P3 stands to gain nothing. In real life, however, such punishers may get a reputation as good citizens and might be rewarded for enforcing standards of fairness for the larger group, hence our single quotes around ‘altruism’ in our previous paper [9]. While 2PP and 3PP are not perfectly comparable (electronic supplementary material, appendix S1.2), we might assume that costly, altruistic punishment by a person who has not been wronged directly would be less common than spiteful punishment by an angry person who has been directly wronged. We show here that this is true of small societies but surprisingly it is not true of large societies. We also investigate whether generosity varies with population size. Box 1 shows what we should expect if strong reciprocity explains the origins of human cooperation.

Box 1. Strong reciprocity's three components, predictions and test results.

| components |

predictions |

results in small societies |

| 1. cooperate | high DG offers (approx. 50%) | low DG offers |

| 2. punish | ||

| (a) second-party punishment | high UG MAO | high UG MAO |

| (b) third-party punishment | high 3PPG MAO | low 3PPG MAO |

2. Methods

The UG and 3PPG were played using the strategy method [39] as reported in Barr et al. [40] and Henrich et al. [22] (electronic supplementary material, appendix S1.3). This allowed us to calculate the minimum acceptable offer (MAO), that is, the minimum amount that the offer must be to avoid punishment. The UG MAO is our measure of 2PP. 3PPG MAO is our measure of 3PP. We took MAO values from Henrich et al. [22] (appendices 1.1 and 1.4). Our measure of generosity is the mean DG offer. We took DG, UG and 3PPG offers from Barr et al. [40].

We analysed the variation in DG offers and MAO's in relation to two measures of population size. Local group population refers to the typical group size people live in, whether that be a camp among mobile foragers, a village among horticulturalists, or a city among industrialized societies (electronic supplementary material, appendix S1.4). Ethnic population is the number of people in the ethno-linguistic group. Ethnic populations were obtained from the Ethnologue database of world languages online [41], or when available from the researcher's own reports [9,42]. In all cases, we use the rank order of these two types of population.

3. Results

As previously reported, the 3PPG MAO was correlated with rank orders of both local group and ethnic population [9]. Ethnic population alone accounted for 56 per cent of the variance in the 3PPG MAO. The same was not true of the UG MAO. UG MAO was not significantly correlated with rank of mean local group size (ρ = 0.315, p = 0.319, n = 12) or ethnic population (ρ = 0.209, p = 0.537, n = 11) with Spearman's rank correlations. A linear regression, controlling for continent produced the same results: UG MAO by local group population (β = 0.355, p = 0.353, d.f. = 8); UG by ethnic population (β = 0.348, p = 0.407, d.f. = 7) (electronic supplementary material, appendix S1.5).

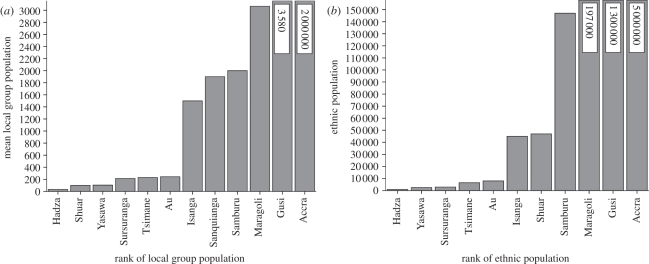

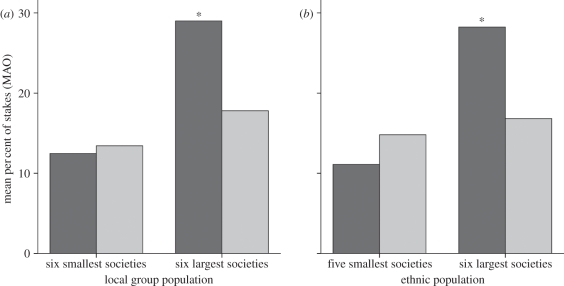

Figure 1a shows local group population and figure 1b ethnic population for each society in order of increasing size. In local group populations there is a clear jump in size between 242 and 1500 and in ethnic populations between 8000 and 45 000. In both cases the break is between the Au and Isanga (electronic supplementary material, appendix S1.6). We used this break to define two groups, the small versus large societies. 3PPG MAO was significantly higher in the large societies than in the small societies. This was true whether we look at the local group population (U = 4, p = 0.026, n1 = 6, n2 = 6) or the ethnic population (U = 3, p = 0.030, n1 = 5, n2 = 6), using Mann-Whitney two-sample, non-parametric tests (figure 2a,b).

Figure 1.

Societies ranked by (a) local group population and (b) ethnic population.

Figure 2.

UG MAO (grey bars) and 3PP MAO (black bars) by smallest versus largest societies as measured by (a) local group population (3PPG MAO: U = 4, p = 0.026); (UG MAO: U = 15, p = 0.699) and (b) ethnic population (3PPG MAO: U = 3, p = 0.030); (UG MAO: U = 15, p = 1). Asterisks indicate p < 0.05.

There was not a significant difference between the small and large societies in the UG MAO. Again, this was true of both local group (U = 15, p = 0.699, n1 = 6, n2 = 6) and ethnic population (U = 15, p = 1, n1 = 5, n2 = 6; figure 2a,b).

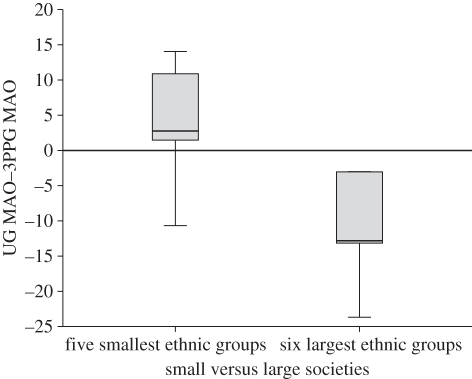

We analysed the relationship between UG and 3PPG MAO's by subtracting the 3PPG MAO from the UG MAO for all societies (electronic supplementary material, appendix S1.7). There was a significant difference in the two amounts of punishment between the small and large societies (U = 2, p = 0.017, n1 = 5, n2 = 6) (figure 3). Large societies engaged in significantly more 3PP than 2PP (local pop: Wilcoxon's Z = −2.201, p = 0.028, n = 6; ethnic pop: Wilcoxon's Z = −2.201, p = 0.028, n = 6). Small societies engaged in more 2PP than 3PP but the difference was not significant (local pop: Wilcoxon's Z = −0.524, p = 0.600, n = 6; ethnic pop: Wilcoxon's Z = −1.214, p = 0.225, n = 5).

Figure 3.

UG MAO minus 3PPG MAO by ethnic population (U = 2, p = 0.017).

Finally, we examined whether larger or smaller societies made more generous offers in the DG. In a linear regression, controlling for continent, DG offers were lower in societies with a smaller local group population (β = 0.746, p = 0.042, d.f. = 8) and with a smaller ethnic population (β = 0.801, p = 0.014, d.f. = 7) (see the electronic supplementary material, figure S1a,b and appendix S1.8). DG, UG and 3PPG offers were all correlated with each other (table 1).

Table 1.

Pearson correlations between DG, UG and 3PPG offers.

| DG | UG | 3PPG | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DG | — | 0.794** | 0.681* |

| UG | 0.794** | — | 0.577* |

| 3PPG | 0.681* | 0.577* | — |

* p < 0.05.

** p < 0.005.

n = 12.

4. Discussion

Societies were either generous in all three games or stingy in all three. Since P1's role in all three games is to decide how much to cooperate with P2 we can say that smaller societies were less cooperative on the first move (electronic supplementary material, appendix S1.9). The small half of our societies (using local group population) tend to be part- or full-time foragers, while the larger half are either pastoralists, farmers, or wage earners. The societies that should most resemble our more distant ancestors are warm-climate hunter–gatherers, and in the ethnographic literature their median ethnic population is 565 [43]. They tend to live in small, mobile groups of about 30 individuals, many of whom are closely related [43–45]. There is little privacy, little property and no such thing as anonymity. They are usually described as egalitarian [44,46]. They are also described as immediate return societies, who strongly discount the future [47]. Evidence from economics games reveals that people who discount the future more heavily are less cooperative than people who do not [48].

Although they were not very generous, people in small societies were no less likely to engage in 2PP than people in larger societies, suggesting they expect to get a fair share even when they do not want to give a fair share. This is more consistent with demand sharing than reciprocity. Such a demand for equity is what explains the egalitarianism of hunter–gatherers. A notable downside to egalitarianism is the inability to solve many collective action problems [49]. Stratification can emerge in response to falling per capita benefits resulting from increasing group size [50]. The levels of political organization familiar to anthropologists (bands, tribes, chiefdoms, states) correspond to increasing population and stratification, along with the cooperation and punishment norms that help manage the increasing number of collective action problems [51].

In contrast to our expectation that ‘altruistic’ 3PP would be less common than the impulsive, ‘spiteful’ reaction of 2PP across all societies, our results tell a different story. Not only did larger societies engage in significantly more 3PP than small societies, 3PP was actually significantly higher than 2PP in large societies. 3PP appears to be the purest expression of social norm enforcement. We suggest that signalling one's generosity and cooperativeness pays off in large societies.

Some foragers have been described as strong norm enforcers who go so far as to carry out third-party executions [52]. It appears, however, that hunter–gatherers do much less of this than all other kinds of societies [46,53–57]. The cases cited nearly always turn out to be people killing someone who is trying to boss them around and are, therefore, 2PP rather than 3PP, even when the killing is carried out by a group [46]. To see why, consider the example of cueing in line. When someone breaks in line in front of you and you reprimand them, this is 2PP even if others in line behind the cheater subsequently join in the punishment (group 2PP). On the other hand if you reprimand someone who breaks in line behind you, this is purely ‘altruistic’ 3PP. Hunter–gatherers have much more individual autonomy than people in larger societies—and when they do enforce norms it is more often 2PP than 3PP.

Those who propose that strong reciprocity (or group selection) explains the origins of human cooperation view the costly rejection of low UG offers (2PP) as altruistic. They suggest that 2PP benefits other group members by discouraging future defections more than it benefits the punisher herself (altruistic spite) [8]. However, hunter–gatherer local groups tend to be ephemeral because group membership is fluid, so any benefits going to group members from someone punishing a defector are short-lived as camp membership changes. The reputation of the ‘spiteful’ punisher, on the other hand, follows her from group to group. We therefore view such 2PP as selfish ‘spite’ that is likely to benefit the punisher who gets a reputation as someone who will not tolerate defection and is therefore less likely to be the target of future defections [58–60]. We think ethnic population is more meaningful than local group population in terms of norms (especially among foragers) because members of a local group frequently change but one belongs to one's ethnic group for life.

The conditions for cooperation are more challenging in larger societies owing to the greater temptation to defect when there is greater status variation and wealth disparity, and when anonymity means defectors may go undetected. It is also more difficult to keep track of interactions with more people [61]. We propose that larger societies which hit upon 3PP institutions had an advantage solving collective action problems (electronic supplementary material, appendix S1.10). The resulting cooperation raised the limits on manageable population size preventing such societies from fissioning, allowing them to expand and exterminate or assimilate other groups.

Unlike humans, chimpanzee show no altruism or spite in these games—only selfishness [62]. When people play the UG against a computer, P2's will accept much lower offers because the computer has no social norms and there is no way to influence it to cooperate through spiteful rejections [63]. The frequent 2PP in all human societies, small and large, illustrates that what is special about humans is the willingness to be spiteful to force cooperation. We include the single quotes around spiteful because we do think it probably results in a reputation that pays in the long-run, possibly as part of a partner-switching strategy of dealing with unfair partners.

In summary, we show that people in very small-scale societies are less generous and are less willing to engage in 3PP than people in large societies. However, they are no less willing to engage in 2PP (see the electronic supplementary material, appendix S1.11). Despite foragers' relative inability to solve some collective action problems, life in small societies is not Hobbesian (see the electronic supplementary material, appendix S1.12). 2PP (in addition to nepotism and mutualism) is enough to ensure cooperation where there are fewer demanding collective action problems. It is mainly ‘spiteful’ 2PP that is relevant for understanding the origins of human cooperation.

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Science Foundation (grant no. 0136761 to Jean Ensminger and Joe Henrich) for supporting the cross-cultural project. We also thank two anonymous reviewers for their very helpful comments.

References

- 1.Gintis H., Henrich J., Bowles S., Boyd R., Fehr E. 2008. Strong reciprocity and the roots of human morality. Social Justice Res. 21, 241–253 10.1007/s11211-008-0067-y (doi:10.1007/s11211-008-0067-y) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hagen E. H., Hammerstein P. 2006. Game theory and human evolution: a critique of some recent interpretations of experimental games. Theor. Popul. Biol. 69, 339–348 10.1016/j.tpb.2005.09.005 (doi:10.1016/j.tpb.2005.09.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Price M. E. 2008. The resurrection of group selection as a theory of human cooperation. Social Justice Res. 21, 228–240 10.1007/s11211-008-0064-1 (doi:10.1007/s11211-008-0064-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyd R., Gintis H., Bowles S., Richerson P. J. 2003. The evolution of altruistic punishment. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 3531–3535 10.1073/pnas.0630443100 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0630443100) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fehr E., Fischbacher U., Gachter S. 2002. Strong reciprocity, human cooperation and the enforcement of social norms. Hum. Nat. 13, 1–25 10.1007/s12110-002-1012-7 (doi:10.1007/s12110-002-1012-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fehr E., Gachter S. 2002. Altruistic punishment in humans. Nature 415, 137–140 10.1038/415137a (doi:10.1038/415137a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gintis H. 2000. Strong reciprocity and human sociality. J. Theor. Biol. 206, 169–179 10.1006/jtbi.2000.2111 (doi:10.1006/jtbi.2000.2111) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gintis H., Bowles S., Boyd R., Fehr E. 2003. Explaining altruistic behavior in humans. Evol. Hum. Behav. 24, 153–172 10.1016/S1090-5138(02)00157-5 (doi:10.1016/S1090-5138(02)00157-5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marlowe F. W., et al. 2008. More altruistic punishment in larger societies. Proc. R. Soc. B 275, 587–590 10.1098/rspb.2007.1517 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1517) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bahuchet S. 1990. Food sharing among the Pygmies of Central Africa. Afr. Study Monogr. 11, 27–53 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gurven M. 2004. To give and to give not: the behavioral ecology of human food transfers. Behav. Brain Sci. 27, 543–583 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaplan H., Hill K. 1985. Food sharing among Ache foragers: tests of explanatory hypotheses. Curr. Anthropol. 26, 223–246 10.1086/203251 (doi:10.1086/203251) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kitanishi K. 1998. Food sharing among the Aka hunter–gatherers in northeastern Congo. Afr. Stud. Monogr. 25, 3–32 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winterhalder B. 1986. Diet choice, risk, and food sharing in a stochastic environment. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 5, 369–392 10.1016/0278-4165(86)90017-6 (doi:10.1016/0278-4165(86)90017-6) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trivers R. L. 1971. The evolution of reciprocal altruism. Q. Rev. Biol. 46, 35–57 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamilton W. D. 1964. The genetical evolution of social behavior. J. Theor. Biol. 7, 1–16 10.1016/0022-5193(64)90038-4 (doi:10.1016/0022-5193(64)90038-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marlowe F. W. 2007. Hunting and gathering: the human sexual division of foraging labor. Cross Cult. Res. 41, 170–195 10.1177/1069397106297529 (doi:10.1177/1069397106297529) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blurton Jones N. G. 1987. Tolerated theft: suggestions about the ecology and evolution of sharing, hoarding, and scrounging. Soc. Sci. Info. 26, 31–54 10.1177/053901887026001002 (doi:10.1177/053901887026001002) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peterson N. 1993. Demand sharing: reciprocity and the pressure for generosity among foragers. Am. Anthropol. 95, 860–874 10.1525/aa.1993.95.4.02a00050 (doi:10.1525/aa.1993.95.4.02a00050) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winterhalder B. 1996. Marginal model of tolerated theft. Ethol. Sociobiol. 17, 37–53 10.1016/0162-3095(95)00126-3 (doi:10.1016/0162-3095(95)00126-3) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woodburn J. 1998. Sharing is not a form of exchange: an analysis of property-sharing in immediate-return hunter–gatherer societies. In Property relations: renewing the anthropological tradition (ed. Hann C. M.), pp. 48–63 Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henrich J., et al. 2006. Costly punishment across human societies. Science 312, 1767–1770 10.1126/science.1127333 (doi:10.1126/science.1127333) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forsythe R., Horowitz J. L., Savin N. E., Sefton M. 1994. Fairness in simple bargaining experiments. Games Econ. Behav. 6, 347–369 10.1006/game.1994.1021 (doi:10.1006/game.1994.1021) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zak P. J., Stanton A. A., Ahmadi S. 2007. Oxytocin increases generosity in humans. PLoS ONE 2, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guth W., Schmittberger R., Schwarze B. 1982. An experimental-analysis of ultimatum bargaining. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 3, 367–388 10.1016/0167-2681(82)90011-7 (doi:10.1016/0167-2681(82)90011-7) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sylwester K., Roberts G. 2010. Cooperators benefit through reputation-based partner choice in economic games. Biol. Lett. 6, 659–662 10.1098/rsbl.2010.0209 (doi:10.1098/rsbl.2010.0209) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fehr E., Fischbacher U. 2004. Third-party punishment and social norms. Evol. Hum. Behav. 25, 63–87 10.1016/S1090-5138(04)00005-4 (doi:10.1016/S1090-5138(04)00005-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abbink K., Bolton G. E., Sadrieh A., Tang F. F. 2001. Adaptive learning versus punishment in ultimatum bargaining. Games Econ. Behav. 37, 1–25 10.1006/game.2000.0837 (doi:10.1006/game.2000.0837) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pillutla M. M., Murnighan J. K. 1996. Unfairness, anger, and spite: emotional rejections of ultimatum offers. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 68, 208–224 10.1006/obhd.1996.0100 (doi:10.1006/obhd.1996.0100) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanfey A. G., Rilling J. K., Aronson J. A., Nystrom L. E., Cohen J. D. 2003. The neural basis of economic decision-making in the ultimatum game. Science 300, 1755–1758 10.1126/science.1082976 (doi:10.1126/science.1082976) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Foster K. R., Wenseleers T., Ratnieks F. L. W. 2001. Spite: Hamilton's unproven theory, pp. 229–238 Helsinki, Finland: Finnish Zoological Botanical Publishing Board [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gardner A., West S. A. 2004. Spite and the scale of competition. J. Evol. Biol. 17, 1195–1203 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2004.00775.x (doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2004.00775.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamilton W. D. 1970. Selfish and spiteful behaviour in an evolutionary model. Nature 228, 1218–1220 10.1038/2281218a0 (doi:10.1038/2281218a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamilton W. D. 1971. Selection of selfish and altruistic behaviour in some extreme models. In Man and beast: comparative social behavior (eds Eisenberg J. F., Dillon W. S.), pp. 51–91 Washington, DC: Smithsonian Press [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lehmann L., Bargum K., Reuter M. 2006. An evolutionary analysis of the relationship between spite and altruism. J. Evol. Biol. 19, 1507–1516 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2006.01128.x (doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2006.01128.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trivers R. L. 1985. Social evolution. Menlo Park, CA: Benjamin Cummings Publishing Co, Inc [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilson E. O. 1975. Sociobiology: the new synthesis. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnstone R. A., Bshary R. 2004. Evolution of spite through indirect reciprocity. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 271, 1917–1922 10.1098/rspb.2003.2581 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2581) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Selten R. 1967. Die Strategiemethode zur Erforschung des eingeschränkt rationalen Verhaltens im Rahmen eines Oligopolexperiments. In Beiträge zur experimentellen Wirtschaftsforschung (ed. Sauermann H.), pp. 136–168 Tübingen: Mohr [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barr A., et al. 2009. Homo aequalis: a cross-society experimental analysis of three bargaining games. Discussion Paper Series, 422. Department of Economics, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

- 41.Grimes B. F. 2000. Ethnologue: languages of the world. Dallas, TX: SIL International [Google Scholar]

- 42.Henrich J., Boyd R., Bowles S., Gintis H., Camerer C., Fehr E. (eds) 2004. Foundations of human sociality: economic experiments and ethnographic evidence from fifteen small-scale societies. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marlowe F. W. 2005. Hunter–gatherers and human evolution. Evol. Anthropol. 14, 54–67 10.1002/evan.20046 (doi:10.1002/evan.20046) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kelly R. L. 1995. The foraging spectrum. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee R. B., DeVore I. 1968. Man the hunter. Chicago, IL: Aldine [Google Scholar]

- 46.Woodburn J. 1982. Egalitarian societies. Man 17, 431–451 10.2307/2801707 (doi:10.2307/2801707) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Woodburn J. 1980. Hunters and gatherers today and reconstruction of the past. In Soviet and western anthropology (ed. Gellner E.), pp. 95–117 London, UK: Duckworth [Google Scholar]

- 48.Curry O. S., Price M. E., Price J. G. 2008. Patience is a virtue: cooperative people have lower discount rates. Pers. Individual Differ. 44, 780–785 10.1016/j.paid.2007.09.023 (doi:10.1016/j.paid.2007.09.023) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marlowe F. W. 2009. Hadza cooperation: second-party punishment yes, third-party punishment no. Hum. Nat. 20, 417–430 10.1007/s12110-009-9072-6 (doi:10.1007/s12110-009-9072-6) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boone J. L. 1992. Competition, conflict, and the development of social hierarchies. In Evolutionary ecology and human behavior (eds Smith E. A., Winterhalder B.), pp. 301–337 New York, NY: Aldine de Gruyter [Google Scholar]

- 51.Johnson A. W., Earle T. 1987. The evolution of human societies. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boehm C. 1993. Egalitarian behavior and reverse dominance hierarchy. Curr. Anthropol. 34, 227–254 10.1086/204166 (doi:10.1086/204166) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Black D. 2000. On the origin of morality. J. Conscious. Stud. 7, 107–119 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Daly M., Wilson M. 1988. Homicide. New York, NY: Aldine de Gruyter [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kelly R. C. 2000. Warless societies and the origin of war. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wiessner P. 2005. Norm enforcement among the Ju/'hoansi bushmen: a case of strong reciprocity? Hum. Nat. 16, 115–145 10.1007/s12110-005-1000-9 (doi:10.1007/s12110-005-1000-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Woodburn J. 1979. Minimal politics: the political organization of the Hadza of north Tanzania. In Politics in leadership (eds Shack W. A., Cohen P. S.), pp. 244–266 Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fehr E., Schneider F. 2010. Eyes are on us, but nobody cares: are eye cues relevant for strong reciprocity? Proc. R. Soc. B 277, 1315–1323 10.1098/rspb.2009.1900 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.1900) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Barclay P. 2006. Reputational benefits for altruistic punishment. Evol. Hum. Behav. 27, 325–344 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2006.01.003 (doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2006.01.003) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rockenbach B., Milinski M. 2006. The efficient interaction of indirect reciprocity and costly punishment. Nature 444, 718–723 10.1038/nature05229 (doi:10.1038/nature05229) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boyd R., Richerson P. J. 1988. The evolution of reciprocity in sizeable groups. J. Theor. Biol. 132, 337–356 10.1016/S0022-5193(88)80219-4 (doi:10.1016/S0022-5193(88)80219-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jensen K., Hare B., Call J., Tomasello M. 2006. What's in it for me? Self-regard precludes altruism and spite in chimpanzees. Proc. R. Soc. B 273, 1013–1021 10.1098/rspb.2005.3417 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3417) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Blount S. 1995. When social outcomes aren't fair: the effect of causal attributions on preferences. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 63, 131–144 10.1006/obhd.1995.1068 (doi:10.1006/obhd.1995.1068) [DOI] [Google Scholar]