Abstract

Background

Risk taking is a significant health-compromising behavior among children that often is portrayed unrealistically in the media as consequence-free. Physical risk taking can lead to injury, and injury is a leading cause of hospitalization and death during childhood.

Objective

To examine the effectiveness of a 4-week program for school-age children in reducing risk-taking behaviors and increasing safety behaviors.

Method

A 2-group, experimental, repeated-measures design was used to compare 122 White and Latino children randomly assigned to an intervention group or a wait-list group at baseline, and at 1, 3, and 6 months after intervention. Children received a behaviorally based intervention delivered in four 2-hour segments conducted over consecutive weeks. The thematic concept of each week (choices, media, personal risk taking, and peer group risk taking) moved from the general to the specific, focusing on knowledge and awareness, the acquisition of new skills and behaviors, and the supportive practice and application of skills.

Results

Participants increased their safety behaviors (p = .006), but risk-taking behaviors remained unchanged. Families in the intervention group increased their consistent use of media rules (p = .022), but decreases in media alternatives suggest difficulty in taking up other habits and activities. Coping effectiveness was predictive of safety behaviors (p = .005) at 6 months and coping effectiveness plus television watching was predictive of risk taking (p = .03).

Conclusions

Findings from this study suggest that interventions that influence children’s media experiences help enhance safety behaviors and that strategies to aid parents in finding media alternatives are relevant to explore.

Keywords: children, risk taking, safety behaviors, television

Risk taking is a significant behavior that compromises health, and an expansive literature has emerged that describes the rapidly deteriorating and interrelated nature of health risk behaviors in American youth. Physical risk taking can lead to injury, and injury is a leading cause of hospitalization during childhood. Speltz, Gonzales, Sulzbacher, and Quan (1990) found that children with two injuries or more scored significantly higher on risk taking (mean, 33.7) utilizing a primary care based tool the Injury Behavior Checklist (IBC) than children with no injuries (mean, 22) and 1 injury (mean, 24). Kennedy replicated those results finding that the IBC was predictive of the injury outcome in both White (Kennedy & Lipsitt, 1998) and Latino children (Kennedy & Rodriguez, 1999). Unintentional injury is the leading cause of death for children more than 1 year of age; more children die from injuries than from all diseases combined.

Injury is a phenomenon that is underrepresented in nursing research, which is surprising given the focus on health promotion in the field (Sommers, 2006). This lack of research on injury is especially critical given that rates for counseling about injury prevention remain low and have not changed in the past 2 decades in primary care except in two specific areas (poison control and bike helmet use). ). Yet, research based on the national Injury Control and Risk Survey and earlier studies has shown that counseling by health care providers about injury prevention promotes safer behaviors (Chen, Kresnow, Simon, & Dellinger, 2007).

Health science researchers have established that children’s media consumption affects their health behaviors and is one of the factors that influence risk taking in children. Risk taking is portrayed in the media as consequence-free, and outcomes rarely are depicted realistically. Harmful outcomes are depicted in only 3% of prime-time television shows. If these shows were realistic, viewers would see 15 injuries per hour in adult shows, 24 injuries per hour during Saturday morning shows, and 46 injuries per hour in afternoon children’s shows. Potts, Doppler, and Hernandez (1994) experimentally manipulated children’s exposure to TV cartoons that depicted high- or low-risk behaviors and demonstrated that the children who saw the high-risk content reported a greater willingness to take risks. In 1998, Potts and Swisher demonstrated that exposure to safety education videos decreased a child’s willingness to take physical risks. Children are aware of their risk-taking behavior, and their intentions to take risk closely align with how they behave in risk situations (Morrongiello, 2004; Potts, Martinez, & Dedmon, 1995).

Kennedy (2000a) found that preschool-age children who often take physical risks watch more television and have parents with little media knowledge and few family media rules who provide little media monitoring. Gender, acculturation, and ethnicity influenced both the types of shows viewed and the amount of viewing time among White and Latino children and the rates of risk taking and injuries (Kennedy, 2000a, 2000b). Young school-age children report television as a friend and look upon it not only as entertainment but more importantly as a source of information, educating them on how to act in the world of grown-ups—a world that developmentally they are anxious to join and fit into (Kennedy, Strzempko, Danford, & Kools, 2002). Some work suggests that television viewing is chosen by children as a coping strategy, albeit a strategy that they view as not very effective (Chen & Kennedy, 2005). Children also report that at least 50% of their viewing time is by default, in that they watch television in order to spend time with their parents who are themselves watching television (Kennedy, 2000b; Kennedy et al., 2002). Despite parents’ avowed beliefs that they regulate their child’s exposure to negative media influences and encourage only positive shows, a serious gap exists between this belief and the actual viewing of television by children (Kennedy, 2000a).

Few researchers have documented how other healthier choices can be developed in school-age children. In general, the body of research tends to be focused on teenagers and the remediation of poor choices once such choices have been established. Recent work focused on identifying assets within the teen years suggests that identifying the antecedents to these positive behaviors would be appropriate for health interventionists. Children’s health beliefs, perceptions, and practices such as risk-taking behaviors are stable by 9 to 11 years of age; therefore, efforts to influence these behaviors should be made with younger school-age children. Most interventions to reduce television viewing are prescriptive, and even successful approaches to reducing daily television viewing time leave one to wonder whether the behavior can be maintained. It seems justifiable to enhance children’s understanding of the skewed media portrayal and to do so via a self-choice and self-care model.

Risk taking by children is influenced by a variety of persons (child, parent, teachers), environmental factors (neighborhood, culture), and social factors (peers, media). Given the adverse health consequences of media consumption by children and the developmental trajectory of negative health behaviors, the socialization of children’s health behaviors remains surprisingly underexplored by nursing.

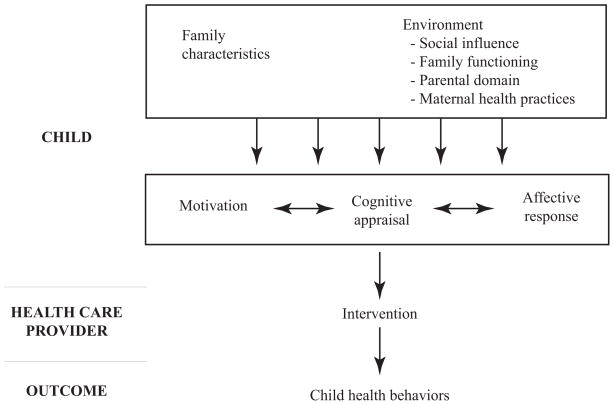

One model that includes socialization of health behaviors is Cox’s Interaction Model of Client Health Behavior (IMCHB). This conceptual model is grounded in a multidisciplinary perspective on the dynamic interplay between clients, the health professional’s interaction with the child and family, and health outcomes (Figure 1; Carter & Kulbok, 1995; Farrand & Cox, 1993). The model suggests that changes in children’s health behaviors by health care interventions occur via a change in the child’s cognitive appraisal (i.e., their health perception) and that intrinsic motivation and affective response (i.e., perceived self-competency) exert their influence on the child’s cognitive appraisal. Farrand and Cox (1993) reported a fairly strong confirmation of the models proposed linkages identifying gender-specific determinants of children’s health behaviors. They reported that the central role of cognitive appraisal/health perception is to mediate the effects of affective responses (perceived competency) and motivation on the outcome of health behaviors. Although the published model does not address coping specifically, our earlier work supported investigating it because children reported television watching as one of their most frequent, but ineffective coping strategies (Chen & Kennedy, 2005).

Figure 1.

Child health behaviors and intervention model

The primary aim of this prospective, randomized, 4-year longitudinal study was to test a peer group intervention aimed at decreasing physical risk-taking behaviors by influencing children’s media behaviors, understanding, and choices. Guided by the IMCHB model, factors that were examined included the child’s motivation, health perceptions, and self-competencies. Children’s coping strategies; parents’ safety, media practices, and beliefs; and family functioning also were explored.

Methods

A two-group, experimental, longitudinal design was used to compare children who were randomly assigned to the intervention group (n = 57) or to a wait-list control group (n = 65) at four times: baseline (T1) and 1 month (T2), 3 months (T3), and 6 months (T4) after the intervention.

Participants

Sixteen sites provided a total of 34 groups with an average of four children in a group. Of the 145 parents and children who were approached to participate, 11 declined because of time or activity conflicts and another 12 did not meet eligibility requirements. A total of 122 children (ages 8 and 9 years) and their mothers participated in the study (58 White and 64 Latino); the randomly assigned sample included 58 girls (47.5%) and 64 boys (52.5%). The groups were balanced in distribution by gender and ethnicity. No attrition or loss of participants was noted during the study. All children and parents completed the baseline assessment and the three follow-up assessments.

Procedures

Human subject protection was approved by the University of California, San Francisco Committee on Human Research. Upon approval, subjects were solicited from community sources and after school programs in Northern California. Eight-year-old children and their parents were eligible for enrollment if they met the following criteria: (a) the adult and child self-identified their ethnicity as either Latino or White; (b) the child was in good health, defined as free of an acute or life-threatening disease and able to attend to activities of daily living such as going to school; (c) parents, in addition to speaking either English, Spanish, or both, were able to read in one of the two languages in order to fill out questionnaires written at a fourth- to sixth-grade level; and (d) parent and child participants resided in the same household.

After written consent was obtained from a parent, White and Latino families were assigned randomly to an intervention group or a control (wait-list) group using a random numbers table. Intervention groups received a 4-week program and completed measures at baseline (before the intervention) and 1, 3, and 6 months after the intervention. The wait-list control groups completed the same measures at the same time intervals. After the 6-month data collection, the control group also received the intervention. All children’s data were self-reported and obtained at each child care site by using an interactive game on a laptop with software designed for the study (Kennedy, Charlesworth, & Chen, 2003). Each child logged on with a password-protected ID number, their data was encrypted, and the data was uploaded and transferred to SPSS files. Parents used traditional pen and paper questionnaires in their preferred language and returned the completed forms by mail.

Verbal assent was obtained from all children, and confidentiality, group rules, and general guidelines were discussed with the children. Children received incentives (books and small surprises) each week of the program and a $20 gift certificate to a toy store upon completion of the program. Parents were given a $20 gift certificate to a local food market.

Intervention

The intervention program was designed for small groups of four to six children, facilitated by a research team nurse or health counselor. Four interventionists were trained by the primary investigator and project director in a group workshop model and utilized a standardized procedural manual for each of the sessions. The project director routinely monitored the delivery of sessions through random direct observation visits and all interventionists participated in training refresher sessions every 6 months. Details of the behavioral basis of the program, process evaluation, and treatment fidelity are reported elsewhere (Kennedy & Floriani, 2008).

The program comprised four content segments, conducted during consecutive weekly sessions. The thematic concept of each week moved from the general to the specific, focused on knowledge and awareness, the acquisition of new skills and behaviors, and the supportive practice and application of the skills. Essential to learning and internalizing the information presented, each week of the program allowed for repetition and practice within the group and at home. Although parents did not participate directly in the program, they did receive weekly information packets containing media and health concepts similar to the content the children received that week. The concept of each program segment was reviewed further during the following week, in relation to the activities children had practiced at home and as an introduction for the related successive concept.

Measures

Five age-appropriate instruments designed for children and five instruments for parents that had literacy levels established at lower-grade-school readability were used (Table 1).

Table 1.

Instruments Used to Assess Children and Their Families

| Instrument | Assessment | Subscales | Score range | Psychometric properties |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Perception Profile | Affect in children 8 to 12 years old | Scholastic competence Athletic competence Social acceptance Physical appearance Behavioral conduct Global self-worth |

Likert scale, 1 (low) to 4 (high) | Internal consistency reliability α, .80 to .85 for scholastic competence, .80 to .86 for athletic competence, .75 to .80 for social acceptance, .76 to .82 for physical appearance, .71 to .77 for behavioral conduct, and .78 to .84 for global self-worth |

| How Often Do You? | Child’s health behaviors | Safety Junk food Activity Nutrition Hygiene Assertiveness |

1 (low frequency) to 4 (high frequency) | Cronbach’s α, .86–.91 |

| Child’s Health Self-Concept Scale | Children’s perception of their health | Psychosocial issues Physical health Values Energy and healthiness |

Summative rating scale from 1 (negative health self-concept) to 4 (positive health self-concept) | Moderate stability High internal consistency reliability (.82) Evidence of content validity |

| Schoolager’s Coping Strategies Inventory | Coping in children ages 8 to 12 years | Frequency of use of coping strategy Effectiveness of coping strategy |

0 (low) to 3 (high) | Construct validity Internal consistency (r = .79) Test-retest reliability (r = .73–.82) Cronbach’s α reliability coefficients: .84 for frequency subscale, .85 for effectiveness subscale |

| Short Acculturation Scale | Acculturation of Latino families | Validity criteria: Respondents’ generation Length of residence in the United States Age on arrival in the United States |

Average of scores on Likert scale from 1 to 5; scores ≤2.99 low, scores >2.99 high | Correlated with respondents’ generation (r = .69), length of residence in the United States (r = .76), and age on arrival in the United States (r = .72) |

| Family Assessment Device | Family functioning | Problem solving Communication Roles Affective responsiveness Affective involvement Behavior control General functioning |

Likert scale, 1 (strongly agree) – 4 (strongly disagree) Higher scores indicate poorer function |

Cronbach’s α: .73 for problem solving, .72 for communication, .70 for roles, .69 for affective responsiveness, .64 for affective involvement, .52 for behavior control, and .82 for general functioning. |

| Media Quotient | Family media habits and beliefs | Media use Monitoring Consistency Media effects Media knowledge Alternative activities |

Likert scale always(1) - never (5) | Reliability coefficients: Media use, α = .75; Monitoring, α = .89; Consistency, α = .73; Media effects, α =.63; Media knowledge, α = .25; and Alternative activities, α = .66 Test-retest correlations: Media use, r = .96; Monitoring, r = .82; Consistency, r = .89; Media effects, r = .84; Media knowledge, r = .81; Alternative activities, r = .82 |

| Health Self- Determinism Index–Children | Motivation of children | Self-determinism in health behavior, Competency in health matters, Internal-external cue responsiveness, Self-determinism in health judgment | 1 (maximum extrinsic orientation) to 4 (maximum intrinsic orientation) | Internal consistency (Cronbach’s α), .78 2-week test-retest correlation for total tool, .83. |

| Injury Behavior Checklist | Parents report on frequency of children’s risk- taking behaviors in past 6 months | 24 items describing risk- taking behaviors | 0 (not at all) 1 (very seldom, has happened once to twice) 2 (sometimes, about once a month) 3 (pretty often, about once a week) 4 (very often, more than once a week) Total sum for all 24 items, 0 to 96 |

Internal consistency, .84–.92 1-month test-retest correlation, .81 Specificity adequate |

| Framingham Safety Survey | Parents describe home-based safety practices | 19 questions on injury prevention and safety behaviors | 1 (low) to 3 (high) safety for each response, with a total score from 19 to 57. Higher scores reflect greater safety behaviors | Internal reliability (Cronbach’s α), .86 External reliability, p = .40 Validity, r = .69 in English, 1.0 in Spanish |

Affective

The Self-Perception Profile (SPP) is a 36-item questionnaire for assessing self-perceptions of competencies in children in third grade and older (Table 1).

Child’s health behaviors

The reported overall health behaviors of the child were measured with a 36-item Likert scale called How Often Do You? (HODY). Stember, Swanson-Kaufman, Goodwin, Rogers, and Mathews (1984) reported that content and concurrent validity were demonstrated sufficiently by this instrument (Table 1).

Cognitive

The Child’s Health Self-Concept Scale (CHSCS) is used to measure children’s cognitive appraisal (perception) of health (Hester, 1984). This 45-item scale takes approximately 15 minutes for the child to complete. Based on a diverse sample of 940 children, the authors originally created four subscales (Table 1), but because further analysis suggested that a single attribute is being measured, only a total score is reported.

Coping

The Schoolager’s Coping Strategies Inventory (SCSI) is a 26-item self-report instrument used to measure the type, frequency, and effectiveness of coping strategies used by children (Ryan-Wenger, 1990). Each child identifies a stressor and then scores each coping strategy for frequency of use and for degree of helpfulness (Table 1).

Family characteristics

Demographics were collected with a 31-item parent questionnaire for educational, financial, and social descriptive data. A 12-item Short Acculturation Scale (Marin, Sabogal, Marin, Oter-Sabogal, & Perez-Stable, 1987) was used to measure the acculturation level of Latino families. The Acculturation Scale has demonstrated good psychometric properties in both its English and Spanish version (Table 1).

Family functioning

The Family Assessment Device (FAD) has six specific subscales (Epstein, Baldwin, & Bishop, 1983) and a 12-item general functioning subscale that has been used as a global assessment of general health of the family (Table 1). Several studies have reported concurrent validity of the FAD as ranging from 0.48 to 0.53 and reliabilities from 0.69 to 0.86 (Kabakoff, Miller, Bishop, Epstein, & Keitner, 1990; Miller, Ryan, Keitner, Bishop, & Epstein, 2000).

Family media

The Media Quotient was used to measure family media habits and beliefs about the effects of media (Gentile & Walsh, 2002). The reliability coefficients and test-retest correlations for the six indices of the Media Quotient are listed in Table 1. Gentile and Walsh reported that the low reliability coefficient for the Media Knowledge index was expected because of the wide range of topics measured by this index (it was a heterogeneous index, whereas other indices were homogeneous). Across all items, the mean test-retest correlation is .75. The mean test-retest correlation for the six indices is .85. Validity was supported by the negative correlations between children’s television viewing and each of the indices.

Motivation

The Health Self-Determinism Index–Children (HSDI–C) is composed of 32 forced-choice Likert format items divided over 4 subscales (Cox, 1985). Children were asked to decide which kind of kid is most like themselves and then are asked whether this is only sort of true or really true for them (Table 1).

Risk taking

The Injury Behavior Checklist (IBC) is a reporting measure for parents that contains 24 items describing various specific risk-taking behaviors and minor injurious mishaps for children up to age 9 years (Table 1). The IBC score is predictive of subsequent injuries; reported mean scores range from 18–33 in diverse populations (Bass & Mehta, 1980; Bernardo, 1996; Kennedy & Rodriguez, 1999; Potts et al., 1995; Potts et al., 1997).

Safety behaviors

The American Academy of Pediatrics Framingham Safety Survey (FSS) for ages 5 to 9 years is a 19-question parent report on home-based safety practices used to gather information so that caregivers in primary care clinical settings can provide counseling about injury prevention and safety behaviors (Table 1). The FSS also is referred to as The Injury Prevention Program Safety Survey. Five developmentally age-specific versions of the FSS are available in both English and Spanish. Psychometric properties (Table 1) reported for the younger FSS support acceptable internal and external reliability and validity for parent report (Mason, Christoffel, & Sinacore, 2007).

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were examined initially for demographic characteristics and all major study variables. The intervention and control groups were compared by using t tests to check for any major dissimilarity between the study groups at baseline. Partial correlation coefficients, controlling for gender, weight status, ethnicity, and group membership (intervention versus control), were computed to examine variables related to risk-taking and safety behaviors. Stepwise regressions were used to examine factors from the baseline data that contributed to children’s safety and risk-taking behaviors. Examined was whether the rate of change in children in the intervention group was different than the rate among children in the control group by fitting linear mixed-effects models that include functions of time and group effects to the repeated child data. Analyses were performed with SPSS 15.0, and mixed modeling was performed by using SAS version 8.

Results

Approximately 86% of White and 22% of Latina mothers had completed a high school education. Four percent of White families and 38% of Latino families had annual incomes less than $20,000, whereas 82% of White families and 8% of Latino families had annual incomes greater than $40,000. Significantly more Latino mothers (77%) than White mothers (66%) were married (χ2 = 13.05, p = .023). Most of the Latino mothers (93%) were highly acculturated; 40% were United States natives. The 60% who were born elsewhere had resided in the United States for more than 10 years.

Total scores on risk taking were significantly higher in boys (14.6) than in girls (11.0; t = 2.23, p < .02) and in normal weight (15.0) than in overweight children (10.0; t = 2.59, p < .01). Mean scores for the major child model variables did not differ significantly between the children in the two groups at baseline (Table 2).

Table 2.

Child Variables (Means and Standard Deviation)

| Variable | Intervention | Control | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | |

| Framingham Safety Survey | ||||||||

| 41.41 (0.68) | 43.95 (0.74) | 44.70 (0.70) | 45.09 (0.66) | 43.48 (0.68) | 44.19 (0.89) | 43.87 (0.76) | 44.09 (0.79) | |

| Injury Behavior Checklist | ||||||||

| 13.62 (1.10) | 14.20 (1.29) | 11.91 (1.19) | 11.31 (1.14) | 12.50 (1.11) | 12.13 (1.51) | 12.93 (1.30) | 11.58 (1.35) | |

| Health Self-Determinism Index–Children | ||||||||

| Behavior | 35.94 (6.31) | 37.33 (7.10) | 37.27 (6.16) | 37.09 (6.87) | 36.51 (6.05) | 37.12 (6.68) | 36.85 (5.63) | 36.16 (8.96) |

| Internal: External Cue | 14.15 (4.27) | 14.06 (4.20) | 13.27 (3.75) | 13.54 (6.87) | 13.37 (3.97) | 14.38 (4.00) | 14.33 (4.28) | 14.00 (4.27) |

| Competence | 15.70 (4.07) | 14.90 (5.01) | 14.75 (4.04) | 13.92 (4.20) | 15.37 (3.97) | 14.20 (3.90) | 14.21 (4.06) | 14.91 (4.41) |

| Judgment | 7.31 (2.43) | 7.21 (2.84) | 6.72 (2.66) | 6.06 (2.37) | 6.92 (2.67) | 6.65 (2.80) | 6.47 (2.76) | 7.03 (2.9) |

| Self-Perception Profile | ||||||||

| Scholastic Competence | 17.75 (4.22) | 18.63 (3.59) | 18.61 (4.09) | 18.45 (4.08) | 17.61 (3.64) | 18.12 (3.64) | 18.31 (3.42) | 17.46 (4.48) |

| Social Acceptance | 16.48 (4.03) | 16.61 (4.57) | 17.43 (4.63) | 16.90 (4.89) | 16.50 (3.10) | 16.79 (3.59) | 16.97 (3.53) | 17.16 (3.97) |

| Athletic Competence | 17.06 (3.81) | 16.73 (4.16) | 17.31 (3.71) | 17.43 (4.28) | 16.71 (3.51) | 16.38 (3.97) | 16.21 (4.33) | 16.27 (4.00) |

| Physical Appearance | 18.91 (3.87) | 19.12 (4.24) | 19.00 (3.85) | 19.19 (4.27) | 17.98 (4.33) | 18.23 (3.89) | 18.41 (3.77) | 18.03 (4.4) |

| Behavioral Conduct | 18.25 (2.95) | 19.47 (3.26) | 19.27 (3.28) | 18.34 (3.92) | 18.25 (3.46) | 18.84 (3.16) | 19.04 (3.18) | 18.84 (3.88) |

| Global Self-Worth | 19.52 (4.11) | 19.08 (3.73) | 19.29 (3.60) | 19.55 (3.85) | 18.99 (3.00) | 19.32 (3.77) | 19.75 (3.71) | 18.97 (3.75) |

| Child’s Health Self-Concept Scale | ||||||||

| 133.12 (15.02) | 134.34 (17.48) | 136.67 (17.55) | 136.21 (17.15) | 133.45 (14.86) | 136.52 (14.44) | 135.45 (15.28) | 133.68 (14.66) | |

| How Often Do You? | ||||||||

| 114.81 (10.04) | 113.35 (11.94) | 115.92 (10.72) | 116.10 (10.29) | 111.87 (11.43) | 114.00 (11.29) | 113.19 (10.86) | 114.94 (11.58) | |

| Schoolager’s Coping Strategies Inventory | ||||||||

| Frequency | 38.30 (10.39) | 37.84 (10.59) | 38.81 (8.30) | 37.45 (10.30) | 37.21 (10.74) | 36.91 (8.61) | 35.68 (8.80) | 38.31 (9.41) |

| Effectiveness | 44.68 (10.46) | 42.97 (10.06) | 45.46 (9.24) | 42.10 (9.90) | 45.42 (11.71) | 42.64 (8.53) | 42.99 (8.75) | 44.39 (9.52) |

Notes. T1 is baseline, T2 is 1 month after baseline, T3 is 3 months after baseline, and T4 is 6 months after baseline.

Partial correlation coefficients were used to examine correlations between family variables and children’s behaviors, and regression models were computed to explore factors contributing to children’s risk-taking and safety behaviors at baseline. When gender, ethnicity, weight, and group membership were controlled for, it was found that increased television viewing time was related to less use of safety behaviors (r = −.34, p = .009), and to less use of positive media (r = −.32, p = .012). Higher risk taking in children was related significantly to parents’ belief that media do not affect children (r = −.27, p = .036). Higher amounts of television watching also correlated with the child having a negative health self-concept (r = − .54, p < .001).

Stepwise regression models were computed to examine factors contributing to children’s safety and risk-taking behaviors. The children’s age and ethnicity were first, followed by seven subscales of the FAD (problem solving, communication, roles, affective involvement, affective responsiveness, behavior control, and general functioning), six indices from the Media Quotient (alternatives, consistency, effects, knowledge, monitoring, and media use), and total hours of television viewing. At baseline, five variables contributed to lower safety behaviors (adjusted R2 = .37, F = 9.93, p < .0001): poorer problem solving in the family (sr2 = .25); unhealthy (high) affective involvement in the family (sr2 = .08); high use of alternative media in families (sr2 = .08); high television viewing times among children (sr2 = .06); and high use of positive media in the family (sr2 = .07). Four variables were significant in predicting children’s risk-taking behaviors (adjusted R2 = .21, F = 6.70, p < .0001): being White (sr2 = .16), being a boy (sr2 = .03), poor affective responsiveness in the family (sr2 = .10), and better media consistency (consistent use of media rules) in the family (sr2 = .08; Table 3).

Table 3.

Stepwise Multiple Regression Summary Table

| Source | Adjusted R2 | beta | sr2 | df | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Safety Behaviors | ||||||

| Overall | .37 | 5, 70 | 9.93 | .0001 | ||

| Poorer problem solving | −.457 | .25 | 5, 70 | 23.37 | .0001 | |

| High affective involvement | .230 | .08 | 5, 70 | 5.90 | .018 | |

| Better media use | −.250 | .07 | 5, 70 | 4.96 | .029 | |

| High use of alternative media | −.283 | .08 | 5, 70 | 6.22 | .015 | |

| High television viewing time | −.199 | .06 | 5,70 | 4.31 | .041 | |

| High Risk taking | ||||||

| Overall | .21 | 4, 83 | 6.70 | .0001 | ||

| White | −.470 | .16 | 4, 83 | 15.24 | .0001 | |

| Boy | −.170 | .03 | 4, 83 | 2.97 | .05 | |

| Poorer affective response | .378 | .10 | 4, 83 | 9.70 | .003 | |

| Better media consistency | .265 | .08 | 4, 83 | 7.21 | .009 | |

No significant differences were found between groups in children’s affect (SPP), cognition and health perceptions (CHSC), coping strategies, motivation (HSDI-C), or general health behaviors (HODY) during the 6-month period (Table 2). Children evidenced significant decreases in self-determined health judgment (HSDI-C subscale) over time (F = 3.09, p = .03), but no interaction was found between groups and time (F = 1.9, p = .13). Children, on average, watched 18 hours of television weekly. Television watching in the intervention group had decreased to 17 hours weekly by 6 months after the intervention, although this difference was not statistically significant (t = −1.90, p = .07). In the hierarchical mixed model, the intervention group significantly increased their safety behaviors (F = 4.37, p = .006). No difference was found in risk taking over time or between groups (F = .23, p = .87; Table 4). At the 6-month follow-up, families in the intervention group reported two additional changes: an increase in the consistent use of media rules (t = −.241, p = .022) but a decrease in use of alternative activities (t = 2.21, p =.032). To explore these results further, a regression analysis was run on children’s baseline variables as predictors of safety and risk-taking behaviors at 6 months after the intervention. More effective coping by the child at baseline was predictive of higher use of safety behaviors 6 months later (adjusted R2 = .13, F = 8.69, p =.005). Higher television watching time and less effective coping at baseline were predictive of higher risk-taking behaviors at 6 months after the intervention (adjusted R2 = .21, F = 4.78, p = .034).

Table 4.

General Mixed Model Summary Table

| Variables | −2 log likelihood | Group F (p) | Time F (p) | Group × time F (p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Framingham Safety Survey | 1327.3 | .01 (.908) | 9.17 (.001) | 4.37 (.0062) |

| Injury Behavior Checklist | 1948.6 | .017 (.6827) | .50 (.6684) | .23 (.8742) |

| HSDI-C Behavior | 516.6 | .11 (.7421) | .38 (.7697) | .23 (.8744) |

| HSDI-C Competence | 596.6 | .000 (.9884) | 1.22 (.3078) | .70 (.5532) |

| HSDI-C Internal/external | 658.7 | .33 (.5644) | 1.50 (.2201) | 1.60 (.1926) |

| HSDI-C Judgment | 661.2 | .08 (.7839) | 3.09 (.0314) | 1.90 (.1340) |

| SPP Athletic competence | 576.1 | .96 (.3304) | 1.03 (.3836) | .66 (.5783) |

| SPP Behavioral conduct | 553.3 | .09 (.7664) | 1.40 (.2442) | .72 (.5414) |

| SPP Physical appearance | 590.9 | 1.93 (.1673) | .39 (.7625) | .47 (.7071) |

| SPP Scholastic competence | 581.4 | .77 (.3812) | .96 (.4162) | .66 (.5809) |

| SPP Social acceptance | 568.9 | .01 (.9258) | .25 (.8617) | .16 (.9219) |

| SPP Global self-worth | 563.3 | .34 (.5588) | .57 (.6340) | .56 (.6441) |

| Child’s Health Self-Concept | 90.3 | .03 (.8533) | .64 (.5936) | .66 (.5776) |

| How Often Do You? | 2527.9 | .33 (.5671) | 1.53 (.2108) | 1.37 (.2537) |

Notes. HSDI-C = Health Self-Determinism Index–Children; SPP = Self-Perception Profile

Discussion

Theoretical Model

These findings raise issues about the need for further refinement and testing of the IMCHD model in pediatric nursing research. As suggested by Carter and Kulbok, it is possible that cognitive appraisal: (a) should not be captured only as “perceived health status,” (b) needs further development as a construct, and (c) may not be sensitive to developmental change over time. Morrongiello and Mark (2008) reported that by targeting specific risk-taking cognitions, in contrast to general perceived health cognitions, they could reduce children’s risk-taking intentions by using an induced-hypocrisy intervention. Regarding the second point, in construct validity testing, the CHSCS did not discriminate into its original 5 subscales, suggesting little support for the construct validity of the subscales and leaving unknown the construct validity of it as a measure of a single attribute. Our study is the first to use a longitudinal design and repeated measures in children, thus from a developmental perspective, we believe that the third point also has merit.

In both groups, self- determined health judgment decreased significantly in the 6 months after the intervention reflecting movement from an intrinsic to extrinsic orientation. This result is in contrast to the results originally reported by Cox, Cowell, Marion, and Miller (1990), who found a linear trend from extrinsic to intrinsic motivation with increasing age. Those values, however, were based on cohort studies and not on longitudinal changes with the same study population, and they reflect a much wider age range (third-seventh grade). Cox et al. (1990) noted that the 1 year test-retest alpha values decreased and suggested that the measure might be capturing state versus trait behavior. Further psychometric property testing should address whether the HDSI-C is stable for midrange periods such as 6 months if it is to be used fruitfully in future short-term longitudinal studies.

A child’s coping effectiveness was predictive of both safety and risk-taking behaviors 6 months later. This finding suggests that coping strategies should continue to be investigated as a relevant facet of children’s health intervention work, especially given reports that training in coping skills enhances behavioral interventions in diverse areas such as pediatric diabetes (Grey, Boland, Davidon, Li, & Tamborlane, 2000) and weight reduction (Berry, Savoye, Melkus, & Grey, 2007).

Media

At 18 hours a week, the total television watching time of the children in this sample is less than the national average of 21 hours a week but is still not at the American Academy of Pediatrics’ recommendation of 2 hours or less a day (14 hours weekly). Higher risk taking in children was significantly related to parents’ belief that media do not affect children, and yet large amounts of television watching did correlate significantly with children reporting a more negative perception self-concept of their own health. Greater television viewing time was also related to less use of safety behaviors in households.

At the 6-month follow-up, families in the intervention group reported a significant increase in the consistent use of media rules but a decrease in use of alternative activities. These findings suggest that families still need help in creating and maintaining lifestyles that enhance activity choices other than watching television. Future studies attempting to address media use in the parent-child dyad or (even more challenging) the family as a whole will be critical.

Risk Taking and Safety

As expected, boys scored higher than girls scored on risk taking. This finding is in concert with the robust gender differences reported in the injury literature. As in most other studies, we have operationalized risk taking as a physical activity, which might also account for the significantly lower rates of risk taking in overweight children compared with children of normal weight in the study. Green (1997) found that physical risk taking is an important factor in the creation of boys’ social identity. Results of a recent ethnographic study suggest that girls are risk takers when social domains are included and that children’s risk engagement and risk taking are a balancing act between risk willingness and self-care within the context of social relationships, emotional excitement, and connections and activities with other children (Christensen & Mikkelsen, 2008). Possibly the intervention was not motivating enough to lower risk-taking behavior because it did not attend to the social identity and perceptions of other peers in the group. A second potential explanation is that the lack of change might reflect a “floor effect,” where reduction of risk taking is less likely in a group that is already low in risk taking. A third, arises from a recent report by Morrongiello and Matheis (2007), who used IBC scores reported by the child rather than the parent. They found that school-age children routinely engage in greater risk taking than their parents would have them do and that parents often were not told about minor injuries or risk-taking behaviors. This suggests potential underreporting of risk taking by parents of school-age children.

Intervention families showed a significant increase in safety behaviors, and this effect was sustained for the 6 months. The intervention activities of the children that were practiced at home and possibly the parental materials that were sent home influenced modifications in the home environment, as measured by the safety behaviors. Given the baseline predictors of safety behaviors, we suggest that the intervention engaged mothers’ affective-based perspectives and enhanced maternal problem solving. Decisions by mothers to engage in safety practices are driven by affect rather than knowledge, that is, by changes in perception of their specific child’s characteristics that they believe make their child vulnerable (Morrongiello & Kiriakou, 2004). Our finding that poor affective involvement is related to low safety behaviors among mothers supports this interpretation. Perhaps the safety behaviors measured in the FSS tap those behaviors that the mothers could effectively change. Kronenfeld, Reiser, Glik, Alatorre, and Jackson (1997), reported direct effects and greater use of safety behaviors in mothers who had high stress levels and high coping skills (affect variables) and only an indirect effect for cognitive variables in increasing the use of safety behaviors.

Despite these limitations, the intervention increased use of safety behaviors and thus affected one part of the injury equation. Future research with high risk-taking populations and approaches that enhance the social/emotional milieu are necessary for further refinement of interventions. If some physical risk taking is a necessary social developmental experience in the context of peer play and risk engagement, then the very low rates of physical risk taking among overweight children suggest additional psychological issues that intervention programs to reduce sedentary activity and increase physical activity will have to address for health promotion.

In conclusion, Sommers (2006) suggests that four strategies are needed for nurses to build injury science: identification of individuals at risk, development of models to explain the association between risk taking and injury, development and testing of interventions to prevent and control injury, and refinement of interventions that are culturally relevant. The results of this study contribute to these goals to foster a child and family approach for nurses practicing in primary care and community settings.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institutes of Health (RO1 NR04680). Thank you to Annemarie Charlesworth-Suring MA, Project Director, and Ms. Emma Passalacqua BA, staff coordinator, of the Kids TV study.

Contributor Information

Christine Kennedy, Dept. of Family Health Care, School of Nursing, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, California.

Jyu-Lin Chen, Dept. of Family Health Care, School of Nursing, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, California.

References

- Bass JL, Mehta KA. Developmentally-oriented safety surveys: Reported parental and adolescent practices. Clinical Pediatrics. 1980;19(5):350–356. doi: 10.1177/000992288001900508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo LM. Parent-reported injury-associated behaviors and life events among injured, ill, and well preschool children. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 1996;11(2):100–110. doi: 10.1016/S0882-5963(96)80067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry D, Savoye M, Melkus G, Grey M. An intervention for multiethnic obese parents and overweight children. Applied Nursing Research. 2007;20(2):63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter KF, Kulbok PA. Evaluation of the interaction model of client health behavior through the first decade of research. ANS: Advances in Nursing Science. 1995;18(1):62–73. doi: 10.1097/00012272-199509000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JL, Kennedy C. Cultural variations in children’s coping behaviour, TV viewing time, and family functioning. International Nursing Review. 2005;52(3):186–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2005.00419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Kresnow MJ, Simon TR, Dellinger A. Injury-prevention counseling and behavior among US children: Results from the second Injury Control and Risk Survey. Pediatrics. 2007;119(4):e958–e965. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen P, Mikkelsen MR. Jumping off and being careful: Children’s strategies of risk management in everyday life. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2008;30(1):112–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox CL. The Health Self-Determinism Index. Nursing Research. 1985;34(3):177–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox CL, Cowell JM, Marion LN, Miller EH. The Health Self-Determinism Index for Children. Research in Nursing & Health. 1990;13(4):237–246. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770130406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein N, Baldwin L, Bishop S. The McMaster Family Assessment Device. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1983;9(2):171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Farrand L, Cox CL. Determinants of positive health behaviors in middle childhood. Nursing Research. 1993;42(4):208–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile DA, Walsh DA. A normative study of family media habits. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2002;23(2):157–178. [Google Scholar]

- Green J. Risk and the construction of social identity: Children’s talk about accidents. Sociology of Health & Illness. 1997;19(4):457–479. [Google Scholar]

- Grey M, Boland E, Davidson M, Li J, Tamborlane WV. Coping skills training for youth with diabetes mellitus has long-lasting effects on metabolic control and quality of life. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2000;137(1):107–113. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.106568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hester NO. Child’s health self-concept scale: Its development and psychometric properties. ANS: Advances in Nursing Science. 1984;7(1):45–55. doi: 10.1097/00012272-198410000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabakoff R, Miller I, Bishop D, Epstein N, Keitner G. A psychometric study of the McMaster Family Assessment Device in psychiatric, medical, and nonclinical samples. Journal of Family Psychology. 1990;3(4):431–439. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy CM. Television and young Hispanic children’s health behaviors. Pediatric Nursing. 2000a;26(3):283–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy C. Examining television as an influence on children’s health behaviors. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2000b;15(5):272–281. doi: 10.1053/jpdn.2000.8676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy C, Charlesworth A, Chen JL. Interactive data collection: Benefits of integrating new media into pediatric research. Computers, Informatics, Nursing. 2003;21(3):120–127. doi: 10.1097/00024665-200305000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy C, Charlesworth A, Chen JL, Wilkosz ME. Maternal health and family media use. 2008 Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy C, Floriani V. Translating research on healthy lifestyles for children: Meeting the needs of diverse populations. The Nursing Clinics of North America. 2008;43(3):397–417. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy CM, Lipsitt LP. Risk-taking in preschool children. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 1998;13(2):77–84. doi: 10.1016/S0882-5963(98)80034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy CM, Rodriguez DA. Risk taking in young Hispanic children. Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 1999;13(3 Pt 1):126–135. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5245(99)90074-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy CM, Strzempko F, Danford C, Kools S. Children’s perceptions of TV and health behavior effects. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2002;34(3):289–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2002.00289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronenfeld JJ, Reiser M, Glik DC, Alatorre C, Jackson K. Safety behaviors of mothers of young children: Impact of cognitive, stress and background factors. Health. 1997;1(2):205–225. [Google Scholar]

- Marin G, Sabogal F, Marin BV, Oter-Sabogal R, Perez-Stable EJ. Development of a short acculturation scale for Hispanics. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1987;9(2):183–205. [Google Scholar]

- Mason M, Christoffel KK, Sinacore J. Reliability and validity of The Injury Prevention Project Home Safety Survey. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2007;161(8):759–765. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.8.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller IW, Ryan CE, Keitner GI, Bishop DS, Epstein NB. The McMaster Approach to Families: Theory, assessment, treatment and research. Journal of Family Therapy. 2000;22(2):168–189. [Google Scholar]

- Morrongiello BA. Do children’s intentions to risk take relate to actual risk taking? Injury Prevention. 2004;10(1):62–64. doi: 10.1136/ip.2003.003624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrongiello BA, Kiriakou S. Mothers’ home-safety practices for preventing six types of childhood injuries: What do they do, and why? Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2004;29(4):285–297. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrongiello BA, Mark L. “Practice what you preach”: Induced hypocrisy as an intervention strategy to reduce children’s intentions to risk take on playgrounds. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2008;33(10):1117–1128. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn011. [Advance Access.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrongiello BA, Lassenby-Lessard J, Matheis S. Understanding children’s injury-risk behaviors: The independent contributions of cognitions and emotions. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;32(8):926–937. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts R, Doppler M, Hernandez M. Effects of television content on physical risk-taking in children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1994;58(3):321–331. doi: 10.1006/jecp.1994.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts R, Martinez IG, Dedmon A. Childhood risk taking and injury: Self-report and informant measures. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1995;20(1):5–12. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/20.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts R, Martinez IG, Dedmon A, Schwarz L, DiLillo D, Swisher L. Brief report: Cross-validation of the Injury Behavior Checklist in a school-age sample. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1997;22(4):533–540. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/22.4.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts R, Swisher L. Effects of televised safety models on children’s risk taking and hazard identification. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1998;23(3):157–163. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/23.3.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan-Wenger NM. Development and psychometric properties of the Schoolagers’ Coping Strategies Inventory. Nursing Research. 1990;39(6):344–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommers MS. Injury as a global phenomenon of concern in nursing science. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2006;38(4):314–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2006.00121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speltz ML, Gonzales N, Sulzbacher S, Quan L. Assessment of injury risk in young children: A preliminary study of the injury behavior checklist. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1990;15(3):373–383. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/15.3.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stember M, Swanson-Kaufman K, Goodwin L, Rogers S, Mathews S. How often do you? Denver, CO: University of Colorado Health Services Center; 1984. [Google Scholar]