Abstract

Purpose

Patients with cancer often experience comorbidities that may affect their prognosis and outcome. The objective of this study was to determine the effect of comorbidities on the survival of patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS).

Patients and Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of 600 consecutive patients with MDS who presented to MD Anderson Cancer Center from January 2002 to December 2004. The Adult Comorbidity Evaluation-27 (ACE-27) scale was used to assess comorbidities. Data on demographics, International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS), treatment, and outcome (leukemic transformation and survival) were collected. Kaplan-Meier methods and Cox regression were used to assess survival. A prognostic model incorporating baseline comorbidities with age and IPSS was developed to predict survival.

Results

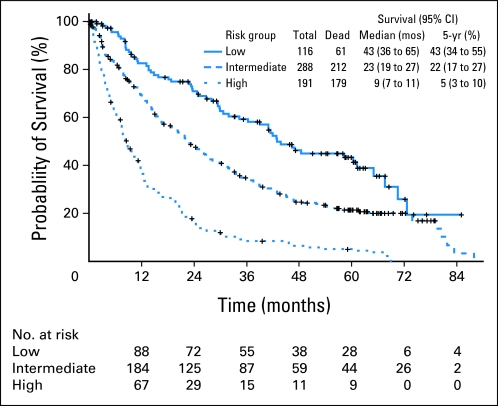

Overall median survival was 18.6 months. According to the ACE-27 categories, median survival was 31.8, 16.8, 15.2, and 9.7 months for those with none, mild, moderate, and severe comorbidities, respectively (P < .001). Adjusted hazard ratios were 1.3, 1.6, and 2.3 for mild, moderate, and severe comorbidities, respectively, compared with no comorbidities (P < .001). A final pognostic model including age, IPSS, and comorbidity score predicted median survival of 43.0, 23.0, and 9.0 months for lower-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups, respectively (P < .001).

Conclusion

Comorbidities have a significant impact on the survival of patients with MDS. Patients with severe comorbidity had a 50% decrease in survival, independent of age and IPSS risk group. A comprehensive assessment of the severity of comorbidities helps predict survival in patients with MDS.

INTRODUCTION

Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) comprises a group of clonal hematopoietic stem-cell disorders characterized by ineffective hematopoiesis and peripheral cytopenias. MDS is heterogeneous at both the clinical and molecular levels, and a significant fraction of patients experience transformation to acute myelogenous leukemia (AML).1,2 The incidence of MDS in the United States is not exactly known, but it is estimated that approximately three to four individuals per 100,000 are diagnosed with MDS every year.2 This increases with age, exceeding 20 per 100,000 persons in those older than 70 years.2 Overall, 70% of patients with MDS are older than 70 years of age.2

Three major classifications and prognostic systems are used in MDS: the French-American-British,3 the revised WHO classification,4 and the International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS).5 All three of these systems have limitations in predicting prognosis of patients with MDS. The French-American-British and the WHO are morphologic descriptions of the disease. The IPSS, although more comprehensive, has limitations in predicting outcome in patients with lower-risk disease and gives more weight to blast percentage compared with cytogenetics. Several new prognostic models have been developed recently, including the WHO classification–based prognostic scoring system,6 the global MD Anderson model,7 and a lower-risk specific model.8 However, none of the above prognostic scoring systems include comorbidities as part of risk assessment.

Patients with cancer often suffer from other comorbidities, which may exist before the diagnosis of cancer or may develop during the clinical course of malignancy.9 Comorbidities are of great significance because they are known to affect therapeutic plans and outcomes, including survival, in patients with cancer.10 Multiple studies of comorbidities have been conducted in patients with head and neck,11 prostate,12,13 breast,14 digestive system,15 gynecologic,16,17 and urinary system cancers.18 In general, outcome tends to be poorer in patients with comorbid ailments.19 Of importance, the impact of comorbidities has been studied as part of risk stratification in patients with AML and MDS receiving hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (SCT).20 However, information regarding the influence of comorbidities on the natural history of patients with MDS is limited.21 The purpose of this study was to evaluate the impact of the severity of comorbidities on overall survival (OS) in a large cohort of patients with MDS using the Adult Comorbidity Evaluation-27 (ACE-27), a comorbidity index for use in patients with cancer.22

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

We conducted a retrospective cohort study that included all adult patients with MDS who presented to MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) between January 2002 and December 2004. A total of 600 patients were reviewed. Information regarding comorbid ailments was extracted using the ACE-27, a validated 27-item comorbidity index for patients with cancer.22 Derived from the Kaplan-Feinstein Comorbidity Index, the ACE-27 categorizes specific diseases into one of three levels of comorbidity: grade 1 (mild), grade 2 (moderate), and grade 3 (severe), according to individual organ decompensation and prognostic impact. An overall comorbidity score (none, 0; mild, 1; moderate, 2; or severe, 3) is assigned based on the highest ranked/graded single ailment. In cases in which two or more moderate ailments occur in different organ systems or disease groupings, the overall comorbidity score is designated as severe.

In addition to demographic data that included age, sex, and race, we also collected information on each patient's date of presentation to MDACC and date of death or time of last follow-up. Specific staging information based on the IPSS, time to SCT, and leukemic transformation was also obtained. Data extraction was cross-checked for accuracy by two of the investigators (K.N., S.S.). The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at MDACC.

Statistical Analysis

The primary end point of this study was OS calculated in months from day of presentation to MDACC until death as a result of any cause. Observations were censored for patients last known to be alive. Descriptive statistics of the study population, including means (with corresponding standard deviations), medians (with corresponding ranges), and proportions, together with 95% CIs were computed. Association between each paired group was tested using χ2 test. Survival and hazard functions were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and survival between groups was compared using the two-sided log-rank test (log-rank test for trend only where ≥ three groups were entered in logical order, such as groups in IPSS and score). The multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to examine risk factors related to survival after adjusting for other factors. Risk factors included age, IPSS, and whether patients had experienced comorbidities by the ACE-27 as well as received one of the following treatments: supportive care (transfusions and/or growth factors), hypomethylating agents, chemotherapy, and experimental agents. The effect of therapy was studied for initial type of therapy. Interaction between comorbidity and baseline disease characteristics was analyzed. Significance was established at P < .05. Subgroup analyses were performed for each IPSS group as well as for age (≤ 65 years, > 65 years). A sensitivity analysis was also conducted, excluding patients who had undergone SCT. The χ2 test was used to test association between SCT and comorbidity. A risk score was developed based on regression coefficients from the final multivariate model. A prognostic model incorporating patient baseline comorbidity was thus derived according to risk scores. Statistical analyses were carried out using SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and S-Plus, version 7.0 (Insightful Corporation, Seattle, WA).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Six hundred patients with MDS were included in this study. Patient characteristics are listed in Appendix Table A1 (online only). Four hundred patients (66.7%) were male, and 518 (87.1%) were white. Median age at presentation was 66.6 years (range, 17.3 to 93.5 years). Mean duration of follow-up of living patients was 23.6 months, with a median follow-up of 14.8 months (range, 0 to 88 months). Median time from diagnosis to referral to MDACC was 0.8 months (range, 0 to 71.5 months). Approximately half of the patients had a baseline IPSS classification of low or intermediate 1. Of note, 183 patients (31%) had secondary MDS, and 120 (20%) had previously received chemotherapy or radiation therapy. One hundred twenty-three patients (20.5%) experienced leukemic transformation; 51 (8.5%) received SCT.

ACE-27 in MDS

Baseline ACE-27 comorbidity scores were as follows: none, 137 patients (22.8%); mild, 254 (42.3%); moderate, 127 (21.2%); and severe, 82 (13.7%). Approximately 55% of patients were diagnosed with disorder of the cardiovascular system, with hypertension being the most common comorbidity (37.0%) followed by coronary artery bypass graft (14.3%). History of prior malignancy was reported in 168 patients (28.0%). Ninety-seven patients (16.2%) had diabetes mellitus (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Comorbidities

| Comorbidity | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| ACE-27 score | ||

| None, 0 | 137 | 22.8 |

| Mild, 1 | 254 | 42.3 |

| Moderate, 2 | 127 | 21.2 |

| Severe, 3 | 82 | 13.7 |

| System | ||

| Cardiovascular | 328 | 54.7 |

| Endocrine | 97 | 16.2 |

| GI | 40 | 6.7 |

| Immunologic | 1 | 0.2 |

| Malignancy | 168 | 28.0 |

| Neurologic | 35 | 5.8 |

| Obesity | 1 | 0.2 |

| Psychiatric | 48 | 8.0 |

| Renal | 14 | 2.3 |

| Respiratory | 53 | 8.8 |

| Rheumatologic | 17 | 2.8 |

| Substance abuse | 32 | 5.3 |

Abbreviation: ACE-27, Adult Comorbidity Evaluation-27.

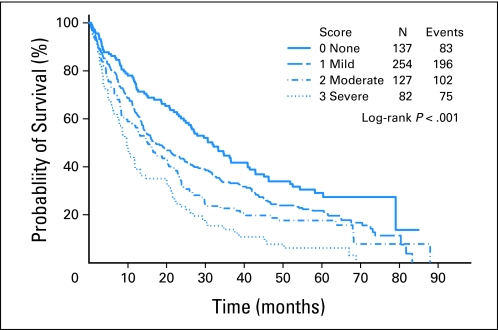

Comorbidities and Survival

A total of 456 patients (76.0%) died during follow-up; median survival was 18.6 months. Median survival according to ACE-27 score was: 31.8 months, no comorbidities; 16.8 months, mild; 15.2 months, moderate; and 9.7 months, severe (P < .001; Table 2; Fig 1). History of malignancy or cardiovascular disease was associated with worst survival. The median survival time was 10.6 and 23.5 months for patients with and without a history of malignancy, respectively (P < .001). The median survival time was 14.4 and 23.7 months for patients with and without cardiovascular disease, respectively (P < .001). Survival according to other covariates of interest is listed in Appendix Table A2 (online only). Older age, advanced IPSS, and leukemic transformation were associated with greater risk of death, whereas having undergone SCT was associated with longer survival. Neither sex nor race seemed to affect survival. Initial treatment involving supportive care (transfusion and/or growth factors), hypomethylating agents, chemotherapy, and experimental agents did not have an effect on survival (P = .53).

Table 2.

Association of Patient and Disease Characteristics With Survival

| Variable | Total No. of Patients | Death |

Median Survival(months) | P (univariate) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | ||||

| ACE-27 score | < .001 | ||||

| None, 0 | 137 | 83 | 60.6 | 31.8 | |

| Mild, 1 | 254 | 196 | 77.2 | 16.8 | |

| Moderate, 2 | 127 | 102 | 80.3 | 15.2 | |

| Severe, 3 | 82 | 75 | 91.5 | 9.7 | |

| Age, years | < .001 | ||||

| ≤ 65 | 254 | 169 | 66.5 | 27.9 | |

| > 65 | 346 | 287 | 82.9 | 14.1 | |

| Sex | .43 | ||||

| Male | 400 | 315 | 78.8 | 17.6 | |

| Female | 200 | 141 | 70.5 | 19.9 | |

| Race | .11 | ||||

| White | 518 | 392 | 75.7 | 19.1 | |

| Non-white | 77 | 60 | 77.9 | 13.3 | |

| SCT | < .001 | ||||

| No | 549 | 431 | 78.5 | 16.0 | |

| Yes | 51 | 25 | 49.0 | 65.1 | |

| IPSS | < .001 | ||||

| Low | 80 | 47 | 58.8 | 33.6 | |

| Intermediate 1 | 216 | 152 | 70.4 | 25.9 | |

| Intermediate 2 | 173 | 144 | 83.2 | 14.0 | |

| High | 126 | 109 | 86.5 | 8.7 | |

| Regimen | .53 | ||||

| Supportive care | 280 | 200 | 71.4 | 16.6 | |

| Hypomethylating | 69 | 50 | 72.5 | 27.9 | |

| Chemotherapy | 125 | 105 | 84.0 | 16.0 | |

| Experimental | 126 | 101 | 80.2 | 16.2 | |

Abbreviations: ACE-27, Adult Comorbidity Evaluation-27; IPSS, International Prognostic Scoring System; SCT, stem-cell transplantation.

Fig 1.

Survival curves by Adult Comorbidity Evaluation-27 (ACE-27) comorbidity score. Each line represents survival according to ACE-27 score. Patients with no comorbidity (ACE-27 score, 0; solid blue line) have the longest survival, whereas those with severe comorbidity (ACE-27 score, 3; dotted blue line) have the shortest survival.

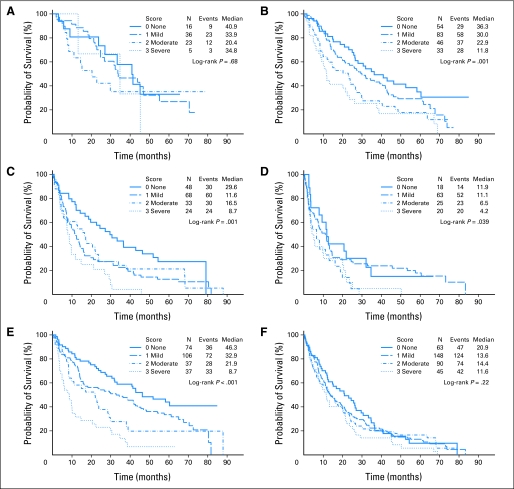

We determined median survival by IPSS; patients in the low-risk category had a median survival of 33.6 months, whereas the median survival of the high-risk group was 8.7 months (P < .001). We conducted a subgroup analysis examining survival curves by ACE-27 comorbidity score for each IPSS category individually (Figs 2A to 2D). Comorbidity did not have a significant effect on survival for patients in the low-risk category (P = .68), whereas patients in the intermediate-1 and -2 groups (P = .001) and high-risk category (P = .04) had significantly worse survival with increasing ACE-27 score. Patients younger than 65 years had longer median survival than those older than 65 years (27.9 v 14.4 months; P < .001). Although comorbidities significantly decreased survival in those younger than 65 years (P < .001), they had no significant effect in those older than 65 years (P = .22; Figs 2E to 2F).

Fig 2.

Survival curves by comorbidity score and (A, B, C, D) International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS). (A) Low IPSS score; (B) intermediate-1 IPSS score; (C) intermediate-2 IPSS score; (D) high IPSS score. (E, F) Survival curves by comorbidity score and age. (E) Age 65 years or younger; (F) older than age 65 years.

Comorbidities and Risk of Transformation

A total of 123 patients (20.5%) experienced transformation to AML. There was no significant association between severity of comorbidity and leukemic transformation (P = .55).

Comorbidities and SCT

Of the 51 patients who had SCT after their initial therapy at MDACC, 24 (47.1%) died. A significant inverse linear trend was observed between severity of comorbidity and having received SCT (P < .001), with patients with milder comorbidity being more likely to receive SCT. Patients who received SCT had a median survival of 65 months, whereas those who did not receive SCT had a survival of only 16 months. However, baseline comorbidity continued to have a significant impact on the survival of patients irrespective of their SCT status.

Multivariate Analyses Incorporating Comorbidities in MDS

We conducted multivariate analyses using Cox proportional hazards model (Table 3). Because SCT had a significant effect on survival, we performed two sets of models, with and without, including patients with SCT. The results listed in Appendix Table A3 (online only) include all patients (with and without SCT) and show the univariate and multivariate hazard ratios for the covariates of interest that were statistically significant and therefore included in final model: age, IPSS, and ACE-27 comorbidity score. After adjustment, hazard ratios were 1.3, 1.6, and 2.3 for mild, moderate, and severe scores, respectively, compared with no comorbidities. When we excluded those who underwent SCT in the models, patients with moderate and severe comorbidity scores continued to do worse, with a hazard ratio of 1.5 and 2.1, respectively. Secondary or therapy-related MDS was not significant in the model (data not shown). We also evaluated the effect of different therapies (supportive care, hypomethylating agents, investigational chemotherapies, chemotherapy). The prognostic model was able to segregate three risk levels for each therapy (for each group, overall P < .001; data not shown).

Table 3.

Final Multivariate Survival Model and Risk Score

| Prognostic Factor | Coefficient | Score* |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| > 65 | 0.582 | 2 |

| Comorbidity (ACE-27) | ||

| Mild or moderate | 0.301 | 1 |

| Severe | 0.782 | 3 |

| IPSS | ||

| Intermediate 2 | 0.512 | 2 |

| High | 0.769 | 3 |

Abbreviations: ACE-27, Adult Comorbidity Evaluation-27; IPSS, International Prognostic Scoring System.

Score points were obtained by dividing estimated coefficients by 0.3.

Building a Prognostic Model That Includes Comorbidities

To obtain a clinically applicable prognostic model by incorporating the impact of comorbidites on survival, we assigned a score to each significant factor by dividing respective coefficients from the final multivariate model by 0.3 and rounding to the nearest integer (Fig 3). The final prognostic model for OS was thus developed as low (score 0 to 1), intermediate (score 2 to 4), and high (score 5 to 8). The model predicted survival on the entire patient group, as shown in Figure 3. Patients in the low-risk category had a median survival of 43.0 months versus 23.0 and 9.0 months for those in the intermediate- and high-risk groups, respectively (P < .001). Survival for each specific score is shown in Figure 3. The proposed model predicted well for survival regardless of whether patients received SCT subsequently (not shown).

Fig 3.

Survival curves by proposed risk model for all patients. Risk groups are represented by three different lines, with those in the low-risk category having the longest survival (43 months) compared with those in the high-risk category (9 months).

DISCUSSION

We conducted a retrospective cohort study to evaluate the impact of comorbidities on the OS of patients with MDS. We used the ACE-27, an instrument specifically designed for patients with cancer, to measure the severity of comorbidities. Our results show that increasing comorbidity has a significant independent effect on the survival of these patients, after adjusting for age and IPSS. Patients with high ACE-27 comorbidity scores had double the risk of death than those with no comorbidities, after adjustment.

Comorbidities and their impact on the survival of patients with cancer have been widely studied in patients with solid tumor malignancies, showing an adverse relationship between the severity of comorbid ailments and survival.19 Information on comorbidity and MDS is still sparse, and most of the research to date pertains to patients undergoing SCT. Wang et al21 recently conducted a population-based study of older persons with MDS that suggested lower survival in those with comorbid ailments, particularly those with congestive heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Moreover, previous studies have shown congestive heart failure, pulmonary and liver failure, infections, hemorrhage, and solid tumors to be main causes of nonleukemic death in MDS.23–25 In our analysis, 37.0% of patients had hypertension, making it the most common comorbidity, whereas history of solid malignancy was associated with worst survival, with a hazard ratio of 1.6 adjusted for age, IPSS, and cardiovascular diseases.

Several indices and instruments have been proposed to study the impact of comorbidities on index diseases. We used the ACE-27. To our knowledge, this is the first study that has used the ACE-27 in MDS. The ACE-27 was developed by Piccirillo et al22 and was derived from adult patients with cancer. The authors selected comorbidities of interest based on frequency of occurrence in patients with newly diagnosed cancer and made modifications to the Kaplan-Feinstein comorbidity index.26 The ACE-27 includes a greater number of important comorbid conditions like hypertension, cardiac arrhythmias, and alcohol abuse, which have been clearly shown to affect survival. It also grades the severity of illnesses such as myocardial infarction and congestive heart failure, which have also been shown to predict survival.

It is generally considered that the aggressive nature of the primary disease dictates clinical outcome in this patient population.27 In this study, concomitant comorbidity had a significant effect on mortality. Patients in the severe ACE-27 category had the worst prognosis, with a median survival of 9.7 months (P < .001), independent of age and IPSS. Interestingly, an interaction was observed between IPSS and comorbidity. As expected, IPSS was a strong predictor of survival. Comorbidities had a statistically significant adverse effect on survival in the intermediate-1 and -2 risk groups as well as in the high-risk group but no clear trend for those in the low-risk IPSS category. This finding is in contrast with studies that have shown host-related parameters like comorbid ailments and performance status to predict clinical outcome in low-risk disease, and it may be partially explained by the relatively smaller sample size, particularly of those with severe comorbidity in the low-risk IPSS category.

As expected, we also found older age and advanced IPSS to be associated with poor survival. When adjusted for IPSS and comorbidity score, patients with MDS older than 65 years were found to be at 63.0% greater risk of dying. These findings were consistent with those of Stauder et al.27,28 The IPSS does not include age. That said, it should be acknowledged that IPSS allows the calculation of survival based on patient age.5 In the WHO classification–based prognostic scoring system,6 age has a significant negative effect on the OS of patients in the low-risk group. In our study, increasing comorbidity failed to show a significant difference in survival in those older than 65 years of age. This finding increased the relevance of age alone in predicting prognosis in the older population.

These findings led us to develop a prognostic model that includes the three major predictors of survival in MDS: age, IPSS, and baseline comorbidities. On the basis of their risk scores, patients were categorized into three groups: low (score 0 to 1), intermediate (2 to 4), and high (5 to 8). Leukemic transformation was also studied, and no correlation was found between leukemic evolution and severity of comorbidity.

The current analysis was not designed to evaluate the effect of comorbidities on SCT. None of the 600 patients had received SCT as primary therapy. That said, patients who eventually underwent SCT had better OS than those who did not. A significant trend was noted between the number of patients undergoing SCT and the severity of comorbidity score. Only 3.7% of patients with a severe comorbidity score underwent SCT compared with 19.0% in the no-comorbidity category.

One major limitation of our study is its retrospective nature; it relies on accuracy of written records. There is also a possibility of abstractor bias because the study did not blind the abstractors from survival information. However, this bias was limited because all records were double checked and scored by two independent reviewers, who then agreed on discrepancies. Second, because our institution is mainly a referral center, we could not control for the time that elapsed between diagnosis and presentation to our cancer center. Hence, the survival time presented in our analysis is probably shorter than what we would expect if the analysis had been performed from initial presentation. It should be noted that the referral bias should not influence the conclusion because significant characteristics were evaluated in the context of IPSS. Third, our study was directed toward all-cause mortality and not MDS-related versus other specific disease mortality. We elected to report all-cause mortality because it is difficult to ascertain specific cause of death. For instance, a patient might die as a result of congestive heart failure, exacerbated by anemia, a well-known complication of MDS, thus rendering attribution difficult. Finally, although treatment did not seem to have an impact on survival, our study was not designed to specifically address the effects of treatment. Patients with comorbidities may have been less likely to receive aggressive therapy (confounding by indication), with subsequent deleterious effect on their survival. Of interest, the effect of comorbidity was more prominent in younger patients. Finally, it should be noted that a significant fraction of patients in this study had a history of prior malignancy, and this was associated with poor prognosis. Neither therapy-related nor secondary MDS was included in the model. This is in line with previous results from MDACC.7 It should be noted that secondary MDS is not part of IPSS.5 These data indicate that worse outcome is not necessarily related to a more aggressive type of MDS. Second, the prevalence of having both a history of malignancy and MDS suggests a potential link between the disorders. In summary, this study shows that concomitant comorbidity has a significant impact on the survival of patients with MDS and that comorbidity assessment needs to be part of new prognostic models.

Appendix

Table A1.

Patient Characteristics

| Characteristic | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| Median | 65.4 | |

| Range | 17-93 | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 400 | 66.7 |

| Race | ||

| White | 518 | 87.1 |

| IPSS | ||

| Low | 80 | 13.4 |

| Intermediate 1 | 216 | 36.3 |

| Intermediate 2 | 173 | 29.1 |

| High | 126 | 21.2 |

| Leukemic transformation | 477 | 79.5 |

| Stem-cell transplantation | 51 | 8.5 |

| Hgb, g/dL | ||

| Median | 9.8 | |

| Range | 4.5-16.4 | |

| Platelet count, k/uL | ||

| Median | 66 | |

| Range | 1-830 | |

| WBC, k/uL | ||

| Median | 3.8 | |

| Range | 0.5-99 | |

| BM blasts, % | ||

| Median | 6 | |

| Range | 0-29 | |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | ||

| Median | 1.0 | |

| Range | 0.4-5.7 | |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | ||

| Median | 0.7 | |

| Range | 0.1-3.8 | |

| Cytogenetics | ||

| Diploid | 282 | 47 |

| −5/−7 | 121 | 20 |

| Other | 175 | 29 |

| IM/ND | 20 | 3 |

Abbreviations: BM, bone marrow; Hgb, hemoglobin; IM, insufficient metaphases; IPSS, International Prognostic Scoring System; ND, not done.

Table A2.

Median Survival by Kaplan-Meier Estimate for Comorbidity and Other Covariates

| Variable | Total No. of Patients | Death |

Median Survival (months) | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | ||||

| Cardiovascular | < .001† | ||||

| No | 272 | 187 | 68.8 | 23.7 | |

| Yes | 328 | 269 | 82.0 | 14.4 | |

| Endocrine | .06 | ||||

| No | 503 | 377 | 75.0 | 19.6 | |

| Yes | 97 | 79 | 81.4 | 13.6 | |

| GI | .07 | ||||

| No | 560 | 421 | 75.2 | 19.1 | |

| Yes | 40 | 35 | 87.5 | 12.6 | |

| Immunologic | .52 | ||||

| No | 599 | 455 | 76.0 | 18.8 | |

| Yes | 1 | 1 | 100.0 | 12.8 | |

| Malignancy | < .001† | ||||

| No | 432 | 306 | 70.8 | 23.5 | |

| Yes | 168 | 150 | 89.3 | 10.6 | |

| Neurologic | .30 | ||||

| No | 565 | 425 | 75.2 | 18.6 | |

| Yes | 35 | 31 | 88.6 | 18.9 | |

| Obesity | .60 | ||||

| No | 599 | 456 | 76.1 | 18.6 | |

| Yes | 1 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Psychiatric | .74 | ||||

| No | 552 | 420 | 76.1 | 18.2 | |

| Yes | 48 | 36 | 75.0 | 19.4 | |

| Renal | .02† | ||||

| No | 586 | 442 | 75.4 | 18.9 | |

| Yes | 14 | 14 | 100.0 | 10.7 | |

| Respiratory | .70 | ||||

| No | 547 | 415 | 75.9 | 18.8 | |

| Yes | 53 | 41 | 77.4 | 14.6 | |

| Rheumatologic | .58 | ||||

| No | 583 | 444 | 76.2 | 18.8 | |

| Yes | 17 | 12 | 70.6 | 13.6 | |

| Substance abuse | .60 | ||||

| No | 568 | 430 | 75.7 | 18.8 | |

| Yes | 32 | 26 | 81.3 | 15.8 | |

| Age, years | < .001† | ||||

| ≤ 65 | 254 | 169 | 66.5 | 27.9 | |

| > 65 | 346 | 287 | 82.9 | 14.1 | |

| Sex | .43 | ||||

| Male | 400 | 315 | 78.8 | 17.6 | |

| Female | 200 | 141 | 70.5 | 19.9 | |

| Race | .11 | ||||

| White | 518 | 392 | 75.7 | 19.1 | |

| Non-white | 77 | 60 | 77.9 | 13.3 | |

| SCT | < .001† | ||||

| No | 549 | 431 | 78.5 | 16.0 | |

| Yes | 51 | 25 | 49.0 | 65.1 | |

| Leukemic transformation | .001† | ||||

| No | 477 | 340 | 71.3 | 20.6 | |

| Yes | 123 | 116 | 94.3 | 15.6 | |

| IPSS | < .001† | ||||

| Low | 80 | 47 | 58.8 | 33.6 | |

| Intermediate 1 | 216 | 152 | 70.4 | 25.9 | |

| Intermediate 2 | 173 | 144 | 83.2 | 14.0 | |

| High | 126 | 109 | 86.5 | 8.7 | |

| Regimen | .53 | ||||

| Supportive care | 280 | 200 | 71.4 | 16.6 | |

| Hypomethylating | 69 | 50 | 72.5 | 27.9 | |

| Chemotherapy | 125 | 105 | 84.0 | 16.0 | |

| Experimental | 126 | 101 | 80.2 | 16.2 | |

Abbreviations: IPSS, International Prognostic Scoring System; SCT, stem-cell transplantation.

P values from univariate log-rank test.

P < .05.

Table A3.

Cox Proportional Hazards Model With Factors Predicting Survival

| Parameter* | Univariate |

Multivariate |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |

| Age, years | ||||||

| > 65 v ≤ 65 | 1.7 | 1.4 to 2.1 | < .001† | 1.6 | 1.3 to 2.0 | < .001† |

| IPSS | ||||||

| Intermediate 1 v low | 1.3 | 0.9 to 1.7 | .17 | 1.3 | 0.9 to 1.8 | 0.15 |

| Intermediate 2 v low | 1.8 | 1.3 to 2.5 | < .001† | 2.0 | 1.4 to 2.8 | < .001† |

| High v low | 2.6 | 1.8 to 3.6 | < .001† | 2.5 | 1.8 to 3.6 | < .001† |

| Comorbidity score | ||||||

| Mild v none | 1.4 | 1.1 to 1.8 | .01† | 1.3 | 1.0 to 1.7 | .04† |

| Moderate v none | 1.7 | 1.3 to 2.3 | < .001† | 1.6 | 1.2 to 2.1 | .004† |

| Severe v none | 2.5 | 1.8 to 3.4 | < .001† | 2.3 | 1.6 to 3.1 | < .001† |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; IPSS, International Prognostic Scoring System.

Analysis by comorbidity scores.

P < .05.

Footnotes

Supported in part by the Houston Center for Education and Research on Therapeutics, funded by the Agency for Health Quality and Research (Grant No. U18 HS016093); by a K24 career award from the National Institute for Arthritis, Musculoskeletal and Skin Disorders (M.E.S.-A.); and by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas, the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, and Grants No. 1RCTCA147431-01 and 5PO1CA108631-05 from the National Institutes of Health (G.G.-M.).

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Kiran Naqvi, Guillermo Garcia-Manero, Maria E. Suarez-Almazor

Financial support: Maria E. Suarez-Almazor

Administrative support: Guillermo Garcia-Manero, Maria E. Suarez-Almazor

Provision of study materials or patients: Guillermo Garcia-Manero, Sherry Pierce, Hagop M. Kantarjian, Maria E. Suarez-Almazor

Collection and assembly of data: Kiran Naqvi, Guillermo Garcia-Manero, Sagar Sardesai, Jeong Oh, Carlos E. Vigil, Sherry Pierce, Xiudong Lei, Maria E. Suarez-Almazor

Data analysis and interpretation: Kiran Naqvi, Guillermo Garcia-Manero, Sagar Sardesai, Jeong Oh, Sherry Pierce, Xiudong Lei, Jianqin Shan, Maria E. Suarez-Almazor

Manuscript writing: Kiran Naqvi, Guillermo Garcia-Manero, Sagar Sardesai, Jeong Oh, Carlos E. Vigil, Sherry Pierce, Xiudong Lei, Jianqin Shan, Hagop M. Kantarjian, Maria E. Suarez-Almazor

Final approval of manuscript: Kiran Naqvi, Guillermo Garcia-Manero, Sagar Sardesai, Jeong Oh, Carlos E. Vigil, Sherry Pierce, Xiudong Lei, Jianqin Shan, Hagop M. Kantarjian, Maria E. Suarez-Almazor

REFERENCES

- 1.Tefferi A, Vardiman JW. Myelodysplastic syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1872–1885. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0902908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rollison DE, Howlader N, Smith MT, et al. Epidemiology of myelodysplastic syndromes and chronic myeloproliferative disorders in the United States, 2001-2004, using data from the NAACCR and SEER programs. Blood. 2008;112:45–52. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-134858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett JM, Catovsky D, Daniel MT, et al. Proposals for the classification of the myelodysplastic syndromes. Br J Haematol. 1982;51:189–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vardiman JW, Thiele J, Arber DA, et al. The 2008 revision of the WHO classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia: Rationale and important changes. Blood. 2009;114:937–951. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-209262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenberg P, Cox C, LeBeau MM, et al. International scoring system for evaluating prognosis in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 1997;89:2079–2088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malcovati L, Germing U, Kuendgen A, et al. Time-dependent prognostic scoring system for predicting survival and leukemic evolution in myelodysplastic syndromes. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3503–3510. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.5696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kantarjian H, O'Brien S, Ravandi F, et al. Proposal for a new risk model in myelodysplastic syndrome that accounts for events not considered in the original International Prognostic Scoring System. Cancer. 2008;113:1351–1361. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia-Manero G, Shan J, Faderl S, et al. A prognostic score for patients with lower risk myelodysplastic syndrome. Leukemia. 2008;22:538–543. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2405070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feinstein AR. The pre-therapeutic classification of comorbidity in chronic disease. J Chronic Dis. 1970;23:455–469. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(70)90054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Extermann M. Measurement and impact of comorbidity in older cancer patients. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2000;35:181–200. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(00)00090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Piccirillo JF. Importance of comorbidity in head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:593–602. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200004000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albertsen PC, Fryback DG, Storer BE, et al. The impact of co-morbidity on life expectancy among men with localized prostate cancer. J Urol. 1996;156:127–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clemens JD, Feinstein AR, Holabird N, et al. A new clinical-anatomic staging system for evaluating prognosis and treatment of prostatic cancer. J Chronic Dis. 1986;39:913–928. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(86)90040-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yancik R, Wesley MN, Ries LA, et al. Effect of age and comorbidity in postmenopausal breast cancer patients aged 55 years and older. JAMA. 2001;285:885–892. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.7.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yancik R, Wesley MN, Ries LA, et al. Comorbidity and age as predictors of risk for early mortality of male and female colon carcinoma patients: A population-based study. Cancer. 1998;82:2123–2134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DiSilvestro P, Peipert JF, Hogan JW, et al. Prognostic value of clinical variables in ovarian cancer. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:501–505. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wells CK, Stoller JK, Feinstein AR, et al. Comorbid and clinical determinants of prognosis in endometrial cancer. Arch Intern Med. 1984;144:2004–2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller DC, Taub DA, Dunn RL, et al. The impact of co-morbid disease on cancer control and survival following radical cystectomy. J Urol. 2003;169:105–109. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piccirillo JF, Tierney RM, Costas I, et al. Prognostic importance of comorbidity in a hospital-based cancer registry. JAMA. 2004;291:2441–2447. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.20.2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sorror ML, Maris MB, Storb R, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT)-specific comorbidity index: A new tool for risk assessment before allogeneic HCT. Blood. 2005;106:2912–2919. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang R, Gross CP, Halene S, et al. Comorbidities and survival in a large cohort of patients with newly diagnosed myelodysplastic syndromes. Leuk Res. 2009;33:1594–1598. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Piccirillo JF, Costas I, Claybour P, et al. The measurement of comorbidity by cancer registries. J Registry Manag. 2003;30:8–14. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malcovati L, Porta MG, Pascutto C, et al. Prognostic factors and life expectancy in myelodysplastic syndromes classified according to WHO criteria: A basis for clinical decision making. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7594–7603. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.7038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Della Porta MG, Malcovati L. Clinical relevance of extra-hematologic comorbidity in the management of patients with myelodysplastic syndrome. Haematologica. 2009;94:602–606. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.005702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dayyani F, Conley AP, Strom SS, et al. Cause of death in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndrome. Cancer. 2010;116:2174–2179. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaplan MH, Feinstein AR. The importance of classifying initial co-morbidity in evaluatin the outcome of diabetes mellitus. J Chronic Dis. 1974;27:387–404. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(74)90017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stauder R, Nösslinger T, Pfeilstöcker M, et al. Impact of age and comorbidity in myelodysplastic syndromes. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2008;6:927–934. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2008.0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pfeilstöcker M, Karlic H, Nösslinger T, et al. Myelodysplastic syndromes, aging, and age: Correlations, common mechanisms, and clinical implications. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:1900–1909. doi: 10.1080/10428190701534382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]