Abstract

Purpose

Prostate-specific antigen screening has led to enormous overtreatment of prostate cancer because of the inability to distinguish potentially lethal disease at diagnosis. We reasoned that by identifying an mRNA signature of Gleason grade, the best predictor of prognosis, we could improve prediction of lethal disease among men with moderate Gleason 7 tumors, the most common grade, and the most indeterminate in terms of prognosis.

Patients and Methods

Using the complementary DNA–mediated annealing, selection, extension, and ligation assay, we measured the mRNA expression of 6,100 genes in prostate tumor tissue in the Swedish Watchful Waiting cohort (n = 358) and Physicians' Health Study (PHS; n = 109). We developed an mRNA signature of Gleason grade comparing individuals with Gleason ≤ 6 to those with Gleason ≥ 8 tumors and applied the model among patients with Gleason 7 to discriminate lethal cases.

Results

We built a 157-gene signature using the Swedish data that predicted Gleason with low misclassification (area under the curve [AUC] = 0.91); when this signature was tested in the PHS, the discriminatory ability remained high (AUC = 0.94). In men with Gleason 7 tumors, who were excluded from the model building, the signature significantly improved the prediction of lethal disease beyond knowing whether the Gleason score was 4 + 3 or 3 + 4 (P = .006).

Conclusion

Our expression signature and the genes identified may improve our understanding of the de-differentiation process of prostate tumors. Additionally, the signature may have clinical applications among men with Gleason 7, by further estimating their risk of lethal prostate cancer and thereby guiding therapy decisions to improve outcomes and reduce overtreatment.

INTRODUCTION

Widespread use of prostate-specific antigen levels for screening has led to a large increase in the incidence of diagnosed prostate cancer and its treatment.1 The overtreatment of prostate cancer is widely recognized; recent randomized trial data suggest that 48 men must be treated to prevent a single prostate cancer–specific death.2 A principal difficulty in preventing overtreatment is our current inability to distinguish at diagnosis with sufficient confidence the men who will have an indolent course of disease from those who have aggressive disease. With more than 200,000 cases of prostate cancer diagnosed3 and 168,000 prostatectomies4 each year in the United States, there is an acute need to improve the ability to distinguish potentially lethal from indolent disease. Several groups, including our own, have used mRNA expression profiling in an attempt to construct a molecular signature of lethal disease.5,6 In a variety of analyses, our group developed signatures that predicted lethal disease with a high degree of statistical significance but did not substantially improve on models that included known clinical predictors.5

Apart from stage, currently the strongest predictor of lethal prostate cancer is Gleason grade,7 a measure of the degree of differentiation of prostate tumor cells; the sum of the primary (predominant) Gleason pattern (1 to 5) and the secondary pattern (1 to 5) is the Gleason score, which ranges from 2 to 10. In a study using re-reviewed Gleason score from prostatectomy specimens, those with a Gleason score of 8 had a hazard of lethal cancer (dying from prostate cancer or developing distant metastases) that was 7.4 (95% CI, 2.5 to 22) times higher than those with Gleason 3 + 4; patients with a Gleason score of 9 to 10 had an even higher risk of lethal cancer (hazard ratio, 19.1; 95% CI, 7.4 to 49.7).8 Currently, most men present with apparently low-risk disease, with low tumor volume, and with intermediate Gleason scores of 6 or 7.

Since Gleason grade is such a powerful predictor of lethal disease, we sought an alternative approach to outcome prediction. We reasoned that a molecular signature that discriminates poorly from well-differentiated tumors defined by Gleason grade might improve prediction of lethal disease and provide insight into the biologic mechanisms underlying the strong relation of Gleason grade and disease progression.

Our work builds on previous studies9–15 in which molecular signatures and pathways based on mRNA expression can distinguish tumors according to Gleason grade. However, these past studies were based on small numbers of patients with prostate cancer, the methods and signatures from one study are usually not replicated in another and, importantly, they were not examined with respect to lethal outcomes. In this study, we apply complementary analytic methods to develop and validate an mRNA signature to distinguish high from low Gleason scores in two large, well-characterized cohorts: the Swedish Watchful Waiting Cohort16–18 and the Physicians' Health Study (PHS).19,20 We then applied the results to determine whether the signature could improve the prediction of lethal outcomes in men with Gleason grade 7.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Populations

The expression profiling data in this study were part of a project to identify molecular signatures of lethal and indolent prostate cancer and therefore included men who died from prostate cancer during follow-up (lethal prostate cancer) or who survived at least 10 years after diagnosis (men with indolent prostate cancer).5

Swedish Cohort

The population-based Swedish Watchful Waiting cohort consisted of men diagnosed with incidental prostate cancer discovered through transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) or adenoma enucleation (ie, stage T1a-b) in the Uppsala-Örebro (1977–1994) and South East (1987–1999) Health Care Regions of Sweden.16–18 Eligible patients were identified through population-based prostate cancer databases. In accordance with prevailing standards, patients were followed expectantly. No prostate-specific antigen screening programs were then in place. The archival TURP specimens were identified, and we included in the expression array patients with high-density tumor regions (more than 90% tumor cells) and high-quality expression data (n = 358).

PHS

We included samples from men with histologically confirmed prostate cancer who were participants in the PHS,19,20 a randomized trial of aspirin and micronutrients in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer among healthy US physicians. We have developed an archival repository of tumor specimens from radical prostatectomy (RP) or TURP. For the expression profiling, we selected 116 (RP, n = 102; TURP, n = 14) patients with high-density tumor area and included only those with high-quality expression data in this analysis (n = 109).

Gleason Grade Re-Review

We conducted a standardized review of the original hematoxylin and eosin slides from referring hospitals and assigned a primary and secondary Gleason grade.8 The review was conducted blinded to the original pathology reports and any clinical data.

RNA Extraction and Profiling

A pathologist identified regions that were more than 90% tumor. Cores were taken and deparaffinized; then RNA was extracted as previously described.21 Four complementary DNA–mediated annealing, selection, extension, and ligation assay panels were designed for the Illumina platform (Illumina; San Diego, CA) for the discovery of molecular signatures relevant to prostate cancer, as previously described.21 The final array consisted of 6,100 genes. The annealing, selection, extension, and ligation assay was found to be well-suited for formalin-fixed tissue22 and provides good correlation with other standard methods, such as quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR).

Quality assessment was performed assuming a log-normal distribution of 27control probes present within. We compared each gene measurement with this negative control distribution, considering a gene “present” if its expression level was above the 95th percentile. For each sample, we computed the proportion of present genes. We excluded poor-quality samples with less than 55% present measurements. The remaining raw data were normalized by using a cubic spline algorithm. This procedure was adapted from Hoshida et al.23

Statistical Analysis

We compared men with both Gleason patterns ≤ 3 (“Gleason ≤ 6”) with men who had both patterns ≥ 4 (“Gleason ≥ 8”) to provide a sharp contrast between high and low Gleason scores, leaving out men with Gleason 7 for later testing (see below).

First, in each cohort, we performed a t test for each of the 6,100 genes to distinguish low grade from high grade. We determined whether the top genes among those in the Swedish cohort were enriched among the those in the PHS by cross classifying genes according to whether or not they were in the top 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, or 25% of each, calculating a χ2 test statistic for each 2 × 2 table, and taking the largest of these; the P value was calculated by permutation.

Pooling the cohorts, we ran a gene set enrichment analysis24,25 using 440 prespecified pathways from the Broad Institute's curated gene sets26 to identify pathways enriched in either the high- or low-grade tumors.

We used the prediction analysis of microarrays (PAM) R package27 to construct and validate a model predicting high-grade cancer. This method is an adaptation of a nearest neighbor classification method that considers models with different numbers of genes. First, we restricted our analysis to the Swedish data set (ie, the training data set). We selected an optimal model in the Swedish data by considering cross-validated prediction error and parsimony. Then we applied this model to the validation data set (PHS) and observed the misclassification. We visualized the differences in expression patterns between the two Gleason phenotypes by plotting individuals' scores along the first two principal components of the genes in this model, labeled by phenotype. We fit logistic regression models predicting lethal prostate cancer from these two principal components, among the Gleason ≤ 6 and the Gleason ≥ 8 separately to see whether overall differences in expression patterns correlated with lethal outcomes.

Finally, we calculated the model's predicted probabilities for poorly versus well-differentiated tumors for men with Gleason 7 tumors, who were not included in the training or validation sets. We sought to determine the model's ability to discriminate Gleason 4 + 3 from 3 + 4 and whether the molecular signature could improve prediction of lethal outcomes among men with Gleason 7 using logistic regression.

All analyses were performed with SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and the R package. This study is compliant with ethical committees at the University of Örebro and the institutional review board of Partners HealthCare.

RESULTS

Clinical characteristics of the Swedish and PHS cohorts are provided in Table 1, and further details of each Gleason phenotype are provided in Table 2. All of the patients in the Swedish cohort were diagnosed from TURP or adenoma enucleation samples and thus were staged either T1a (< 5% cancer) or T1b, depending on the proportion of the tissue that was cancerous. The majority of PHS patients (65%) had T1 or T2 tumors.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Prostate Cancer Patients in the Swedish and PHS Cohorts

| Characteristic | PHS Cohort(n = 109) |

Swedish Cohort(n = 358) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | |

| Years of diagnosis | 1983-2003 | 1987-1999 | ||

| Gleason score | ||||

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| 6 | 12 | 11 | 106 | 30 |

| 3 + 4 | 34 | 31 | 85 | 24 |

| 4 + 3 | 30 | 28 | 74 | 20 |

| 8 | 18 | 16 | 22 | 6 |

| 9 | 12 | 11 | 56 | 16 |

| 10 | 3 | 3 | 12 | 3 |

| Clinical outcomes | ||||

| Lethal cases | 30 | 28 | 171 | 48 |

| Stage | ||||

| T1a-N0-MX | 110 | 31 | ||

| T1b-N0-MX | 241 | 69 | ||

| T1/T2 | 70 | 65 | ||

| T3 | 28 | 26 | ||

| T4/N1/M1 | 10 | 9 | ||

| Missing | 1 | 7 | ||

| Age at diagnosis, years (mean ± SD) | 67.3 ± 7 | 73.4 ± 7 | ||

Abbreviations: PHS, Physicians' Health Study; SD, standard deviation.

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristics of Patients in the Swedish and PHS Cohorts, Stratified by Gleason Category

| Characteristic | Total No. of Patients | Long-Term Survivors |

Patients With Lethal Cancer |

Age at Diagnosis(mean years ± SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | |||

| Swedish cohort | ||||||

| Gleason ≤ 6 | 109 | 88 | 81 | 21 | 19 | 71.6 ± 7 |

| Gleason ≥ 8 | 89 | 14 | 16 | 75 | 84 | 74.6 ± 7 |

| Gleason 3 + 4 | 85 | 52 | 61 | 33 | 39 | 72.8 ± 7 |

| Gleason 4 + 3 | 74 | 33 | 45 | 41 | 55 | 75.3 ± 7 |

| PHS cohort | ||||||

| Gleason ≤ 6 | 12 | 12 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 64.4 ± 4 |

| Gleason ≥ 8 | 33 | 11 | 33 | 22 | 67 | 70.4 ± 8 |

| Gleason 3 + 4 | 34 | 33 | 97 | 1 | 3 | 66.1 ± 6 |

| Gleason 4 + 3 | 30 | 23 | 77 | 7 | 23 | 66.4 ± 7 |

Abbreviations: PHS, Physicians' Health Study; SD, standard deviation.

To improve contrast of Gleason phenotypes in initial analyses, we compared tumors with Gleason score ≤ 6 to those with Gleason score ≥ 8. In the Swedish cohort, after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, 107 genes remained significant at the family-wise 0.05 level (Appendix Table A1, online only) after 6,100 t tests comparing low Gleason score with high Gleason score; 784 genes had a false discovery rate (FDR) less than 0.05. In the PHS, a smaller data set of two genes were significant at the family-wise 0.05 level (Appendix Table A2, online only); 74 genes had an FDR less than 0.05. The top 10% of genes in the Swedish cohort were enriched in the top 10% of genes in the PHS cohort (P < .001).

Pooling the cohorts, we applied a gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)24,25 to identify pathways commonly enriched among high-grade or low-grade cancers. We identified 15 pathways from the GSEA database that were enriched among the high-grade tumors and three pathways that were enriched among the low-grade tumors with an FDR less than 0.10 (Table 3). The enriched pathways in the high-grade tumors are involved in the cell cycle, PI3K/AKT pathway, pyrimidine metabolism, and one-carbon folate, while pathways in the low-grade tumors were related to propanoate metabolism.

Table 3.

Gene Pathways Enriched in High-Grade (Gleason ≥ 8) or Low-Grade (Gleason ≤ 6) Tumors, Based on Gene Set Enrichment Analysis Using Molecular Signature Databases From the Broad Institute

| Pathways Enriched in High-Grade Tumors | Pathway Description | Pathways Enriched in Low-Grade Tumors |

|---|---|---|

| CELL_CYCLE_KEGG | HSA00640_PROPANOATE_METABOLISM | |

| HSA04110_CELL_CYCLE | PROPANOATE_METABOLISM | |

| G1_TO_S_CELL_CYCLE_REACTOME | HSA00410_BETA_ALANINE_METABOLISM | |

| DNA_REPLICATION_REACTOME | ||

| PTDINSPATHWAY | PI3K phosphorylate inositol rings of phosphoinositide lipids, influencing vesicle trafficking, cell proliferation, and migration | |

| GSK3PATHWAY | Bacterial lipopolysaccharide activates AKT to promote the survival and activation of macrophages and inhibits Gsk3-beta to promote beta-catenin accumulation in the nucleus | |

| ST_GA13_PATHWAY | G-alpha-13 influences the actin cytoskeleton and activates protein kinase D, PI3K, and Pyk2 | |

| PYRIMIDINE_METABOLISM | ||

| HSA00240_PYRIMIDINE_METABOLISM | ||

| ONE_CARBON_POOL_BY_FOLATE | ||

| HSA00670_ONE_CARBON_POOL_BY_FOLATE | ||

| MRNA_PROCESSING_REACTOME | ||

| EPOPATHWAY | Erythropoietin, which activates the MAPK pathway, stimulates erythrocyte production and is an effective treatment for anemia | |

| HSA04330_NOTCH_SIGNALING_PATHWAY | ||

| HSA04120_UBIQUITIN_MEDIATED_PROTEOLYSIS |

NOTE. False discovery rate < 0.1. Lines divide pathways into clusters based on large numbers of overlapping genes.

Abbreviation: PI3K, phosphoinositide 3 kinase.

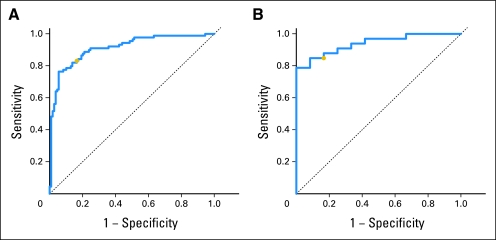

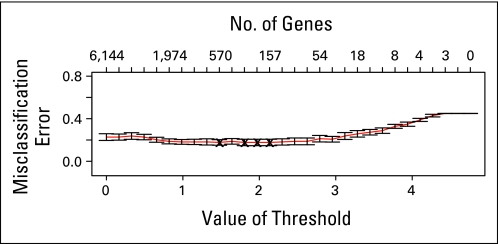

Separating the cohorts again, we built and tested a signature to predict high and low Gleason grades using PAM. We built the model in the Swedish data set (the training set) and estimated the level of misclassification of Gleason pattern using cross validation. The most parsimonious model that minimized misclassification contained 157 genes (Appendix Table A3, online only) and had an average misclassification rate of 17% of the two Gleason classes in the Swedish cohort (Appendix Fig A1, online only). We further examined the predictive ability of the genes in this set by measuring the area under the [concentration-time] curve (AUC) which was 0.91 (95% CI, 0.87 to 0.95; Fig 1A). When our model from PAM was applied to the testing set (PHS data), the average misclassification rate was 16% in the two groups, and the AUC was 0.94 (95% CI, 0.86 to 0.99; Fig 1B). When we built a signature using PAM on the PHS data and applied it to the Swedish cohort, the results for misclassification and AUC were similar (data not shown).

Fig 1.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for the 157-gene signature developed with prediction analysis of microarrays. (A) ROC curve for the model built in the Swedish cohort for Gleason ≤ 6 and Gleason ≥ 8, applied to those same men. (B) ROC curve for the model built in the Swedish cohort applied to men in the Physicians' Health Study with Gleason ≤ 6 and Gleason ≥ 8. In each plot, the gold dot is where misclassification rates are approximately equal in the two groups.

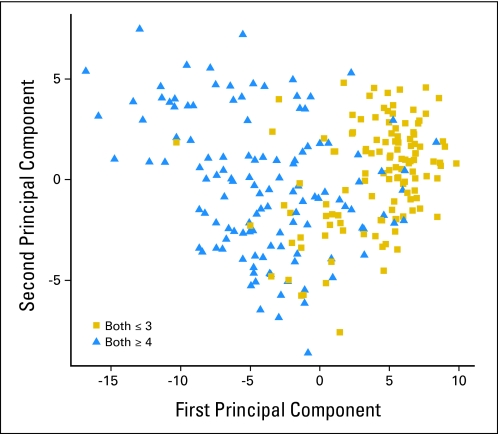

We examined the overall variability in expression of the 157 genes in the signature. Pooling the two cohorts, we calculated the first two principal components of the 157 genes in the model (Fig 2). The tumors with Gleason ≤ 6 patterns seem to have fairly consistent values of the first principal component, suggesting more homogeneity in expression of genes. In contrast, those with Gleason ≥ 8 tumors have a more varied expression pattern. We observed that among individuals with Gleason ≥ 8, as they are further to the right of Figure 2 (more like the Gleason ≤ 6), their risk of lethal prostate cancer significantly decreases (P = .03).

Fig 2.

The first two principal components of the 157-gene model in the Swedish and Physicians' Health Study data sets, comparing men with Gleason ≤ 6 (Both ≤ 3) and men with Gleason ≥ 8 (Both ≥ 4).

We then applied the 157-gene signature to the 159 men in the Swedish cohort and the 64 men in the PHS with Gleason 7 tumors to see whether those with Gleason 4 + 3 would be more likely classified by the signature as Gleason ≥ 8 than those with Gleason 3 + 4. The predictive ability to discriminate 4 + 3 from 3 + 4 cancer was statistically significant but of modest magnitude; the AUC for this model was 0.60 (95% CI, 0.53 to 0.68).

However, the 157-gene signature improved prediction of lethality among the men with Gleason 7, a group with mixed predictive ability. We used logistic regression to predict prostate cancer–specific death among the Swedish men with Gleason 7; we included in the model the Gleason score (4 + 3 v 3 + 4) and the estimated probability of being high grade from the 157-gene signature. We found that the probability of being high grade from the gene signature statistically significantly predicted lethal prostate cancer (odds ratio [OR], 1.46; 95% CI, 1.09 to 1.95 per 33% increase in predicted probability of being high grade); the gene signature provided a significant improvement over the model with Gleason score alone (likelihood ratio test P = .01). In an independent assessment in the PHS cohort, the OR was identical but the association was nonsignificant (OR, 1.44; 95% CI, 0.57 to 3.68), reflecting the smaller sample size. Combining the men with Gleason 7 from the two cohorts, we found that the OR was 1.47 (95% CI, 1.11 to 1.94) for a 33% increase in the model prediction. This model, which included an indicator of Gleason score (4 + 3 v 3 + 4), an indicator of cohort, and the predicted probabilities from our model, was significantly improved over a model with just Gleason score and cohort (likelihood ratio test P = .006). Adding age at diagnosis to the model does not change the predictive ability (OR, 1.48; P = .006).

We compared the frequency of lethal cancers by tertiles of our predicted probability. One third of the men received predicted probabilities between 0 and 0.16, one third between 0.16 and 0.73, and one third between 0.73 and 1. Twenty-nine percent of the men in the lowest tertile died of prostate cancer compared with 36% of the men in the middle tertile and 45% of the men in the upper tertile; thus, the difference in frequency of death between the lowest and highest tertiles was 16%.

DISCUSSION

Gleason grade is one of the strongest clinical predictors of prostate cancer progression. Men with low-grade Gleason ≤ 6 tumors, have a low metastatic potential, even in the absence of therapy28; in contrast, men with high-grade Gleason 8 to 10 tumors have a high likelihood of progression, even with curative therapies. There is mixed discrimination among the men diagnosed with Gleason 7 tumors, who represent a substantial proportion of prostate cancers diagnosed currently in the United States and other western countries. Improving risk prediction among patients with Gleason 7, as well as understanding the mechanisms leading to prostate tumor differentiation, is paramount to understanding this heterogeneous disease.

In this large study with long-term follow-up, we identified sets of genes that differentiate between low and high Gleason grade in a Swedish and a US cohort of men with prostate cancer. Additionally, we used a GSEA to identify the key pathways that go awry in the de-differentiation process in prostate cancer. Finally, we developed a Gleason signature that was significantly predictive of lethal prostate cancer among the men with Gleason 7, independent of 3 + 4 or 4 + 3 status. While this result warrants further study, it provides additional proof of principle for the utility of expression profiling in understanding the clinical heterogeneity of prostate cancer. This signature may have direct clinical application for men diagnosed with Gleason 7 tumors, the largest category of patients, and the one that poses the greatest challenges for treatment decision.

An additional finding was that, when examining the first two principal components of the genes in our 157-gene model, there was more homogeneity in patterns of expression among patients with Gleason ≤ 6 than among those with Gleason ≥ 8. This is consistent with the findings of True et al12 that Gleason pattern 3 alterations are fairly similar, while pattern 4 and 5 tumors are more diverse, even occasionally having features of pattern 3. We consider this analogous to the first line of Tolstoy's Anna Karenina: “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”29 Minor loss of differentiation may occur in the same pathways and genes in most individuals, but greater loss of normal structure can occur in many different ways. We noted that as Gleason ≥ 8 tumors looked more like Gleason ≤ 6 tumors, the risk of lethal prostate cancer significantly decreased.

While we could reliably distinguish Gleason ≤ 6 from Gleason ≥ 8 in both our training and our test data sets, the signature did not discriminate well between Gleason 3 + 4 and 4 + 3. As we and others have shown, outcomes in the clinically heterogeneous category of Gleason 7 tumors can be further refined by determining the predominant Gleason score.8,30–32 The inability to identify a gene signature that distinguishes between Gleason 3 + 4 and 4 + 3 may be due to the way the tissues were collected—the Gleason grade of the exact cores used for mRNA extraction may not perfectly match the overall grade assigned to the patient. Therefore, the core from a Gleason score 7 could be Gleason grade 3, Gleason grade 4, or some combination of the two patterns.

In a previous examination of these datasets, we noted that the overall expression profiles for the Swedish and PHS samples differed substantially, most likely because of the types of specimens used (TURP for the Swedish cohort; 88% RP for the PHS cohort). Our data suggest that the genes that predict Gleason score are robust regardless of the technique used for tissue collection, because we developed a signature in TURP samples and validated it in mostly RP specimens.

This study is larger than previous studies that address this question, includes centrally reviewed and standardized Gleason score measurements, and is able to examine the association of the developed signature with lethal prostate cancer. We examined only a subset of all known genes, so there could be many other genes that predict Gleason score. However, the 6,100 genes were selected specifically for possible involvement in prostate cancer, so they may capture a large proportion of the variation.

Our results provide many biologic hypotheses for genes and pathways that may underlie the differentiation of prostate cancer tissue. One pathway we identified through GSEA that involved the cell cycle was recently reported to be the module most strongly associated with Gleason in lymphoblastoid cell lines from patients with prostate cancer.33 Since Gleason score is a strong predictor of outcome, the pathways identified here may be important in disease progression as well.

The expression signature identified may enhance our understanding of the de-differentiation process of prostate tumors and may have clinical applications for men with Gleason 7 tumors, improving the prediction of lethal cancer and thereby guiding therapy decisions. The use of these prediction tools, or perhaps further refined versions, is likely to improve outcomes while reducing the overtreatment of indolent disease.

Appendix

Table A1.

Ranking of Top Significant Genes From Individual t Tests in the Swedish Cohort

| Rank | Gene | P | Fold Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MYBPC1 | 6.26E-14 | 0.94 |

| 2 | EYA1 | 9.73E-14 | 0.927 |

| 3 | BCAS1 | 3.09E-13 | 0.905 |

| 4 | BIRC5 | 4.13E-10 | 1.105 |

| 5 | ALOX15B | 4.74E-10 | 0.89 |

| 6 | MT1G | 5.96E-10 | 0.929 |

| 7 | PAGE4 | 7.30E-10 | 0.917 |

| 8 | MPPED2 | 1.50E-09 | 0.934 |

| 9 | EHHADH | 1.59E-09 | 0.915 |

| 10 | GARS | 2.28E-09 | 1.023 |

| 11 | SMPDL3A | 3.90E-09 | 0.962 |

| 12 | BGN | 5.69E-09 | 1.046 |

| 13 | MT1F | 5.74E-09 | 0.957 |

| 14 | PRKCB1 | 5.89E-09 | 0.948 |

| 15 | CRIP2 | 1.16E-08 | 1.079 |

| 16 | MCM4 | 1.20E-08 | 1.063 |

| 17 | PTTG1 | 1.24E-08 | 1.078 |

| 18 | LMNB1 | 1.30E-08 | 1.066 |

| 19 | ENAH | 1.48E-08 | 1.022 |

| 20 | ARG2 | 1.69E-08 | 0.96 |

| 21 | NOTCH3 | 2.54E-08 | 1.064 |

| 22 | CDC42BPA | 3.00E-08 | 1.037 |

| 23 | UBE2C | 3.42E-08 | 1.073 |

| 24 | JAG1 | 4.02E-08 | 1.065 |

| 25 | SERPINA3 | 4.67E-08 | 0.94 |

| 26 | MRPS12 | 5.19E-08 | 1.067 |

| 27 | CDKN3 | 5.39E-08 | 1.075 |

| 28 | DRAP1 | 8.03E-08 | 1.023 |

| 29 | FMO5 | 8.57E-08 | 0.936 |

| 30 | TFF3 | 9.87E-08 | 0.965 |

| 31 | ABAT | 1.18E-07 | 0.963 |

| 32 | SATB1 | 1.22E-07 | 0.955 |

| 33 | KCNMA1 | 1.25E-07 | 0.974 |

| 34 | COL4A1 | 1.31E-07 | 1.038 |

| 35 | GOLPH2 | 1.40E-07 | 0.987 |

| 36 | MT2A | 1.46E-07 | 0.986 |

| 37 | HNRPAB | 1.46E-07 | 1.015 |

| 38 | MT1X | 1.49E-07 | 0.969 |

| 39 | DLGAP1 | 1.60E-07 | 0.968 |

| 40 | CHRNA2 | 1.66E-07 | 0.943 |

| 41 | PSMD4 | 1.66E-07 | 1.02 |

| 42 | DLG7 | 1.92E-07 | 1.063 |

| 43 | INHBA | 2.10E-07 | 1.079 |

| 44 | SMC4 | 2.53E-07 | 1.026 |

| 45 | ITPR2 | 2.63E-07 | 0.959 |

| 46 | STIP1 | 2.72E-07 | 1.024 |

| 47 | F5 | 2.86E-07 | 1.046 |

| 48 | RPE65 | 3.11E-07 | 0.964 |

| 49 | FAM50A | 3.57E-07 | 1.027 |

| 50 | RGS4 | 4.60E-07 | 1.071 |

| 51 | CYP27A1 | 4.61E-07 | 0.947 |

| 52 | NEK2 | 4.63E-07 | 1.073 |

| 53 | RRM2 | 4.97E-07 | 1.068 |

| 54 | MAT2A | 5.37E-07 | 1.022 |

| 55 | ATP8A2 | 5.44E-07 | 1.095 |

| 56 | GMDS | 6.67E-07 | 0.972 |

| 57 | TOP2A | 6.77E-07 | 1.073 |

| 58 | BUB1B | 7.85E-07 | 1.074 |

| 59 | VEGF | 8.40E-07 | 1.056 |

| 60 | DDEF2 | 8.73E-07 | 1.037 |

| 61 | CPT1A | 9.74E-07 | 1.029 |

| 62 | CENPF | 1.16E-06 | 1.068 |

| 63 | FKBP1B | 1.17E-06 | 0.944 |

| 64 | GNG4 | 1.24E-06 | 0.946 |

| 65 | SEMA3F | 1.24E-06 | 0.967 |

| 66 | SH3BGRL | 1.28E-06 | 0.974 |

| 67 | GPR116 | 1.28E-06 | 1.06 |

| 68 | ASPN | 1.40E-06 | 1.068 |

| 69 | CXCL13 | 1.43E-06 | 0.914 |

| 70 | CYC1 | 1.43E-06 | 1.02 |

| 71 | ANXA3 | 1.51E-06 | 0.975 |

| 72 | KLF5 | 1.60E-06 | 0.961 |

| 73 | DBT | 1.65E-06 | 0.989 |

| 74 | F2R | 1.86E-06 | 1.051 |

| 75 | SCUBE2 | 2.02E-06 | 1.077 |

| 76 | SPARCL1 | 2.68E-06 | 0.972 |

| 77 | SEMA3C | 2.86E-06 | 0.97 |

| 78 | CSE1L | 3.22E-06 | 1.023 |

| 79 | NTRK3 | 3.29E-06 | 0.94 |

| 80 | FXYD1 | 3.34E-06 | 0.957 |

| 81 | SLC15A2 | 3.40E-06 | 0.952 |

| 82 | MYLK | 3.64E-06 | 0.965 |

| 83 | CYB5A | 4.03E-06 | 0.961 |

| 84 | UQCRC1 | 4.71E-06 | 1.026 |

| 85 | TYMS | 4.88E-06 | 1.054 |

| 86 | PTPRN2 | 4.93E-06 | 0.962 |

| 87 | MT1A | 5.48E-06 | 0.929 |

| 88 | ADH5 | 5.70E-06 | 0.972 |

| 89 | MAP3K5 | 5.71E-06 | 1.037 |

| 90 | GSTA4 | 5.85E-06 | 0.969 |

| 91 | CAND1 | 5.91E-06 | 1.026 |

| 92 | CD38 | 6.31E-06 | 0.924 |

| 93 | SERPING1 | 6.36E-06 | 0.979 |

| 94 | SPAG5 | 6.42E-06 | 1.073 |

| 95 | PRC1 | 6.43E-06 | 1.036 |

| 96 | TLE1 | 6.43E-06 | 1.033 |

| 97 | BMP6 | 6.71E-06 | 1.057 |

| 98 | TRIP13 | 6.72E-06 | 1.055 |

| 99 | IL1R1 | 7.07E-06 | 0.968 |

| 100 | NUSAP1 | 7.08E-06 | 1.055 |

| 101 | RAB27A | 7.36E-06 | 0.971 |

| 102 | TK1 | 7.37E-06 | 1.051 |

| 103 | DPP4 | 7.40E-06 | 0.938 |

| 104 | PTK7 | 7.55E-06 | 1.045 |

| 105 | CLU | 7.88E-06 | 0.978 |

| 106 | COPS5 | 8.04E-06 | 1.041 |

| 107 | MGST1 | 8.13E-06 | 0.961 |

NOTE. Bonferroni P < .05.

Table A2.

Ranking of Top Significant Genes From Individual t Tests in the PHS

| Rank | Gene | P | Fold Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | POLR2E | 8.16E-07 | 1.033 |

| 2 | GARS | 6.92E-06 | 1.042 |

NOTE. Bonferroni P < .05.

Abbreviation: PHS, Physicians' Health Study.

Table A3.

Listing of 157 Genes in Our Model, in Order of Entrance Into the Model (ie, in order of size of standardized shrunken centroid difference)

| Genes |

|---|

| BCAS1 |

| ALOX15B |

| EYA1 |

| PAGE4 |

| BIRC5 |

| MYBPC1 |

| MT1G |

| EHHADH |

| MPPED2 |

| PTTG1 |

| CRIP2 |

| CXCL13 |

| UBE2C |

| SERPINA3 |

| ATP8A2 |

| INHBA |

| LMNB1 |

| CDKN3 |

| MCM4 |

| FMO5 |

| NOTCH3 |

| NEK2 |

| PRKCB1 |

| MT1F |

| CHRNA2 |

| SCUBE2 |

| TOP2A |

| RRM2 |

| JAG1 |

| CD38 |

| MRPS12 |

| BUB1B |

| RGS4 |

| BGN |

| ANPEP |

| GNG4 |

| ASPN |

| CYP27A1 |

| FKBP1B |

| KCNN2 |

| SPAG5 |

| GPR116 |

| MT1A |

| VEGF |

| ARG2 |

| DPP4 |

| SFTPA2 |

| CENPF |

| DLG7 |

| SMPDL3A |

| SERPINE1 |

| PGM5 |

| SC65 |

| NTRK3 |

| CYP4F12 |

| SATB1 |

| ERG |

| NELL2 |

| HSD17B6 |

| KHDRBS3 |

| TFF3 |

| PENK |

| F2R |

| ABAT |

| SLC15A2 |

| PROK1 |

| COL4A1 |

| TYMS |

| ITPR2 |

| CDC42BPA |

| FXYD1 |

| NUSAP1 |

| CACNA1D |

| BMP6 |

| DHFR |

| XRCC2 |

| PTN |

| TK1 |

| KLF5 |

| RARRES1 |

| ESM1 |

| TRIP13 |

| PAH |

| PTK7 |

| CYB5A |

| PTPRN2 |

| MGST1 |

| IGFBP6 |

| MYLK |

| PLA2G7 |

| GRIA3 |

| MT1X |

| SLC4A4 |

| DLGAP1 |

| C2 |

| FOXM1 |

| DDEF2 |

| CSPG2 |

| F5 |

| CUL7 |

| SEMA3F |

| COPS5 |

| SCGB1D2 |

| CCNB1 |

| GREB1 |

| PHC2 |

| GMNN |

| CES1 |

| TBXAS1 |

| HERC3 |

| RGS16 |

| FLRT2 |

| E2F3 |

| KIAA0040 |

| TGFB2 |

| ESRRG |

| ARMCX2 |

| PLA2G10 |

| RNASE4 |

| HIST1H1T |

| ENTPD1 |

| ELK4 |

| SHMT2 |

| NAT1 |

| EVPL |

| LIPH |

| MAP3K5 |

| LCN2 |

| RPE65 |

| TPST1 |

| CRISP3 |

| LAMC1 |

| ASNS |

| MEOX2 |

| SEMA3C |

| FST |

| FGF7 |

| HRAS |

| PLCG1 |

| AOX1 |

| ANG |

| UPP1 |

| MYBL2 |

| TLE1 |

| IL1R1 |

| OCLN |

| MMP11 |

| SPARCL1 |

| AZGP1 |

| GSTA4 |

| RAB27A |

| GMDS |

| EPHB6 |

| NME3 |

| KIAA0907 |

| CPT1A |

| HOXB7 |

Fig A1.

Misclassification error rates from prediction analysis of microarrays estimated by cross validation in the Swedish cohort for models with differing numbers of genes. These models try to distinguish between men with Gleason ≤ 6 and those with Gleason ≥ 8. The red line is the proportion of samples misclassified, with error bars given in black.

Footnotes

Supported by Grants No. 5P50CA090381-08 from the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Prostate Specialized Programs of Research Excellence program and No. 5R01CA141298 from the National Cancer Institute. The Physicians' Health Study was supported by Grants No. CA-34944, CA-40360, and CA-097193 from the National Cancer Institute and HL-26490 and HL-34595 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The Swedish Watchful Waiting cohort was supported by the Swedish Cancer Foundation and The Örebro County Council Research Foundation. Supported by National Research Service Award T32 CA009001-32 (K.L.P.), Grant No. GM-074897 (J.A.S.), and the Prostate Cancer Foundation (L.A.M.).

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: None Consultant or Advisory Role: Todd R. Golub, Foundation Medicine (C) Stock Ownership: Todd R. Golub, Foundation Medicine Honoraria: None Research Funding: None Expert Testimony: None Other Remuneration: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Kathryn L. Penney, Jennifer A. Sinnott, Katja Fall, Yudi Pawitan, Jennifer R. Stark, Stephen Finn, Richard Flavin, Matthew L. Freedman, Sunita Setlur, Swen-Olof Andersson, Neil Martin, Philip W. Kantoff, Jan-Erik Johansson, Hans-Olov Adami, Mark A. Rubin, Massimo Loda, Todd R. Golub, Ove Andrén, Meir J. Stampfer, Lorelei A. Mucci

Financial support: Philip W. Kantoff, Jan-Erik Johansson, Todd R. Golub

Collection and assembly of data: Jennifer A. Sinnott, Katja Fall, Yudi Pawitan, Yujin Hoshida, Jennifer R. Stark, Michelangelo Fiorentino, Sven Perner, Stephen Finn, Stefano Calza, Richard Flavin, Sunita Setlur, Howard D. Sesso, Swen-Olof Andersson, Jan-Erik Johansson, Mark A. Rubin, Massimo Loda, Todd R. Golub, Ove Andrén, Meir J. Stampfer, Lorelei A. Mucci

Data analysis and interpretation: Kathryn L. Penney, Jennifer A. Sinnott, Yudi Pawitan, Peter Kraft, Michelangelo Fiorentino, Stefano Calza, Matthew L. Freedman, Howard D. Sesso, Neil Martin, Massimo Loda, Todd R. Golub, Meir J. Stampfer, Lorelei A. Mucci

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Stark JR, Mucci L, Rothman KJ, et al. Screening for prostate cancer remains controversial. BMJ. 2009;339:b3601. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, et al. Screening and prostate-cancer mortality in a randomized European study. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1320–1328. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Cancer Society . American Cancer Society Cancer Facts and Figures 2010. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeFrances CJ, Lucas CA, Buie VC, et al. 2006 National Hospital Discharge Survey. Natl Health Stat Report. 2008;5:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sboner A, Demichelis F, Calza S, et al. Molecular sampling of prostate cancer: A dilemma for predicting disease progression. BMC Med Genomics. 2010;3:8. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-3-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheville JC, Karnes RJ, Therneau TM, et al. Gene panel model predictive of outcome in men at high risk of systemic progression and death from prostate cancer after radical retropubic prostatectomy. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3930–3936. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.6752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gleason DF. Classification of prostatic carcinomas. Cancer Chemother Rep. 1966;50:125–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stark JR, Perner S, Stampfer MJ, et al. Gleason score and lethal prostate cancer: Does 3 + 4 = 4 + 3? J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3459–3464. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.4669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Best CJ, Leiva IM, Chuaqui RF, et al. Molecular differentiation of high- and moderate-grade human prostate cancer by cDNA microarray analysis. Diagn Mol Pathol. 2003;12:63–70. doi: 10.1097/00019606-200306000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh D, Febbo PG, Ross K, et al. Gene expression correlates of clinical prostate cancer behavior. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:203–209. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lapointe J, Li C, Higgins JP, et al. Gene expression profiling identifies clinically relevant subtypes of prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:811–816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0304146101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.True L, Coleman I, Hawley S, et al. A molecular correlate to the Gleason grading system for prostate adenocarcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:10991–10996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603678103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bibikova M, Chudin E, Arsanjani A, et al. Expression signatures that correlated with Gleason score and relapse in prostate cancer. Genomics. 2007;89:666–672. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mendes A, Scott RJ, Moscato P. Microarrays: Identifying molecular portraits for prostate tumors with different Gleason patterns. Methods Mol Med. 2008;141:131–151. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-148-6_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomlins SA, Mehra R, Rhodes DR, et al. Integrative molecular concept modeling of prostate cancer progression. Nat Genet. 2007;39:41–51. doi: 10.1038/ng1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andrén O, Fall K, Franzén L, et al. How well does the Gleason score predict prostate cancer death? A 20-year followup of a population based cohort in Sweden. J Urol. 2006;175:1337–1340. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00734-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aus G, Nordenskjöld K, Robinson D, et al. Prognostic factors and survival in node-positive (N1) prostate cancer: A prospective study based on data from a Swedish population-based cohort. Eur Urol. 2003;43:627–631. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(03)00156-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johansson JE, Andrén O, Andersson SO, et al. Natural history of early, localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 2004;291:2713–2719. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.22.2713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Final report on the aspirin component of the ongoing Physicians' Health Study: Steering Committee of the Physicians' Health Study Research Group N Engl J Med. 1989;321:129–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198907203210301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hennekens CH, Buring JE, Manson JE, et al. Lack of effect of long-term supplementation with beta carotene on the incidence of malignant neoplasms and cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1145–1149. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605023341801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Setlur SR, Mertz KD, Hoshida Y, et al. Estrogen-dependent signaling in a molecularly distinct subclass of aggressive prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:815–825. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bibikova M, Talantov D, Chudin E, et al. Quantitative gene expression profiling in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues using universal bead arrays. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1799–1807. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63435-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoshida Y, Villanueva A, Kobayashi M, et al. Gene expression in fixed tissues and outcome in hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1995–2004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mootha VK, Lindgren CM, Eriksson KF, et al. PGC-1alpha-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat Genet. 2003;34:267–273. doi: 10.1038/ng1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Broad Institute. Gene set enrichment analysis. http://www.broad.mit.edu/gsea/

- 27.Tibshirani R, Hastie T, Narasimhan B, et al. Diagnosis of multiple cancer types by shrunken centroids of gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6567–6572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082099299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Albertsen PC, Hanley JA, Fine J. 20-year outcomes following conservative management of clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 2005;293:2095–2101. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.17.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tolstoy L. Anna Karenina. New York, NY: Viking Penguin; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chan TY, Partin AW, Walsh PC, et al. Prognostic significance of Gleason score 3+4 versus Gleason score 4+3 tumor at radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2000;56:823–827. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00753-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Makarov DV, Sanderson H, Partin AW, et al. Gleason score 7 prostate cancer on needle biopsy: Is the prognostic difference in Gleason scores 4 + 3 and 3 + 4 independent of the number of involved cores? J Urol. 2002;167:2440–2442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rasiah KK, Stricker PD, Haynes AM, et al. Prognostic significance of Gleason pattern in patients with Gleason score 7 prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;98:2560–2565. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang L, Tang H, Thayanithy V, et al. Gene networks and microRNAs implicated in aggressive prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:9490–9497. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]