Abstract

Purpose

Research has documented cognitive deficits both before and after high-dose treatment followed by allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT), with partial recovery by 1 year. This study prospectively examined the trajectory and extent of long-term cognitive dysfunction, with a focus on 1 to 5 years after treatment.

Patients and Methods

Allogeneic HCT recipients completed standardized neuropsychological tests including information processing speed (Trail Making A and Digit Symbol Substitution Test), verbal memory (Hopkins Verbal Learning Test–Revised), executive function (Controlled Oral Word Association Test and Trail Making B), and motor dexterity and speed (Grooved Pegboard). Survivors (n = 92) were retested after 80 days and 1 and 5 years after transplantation. Case-matched controls (n = 66) received testing at the 5-year time point. A Global Deficit Score (GDS) summarized overall impairment. Response profiles were analyzed using linear mixed effects models.

Results

Survivors recovered significant cognitive function from post-transplantation (80 days) to 5 years in all tests (P < .0001) except verbal recall (P > .06). Between 1 and 5 years, verbal fluency improved (P = .0002), as did executive function (P < .01), but motor dexterity did not (P > .15), remaining below controls (P < .0001) and more than 0.5 standard deviation below population norms. In GDS, 41.5% of survivors and 19.7% of controls had mild or greater deficits (NcNemar test = 7.04, P = .007).

Conclusion

Although neurocognitive function improved from 1 to 5 years after HCT, deficits remained for more than 40% of survivors. Risk factors, mechanisms and rehabilitation strategies need to be identified for these residual deficits.

INTRODUCTION

Neurocognitive deficits have important functional impacts on adults who survive cancer treatment and wish to return to work and other activities that require memory, information processing speed, multitasking, and coordination. A growing body of evidence across cancer diagnoses shows that cognitive deficits exist for some patients long after cancer treatment has been completed.1–5 Most cancer-related studies of cognitive impairment have been conducted in patients with breast cancer, with meta-analyses estimating rates of impairment ranging from 16% to 50% in survivors tested from 6 months to 10 years after treatment.1,3,6 Recent consensus conferences on the cognitive effects of chemotherapy recommend that researchers conduct longitudinal studies, including pre- and post-treatment neuropsychological assessments, and also include appropriate comparison groups such as noncancer controls.1,2

Myeloablative conditioning followed by hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is among the more neurotoxic cancer treatments, with acute deficits documented in memory, attention, and information-processing speed.7–11 Research that has assessed patients 6 months or longer post-HCT indicates some recovery of cognitive function after acute deficits.7–9,11–15 However, to our knowledge, no prospective studies have followed HCT patients beyond 2 years after transplantation.

The purpose of this investigation was to determine the trajectory of neurocognitive changes after HCT in a cohort tested from before treatment to 5 years, with an emphasis on the 1- to 5-year time frame. Neurocognitive changes in this cohort of patients over the first year after transplantation have been previously reported.7 Results documented residual deficits in verbal fluency, verbal memory and psychomotor coordination. The current research added the 5-year follow-up to the trajectory previously described and compared the 5-year outcomes of these HCT survivors to those of case-matched controls. On the basis of previous research, we hypothesized the following: 1 Further improvement in remaining areas of deficit (verbal fluency, verbal memory, and motor dexterity and speed) would be observed between 1 and 5 years; and 2 survivors and controls would not differ across the tests administered at 5 years.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Participants

Inclusion criteria, determined on arrival at the transplant center, were impending receipt of a first allogeneic, myeloablative transplant for a malignancy or myelodysplasia, age ≥ 22 years, and English speaking and writing ability. Exclusion criteria included major psychiatric disorder not in remission, active CNS disease, and medical condition impairing function, including active treatment with a CNS toxic agent (eg, opioids or intrathecal methotrexate).

At the 5-year assessment, relapse-free survivors were asked to nominate a case-matched control. Specifically, they identified a biologic sibling of the same sex and within 5 years of the patient's age who had not received a transplant and was not in active treatment for cancer. If no such sibling existed, survivors nominated a friend of the same sex, known since before transplantation, within 5 years of the survivor's age, and of the same ethnicity, race, and education (< 4-year college degree v at least a college degree), who had not received cancer treatment. Because survivors and controls resided throughout the United States, we selected for testing those who lived within a 6-hour drive of an airport and where at least four survivors or controls could be tested during the same trip. Priority was given to testing survivors versus nominated controls. When nominated controls were not accessible, community volunteers were recruited through posters at community sites in Seattle. Controls were matched to survivors on the same factors as friends.

Procedure

The study was prospective and longitudinal in design, with neuropsychological assessments at four time points: 2 to 14 days before the start of HCT treatment, 80 ± 10 days after transplantation, 1 year ± 1 month after transplantation, and 5 years ± 3 months after transplantation.

All procedures were approved by the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center's institutional review board. Patients provided written consent to participate before beginning their transplantation. Controls provided written consent at the 5-year assessment. The psychometrist at the laboratory of the senior author (S.D.) trained three study psychologists in standardized administration of the tests. Testing for the first three time points took place in the ambulatory clinic at the transplant center. At 5 years, one of the psychologists (J.B.E.) traveled to participants' homes for testing. Home procedures were similar to clinic procedures in that only the psychologist and survivor or control were in the room, seated at a table on chairs across from each other. If necessary, the psychologist arranged for testing at a local site that met these same criteria (eg, an office).

Measures

Demographic information was assessed by patient report. Cancer diagnosis, stage of disease, relapse, and survival status were abstracted from research medical records.

Neuropsychological Tests

Estimated IQ.

Pretransplant intelligence quotient (IQ) was estimated with the Information subscale of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-III).16 At 5 years, two subscales of the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI), Vocabulary and Matrix Reasoning, were administered to both survivors and controls.17 These scores were not included in longitudinal analyses or the Global Deficit Scores.

Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWA).

The COWA is an executive control measure that assesses word finding, verbal initiation, and fluency.18–20 Subjects were asked to say all the words they could think of beginning with a given letter within 60 seconds. Raw scores reflected the count of all acceptable words produced for three different letters. Three alternative versions were counterbalanced. All 5-year testing used the letters F, A, and S.

Digit Symbol Substitution Test (Digit Symbol).16

The Digit Symbol is a measure of information-processing speed and requires sustained attention, visual–motor integration, and learning. The timed test requires the subject to examine a series of symbols and to substitute a symbol for each number as indicated by a key. The raw score was the number of blanks filled in correctly in 90 seconds. Alternative versions were counterbalanced.

Hopkins Verbal Learning Test–Revised (HVLT-R).21

The HVLT-R is a verbal list-learning task that assesses episodic memory, learning, and retention of learned material. The task requires recall of 12 words after presentation by an examiner over three trials. The raw score was the sum of words recalled over the three trials. A second score, delayed recall, was the number of words recalled 20 to 25 minutes after completion of the initial task. Alternative versions were counterbalanced.

Grooved Pegboard (Pegboard).22

The Pegboard measures motor speed and dexterity. Subjects insert pegs into a board containing slotted holes angled in different directions. The raw score was time to completion in seconds.

Trail Making Test (Trails A and B).23

Trails A requires visual scanning, graphomotor speed, and attention, whereas Trails B adds components of executive function, including set shifting, inhibitory control, and flexibility. Trails A requires participants to connect numbers, randomly distributed across a page, in sequence. Trails B requires participants to connect randomly distributed numbers and letters, alternating sequentially between the two. In both tests, the raw score was the number of seconds required to correctly complete the task.

Statistical Analysis

End points for the longitudinal analyses were T scores for each task based on population norms for raw scores adjusted for age, sex, and education. T scores have a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10 and permit comparison across tests and to normative performance.

The primary analyses examined longitudinal response profiles of neuropsychological functioning in 5-year relapse-free survivors. Longitudinal trajectories were fitted using linear mixed effects models with heterogeneous Toeplitz (banded) correlation structure to account for differing variance at each time point, within-patient correlations, and data missing at random. The primary reasons for missing data included that survivors were not at the transplant center at assessment times, or at 5 years they lived in a location where in-person testing was not feasible. Thus we are reasonably confident that the 5-year nonmortality missing data were “missing completely at random.”24

Five-year survivors and controls were compared by demographic characteristics and neuropsychological function using paired t tests and χ2 tests. To gauge the clinical relevance of deficits, we described incidence and persistence of at least mild cognitive impairment, defined as a T score lower than 40,2 indicating function more than 1 standard deviation below norms. At 5 years, we calculated a Global Deficit Score, indicative of overall impairment severity.25 Each test was given a score from 0 (T score ≥ 40 = no impairment) to 5 (T score ≤ 19 = severe impairment), in increments of 0.5 standard deviation below 40 (35 to 39 = 1, 30 to 34 = 2, and so on). Impairment severity scores were then averaged across the eight tests. An average score of ≥ 0.5 has been proposed as the optimal cutoff for detecting impairment in cancer survivors, indicative of at least mild impairment on half of the tests.25 Linear mixed effects models were estimated using SAS/STAT software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Other analyses were conducted using SPSS version 16.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL) and R version 2.11.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Cohorts

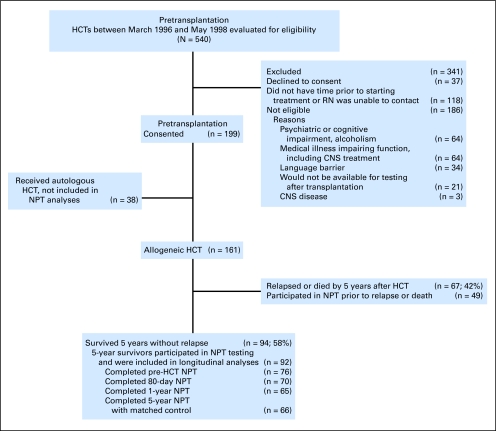

Of the 161 participants, 67 (42%) did not survive for 5 years after HCT without morphologic relapse (Fig 1), and two survivors had no neuropsychological testing (NPT). For the 92 patients in the analytic sample (5-year relapse-free survivors [RFS] with at least one NPT), the completion rate across time was 75%. Sixty-six survivors had matched controls at 5 years. For controls, 24 (36%) were siblings, 27 (41%) were friends, and 15 (23%) were community volunteers. No differences in age, education, or neuropsychological test scores were detected between the three control subgroups (P > .05).

Fig 1.

Flow diagram of patients in longitudinal study. HCT, hematopoietic cell transplantation; NPT, neuropsychological testing; RN, registered nurse.

Characteristics of the 92 5-year survivors who participated in NPT were compared with those of matched controls (Table 1) and those of the 49 NPT participants who were not 5-year RFS (Tables 1 and 2). Survivors did not differ from other HCT recipients in age, sex, or race (P > .3), but had higher education levels than non-RFS (P = .02), differences in conditioning regimens (P = .009), and marginally better prognosis (risk variable) at time of transplantation (P = .06). Six survivors (9.1%) were taking chronic graft-versus-host disease medications at 5 years.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics for Participants at Pretransplantation and After 5 Years

| Characteristic | 5-Year Survivors Participating in NPT at Any Time Point (n = 92) |

5-Year Non-RFS Participating in NPT at Any Time Point (n = 49) |

P | 5-Year Survivors Completing NPT at 5 Years(n = 66) |

Matched Controls at 5 Years(n = 66) |

P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |||

| Age, years | ||||||||||

| Mean | 40.7 | 41.3 | .72 | 46.2 | 46.6 | .83 | ||||

| SD | 9.2 | 9.4 | 9.1 | 9.7 | ||||||

| Range | 22-61 | 25-59 | 31-68 | 27-65 | ||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Male | 43 | 47 | 25 | 51 | .63 | 31 | 47 | 31 | 47 | Matched |

| Female | 49 | 53 | 24 | 49 | 35 | 53 | 35 | 53 | ||

| Race/ethnicity | .31 | Matched | ||||||||

| White/non-Hispanic | 87 | 95 | 47 | 96 | 63 | 95 | 63 | 95 | ||

| Hispanic | 5 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 5 | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Education | .02 | .45 | ||||||||

| High school or less | 24 | 26 | 23 | 47 | 14 | 21 | 14 | 21 | ||

| Some college or trade degree | 18 | 20 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 15 | 15 | 23 | ||

| 4-year college | 24 | 26 | 16 | 33 | 22 | 33 | 20 | 30 | ||

| Degree | 19 | 21 | 2 | 4 | 14 | 21 | 14 | 21 | ||

| Master's or doctoral degree | 7 | 7 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 9 | 3 | 5 | ||

| Estimated IQ | ||||||||||

| WAIS, Information | .07 | — | — | — | ||||||

| Mean | 49.0 | 46.2 | ||||||||

| SD | 8.4 | 8.6 | ||||||||

| WASI, Vocabulary | — | — | .93 | |||||||

| Mean | 55.6 | 55.5 | ||||||||

| SD | 8.5 | 6.1 | ||||||||

| WASI, Matrix Reasoning | — | — | .11 | |||||||

| Mean | 55.9 | 58.3 | ||||||||

| SD | 8.9 | 7.7 | ||||||||

Abbreviations: NPT, neuropsychological testing; RFS, relapse-free survivors; SD, standard deviation; WAIS, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (scores reported are age, sex, and education adjusted T scores with population mean of 50 and SD of 10); WASI, Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (scores reported are age, sex, and education adjusted T scores with population mean of 50 and SD of 10).

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristics for Participants Pretransplantation and at 5 Years

| Characteristic | 5-Year Survivors Participating in NPT at Any Time Point(n = 92) |

5-Year Non-RFS Participating in NPT at Any Time Point(n = 49) |

P | 5-Year Survivors Completing NPT at 5 Years(n = 66) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Diagnosis | .43 | ||||||

| Chronic myeloid leukemia | 48 | 52 | 21 | 43 | 35 | 53 | |

| Acute leukemia | 18 | 20 | 11 | 22 | 14 | 21 | |

| Lymphoma | 9 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 6 | 9 | |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 12 | 13 | 5 | 10 | 7 | 11 | |

| Other | 5 | 5 | 7 | 15 | 4 | 6 | |

| Treatment regimens | .009 | ||||||

| Cyclophosphamide and 12 or 13.2 Gy of total-body irradiation | 48 | 52 | 28 | 57 | 34 | 52 | |

| Cyclophosphamide and busulfan | 37 | 40 | 9 | 18 | 26 | 39 | |

| Other chemotherapy and total-body irradiation | 6 | 7 | 10 | 20 | 5 | 7.5 | |

| Other chemotherapy | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1.5 | |

| Risk* | .06 | ||||||

| Low | 46 | 50 | 21 | 43 | 32 | 49 | |

| Intermediate | 33 | 36 | 13 | 26 | 24 | 36 | |

| High | 13 | 14 | 15 | 31 | 10 | 15 | |

Abbreviations: NPT, neuropsychological testing; RFS, relapse-free survivors.

Risk is based on diagnosis and remission/relapse status on admission for hematopoietic cell transplantation: low = myelodysplasia, chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase; intermediate = acute leukemia or lymphoma in remission; high = acute leukemia or lymphoma in relapse.

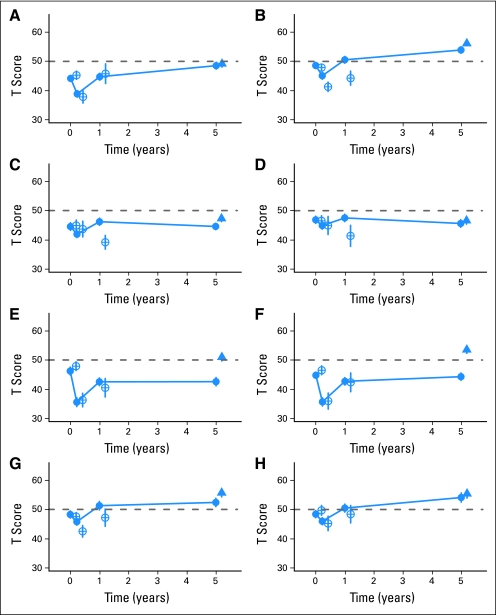

Trajectories of Neurocognitive Function Over Time

Linear mixed effects models were fitted for the eight NPT outcomes. Fitted average values for pre-HCT and at 80 days, 1 year, and 5 years after HCT are shown in Table 3, with 95% CIs for the mean. The fitted models are shown graphically in Figure 2, with solid lines connecting estimates from different time points of the same model for 5-year RFS. Additionally, fitted values and SEs are displayed at each time point for the observed data of non-RFS patients. Average values for the matched controls are also shown in Table 3 and Figure 2, with comparisons to the 5-year values for survivors. The 80-day assessment was the nadir for all measures. However, the average T score before transplantation was lower descriptively than the general population average of 50 for each of the eight measures. The pre-HCT and 80-day average scores of survivors were close to those of non-RFS for most measures, whereas 1-year participants who were non-RFS by 5 years (n = 13) had lower scores than survivors for the Digit Symbol (P = .049), HVLT-R (P = .021), and HVLT-R delayed (P = .058).

Table 3.

Average Fitted Values for Neuropsychological Tests at Four Time Points for 5-Year Relapse-Free Survivors of HCT (N = 92)

| Time Point | COWA |

P | Digit Symbol |

P | HVLT-R |

P | HVLT-R Delay |

P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Fitted Value | 95% CI | Average Fitted Value | 95% CI | Average Fitted Value | 95% CI | Average Fitted Value | 95% CI | |||||

| Pre-HCT | 44.1 | 42.1 to 46.2 | < .0001 | 48.6 | 46.4 to 50.7 | < .0001 | 44.5 | 41.9 to 47.1 | .984 | 46.8 | 44.4 to 49.3 | .409 |

| 80 days | 38.8 | 36.6 to 41.0 | < .0001 | 45.1 | 42.7 to 47.4 | < .0001 | 41.9 | 39.6 to 44.1 | .062 | 44.9 | 42.4 to 47.3 | .604 |

| 1 year | 44.7 | 42.4 to 47.1 | .0002 | 50.6 | 48.3 to 52.8 | .0003 | 46.2 | 43.7 to 48.6 | .238 | 47.5 | 45.0 to 50.0 | .156 |

| 5 years | 48.5 | 46.2 to 50.8 | — | 53.9 | 51.7 to 56.1 | — | 44.5 | 42.4 to 46.7 | — | 45.6 | 43.0 to 48.1 | — |

| Matched controls | 49.2 | 47.0 to 51.4 | .907 | 56.2 | 54.2 to 58.1 | .248 | 47.3 | 45.2 to 49.4 | .060 | 46.6 | 44.2 to 49.0 | .513 |

| Pegboard Dominant Hand |

P | Pegboard Nondominant Hand |

P | Trails A |

P | Trails B |

P | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Fitted Value | 95% CI | Average Fitted Value | 95% CI | Average Fitted Value | 95% CI | Average Fitted Value | 95% CI | |||||

| Pre-HCT | 46.2 | 43.6 to 48.8 | .017 | 44.7 | 42.6 to 46.9 | .683 | 48.3 | 45.8 to 50.7 | .005 | 48.4 | 46.0 to 50.8 | .0003 |

| 80 days | 35.5 | 32.6 to 38.5 | < .0001 | 35.6 | 32.8 to 38.3 | < .0001 | 45.8 | 43.4 to 48.2 | < .0001 | 46.0 | 43.6 to 48.3 | < .0001 |

| 1 year | 42.5 | 39.9 to 45.1 | .973 | 42.7 | 40.1 to 45.2 | .192 | 51.3 | 48.4 to 54.2 | .425 | 50.5 | 47.8 to 53.2 | .008 |

| 5 years | 42.6 | 39.8 to 45.4 | — | 44.3 | 41.8 to 46.7 | — | 52.4 | 49.6 to 55.2 | — | 54.1 | 51.0 to 57.2 | — |

| Matched controls | 51.0 | 48.4 to 53.5 | < .0001 | 53.5 | 51.1 to 56.0 | < .0001 | 55.7 | 53.0 to 58.5 | .076 | 55.4 | 52.5 to 58.3 | .929 |

NOTE. P values are for Wald tests comparing average 5-year fitted scores with average fitted scores at other time points, using linear contrasts within a linear mixed effects model. The last row indicates P values for paired ttests in comparison with controls (n = 66).

Abbreviations: COWA, Controlled Oral Word Association Test; HCT, hematopoietic cell transplantation; HVLT-R, Hopkins Verbal Learning Test–Revised.

Fig 2.

Time trajectories from pretransplantation to 5 years, by years after transplantation, for survivors participating at 5 years (filled circles, n = 92), controls (filled triangles, n = 66), and non–relapse-free survivors after pretransplantation (open circle, n = 44), after 80 days (open circle, n = 20), and after 1 year (open circle, n = 13). Dashed line indicates general population norm for each test (T score, 50). (A) Controlled Oral Word Association Test; (B) Digit Symbol Substitution Test; (C) Hopkins Verbal Learning Test–Revised (HVLT); (D) HVLT delayed; (E) Grooved Pegboard, dominant hand; (F) Grooved Pegboard, nondominant hand; (G) Trail Making Test A; (H) Trail Making Test B. See Table 3 for statistical comparisons between time points and 5-year survivors/controls.

As reported earlier,7 by 1 year after HCT, NPT function had recovered to pretransplantation levels, with the exception of the Pegboard. Importantly, survivors demonstrated further improvement in several measures between 1 and 5 years (COWA, P = .0002; Digit Symbol, P = .001; Trails B, P = .008). For several measures the 5-year average score was significantly higher than pre-HCT (COWA, P < .001; Digit Symbol, P < .001; Trails A, P = .005; Trails B, P = .001). Transplant recipients showed persistent deficits in motor speed and dexterity on the Pegboard (P = .017 for dominant hand; P = .683 for nondominant hand). On the HVLT, 5-year survivors did not improve beyond their pre-HCT functioning.

Comparison of Survivors and Controls

Most differences between 5-year survivors and matched controls were not striking. The exception was for motor speed and dexterity (Pegboard average difference 8.2 points for dominant, 9.1 points for nondominant, P < .001 for both). There were trends for controls' T scores to be higher for verbal memory (HVLT-R difference 2.7 points, P = .060) and for attention and visual scanning speed (Trails A difference 3.9 points, P = .076), but not for other measures (Table 3).

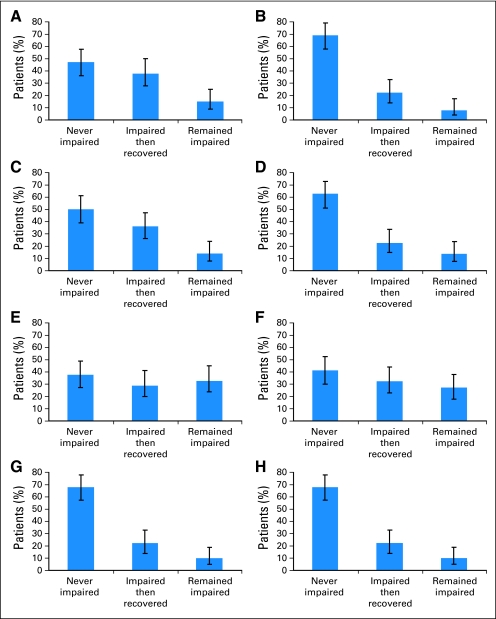

Rates of Impairment

The incidence and persistence of impairment are summarized in Figure 3. For each measure, patients were categorized into one of three groups based on earlier (pre-HCT and 80-day) and later (1-year and 5-year) assessments. The “never impaired” group did not show impairment at any of the measured time points. (One each of the earlier and later assessments could be missing.) More than two thirds of the patients were never impaired on the Digit Symbol or Trails A and B, whereas fewer than half of those tested were consistently normal on the Pegboard. The “recovery” groups were those impaired at pre-HCT or 80 days but not at 1 or 5 years. These groups were 22% to 38% of patients across the eight measures. The “impaired” groups were those impaired at pre-HCT or 80 days and remaining impaired at 1 or 5 years. These groups were 9% to 33% of patients across the eight measures. Of note, three or fewer survivors declined in function as indicated by being not impaired at pre-HCT and/or 80 days, but impaired at 1 year and/or 5 years. For the Global Deficit Score (GDS), 41.5% of survivors and 19.7% of controls scored ≥ 0.5 (McNemar test = 7.04, P = .007), indicative of mild or greater impairment in neuropsychological function overall. For the 5-year survivors, 38% had impairment in the mild range (GDS of 0.50 to 1.99), with 3% in the moderate range (2.00 to 4.99) and none in the severe range.

Fig 3.

Incidence and persistence patterns of impairment for each neuropsychological test (n = 92), with missing ranging from n = 21 to 24 depending on the specific test, with 95% CI boundaries. For each measure, each patient was categorized into one of three groups based on earlier (pre–hematopoietic cell transplantation [HCT] and 80-day) and later (1-year and 5-year) assessments. The “never impaired” group did not show impairment at either pre-HCT or 80 days, and showed normal functioning (T score ≥ 40) at 1 year, 5 years, or both. The “impaired then recovered” group included those impaired at pre-HCT or 80 days and not impaired at 1 or 5 years. The “remained impaired” group included those impaired at pre-HCT or 80 days who remained impaired at the latest assessment (ie, 1 or 5 years or both after HCT). (A) Controlled Oral Word Association Test; (B) Digit Symbol Substitution Test; (C) Hopkins Verbal Learning Test–Revised (HVLT); (D) HVLT delayed; (E) Grooved Pegboard, dominant hand; (F) Grooved Pegboard, nondominant hand; (G) Trail Making Test A; (H) Trail Making Test B.

DISCUSSION

This prospective study of neurocognitive function over 5 years after HCT found that, between 1 and 5 years, further neurocognitive recovery continued to occur in the areas of information-processing speed and executive function, even though neurocognitive function for most survivors had returned to pretransplantation levels by 1 year. However, contrary to expectations, neither motor dexterity nor verbal learning and retention improved between 1 and 5 years. Deficits were most notable in motor speed and dexterity relative to both population norms and matched controls. Mostly mild, neurocognitive dysfunction remained at 5 years for twice as many long-term survivors (41.5%) versus controls (19.7%), as indicated by the GDS.

The finding that several measures improved by 5 years to be above pre-HCT levels, including tests of executive function (COWA, Trails B) confirms that testing before HCT is not a true baseline, and return to baseline in test results does not represent a return to premorbid functioning. Premorbid functioning at or above average is also indicated by the IQ tests of vocabulary and matrix reasoning, where both survivors' and controls' mean scores were more than 0.5 standard deviation above population norms. Deficits after diagnosis and before treatment have been noted by other investigators.10,26 Potential mechanisms for pre- and post-HCT neurocognitive deficits are hypothesized to include cytokine and immune dysregulation, damage to DNA through cytotoxic agents, original disease or oxidative stress, inefficient DNA repair mechanisms, hormonal changes, or stress.2,27

We are not aware of other neurocognitive studies that have followed survivors for 5 years after cancer treatment. These 5-year findings are consistent with studies of shorter term HCT deficits recognized by previous research, with persistent difficulties focused on motor coordination and speed in more than a third of survivors, even in largely autologous HCT cohorts.8,9,28 Memory impairment levels are variable across studies and are not clearly associated with conditioning regimens for HCT.7–10,28 In a meta-analysis of NPT effects across types of cancer diagnoses and treatments, largest effect sizes were found for executive function and verbal memory, when compared with norms.3 In contrast, our research indicates that executive function largely recovers, given sufficient time, for most HCT survivors, although consistent with other research, memory is less resilient.

Cognitive changes owing to chemotherapy are often subtle. Functioning may be reduced and detectable to the individual, but remain in the normal range.27 The consequence of this mild decline may contribute to frustration in survivors who recognize their change in cognitive performance, but whose deficits are not identifiable when only post-HCT NPT is available. Unlike results observed with pediatric survivors of HCT, this study found no evidence of later decline in cognitive function in relapse-free survivors.29

This study has several strengths and limitations. The prospective cohort design and case-matched controls at 5 years are notable strengths, recommended as methodologies for neurocognitive investigations of cancer survivors.1 This study also used a majority of the recommended tests for standardizing methodology.2 With regard to limitations, attrition and practice effects may mask some deficits, particularly relative to controls,25,30 although these effects are proving to be less than might be expected and are most notable for motor speed.9,26 The inability to test controls in the same longitudinal pattern as patients is another limitation that does not allow us to directly examine practice effects.30,31 The time lag from 1 to 5 years is likely to decrease the influence of practice. Attrition effects between 1 and 5 years are unknown. However, in demographic and medical characteristics, the RFS participants are indistinguishable from the RFS nonparticipants at 5 years. Nonetheless, a relatively small number of survivors could be tested at 5 years, as a result of both mortality and the challenges of traveling for face-to-face testing. Results are not generalizable to HCT recipients who received autologous transplants or reduced-intensity conditioning regimens.

The major clinical implication of this research is to assure HCT recipients and their health care providers that further progress will occur in their information-processing capacity between 1 and 5 years after treatment. However, it is equally important to validate for long-term survivors that not all HCT recipients fully recover neurocognitive function by 5 years. These results provide further indication of the need for cognitive rehabilitation strategies after 1 year for those with residual deficits. Unfortunately, several studies attempting neuropsychological rehabilitation immediately after HCT found no difference in deficits when comparing a training group led by an occupational therapist or computer-based training under direction of a therapist versus controls who did not receive training.32 Research with non-HCT cancer survivors has demonstrated variable efficacy in small studies to improve neurocognitive function using medications such as methylphenidate or modafinil.1,33–35 However, studies that teach adults compensatory mechanisms for managing cognitive deficits have shown promise36 and warrant further testing.

Footnotes

Supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (Grants No. CA63030, CA78990, and CA112631).

Presented at the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation/Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research Tandem meeting, February 14, 2008, San Diego, CA.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Karen L. Syrjala, Sari Roth-Roemer, Sureyya Dikmen

Financial support: Karen L. Syrjala

Provision of study materials or patients: Karen L. Syrjala

Collection and assembly of data: Karen L. Syrjala, Shelby L. Langer, Sari Roth-Roemer, JoAnn Broeckel Elrod

Data analysis and interpretation: Karen L. Syrjala, Samantha B. Artherholt, Brenda F. Kurland, Sureyya Dikmen

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Tannock IF, Ahles TA, Ganz PA, et al. Cognitive impairment associated with chemotherapy for cancer: Report of a workshop. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2233–2239. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vardy J, Wefel JS, Ahles T, et al. Cancer and cancer-therapy related cognitive dysfunction: An international perspective from the Venice cognitive workshop. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:623–629. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson-Hanley C, Sherman ML, Riggs R, et al. Neuropsychological effects of treatments for adults with cancer: A meta-analysis and review of the literature. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2003;9:967–982. doi: 10.1017/S1355617703970019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poppelreuter M, Weis J, Kulz AK, et al. Cognitive dysfunction and subjective complaints of cancer patients. a cross-sectional study in a cancer rehabilitation centre. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butt Z, Wagner LI, Beaumont JL, et al. Use of a single-item screening tool to detect clinically significant fatigue, pain, distress, and anorexia in ambulatory cancer practice. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stewart A, Bielajew C, Collins B, et al. A meta-analysis of the neuropsychological effects of adjuvant chemotherapy treatment in women treated for breast cancer. Clin Neuropsychol. 2006;20:76–89. doi: 10.1080/138540491005875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Syrjala KL, Dikmen S, Langer SL, et al. Neuropsychologic changes from before transplantation to 1 year in patients receiving myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant. Blood. 2004;104:3386–3392. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harder H, Van Gool AR, Duivenvoorden HJ, et al. Case-referent comparison of cognitive functions in patients receiving haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for haematological malignancies: Two-year follow-up results. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:2052–2059. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobs SR, Small BJ, Booth-Jones M, et al. Changes in cognitive functioning in the year after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer. 2007;110:1560–1567. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schulz-Kindermann F, Mehnert A, Scherwath A, et al. Cognitive function in the acute course of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for hematological malignancies. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;39:789–799. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wenz F, Steinvorth S, Lohr F, et al. Prospective evaluation of delayed central nervous system [CNS] toxicity of hyperfractionated total body irradiation [TBI] Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;48:1497–1501. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)00764-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sostak P, Padovan CS, Yousry TA, et al. Prospective evaluation of neurological complications after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Neurology. 2003;60:842–848. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000046522.38465.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harder H, Cornelissen JJ, Van Gool AR, et al. Cognitive functioning and quality of life in long-term adult survivors of bone marrow transplantation. Cancer. 2002;95:183–192. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peper M, Steinvorth S, Schraube P, et al. Neurobehavioral toxicity of total body irradiation: A follow-up in long-term survivors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;46:303–311. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00442-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang G, Meadows ME, Orav EJ, et al. Mental status changes after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer. 2009;115:4625–4635. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weschler D. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1997. WAIS-III Administration and Scoring Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wechsler D. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment; 1999. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spreen O, Strauss E. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1991. A Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests: Administration, Norms, and Commentary. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lacy MA, Gore PA, Jr, Pliskin NH, et al. Verbal fluency task equivalence. Clin Neuropsychol. 1996;10:305–308. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gladsjo JA, Schuman CC, Evans JD, et al. Norms for letter and category fluency: Demographic corrections for age, education, and ethnicity. Assessment. 1999;6:147–178. doi: 10.1177/107319119900600204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benedict RHB, Schretlen D, Groninger L, et al. Hopkins verbal learning test revised: Normative data and analysis of inter-form and test-retest reliability. Clin Neuropsychol. 1998;12:43–55. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reitan RM, Davison LA. Washington, DC: Hemisphere Publishing; 1974. Clinical Neuropsychology: Current Status and Applications. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reitan RM, Wolfson D. Tucson, AZ: Neuropsychology Press; 1985. The Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery: Theory and Clinical Interpretation. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Little RJA, Rubin DB. New York, NY: John Wiley; 1987. Statistical Analysis With Missing Data. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vardy J, Rourke S, Tannock IF. Evaluation of cognitive function associated with chemotherapy: A review of published studies and recommendations for future research. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2455–2463. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Friedman MA, Fernandez M, Wefel JS, et al. Course of cognitive decline in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A within-subjects design. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2009;24:689–698. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acp060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahles TA, Saykin AJ. Candidate mechanisms for chemotherapy-induced cognitive changes. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:192–201. doi: 10.1038/nrc2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Booth-Jones M, Jacobsen PB, Ransom S, et al. Characteristics and correlates of cognitive functioning following bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;36:695–702. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shah AJ, Epport K, Azen C, et al. Progressive declines in neurocognitive function among survivors of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for pediatric hematologic malignancies. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2008;30:411–418. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e318168e750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dikmen SS, Heaton RK, Grant I, et al. Test-retest reliability and practice effects of expanded Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 1999;5:346–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benedict RH, Zgaljardic DJ. Practice effects during repeated administrations of memory tests with and without alternate forms. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1998;20:339–352. doi: 10.1076/jcen.20.3.339.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poppelreuter M, Weis J, Mumm A, et al. Rehabilitation of therapy-related cognitive deficits in patients after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;41:79–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lundorff LE, Jonsson BH, Sjogren P. Modafinil for attentional and psychomotor dysfunction in advanced cancer: A double-blind, randomised, cross-over trial. Palliat Med. 2009;23:731–738. doi: 10.1177/0269216309106872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mar Fan HG, Clemons M, Xu W, et al. A randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial of the effects of d-methylphenidate on fatigue and cognitive dysfunction in women undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:577–583. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0341-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meyers CA, Weitzner MA, Valentine AD, et al. Methylphenidate therapy improves cognition, mood, and function of brain tumor patients. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:2522–2527. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.7.2522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferguson RJ, Ahles TA, Saykin AJ, et al. Cognitive-behavioral management of chemotherapy-related cognitive change. Psycho-Oncology. 2007;16:772–777. doi: 10.1002/pon.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]