Abstract

Purpose: The deterministic Acuros XB (AXB) algorithm was recently implemented in the Eclipse treatment planning system. The goal of this study was to compare AXB performance to Monte Carlo (MC) and two standard clinical convolution methods: the anisotropic analytical algorithm (AAA) and the collapsed-cone convolution (CCC) method.

Methods: Homogeneous water and multilayer slab virtual phantoms were used for this study. The multilayer slab phantom had three different materials, representing soft tissue, bone, and lung. Depth dose and lateral dose profiles from AXB v10 in Eclipse were compared to AAA v10 in Eclipse, CCC in Pinnacle3, and EGSnrc MC simulations for 6 and 18 MV photon beams with open fields for both phantoms. In order to further reveal the dosimetric differences between AXB and AAA or CCC, three-dimensional (3D) gamma index analyses were conducted in slab regions and subregions defined by AAPM Task Group 53.

Results: The AXB calculations were found to be closer to MC than both AAA and CCC for all the investigated plans, especially in bone and lung regions. The average differences of depth dose profiles between MC and AXB, AAA, or CCC was within 1.1, 4.4, and 2.2%, respectively, for all fields and energies. More specifically, those differences in bone region were up to 1.1, 6.4, and 1.6%; in lung region were up to 0.9, 11.6, and 4.5% for AXB, AAA, and CCC, respectively. AXB was also found to have better dose predictions than AAA and CCC at the tissue interfaces where backscatter occurs. 3D gamma index analyses (percent of dose voxels passing a 2%∕2 mm criterion) showed that the dose differences between AAA and AXB are significant (under 60% passed) in the bone region for all field sizes of 6 MV and in the lung region for most of field sizes of both energies. The difference between AXB and CCC was generally small (over 90% passed) except in the lung region for 18 MV 10 × 10 cm2 fields (over 26% passed) and in the bone region for 5 × 5 and 10 × 10 cm2 fields (over 64% passed). With the criterion relaxed to 5%∕2 mm, the pass rates were over 90% for both AAA and CCC relative to AXB for all energies and fields, with the exception of AAA 18 MV 2.5 × 2.5 cm2 field, which still did not pass.

Conclusions: In heterogeneous media, AXB dose prediction ability appears to be comparable to MC and superior to current clinical convolution methods. The dose differences between AXB and AAA or CCC are mainly in the bone, lung, and interface regions. The spatial distributions of these differences depend on the field sizes and energies.

Keywords: deterministic dose calculation, Acuros XB, Monte Carlo, anisotropic analytical algorithm, collapsed-cone convolution

INTRODUCTION

Dose calculation algorithms for radiation therapy have improved profoundly over the last few decades.1 Most notably, the development of model-based convolution methods has significantly improved the accuracy of dose calculations for heterogeneous materials when compared to the conventional correction-based methods.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 The development of computer hardware and variance reduction techniques for stochastic Monte Carlo (MC) methods has largely reduced the computation time, making MC feasible in clinical treatment planning systems (TPSs).8, 9, 10 However, the complexity of modern radiotherapy has increased with the development of image-guided and intensity-modulated delivery techniques.11, 12, 13, 14 These patient-specific techniques place higher demands on the dose calculation accuracy for planning optimization. Although the MC method can be considered as the gold standard in accuracy given sufficient particle histories, calculation times may not be short enough for clinical use with these advanced techniques.10

Recently, dose calculations using a deterministic grid-based Boltzmann equation solver (GBBS or the discrete ordinates method) were investigated for accuracy and potential for clinical applications.15, 16, 17, 18 The GBBS directly discretizes the linear Boltzmann transport equation (LBTE), which governs the macroscopic behavior of particle interactions with matter, in space, and in angle and energy domains. The GBBS then iteratively solve the radiation transport problem within specified volumes to compute radiation doses. Historically, GBBS algorithms have been developed and used in various neutral- and charged-particle shielding calculations,19, 20, 21 but they seldom have been used in external photon beam dose calculations. In 2006, Gifford et al. investigated the potential of Attila, a general-purpose GBBS developed by Los Alamos National Laboratories (Los Alamos, NM) and licensed to Transpire, Inc. (Gig Harbor, WA), for low-dose-rate Cesium-137 brachytherapy sources loaded inside a shielded gynecological applicator and for 1.5 × 1.5 cm2 18 MV external photon beam dose calculations.15 They demonstrated that the dose results, in particular in the high dose gradient region, from Attila were comparable to those from MC packages MCNPX and EGS4. Based on these results, Transpire Inc. wrote a new version of GBBS (Acuros™) to improve the efficiency and accuracy for radiotherapy applications. Vassiliev et al. have validated the dose calculations from this prototype version of Acuros™ with EGSnrc MC simulations.17, 18 Recently, the Acuros algorithm was licensed by Varian Medical Systems (Palo Alto, CA) and integrated in the Eclipse TPS as the Acuros® XB (AXB) advanced dose calculation algorithm.

Although the AXB algorithm has many similarities with the prototype version of Acuros reported by Vassiliev et al.,17, 18 some modifications and optimizations were implemented within the Eclipse TPS, such as beam modeling and material assignment. Therefore, the absorbed dose distribution predicted by AXB still needs to be verified prior to clinical use. Furthermore, clinicians and researchers who wish to adopt AXB in the future may need to compare AXB with their current dose calculation algorithms to account for differences between them. Thus, the aims of this study were to compare the heterogeneous dose distributions of AXB to MC and two standard clinical convolution methods: anisotropic analytical algorithm (AAA) in Eclipse and the collapsed-cone convolution (CCC) in Pinnacle.3 As a fundamental study, we focus our comparison on a simple geometric slab phantom recommended by Rogers and Mohan.22 Since this phantom is identical to the previous study on validation of the prototype Acuros,18 the same MC methods were used as benchmark to evaluate the performance of AXB, AAA, and CCC. Comparisons of MC with AXB and convolution-based methods included depth dose and lateral dose profiles. To further examine the dosimetric differences between AXB and convolution methods, three-dimensional (3D) gamma indices using AXB as the reference for AAA and CCC were generated and analyzed in more detailed subregions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

AXB advanced dose calculation

The detailed mathematical algorithms for the GBBS have been described in previous publications.15, 18 The AXB used in this study is a preclinical release of version 10.0.24, which was implemented on the Eclipse TPS (Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA). A description of the AXB algorithm and its implementation in Eclipse is given below.

Beam model and configuration

The photon beam source model in AXB is the same model used by the existing AAA in Eclipse. A MC simulation of the treatment unit head was used to develop a fundamental parameterized model of radiation output for a clinical linear accelerator. There are four components in the photon beam source model: primary photons, scattered photons, contaminant electron source, and the wedge scatter source.23 By modifying the parameters of these components, the customized phase-space that defines the fluence and energy spectrum specific to each clinical beam can be constructed. The parameters for a specific clinical beam can be created and modified using the Beam Configuration module in Eclipse.

In this study, we commissioned a Varian Clinac 2100 accelerator. The open-field profiles and relative output data were obtained from Varian golden beam data and imported into Eclipse. By using these data, we needed to make only minimal manual configurations in the beam configuration module to match and assign add-ons.24 The results (parameters) produced from this one-time configuration were validated against the measured data for open fields in a water phantom as a part of our clinical commissioning process.

Deterministic GBBS for radiation transport

AXB calculates the 3D patient dose deterministically using three components: the primary photon source model, the scattered photon fluence, and the scattered electron fluence.23 For the primary photon source, the beam source is modeled and ray tracing is performed to calculate the uncollided particle distributions for every computed tomography (CT) voxel inside the patient boundary. For the scattered photon and electron fluences, the AXB algorithm solves the LBTE to produce scattered particle distribution functions for every voxel in the patient boundary. Once the total energy-dependent particle flux was obtained, the dose value was calculated by a flux-to-dose response function.

Unlike convolution methods, which generally model heterogeneous materials by applying a density-related correction to a dose kernel in water, AXB explicitly models the physical interaction of radiation in the material and solves the radiation-transport problem numerically. More specifically, AXB uses multigroup energy, discrete-ordinate angular discretization, and linear discontinuous finite-element spatial differencing methods to respectively discretize the energy, angle, and space variables of the LBTE and iteratively solves the differential form of the transport equation in a discrete, multidimensional space. For multigroup energy, both the energy dependence of the collision components and the Boltzmann scattering are discretized. The AXB cross-section library includes 25 photon energy groups and 49 electron energy groups.23 These cross-sections were the same as those used in EGSnrc MC simulation. For the discrete-ordinate angular discretization, the algorithm requires the collision components to be applied to a fixed number of directions. These discrete directions are chosen from an angular quadrature set that is also used in computing the angular integrals for the scattering source. Chebyshev–Legendre quadrature sets are used,25 and the quadrature order ranges from N = 4 (32 discrete angles) to N = 16 (512 discrete angles). AXB uses an adaptive angular quadrature order that varies by both particle type and energy. Higher energy particles have longer mean free paths, and thus for each particle type, the angular quadrature order is increased as a function of the particle’s energy. For the linear discontinuous finite-element spatial differencing, the computational volume domain is subdivided into variable-sized Cartesian elements, in which material properties are assumed to be constant for each computational element. This approach is a third-order accurate for integral quantities and provides a rigorously defined solution at every point in the computational domain. The computational grid in AXB is spatially variable; the local element size is adapted to achieve a higher spatial resolution inside the beam, with reduced resolution in lower dose and lower gradient regions outside the beam’s penumbra.

AXB employs a spatial transport cutoff for electron energies below 500 keV and for photon energies below 1 keV. When a particle’s energy drops below the cutoff value, it is assumed to have deposited all its energy in the corresponding dose grid voxel.

Material assignment in AXB

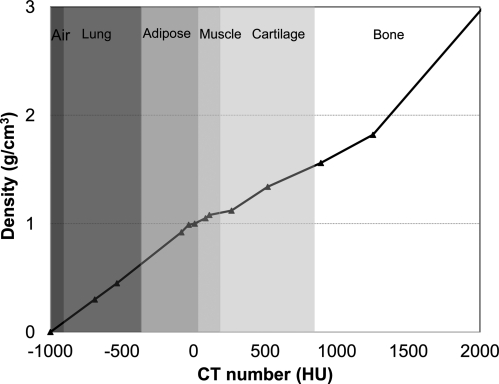

To perform a dose calculation, AXB requires the chemical composition of each material in its computational grid. Eclipse provides AXB with a mass density and material type for each voxel in the image grid. The mass density and material is assigned automatically through a CT number calibration curve or can be manually assigned for a given structure. Figure 1 shows the calibration curve for CT number to mass density conversion from one specific CT scanner used in study. For the material density from 0 to 3.0 g∕cm3, Eclipse defined six biological material types in certain ranges: air, lung tissue, adipose tissue, muscle, cartilage, and bone. The default ranges are also shown in Fig. 1. It should be noted that each CT scanner may have a different calibration curve, and the ranges for material assignment could be slightly adjusted by users.

Figure 1.

Graph of CT number and material assignment versus density that was used in Eclipse TPS for AXB algorithm.

There is a maximum limit of 3.0 g∕cm3 for mass density converted from the Hounsfield unit (HU) value in the CT image. This value is assumed to be the highest density of bone, and any area of an image converted to a density higher than that value requires the user to identify the correct material. As long as some voxels have densities greater than 3.0 g∕cm3, AXB calculations are prevented until a material is assigned via a user-defined structure. This prevents incorrect assignment to a high-density material such as a hip prosthesis.

AXB dose calculation options

The calculation grid size in the x–y (axial) plane for AXB can be defined at any value between 1 and 3 mm and the default value is 2.5 mm. The choice of the grid size is based on the dimensions of the planning geometry. Smaller grid sizes are normally used for smaller planning target volumes. When using smaller grid sizes, the size of the dose matrices becomes larger and the total computation time becomes longer. Within each image plane, the resolution of the dose calculation corresponds to the defined grid size. In the axis perpendicular to the image slices (the z axis), AXB automatically sets the grid resolution to the integer multiple or fraction of the slice spacing closest to the user defined grid size.

Three types of dose results can be obtained from AXB, depending on the selection of heterogeneity correction and dose report mode: dose-to-medium in medium, D(m,m) (AXB default), dose-to-water in medium, D(w,m), and dose-to-water in water, D(w,w) . The first two modes are available when heterogeneity correction is turned on. The difference between these two is only in the postprocessing step, in which the energy-dependent fluence calculated by AXB’s transport is multiplied by different flux-to-dose response functions to obtain the local absorbed dose value. For dose-to-medium, the material for each voxel in the patient image is assigned according to that voxel’s CT number and AXB uses a medium-based response function to obtainD(m,m); similarly, the D(w,m) used a water-based response function. The third option is for heterogeneity correction turned off; all voxels within the patient boundary are set as water. Thus, the results report D(w,w). The default dose report mode for AXB, D(m,m), was used in this study to compare with MC and the convolution methods.

MC simulation

The MC simulation used in this study was similar to the previous study by Vassiliev et al.18 Radiation transport and dose tallying were performed with the DOSXYZnrc program developed by the National Research Council of Canada.26, 27 DOSXYZnrc is based on the EGSnrc general-purpose MC code and allows the radiation transport and dose deposition to be calculated in Cartesian coordinates. The photon beam was modeled in DOSXYZnrc from a point source with realistic 6 and 18 MV energy spectrums that correspond to those of the Varian Clinac 2100.28, 29 It should be noted that this simplified accelerator head model is different from those modeled in the Eclipse and Pinnacle3 TPSs. The effects from electron contamination, flatting-filter, and head scatter were not included in the MC simulation. However, this exclusion would only affect parts of the buildup regions, as described in previous study.18 In this MC simulation, the incident number of photons was selected to reduce the statistical uncertainty to less than 1%, and the electron transport cutoff kinetic energy was set to 189 keV in all the calculations. The MC dose also reports D(m,m). The conversion of MC D(m,m) to D(w,m) was performed following stopping power method by Siebers et al.30

Convolution methods

Two widely used convolution dose calculation algorithms were compared with AXB in this study: AAA 10.0.24 in the Eclipse TPS and CCC in the Pinnacle3 9.0 TPS [Philips Philips Medical Systems (Cleveland), Inc., Fitchburg, WI]. The commissioning of the Varian Clinac 2100 for AAA was similar to that for AXB, which also used the same Varian golden beam data. The model we used in Pinnacle3 was based on a previously commissioned machine using measured beam data from a Varian Clinac 2100 for clinical work at our institution, in which the measured profiles matched well with those from the golden beam data. However, the smallest field size in the existing model was only down to 4 × 4 cm2. In order to allow the calculation of absolute dose for small field sizes in Pinnacle3, we added the measured output factors down to 1 × 1 cm2 and recommissioned this machine. All the plans and dose profiles calculated with DOSXYZnrc and AXB were recalculated using AAA and CCC. The same CT number-density conversion table in Fig. 1 was used for CCC calculations. The CT number-electronic density conversion table for AAA was obtained from the same CT scanner.

AAA dose report mode is generally considered as D(w,m),4, 24, 31 though this is not clearly stated in the Eclipse manual. CCC reports D(m,m) as default in Pinnacle.3, 4, 32 Since both AAA and CCC dose reporting defaults are used clinically, these were compared with the AXB reported D(m,m) without further conversions.

Phantoms and plans

Because this was a fundamental study, we focused on dose validation and comparisons with simple geometrical phantoms. The open-field beam characteristics of all four algorithms in this study (MC, AXB, AAA, and CCC) were initially verified in a homogeneous water phantom. Then, dose calculations for the heterogeneous materials were evaluated using a layered slab phantom.

Homogeneous water phantom

A digital (virtual) water phantom with a volume of 30 × 30 × 30 cm3 and voxel size of 0.1 × 0.1 × 0.1 cm3 was generated with MATLAB R2008b (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA). Then it was converted to the DICOM-CT format and imported into Eclipse and Pinnacle3. For MC calculations, the phantom was imported into DOSXYZnrc using the CTCREATE program.27 Since our TPSs were all commissioned to match the golden beam data, all the profiles were compared with the measured profiles from golden beam data to validate their beam characteristics. The open-field photon beams of two energies (6 and 18 MV) were studied at several field sizes from 3 × 3 to 20 × 20 cm2. The percentage depth dose (PDD) and lateral dose profiles at multiple depths at dmax (1.5 cm for 6 MV and 3.5 cm for 18 MV), 10 cm, and 20 cm were examined. A source-to-surface distance of 100 cm was used for all the calculations. The calculation grid size for all algorithms for this phantom was set to 0.2 × 0.2 × 0.2 cm3.

Layered slab phantom

To evaluate the heterogeneity-based calculations of AXB, an identical layered slab phantom from the previous studies was used.15, 18 This phantom was originally described by Rogers and Mohan22 for benchmarking the heterogeneous dose calculation in MC simulation. The overall dimensions of the phantom were 30 × 30 × 30 cm3. The digital phantom was composed of four layers of 30 × 30 cm2 square slabs with different thicknesses and densities: 3 cm of soft tissue (1.0 g∕cm3), 2 cm of bone (1.85 g∕cm3), 7 cm of lung tissue (0.26 g∕cm3), and another 18 cm of soft tissue (1.0 g∕cm3). The density inside each slab was set constant by specifying a CT number corresponding to the HU-to-density plot shown in Fig. 1. The assignment of a constant density for each material ensured that there were no systematic errors due to material assignment among the algorithms evaluated. Figure 2 depicts the digital phantom created in Eclipse with a beam setup depicting the 10 × 10 cm2 open field as an example.

Figure 2.

Geometric diagram of the layered slab phantom (30 × 30 × 30 cm3) showing the path of a 10 × 10 cm2 open-field beam.

AXB and the convolution algorithms were benchmarked against MC simulation. To be consistent with the previous study, the depth dose profiles along the central axis of the heterogeneous phantom were calculated for the 6 and 18 MV energies with field sizes of 2.5 × 2.5, 5 × 5, and 10 × 10 cm2. Lateral dose profiles were also obtained at the same depths including dmax, 10 cm, and 20 cm.

One of the challenges in heterogeneous dose calculations occurs near the interfaces between two tissues with highly varying densities (such as bone and lung) where the backscatter contribution to locally absorbed dose is important. In order to show the doses near interfaces in more detail, the MC calculation grid sizes were set differently near the bone interface regions: the grid size was set to 0.2 × 0.2 × 0.2 cm3 for most of the volume but 0.1 × 0.1 × 0.2 cm3 near both soft tissue–bone and bone–lung interfaces to more faithfully capture any backscatter effects. The calculation grid size of AXB, AAA, and CCC cannot be changed locally. Hence, to allow a point-to-point comparison with MC, we calculated the AXB, AAA, and CCC dose distributions twice, once with a grid size of 0.2 × 0.2 × 0.2 cm3 for the entire phantom for general comparison and again with a grid size of 0.1 × 0.1 × 0.1 cm3 for a smaller region around the soft tissue–bone and bone–lung interfaces.

Data comparison and 3D gamma analysis

To compare the performance of dose calculation from the different systems (EGSnrc, Eclipse, and Pinnacle3), we needed to normalize the dose predictions to the same condition to reduce or minimize the contributions from other systematic differences not related to the dose algorithms, such as monitor unit (MU)∕dose value, head scatter model, and fluence model.4, 33 Our normalization method was similar to that described in the studies by Fogliata et al.4 and Knoos et al.33 For the AXB, AAA, and CCC algorithms, we prescribed the same 200 MU value for all plans in both homogeneous and heterogeneous phantoms. For AAA, we did not apply any normalization since they are in the same system and used the same beam model as AXB. To normalize the CCC to AXB, we used a depth of 10 cm (d10 cm) as the reference point. For each field, all dose results of CCC in the heterogeneous phantom were normalized to AXB according to the ratio of dose values at d10 cm in the homogeneous phantom. The normalization of MC is similar to that of CCC. For each field in the MC, instead of using the ratio of absolute dose value in CCC normalization, we calculated the ratios of the absolute dose per photon of MC to the absolute dose value of AXB at reference position d10 cm in the homogeneous phantom and applied these ratios to the heterogeneous dose predictions of MC to normalize it to AXB.

Both the depth and lateral dose profiles were compared between MC and AXB, AAA, or CCC for both homogenous and heterogeneous phantom. The dose difference was calculated as a percentage relative to the central axis (CAX) AXB dose.

For the volumetric comparison between AXB and AAA or CCC, 3D gamma indices relative to AXB were calculated based on the work of Wendling et al.34 The gamma index analysis was performed using IDL v7.1 (ITTVIS, Boulder, CO). Differences in the dose grids were reported as a percentage of global Dmax, which is the maximum dose in the field.35 It should be noted that this global dose difference criterion is less strict than assessment relative to local differences. The step size of the interpolation grid was set to 0.25 mm. The maximum search distance was 7 mm. The baseline criterion was 2% dose difference and 2 mm distance to agreement (DTA) (2%∕2 mm) since our comparisons were all between calculated doses. To further study the tolerance of dose difference to the passing rate, the gamma indices were plotted as a function of dose difference with a fixed DTA of 2 mm for the lung and inner beam region. For reference, we considered a 90% passing rate as the benchmark.4

All comparisons were separated into subregions to characterize the dose differences in more detail and avoid volume biasing. The four tissue regions in this slab phantom have been previously defined in the phantom description. We also defined four dose subregions similar to the AAPM TG-53 definitions:36 the buildup region corresponded to the voxels located from the entrance surface to the dmax (1.5 cm for 6 MV photon beams and 3.5 cm for 18 MV beams); the inner region corresponded to voxels with doses greater than 80% of the CAX AXB dose; the outer region corresponded to voxels with doses less than 20% of the CAX AXB dose; and the penumbra was defined as the voxels with doses between 80 and 20% of the CAX AXB dose.

RESULTS

Profiles in homogeneous phantom

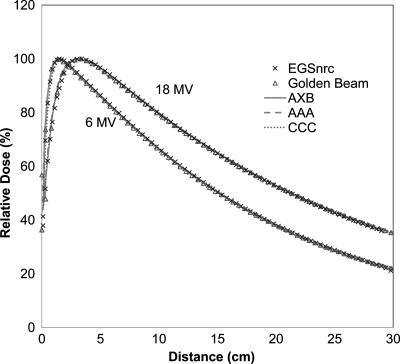

Figure 3 depicts the PDD curves calculated from MC, AXB, AAA, and CCC for both energies and field size of 10 × 10 cm2 in the homogeneous water phantom. The Varian golden beam data are also displayed as a reference. For 6 MV at depth from 1 to 30 cm, all the PDD voxels were in good agreement to the golden beam profiles (with the agreement within 1.5% relative to local CAX AXB dose). For 18 MV at depths from 2 to 30 cm, the calculated PDDs by all the algorithms were within 2.5% relative to CAX dose. Similar agreement was found for the other field sizes but not reported here for brevity.

Figure 3.

PDD profiles for 6 and 18 MV photon beams at a filed size of 10 × 10 cm2 in a homogeneous water phantom.

Figure 4 shows the lateral dose profiles at depth of dmax, 10 cm, and 20 cm for 6 and 18 MV photon beams for 10 × 10 cm2 field size. The agreements between all the algorithms and golden beam data are within 2% inside the beam for 6 MV. In high-gradient penumbra regions, the MC curve is relatively narrower due to the lack of head scatter. Similar effects were also found in 18 MV. In all these lateral dose profiles, the agreements between AXB and AAA or CCC were remarkable. Similar agreement was found for the other field sizes but not reported here for brevity.

Figure 4.

Lateral dose profiles at depths of dmax, 10 cm, and 20 cm for (a) 6 MV and (b) 18 MV photon beams at a field size of 10 × 10 cm2 in a homogeneous water phantom.

Profiles in heterogeneous phantom

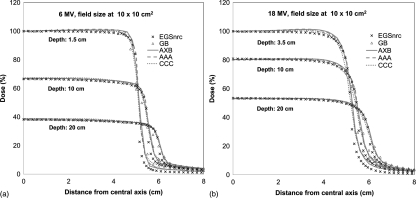

Figure 5 shows the depth dose profiles from MC, AXB, AAA, and CCC for both 6 and 18 MV beams in heterogeneous phantom. The grid size is 0.2 × 0.2 × 0.2 cm3 for the entire depth dose curve and 0.1 × 0.1 × 0.1 cm3 (AXB, AAA, and CCC) or 0.1 × 0.1 × 0.2 cm3 (MC) for the depth dose curve in the enlarged squares. The D(w,m) values for AXB and EGSnrc were also shown for comparison. Although the D(w,m) was almost the same as the D(m,m) in most tissues for both 6 and 18 MV beams, the differences in bone were found to be as large as 15.4%, which were expected according to the previous literatures.30, 37, 38 As mentioned above, since D(m,m) is the default dose reporting mode for AXB, theD(m,m) values were used for the remaining comparisons.

Figure 5.

Depth dose profiles in a heterogeneous slab phantom: 6 MV beams at field size of (a) 2.5 × 2.5, (b) 5 × 5, (c) 10 × 10 cm2; 18 MV beams at field size of (d) 2.5 × 2.5, (e) 5 × 5, (f) 10 × 10 cm2.

For 6 MV fields with depth > 1 cm, AXB and MC depth doses were in excellent agreement using either D(w,m) orD(m,m). The maximum relative differences were less than 1.5% relative to local dose for all voxels, and the average dose difference for all voxels was about 0.5% for the three field sizes. Conversely, AAA showed a larger disagreement with MC values. CCC appeared comparable to AXB but disagreed slightly with MC in some areas. Comparing with the D(m,m) of MC results, the maximum relative difference between AAA and MC was 6.6%. The average differences ranged from 2.1 to 3.9% for the three field sizes examined; the maximum relative difference between CCC and MC was 3.8% and the average difference was between 0.7 and 1.6%.

Agreement of depth doses between AXB and MC was slightly worse for 18 MV. Nevertheless, it is still within 2.0% for most dose voxels. The only exceptions were in the buildup region for 18 MV 10 × 10 cm2 field and a small rebuildup region in the second soft tissue for 18 MV 2.5 × 2.5 cm2. Similar to 6 MV, the AAA 18 MV fields showed a larger disagreement with MC, while CCC showed comparable but slightly larger differences than AXB. From Fig. 4b, it is obvious that the AAA and MC calculations were markedly different in the lung region for 18 MV 2.5 × 2.5 cm2 small fields; the maximum relative difference was 17.6%. For the same field size and lung region, the maximum relative difference between CCC and MC was 8.4%.

As depicted in the partial depth dose profiles in the enlarged square of Fig. 5, two peak-and-trough curves caused by backscatter effect could be found near the bone interfaces from both MC and AXB. However, AAA and CCC did not predict these steep dose-gradient changes. The dosimetric differences between AXB and MC at the interfaces were all within 2%, while AAA and CCC under- or overestimated the dose up to 8.3 and 4.8%, respectively.

Table Table I. lists the more detailed percent differences for the depth dose profiles in the various tissue regions defined by the slab phantom. Excellent agreement was found between AXB and MC (with an average dose difference < 1.1%). Both AAA and CCC showed larger disagreements with MC for all field sizes (with the average dose differences up to 4.4 and 2.2%, respectively). Again, the largest difference between MC and either AAA or CCC occurs in the lung region for 18 MV 2.5 × 2.5 cm2 field, with differences over the entire lung region reaching up to 11.6 and 4.5% for AAA and CCC.

Table 1.

Percent difference of depth dose curves between various dose algorithms and Monte Carlo simulations for different tissue regions defined in Fig. 2.

| 2.5 × 2.5 cm2 | 5 × 5 cm2 | 10 × 10 cm2 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage difference (%) | Tissues regions | AXB | AAA | CCC | AXB | AAA | CCC | AXB | AAA | CCC |

| 6 MV | ||||||||||

| (ΔD)maxa | Tissue 1b | 1.1 | 4.4 | 4.9 | 0.9 | 1.9 | 3 | 1.1 | 3.6 | 2.7 |

| Bone | 0.7 | 4.4 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 7.5 | 3.7 | 1.2 | 8.3 | 3.5 | |

| Lung | 1.1 | 6.6 | 3.8 | 1.4 | 4.4 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 5.1 | 1.1 | |

| Tissue 2 | 1.1 | 4.1 | 2.3 | 1.4 | 5.3 | 1.9 | 1.4 | 6.7 | 2.7 | |

| (ΔD)avg | Tissue 1b | 0.8 | 2 | 1.9 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.6 |

| Bone | 0.4 | 3.3 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 6.0 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 6.4 | 1.2 | |

| Lung | 0.6 | 3.1 | 2.1 | 0.4 | 2.8 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 3.0 | 0.6 | |

| Tissue 2 | 0.4 | 2.2 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 3.1 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 4.6 | 0.6 | |

| All | 0.5 | 2.5 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 3.1 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 3.9 | 0.7 | |

| 18 MV | ||||||||||

| (ΔD)max | Tissue 1b | 1.8 | 4.8 | 6.1 | 1.5 | 4.5 | 2.7 | 4.1 | 8.8 | 7.2 |

| Bone | 1.5 | 2.5 | 4 | 1.4 | 3.6 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 3.7 | 4.8 | |

| Lung | 1.8 | 17.6 | 8.4 | 1.8 | 2.6 | 3.8 | 1.3 | 4.8 | 4.3 | |

| Tissue 2 | 3.2 | 4.8 | 4.7 | 1.7 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 1.9 | 4.1 | 2.8 | |

| (ΔD)avg | Tissue 1b | 0.9 | 1.9 | 2.9 | 0.8 | 2.5 | 0.6 | 2.8 | 4.5 | 4.3 |

| Bone | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 1.6 | |

| Lung | 0.8 | 11.6 | 4.5 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 4.2 | 2.3 | |

| Tissue 2b | 1.2 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 0.8 | |

| All | 1 | 4.4 | 2.2 | 0.9 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 2.7 | 1.6 | |

ΔD = 100 × ABS(DXXX − DMC)∕DMC.

Part of the buildup region in tissue 1 was omitted (calculations only include depths > 1 cm for 6 MV and depths > 2 cm for 18 MV), where the large difference is due to its large dose gradient and source model of EGSnrc.

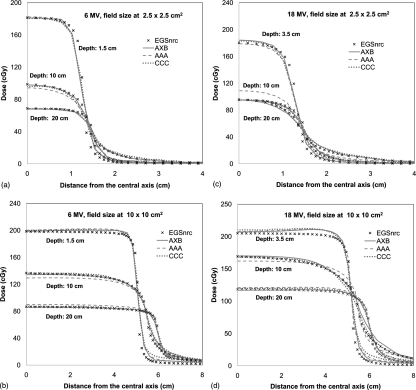

The lateral dose profiles for the 6 and 8 MV photon beams in heterogeneous slab phantom were compared in Fig. 6. Only the 2.5 × 2.5 cm2 and 10 × 10 cm2 were shown for brevity. For each field size, three lateral dose profiles at depths of 1.5 (dmax), 10, and 20 cm were compared. Generally, the profiles from AXB are closer to MC than both AAA and CCC. For 6 MV photon beam, the average differences of lateral dose profiles (0–4 cm for 2.5 × 2.5 cm2 field, 0–8 cm for 10 × 10 cm2) for all the field sizes were within 1.6, 2.8, and 1.9% for AXB, AAA, and CCC, respectively. For 18 MV, these differences were 3.2, 5.7, and 3.8%. The AAA shows a large overestimation in depth of 10 cm, which is located in the lung region. However, it should be noted that the differences of lateral dose profiles between MC and AXB, AAA, or CCC in 18 MV might be attributed to the different beam model since the effects of head scatter and electronic contamination are more serious for the 18 MV photon beam.

Figure 6.

Lateral dose profiles at depths of dmax, 10 cm, and 20 cm in a heterogeneous slab phantom: (left) 6 MV beams at field sizes of (a) 2.5 × 2.5 cm2 and (b) 10× 10 cm2; (right) 18 MV beams for field sizes of (c) 2.5 × 2.5 cm2 and (d) 10 × 10 cm2.

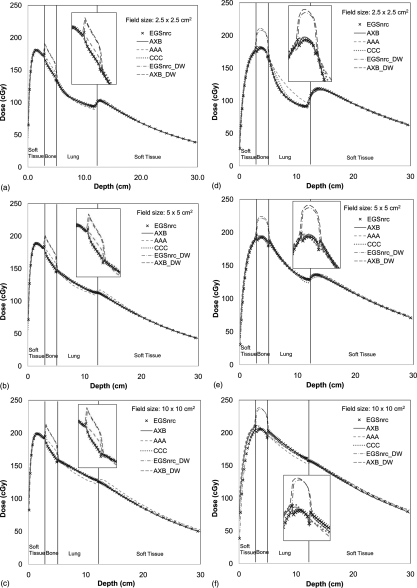

3D gamma analysis

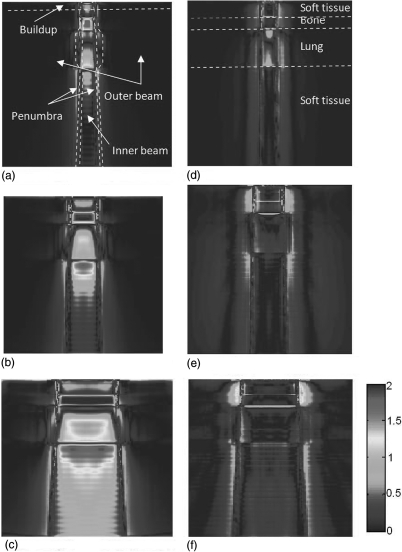

The agreement of AXB with AAA and CCC was evaluated using 3D gamma index analysis. The evaluation used acceptability criterion of a 2% dose difference and 2 mm DTA. The spatial distributions of the gamma index of the central plane were shown in Fig. 7 for 6 MV and Fig. 8 for 18 MV. From these figures, we found that the differences between AXB and AAA or CCC were distributed divergently depending on the energies and field sizes. For AAA at both energies, there were a notable number of voxels in the bone and lung regions did not pass the 2%∕2 mm DTA criterion. For CCC, the difference to AXB in 6 MV beam is very small. However, the CCC has notable differences for 18 MV, especially in the lung and buildup regions. More detailed numbers were listed in Table Table II. for 6 MV and Table Table III. for 18 MV.

Figure 7.

Gamma index (2%∕2 mm) of dose distributions in the central slice for 6 MV: (left) AAA versus AXB at field sizes of (a) 2.5 × 2.5 cm2, (b) 5 × 5 cm2, and (c) 10 × 10 cm2; and (right) CCC versus AXB at field sizes of (d) 2.5 × 2.5 cm2, (e) 5 × 5 cm2, and (f) 10 × 10 cm2. The TG-53 regions and the tissue regions are shown in (a) and (d), respectively.

Figure 8.

Gamma index (2%∕2 mm) of dose distributions in the central slice for 18 MV: (left) AAA versus AXB at field sizes of (a) 2.5 × 2.5 cm2, (b) 5 × 5 cm2, and (c) 10 × 10 cm2; and (right) CCC versus AXB at field sizes of (d) 2.5 × 2.5 cm2, (e) 5 × 5 cm2, and (f) 10 × 10 cm2. The TG-53 regions and the tissue regions are shown in (a) and (d), respectively.

Table 2.

The percentage passing rate of 3D gamma indices of AAA and CCC compared to AXB in tissue regions defined in Fig. 2 and TG-53 subregions (Ref. 36) for 6 MV beams.

| 2.5 × 2.5 cm2 | 5 × 5 cm2 | 10 × 10 cm2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criterion | Tissue region | TG 53 Subregion | AAA∕AXB | CCC∕AXB | AAA∕AXB | CCC∕AXB | AAA∕AXB | CCC∕AXB | |

| γ (2%∕2 mm) | Buildupa | All | 99.9 | 100.0 | 99.7 | 99.3 | 94.8 | 97.4 | |

| Tissue 1 | Inner | 99.9 | 90.4 | 99.8 | 87.7 | 100.0 | 96.1 | ||

| Outer | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 98.5 | 100.0 | 93.1 | |||

| Penumbra | 97.4 | 98.3 | 100.0 | 99.5 | 85.8 | 99.9 | |||

| Bone | Inner | 58.2 | 100.0 | 31.3 | 99.8 | 14.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Outer | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 99.2 | 100.0 | 94.3 | |||

| Penumbra | 83.0 | 99.5 | 99.6 | 100.0 | 88.0 | 99.8 | |||

| Lung | Inner | 86.8 | 98.9 | 75.0 | 99.0 | 51.0 | 99.7 | ||

| Outer | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |||

| Penumbra | 99.9 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 99.9 | 100.0 | |||

| Tissue 2 | Inner | 100.0 | 100.0 | 91.0 | 100.0 | 76.1 | 100.0 | ||

| Outer | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |||

| Penumbra | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |||

| All | Inner | 94.6 | 99.5 | 85.0 | 99.2 | 69.2 | 99.7 | ||

| Outer | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.1 | |||

| Penumbra | 99.3 | 99.9 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 98.8 | 100.0 | |||

Partially overlaps with buildup for 6 MV beams. Note: 3D gamma indices %passing = 100 × (# of gamma indices ≤ 1.0)∕(# of total voxels).

Table 3.

The percentage passing rate of 3D gamma indices of AAA and CCC compared to AXB in tissue regions defined in Fig. 2 and TG-53 subregion (Ref. 36) for 18 MV beams.

| 2.5 × 2.5 cm2 | 5 × 5 cm2 | 10 × 10 cm2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criterion | Tissue region | TG 53 Subregion | AAA∕AXB | CCC∕AXB | AAA∕AXB | CCC∕AXB | AAA∕AXB | CCC∕AXB |

| γ (2%∕2 mm) | Buildup | All | 100.0 | 100.0 | 99.6 | 98.0 | 97.1 | 88.1 |

| Tissue 1a | Inner | 100.0 | 100.0 | 95.8 | 79.4 | 91.3 | 87.0 | |

| Outer | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 97.9 | ||

| Penumbra | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 99.9 | 99.8 | 100.0 | ||

| Boneb | Inner | 100.0 | 100.0 | 99.5 | 63.7 | 100.0 | 65.4 | |

| Outer | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 99.1 | 100.0 | 98.1 | ||

| Penumbra | 95.7 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 99.3 | 100.0 | ||

| Lung | Inner | 6.6 | 91.1 | 58.7 | 92.9 | 41.1 | 26.2 | |

| Outer | 99.3 | 100.0 | 98.1 | 100.0 | 96.0 | 99.7 | ||

| Penumbra | 88.4 | 100.0 | 63.7 | 100.0 | 45.0 | 86.5 | ||

| Tissue 2 | Inner | 98.9 | 100.0 | 99.1 | 100.0 | 94.7 | 100.0 | |

| Outer | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Penumbra | 100.0 | 100.0 | 99.8 | 100.0 | 99.0 | 100.0 | ||

| All | Inner | 82.2 | 98.3 | 91.9 | 95.4 | 85.3 | 84.4 | |

| Outer | 99.8 | 100.0 | 99.5 | 99.8 | 98.9 | 98.3 | ||

| Penumbra | 96.0 | 100.0 | 86.8 | 98.8 | 77.2 | 93.1 |

Overlaps with buildup for 18 MV beams.

Partially overlap with buildup region for 18 MV beams.

In Table Table II., the percentage of voxels with passing gamma indices in the tissue regions and TG-53 subregions for 6 MV beam are shown. For the voxels inside the inner beam region, 69.2%–94.6% of AAA dose values were found to pass the 2%∕2 mm gamma criterion. The differences mainly occurred in the bone and lung regions. CCC has a high passing rate for 6 MV, with over 99% of voxels for all subregions passing the 2%∕2 mm criterion. For the penumbra and outer beam region, both AAA and CCC have high passing rates for all field sizes and tissue regions.

The passing rates of gamma indices for 18 MV beam are listed in Table Table III.. For the inner beam region, 82.2%–91.9% of AAA dose voxel values were found to pass the 2%∕2 mm DTA criterion. The differences of AAA to AXB for 18 MV beam mainly occurred in the lung region. For CCC, the passing rates for 18 MV were lower than 6 MV, especially for 10 × 10 cm2 field size in the lung region and for 5 × 5 cm2 and 10 × 10 cm2 field sizes in the bone region. For both AAA and CCC, the differences in penumbra were larger than those in 6 MV; in particular, for the 10 × 10 cm2 field size in the lung penumbral region, the passing rates were 45 and 86.5% for AAA and CCC, respectively.

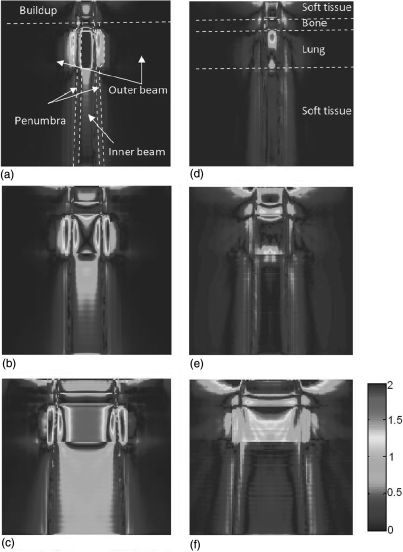

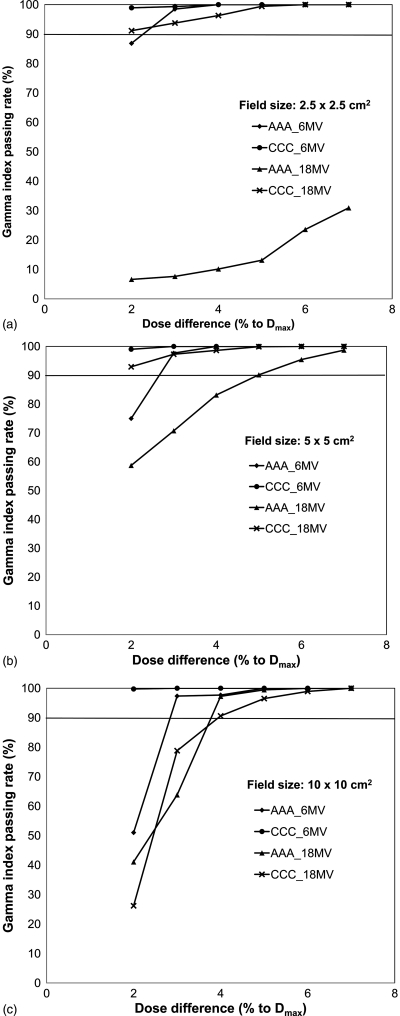

To further study the tolerance of dose difference to the passing rate, the gamma indices were plotted as a function of dose difference with a fixed DTA of 2 mm in Fig. 9 for the inner lung region. With less stringent dose difference criterion, the percentage of passing voxels increased as expected. For instance, if 90% passing as a benchmark for 2 mm DTA was used, we found that AAA can reach this pass criterion with a dose difference of 3% for all 6 MV field sizes. While for 18 MV, this threshold increased to 4 and 6% for the 10 × 10 and 5 × 5 cm2 fields, respectively. However, for the 2.5 × 2.5 cm2 small field, AAA did not reach the 90% passing rate. The dose difference threshold for this case to be achieved must be >7%. For CCC, most of the plans have over 90% passing with 2% dose difference except for the 18 MV 10 × 10 cm2 field, in which the threshold of dose difference between CCC and AXB needed to be increased to 4% to reach the 90% passing rate. Figure 10 shows the same analysis for the entire inner beam region. Similar trends were observed in this region.

Figure 9.

Percentage of voxels passing gamma index versus dose difference under a fixed DTA of 2 mm inside the lung region for different field sizes: (a) 2.5 × 2.5 cm2, (b) 5 × 5 cm2, and (c) 10 × 10 cm2. 90% passing rate is considered as a benchmark.

Figure 10.

Percentage of voxels passing gamma index versus dose difference under a fixed DTA of 2 mm throughout the entire inter beam region for different field sizes: (a) 2.5 × 2.5 cm2, (b) 5 × 5 cm2, and (c) 10 × 10 cm2. 90% passing rate is considered as a benchmark.

Computation time

For clinical use, both accuracy and computation time are important factors. The Eclipse system used in this study, which contains the AXB and AAA algorithms, was installed on a standard clinical workstation (Dell T5500) with dual 2.27-GHz quad-core Intel processors E5520, 24 GB RAM memory, and a 64-bit Windows XP operating system (OS). The Pinnacle3 CCC v9 was on an in-house system with a 2.8-GHz dual-core AMD 8220 Opteron, 64 GB RAM memory, and a Solaris x86 OS. Table Table IV. depicts the real computation times for all plans. The AAA had the shortest time among these three methods. AXB times were comparable to CCC for the small field 2.5 × 2.5 cm2 plans but were about 5× longer for 10 × 10 cm2 field. It should be noted that computation times vary based on hardware and working conditions such as if users have other programs running or if the antivirus software was turned on.

Table 4.

Computation times of the various algorithms investigated in this study.

| Water phantom computation time (s) | Slab phantom computation time (s) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beam energy | Field size (cm2) | AXB | AAA | CCC | AXB | AAA | CCC |

| 6 MV | 2.5 × 2.5 | 94 | 7 | 51 | 113 | 7 | 90 |

| 5 × 5 | 112 | 7 | 53 | 136 | 7 | 91 | |

| 10 × 10 | 217 | 8 | 54 | 286 | 9 | 90 | |

| 18 MV | 2.5 × 2.5 | 181 | 7 | 54 | 216 | 7 | 90 |

| 5 × 5 | 184 | 8 | 54 | 233 | 9 | 89 | |

| 10 × 10 | 340 | 9 | 55 | 474 | 11 | 91 |

Note: Grid sizes in both phantoms (30 × 30 × 30 cm3) are 2.0 × 2.0 × 2.0 mm3.

DISCUSSION

The accuracy of dose calculations is essential to the quality of the radiotherapy treatment planning and tumor response.5, 39 Evidence exists that a 1% accuracy improvement results in 2% increase in cure rate for early stage tumors.40 Moreover, several studies have shown that if the prescribed dose falls along the steepest region of the dose-effect curves, 5% changes in local dose can result in a 10%−20% change in local tumor control probability or up to a 30% change in normal tissue complication probability.10 Thus, the potential impact of an improved dose algorithm is fundamental in clinical output.

In this study, a preclinical version of AXB, a novel deterministic algorithm, which was recently made available to the medical physics community, was validated and compared with MC and clinical convolution methods. By comparing the depth dose and lateral dose profiles of conventional external photon beams in both a homogeneous water and a multilayer slab phantoms, we found that the dose agreement of AXB to MC for almost all voxels was within 2%, indicating that the AXB was comparable to MC for dose prediction. We also found that AAA dose predictions differ from MC up to 11.6% in the lung region for the 18 MV 2.5 × 2.5 cm2 field. Conversely, CCC has slightly larger differences relative to MC than AXB (up to 4.5% in the lung region). Fogliata et al. previously compared various dose calculation algorithms, such as AAA v7.5 in Eclipse and CCC in Pinnacle3 7.6, for a different simple geometric phantom.4 They also reported large dose deviation for the AAA algorithm in the lung region, which is consistent with our findings.

Our detailed 3D comparison between AXB and AAA and CCC provided useful insights. The rationale for such comparisons is that most clinical TPSs currently use either AAA or CCC for patient treatment planning. Therefore, any new dose algorithm must be compared with these algorithms to realize the differences under well-controlled conditions. Our results showed that, in most of the beam regions, both AAA and CCC have acceptable agreement with AXB (90% of dose voxels passing 5%∕2 mm). However, there were still some notable differences (lower than 90% voxels passed 2%∕2 mm criterion) in various subregions, which one should be aware of when transitioning to AXB clinical practices:

For the lung region inside the field:

-

(1)

The dose differences between AAA and AXB are significant (less than 60% voxels passed 2%∕2 mm criterion) for all fields of 18 MV and 10 × 10 cm2 field of 6 MV. For the 18 MV 2.5 × 2.5 cm2 field, the difference can be up to 17.6% and the gamma passing rate in this region was less than 10% for the 2%∕2 mm criterion and less than 40% for the 5%∕2 mm criterion. This difference was expected since similar findings were reported in the literature between AAA and MC for 15 MV photon beams.4

-

(2)

The CCC and AXB showed significant differences in the 18 MV 10 × 10 cm2 field. However, for the 18 MV 2.5 × 2.5 cm2 field, although the gamma analysis indicated a pass rate of ∼91% between CCC and AXB, a depth dose analysis showed that the CCC dose predictions were up to 8% higher than AXB in the lung region.

For the bone region inside the field:

-

(1)

AAA and AXB showed significant differences for all field sizes investigated with the 6 MV photon beam but excellent agreement was found for the 18 MV photon beam for all fields. The large differences between AAA and AXB in the bone region had been expected due to AAA dose report mode (D(w,m)). However, from our results, AAA actually exhibited better agreement with D(m,m) than D(w,m) from MC or AXB especially for 18 MV, as shown in Fig. 4. It seems that the D(w,m) from AAA and D(m,m) from other algorithms have no difference in essence. The definition of dose report modes are somewhat different between vendors, which might lead to confusion. Similar concerns were also stated in the paper by Fogliata et al.4 Based on above results, those differences in the bone region between AAA and AXB were mainly due to the radiation transport.

More generally, it is currently controversial whether radiation dose should be reported as dose-to-water or dose-to-medium. In most clinical dose algorithms, only one dose mode is available. Although the difference between these two report modes very small in most tissues, it can be up to about 15% in bone, as shown in this study and previous literature.30, 38 The dose-to-medium mode is used as the default in AXB since it solves the LBTE for specific materials in a patient. However, AXB also provides an option for reporting the dose-to-water. By doing this, it provides a platform for further studies for investigating this issue.

-

(2)

The differences between AXB and CCC are notable in 18 MV 5 × 5 cm2 and 10 × 10 cm2 fields. If the criterion is relaxed to 3%∕2 mm, the passing rate will increase above 90% for both fields.

For the buildup and penumbra region:

-

(1)

Since AAA and AXB are from the same Eclipse system and have the same beam model, AAA showed relatively small difference in buildup region. However, there are still notable differences to AXB in the penumbra regions near the lung for 18 MV, as indicated in Fig. 8. These differences are attributed to the radiation transport method that AXB is using to accurately model the radiation scatter inside the patient.

-

(2)

Compared to AAA, CCC shows smaller differences with AXB in the penumbra region, but larger differences in the buildup region for 18 MV. The differences increased with the larger field sizes. Considering that the AXB and CCC are from different system, this might be due to differences in beam models between Eclipse and Pinnacle3.

In general, the dose calculation uncertainties of both AAA and CCC occur at interfaces of materials with different densities, especially when one of the materials is bone. As shown in Fig. 4, there are obvious dose peaks or troughs near the bone interface for both MC and AXB; however, neither AAA nor CCC predicts these phenomena. This limitation of the convolution method for interface dosimetry is due to its inability to model the coupled photon–electron transport across the interface: backscattered photons, backscattered secondary electrons originating from the upstream tissue, and backscattered secondary electrons originating from the downstream tissue. This is noticeable at interfaces with large density differences and∕or different atomic numbers. AXB predictions of interface dosimetry were comparable to those from MC, which was expected since AXB is a GBBS with full physics modeling of photon and electron radiation transport. This feature could be very important for some lung cancer patients with tumors located close to the chest wall. In those cases, a radiation plan derived using convolution methods might lead to a larger dose bias. However, the clinical significance of using AXB in this case still needs to be studied in more detail.

In this study, we are aware of our MC simulation limitations using a simplified head model. Thus, the differences between AXB with MC were larger in the buildup region than our previous study for validation of prototype version Acuros.18 Considering the difficulty of modeling of real clinical head model41 and the consistency with the previous study, the MC dose prediction from this simplified model still was a reasonable benchmark with the head model effects being considered during the comparison.

With sufficient refinement, both MC and AXB are expected to converge to the same dose predictions.42 The achievable accuracy of both methods is potentially equivalent and only constrained by the available computational resources. For practical reasons, a limited number of histories are possible for a MC simulation, and a limited finite sampling of the energy groups, beam angles, and beam geometries is possible for AXB. Based on our initial experiences, the AXB algorithm achieved a comparable computation time with the clinically used CCC algorithm for small field dosimetry. Furthermore, the computation time of AXB might be further reduced by implementation on graphical processing units and additional refinements. It also should be mentioned that, in creating more realistic clinical treatment plans for intensity-modulated radiotherapy or volumetric modulated arc therapy, AXB has only a weak dependence on the number of beams.43 This is mostly due to the fact that the primary source (uncollided) component needs to be calculated for each beam via ray tracing, whereas the scatter components are calculated only once regardless of the number of beam angles. Thus, AXB can provide both high accuracy and relatively fast calculation times for volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) radiotherapy.

CONCLUSION

The AXB advanced dose calculation algorithm integrated in the Eclipse TPS produced dose accuracy comparable to the MC method for a challenging heterogeneous phantom. In particular, we found that AXB could improve the dose prediction accuracy over both AAA and CCC for the bone and lung regions. AXB dose predictions near an interface are in closer agreement to MC than currently used convolution methods. The computation times of AXB are comparable to CCC in small fields open beam. Since there has been an increased demand for dose calculation accuracy in advanced radiotherapy using small fields (such as VMAT) in highly heterogeneous regions (such as the lung or head and neck),44, 46 the AXB algorithm’s balance of both accuracy and computation speed shows promise for future dose calculations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health through Grant Nos. 2R44CA105806-02 and MD Anderson’s Cancer Center Support Grant No. CA016672. The authors thank Stephen K. Thompson, Pekka Uusitalo, Laura Korhonen, and Tuomas Torsti from Varian Medical System and Gregory A. Failla, Todd A. Wareing, and John McGhee from Transpire, Inc., for providing the prototype version of the Eclipse system. The authors also thank Milos Vicic and Ramesh Tailor from the Radiation Physics Department at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center for help with the Pinnacle3 TPS and small-field output factors, respectively.

References

- Ahnesjo A. and Aspradakis M. M., “Dose calculations for external photon beams in radiotherapy,” Phys. Med. Biol. 44, 99–155 (1999). 10.1088/0031-9155/44/11/201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huyskens D., Van Esch A., Pyykkonen J., Tenhunen M., Hannu Helminen H., Tillikainen L., Siljamaki S., and Alakuijala J., “Improved photon dose calculation in the lung with the analytical anisotropic algorithm (AAA),” Radiother. Oncol. 81, S513 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahnesjo A., “Collapsed cone convolution of radiant energy for photon dose calculation in heterogeneous media,” Med. Phys. 16, 577–592 (1989). 10.1118/1.596360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogliata A., Vanetti E., Albers D., Brink C., Clivio A., Knoos T., Nicolini G., and Cozzi L., “On the dosimetric behaviour of photon dose calculation algorithms in the presence of simple geometric heterogeneities: comparison with Monte Carlo calculations,” Phys. Med. Biol. 52, 1363–1385 (2007). 10.1088/0031-9155/52/5/011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papanikolaou N B. J., Boyer A, Kappas C, Klein E, Mackie T, Sharpe J, and Van Dyke J., “Tissue inhomogeneity corrections for megavoltage photon beams,” AAPM Report No. 85 (2004).

- Tillikainen L., Helminen H., Torsti T., Siljamaki S., Alakuijala J., Pyyry J., and Ulmer W., “A 3D pencil-beam-based superposition algorithm for photon dose calculation in heterogeneous media,” Phys. Med. Biol. 53, 3821–3839 (2008). 10.1088/0031-9155/53/14/008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillikainen L., Siljamaki S., Helminen H., Alakuijala J., and Pyyry J., “Determination of parameters for a multiple-source model of megavoltage photon beams using optimization methods,” Phys. Med. Biol. 52, 1441–1467 (2007). 10.1088/0031-9155/52/5/015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawrakow I., Fippel M., and Friedrich K., “3D electron dose calculation using a Voxel based Monte Carlo algorithm (VMC),” Med. Phys. 23, 445–457 (1996). 10.1118/1.597673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C. M., Mok E., Kapur A., Pawlicki T., Findley D., Brain S., Forster K., and Boyer A. L., “Clinical implementation of a Monte Carlo treatment planning system,” Med. Phys. 26, 2133–2143 (1999). 10.1118/1.598729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chetty I. J., Curran B., Cygler J. E., DeMarco J. J., Ezzell G., Faddegon B. A., Kawrakow I., Keall P. J., Liu H., Ma C. M. C., Rogers D. W. O., Seuntjens J., Sheikh D.-Bagheri, and Siebers J. V., “Report of the AAPM Task Group No. 105: Issues associated with clinical implementation of Monte Carlo-based photon and electron external beam treatment planning,” Med. Phys. 34, 4818–4853 (2007). 10.1118/1.2795842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer A. L., Butler E. B., DiPetrillo T. A., Engler M. J., Fraass B., Grant W., Ling C. C., Low D. A., Mackie T. R., Mohan R., Purdy J. A., Roach M., Rosenman J. G., Verhey L. J., Wong J. W., Cumberlin R. L., Stone H., Palta J. R., and Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy Collaborative Working Group, “Intensity-modulated radiotherapy: Current status and issues of interest,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 51, 880–914 (2001). 10.1016/S0360-3016(01)01749-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzell G. A., Galvin J. M., Low D., Palta J. R., Rosen I., Sharpe M. B., Xia P., Xiao Y., Xing L., and Yu C. X., “Guidance document on delivery, treatment planning, and clinical implementation of IMRT: Report of the IMRT subcommittee of the AAPM radiation therapy committee,” Med. Phys. 30, 2089–2115 (2003). 10.1118/1.1591194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto K., “Volumetric modulated arc therapy: IMRT in a single gantry arc,” Med. Phys. 35, 310–317 (2008). 10.1118/1.2818738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffray D. A., Siewerdsen J. H., Wong J. W., and Martinez A. A., “Flat-panel cone-beam computed tomography for image-guided radiation therapy,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 53, 1337–1349 (2002). 10.1016/S0360-3016(02)02884-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford K. A., Horton J. L., Wareing T. A., Failla G., and Mourtada F., “Comparison of a finite-element multigroup discrete-ordinates code with Monte Carlo for radiotherapy calculations,” Phys. Med. Biol. 51, 2253–2265 (2006). 10.1088/0031-9155/51/9/010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford K. A., Price M. J., Horton J. L., Wareing T. A., and Mourtada F., “Optimization of deterministic transport parameters for the calculation of the dose distribution around a high dose-rate Ir-192 brachytherapy source,” Med. Phys. 35, 2279–2285 (2008). 10.1118/1.2919074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassiliev O. N., Wareing T. A., Davis I. M., McGhee J., Barnett D., Horton J. L., Gifford K., Failla G., Titt U., and Mourtada F., “Feasibility of a multigroup deterministic solution method for three-dimensional radiotherapy dose calculations,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 72, 220–227 (2008). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.04.057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassiliev O. N., Wareing T. A., McGhee J., Failla G., Salehpour M. R., and Mourtada F., “Validation of a new grid-based Boltzmann equation solver for dose calculation in radiotherapy with photon beams,” Phys. Med. Biol. 55, 581–598 (2010). 10.1088/0031-9155/55/3/002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drumm C. R., “Multidimensional electron-photon transport with standard discrete ordinates codes,” Nucl. Sci. Eng. 127, 1–21 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Daskalov G. M., Baker R. S., Rogers D. W. O., and Williamson J. F., “Dosimetric modeling of the microselectron high-dose rate Ir-192 source by the multigroup discrete ordinates method,” Med. Phys. 27, 2307–2319 (2000). 10.1118/1.1308279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg D. W., Randolph P. D., and Wheeler F. J., “Demonstration of three-dimensional deterministic radiation transport theory dose distribution analysis for boron neutron capture therapy,” Med. Phys. 18, 43–53 (1991). 10.1118/1.596721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D. Rogers W. O. and Mohan R., Questions for Comparison of Clinical Monte Carlo Codes (Springer-Verlag Berlin, Berlin, 2000). [Google Scholar]

- Eclipse Algorithms Reference Guide (Varian medical system, Palo Alto, CA, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- Beam Configuration Reference Guide (Varian medical system, Palo Alto, CA, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- Walters W. F., Use of the Chebyshev-Legendre Quadrature Set in Discrete-Ordinate Codes (Los Alamos National Lab, NM, 1987). [Google Scholar]

- Rogers D. W. O., Faddegon B. A., Ding G. X., Ma C. M., We J., and Mackie T. R., “BEAM: A Monte Carlo code to simulate radiotherapy treatment units,” Med. Phys. 22, 503–524 (1995). 10.1118/1.597552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters B., Kawrakow I., and Rogers D.W.O., DOSXYZnrc Users Manual (National Research Council of Canada, Ottawa, Canada, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- Cho S. H., Vassiliev O. N., Lee S., and Liu H. H., “Reference photon dosimetry data and reference phase space data for the 6 MV photon beam from Varian Clinac 2100 series linear accelerators,” Med. Phys. 32, 137–148 (2005). 10.1118/1.1829172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassiliev O. N., Titt U., Kry S. F., Ponisch F., Gillin M. T., and Mohan R., “Monte Carlo study of photon fields from a flattening filter-free clinical accelerator,” Med. Phys. 33, 820–827 (2006). 10.1118/1.2174720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebers J. V., Keall P. J., Nahum A. E., and Mohan R., “Converting absorbed dose to medium to absorbed dose to water for Monte Carlo based photon beam dose calculations,” Phys. Med. Biol. 45, 983–995 (2000). 10.1088/0031-9155/45/4/313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterpin E., Tomsej M., De Smedt B., Reynaert N., and Vynckier S., “Monte Carlo evaluation of the AAA treatment planning algorithm in a heterogeneous multilayer phantom and IMRT clinical treatments for an Elekta SL25 linear accelerator,” Med. Phys. 34, 1665–1677 (2007). 10.1118/1.2727314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fotina I., Winkler P., Kunzler T., Reiterer J., Simmat I., and Georg D., “Advanced kernel methods vs. Monte Carlo-based dose calculation for high energy photon beams,” Radiother. Oncol. 93, 645–653 (2009). 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoos T., Wieslander E., Cozzi L., Brink C., Fogliata A., Albers D., Nystrom H., and Lassen S., “Comparison of dose calculation algorithms for treatment planning in external photon beam therapy for clinical situations,” Phys. Med. Biol. 51, 5785–5807 (2006). 10.1088/0031-9155/51/22/005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendling M., Zijp L. J., McDermott L. N., Smit E. J., Sonke J. J., Mijnheer B. J., and Van Herk M., “A fast algorithm for gamma evaluation in 3D,” Med. Phys. 34, 1647–1654 (2007). 10.1118/1.2721657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low D. A., Harms W. B., Mutic S., and Purdy J. A., “A technique for the quantitative evaluation of dose distributions,” Med. Phys. 25, 656–661 (1998). 10.1118/1.598248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraass B., Doppke K., Hunt M., Kutcher G., Starkschall G., Stern R., and Van Dyke J., “American Association of Physicists in Medicine radiation therapy committee task group 53: Quality assurance for clinical radiotherapy treatment planning,” Med. Phys. 25, 1773–1829 (1998). 10.1118/1.598373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogan N., Siebers J. V., and Keall P. J., “Clinical comparison of head and neck and prostate IMRT plans using absorbed dose to medium and absorbed dose to water,” Phys. Med. Biol. 51, 4967–4980 (2006). 10.1088/0031-9155/51/19/015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters B. R. B., Kramer R., and Kawrakow I., “Dose to medium versus dose to water as an estimator of dose to sensitive skeletal tissue,” Phys. Med. Biol. 55, 4535–4546 (2010). 10.1088/0031-9155/55/16/S08 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutreix A., “When and how can we improve precision in radiotherapy?,” Radiother. Oncol. 2, 275–292 (1984). 10.1016/S0167-8140(84)80070-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer A. L. and Schultheiss T., “Effects of dosimetric and clinical uncertainty on complication-free local tumor control,” Radiother. Oncol. 11, 65–71 (1988). 10.1016/0167-8140(88)90046-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das I. J. and Kahn F. M., “Backscatter dose perturbation at high atomic number interfaces in megavoltage photon beams,” Med. Phys. 16, 367–375 (1989). 10.1118/1.596345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keall P. J., Siebers J. V., Libby B., and Mohan R., “Determining the incident electron fluence for Monte Carlo-based photon treatment planning using a standard measured data set,” Med. Phys. 30, 574–582 (2003). 10.1118/1.1561623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgers C., “Complexity of Monte Carlo and deterministic dose-calculation methods,” Phys. Med. Biol. 43, 517–528 (1998). 10.1088/0031-9155/43/3/004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassiliev O., Wareing T., McGhee J., Failla G., Salehpour M., and Mourtada F., “SU-EE-A2-2: Validation of a grid-based Boltzmann solver for 6 and 18 MV photon beams impinging on a heterogeneous phantom,” in AAPM (AAPM, Anaheim, CA, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- Mans A., Remeijer P., Olaciregui-Ruiz I., Wendling M., Sonke J. J., Mijnheer B., van Herk M., and Stroom J. C., “3D Dosimetric verification of volumetric-modulated arc therapy by portal dosimetry,” Radiother. Oncol. 94, 181–187 (2010). 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath S. D., Matuszak M. M., Yan D., Kestin L. L., Martinez A. A., and Grills I. S., “Volumetric modulated arc therapy for delivery of hypofractionated stereotactic lung radiotherapy: A dosimetric and treatment efficiency analysis,” Radiother. Oncol. 95, 153–157 (2010). 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.12.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]