Abstract

Mass spectrometry (MS) – based proteomic approaches have evolved as powerful tools for the discovery of biomarkers. However, the identification of potential protein biomarkers from biofluid samples is challenging because of the limited dynamic range of detection. Currently there is a lack of sensitive and reliable pre-mortem diagnostic test for prion diseases. Here, we describe the use of a combined MS-based approach for biomarker discovery in prion diseases from mouse plasma samples. To overcome the limited dynamic range of detection and sample complexity of plasma samples, we used lectin affinity chromatography and multi-dimensional separations to enrich and isolate glycoproteins at low abundance. Relative quantitation of a panel of proteins was obtained by a combination of isotopic labeling and validated by spectral counting. Overall 708 proteins were identified, 53 of which showed more than 2-fold increase in concentration whereas 58 exhibited more than 2-fold decrease. A few of the potential candidate markers were previously associated with prion or other neurodegenerative diseases.

Keywords: Prion disease, biomarkers, glycoprotein, mass spectrometry, proteomics, quantitation, multi-dimensional separation

Introduction

Prion diseases, also known as transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), are a unique group of neurodegenerative diseases of the central nervous system, which include bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) in cattle, scrapie in sheep, chronic wasting disease (CWD) in deer. Human forms of the prion diseases include: genetic disease, Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker syndrome and fatal familial insomnia; sporadic disease, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), and infectious disease, variant CJD (vCJD), caused by the consumption of BSE infected cattle, and kuru, linked to the practice of ritualistic cannibalism in Papua New Guinea. Although the species barrier provides significant protection from the interspecies transmission of prion disease, the outbreaks of BSE epidemic and the resulting rise in vCJD illustrates the potential impact of prion disease upon human and economic health.

TSEs are caused by the conversion of a normal cellular prion protein (PrPc) into an abnormal form (PrPSc)1, 2. PrPC is a 33–35 kDa protein encoded by a single copy gene3, 4. During the course of a scrapie infection, PrPC undergoes a post-translational conformational conversion to disease-specific isoforms (PrPSc) that have increased resistance to proteinase K digestion. In vitro cell culture studies have suggested that PrPC is the precursor to infectious isoform1. Disease specific PrPSc isoforms are present in various types of tissues but predominantly in the brain tissue and spinal cord at terminal stages of disease. Clinical symptoms of affected animals generally include pruritus, ataxia, and ultimately, death following an extended asymptomatic incubation period of months to decades during which infectious agent can replicate to very high titers (>1 × 108 infectious units per gram)1, 2. Histopathological features of TSEs are characterized by spongiform degeneration, reactive astrocytosis, and the accumulation of aggregated prion proteins in the central nervous system.

Currently validated diagnostic tests for prion diseases are all post-mortem. Confirmation of the disease is carried out by the observation of characteristic vacuolar or spongiform changes in specific areas of the brain by histopathological examination of fixed brain sections using light microscopy. The “gold standard” in prion diagnostic testing is immunohistochemistry utilizing anti-prion protein antibodies on the obex region of the brain 5. Despite the good specificity and sensitivity of these tests, animals infected with prion disease can only be diagnosed late in the pre-clinical period when sufficient abnormal PrPSc has accumulated in brain tissue. Pre-mortem tests that allow early detection of infection would reduce the risk of infected animals entering the marketplace, prevent unnecessary slaughtering of healthy animals, enable accurate prediction of TSE epidemic, and improve our understanding of the disease, thereby facilitating the development of effective treatments.

Development of non-prion protein biomarkers for TSEs has resulted in the identifications of surrogate markers in patients presenting clinical signs of CJD. Elevated levels of central nervous system-specific proteins such as 14-3-3, tau, apolipoprotein E, cystatin C, and neuron-specific enolase have been observed in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or brains of patients 6–12. The identification of biomarkers from more readily available sample sources such as blood plasma, however, remains challenging, due to the inherent complexity and vast dynamic range of proteins in the samples.

In the post-genomic era, there has been a growing interest in applying MS-based proteomics technology to research on biomarker discovery and clinical diagnostics of diseases such as cancers and neurodegenerative disorders from blood plasma. The current bottleneck of discovering biomarker in biofluid using MS is its limited dynamic range of detection compared to a much wider range of protein concentrations in the samples13. Efforts have been made to simplify blood plasma samples by using affinity separations to enrich a sub-proteome with a common structural feature. For example, lectin affinity chromatography has been used to enrich the glycoproteins, which constitute one of the major subproteomes of blood 14–16. Functionally, the oligosaccharide moieties of various glycoproteins act as selectivity determinants, playing a fundamental role in many biological processes such as immune response and cellular regulation because cell-to-cell interactions involve sugar-sugar or sugar-protein specific recognition17. Embryonic development and cellular activation in vertebrates are typically accompanied by changes in cellular glycosylation profiles. Thus, it is not surprising that glycosylation changes are also a universal feature of malignant transformation and tumor progression. For this reason, glycoproteomics and glycomics approaches have found increasing applications in cancer biomarker research18. In fact, many clinically relevant cancer biomarkers are glycoproteins, including Her2/neu (breast cancer), prostate-specific antigen (PSA, prostate cancer) and CA 125 (ovarian cancer)19. In addition to cancer, several studies have suggested that aberrant glycosylation changes occur in neurodegenerative disorders. Liu et al have shown that aberrant glycosylation may modulate the tau protein at a substrate level, stabilizing its phosphorylated isoforms from brains in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients20. Reelin, a glycoprotein that is essential for the correct cytosolic organization of the central nervous system, is up-regulated in the brain and CSF in several neurodegenerative diseases, including frontotemporal dementia, progressive supranuclear palsy, Parkinson’s disease (PD) as well as AD 21. Furthermore, it is found that compared to PrPC, a glycoprotein with two conserved glycosylation sites, PrPSc has decreased level of bisecting GlcNAc and increased level of tri- and tetraantennary glycans, which indicated a decrease in the activity of an enzyme called N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase III 22. This possible perturbation to the glycosylation machinery of the cells that express prion proteins might cause changes in other glycosylation events, and lead to glycoprotein profile changes. Therefore, in-depth information extracted from the glycoproteome is useful for understanding the pathogenesis and facilitating diagnosis of prion diseases.

This study shows the utility of glycoprotein enrichment in biomarker discovery for prion disease, enabling the isolation, identification and relative quantification of glycoproteins from blood samples using lectin affinity enrichment, multidimensional separation and tandem mass spectrometry. More than seven hundred proteins were characterized with their relative abundances quantified in mouse plasma. Many of the identified proteins are known to be present at very low abundance, which demonstrates the utility of the approach for revealing low-abundance disease biomarkers. Isotopic labeling and spectral counting quantitation techniques showed strong correlation with each other. A panel of proteins exhibited significant changes in relative abundances at various time points of inoculation, suggesting that the enrichment of glycoprotein sub-proteomes prior to MS analysis may allow for the identification of prion disease biomarkers.

Materials and Methods

Sample Preparation

C57/Bl6 mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with 50 μL of 10% brain homogenate derived from mice clinically affected with RML prions or control unaffected mice. At 108, 158 and 198 days post inoculation (dpi), animals were anaesthetized with isoflorane and blood was collected by cardiac puncture into EDTA treated vacutainer tubes. The whole blood was centrifuged at 1000×g for 5 minutes. Plasma was decanted and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen for future use.

Materials

Tris hydrochloride, N-acetyl-D-glucosamine, methyl-α-D-mannopyranoside, methyl-α-D-glucopyranoside, manganese chloride tetrahydrate, formaldehyde, deuterated formaldehyde and sodium cyanoborohydride were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Sodium chloride, calcium chloride, sodium acetate, urea were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Agarose bound Concanavalin A (Con A, 6mg lectin/mL gel) and Wheat Germ Agglutinin (WGA, 7mg lectin/mL gel) were purchased from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA). Dithiothreitol (DTT) and sequencing grade modified trypsin were purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). Iodoacetamide was obtained from MP Biomedicals (Solon, OH).

Lectin Affinity Chromatography

Lectin affinity columns were prepared by adding 400μL each of Con A and WGA slurry to empty Micro Bio-Spin columns (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Plasma samples from 7 infected and 7 control mice were separately pooled. 40μL pooled mouse plasma from each group was diluted 10 times with the binding buffer (20mM Tris, 0.15M NaCl, 1mM Ca2+, 1mM Mn2+, pH 7.4) and loaded onto the lectin affinity column. After shaking for 6 hours the un-retained proteins were discarded and the lectin beads were washed with 2.5mL binding buffer. The captured glycoproteins were eluted with 2mL elution buffer (10mM Tris, 0.075M NaCl, 0.25M N-acetyl-D-glucosamine, 0.17M methyl-α-D-mannopyranoside, and 0.17M methyl-α-D-glucopyranoside). The eluted fraction was concentrated by a 10kD Centricon Ultracel YM-10 filter (Millipore, Billerica, MA).

Gel Electrophoresis

Protein samples were separated with a NuPAGE 10% Bis-Tris Gel and the NuPAGE MOPS SDS buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at 200V for 50min. The manufacturer’s instructions were followed. The gel was then stained with SimplyBlue SafeStain (Invitrogen) for 1hr, and washed with water overnight to increase the band intensity.

Proteolysis

Concentrated samples were denatured with 6M urea in 0.2M sodium acetate buffer, pH 8 and reduced by incubating with 10mM DTT at 37°C for 1hr. The reduced proteins were alkylated for 1hr in darkness with 40mM iodoacetamide. The alkylation reaction was quenched by adding DTT to a final concentration of 50mM. The samples were diluted to a final concentration of 1M urea. Trypsin was added at a 50:1 protein to trypsin mass ratio, and the samples were incubated at 37°C overnight.

Isotopic Labeling

Sodium cyanoborohydride was added to the protein digest to the final concentration of 50mM. Samples were labeled with 0.2mM formaldehyde or 0.2mM deuterated-formaldehyde. The mixed peptides were vortexed, incubated at 37°C for 1hr. 2M NH4OH was added to quench the reaction and the mixture was immediately dried in Speedvac. The samples were reconstituted in H2O.

High-pH RP LC

Equal amounts of light and heavy-labeled samples were combined and injected onto a Rainin HPLC with a high pH-stable RP column (Phenomenex Gemini C18, 150 × 2.1mm, 3 micron) at a flow rate of 150μL/min. The peptides were eluted with a 40min gradient 5–45% buffer B (Buffer A: 100mM ammonium formate, pH 10; Buffer B: acetonitrile (ACN)). Fractions were collected every 3min for 60min. Collected fractions were dried by Speedvac and reconstituted in 20 μL of 0.1% formic acid. 2 μL of each of the 12 fractions containing peptides were subjected to LC-MS/MS.

LC-MS/MS

A nanoLC system (Eksigent, Dublin, CA) was used to deliver the sample to a trap column and the solvent gradient (Mobile phase A: 0.1% formic acid in H2O; Mobile phase B: 0.1% formic acid in ACN). Samples were flushed with mobile phase A at 5μL/min for 3min and loaded onto a self-packed column (Prosphere HP C18, 100 × 0.15mm, 3μ). The peptides were eluted via a 5%–40% B gradient in 90min into a nanoelectrospray ionization (nESI) LTQ linear ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron Corp, San Jose, CA). The LTQ mass spectrometer was operated in a data-dependent mode in which an initial MS scan recorded the mass range of m/z 500–2000, and then the six most abundant ions were automatically selected for collision-activated dissociation (CAD). The spray voltage was 3.0 kV. The normalized collision energy was set at 35% for MS/MS.

Imunoblotting

Mouse plasma was boiled in NuPAGE® LDS 4X Sample Buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and NuPAGE® Reducing Agent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 5 minutes. The proteins in mouse plasma were separated by NuPAGE® Novex 4–12% Bis-Tris Gel (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), transferred onto nitrocellulose (GE Healthcare, UK) or Immobilon P (Millipore, Billerica, MA) membranes and probed with antibodies against murine serum amyloid protein (SAP)23–25 or apolipoprotein E (ApoE) (ab40882 or ab20874 respectively, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) Goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP secondary antibodies were used with luminescent detection (sc-2004, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA or 170–6515, Bio-Rad Hercules, CA), ECL Plus (GE Healthcare, UK). An equal amount of sample was loaded onto each lane, and equal loading and transfer to nitrocellulose was confirmed by Ponceau S or Coomassie blue staining.

Deglycosylation of SAP

1μl of mouse plasma diluted in 8μl water was denatured by 1μl of 10X Glycoprotein Denaturing Buffer (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) at 100 °C for 10 minutes. After proteins were denatured, 2μl of 10XG7 Reaction Buffer (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA), 2μl of 10% NP40, and 1μl of PNGase F (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) were added. The volume of the reaction system was brought up to 20μl by adding water. The reaction mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 1 hour.

Data Analysis

Raw LTQ data were converted to dta files by Bioworks Browser 3.3 software (Thermo Electron Corp), and searched against the Uniprot/Swiss-Prot Mus musculus (mouse) protein database using SEQUEST algorithm. The following parameters were applied during the database search: 2 Dalton precursor mass error tolerance, 1 Dalton fragment mass error tolerance, static modifications of carbamidomethylation for all cysteine residues (+57 Da), dimethylation for the formaldehyde labeled sample (+28 Da) or deuterated-formaldehyde labeled (+32 Da) lysine and the N-terminus. One missed cleavage site of trypsin was allowed. The following filtering criteria were applied for the protein identification: Xcorr ≥ 1.8 (+1 charge), 2.5 (+2 charge) and 3.5 (+3 charge); ΔCn ≥ 0.1; SEQUEST search Protein Probability < 0.001. Protein identifications were validated by the Trans-Proteomics Pipeline (TPP, Institute for System Biology). The proteins were filtered with a probability of 80% or higher, so that the false positive rates were about 3% for all time points. The relative abundance of each protein was calculated by the XPRESS software embedded in the TPP platform by reconstructing the light and heavy elution profiles of the precursor ions and determining the elution areas of each peak26. Open Mass Spectrometry Search Algorithm (OMSSA) developed at the National Center for Biotechnology Information 27 was used to merge the dta files and search the peak list against the Swissprot Mus musculus (mouse) protein database. E-value of 0.005 was used to filter the peptides/proteins with higher confidence for relative quantitation by spectral counting. The search results were sorted and the spectral counts of each identified protein were summed by an Excel macro function written in house. Gene ontology analysis of the identified proteins was conducted by the Onto-Express program developed by the Intelligent Systems and Bioinformatics Laboratory28.

Results and Discussion

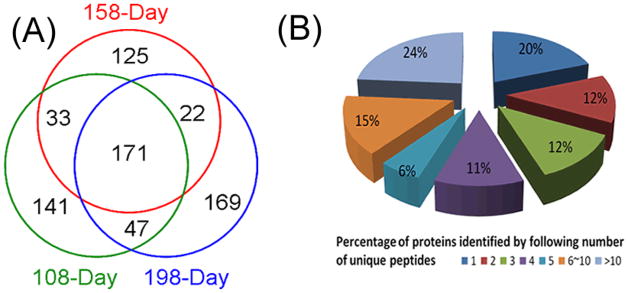

Proteomic analysis of plasma is very challenging due to the extreme dynamic range and complexity of proteins in this biofluid. By employing glycoprotein enrichment via lectin affinity chromatography and 2D RP-RPLC prior to tandem MS, we reduced sample complexity, dynamic range and improved separation of peptides. We identified 708 proteins from three time points of disease progression with a false discovery rate of 3% as determined by the ProteinProphet program. Each time point was analyzed in two replicate experiments. The complete list of identified proteins is shown in the Supplemental Information (Table S1). Figure 1A shows the Venn Diagrams of the numbers of proteins identified from all experiments. 171 proteins were commonly identified in all three time points, whereas 102 proteins were identified in two of the three time points. Among all the proteins identified, more than 80% of the proteins were identified by two or more unique peptides, indicating a comprehensive coverage of the glycoproteome in the blood plasma. 139 proteins (19.6%) were identified with single unique peptides (Figure 1B). We have chosen to include proteins identified with a single unique peptide, because they represent putative biomarkers with a low abundance in the blood proteome, a likely source of surrogate markers of disease. However, extra caution is needed for the validation of these proteins as potential candidate biomarkers.

Figure 1.

Number of proteins identified from all time points. (A) Venn diagram of the number of proteins identified at each time point after inoculation with 171 commonly identified in all three points; (B) Distribution of proteins identified by different numbers of unique peptides. More than 80% of total proteins were identified with multiple unique peptides.

Glycoprotein Enrichment by Lectin Affinity Chromatography

Direct analysis of complex proteomes such as blood plasma by conventional MS-based procedures is challenging because of the presence of very high-abundance proteins. For example, serum albumin is the single most abundant protein in blood, occupying 50% of the protein mass. Albumin’s tryptic peptides are over represented in the identified peptide list because the high abundance and large number of albumin tryptic peptides induce signal suppression of peptides from other proteins 29. Since albumin, along with several other abundant protein species in plasma, are nonglycosylated, they can be readily removed by negative adsorption on lectins, which have affinity to the glycans on glycoproteins 30. In this study, we utilized this “glyco-catch method,” by combining two lectins with broad selectivity on a single column, maximizing the coverage of the glycoproteome. Con A has a high affinity to high-mannose type N-glycans, whereas WGA is selective for N-acetyl-glucosamine (GlcNAc). The effectiveness of the removal of albumin and other abundant proteins via lectin affinity chromatography was confirmed by gel electrophoresis (data not shown). The lanes of the original plasma sample and the unbound fraction are dominated by just a few bands of proteins. The most dominant band is albumin, which is so abundant that other proteins close to it are obscured. Following glycoprotein enrichment, the elution fraction contains previously bound proteins showed a significant increase in the number of bands. These proteins spanned a wide molecular weight range, especially in the regions previously obscured by albumin. The effectiveness of glycoprotein enrichment can be further demonstrated by the database search results. With lectin selection, albumin no longer appears on the top of the list, although a moderate number of albumin peptides could still be detected, probably due to the non-specific and secondary binding events. We have further tested the combined use of immunodepletion, which removes the seven most abundant proteins in mouse plasma, before lectin affinity enrichment (Data not shown). Although this strategy works well for human blood samples, adding another dimension of depletion does not seem to be very beneficial for mouse blood samples, as the glycoproteins that dominate the MS/MS events such as α-2-macroglobulin and complement C3 precursor, are not removed using commercial mouse blood immunodepletion kits. In addition, by performing immunodepletion one risks losing important low abundance proteins that interact with the seven most abundant proteins.

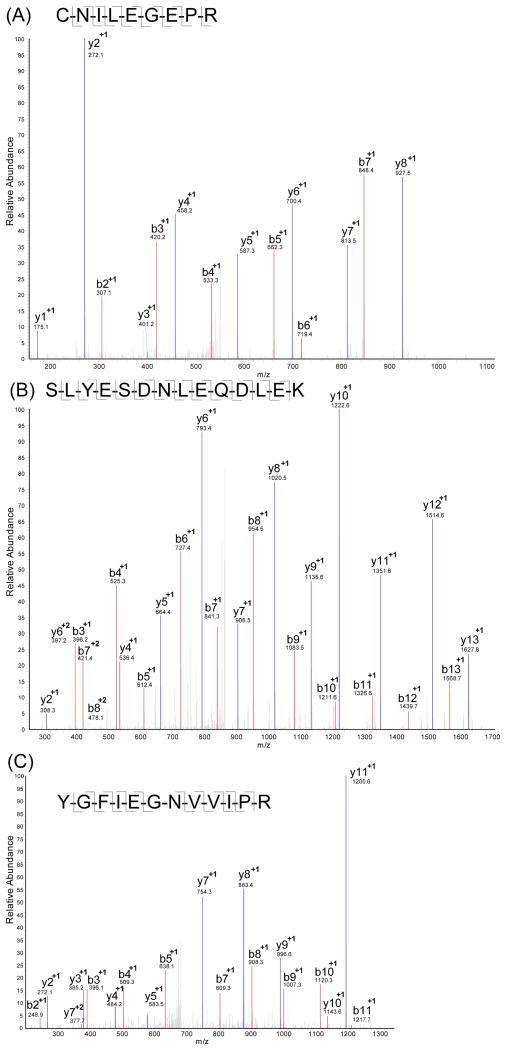

Many of the 708 proteins identified are known glycoproteins present at low abundance in blood. For example, Figure 2A shows a representative example of MS/MS detection and identification of a tryptic peptide from the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), a protein with a reported plasma abundance as low as 400 ng/mL 31. EGFR is a known transmembrane glycoprotein with 3 known glycosylation sites and 7 potential glycosylation sites. Figure 2B shows a tryptic peptide from angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), another glycoprotein that is reported to be present in human plasma at about 453.7±159.8 ng/mL 32. Both EGFR and ACE were identified with multiple distinct peptides. It is commonly observed that most false protein identifications tend to be the ones identified by a single peptide and many proteomic studies routinely discard single peptide identifications to reduce the false discovery rate. Since many glycoproteins exist at very low concentrations and glycopeptides are usually too large to be in the effective detection range of MS, it is likely that glycoproteins would only be identified by a single peptide. The removal of these protein identifications significantly increases the false-negative rate and reduces the overall sensitivity of the analysis. Therefore, single peptide hits were retained in our study as long as they met the probability cutoff from the ProteinProphet. For example, CD44, an integral cell membrane glycoprotein with reported human serum concentration as low as 81ng/mL and known correlation with invasion and metastasis in certain types of human carcinoma33, was detected with a single unique peptide in our study (Figure 2C). This single peptide was reproducibly identified in both light- and heavy-formaldehyde labeled samples.

Figure 2.

Tandem mass spectra of tryptic peptides from representative low-abundance glycoproteins identified in the global glycoproteomic analysis of serum samples. (A) Tryptic peptide CNILEGEPR from epidermal growth factor receptor; (B) Tryptic peptide SLYESDNLEQDLEK from angiotensin-converting enzyme; (C) The single tryptic peptide YGFIEGNVVIPR identified from CD44.

Although studies demonstrating the transmission of prion diseases by blood transfusion have suggested that prion proteins are present in the blood of afflicted animals and people 34, they were not detected in our study, most likely due to their extremely low abundance. Efforts are being made to develop more sensitive antibody-based methods to detect disease-associated prion aggregate in the blood as an alternative to the traditional postmortem test in the brain 35. Because prion protein is glycosylated 36, our glycoprotein enrichment protocol has the potential to detect it if increased sensitivity could be achieved by the use of optimized separation and MS detection.

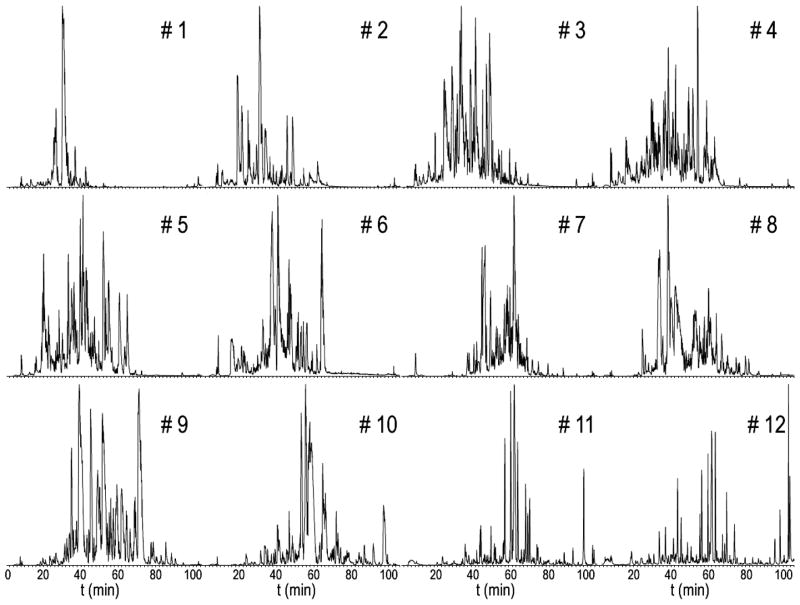

High-pH RPLC

Multidimensional separations have been employed in proteomics studies to reduce the complexity of the samples 37. Instead of using the popular strong cation exchange chromatography (SCX) as the first dimension, we used RPLC in both dimensions of separation under dramatically different pH conditions. Our lab has successfully adopted this scheme to enhance rat neuropeptide detection 38. The first and second dimensions exhibit great orthogonality in peptide separations due to charge changes in acidic and basic amino acid side chains under different pH conditions. Under high pH condition, the basic amino acids are neutral while the acidic ones are in negative charge state. In contrast, at low pH condition, the acidic amino acids remain neutral and the basic amino acids turn positively charged. Using RP as the first dimension bears several advantages: (i) high resolution permits collections of fractions with minimal overlap; (ii) higher recovery of peptides compared to SCX; (iii) the use of salt is minimal 39. The effectiveness of peptide separation by this method is demonstrated in Figure 3. Although there is a slight migration of elution time profiles, as the peptides eluting earlier in the first RPLC dimension tend to elute earlier in the second dimension as well, the widespread of peaks in all 12 fractions in the second dimension provides great resolution to enhance the proteomic detection. The co-elution of light- and heavy-labeled peptide pairs has also been achieved by this 2D RP-RP method.

Figure 3.

Chromatograms of the 2nd dimension of reversed-phase (RP)-HPLC separation. Each of the 12 fractions was obtained from 3 min collection of the 1st dimension of high-pH RP-HPLC separation. Great orthogonality was achieved between the two dimensions.

Assessment of Reproducibility of Relative Quantitation

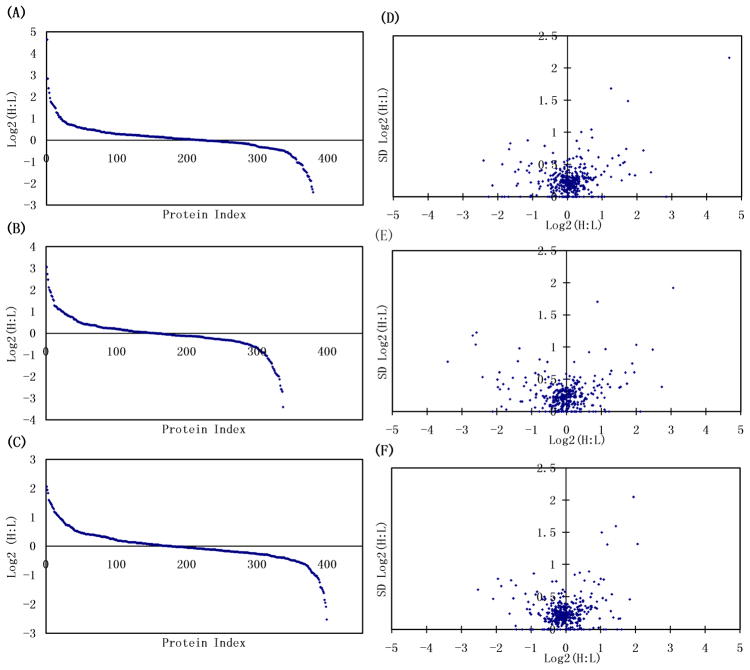

The isotopic labeling technique we used in this study is based on the reductive dimethylation of peptide primary amine groups (lysine or N-terminus) with formaldehyde and deuterated formaldehyde in the presence of reducing agent such as cyanoborohydride 40. A mass difference of 4 Da is produced for each labeling pair. The reaction is fast, easy to perform, and has been shown to be quantitative and free of detectable by-products40. At the peptide level, as expected, the distribution of all the isotopic-labeled peptide ratios exhibits a Gaussian profile, with the mean ratio of all the quantified tryptic peptides close to 1 (0.96), with a small standard deviation (SD) of 0.14, suggesting that the majority of the blood plasma glycoproteins remained unchanged despite different pathophysiological conditions. The ProteinProphet program integrates the quantitative information calculated from the spectra and the mean values of the ratios plus standard deviations are calculated for each protein expression value when multiple peptide measurements are available. Even though a large variation of relative quantitative ratios was observed at the peptide level, run-to-run variation between the replicate experiments at the protein level was well-controlled because the contribution from multiple peptides to the quantitation significantly lowers the effect of individual variation. Likewise proteins identified by a single peptide peak need to be interpreted with caution as their quantitation is highly variable.

Figure 4A–C illustrates the distribution of the heavy-to-light ratios in log2 scale for individual time points at the protein level. Threshold levels for significantly up- or down-regulated proteins are set to be 2-fold (+/−1 in log2 scale). The log2 ratio values of 86–91% of the proteins identified from individual time points fall between −1 and +1. Figure 4D–F displays the distribution of SD for the protein ratios detected at each time point. Overall, the mean SD of protein ratios is 0.26. The 171 proteins commonly identified at all of the time points displayed even lower variance, as these are among the most abundant proteins producing multiple unique peptides with high intensities. Overall, 90.5% of all the quantified proteins had a SD less than 0.5, a reasonably good measure of quantitative reproducibility in quantitative proteomic experiments for plasma biomarker discovery, taking into account of the underlying variation due to the multiple experimental steps 41. A caveat to keep in mind when generating a panel of biomarker candidates from the proteins with large ratio changes is that those proteins tend to have relatively higher SD. Therefore one should conservatively interpret those displaying a higher SD and manually verify the quality and validity of the quantitative data.

Figure 4.

The log2 ratios between infected (Heavy) and control samples (Light) at each time points (A: 108dpi; B: 158dpi; C: 198dpi) and the distribution of the standard deviations for each ratio (D: 108dpi; E: 158dpi; F: 198dpi). The standard deviations are calculated from the ratios of the peptides contributing to each individual protein.

In order to assess the validity of our quantitation study by isotopic labeling, we employed spectral counting to cross-check the protein ratios on the dataset collected at 158dpi. Spectral counting is based on the hypothesis that the MS/MS sampling rate of a particular protein, i.e. the number of tryptic peptides from a protein selected for collision induced dissociation (CID) in a large data set, is directly related to the abundance of the parent protein. Zybailov et al. recently compared quantitative MudPIT (multidimensional protein identification technology) results using spectral counting and stable isotope peak intensity to calculate protein expression ratios and demonstrated strong positive correlation between the two approaches 42. Consistent with the work of Zybailov et al., the quantitation results we observed from spectral counting positively correlated with those from extracted ion chromatograms of isotopically labeled peptide pairs. For example, in our study haptoglobin precursor was elevated more than 3-fold in the light form (SCLight: SCHeavy = 3.2), as determined by the spectral counting approach. A representative tryptic peptide LKYVMLPVADQDK was shown to have a XICLight: XICHeavy = 3.8 ratio from the extracted ion chromatograms of isotopic labeled pairs. Similarly, for hemoglobin (Hb) alpha chain, it is calculated that SCLight: SCHeavy = 3.8, which strongly correlates with the isotopic labeling result that XICLight: XICHeavy = 3.8 for the tryptic peptide TYFPHFDVSHGSAQVK. Interestingly, both haptoglobin and Hb are acute response proteins and it is well-known that the complex of haptoglobin and Hb is elevated in sera in response to inflammation43. Note that Hb protein is not glycosylated and it is likely that it has survived the lectin selection process by the formation of a complex with the glycoprotein haptoglobin. The calculation of the extracted ion chromatogramss were performed by the PepQuan function of Bioworks software. Calculations of haptoglobin and hemoglobin by the XPRESS based algorithm, however, identified a 2.4 and 1.9 fold up-regulation respectively in the 158dpi samples, indicating that the XPRESS algorithm generates more conservative quantitation results than could be obtained directly from extracted ion chromatograms. This conservation makes those proteins exceeding the 2-fold threshold more likely to have dramatic changes in the diseased conditions. Overall, the two quantitation techniques, quantifying extracted chromatograms and spectral counting, positively correlate with each other and provide complementary means to cross validate quantitative results. Although spectral counting is convenient, free from isotope labeling procedures and is reported to provide a greater dynamic range of quantitation compared with stable isotopic labeling strategies, the results can be unreliable for proteins at low abundance since only a small number of peptide identifications are used for quantitation. On a number of occasions we have observed that the results obtained from isotopic labeling outperformed those from spectral counting for proteins with low counts. For peptides identified with both isotopic forms, extracted ion chromatograms gave better accuracy in measuring the relative quantity. Since potential biomarkers are likely to be proteins with low abundance and quantitation accuracy and reproducibility are key factors, we utilized the isotope labeling approach for quantitation.

The consistency of glycoprotein enrichment across different samples, which is important for accurate quantitation of potential biomarkers, has been demonstrated in our previous work by spiking chicken ovalbumin into mouse plasma as an internal standard 44. All the tryptic peptides identified from the spiked ovalbumin were averaged to give a 1.1:1 ratio for isotopically-labeled pairs, a 10% error for such a multi-step procedure.

Among the 708 total proteins identified at all three time points, 53 proteins (7.5%) were increased more than two-fold in one or more time points, whereas 58 proteins (8.2%) had more than a 2-fold decrease. The lists of these two groups are illustrated in Table 1. It is not surprising that the majority of proteins exhibiting large fold changes are not shared amongst the three time points, as many differentially-regulated proteins are at very low abundances, which are not detected in great reproducibility due to the inherent limits of this methodology originating from the multi-step sample processing, the dynamic range of detection and the random precursor selection in the MS/MS analysis.

Table 1.

The list of significantly up- and down-regulated proteins at each time point. Infected samples were labeled in the heavy form (H) whereas control samples were labeled with light form (L).

| Time Points (Up) | Accession | NXS/T, Glycosylation sites* | Description | Protein Probability | Sequence Coverage % | H:L | Log2 (H:L) | Log2(H:L) std** | Unique Peptides | Spectral Counts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 108 DPI | Q61830 | 8, 7 | Macrophage mannose receptor | 1.00 | 1.7 | 25.00 | 4.64 | 2.16 | 2 | 2 |

| Q62073 | 8, 0 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 7 | 0.92 | 2.4 | 7.14 | 2.84 | 0.00 | 1 | 4 | |

| Q9JIE3 | 0, 0 | Otoraplin | 0.95 | 17.2 | 5.26 | 2.40 | 0.38 | 1 | 4 | |

| Q91VY5 | 1, 0 | JmjC domain-containing histone demethylation protein 3B | 0.90 | 0.9 | 4.55 | 2.18 | 0.72 | 2 | 4 | |

| Q4QRL3 | 2, 0 | Coiled-coil domain-containing protein 88B | 0.81 | 2.1 | 3.85 | 1.94 | 0.33 | 3 | 15 | |

| P12246 | 1, 1 | Serum amyloid P-component | 1.00 | 25.4 | 3.45 | 1.79 | 0.35 | 7 | 21 | |

| P08226 | 0, 0 | Apolipoprotein E | 1.00 | 50.2 | 3.33 | 1.74 | 1.49 | 26 | 80 | |

| Q80XJ3 | 5, 0 | Tetratricopeptide repeat protein 28 | 0.95 | 8 | 3.23 | 1.69 | 0.74 | 6 | 9 | |

| Q60994 | 2, 0 | Adiponectin | 1.00 | 4 | 3.13 | 1.64 | 0.54 | 2 | 9 | |

| Q99NI3 | 6, 0 | General transcription factor II-I repeat domain-containing protein 2 | 0.97 | 6.2 | 3.03 | 1.60 | 0.52 | 3 | 4 | |

| P04945 | 0, 0 | Ig kappa chain V-VI region NQ2-6.1 | 1.00 | 14.8 | 2.94 | 1.56 | 0.25 | 2 | 17 | |

| Q80ZE5 | 0, 0 | Membrane progestin receptor beta | 0.97 | 5.6 | 2.86 | 1.51 | 0.49 | 1 | 17 | |

| Q61646 | 4, 4 | Haptoglobin | 1.00 | 60.2 | 2.78 | 1.47 | 0.64 | 57 | 791 | |

| P01942 | 0, 0 | Hemoglobin subunit alpha | 1.00 | 43 | 2.44 | 1.29 | 0.60 | 14 | 303 | |

| Q9QZS0 | 2, 2 | Collagen alpha-3(IV) chain | 0.94 | 7.9 | 2.38 | 1.25 | 1.68 | 4 | 11 | |

| Q9Z265 | 3, 0 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase Chk2 | 0.90 | 6.4 | 2.38 | 1.25 | 0.31 | 2 | 3 | |

| P02088 | 0, 0 | Hemoglobin subunit beta-1 | 1.00 | 67.3 | 2.22 | 1.15 | 0.48 | 19 | 103 | |

| P01654 | 0, 0 | Ig kappa chain V-III region PC 2880/PC 1229 | 1.00 | 53.2 | 2.08 | 1.06 | 0.00 | 4 | 12 | |

| Q9WUU7 | 2, 2 | Cathepsin Z | 0.94 | 3.9 | 2.08 | 1.06 | 0.00 | 1 | 1 | |

| Q7TMY8 | 24, 0 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase HUWE1 | 0.88 | 3.8 | 2.08 | 1.06 | 0.39 | 1 | 5 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| 158 DPI | P08226 | 0, 0 | Apolipoprotein E | 1.00 | 15.4 | 8.33 | 3.06 | 1.92 | 5 | 10 |

| Q9D2N9 | 1, 0 | Vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 33A | 1.00 | 9.4 | 6.67 | 2.74 | 0.38 | 3 | 7 | |

| A2AAJ9 | 8, 0 | Obscurin | 0.88 | 2.4 | 5.56 | 2.47 | 0.96 | 2 | 13 | |

| Q8BH74 | 4, 0 | Nuclear pore complex protein Nup107 | 0.98 | 6.8 | 4.35 | 2.12 | 0.00 | 2 | 14 | |

| P11680 | 2, 1 | Properdin | 1.00 | 4.7 | 4.00 | 2.00 | 1.04 | 2 | 6 | |

| Q9CXA2 | 2, 0 | Probable proline racemase | 0.86 | 9.9 | 3.85 | 1.94 | 0.61 | 1 | 2 | |

| Q80YW5 | 0, 0 | B box and SPRY domain-containing protein | 0.82 | 1.9 | 3.70 | 1.89 | 0.75 | 1 | 2 | |

| Q06335 | 1, 1 | Amyloid-like protein 2 | 0.99 | 6.6 | 3.33 | 1.74 | 0.43 | 2 | 7 | |

| P02468 | 14, 14 | Laminin subunit gamma-1 | 0.81 | 5.5 | 3.23 | 1.69 | 0.60 | 5 | 18 | |

| Q9WTL8 | 3, 0 | Aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator-like protein 1 | 0.83 | 5.1 | 2.94 | 1.56 | 0.38 | 1 | 11 | |

| P11378 | 0, 0 | Nuclear transition protein 2 | 0.95 | 17.9 | 2.86 | 1.51 | 0.37 | 1 | 6 | |

| Q9JKK8 | 11, 0 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase ATR | 0.99 | 5.2 | 2.44 | 1.29 | 0.63 | 2 | 29 | |

| O35664 | 10, 8 | Interferon-alpha/beta receptor beta chain | 1.00 | 5.3 | 2.38 | 1.25 | 0.58 | 4 | 12 | |

| Q61646 | 4, 4 | Haptoglobin | 1.00 | 55.6 | 2.38 | 1.25 | 0.38 | 48 | 422 | |

| Q8K4L3 | 12, 0 | Supervillin | 0.96 | 3.9 | 2.33 | 1.22 | 0.00 | 3 | 35 | |

| Q5SQM0 | 8, 0 | Echinoderm microtubule-associated protein-like 5-like | 0.90 | 1.6 | 2.27 | 1.18 | 0.43 | 3 | 15 | |

| Q62073 | 8, 0 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 7 | 1.00 | 5.2 | 2.17 | 1.12 | 0.97 | 2 | 10 | |

| P05208 | 0, 0 | Elastase-2A | 0.97 | 5.2 | 2.17 | 1.12 | 0.00 | 1 | 1 | |

| Q9QXE0 | 1, 0 | 2-hydroxyacyl-CoA lyase 1 | 0.84 | 11.2 | 2.17 | 1.12 | 0.00 | 2 | 2 | |

| P01654 | 0, 0 | Ig kappa chain V-III region PC 2880/PC 1229 | 1.00 | 30.6 | 2.13 | 1.09 | 0.03 | 2 | 6 | |

| Q91Z46 | 4, 0 | Dual specificity protein phosphatase 7 | 0.99 | 7.9 | 2.13 | 1.09 | 0.21 | 2 | 12 | |

| Q8BGC4 | 2, 0 | Zinc-binding alcohol dehydrogenase domain-containing protein 2 | 0.98 | 9.5 | 2.04 | 1.03 | 0.50 | 2 | 14 | |

| P01680 | 0, 0 | Ig kappa chain V-IV region S107B | 1.00 | 8.5 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 0.37 | 2 | 5 | |

| P02088 | 0, 0 | Hemoglobin subunit beta-1 | 1.00 | 58.5 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 0.29 | 20 | 227 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| 198 DPI | Q7TNF8 | 2, 0 | Peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor-associated protein 1 | 0.87 | 1.4 | 4.17 | 2.06 | 1.32 | 1 | 7 |

| O35464 | 10, 6 | Semaphorin-6A | 0.96 | 6.9 | 3.85 | 1.94 | 2.05 | 3 | 3 | |

| Q9WUU7 | 2, 2 | Cathepsin Z | 0.99 | 12.4 | 3.57 | 1.84 | 0.46 | 1 | 2 | |

| Q6QI06 | 10, 0 | Rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR | 1.00 | 3.8 | 3.03 | 1.60 | 0.00 | 4 | 4 | |

| Q810F8 | 1, 0 | T-box transcription factor TBX10 | 1.00 | 6 | 2.94 | 1.56 | 0.17 | 3 | 10 | |

| P02104 | 0, 0 | Hemoglobin subunit epsilon-Y2 | 1.00 | 12.9 | 2.86 | 1.51 | 0.16 | 2 | 7 | |

| P70695 | 1, 0 | Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase isozyme 2 | 1.00 | 16.2 | 2.78 | 1.47 | 0.00 | 3 | 3 | |

| P08226 | 0, 0 | Apolipoprotein E | 1.00 | 37.3 | 2.70 | 1.43 | 1.60 | 14 | 54 | |

| Q02780 | 2, 0 | Nuclear factor 1 A-type | 0.92 | 2.4 | 2.56 | 1.36 | 0.18 | 1 | 4 | |

| Q78J03 | 0, 0 | Methionine-R-sulfoxide reductase B2, mitochondrial | 1.00 | 8.6 | 2.50 | 1.32 | 0.54 | 2 | 52 | |

| Q9CWR2 | 3, 0 | SET and MYND domain-containing protein 3 | 0.88 | 2.3 | 2.44 | 1.29 | 0.28 | 1 | 10 | |

| Q4U4S6 | 28, 0 | Xin actin-binding repeat-containing protein 2 | 1.00 | 3.8 | 2.27 | 1.18 | 1.31 | 7 | 9 | |

| P04945 | 0, 0 | Ig kappa chain V-VI region NQ2-6.1 | 1.00 | 31.5 | 2.22 | 1.15 | 0.45 | 3 | 27 | |

| P0C090 | 6, 0 | Ring finger and CCCH-type zinc finger domain-containing protein 2 | 0.98 | 2.8 | 2.22 | 1.15 | 0.00 | 2 | 24 | |

| P09470 | 15, 13 | Angiotensin-converting enzyme, somatic isoform | 0.99 | 4.3 | 2.13 | 1.09 | 0.77 | 2 | 4 | |

| Q8BZM1 | 5, 0 | Glomulin | 0.94 | 7 | 2.13 | 1.09 | 0.00 | 4 | 10 | |

| O70165 | 1, 1 | Ficolin-1 | 1.00 | 13.5 | 2.08 | 1.06 | 0.48 | 4 | 6 | |

| A2AWL7 | 21, 0 | MAX gene-associated protein | 0.95 | 5 | 2.04 | 1.03 | 1.50 | 3 | 3 | |

| Q811D2 | 15, 0 | Ankyrin repeat domain-containing protein 26 | 1.00 | 3.6 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 0.78 | 3 | 80 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Time Points (Down) | Accession | NXS/T, Glycosylation sites | Description | Protein Probability | Sequence Coverage % | H:L | Log2 (H:L) | Log2(H:L) std | Unique Peptides | Spectral Counts |

|

| ||||||||||

| 108 DPI | Q5H8C4 | 27, 0 | Vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 13A | 0.94 | 3.2 | 0.49 | −1.03 | 0.52 | 2 | 4 |

| Q6JPI3 | 7, 0 | Mediator of RNA polymerase II transcription subunit 13-like | 0.90 | 2.7 | 0.49 | −1.04 | 0.02 | 2 | 2 | |

| O08604 | 5, 5 | Retinoic acid early-inducible protein 1-gamma | 0.80 | 10.4 | 0.49 | −1.04 | 0.00 | 1 | 2 | |

| Q80U16 | 9, 0 | Protein FAM65B | 0.92 | 2.6 | 0.48 | −1.05 | 0.22 | 2 | 16 | |

| P63034 | 4, 0 | Cytohesin-2 | 0.99 | 8 | 0.48 | −1.07 | 0.00 | 2 | 9 | |

| Q3UMC0 | 3, 0 | Spermatogenesis-associated protein 5 | 0.88 | 10.5 | 0.47 | −1.10 | 0.38 | 1 | 1 | |

| P28666 | 9, 8 | Murinoglobulin-2 | 1.00 | 31 | 0.47 | −1.10 | 0.48 | 36 | 266 | |

| Q9ERU9 | 22, 0 | E3 SUMO-protein ligase RanBP2 | 0.98 | 2.1 | 0.45 | −1.14 | 0.88 | 5 | 17 | |

| P35585 | 0, 0 | AP-1 complex subunit mu-1 | 0.90 | 3.1 | 0.45 | −1.16 | 0.41 | 1 | 2 | |

| Q71KU9 | 1, 0 | Fibrinogen-like protein 1 | 0.97 | 9.6 | 0.40 | −1.34 | 0.54 | 1 | 1 | |

| Q61699 | 6, 0 | Heat shock protein 105 kDa | 1.00 | 4.2 | 0.39 | −1.36 | 0.00 | 4 | 4 | |

| Q5DU37 | 8, 0 | Zinc finger FYVE domain-containing protein 26 | 1.00 | 3.2 | 0.38 | −1.41 | 0.42 | 2 | 9 | |

| P02089 | 0, 0 | Hemoglobin subunit beta-2 | 1.00 | 45.6 | 0.37 | −1.42 | 0.20 | 3 | 6 | |

| P04940 | 0, 0 | Ig kappa chain V-VI region NQ2-17.4.1 | 1.00 | 35.5 | 0.36 | −1.46 | 0.17 | 3 | 14 | |

| Q9QY06 | 7, 0 | Myosin-Ixb | 0.85 | 3.7 | 0.35 | −1.50 | 0.39 | 2 | 2 | |

| P17047 | 17, 16 | Lysosome-associated membrane glycoprotein 2 | 0.96 | 2.4 | 0.32 | −1.64 | 0.83 | 1 | 3 | |

| Q91XQ0 | 22, 0 | Dynein heavy chain 8, axonemal | 0.90 | 2.8 | 0.31 | −1.68 | 0.74 | 3 | 5 | |

| Q6PIE5 | 5, 0 | Sodium/potassium-transporting ATPase subunit alpha-2 | 0.90 | 2.6 | 0.31 | −1.69 | 0.00 | 3 | 5 | |

| P01658 | 0, 0 | Ig kappa chain V-III region MOPC 321 | 0.93 | 22 | 0.29 | −1.81 | 0.00 | 1 | 1 | |

| P63087 | 1, 0 | Serine/threonine-protein phosphatase PP1-gamma catalytic subunit | 0.96 | 3.7 | 0.27 | −1.87 | 0.50 | 1 | 10 | |

| P70336 | 6, 0 | Rho-associated protein kinase 2 | 0.83 | 4.3 | 0.27 | −1.88 | 0.00 | 2 | 2 | |

| Q5S006 | 12, 0 | Leucine-rich repeat serine/threonine-protein kinase 2 | 0.94 | 0.8 | 0.22 | −2.15 | 0.17 | 2 | 7 | |

| P29477 | 7, 0 | Nitric oxide synthase, inducible | 0.85 | 5.2 | 0.21 | −2.26 | 0.00 | 2 | 10 | |

| Q61602 | 18, 0 | Zinc finger protein GLI3 | 0.99 | 3 | 0.19 | −2.41 | 0.56 | 2 | 3 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| 158 DPI | P61922 | 2, 0 | 4-aminobutyrate aminotransferase, mitochondrial | 0.90 | 8.4 | 0.50 | −1.01 | 0.00 | 2 | 2 |

| Q9ER99 | 2, 0 | Regulatory solute carrier protein family 1 member 1 | 0.81 | 7 | 0.49 | −1.04 | 0.33 | 1 | 1 | |

| P13405 | 7, 0 | Retinoblastoma-associated protein | 0.87 | 5.1 | 0.48 | −1.05 | 0.17 | 1 | 3 | |

| P17047 | 17, 16 | Lysosome-associated membrane glycoprotein 2 | 1.00 | 6.5 | 0.45 | −1.16 | 0.45 | 3 | 7 | |

| Q6RHW0 | 2, 0 | Keratin, type I cytoskeletal 9 | 1.00 | 4.7 | 0.44 | −1.18 | 0.53 | 2 | 7 | |

| P70670 | 6, 0 | Nascent polypeptide-associated complex subunit alpha, muscle-specific form | 0.99 | 6.5 | 0.43 | −1.22 | 0.40 | 6 | 8 | |

| Q4VAH7 | 9, 4 | Ig-like domain-containing protein UNQ305/PRO346 homolog | 0.84 | 5.8 | 0.41 | −1.28 | 0.15 | 1 | 8 | |

| P02089 | 0, 0 | Hemoglobin subunit beta-2 | 0.99 | 56.5 | 0.40 | −1.32 | 0.16 | 1 | 6 | |

| Q8BML1 | 2, 0 | Protein MICAL-2 | 0.96 | 4 | 0.39 | −1.35 | 0.98 | 2 | 4 | |

| P12382 | 2, 0 | 6-phosphofructokinase, liver type | 0.82 | 5 | 0.38 | −1.40 | 0.78 | 1 | 10 | |

| Q9CWS0 | 1, 0 | N(G),N(G)-dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase 1 | 0.89 | 9.5 | 0.34 | −1.54 | 0.52 | 2 | 7 | |

| Q70KF4 | 15, 0 | Cardiomyopathy-associated protein 5 | 1.00 | 3.4 | 0.32 | −1.62 | 0.19 | 5 | 10 | |

| P06328 | 0, 0 | Ig heavy chain V region VH558 B4 | 0.98 | 26.5 | 0.32 | −1.66 | 0.35 | 2 | 6 | |

| Q60649 | 3, 0 | Caseinolytic peptidase B protein homolog | 0.89 | 5.2 | 0.30 | −1.73 | 0.03 | 3 | 4 | |

| Q8BPB5 | 1, 1 | EGF-containing fibulin-like extracellular matrix protein 1 | 0.93 | 5.9 | 0.28 | −1.82 | 0.42 | 1 | 1 | |

| P48760 | 4, 0 | Folylpolyglutamate synthase, mitochondrial | 0.93 | 1.7 | 0.27 | −1.87 | 0.08 | 2 | 4 | |

| P50446 | 4, 0 | Keratin, type II cytoskeletal 6A | 0.99 | 10.3 | 0.27 | −1.91 | 0.34 | 2 | 6 | |

| Q8CDM4 | 8, 0 | Coiled-coil domain-containing protein 73 | 0.87 | 4.2 | 0.26 | −1.92 | 0.61 | 1 | 1 | |

| Q8R1R4 | 2, 1 | Interleukin-34 | 0.98 | 6 | 0.26 | −1.97 | 0.38 | 2 | 75 | |

| P25206 | 1, 0 | DNA replication licensing factor MCM3 | 0.99 | 3.2 | 0.25 | −1.98 | 0.50 | 2 | 32 | |

| Q8VE95 | 1, 0 | UPF0598 protein | 0.92 | 8.3 | 0.23 | −2.12 | 0.00 | 1 | 1 | |

| Q5S006 | 12, 0 | Leucine-rich repeat serine/threonine-protein kinase 2 | 0.92 | 2.9 | 0.19 | −2.41 | 0.53 | 1 | 5 | |

| Q8BMG7 | 3, 0 | Rab3 GTPase-activating protein non-catalytic subunit | 0.87 | 4.9 | 0.17 | −2.58 | 1.23 | 3 | 3 | |

| Q8VCM3 | 0, 0 | Zinc finger FYVE domain-containing protein 21 | 0.96 | 7.3 | 0.16 | −2.61 | 1.04 | 1 | 1 | |

| P70662 | 6, 0 | LIM domain-binding protein 1 | 0.96 | 5.1 | 0.15 | −2.70 | 1.18 | 2 | 3 | |

| P08228 | 2, 0 | Superoxide dismutase [Cu-Zn] | 0.97 | 39.6 | 0.09 | −3.41 | 0.78 | 2 | 13 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| 198 DPI | P81105 | 3, 3 | Alpha-1-antitrypsin 1–6 | 1.00 | 52.7 | 0.50 | −1.00 | 0.23 | 2 | 17 |

| Q6NS57 | 7, 0 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase-binding protein 1 | 0.97 | 3.5 | 0.49 | −1.03 | 0.25 | 2 | 3 | |

| Q9DBB4 | 7, 0 | NMDA receptor-regulated 1-like protein | 0.90 | 6.7 | 0.49 | −1.03 | 0.00 | 2 | 2 | |

| P01878 | 4, 4 | Ig alpha chain C region | 1.00 | 23 | 0.49 | −1.04 | 0.31 | 8 | 40 | |

| Q8VI56 | 8, 7 | Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 4 | 0.99 | 6.8 | 0.47 | −1.08 | 0.42 | 5 | 7 | |

| P47878 | 3, 3 | Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 3 | 0.99 | 21.6 | 0.46 | −1.12 | 0.31 | 1 | 2 | |

| Q69ZW3 | 7, 0 | EH domain-binding protein 1 | 0.98 | 3.3 | 0.45 | −1.16 | 0.55 | 3 | 11 | |

| Q3TNU4 | 6, 0 | Putative uncharacterized protein ENSP00000382790 homolog | 0.96 | 4.1 | 0.42 | −1.26 | 0.00 | 1 | 1 | |

| Q9D306 | 4, 2 | Alpha-1,3-mannosyl-glycoprotein 4-beta-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase C | 0.97 | 2.5 | 0.37 | −1.42 | 0.00 | 2 | 2 | |

| Q5H8C4 | 27, 0 | Vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 13A | 0.93 | 6.5 | 0.37 | −1.43 | 0.68 | 5 | 10 | |

| Q99LB2 | 2, 0 | Dehydrogenase/reductase SDR family member 4 | 0.88 | 6.5 | 0.37 | −1.44 | 0.05 | 1 | 4 | |

| P59113 | 6, 0 | Fermitin family homolog 1 | 0.95 | 4 | 0.35 | −1.51 | 0.48 | 1 | 1 | |

| Q6PDQ2 | 5, 0 | Chromodomain-helicase-DNA-binding protein 4 | 0.96 | 5.3 | 0.34 | −1.57 | 0.76 | 2 | 6 | |

| P63087 | 1, 0 | Serine/threonine-protein phosphatase PP1-gamma catalytic subunit | 0.98 | 4 | 0.33 | −1.62 | 0.24 | 1 | 9 | |

| Q9DBG3 | 3, 0 | AP-2 complex subunit beta-1 | 0.92 | 2.5 | 0.28 | −1.86 | 0.66 | 4 | 14 | |

| Q60847 | 6, 5 | Collagen alpha-1(XII) chain | 1.00 | 1.8 | 0.26 | −1.95 | 0.78 | 3 | 5 | |

| Q8VC66 | 3, 0 | Afadin-and alpha-actinin-binding protein | 0.91 | 4.4 | 0.23 | −2.09 | 0.47 | 2 | 3 | |

| Q9WV91 | 8, 8 | Prostaglandin F2 receptor negative regulator | 0.94 | 12.3 | 0.17 | −2.53 | 0.61 | 1 | 22 | |

NXS/T is the number of consensus motif of N-glycosylation (X is any amino acid except for proline; the number of glycosylation sites is obtained from the annotation of Protein Knowledgebase (UniProtKB).

Log2(H:L) std is the standard deviation of protein quantitation in log2 scale.

Biological Significance

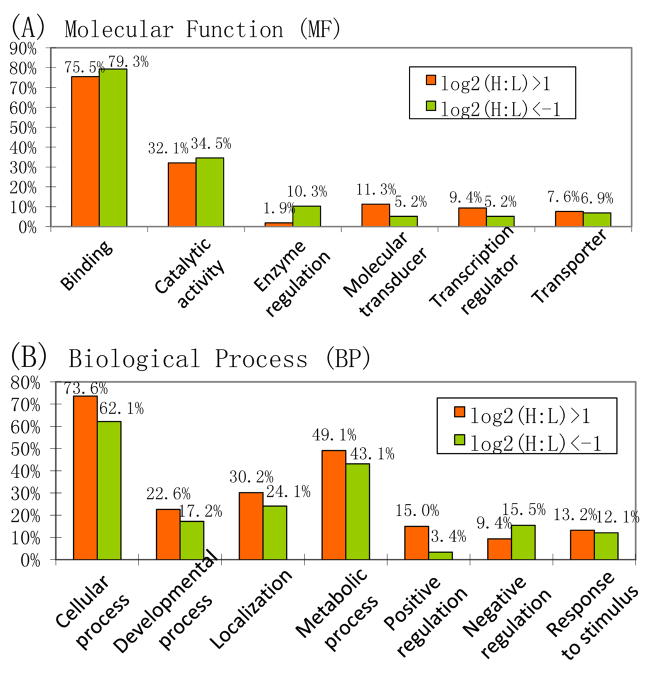

Gene ontology analysis of proteins listed in Table 1 revealed that more than 75% of the proteins with significant changes are involved in binding, which was in agreement with the percentage of all identified proteins that are related to binding (78.5%) (Figure 5). More than 30% from both groups have catalytic activities. About three quarters of the up-regulated proteins are involved in cellular processes, whereas the percentage of down-regulated proteins in this category is significantly lower. It is interesting to note that the proteins responsible for positive regulation of biological process are enriched in the up-regulated pool, whereas those responsible for negative regulation of biological process are enriched in the down-regulated pool. This suggests that certain biological processes are either enhanced or less inhibited with the onset of prion disease.

Figure 5.

Molecular function (MF) and biological process (BP) comparisons of the up- and down-regulated proteins. Gene ontology analysis was performed by Onto-Express (http://vortex.cs.wayne.edu/ontoexpress).

One up-regulated protein in prion infected samples that also positively regulates biological process is apolipoprotein E (ApoE). In this study, ApoE has been shown to be up-regulated constantly throughout all the three time points, with changes of 3.3, 8.3 and 2.7-fold, respectively. Although murine ApoE is not a known glycoprotein, the well-known hydrophobic binding property of Con A in addition to its lectin-glycan interaction45 may lead to the reproducible isolation of ApoE. Another possible mechanism of ApoE isolation is the formation of protein complex, similar to that of the aforementioned hemoglobin-haptoglobin complex.

ApoE is the major component of the very low density lipoproteins (VLDL), whose function is to remove excess cholesterol from the blood and transport it to the liver for processing. In the nervous system, non-neuronal cell types such as astroglia and microglia are the primary producers of ApoE, while neurons preferentially express the receptors for this protein. The role of ApoE in the nervous system is thought to be involved in nerve growth, regeneration and neuronal repair46. ApoE is associated with age-related risk for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and plays critical roles in Aβ homeostasis. Research has suggested that ApoE acts both within microglia and in the extracellular space to affect the clearance of Aβ through promoting its proteolysis. Importantly, the ApoE4 isoform exhibits an impaired ability to promote Aβ proteolysis, resulting in increased vulnerability to AD in individuals with that gene variation47. Several studies have reported the involvement of ApoE with TSE progression. Elevated ApoE concentrations have been reported in the brains of scrapie infected mice and has been detected in some prion protein aggregates48. Choe et al. have shown increased concentration of ApoE in the CSF of patients with vCJD as compared to sporadic CJD (sCJD)49. Despite the long-established relationship between ApoE and prion diseases, the sample sources of previous studies have been limited to brain and CSF, which are not as accessible compared to blood. The earliest time point of elevated ApoE concentration can be used as a useful diagnosis that has not been previously established. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first report on the elevated concentration of ApoE from blood plasma at different time points during prion disease onset and progression.

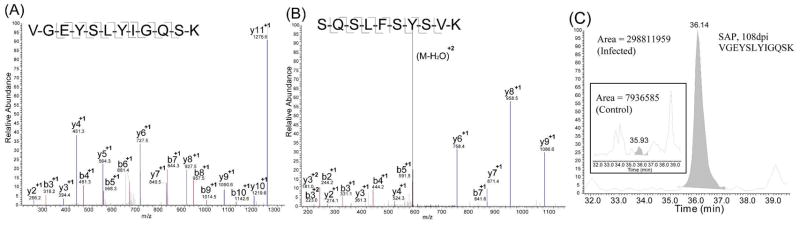

As discussed, the 171 proteins commonly found in all time points mainly represent those present at relatively higher abundance and thus may have a lower chance to be used as potential biomarkers of lower abundance. Therefore, it is of equal importance to look for significant changes in other parts of the Venn diagram. Among the significantly changed proteins that were only detected in two of the three time points, serum amyloid P-component (SAP) has drawn our attention. SAP was characterized by 7 unique peptides at 108 days and 4 peptides at 158 post inoculation (Table 1 & Table S1). Representative spectra for two peptides, VGEYSLYIGQSK and SQSLFSYSVK from 108 and 158dpi are shown in Figure 6. Overall, SAP was significantly elevated in the mass spectra of infected 108dpi samples by 3.4 fold (Table 1), but not in 158dpi samples (Table S1). SAP is a 204-residue secreted glycoprotein present at low abundance (30–45 μg/mL in plasma) with a single N-glycosylation site at position 51. SAP is associated in vivo with all types of amyloid deposits, and it is now believed that the tissue accumulation of SAP in various types of amyloids is due to its particular affinity for the amyloid molecules 50. SAP has also been found to co-localize with neurofibrillary pathology in various neurodegenerative diseases including AD, Creutzfedt-Jacob disease (CJD), PD, and diffuse Lewy body disorders 51–53. It is suggested that SAP may contribute to the failure of clearance of amyloid deposits in vivo, causing tissue damage and disease, which has made it a new therapeutic target to both systemic amyloidosis and diseases associated with local amyloid deposits including AD 54.

Figure 6.

Identification of serum amyloid P-component (SAP) protein as a putative biomarker in prion disease. (A) and (B): Representative tryptic peptides from SAP. (C): Extracted ion chromatograms of SAP peptides indicate elevated concentration in the infected samples.

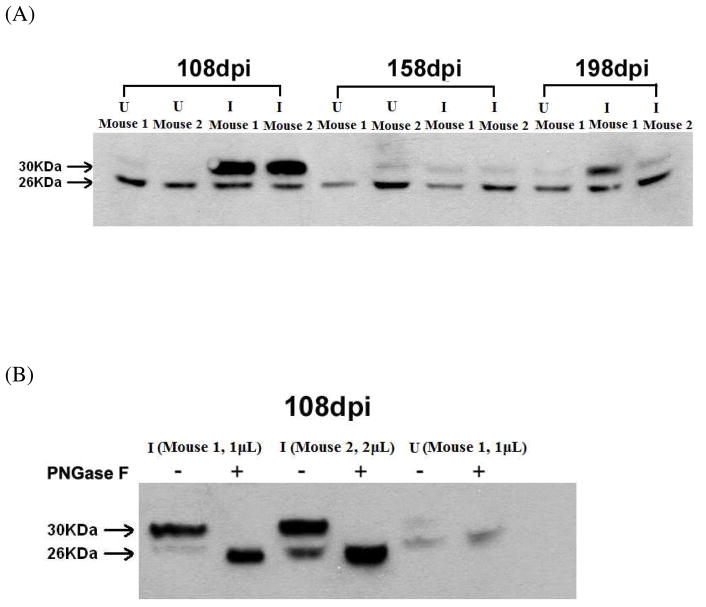

To validate our observation in quantitative MS experiments, Western blotting was performed using a well-established anti-SAP antibody23–25 with plasma samples from all three time points (Figure 7A). Interestingly, the Western blot experiments showed two bands at 26 kDa and 30 kDa, respectively. The intensity of the 26 kDa band remains relatively constant regardless of the physiological status, whereas the level of the heavy band was significantly elevated from the infected sample at 108dpi. Previously, using mink, Husby and coworkers identified for the first time the non-glycosylated SAP from a mammalian species 55. Therefore we speculated that the two bands corresponded to the mono- and un-glycosylated forms, respectively. This was confirmed by deglycosylating the proteins using PNGase F digestion, which cleaves N-glycans. The molecular weight of the heavy band changed to its light counterpart after cleavage (Figure 7B), further supporting the band assignment. We conclude that the observed 3.4 fold elevation of SAP in the MS analysis was solely due to the increase in glycosylated SAP from infected samples at 108dpi due to the employment of lectin-affinity chromatography for glycoprotein enrichment, whereas the level of non-glycosylated isoform remained relatively stable. The glycosylated SAP returned to its normal level with the progression of the disease. The faint heavy bands at 198dpi attributed to the failure of MS detection of SAP at that time point. The reproduction of the glycoproteomic result for SAP using immunoblotting and PNGase F treatment strongly validates the lectin fractionation and subsequent MS-based quantitative proteomic approach. While the underlying mechanism leading to the elevation of the glycosylated form and its particular trend at different time points is unclear at this point, this study provides a basis for further investigation on SAP as a potential biomarker and its pathological role in the progression of prion disease.

Figure 7.

Validation of MS-based glycoproteomic approach using Western blotting analysis and enzymatic treatment. (A) Immunoblotting for serum amyloid P-component (SAP) protein. 2μL mouse plasma from control uninfected (U) and infected (I) groups on 108, 158 and 198 days post-inoculation (dpi) were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-SAP antibody. Two forms of SAP were detected. (B) Glycosylated SAP is up-regulated at 108 dpi in infected mice. 1μL or 2μL mouse plasma from both control uninfected (U) and infected (I) groups on 108dpi were treated by PNGase F or left untreated. The mouse plasma were then separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-SAP antibody. After PNGase F treatment, the band with molecular weight of 30 kDa shifted to 26 kDa, confirming that the glycosylated SAP is elevated in infected group.

Our finding that a number of proteins exhibited altered expression either qualitatively or quantitatively in the plasma samples collected from inoculated animals suggests a molecular link of these proteins with disease onset and progression. This MS-based global analysis of glycoproteins in plasma samples provides a new opportunity for quantitative examination of proteins from diseased samples and investigation of the pathological mechanisms underlying their changes in abundance.

Conclusions

In summary, we have successfully developed an analytical platform that can readily detect and quantify glycoproteins in complex biofluid samples to facilitate the biomarker discovery for prion diseases. By applying this platform 708 proteins were identified and relatively quantified. Spectral counting and isotopic labeling quantitation positively correlated with each other and was useful to cross-validate quantitation. A protein list was generated, which can serve as a reference for future prion disease biomarker investigation. Western blot validation was performed on Serum Amyloid Protein, suggesting its potential use as a biomarker for prion disease. Further quantitative validations of the proteins exhibiting significant changes, either using MS-based multiple reaction monitoring (MRM), or antibody based measurements, are likely to reveal more information on the correlation of these proteins to prion disease state. This comparative glycoproteomic methodology offers significant promise in the search for low-abundance, glycosylated disease biomarkers.

In the future, immuno-depletion of the most abundant proteins prior to lectin selection will be further explored. Different lectin combinations with various selectivities towards glycan structures can enrich for different profiles of the serum glycoproteome and provides more information on the changes of the glycoproteome with prion disease. Once a panel of proteins can be detected with reproducible changes by mass spectrometry, other methods such as antibody-based assays will be required for validation before the candidates could be useful in diagnostic assays.

Supplementary Material

The list of proteins identified at each time point (108, 158, and 198 dpi) showing the sequence coverage, unique peptides, spectral count, expression ratio and standard deviations. N/A indicates that the XPRESS function was unable to use a peptide profile to calculate the expression ratio.

The list of peptides identified at each time point and each replicate experiments. The lists of identifications include amino acid sequences, theoretical and observed precursor masses and confidence of identification.

Acknowledgments

We thank University of Wisconsin Human Proteomics Program for access to the LTQ instrument. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health through grant AI0272588 and the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. L.L. acknowledges an Alfred P. Sloan Research Fellowship. We thank Dr. Timothy Heath for writing the Excel macro function for spectral counting.

References

- 1.Borchelt DR, Scott M, Taraboulos A, Stahl N, Prusiner SB. Scrapie and Cellular Prion Proteins Differ in Their Kinetics of Synthesis and Topology in Cultured-Cells. J Cell Biol. 1990;110(3):743–752. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.3.743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caughey B, Race RE, Ernst D, Buchmeier MJ, Chesebro B. Prion Protein-Biosynthesis in Scrapie-Infected and Uninfected Neuro-Blastoma Cells. J Virol. 1989;63(1):175–181. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.1.175-181.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chesebro B, Race R, Wehrly K, Nishio J, Bloom M, Lechner D, Bergstrom S, Robbins K, Mayer L, Keith JM. Nature. 1985;315:331. doi: 10.1038/315331a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oesch B, Westaway D, Walchli M, McKinley MP, Kent SB, Aebersold R, Barry RA, Tempst P, Teplow DB, Hood LE. Cell. 1985;40:735. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90333-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schaller O, Fatzer R, Stack M, Clark J, Cooley W, Biffiger K, Egli S, Doherr M, Vandevelde M, Heim D, Oesch B, Moser M. Validation of a western immunoblotting procedure for bovine PrP(Sc) detection and its use as a rapid surveillance method for the diagnosis of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) Acta Neuropathologica. 1999;98:7. doi: 10.1007/s004010051106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burkhard PR, Sanchez JC, Landis T, Hochstrasser DF. Neurology. 2001;56:1528. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.11.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choe LH, Green A, Knight RS, Thompson EJ, Lee KH. Electrophoresis. 2002;23:2242. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200207)23:14<2242::AID-ELPS2242>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Otto M, Wiltfang J, Cepek L, Neumann M, Mollenhauer B, Steinacker P, Ciesielczyk B, Schulz-Schaeffer W, Kretzschmar HA, Poser S. Neurology. 2002;58:192. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.2.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parveen I, Moorby J, Allison G, Jackman R. Vet Res. 2005;36:665. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2005028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanchez JC, Guillaume E, Lescuyer P, Allard L, Carrette O, Scherl A, Burgess J, Corthals GL, Burkhard PR, Hochstrasser DF. Proteomics. 2004;4:2229. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Everbroeck B, Boons J, Cras P. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2005;107:355. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zerr I, Bodemer M, Otto M, Poser S, Windl O, Kretzschmar HA, Gefeller O, Weber T. Lancet. 1996;348:846. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)08077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rifai N, Gillette MA, Carr SA. Protein biomarker discovery and validation: the long and uncertain path to clinical utility. Nat Biotech. 2006;24(8):971–983. doi: 10.1038/nbt1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Madera M, Mechref Y, Klouckova I, Novotny MV. High-sensitivity profiling of glycoproteins from human blood serum through multiple-lectin affinity chromatography and liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B. 2007;845(1):121–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.07.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang Z, Harris LE, Palmer-Toy DE, Hancock WS. Multilectin Affinity Chromatography for Characterization of Multiple Glycoprotein Biomarker Candidates in Serum from Breast Cancer Patients. Clin Chem. 2006;52(10):1897–1905. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.065862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qiu R, Regnier FE. Use of Multidimensional Lectin Affinity Chromatography in Differential Glycoproteomics. Anal Chem. 2005;77(9):2802–2809. doi: 10.1021/ac048751x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bertozzi CR, Kiessling LL. Chemical Glycobiology. Science. 2001;291(5512):2357–2364. doi: 10.1126/science.1059820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wei X, Li L. Comparative glycoproteomics: approaches and applications. Brief Funct Genomic Proteomic. 2009;8(2):104–113. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/eln053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diamandis EP. Mass Spectrometry as a Diagnostic and a Cancer Biomarker Discovery Tool: Opportunities and Potential Limitations. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2004;3(4):367–378. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R400007-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu F, Iqbal K, Grundke-Iqbal I, Hart GW, Gong C-X. O-GlcNAcylation regulates phosphorylation of tau: A mechanism involved in Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(29):10804–10809. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400348101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Botella-Lopez A, Burgaya F, Gavin R, Garcia-Ayllon MS, Gomez-Tortosa E, Pena-Casanova J, Urena JM, Del Rio JA, Blesa R, Soriano E, Saez-Valero J. Reelin expression and glycosylation patterns are altered in Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(14):5573–5578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601279103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rudd PM, Endo T, Colominas C, Groth D, Wheeler SF, Harvey DJ, Wormald MR, Serban H, Prusiner SB, Kobata A, Dwek RA. Glycosylation differences between the normal and pathogenic prion protein isoforms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(23):13044–13049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hutchinson WL, Noble GE, Hawkins PN, Pepys MB. The pentraxins, C-reactive protein and serum amyloid P component, are cleared and catabolized by hepatocytes in vivo. J Clin Invest. 1994;94(4):1390–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI117474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mold C, Baca R, Du Clos TW. Serum amyloid P component and C-reactive protein opsonize apoptotic cells for phagocytosis through Fcgamma receptors. J Autoimmun. 2002;19(3):147–54. doi: 10.1006/jaut.2002.0615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Togashi S, Lim SK, Kawano H, Ito S, Ishihara T, Okada Y, Nakano S, Kinoshita T, Horie K, Episkopou V, Gottesman ME, Costantini F, Shimada K, Maeda S. Serum amyloid P component enhances induction of murine amyloidosis. Lab Invest. 1997;77(5):525–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han DK, Eng J, Zhou H, Aebersold R. Quantitative profiling of differentiation-induced microsomal proteins using isotope-coded affinity tags and mass spectrometry. Nat Biotech. 2001;19(10):946–951. doi: 10.1038/nbt1001-946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geer LY, Markey SP, Kowalak JA, Wagner L, Xu M, Maynard DM, Yang X, Shi W, Bryant SH. Open Mass Spectrometry Search Algorithm. J Proteome Res. 2004;3(5):958–964. doi: 10.1021/pr0499491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khatri P, Draghici S, Ostermeier GC, Krawetz SA. Profiling Gene Expression Using Onto-Express. Genomics. 2002;79(2):266–270. doi: 10.1006/geno.2002.6698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramstrom M, Hagman C, Mitchell JK, Derrick PJ, Hakansson P, Bergquist J. Depletion of high-abundant proteins in body fluids prior to liquid chromatography fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry. J Proteome Res. 2005;4(2):410–416. doi: 10.1021/pr049812a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brzeski H, Katenhusen RA, Sullivan AG, Russell S, George A, Somiari RI, Shriver C. Albumin depletion method for improved plasma glycoprotein analysis by two-dimensional difference gel electrophoresis. Biotechniques. 2003;35(6):1128–32. doi: 10.2144/03356bm01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baron AT, Lafky JM, Boardman CH, Balasubramaniam S, Suman VJ, Podratz KC, Maihle NJ. Serum sErbB1 and epidermal growth factor levels as tumor biomarkers in women with stage III or IV epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 1999;8(2):129–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Edmund AW, Brice MB, Friedlander W, Bateman ED, Kirsch RE. Serum Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Activity, Concentration, and Specific Activity in Granulomatous Interstitial Lung Disease, Tuberculosis, and COPD. Chest. 1995;107(3):706–710. doi: 10.1378/chest.107.3.706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hiroaki S, Shunichi T, Kuniyuki K, Masahide I, Michio M, Nobuaki K. Serum concentration of CD44 variant 6 and its relation to prognosis in patients with gastric carcinoma. Cancer. 1998;83(6):1094–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hunter N, Foster J, Chong A, McCutcheon S, Parnham D, Eaton S, MacKenzie C, Houston F. Transmission of prion diseases by blood transfusion. J Gen Virol. 2002;83:2897–2905. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-11-2897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang BG, Cheng X, Yin SM, Pan T, Zhang HT, Wong PK, Kang SC, Xiao F, Yan HM, Li CY, Wolfe LL, Miller MW, Wisniewski T, Greene MI, Sy MS. Test for detection of disease-associated prion aggregate in the blood of infected but asymptomatic animals. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2007;14(1):36–43. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00341-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rudd PM, Merry AH, Wormald MR, Dwek RA. Glycosylation and prion protein. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2002;12(5):578–586. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00377-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fournier ML, Gilmore JM, Martin-Brown SA, Washburn MP. Multidimensional separations-based shotgun proteomics. Chem Rev. 2007;107(8):3654–3686. doi: 10.1021/cr068279a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dowell JA, VanderHeyden W, Li L. Rat Neuropeptidomics by LC-MS/MS and MALDI-FTMS: Enhanced Dissection and Extraction Techniques Coupled with 2D RP-RP HPLC. J Proteome Res. 2006;5(12):3368–3375. doi: 10.1021/pr0603452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gilar M, Olivova P, Daly AE, Gebler JC. Two-dimensional separation of peptides using RP-RP-HPLC system with different pH in first and second separation dimensions. J Sep Sci. 2005;28(14):1694–1703. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200500116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hsu JL, Huang SY, Chow NH, Chen SH. Stable-Isotope Dimethyl Labeling for Quantitative Proteomics. Anal Chem. 2003;75(24):6843–6852. doi: 10.1021/ac0348625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Song X, Bandow J, Sherman J, Baker JD, Brown PW, McDowell MT, Molloy MP. iTRAQ Experimental Design for Plasma Biomarker Discovery. J Proteome Res. 2008;7(7):2952–2958. doi: 10.1021/pr800072x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zybailov B, Coleman MK, Florens L, Washburn MP. Correlation of Relative Abundance Ratios Derived from Peptide Ion Chromatograms and Spectrum Counting for Quantitative Proteomic Analysis Using Stable Isotope Labeling. Anal Chem. 2005;77(19):6218–6224. doi: 10.1021/ac050846r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Watanabe J, Grijalva V, Hama S, Barbour K, Berger FG, Navab M, Fogelman AM, Reddy ST. Hemoglobin and Its Scavenger Protein Haptoglobin Associate with ApoA-1-containing Particles and Influence the Inflammatory Properties and Function of High Density Lipoprotein. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(27):18292–18301. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.017202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wei X, Herbst A, Schmidt J, Aikent J, Li LJ. Facilitating Discovery of Prion Disease Biomarkers by Quantitative Glycoproteomics. LC GC North America. 2009;27(2):154–162. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Edelman GM, Wang JL. Binding and functional properties of concanavalin A and its derivatives. III. Interactions with indoleacetic acid and other hydrophobic ligands. J Biol Chem. 1978;253(9):3016–3022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Holtzman DM, Pitas RE, Kilbridge J, Nathan B, Mahley RW, Bu G, Schwartz AL. Low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein mediates apolipoprotein E-dependent neurite outgrowth in a central nervous system-derived neuronal cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 1995;92(21):9480–9484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jiang Q, Lee CYD, Mandrekar S, Wilkinson B, Cramer P, Zelcer N, Mann K, Lamb B, Willson TM, Collins JL, Richardson JC, Smith JD, Comery TA, Riddell D, Holtzman DM, Tontonoz P, Landreth GE. ApoE Promotes the Proteolytic Degradation of Aβ. Neuron. 2008;58(5):681–693. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Diedrich JF, Minnigan H, Carp RI, Whitaker JN, Race R, Frey W, Haase AT. Neuropathological Changes in Scrapie and Alzheimers-Disease Are Associated with Increased Expression of Apolipoprotein-E and Cathepsin-D in Astrocytes. J Virol. 1991;65(9):4759–4768. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.9.4759-4768.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leila HC, Alison G, Richard SGK, Edward JT, Kelvin HL. Apolipoprotein E and other cerebrospinal fluid proteins differentiate ante mortem variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease from ante mortem sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Electrophoresis. 2002;23(14):2242–2246. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200207)23:14<2242::AID-ELPS2242>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pepys MB, Booth DR, Hutchinson WL, Gallimore JR, Collins PM, Hohenester E. Amyloid P component. A critical review. Amyloid-Journal of Protein Folding Disorders. 1997;4(4):274–295. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kalaria RN, Golde TE, Cohen ML, Younkin SG. Serum Amyloid-P in Alzheimers-Disease - Implications for Dysfunction of the Blood-Brain-Barrier. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1991;640:145–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Akiyama H, Yamada T, Kawamata T, McGeer PL. Association of Amyloid-P Component with Complement Proteins in Neurologically Diseased Brain-Tissue. Brain Res. 1991;548(1–2):349–352. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91148-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Coria F, Castano E, Prelli F, Larrondolillo M, Vanduinen S, Shelanski ML, Frangione B. Isolation and Characterization of Amyloid P-Component from Alzheimers-Disease and Other Types of Cerebral Amyloidosis. Laboratory Investigation. 1988;58(4):454–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pepys MB, Herbert J, Hutchinson WL, Tennent GA, Lachmann HJ, Gallimore JR, Lovat LB, Bartfai T, Alanine A, Hertel C, Hoffmann T, Jakob-Roetne R, Norcross RD, Kemp JA, Yamamura K, Suzuki M, Taylor GW, Murray S, Thompson D, Purvis A, Kolstoe S, Wood SP, Hawkins PN. Targeted pharmacological depletion of serum amyloid P component for treatment of human amyloidosis. Nature. 2002;417(6886):254–259. doi: 10.1038/417254a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Omtvedt LA, Wien TN, Myran T, Sletten K, Husby G. Serum amyloid P component in mink, a non-glycosylated protein with affinity for phosphorylethanolamine and phosphorylcholine. Amyloid-Journal of Protein Folding Disorders. 2004;11(2):101–108. doi: 10.1080/13506120410001728063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The list of proteins identified at each time point (108, 158, and 198 dpi) showing the sequence coverage, unique peptides, spectral count, expression ratio and standard deviations. N/A indicates that the XPRESS function was unable to use a peptide profile to calculate the expression ratio.

The list of peptides identified at each time point and each replicate experiments. The lists of identifications include amino acid sequences, theoretical and observed precursor masses and confidence of identification.