Abstract

In this study we compared two different D2/3 receptor ligands, [18F]fallypride and [18F]desmethoxyfallypride ([18F]DMFP) with respect to duration of the scan, visualization of extrastriatal receptors and binding potentials in the rat brain. In addition we studied the feasibility of using these tracers following a period of awake tracer uptake, during which the animal may perform a behavioral task. Male Sprague Dawley rats were imaged with [18F]fallypride and with [18F]DMFP in four different studies using microPET. All scans were performed under isoflurane anesthesia. The first (test) and second (retest) study were 150 min baseline scans. No retest scans were performed with [18F]DMFP. A third study was a 60 minutes awake uptake of radiotracer followed by a 90 minutes scan. A fourth study was a 150 min competition scan with haloperidol (0.2 mg/Kg) administered via tail vein at 90 min post [18F]fallypride injection and 60 min post [18F]DMFP. For the test-retest studies, binding potential (BPND) was measured using both Logan non-invasive (LNI) method and the interval ratios (ITR) method. Cerebellum was used as a reference region. For the third study the binding was measured only with the ITR method and the results were compared to the baseline results. Studies showed that the average transient equilibrium time in the dorsal striatum was at 90 min for [18F]fallypride and 30 min for [18F]DMFP. The average binding potentials (BPND) for [18F]fallypride were 14.4 in dorsal striatum (DSTR), 6.8 in ventral striatum (VSTR), 1.3 in substantia nigra/ventral tegmental area (SN/VTA), 1.4 in colliculi (COL), and 1.5 in central grey area (CG). In the case of [18F]DMFP the average BPND values were 2.2 in DSTR, 2.7 in VSTR, and 0.8 in SN/VTA. The haloperidol blockade showed detectable decrease in binding of both tracers in striatal regions with a faster displacement of [18F]DMFP. No significant changes in BPND of [18F]fallypride due to the initial awake state of the animal was found whereas BPND of [18F]DMFP was significantly higher in the awake state compared to baseline. We were able to demonstrate that dynamic PET using MicroPET Inveon allows quantification of both striatal and extrastriatal [18F]fallypride binding in rats in vivo. Quantification of the striatal regions could be achieved with [18F]DMFP.

Keywords: PET (positron emission tomography), D2 receptors, small animals, preclinical, imaging, binding potential, striatum, extrastriatal, [18F]Fallypride, [18F]Desmethoxyfallypride

INTRODUCTION

With the continuous development of small animal preclinical PET technology and the increased use of animal models of dopamine neurotransmission, there is a growing interest in the use of benzamide radioligands in studies of dopamine system. The longer physical half-life of fluorine-18 make [18F]fallypride and [18F]desmethoxyfallypride ([18F]DMFP) suitable dopamine D2/3 receptor radioligands that can be used in preclinical research in various animal models. Recently, imaging animals following a behavioral task has come to focus. Studies with [11C]raclopride, an established reversible D2/D3 radioligand have been performed in freely moving rats (Patel et al., 2008). For this to be possible the animals need to be awake while at the same time allow the dopaminergic system to be altered while monitored using the D2/D3 radioligands. Using high affinity and displaceable radioligands labeled with 18F would allow sufficient time for the task and measurement.

[18F]Fallypride is a highly selective dopamine D2/3 receptor radioligand that has been shown to yield high specific/non-specific ratios in non-human primates in vivo [1]. [18F]Fallypride is of interest because of its high affinity for both striatal and extrastriatal binding which has been demonstrated in studies of non-human primates and humans (Christian et al., 2000; Christian et al., 2004; Christian et al., 2009; Mukherjee et al., 2002; Slifstein et al., 2004a). It has also been shown that it responds to amphetamine-induced dopamine release (Mukherjee et al., 2005; Slifstein et al., 2004a). Rodent imaging studies using [18F]fallypride have recently been reported (Tantawy et al., 2009).

[18F]DMFP is a ligand with affinity in vitro similar to that of [11C]raclopride, another D2/3 receptor radiotracer. [18F]DMFP presents the advantage of being labeled with fluorine-18 and therefore does not require an on-site cyclotron. [18F]DMFP kinetics and quantification have been studied in non-human primates and humans using PET (Grunder et al., 2003; Mukherjee et al., 1996; Siessmeier et al., 2005). Recent microPET studies in mice (Rominger et al., 2010a) showed detectable change in [18F]DMFP binding as a response to administration of both reserpine, a dopamine VMAT transporter blocker and amphetamine, a drug known to increase the endogenous dopamine release. However, there is a lack of published data on PET studies with [18F]DMFP in rats.

In this work we intended to evaluate the potential for quantification of in vivo [18F]fallypride and [18F]DMFP binding in rats using dynamic PET and compare the two agents under baseline conditions. In addition we performed PET scans in which the animals were allowed to be awake for a period of time between tracer injection and start of the scan and compared the results (binding) to those with animals under anesthesia for the whole duration of the experiment. Lastly, we evaluated the dissociation of both tracers in vivo in response to pharmacological intervention with haloperidol, a dopamine D2/D3 receptor antagonist.

As the collection of blood samples from small animals is often difficult we limited our methodology to a practical approach used by majority of researchers in preclinical PET which is employing non-invasive methods for calculations of binding potentials. We used Logan plot analysis as well as an interval method based on tissue ratios. Both methods rely on tracer achieving transient equilibrium following a bolus injection, a state in which blood-tissue distribution volumes in target and reference regions become equal. The reference brain region, which in our case was cerebellum, is assumed to have a minimal presence or a lack of D2/3 receptors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tracer Synthesis

[18F]fallypride (or [18F]N-allyl-5-fluorpropylepidepride) was synthesized as described originally by. [18F]desmethoxyfallypride (or (S)-N-((1-allyl-2-pyrrolidinyl)methyl)-5-(3-18F-fluoropropyl)-2-methoxybenzamide ) was synthesized as reported in (Mukherjee et al., 1995; Mukherjee et al., 1996). The specific activity of [18F]fallypride and [18F]DMFP exceeded 2 Ci/μmol at the end of synthesis.

PET Scanning

This study was conducted under protocols approved by the University of California Irvine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. A total of nine healthy male Sprague-Dawley rats (240–310 g) were used for the PET experiments, five for the [18F]fallypride scans and four for the [18F]DMFP scans. The rodents were housed in individual cages, and were kept in a climate controlled room (24.4°C), with a 12:12-hour light cycle. During housing subjects had free access to food and water. Subjects were fasted in the imaging room, in a dark quiet place, for 4–6 hours prior to experiments. In preparation for the scans, the rats were anesthetized with isoflurane and then maintained under anesthesia during the scan (4% induction, 2.5% maintenance). The anesthesia line was attached to the animal via a nose-cone. The temperature of the animal was maintained constant with a water-circulating heating pad attached.. The average injected dose of [18F]fallypride was 28.4 ± 3.5 MBq and that of [18F]DMFP was 25.4 ± 2.87 MBq.

Five rats underwent the following [18F]fallypride experiments:

Study 1 (test) - the rats were where injected with [18F]fallypride via tail vein and scanned for 150 minutes under isoflurane anesthesia.

Study 2 (retest) - a repeat of Study 1 after an average period of 26 days (min 6 days, max 40 days).

Study 3 (awake uptake) - the rats were briefly anesthetized for i.v. [18F]fallypride injection then allowed to be conscious for 60 min, induced into anesthesia with 4% isoflurane and then scanned for 90 minutes (150 minutes experiment)

Study 4 (blockade) - the rats were anesthetized and scanned for 150 minutes. Haloperidol (0.2 mg/Kg) was administered via tail injection at 90 minutes post-[18F]fallypride injection. The order of the experiments was randomized.

Four rats underwent [18F]DMFP experiments. All four received control scans for 150 min (Study 1). Two of them underwent additional Study 3 (awake uptake for 60 min) and Study 4 (haloperidol blockade). In the case of Study 4 haloperidol (0.2 mg/Kg) was administered via tail injection at 60 minutes post [18F]DMFP injection.

Data were acquired using an Inveon dedicated PET scanner for small animals (Siemens Medical Solutions, Knoxville, TN) with a transaxial FWHM of 1.5 mm, and axial FWHM of 1.3 mm (Bao et al., 2009; Constantinescu and Mukherjee, 2009). A 350–650 keV photon energy window and 3.43 ns timing window were used for data acquisition. The list-mode data were rebinned into 3D sinograms of span 3 and ring difference 79. The data from 150 min acquisition was histogrammed in 41 time frames (10 × 1 min, 5 × 2 min, 26 × 5 min) and the data from 90 min acquisition was histogrammed into 18 frames of 5 min each. Random events were subtracted prior to reconstruction. The images were reconstructed using Fourier rebinning and 2-dimensional filtered back-projection (2D FBP) method ( ramp filter and cutoff at Nyquist frequency) with an image matrix of 128×128×159, resulting in a pixel size of 0.77 mm and a slice thickness of 0.796 mm. All dynamic images were corrected for radioactive decay. Attenuation correction was performed using a 10-min transmission scan with a 57Co point source prior to tracer injection. In the case of awake uptake experiments the transmission acquisition was performed following the emission scan. Normalization of detector responses was also applied using a cylinder source inversion method.

Image Analysis

Processing of reconstructed images was performed with PMOD software package (PMOD Technologies). MicroPET images were normalized to the standard space described by the stereotaxic coordinates of Paxinos & Watson (Paxinos and Watson, 1982) via co-registration to an MRI rat template (Schweinhardt et al., 2003). The size of the template image was 80 × 63 × 108 voxels with a voxel size of 2 mm. The template includes a scale factor of 10 in order to roughly match the size of the human brain and facilitate analysis with SPM software. Bregma was set as the origin of coordinates system. The spatial extent of the template volume (bounding box ) was from −80 to 80 mm in X direction (left to right of the midline, through the sagital planes), −120 to 6 mm in the Y direction (ventral to dorsal, through the horizontal planes) and from −156 to 60 mm in the Z direction (posterior to anterior, through the coronal planes). Standard 3D volumes of interest (VOIs) were drawn on the MR template for dorsal striatum (DSTR), ventral striatum (VSTR), colliculi (COL), substantia nigra/ventral tegmental area (SN/VTA), central gray (CG) and cerebellum (CER). The location of the VOIs were confirmed by examination of the Paxinos & Watson rat atlas (4th edition). The size of each predefined VOI was smaller than actual anatomical extent of the brain structure in order to avoid the negative effects of spillover. The VOIs over DSTR and VSTR consisted of pair of spheres with 2 mm diameter and placed symmetrically with respect to the midline. The spheres centers in template coordinates with respect to bregma, were (x,y,z) = (+\−28, −48, 4) mm, for right\left DSTR and (x,y,z) = (+\−15, −76, 14) mm for right\left VSTR. For the extrastriatal structures, the VOIs consisted of a series of ellipses (2D) placed on multiple coronal planes, with the centers of mass at (+\−14, −38, −70) mm (right\left superior COL), (+\−19, −39, −88) mm (right\left inferior COL), (+\−21, −77, −54) mm, (+\−21, −77, −88) (right\left SN) mm, (+\−8, −77, −59) mm (right\left VTA), and (−1, −52, −69) mm (CG). The superior and inferior colliculi were combined into a single COL VOI as well as substantia nigra (SN) with ventral tegmental area (VTA) into a single SN/VTA VOI. The cerebellum VOI consisted of two ellipsoids placed on lateral lobes and centered at (+\−29, −43, −128) mm with a long axis of 3 mm and a short axis of 2 mm. The left and right VOIs for each structure were combined into a single VOI.

The dynamic PET images were first summed and the sum image was resliced using the Fusion toolbox of PMOD to match the size of the template. All sum images were subjected to an common initial spatial transformation consisting of a scale factor (zoom) of 10 and a rotation of 180 degrees around the z axis so that the orientation of the brain to roughly match the orientation of the MR brain template. Through subsequent rigid transformations (translations and rotations) applied to each sum image the brain was co-registered to match the template and therefore the Paxinos atlas. The resulted transformation matrix for each subject was subsequently applied to all the images in the dynamic series. Time activity curves (TACs) were extracted for each VOI from the dynamic PET data.

Kinetic analysis

Kinetic analysis was performed using a specialized PMOD toolbox. Binding potential (BPND) was calculated using Logan non-invasive method (Logan et al., 1996). BPND (=“DVR−1”) was estimated graphically from the equation

| (1) |

where Ct(t) is the time dependent tracer concentration within the region with specific binding, and Cref(t) is the tracer concentration within the region devoid of binding sites (i.e. cerebellum). DVR is the distribution volume ratio, k′2 (min−1) is the transfer rate between the free and plasma for cerebellum. int′ is the intercept of the linear plot. At the time when the change in the target region equals that in the reference region (pseudo equilibrium) the slope (DVR) becomes constant and can be estimated from a simple linear fit. Prior to linear regression in (1), the average rate k′2 for cerebellum was estimated from fitting the simplified reference tissue model (SRTM) (Lammertsma and Hume, 1996) to the first 90 minutes of data from a region placed on the whole striatum. Striatum was used for the SRTM fit due the expected high binding and therefore low statistical noise. The model equation for SRTM is

| (2) |

where R1 (=K1/K′1)is the relative tracer delivery between the target and reference region. R1, k2, BPND are the only parameters estimated directly while k′2 (=k2/R1) is derived based on the assumption that K1/k2=K1′/k2′. K1, K′1 are the tracer delivery rates to the target and to the reference region respectively and k2 is the tissue-to-plasma clearance rate for the target region. For SRTM fitting Marquandt optimization method with 200 iterations was used. The estimated k′2 for each subject was then fixed and used subsequently for Logan analysis of all other brain regions. The cutoff of Logan plot was determined based on a preset error of 10% between the fit and the data. The LNI method was used only in Studies 1 and 2 for which full time activity curves were available for analysis.

In order to evaluate the BP in the of Study 3, in which full time activity curves were not available, we employed an interval method (ITR) (Ito et al., 1998) instead of Logan non-invasive method which generally requires data from time 0. Binding potential was estimated as

| (3) |

where Cb (t) = Ct (t) − Cref (t) is the specific binding curve. The curves were integrated between tS (=60 min) and tE (=150 min). For comparison the ITR method was applied to data from Studies 1 and 2 as well. For Study 4 with haloperidol administration we evaluated the in vivo dissociation constant by assuming the TAC post-haloperidol as being described by a exponential with the fall-off constant given by the dissociation constant, koff. Following haloperidol injection the tissue specific binding curve can be expressed as Cb (t) = Cb (tH) exp(−koff t) where Cb (tH ) is the value at time of haloperidol administration, tH (90 min for [18F]fallypride, 60 min for [18F]DMFP). koff can be estimated as the absolute slope value from a linear plot of ln(Cb (t)/Cb (tH )).

Statistical analysis

Percentage test-retest variability for [18F]fallypride measurements was calculated as the mean ratio between the absolute difference between test and retest and average test and retest values, |BPNDtest−BPNDretest|/((BPNDtest + BPNDretest)/2). Paired t-tests were employed to test for significant differences between samples at a significance level α=0.05.

RESULTS

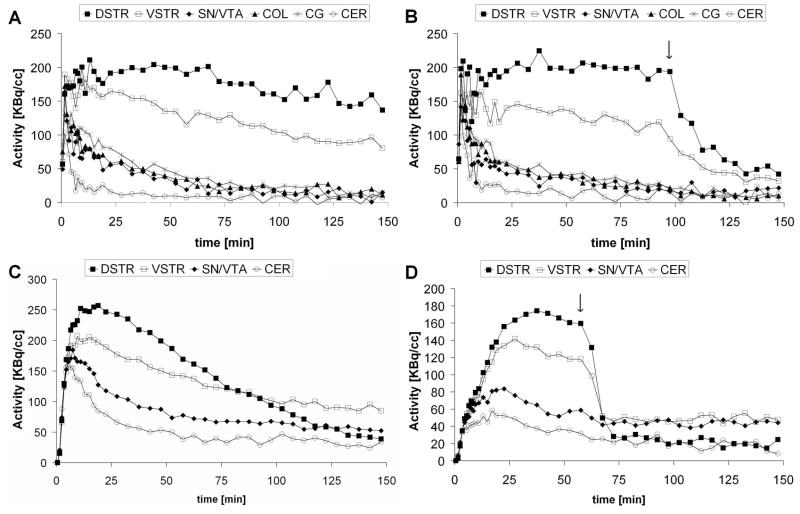

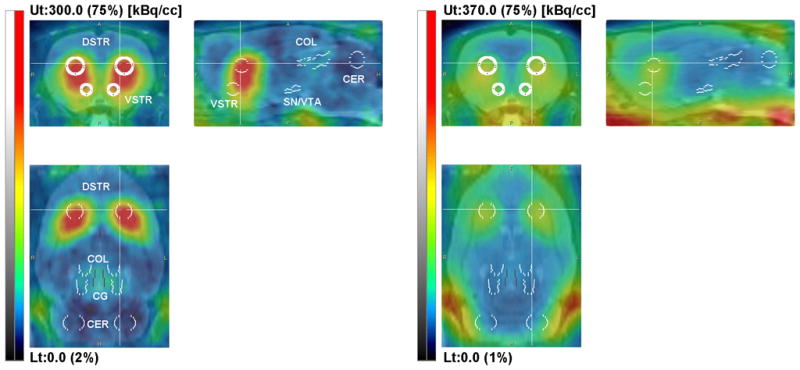

[18F]Fallypride images (Figure 1 ) showed high tracer uptake to both striatal (DSTR, VSTR) and extrastriatal regions (SN/VTA, COL, CG) and very low binding in the cerebellum. In the case of [18F]DMFP the tracer uptake was observed mostly in the striatum and to some degree in SN/VTA. Figures 2A, and 2C show a typical set of TACs for both [18F]fallypride and [18F]DMFP acquired in one of the control studies (Study 1).

Figure 1.

Representative coronal, sagital and horizontal sections of a rat brain showing [18F]fallypride (panel A) and [18F]DMFP (panel B) fused with the MR image template. The PET images were integrated over 16–90 min interval and the intensity was scaled relative to the whole image volume (upper threshold set to 75%). VOI placement on dorsal striatum (DSTR), ventral striatum (VSTR), substantia nigra/ventral tegmental area (SN/VTA), superior and inferior colliculi (COL), central gray (CG) and cerebellum (CER) are shown. All VOIs were placed on the axial slides of the MR image template. VOI labels are only shown in panel A.

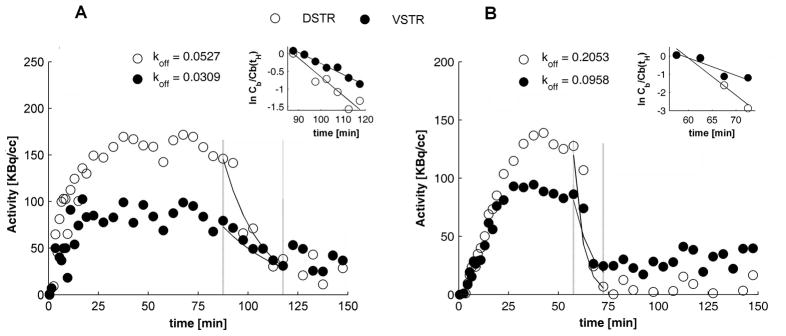

Figure 2.

Representative TACs from the baseline (A,C) and the haloperidol blockade (B,D) PET scans with both [18F]fallypride (top) and [18F]DMFP (bottom). Curves from dorsal striatum (DSTR), ventral striatum (VSTR), colliculi (COL), substantia nigra/ventral tegmental area (SN/VTA), central gray (CG) and cerebellum (CER) are shown. Arrows in panels B and D indicate the time of haloperidol administration.

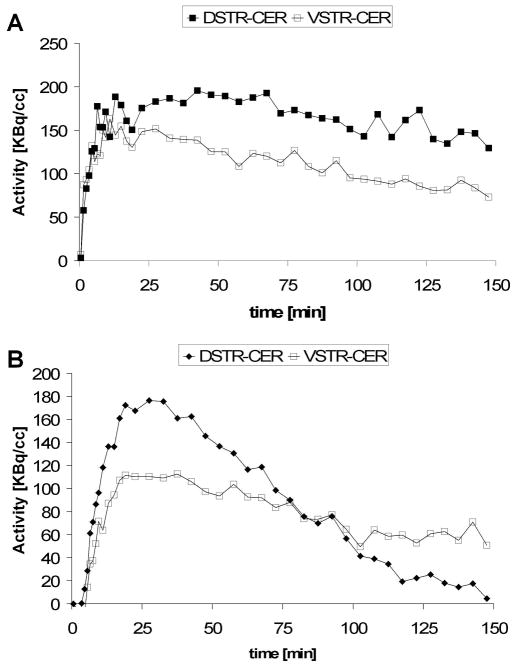

Representative tracer binding curves expressed as the difference between TACs in DSTR and VSTR are shown in Figure 3. [18F]fallypride binding reached the maximum value in DSTR at a time varying between 45 and 120 min post-injection with an average time of 90 min. For extrastriatal regions, which present a lower density of D2/3 receptors the time was shorter, with values as low as 20 min. In the case of [18F]DMFP the maximum binding was reached at an average time of 30 min post-injection in DSTR and 20 min in VSTR. In order to determine the optimum scan duration for both tracers we further repeated the computation of the binding potential using the LNI method with [18F]fallypride data sets truncated at 120, 90, 60, 45 min and with [18F]DMFP data sets truncated at 120, 90, 60, 45, and 30 min, respectively. In the case of [18F]fallypride 150 min data provided the lowest coefficient of variation of BPND in the control subjects (n=5) in both DSTR and VSTR. In the case of [18F]DMFP the lowest coefficient of variation in the control subjects (n=4) was for 90 min data in DSTR, and 60 min data in VSTR.

Figure 3.

Specific binding curves of [18F]fallypride (A) and [18F]DMFP (B) as a function of time. Curves for both dorsal (DSTR-CER) and ventral (VSTR-CER) striatum are shown. The plots indicate that pseudo-equilibrium for [18F]DMFP is reached within 30 min post bolus injection, while a longer time is required for [18F]fallypride to reach pseudo-equilibrium.

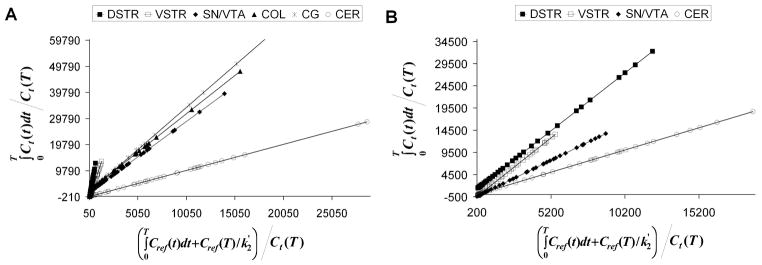

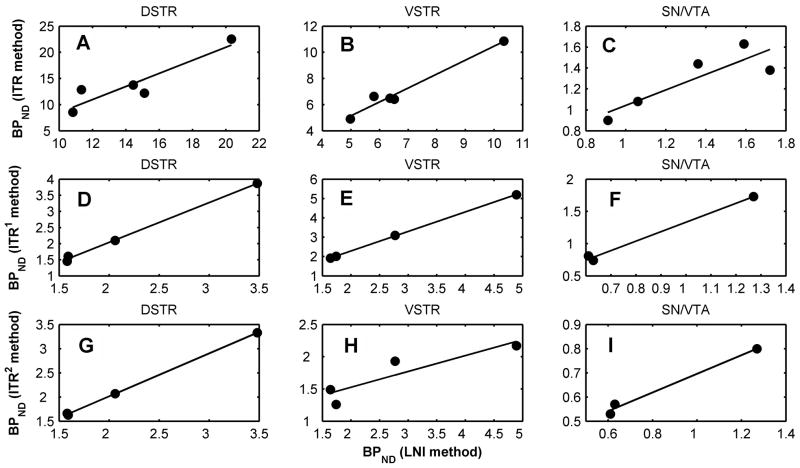

The binding potential values of [18F]fallypride calculated using LNI (representative Logan plots are shown in Figure 4) and ITR method (60 to 150 min) for striatal and extrastriatal regions are presented in Table I. For the control studies (Study 1 and 2) the k2′ values for cerebellum as obtained indirectly from SRTM method are also listed. The mean BPND values from Study 1 (test, n=5) computed with LNI method were 14.41 ± 3.8 in DSTR, 6.8 ± 2.07 in VSTR, 1.33 ± 0.34 in SN/VTA, 1.42 ± 0.47 in COL, and 1.53 ± 0.5 in CG. The retest values were 15.05 ± 4.71 in DSTR, 7.73 ± 2.90 in VSTR, 1.37 ± 0.40 in SN/VTA, 1.61 ± 0.56 in COL, and 1.82 ± 0.59 in CG. The percentage test-retest variability of BPND measurements using LNI method were 15.7% (DSTR), 17.3 % (VSTR), 14.8% (SN/VTA), 18.7% (COL), and 19.3% (CG) respectively. The test-retest variability values of measurements using the interval method (ITR) were 21.4% (DSTR), 30.8 % (VSTR), 22.3% (SN/VTA), 27.8% (COL), and 29.2% (CG) respectively. There was no statistical difference (paired t-test, p>0.05) between test and retest BPND values in all the regions. The BPND values obtained with LNI method were significantly correlated with those calculated with the ITR method in DSTR (y= 1.250x − 4.023, r=0.918, p=0.03), VSTR (y= 1.065x −0.176, r=0.986, p=0.002), SN/VTA (y = 0.742x + 0.301, r=0.869, p=0.05), and COL (y = 0.732x + 0.250, r = 0.889, p=0.04) and less correlated in CG (y = 0.583x + 0.440, r = 0.735, p=0.16). Correlation plots of BPND of [18F]fallypride in DSTR, VSTR, and SN/VTA as computed with the two methods are shown in Figure 5A, 5B, and 5C. Considering the BPND values calculated with LNI method as reference, the BPND calculated with ITR method between 60 and 150 min were positively biased in the striatal regions and negatively biased in the extrastriatal regions for both test and retest studies.

Figure 4.

Representative Logan graphical analysis plots for [18F]fallypride (A) and [18F]DMFP (B). The plot with the lowest slope (DVR=1) is that corresponding to the cerebellum (CER), which was used as a reference region.

Table I.

Regional binding potential of [18F]fallypride.

| k′2 | DSTR | VSTR | SN/VTA | COL | CG | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LNI | ITR | LNI | ITR | LNI | ITR | LNI | ITR | LNI | ITR | |||

| Study 1 (test) | Subject 1 | 0.27 | 11.34 | 12.88 | 5.8 | 6.63 | 0.91 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.79 | 1.01 | 0.76 |

| Subject 2 | 0.27 | 15.12 | 12.21 | 6.51 | 6.41 | 1.59 | 1.63 | 1.86 | 1.81 | 1.71 | 1.62 | |

| Subject 3 | 0.34 | 10.82 | 8.54 | 4.98 | 4.91 | 1.36 | 1.44 | 1.39 | 1.37 | 1.64 | 1.73 | |

| Subject 4 | 0.27 | 14.45 | 13.77 | 6.36 | 6.5 | 1.06 | 1.08 | 1.04 | 1.07 | 1.08 | 1.1 | |

| Subject 5 | 0.33 | 20.33 | 22.54 | 10.34 | 10.86 | 1.72 | 1.38 | 1.93 | 1.42 | 2.23 | 1.46 | |

| Mean± SD | 0.30 ± 0.04 | 14.41 ± 3.80 | 13.99 ± 5.18 | 6.80 ± 2.07 | 7.06 ± 2.24 | 1.33 ± 0.34 | 1.29 ± 0.29 | 1.42 ± 0.47 | 1.29 ± 0.38 | 1.53 ± 0.50 | 1.33 ± 0.40 | |

| Study 2 (retest) | Subject 1 | 0.3 | 12.82 | 13.03 | 5.4 | 5.98 | 0.72 | 0.61 | 0.98 | 0.79 | 0.96 | 0.83 |

| Subject 2 | 0.19 | 21.23 | 24.7 | 8.93 | 11.94 | 1.78 | 2.14 | 2.26 | 2.5 | 1.99 | 2 | |

| Subject 3 | 0.19 | 9.28 | 8.8 | 4.47 | 5.1 | 1.32 | 1.34 | 1.15 | 1 | 1.6 | 1.37 | |

| Subject 4 | 0.2 | 13.53 | 18.6 | 8.14 | 10.82 | 1.42 | 1.46 | 1.55 | 1.75 | 2.01 | 1.87 | |

| Subject 5 | 0.27 | 18.22 | 23.72 | 11.72 | 14.69 | 1.6 | 1.51 | 2.08 | 1.87 | 2.55 | 2.22 | |

| Mean± SD | 0.23 ± 0.05 | 15.05 ± 4.71 | 17.77 ± 6.84 | 7.73 ± 2.90 | 9.71 ± 4.07 | 1.37 ± 0.40 | 1.41 ± 0.55 | 1.61 ± 0.56 | 1.58 ± 0.69 | 1.82 ± 0.59 | 1.66 ± 0.56 | |

| Study 3 | Subject 1 | 18.12 | 8.65 | 1.2 | 1.09 | 0.99 | ||||||

| Subject 2 | 17.97 | 10.73 | 2.07 | 2.21 | 2.76 | |||||||

| Subject 3 | 14.86 | 8.27 | 1.86 | 1.71 | 2.05 | |||||||

| Subject 4 | 18.94 | 9.39 | 1.05 | 1.21 | 1.3 | |||||||

| Subject 5 | 13.21 | 7.95 | 1.23 | 0.92 | 1.48 | |||||||

| Mean± SD | 16.62 ± 2.46 | 9.00 ± 1.11 | 1.48 ± 0.45 | 1.43 ± 0.53 | 1.72 ± 0.70 | |||||||

LNI is Logan noninvasive method, also known as Logan graphical analysis using reference region ITR is the interval ratio method as defined by equation (3). The time interval was 60–150 min. k′2 (min−1) are the transfer rates between the free compartment and plasma for cerebellum estimated as a derived parameter using SRTM.

Figure 5.

Correlations between the BPND values as computed with LNI and ITR methods. Plots are shown for BPND within three brain regions (DSTR, VSTR, and SN/VTA). Top three panels (A,B, C) correspond to [18F]fallypride and an 60–150 min interval for the ITR method. For [18F]DMFP correlations are shown between BPND as computed with LNI and ITR with 2 different time intervals: ITR1, 60–150 min (panels D,E, F) and ITR2, 0–90 min (panels G, H, and I). The solid lines represent the linear fits.

Table II summarizes the BPND of [18F]DMFP. The mean BPND calculated using LNI were 2.22 ± 0.87 in DSTR (n=4), 2.72 ± 1.54 in VSTR (n=4), and 0.84 ± 0.38 in SN/VTA (n=3). One animal had a BPND value less than 0.5 in SN/VTA and it was excluded from the mean calculations as an outlier. BPND values calculated with ITR method using two intervals, 0–90 min (ITR1) and 60–150 min (ITR2) are also presented. For both intervals BPND values were correlated with those from LNI method. The regression equations and correlation coefficients were: y = 1.234x − 0.426, r = 0.999, p = 0.001 (DSTR); y = 1.011x + 0.267, r = 0.999, p = 0.001 (VSTR); y = 1.466x − 0.133, r = 0.996, p = 0.05 (SN/VTA) for LNI versus ITR1 and y = 0.889x + 0.237, r = 0.999, p = 0.0002 (DSTR); y = 0.247x + 1.031, r = 0.903, p = 0.09 (VSTR); y = 0.386x + 0.311, r=0.994, p=0.07, (SN/VTA ) for LNI versus ITR2. Correlation plots are shown in Figures 5D through 5I. The average bias between the LNI and ITR methods was very low for DSTR (6 % versus ITR1, 3 % versus ITR2) but rather large for VSTR (13 % versus ITR1, 31 % versus ITR2) and SN/VTA (−29 % versus ITR1, 20% versus ITR2).

Table II.

Regional binding potential of [18F]DMFP estimated using Logan non-invasive method and integral tissue ratios.

| k′2 | DSTR | VSTR | SN/VTA | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LNI | ITR1 | ITR2 | LNI | ITR1 | ITR2 | LNI | ITR1 | ITR2 | |||

| Study 1 | Subject 6 | 0.16 | 1.58 | 1.46 | 1.66 | 1.64 | 1.92 | 1.49 | 0.63 | 0.74 | 0.57 |

| Subject 7 | 0.27 | 1.59 | 1.61 | 1.63 | 1.74 | 2.01 | 1.26 | <0.50 | <0.50 | <0.50 | |

| Subject 8 | 0.11 | 3.48 | 3.87 | 3.33 | 4.89 | 5.2 | 2.17 | 1.27 | 1.73 | 0.8 | |

| Subject 9 | 0.24 | 2.06 | 2.1 | 2.07 | 2.77 | 3.1 | 1.93 | 0.61 | 0.81 | 0.53 | |

| Mean± SD | 0.20 ± 0.07 | 2.18 ± 0.90 | 2.26 ± 1.11 | 2.17± 0.80 | 2.76 ± 1.51 | 3.06 ± 1.53 | 1.71 ± 0.41 | 0.84 ± 0.38* | 1.09 ± 0.55* | 0.63 ± 0.15* | |

| Study 3 | Subject 6 | 4.13 | 3.68 | 1.1 | |||||||

| Subject 7 | 3.93 | 3.22 | 1.19 | ||||||||

| Mean± SD | 4.03 ± 0.14 | 3.45 ± 0.33 | 1.15 ± 0.06 | ||||||||

integral was on the interval between 60–150 min

integral was on the interval between 0–90 min

values less than 0.5 were excluded from mean and SD calculations.

In the case of Study 3 using [18F]fallypride (awake animals for 60 min) the BPND values were not statistically different (paired t-test, p>0.05) from those resulting from either Study 1 and 2 (ITR method, 60–150 min interval), in any of the brain regions. However, there was no significant correlation between the BPND values from each pair of studies (Pearson test, p>0.05).

In the case of [18F]DMFP the BPND values of the 2 animals that underwent Study 3 (awake uptake for 60 min) were 2.6 times higher in DSTR (1.8 in VSTR) than those from the control studies performed entirely under anesthesia.

The effects of haloperidol administered at 90 min ([18F]fallypride) and 60 min ([18F]DMFP) post-injection, respectively are illustrated in Figures 2B and 2D. For both tracers we note the fast drop in activity due to haloperidol blockage of the receptor sites. Both striatal and extrastriatal regions showed reduction in binding as a response to haloperidol. The average dissociation constant of [18F]fallypride was 0.0467 min−1 for DSTR and 0.0404 min−1 for VSTR. For [18F]DMFP the values were 0.2837 min−1 in DSTR, and 0.1909 min−1 in VSTR. All koff values are presented in Table III. Due to low number of counts at the time of haloperidol administration the dissociation constant of [18F]fallypride could not be reliably calculated for extrastriatal regions.

Table III.

The in vivo dissociation constants of [18F]fallypride and [18F]DMFP due to haloperidol

| koff[min−1] | ||

|---|---|---|

| [18F]Fallypride (n=5) | [18F]DMFP (n=2) | |

| DSTR | 0.0467 ± 0.0259 | 0.2445 ± 0.0555 |

| VSTR | 0.0404 ± 0.0148 | 0.1433 ± 0.0673 |

DISCUSSION

We were able to demonstrate that dynamic PET using MicroPET Inveon allows quantification of both striatal and extrastriatal [18F]fallypride binding in rats in vivo. In the case of [18F]DMFP the quantification was possible only in the striatal regions. The test -retest variability for BPND of [18F]fallypride computed with LNI method was in the interval 15–20% for al regions. When ITR method was used the variability was much larger, up to 30%. However, the variability should be low enough to be exceeded by changes in occupancy due to drugs such as amphetamine, which in PET studies on baboons has been shown to cause changes in binding close to 50% in the striatum (Slifstein et al., 2004b). This shows that in group studies with drugs that cause dopamine release or block the dopamine re-uptake it is possible to exceed the threshold of detectability of the respective drugs’ effects. It is important to note that we used filtered-backprojection to reconstruct the images. Iterative reconstruction methods such as the ordered subsets expectation maximization (OSEM) has been shown to markedly improve the test-retest variability of binding potential measurements (Catafau et al., 2008). We did not perform retest studies for the animals imaged with [18F]DMFP. Recent in vivo microPET studies with [18F]DMFP in mice have shown a 62% decrease in binding potential in response to amphetamine and a 33% increase due to reserpine (Rominger et al., 2010b). Similar studies need to be performed in rats in order to quantitatively evaluate changes in the [18F]DMFP binding in response to drugs.

The BPND values of [18F]fallypride calculated with ITR method were biased compared to those calculated with the LNI method and varied across the regions. The integration interval for the ITR method has to include the time of transient equilibrium. For the purpose of comparing Study 3 with the control we opted for a fixed time interval (60–150 min). However, this interval does not include the time of transient equilibrium, especially for the extrastriatal regions with a lower receptor density than striatum. As discussed in (Carson et al., 1993; Slifstein, 2008) caution must be exercised when using the interval method with late in the scan integration times as the bias with respect to the “gold standard”, i.e. binding potential calculated with kinetic modeling and plasma input function method, depends on the peripheral clearance of radioligand.

Both striatal and extrastriatal regions showed reduction in [18F]fallypride and [18F]DMFP binding in response to haloperidol administration. However, binding potential of [18F]DMFP in extrastriatal regions such colliculi and SN/VTA was low and variability was very high. The size of the VOIs placed on the extrastriatal regions were rather small and it is possible that, due to partial volume effects the activity could not be fully recovered, which could lead to an underestimation of binding potential values in those regions. No partial volume correction was performed in this study.

As opposed to [18F]fallypride the BPND of [18F]DMFP in the VSTR was comparable in magnitude to that in DSTR. The examination of TACs after haloperidol showed that the concentration of tracer in VSTR is maintained at a level above that in the DSTR (Figure 2D). Since haloperidol blocks more or less non-selectively both D2 and D3 varieties of receptors (Kulagowski et al., 1996) this observation points to a higher degree of non-specific binding in ventral striatum compared to the dorsal striatum. The large fraction of non-specific binding by [18F]DMFP has been suggested by the studies in humans (Grunder et al., 2003). One can also speculate that the relative affinity of DMFP for D3 receptors with respect to haloperidol is much higher than that for D2 receptors. In vitro mice studies have shown predominant localization of D3 receptors in that Nucleus Accumbens/ventral striatum (Bouthenet et al., 1991). While our study does not provide the tools to support such a hypothesis, further investigation with D3 selective antagonists may be designed to differentially evaluate the occupancy of D3 versus D2 receptors in rat brain.

[18F]Fallypride uptake in awake rats followed by late isoflurane anesthesia did not cause significant change in the estimated binding potential, BPND compared to the case of full scan under anesthesia. This shows that behavioral experiments could be designed to take place during the initial tracer uptake period, followed by a 60 min scan and the results compared to control studies performed under anesthesia. The experimental procedure could be refined by preparation of animals through implantation of a catheter for tracer delivery in advance so that the animals could be maintained awake for the entire period between tracer administration and induction of anesthesia for the scan (Patel et al., 2008). In our case the animals were anesthetized briefly to allow the injection of tracer.

The BPND values from [18F]DMFP scans performed following the period of awake tracer uptake were significantly higher than those from the full scan under anesthesia. This finding may indicate that anesthesia with isoflurane impacts [18F]DMFP delivery and binding. The bias is not likely due to the late (60–150 min) interval used in the ITR method since, in the case of control studies the BPND values calculated using the early (0–90 min) interval were comparable to those from the late interval (60–150 min).

The fast kinetics of [18F]DMFP allows for a reduced scan time, up to 90 min, compared to that required for [18F]fallypride (up to 150 min), which can be an advantage for both animal and human studies. The BPND values computed using the integral ratio method for an 0–90 min time interval compare well and are highly correlated with those computed using LNI method. The binding potential of [18F]DMFP is comparable in magnitude to that of similar D2R tracers such as 11C-raclorpride but labeling with 18F reduces the need for on-site cyclotron. These features make [18F]DMFP an attractive radioligand for experiments in rodents.

Figure 6.

Representative plots of specific binding curves for dorsal (DSTR, open circles) and ventral (VSTR, filled circles) striatum for [18F]fallypride (A) and [18F]DMFP (B) from haloperidol displacement experiments. Dotted vertical lines mark the post-haloperidol time intervals that were used in computation of koff due to haloperidol. Solid lines show the exponential fall-off in the specific binding. The insets show plots of ln C(t)/C(tH) and their corresponding linear fits (solid lines). koff is given by the absolute slope value of each fitting line. In the case shown the fit equations for [18F]fallypride (plot A) were y=−0.0527x−0.0041, r = 0.940, in DSTR, y=−0.0309x−0.1107, r = 0.985 in VSTR, and for [18F]DMFP they were y=−0.2053x−0.4108, r = 0.963, in DSTR and y=−0.0957x−0.1343, r= 0.934 in VSTR.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by Grant Number R01EB006110 (JM) from the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB).

Reference List

- Bao Q, Newport D, Chen M, Stout DB, Chatziioannou AF. Performance evaluation of the Inveon dedicated PET preclinical tomograph based on the NEMA NU-4 standards. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:401–408. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.056374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouthenet ML, Souil E, Martres MP, Sokoloff P, Giros B, Schwartz JC. Localization of dopamine D3 receptor mRNA in the rat brain using in situ hybridization histochemistry: comparison with dopamine D2 receptor mRNA. Brain Res. 1991;564:203–219. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91456-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson RE, Channing MA, Blasberg RG, Dunn BB, Cohen RM, Rice KC, Herscovitch P. Comparison of bolus and infusion methods for receptor quantitation: application to [18F]cyclofoxy and positron emission tomography. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1993;13:24–42. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1993.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catafau AM, Bullich S, Danus M, Penengo MM, Cot A, Abanades S, Farre M, Pavia J, Ros D. Test-retest variability and reliability of 123I-IBZM SPECT measurement of striatal dopamine D2 receptor availability in healthy volunteers and influence of iterative reconstruction algorithms. Synapse. 2008;62:62–69. doi: 10.1002/syn.20465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian BT, Narayanan T, Shi B, Morris ED, Mantil J, Mukherjee J. Measuring the in vivo binding parameters of [18F]-fallypride in monkeys using a PET multiple-injection protocol. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24:309–322. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000105020.93708.DD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian BT, Narayanan TK, Shi B, Mukherjee J. Quantitation of striatal and extrastriatal D-2 dopamine receptors using PET imaging of [(18)F]fallypride in nonhuman primates. Synapse. 2000;38:71–79. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(200010)38:1<71::AID-SYN8>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian BT, Vandehey NT, Fox AS, Murali D, Oakes TR, Converse AK, Nickles RJ, Shelton SE, Davidson RJ, Kalin NH. The distribution of D2/D3 receptor binding in the adolescent rhesus monkey using small animal PET imaging. Neuroimage. 2009;44:1334–1344. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantinescu CC, Mukherjee J. Performance evaluation of an Inveon PET preclinical scanner. Phys Med Biol. 2009;54:2885–2899. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/54/9/020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunder G, Siessmeier T, Piel M, Vernaleken I, Buchholz HG, Zhou Y, Hiemke C, Wong DF, Rosch F, Bartenstein P. Quantification of D2-like dopamine receptors in the human brain with 18F-desmethoxyfallypride. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:109–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito H, Hietala J, Blomqvist G, Halldin C, Farde L. Comparison of the transient equilibrium and continuous infusion method for quantitative PET analysis of [11C]raclopride binding. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1998;18:941–950. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199809000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulagowski JJ, Broughton HB, Curtis NR, Mawer IM, Ridgill MP, Baker R, Emms F, Freedman SB, Marwood R, Patel S, Patel S, Ragan CI, Leeson PD. 3-((4-(4-Chlorophenyl)piperazin-1-yl)-methyl)-1H-pyrrolo-2,3-b-pyridine: an antagonist with high affinity and selectivity for the human dopamine D4 receptor. J Med Chem. 1996;39:1941–1942. doi: 10.1021/jm9600712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammertsma AA, Hume SP. Simplified reference tissue model for PET receptor studies. Neuroimage. 1996;4:153–158. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1996.0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan J, Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Ding YS, Alexoff DL. Distribution volume ratios without blood sampling from graphical analysis of PET data. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 1996;16:834–840. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199609000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee J, Christian BT, Dunigan KA, Shi B, Narayanan TK, Satter M, Mantil J. Brain imaging of 18F-fallypride in normal volunteers: blood analysis, distribution, test-retest studies, and preliminary assessment of sensitivity to aging effects on dopamine D-2/D-3 receptors. Synapse. 2002;46:170–188. doi: 10.1002/syn.10128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee J, Christian BT, Narayanan T, Shi B. Measurement of d -amphetamine-induced effects on the binding of dopamine D-2/D-3 receptor radioligand, F-fallypride in extrastriatal brain regions in non-human primates using PET. Brain Res. 2005;1032:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee J, Yang ZY, Brown T, Roemer J, Cooper M. 18F-desmethoxyfallypride: a fluorine-18 labeled radiotracer with properties similar to carbon-11 raclopride for PET imaging studies of dopamine D2 receptors. Life Sci. 1996;59:669–678. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(96)00348-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee J, Yang ZY, Das MK, Brown T. Fluorinated benzamide neuroleptics--III. Development of (S)-N-[(1-allyl-2-pyrrolidinyl)methyl]-5-(3-[18F]fluoropropyl)-2, 3-dimethoxybenzamide as an improved dopamine D-2 receptor tracer. Nucl Med Biol. 1995;22:283–296. doi: 10.1016/0969-8051(94)00117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel VD, Lee DE, Alexoff DL, Dewey SL, Schiffer WK. Imaging dopamine release with Positron Emission Tomography (PET) and C-11-raclopride in freely moving animals. Neuroimage. 2008;41:1051–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.02.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Sidney: Academic Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Rominger A, Wagner E, Mille E, Boning G, Esmaeilzadeh M, Wangler B, Gildehaus FJ, Nowak S, Bruche A, Tatsch K, Bartenstein P, Cumming P. Endogenous competition against binding of [(18)F]DMFP and [(18)F]fallypride to dopamine D(2/3) receptors in brain of living mouse. Synapse. 2010b;64:313–322. doi: 10.1002/syn.20730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rominger A, Wagner E, Mille E, Boning G, Esmaeilzadeh M, Wangler B, Gildehaus FJ, Nowak S, Bruche A, Tatsch K, Bartenstein P, Cumming P. Endogenous competition against binding of [(18)F]DMFP and [(18)F]fallypride to dopamine D(2/3) receptors in brain of living mouse. Synapse. 2010a;64:313–322. doi: 10.1002/syn.20730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweinhardt P, Fransson P, Olson L, Spenger C, Andersson JL. A template for spatial normalisation of MR images of the rat brain. J Neurosci Methods. 2003;129:105–113. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(03)00192-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siessmeier T, Zhou Y, Buchholz HG, Landvogt C, Vernaleken I, Piel M, Schirrmacher R, Rosch F, Schreckenberger M, Wong DF, Cumming P, Grunder G, Bartenstein P. Parametric mapping of binding in human brain of D2 receptor ligands of different affinities. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:964–972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slifstein M. Revisiting an old issue: the discrepancy between tissue ratio-derived binding parameters and kinetic modeling-derived parameters after a bolus of the serotonin transporter radioligand 123I-ADAM. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:176–178. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.046631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slifstein M, Hwang DR, Huang Y, Guo N, Sudo Y, Narendran R, Talbot P, Laruelle M. In vivo affinity of [18F]fallypride for striatal and extrastriatal dopamine D2 receptors in nonhuman primates. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004a;175:274–286. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1830-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slifstein M, Narendran R, Hwang DR, Sudo Y, Talbot PS, Huang Y, Laruelle M. Effect of amphetamine on [(18)F]fallypride in vivo binding to D(2) receptors in striatal and extrastriatal regions of the primate brain: Single bolus and bolus plus constant infusion studies. Synapse. 2004b;54:46–63. doi: 10.1002/syn.20062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tantawy MN, Jones CK, Baldwin RM, Ansari MS, Conn PJ, Kessler RM, Peterson TE. [(18)F]Fallypride dopamine D2 receptor studies using delayed microPET scans and a modified Logan plot. Nucl Med Biol. 2009;36:931–940. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]