Abstract

Sample preparation, especially protein and peptide fractionation prior to identification by mass spectrometry (MS) are typically applied to reduce sample complexity. The second key element in this process is proteolytic digestion that is performed mostly by trypsin. Optimization of this step is an important factor in order to achieve both speed and better performance of proteomic analysis, and tryptic digestion prior to the MS analysis is topic of many studies. To date, only few studies pay attention on negative interaction between the proteolytic enzyme and sample components, and sample losses caused by these interactions. In this study, we demonstrated impaired activity after “in solution” tryptic digestion of plasma proteins caused by potent trypsin inhibitor family, inter-alpha inhibitor proteins. Sample boiling followed by gel electrophoretic separation and “in-gel” digestion drastically improved both number of identified proteins and the sequence coverage in subsequent LC-ESI-MS/MS. The presented investigations show that a thorough validation is necessary, when “in solution” digestion followed by LC-MS analysis of complex biological samples is performed. The parallel use of two or more different mass spectrometers can also yield additional information and contribute to further method validation.

1. Introduction

Protein digestion, mostly by trypsin, is one of very important factors in most proteomic investigations. It is also the reason that this step is the topic of many studies in order to optimize this analytical step. Chemical modification and immobilization of proteolytic enzymes, mostly onto porous beads [1], magnetic beads [2], or on monolithic supports [3], sometimes combined with both microwave or ultrasound-based reactors [4, 5] are the ways to optimize this step in proteomic analysis. Proteolysis of posttranslationally modified and hydrophobic proteins such as integral membrane proteins is an especially difficult task [6], and several special methods such as solubilzation with organic solvents and gel absorption-based sample preparation for tryptic digestion were developed [7, 8].

Further equally important step is the separation of tryptic peptides prior to LC-MS/MS. Mostly used separation methods in this step are 2D HPLC, mostly combination of strong cation-exchange (SCX) and reversed-phase (RP) HPLC, or electrophoretical methods such as isoelectric focusing and capillary electrophoresis. The first stage LC separation has the advantage over the electrophoretic methods because of good compatibility with the subsequent RP-LC-MS/MS for protein identification [9]. Consequently, a typical 2D chromatographic separation of tryptic peptides is followed by capillary or nano RP-LC hyphened with a mass spectrometry (MS or most frequently MS/MS) [9]. Again, optimization of these steps is the topic of many studies. Introduction of new chromatographic supports, especially for RP-HPLC that enables better recovery of hydrophobic and basic peptides is one of the important achievements on this field [10]. Use of medium or high pH mobile phases in RPLC separation of tryptic peptides is an optimization in order to further improve both separation and recovery of these peptides [11, 12]. It was shown that the use of volatile salt ammonium formate at medium or high pH as an alternative peptide separation method in RP mode, followed by low pH RPC significantly improves identification coverage, especially of hydrophobic and basic proteins [11,12]. Many studies pay special attention on mass spectrometric identification of hydrophobic and posttranslationally modified proteins, e.g. both glycoproteins and phosporylated proteins, such as integral membrane proteins that are commonly underrepresented in global large-scale proteomic studies [6, 7].

Because of the increasing availability of large genomics and proteomics databases and technological breakthroughs in last years, MS has become the preferred method for protein identification because of its high throughput and sensitivity [13, 14]. One of major tasks in proteomics is the biomarker discovery, and the further optimization of both MS and sample preparation methods towards high throughput analysis as an important development in direction of rapid detection and analysis of potential biomarker candidates. The most used samples for biomarker detection are body fluids, mostly plasma, serum and urine, tissue specimens and cell cultures [15]. In plasma, about 95% of proteins belong to high abundance group, and over 85% of them are two most abundant proteins serum albumin (SA) and IgG. These proteins can be removed by use of relatively expensive separation methods, mostly by immunoaffinity chromatography, and their depletion significantly facilitates analytical work towards detection of low-abundance proteins and biomarker discovery. Two most abundant proteins, SA and IgG can be simply removed by use of protein A (or protein G) affinity chromatography combined with anion-exchange chromatography [16]. This method is less costly intensive and enables an effective fractionation of plasma or serum proteins [15-17]. After removal of SA and IgG, other abundant proteins still remain in the sample, e.g. inter-alpha inhibitor proteins (IaIp). IaIp belong to a family of structure related serine protease inhibitors found in human plasma in relatively high concentrations (between 0.6 and 1.2 mg/mL). The complex structure of these proteins includes three heavy chains (HC 1, HC 2 and HC 3) with a molecular weight between 65 and 80 kDa, and a single 28-30 kDa light chain called bikunin. Bikunin is the only member of the IaIp that has protease inhibitory activity [18]. The IaIp chains are covalently bound via chondroitin sulfate. Because of their complex structure, IaIp form a broad peak in anion-exchange chromatography and their removal from the sample by use of chromatographic methods is relatively difficult [17].

To date, only few studies pay attention on interaction between the proteolytic enzyme and sample components, and possible sample losses caused by these interactions [19, 20]. In this study, we demonstrated impaired protein identification after “in-solution” tryptic digestion caused by potent trypsin inhibitor family, IaIp. Sample boiling followed by SDS-PAGE, and “in-gel” digestion drastically improved both number of identified proteins and the sequence coverage in subsequent LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sample

Human acute promyoelocytic leukemia cell line HL-60 CM American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) seeded at 105 cell/mL were grown in Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Media (IMDM, Gibco, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS, Gibco, Invitrogen) for 5 days. After centrifugation, the cell supernatant (80 mL) was dialyzed against 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, containing 10 mM NaCl (Buffer A) and applied to a 1 mL column packed with the diethylaminoethyl (DEAE) anion-exchange resin (Toyoscreen, Tosoh Bioscience, Stuttgart, Germany). The column was washed with Buffer A and stepwise eluted with 0.1 M, 0.2 M and 0.3 M NaCl in Buffer A (4 mL of each), and regenerated with 5 column volumes of 0.5 M NaOH. After regeneration, the column was washed with 10 mL H2O and equilibrated with 1 M Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4, and Buffer A (10 mL of each). Protein solution eluted with 0.2 M NaCl that contains components of interest was concentrated (20x) by spinning at 3,000 rpm (Amicon Ultra centrifugal filters, 30 kD cutoff, Millipore, Cork Ireland, and Eppendorf centrifuge 5804, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany), and used for further analyses.

2.2. SDS-PAGE

SDS-PAGE was performed in at least two independent experiments as described previously [17]. Shortly: before the electrophoretic separation, protein content in each sample was determined by use of bicinchoninic acid (BCA) Protein Assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) according to the manufacturer’s procedure. Protein samples containing between 5 and 20 μg protein/lane were solubilized in NuPAGE sample buffer (reducing or non-reducing) and heated at 100 °C for 5 minutes. The electrophoretic separation was performed with precast 4-12% Bis-Tris gels in a Xcell Sure Lock Mini Cell (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s procedure. The gels were stained with GelCodeBlue (Pierce) and visualized by a VersaDoc Imaging System (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA) before excising the bands for in-gel digestion.

2.3. “In-gel” digestion procedure

The gel bands were excised by extracting 6-10 gel particles with glass Pasteur pipettes. Sample preparation including protein alkylation before proteolytic digestion was performed as previously described [21]. After alkylation, the solution was removed and the gel peaces washed and dried. After rehydratation for 15 minutes at 4 °C in digestion buffer consisting of 0.05 M ammonium bicarbonate, 5 mM CaCl2 and 12.5 μg/mL trypsin (porcine, sequence grade, Promega, Madison, WI, USA), the proteins were digested. After allowing the gel plugs to swell for 15 minutes, an additional volume of digestion buffer was added to cover the gel plugs that had completely adsorbed all initially added buffer, and the samples were then placed for 16 hours in an incubator set at 37 °C. After digestion, the peptides were recovered from the mixture by centrifugation (Eppendorf centrifuge). Peptides remaining in the gel were extracted with a solution of 50% (v/v) acetonitrile containing 1% (v/v) trifloroacetic acid (TFA) (Pierce) in 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate for 10 min with shaking and subsequently pooled with the first fraction. The tryptic digest was held at − 80 °C until ready for LC-MS/MS analysis.

2.4. Digestion of whole fractions separated by anion-exchange chromatography (“in-solution” digestion)

Aliquots from separated fractions containing about 50 μg protein each eluted from the anion-exchange column were precipitated with the RedyPrep 2-D Cleanup kit (BioRad) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Denatured protein pellets were redissolved with 20 μL of 0.5 M triethyl ammonium bicarbonate, pH 8.5, and reduced, alkylated and tryptically digested according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). After digestion, the tryptic peptides were dried in a vacuum centrifuge (Vacufuge, Eppendorf). The material was twice resuspended with water and dried, and subsequently twice redissolved in a solution containing 0.5% (v/v) formic acid and 20% acetonitrile, and thereafter vacuum dried. After resuspending in the same solvent and controlling the pH value, the peptides were isolated using a strong cation-exchange TipTop™ (polyLC Inc., Columbia, MD, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The ammonium formate eluates were dried and redissolved in formic acid:water:acetonitrile:TFA mixture (0.1:95:5:0.01) in preparation for the LC-MS/MS analysis.

2.5. Identification of proteins with LC-MS/MS

Tryptic “in-gel” or “in-solution” digests were separated with an RP column (C-18 PepMap 100, LC Packings/Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) as previously described [22]. Two different gradients were used. The first one was starting with 5% (v/v) acetonitrile in 0.1% (v/v) formic acid to 35% acetonitrile in formic acid (solvent B) for 75 minutes. Alternatively, a very shallow gradient was used starting with 5% and ending with 35% solvent B in 4 hr. For “in-gel” digested samples, only the 75 min gradient was used, and for “in-solution” digested samples both 75 min and 4 hr gradients were applied. The column eluate was introduced directly onto a QSTAR XL mass spectrometer (Sciex and Applied Biosystems, Concord, Ontario, Canada) via ESI. Candidate ion selection, fragmentation and data collection were performed as follows: Candidate ions were selected and fragmented using a standard information dependent acquisition (IDA) method. Half-second “MS” scans (range between 300 and 1500 Thompson, Thompson (Th) = MW/z) were used to identify candidates for fragmentation during the 5 subsequent “MS/MS” scans (1.5s; range between 65 and 1500 Th). A candidate for fragmentation has to be assigned a charge in the range of +2 to +4. In order to allow more thorough exploration of chromatographic peaks containing simultaneously eluting peptides, ions whose fragmentation spectrum had just been collected were dynamically excluded for 40s from being a candidate.

Protein identifications were performed with ProteinPilot software (Sciex and Applied Biosystems), using a human “RefSeq” databases from NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nim.nih.gov/RefSeq/). This software is the successor of ProID and ProGroup, and uses the same scoring method [17]. Briefly, given a protein score S, the likehood that the protein assignment is incorrect is 10−S, and the scores above 2.0 require that at least two sequence-independent peptides be identified. Protein identification was performed in, at least, two independent experiments.

In parallel experiments, tryptic peptides were separated on a 12 cm × 75 μm I.D. C18 column (Column Engineering, Ontario, CA, USA), containing an integrated ~4 μm ESI emitter tip. Peptides were eluted using a linear gradient starting with 100% solvent A (0.1 M acetic acid in water) to 70% solvent B (acetonitrile) over 30 minutes (Agilent Technologies, Paolo Alto, CA, USA). Peak parking during the time when peptides were expected was accomplished by 10 times reducing the flow rate (from 200 nL/min to ~20 nL/min). Eluting peptides were introduced onto a LTQ linear ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron Corporation, San Jose, CA, USA) with a 1.9 kV electrospray voltage. Full MS scans in the m/z range of 400-1800 were followed by data independent acquisition of spectra for the five most abundant ions, using a 30-s dynamic exclusion time. Protein identification was performed in two independent experiments.

Database searching was performed using the peak lists in the SEQEST program [23]. The precursor-ion tolerance was 2.0 Da and the fragment ion tolerance was 0.8 Da. Enzymatic digestion was specified as trypsin, with up to 2 missed cleavages allowed. The search contains sequences identified as human or bovine in NCBI’s nr database (November, 2006), which was created using FASTA filtering tools found in BioWorks (Thermo). A list of reversed-sequences was created from these entries and appended to them for database searching so that false positive rates could be estimated [24].

3. Results and discussion

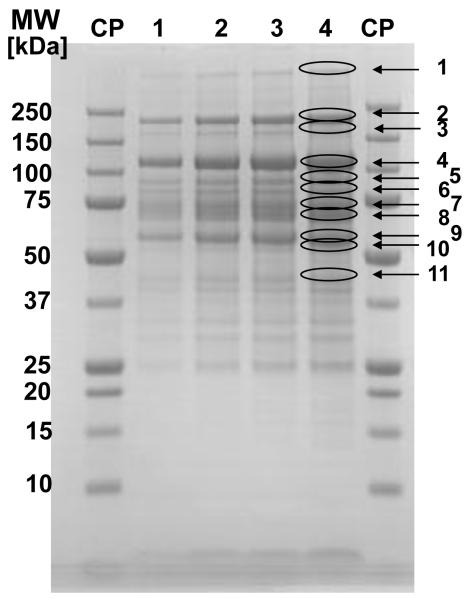

In order to identify secreted proteins, the supernatant of the human acute promyoelolytic cell line HL-60 CM grown for 5 days in a media containing 10% FCS was pre-fractionated by use anion-exchange chromatography. The fraction eluted by 0.2 M NaCl in Buffer A was further analyzed in order to identify secreted proteins of interest. The protein mixture was further digested by trypsin. The method for tryptic digestion (“in-solution” digestion) is routinely used, and results comparable to the time-consuming SDS-PAGE or 2D electrophoretic separations followed by “in-gel” digestion were achieved [17]. However, in the present investigation only 16 proteins were identified by use of the standard method for protein identification by LC-ESI-MS/MS and a 75 min gradient for peptide separations in nano-HPLC, prior to ESI-MS/MS analysis (see Tables 1 and 2 and Materials and methods). The SDS-PAGE separations of these proteins are shown in Figures 1 and 2. The result of SDS-PAGE separation of mixtures with increasing protein amount (5, 10, 15 and 20 μg, lanes 1-4) separated under reducing conditions is shown in Figure 1. The same mixtures were separated under non-reducing conditions (see Figure 2). As shown in both Figures, this fraction contains much more than 16 polypeptide bands, and it can be expected that in many bands more than 1 protein will be identified [17, 22]. Under these circumstances, the use of a shallow gradient usually yields in identification of more proteins [17, 22]. However, if the gradient time was extended to 4 hours, only 6 additional proteins were identified (see Tables 1 and 2). The sample containing “in solution” digested peptides from the same protein mixture was subsequently analyzed by a different LC-ESI-MS/MS system (Agilent – LTQ linear ion trap mass spectrometer, Thermo Electron Corporation, see Materials and methods), and again, only 23 proteins were identified (see Table 1 and 2). If this LC-ESI-MS/MS system was used, some additional proteins, some of them low abundance ones such as clotting factor IX, cartilage oligomeric protein and lumican were identified. On the other hand, this system failed to identify some relatively abundant protein such as carboxypeptidase N and HMW kininogen 1 (see Table 1). Pregnancy zone protein and CD 44 were also not identified, and this information would have been lost, if only this system was used (see Table 1).

Table 1.

List of identified proteins after “in solution” and “in gel” digestion

| No. | Protein name | Accession No. |

In sol. 75 min. grad1 |

In sol. 4 hr grad2 |

In sol. MS II3 |

In gel4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | ITI H1 chain | 292530 | + | + | + | + |

| 2. | ITI H2 Chain | 645038 | + | + | + | + |

| 3. | ITI H3 Chain | 876950 | + | + | + | + |

| 4. | Fibronectin | 855785 | + | + | + | + |

| 5. | Heparin Cofactor2 | 879573 | + | + | − | + |

| 6. | Serum albumin | 745872 | + | + | + | + |

| 7. | C4A isoform b | 292950 | + | + | + | + |

| 8. | Alpha 2 HS glycoprotein | 953689 | + | + | + | + |

| 9. | Fibulin 1 | 218803 | + | + | + | + |

| 10. | Vitronectin | 298971 | + | + | + | + |

| 11. | Carboxypeptidase N | 10295 | + | + | − | + |

| 12. | Pregnancy zone protein | 25426 | + | + | − | + |

| 13. | Apolipoprotein A1 | 853525 | + | + | − | + |

| 14. | CD 44 antigen | 955768 | + | + | − | + |

| 15. | HMW Kininogen −1 | 32328 | + | + | − | + |

| 16. | 29 kDa protein | 795830 | + | + | − | + |

| 17. | Complement C3 | 783987 | − | + | + | + |

| 18. | Complement C4B | 654875 | − | + | + | + |

| 19. | Thrombospondin 4 | 328550 | − | + | + | + |

| 20. | Prothrombin | 19568 | − | + | + | + |

| 21. | Gelsolin | 646773 | − | + | + | + |

| 22. | Alpha-2-antiplasmin | 879608 | − | + | + | − |

| 23. | Alpha-2-macroglobulin | 478003 | − | − | + | + |

| 24. | 263 kDa protein | 873210 | − | − | − | + |

| 25. | Hemoglobin | 796636 | − | − | − | + |

| 26. | Clotting Factor IX | 11767596 | − | − | + | + |

| 27. | Actin, cytoplasmic 1 | 21439 | − | − | + | + |

| 28. | Osteonectin | 14572 | − | − | + | + |

| 29. | Apolipoprotein B-100 | 22229 | − | − | + | + |

| 30. | IgG | 884107 | − | − | − | + |

| 31. | HSP 90 alpha, isoform 1 | 784295 | − | − | − | + |

| 32. | HSP 90 alpha Isoform 2 | 382470 | − | − | − | + |

| 33. | HSP 90 beta | 414676 | − | − | − | + |

| 34. | HSP89-alpha-delta-N | 604607 | − | − | − | + |

| 35. | Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein |

28030 | − | − | + | + |

| 36. | Antitrombin III | 32179 | − | − | − | + |

| 37. | Periostin | 218585 | − | − | − | + |

| 38. | TGFBI – Transforming GF beta ind. protein |

292950 | − | − | − | + |

| 39. | ASHG 29 kDa protein | 795830 | − | − | − | + |

| 40. | Vitamin D binding prot. | 555812 | − | − | − | + |

| 41. | Tubulin alpha | 930688 | − | − | − | + |

| 42. | Tubulin beta | 645452 | − | − | − | + |

| 43. | PSMA 7, subunit alpha | 218372 | − | − | − | + |

| 44. | YWHAE 22 kDa protein | 793344 | − | − | − | + |

| 45. | F5 252 kDa protein | 22937 | − | − | − | + |

| 46. | Protein S | 294004 | − | − | − | + |

| 47. | Coagulation factor X | 19576 | − | − | − | + |

| 48. | Apolipoprotein C3 | 28748 | − | − | + | − |

| 49. | Lumican | 51884 | − | − | + | − |

“In solution” digestion, 75 min gradient, LC Packings/Sciex-Applied Biosystems LC-MS/MS (see Materials and methods).

“In solution” digestion, 4 hrs gradient, LC Packings/Sciex-Applied Biosystems LC-MS/MS (see Materials and methods).

“In solution” digestion, Agilent Technologies-Thermo Electron Corporation LC-MS/MS (see Materials and methods).

“In gel” digestion, 75 min gradient, LC Packings/Sciex-Applied Biosystems LC-MS/MS (see Materials and methods).

Table 2.

For identification of the used methods (columns 1-4) see the legend in Table 1

| Number of proteins identified | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| In sol. 75 min. grad1 | In sol. 4 hr grad2 | In sol. MS II 3 | In gel4 |

| 16 | 22 | 22 | 46 |

Figure 1.

SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions of investigated protein mixture (Fraction 2 after anion-exchange chromatography, see Materials and methods). The excised bands that are taken for “in gel” tryptic digestion and further analysis by LC-ESI-MS/MS are labeled by the numbers of bands (see lane 4)

CP – calibration proteins

Lane 1 – 5 μg protein was applied

Lane 1 – 10 μg protein was applied

Lane 1 – 15 μg protein was applied

Lane 1 – 20 μg protein was applied, and separated proteins from this lane were excised and further analyzed by LC-ESI-MS/MS.

Figure 2.

SDS-PAGE under non-reducing conditions of investigated protein mixture (Fraction 2 after anion-exchange chromatography, see Materials and methods). For further information see Figure 1.

As shown in Tables 1 and 2, 46 proteins could be identified, if the sample was previously separated by SDS-PAGE under reducing and non-reducing conditions and the excised bands were “in gel” digested by trypsin and proteins identified by nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS. As mentioned above, this result was somewhat surprising, because a comparable number of proteins were identified, if “in gel” digestion and “in solution” digestion, followed by a shallow gradient were compared [17]. However, in the present case, some important information would be missing, if only “in solution” digestion was used. Heat shock proteins HSP 90 alpha and beta and HSP89-alpha-delta-N as well as periostin and transforming growth factor beta induced protein (TGFBI) were identified after separation by SDS-PAGE and “in-gel” digestion. These proteins have a possible function in malignant modifications and metabolic functions of malignantly transformed cells and can be eventually used as biomarker candidates [22, 25-27]. On the other hand, the identifications of lumican and apolipoprotein C3 were missed. These proteins were identified by the second mass spectrometer (LTQ, Thermo Electron Corp., see Table 1 and Materials and methods). These two proteins may be missed, when the samples for “in gel” digestion were excised. The incomplete protein recovery from the gel is one of potential pitfalls, if “targeted” sample extraction is performed (see Figures 1 and 2).

The extreme discrepancy between the “in gel” and “in solution” digestion is somehow puzzling and can be only explained by inhibition of trypsin by a potent protease(s). As shown in Figures 1 and 2, the analyzed sample contains a significant amount of IaIp, and the bands corresponding to these proteins can be clearly seen, the first one with an apparent molecular weight of 225 kDa (inter-alpha inhibitor) and the second at 125 kDa (pre-alpha inhibitor; both in lanes 1 and 2 in Figures 1 and 2). Both IaI and pre-alpha inhibitor were also identified by mass spectrometry (bands 2 and 4 in Fig. 1, and bands 3 and 6 in Fig. 2). In bands with an apparent MW of 225 kDa, both heavy chains H1 and H2 of IaIp were identified. In bands with an apparent MW of 125 kDa, both heavy chains H2 and H3 were detected (for IaIp identification, see Ref. [18]). We failed to detect bikunin in either IaI or pre-alpha inhibitor. Interactions between protease inhibitors and the proteolytic enzymes used for digestion (mainly trypsin) can usually be prevented by sample treatment. It seems that we failed to prevent this inhibition with the sample in the present experiment. Further indication that IaIp have bound to trypsin by their inhibitory subunit is that in all experiments bikunin was not identified (see Table 1). Bikunin is the inhibitory active chain in the IaIp molecule, and together with HC1, HC2 and HC3, it was always identified in samples that contained significant amounts of this protein family. However, we have never had such problems when protein mixtures containing IaIp were analyzed by “in solution” digestion followed by LC-MS/MS (see Tables 1 and 2 and References [15, 17, 19]). In the present investigation, where a cell supernatant was analyzed, the balance between protease inhibitors and proteases is disturbed. This may be the reason for the inhibitory activity of these proteins and, as a consequence, for the low yield of detected proteins.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

4. References

- [1].Freije JR, Mulder PP, Werkman W, Rieux L, Niederlander HA, Verpoorte E, Bischoff R. Chemically modified, immobilized trypsin reactor with improved digestion efficiency. J Proteome Res. 2005;4:1805–1813. doi: 10.1021/pr050142y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Karbassi ID, Nyalwidhe JO, Wilkins CE, Cazares LH, Lance RS, Semmes OJ, Drake RR. Proteomic expression profiling and identification of serum proteins using immobilized trypsin beads with MALDI-TOF/TOF. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:4182–4192. doi: 10.1021/pr800836c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Calleri E, Temporini C, Perani E, De Palma A, Lubda D, Mellerio G, et al. Trypsin-based monolithic bioreactor coupled on-line with LC/MS/MS system for protein digestion and variant identification in standard solutions and serum samples. J Proteome Res. 2005;4:481–490. doi: 10.1021/pr049796h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lopez-Ferrer D, Capelo JL, Vázquez J. Ultra fast trypsin digestion of proteins by high intensity focused ultrasound. J Proteome Res. 2005;4:1569–1574. doi: 10.1021/pr050112v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lin S, Yun D, Qi D, Deng C, Li Y, Zhang X. Novel microwave-assisted digestion by trypsin-immobilized magnetic nanoparticles for proteomic analysis. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:1297–1307. doi: 10.1021/pr700586j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Helbig AO, Heck AJ, Slijper M. Exploring the membrane proteome – challenges and analytical strategies. J Proteomics. 2010;10:868–878. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Blonder J, Chan KC, Issaq HJ, Veenstra TD. Identification of membrane proteins from mammalian cell/tissue using methanol-facilitated solubilization and tryptic digestion coupled with 2D-LC-MS/MS. Nature Protocols. 2006;1:2784–2790. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lu X, Zhu H. Tube-gel digestion: a novel proteomic approach for high throughput analysis of membrane proteins. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:1948–1958. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500138-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Motoyama A, Yates JR. Multidimensional LC separations in shotgun proteomics. Anal Chem. 2008;80:7187–7193. doi: 10.1021/ac8013669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Martosella J, Zolotarjova N, Liu H, Moyer SC, Perkins PD, Boyes BE. High recovery HPLC separation of lipid rafts for membrane proteome analysis. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:1301–1312. doi: 10.1021/pr060051g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Gilar M, Olivova P, Daly AE, Gebler JC. Ortogonality of separation in two-dimensional liquid chromatography. Anal Chem. 2005;77:6426–6434. doi: 10.1021/ac050923i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Yang Y, Boysen RI, Harris SJ, Hearn MT. Peptide mapping with mobile phase of intermediate pH value using capillary reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 2009;1216:3767–3773. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2009.02.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Fournier J-P, Gilmore JM, Martin-Brown SA, Washburn MP. Multidimensional separation-based shotgun proteomics. Chem Rev. 2007;107:3654–3686. doi: 10.1021/cr068279a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lambert JP, Ethier M, Smith JC, Figeys D. Proteomics: From gel based to gel free. Anal Chem. 2005;77:3771–3788. doi: 10.1021/ac050586d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kovac S, Yang X, Huang F, Hixson D, Josic Dj. Proteomics as a tool for optimization of human plasma protein separation. J Chromatogr A. 2008;1194:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2008.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Cerk Petric T, Brne P, Gabor B, Govednik L, Barut M, Strancar A, Zupancic Kralj L. Anion-exchange chromatography using short monolithic columns as a complementary technique for human serum albumin depliton prior to human plasma proteome analysis. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2007;43:243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2006.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Yang X, Clifton J, Huang F, Kovac S, Hixson DC, Josic Dj. Proteomic analyses for process development and control of therapeutic protein separation from human plasma. Electrophoresis. 2009;30:1185–1193. doi: 10.1002/elps.200800501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Josic Dj, Brown MK, Huang F, Lim Y-P, Rucevic M, Clifton JG, Hixson DC. Proteomic characterization of inter-alpha inhibitor proteins from human plasma. Proteomics. 2006;6:2874–2885. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Stewart II, Thompson T, Figeys D. 18O labeling: a tool for proteomics. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2001;15:2456–2465. doi: 10.1002/rcm.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Sevinsky JR, Brown KJ, Cargile BJ, Bundy JL, Stephenson JL., Jr Minimizing back exchange of 18O/16O quantitative proteomics experiments by incorporation of immobilized trypsin into the initial digestion step. Anal Chem. 2007;79:2158–2162. doi: 10.1021/ac0620819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Josic Dj, Brown MK, Huang F, Callanan H, Rucevic M, Nicoletti A, Clifton J, Hixson DC. Use of selective extraction and fast chromatographic separation combined with electrophoretic methods for mapping of membrane proteins. Electrophoresis. 2005;26:2809–2922. doi: 10.1002/elps.200500060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Clifton JG, Li X, Reutter W, Hixson DC, Josic Dj. Comparative proteomics of rat liver and Morris hepatoma 7777 plasma membranes. J Chromatogr B. 2007;849:293–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Eng JK, McCormack AL, Yates JR., III An approach to correlate tandem mass spectral data of peptides with amino acid sequences in a protein database. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1994;5:976–989. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(94)80016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Elias JE, Gygi SP. Target-decoy search strategy for increased confidence in large-scale protein identification by mass spectrometry. Nature Methods. 2007;4:207–214. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Mills DR, Haskell MD, Callanan HM, Flanagan DL, Brilliant K, Yang DQ, Hixson DC. Monoclonal antibody to novel cell surface epitope on Hsc70 promotes morphogenesis of bile ducts in newborn rat liver. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2010;15:39–53. doi: 10.1007/s12192-009-0120-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Siriwardena BSMS, Kudo Y, Ogawa I, Kitigawa M, Kitijama S, Hatano H, et al. Periostin is frequently overexpressed and enhances invasion and angiogenesis in oral cancer. Brit J Cancer. 2006;95:1396–1403. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Munier FL, Korvatska E, Djemaï A, Le Paslier D, Zografos L, Pescia G, Schorderet DF. Kerato-epithelin mutations in four 5q31-linked corneal dystrophies. Nature Genet. 1997 March;15:247–51. doi: 10.1038/ng0397-247. 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]