Maternal cocaine abuse during pregnancy has been correlated with a greater incidence of maternal neglect and problems with maternal-infant bonding.1 Children of mothers who have abused cocaine during pregnancy have exhibited signs of increased irritability and altered state liability as newborns2,3 and are aggressive, show poor social attachment, and display abnormal play behavior in unstructured environments as young children.4 These data suggest cocaine-induced, abnormal development of socioemotional behavior, but it is difficult to determine if these deficits are a direct result of cocaine or are related to living in an unstable or abusive environment.

Animal research on the effects of prenatal cocaine exposure suggest that offspring exposed prenatally to cocaine exhibit signs of behavioral abnormalities including increased “emotionality” and neophobia5,6 and aggression towards an intruder or other untreated conspecifics.7–9 Long-term changes in specific neurotransmitter systems may be related to behavioral alterations.

On the basis of previous findings,7–9 we focused our research on cocaine-induced alterations of both maternal and offspring social/aggressive behavior. The following data include a summary of results from several recent experiments.

METHODS

Treatment Groups

Dams received 15 mg/kg of cocaine-HCL (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Missouri) in a saline solution (CC) or an equal volume of (0.9%) normal saline (Sal) twice daily at approximately 9:00 AM and 4:00 PM from gestational days 1–20. An intermittent cocaine group received the same dose of cocaine on 2 consecutive days every 4 days throughout gestation (days 2–3, 8–9,14–15, and 19–20), and the amfonelic acid-treated (AFA, a selective dopamine uptake inhibitor) dams received 1.5 mg/kg of AFA dissolved in a pH 10 solution (Sterling Winthrop Labs, Rensselaer, New York) once daily (9:00 AM) on gestational days 1–20.

Procedure

Treatment dams were either yoke fed or fed ad libitum, were weighed daily, and had their daily food consumption measured. Dams were tested on postpartum days 6, 8, and 10 for aggression towards an intruder during a 10-minute period. On postpartum days 8 or 11, dams were killed and the ventral tegmental area, hippocampus, and amygdala were removed for oxytocin radioimmunoassay. Details of aggression testing procedures were published elsewhere.10 Pups were placed with surrogates immediately after birth, weaned at 21 days of age, and separated into same sex groups of three for behavioral testing on postnatal days 30, 60, 90, and 180. Pups from three of the test periods (30, 60, and 180 days) were used for HPLC analyses of monoamines, and several pups were killed on postnatal days 1, 4, and 10 for assessment of 5-HT1A receptor development using immunobinding assays (using a specific 5-HT1A antipeptide antibody, which was a gift of John Raymond) and quantitative, competitive RT-PCR using internal standards. Frequency, duration, and latency of behaviors were recorded using a computer program (Behavior L.W.M.). Behaviors were usually videotaped and analyzed by two independent observers. Statistical analyses included factor analyses, Fisher’s exact test, and analyses of variance.

RESULTS

Data on maternal indices, neonatal development, and other behavioral testing were previously reported.11

Maternal Aggression

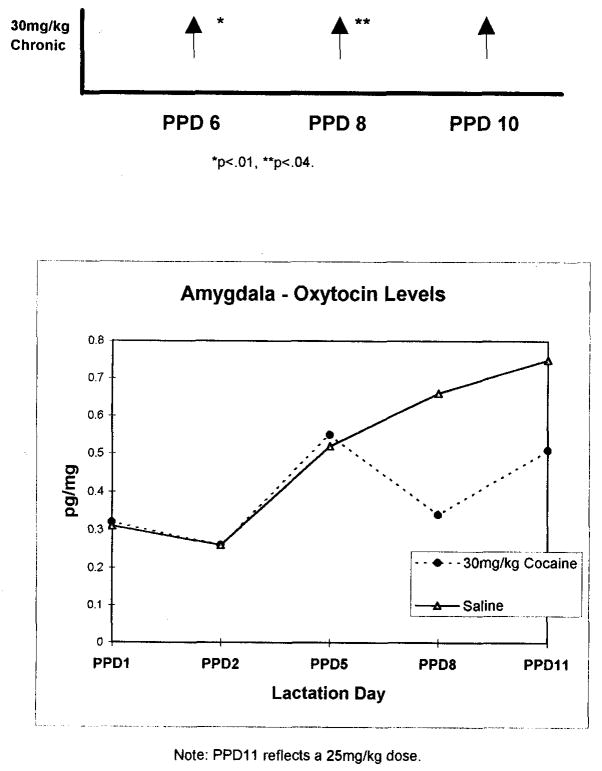

Data for maternal aggression and oxytocin levels are summarized in Figure 1. Aggression towards an intruder was significantly increased in CC-treated dams on postpartum days 6, 8, and 10. Oxytocin was also reduced in the amygdala of the CC-treated dams relative to Sal- and AFA-treated dams, indicating more than a dopaminergic action of cocaine on aggression. (Intermittent cocaine-treated dams were not tested for maternal behavior.) Although dopamine-related behaviors (locomotor, rearing) were increased in the AFA-treated dams (relative to Sal- and CC-treated dams), they were not as aggressive as CC- or even Sal-treated dams, and they also had the highest levels of oxytocin in the amygdala of all groups.

FIGURE 1.

Maternal aggression fight attacks relative to saline controls.

Offspring Behavior

Abnormalities were age, sex, and task specific, as shown in Table 1. Cocaine-exposed pups show evidence of altered activity, social behavior, and aggression towards conspecifics which appears to occur in a developmental pattern with CC treatment having a stronger behavioral effect than intermittent cocaine. Serotonin and 5-HIAA levels were lower at postnatal day 60 in the striatum and hippocampus and in the striatum and amygdala at postnatal day 180.12 Expression of 5-HT1A receptors was increased in the brain overall at postnatal day 1, began to return to normal at postnatal day 4, and was significantly decreased in the brain overall at postnatal day 10 in male CC-exposed pups. Offspring prenatally exposed to the dopamine uptake inhibitor AFA were the most aggressive of all offspring followed by CC, intermittent cocaine, and Sal-treated rats, respectively. These data indicate a predominant dopaminergic effect on aggression in offspring. Aggression was decreased in all offspring groups by pretreatment with the anxiolytic gepirone, a 5-HT1A partial agonist, although the AFA-treated pups were least affected by gepirone, and aggression was still evident in the CC-treated pups, even after gepirone treatment. These data suggest that both dopaminergic and serotonergic systems as well as stress-related effects are probably involved in cocaine-induced aggression in prenatally exposed offspring.

TABLE 1.

Behavioral Effects on Offspring after Prenatal Cocaine Exposure

| PND30 | PND60 | PND90 | PND 180 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic cocaine | Males: hypoactivity first 15 minutes of 6-hour activity test | Males: neophobic, did not enter open field in 1st 5 min. Female: spent more time rough grooming a conspecific, p <0.05 and took longer to allow contact, ns |

Males: took longer to reciprocate contact, p <0.02. Males: spent more time rough grooming a conspecific, ns | Neophobic, males chased an intruder more often, p <0.01, for a longer time, p <0.01 & sooner, p <0.01. Male intruders were threatened longer, p <0.05. Females made more vocalizations, for a longer time in response to fewer airpuffs. Males took more trials to habituate responding to air puff (40% of baseline), p <0.05. Following plus maze exposure, males decreased ACTH levels at 0 & 90 min, p<0.05. Females decreased ACTH at 90 min, ns males decreased ACTH after exposure to an unfamiliar male, p <0.05 |

| Intermittent cocaine | Males-hypoactive during 3-hour dark phase of 6-hour activity test | Hyperactive in the open field, p <0.01. Turned right on entrance, p <0.05, spent more time in section 1 and less time in start box, p <0.05. General decrease in activity, ns | N/A | |

| Amfonelic acid | ns | Hypoactive during dark cycle, p <0.05. Spent more time in section 1 & less time in start box, p <.05. | N/A | Escaped an intruder faster, p <0.05 Spent more time being aggressive towards an intruder (piloerection, aggressive posture, fight attack), following gepirone, p <0.01. |

| Saline | ns | ns | ns | Took longer to escape intruder in Session 1 than Session 2. Females-required more air puffs to vocalize, vocalized less and for less time than males, p <0.05. |

Our results suggest that both maternal and offspring social/aggressive behavior are altered by CC treatment and that dopaminergic, serotonergic, and oxytocinergic (dams) systems probably mediate these effects. On the basis of these findings we hypothesized that changes in brain hormonal or neurochemical activity, as a result of chronic cocaine treatment (30 mg/kg) or prenatal exposure to chronic gestational cocaine treatment, alters the sensory or perceptual systems of both mothers and offspring so that, unlike untreated animals, they view stimuli as more threatening than they really are and react to a perceived threat in an abnormally aggressive manner.

Acknowledgments

Assistance with the assays was provided by the Mental Health Clinical Research Center of the Psychiatry Department #MH33127.

Footnotes

These studies were supported in part by the National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant R29-DA08456-01 (to J.M.J.) and the UNC Neurosciences Center.

References

- 1.Burns KA, Chethik WJ, Burns WA, Clark R. Dyadic disturbances in cocaine-abusing mothers and their infants. J Clin Psychol. 1991;313:666–669. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199103)47:2<316::aid-jclp2270470220>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chasnoff IJ, Burns KA, Burns WJ. Cocaine use in pregnancy: Perinatal morbidity and mortality. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1987;9:291–293. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(87)90017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chasnoff IJ, Burns WJ, Schnoll SH, Burns KA. Cocaine use in pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:666–669. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198509123131105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howard J, Beckwith L, Rodnig C, Kropenske V. The development of young children of substance-abusing parents: Insights from seven years of intervention and research. Zero to Three. 1989;9:8–12. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Church MW, Overbeck GW. Prenatal cocaine exposure in the Long Evans rat. II. Dose-dependent effects on offspring behavior. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1990;12:327–334. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(90)90052-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johns JM, Means MJ, Anderson DR, Bass EW, Means LW, McMillen BA. Prenatal exposure to cocaine. II. Effects on open field activity and cognitive behavior in Sprague-Dawley rats. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1992;14:343–349. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(92)90041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johns JM, Means LW, Bass EW, Means MJ, Zimmerman LI, McMillen BA. Prenatal exposure to cocaine: Effects on aggression in Sprague-Dawley rats. Dev Psychobiol. 1994;27(2):27–239. doi: 10.1002/dev.420270405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodwin GA, Heyser CJ, Moody CA, Rajachandran L, Molina VA, Arnold HM, McKinzie DL, Spear NE, Spear LP. A fostering study of the effects of prenatal cocaine exposure. II. Offspring behavioral measures. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1992;14:423–432. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(92)90053-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noonan LR, Johns JM. Prenatal cocaine exposure affects social behavior in Sprague-Dawley rats. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1995;17:569–576. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(95)00017-l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johns JM, Noonan LR, Zimmerman LI, Li L, Pedersen CA. Effects of chronic and acute cocaine treatment on the onset of maternal behavior and aggression in Sprague-Dawley rats. Behav Neurosci. 1994;108:1–7. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.108.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johns JM, Means MJ, Means LW, McMillen BA. Prenatal exposure to cocaine. I. Effects on gestation, development and activity in Sprague-Dawley rats. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1992;14:337–342. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(92)90040-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henderson MG, McMillen BA. Changes in dopamine, serotonin and their metabolites in discrete brain areas of rat offspring after in utero exposure to cocaine or related drugs. Teratology. 1993;48:421–130. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420480506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]