Abstract

The paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN) is a major regulator of stress responses via release of Corticotropin Releasing Hormone (CRH) to the pituitary gland. Dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is characteristic of individuals with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). Postmortem data from individuals diagnosed with MDD show increased levels of CRH mRNA and CRH immunoreactive neurons in the PVN. In the current study, an immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis revealed increased levels of CRH in the PVN of newborn mice lacking functional GABAB receptors. There was no difference in the total number of CRH immunoreactive cells. By contrast, there was a significant increase in the amount of CRH immunoreactivity per cell. Interestingly, this increase in CRH levels in the GABAB receptor R1 subunit knockout was limited to the rostral PVN. While GABAergic regulation of the HPA axis has been previously reported in adult animals, this study provides evidence of region-specific GABA modulation of immunoreactive CRH in newborns.

Keywords: Corticotropin Releasing Hormone, Paraventricular Nucleus, GABA, Hypothalamic Pituitary Adrenal Axis, Development, Pituitary, Nuclear Compartments

I. Introduction

The hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis is a major neuroendocrine component of physiological stress responses. Upon perception of a threatening or stressful environment, neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN) release the peptide hormone corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH). CRH then acts on cells in the anterior pituitary to cause the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which stimulates the production and release of glucocorticoids from the adrenal gland (reviewed in 1, 2). An acutely elevated level of cortisol is beneficial due to the mobilization of energy stores and the creation of a heightened state of alertness. However, prolonged periods of increased HPA axis activity is detrimental to the organism and associated with major depressive disorder and anxiety related disorders in humans (3). Both anxiety (4,5) and depression (6,7) are more prevalent in females than males. As the PVN is pivotal for HPA axis function and the integrator of threat, hormone, cognitive, and emotional information (8) the regulation of its output is critical. Based on post mortem studies, humans with depression have more CRH immunoreactive neurons in the PVN and increased levels of CRH mRNA (9,10).

Gamma aminobutyric Acid (GABA) is the predominant inhibitory neurotransmitter in the adult brain. There is mounting evidence to implicate GABA in anxiety and depression related disorders via signaling through GABAA and GABAB receptors (11, 12). GABAA receptors are pentameric ligand gated chloride channels and the targets of anxiolytic drugs like the benzodiazepines. GABAB receptors are heterodimeric G protein coupled receptors that are rendered non-functional by removal of either subunit (13) and are also the targets of drugs thought to have anxiolytic activity (e.g., baclofen; 14). The current study took advantage of mice with a genetic disruption of the R1 subunit of the GABAB receptor that eliminates functional activity. Previous studies suggested that decreased GABAB receptor signaling during development altered the cytoarchitecture of the hypothalamus including the PVN (15, 16). In mice lacking functional GABAB receptors there were significant alterations in the locations of cells in or around the PVN containing immunoreactive estrogen receptor α and neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) fibers, as well as decreased levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) immunoreactivity (16). In the course of investigating the role of GABAB receptor signaling in the placement of CRH neurons in the developing PVN there was a notable increase in the strength of CRH immunoreactivity in female GABAB R1 subunit knockout mice compared to wild type littermates. The current study, using a semi-quantitative immunohistochemical approach, was conducted to directly test whether GABAB receptor signaling regulates the levels of CRH immunoreactivity in the developing female PVN.

II. Materials and Methods

II.i. Animals

This study used a transgenic line of mice lacking functional GABAB receptors (15, 16). Mice with disruption of GABAB receptor signaling were generated on a C57BL/6 background through the insertion of a gene encoding β-galactosidase in the coding region of the R1 subunit of the GABAB receptor (13). Heterozygous breeding pairs were used to generate homozygous null, heterozygous, and wild-type animals to be used in immunohistochemical studies. Animals were mated overnight and checked for vaginal plugs the following morning. The day that plugs were found was designated as embryonic day (E) 0. Pups were transcardially perfused on E13, E15, or postnatal day (P) 0. Pregnant mice were anesthetized with ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (8 mg/kg), and embryos were removed individually before perfusion with 2 ml (E13 and E15) or 5 ml (P0) 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer using a hand-held 10-ml syringe. Ages were verified by measurement of crown-rump lengths. Sex determination was made through direct inspection of the gonads and PCR analysis for the sry gene on the Y chromosome. Brains were postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight and then placed in 0.1 M phosphate buffer and stored at 4°C until tissue sectioning. All experiments were carried out in accordance with the NIH Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals and the Colorado State University Animal Care and Use Committee.

II.ii. Genotyping

Genotyping of tail DNA was done as described previously (15). Mice were genotyped for the GABABR1 knockout allele and the sry gene using a standard Taq polymerase PCR kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Results from pups heterozygous for the GABABR1 knockout allele were pooled with wild-type mice as controls, since no heterozygote phenotypes have been observed for any characteristic in these mice.

II.iii. Immunohistochemistry

Brain tissue collected from pups at ages E13, E15, and P0 were embedded in 5% agarose and cut into 50μm thick coronal sections using a vibrating microtome (Leica VT1000S). Alternating (P0) or serial (E13 and E15) sections were collected in 0.05 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.5. Excess unreacted aldehyde was neutralized using a 30-minute incubation in 0.1 M glycine and 15 minutes in 0.5% sodium borohydride in PBS. After washing tissue sections in PBS, they were incubated in a PBS blocking solution for 1 hour at 4°C containing 5% normal goat serum, 0.3% Triton X-100 (Tx), and 1% hydrogen peroxide. After the blocking step, the tissue was incubated in primary antisera containing 1% BSA and 0.3%Tx. Anti-CRH antibody was generously provided by Dr. W. Vale and used at dilutions ranging from 1:25,000 to 1:100,000. Tissue sections were incubated over 2 nights at 4°C with primary antiserum. Sections were washed at room temperature in PBS containing 1% normal goat serum and 0.02% Tx. Sections were then incubated at room temperature in secondary antisera using a buffer containing 1% normal goat serum and 0.32% Tx with a biotin conjugated anti-rabbit secondary diluted to 1:2,500 (rabbit IgG-fab fragment; Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA). Sections were further processed using a Vectastain ABC Elite kit (3μl of reagents A and B per ml) (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 1 hour at room temperature. Reaction product was produced in a 5-minute incubation in Tris-buffered saline (pH 7.5) containing 0.025% diaminobenzidine (DAB) with 0.02% nickel and 0.02% H2O2.

To determine if changes seen in the number of immunoreactive neurons (in P0 GABAB KO vs control analysis) was due to a difference in the number of neurons expressing CRH or the amount of CRH produced in those neurons, the primary antiserum was used at two dilutions (1:50,000 and 1:100,000). The 1:50,000 dilution produced maximal signal without elevated background immunoreactivity in the PVN of newborn mice. The 1:100,000 dilution was used to maximize the dynamic range of the immunoreactive product that was generated relative to different antigen concentrations given a fixed 5 minute DAB/nickel reaction time. Tissue sections used for direct comparison to assess GABAB receptor regulation of CRH were processed in parallel in the same immunohistochemical run. Males and females were not processed together therefore comparisons were not made between the sexes. Embryonic characterization of CRH development was achieved using the CRH antiserum at a 1:25,000 dilution (16).

II.iv. Data Analysis

To assess the influence of functional GABAB receptors on immunoreactive CRH, images of the PVN were taken with a 10× objective on an Olympus BH2 microscope, an Insight QE digital camera, and Spot Advanced Software. All images used for direct comparisons were acquired in the same session with the same illumination intensity and capture time. Two independent image analysis methods were used to verify findings. In the first method we directly counted the number of CRH immunoreactive neurons after images were thresholded to 75 on a scale of 0 to 256 using MetaMorph Image analysis software (Metamorph Offline version 7.7.1.0, Molecular Devices, Inc.). In the second method immunoreactive area was quantified in IP Lab Imaging software (Scanalytics Inc., part of BD Biosciences, Rockville, MD) as reported previously (16). All analysis was done with investigators blinded to genotype. Photomicrographs were normalized for optimal contrast using the “levels” tool and image quality was enhanced using the “unsharp mask” tool in Adobe Photoshop (version CS for Macintosh).

To assess the region dependent component of changes in CRH immunoreactive levels, sections containing PVN were arranged rostral to caudal. As we sectioned at 50μm, 6 to 7 sections per pup contained immunoreactive CRH in the PVN. Alternating sections were split between two antibody concentrations, with 3 to 4 sections per concentration containing immunoreactive CRH in the PVN. IP lab was used to quantify immunoreactivity in the most rostral section, middle section and most caudal section for each antibody concentration. In the two cases, where more than 3 sections were present, the section with the least immunoreactivity was dropped from analysis (containing no more than 3 or 4 immunoreactive cells).

To ensure that any changes in immunoreactive area were not due to alterations in cell size, CRH cell body width (perpendicular to neurite extension) was measured using Metamorph Image Analysis Software line tool. Widths of immunoreactive CRH neurons ranged from 7.7 μm to 15.5 μm with no statistically significant differences between genotypes.

III. Results

III.i. Pattern of immunoreactive CRH in development

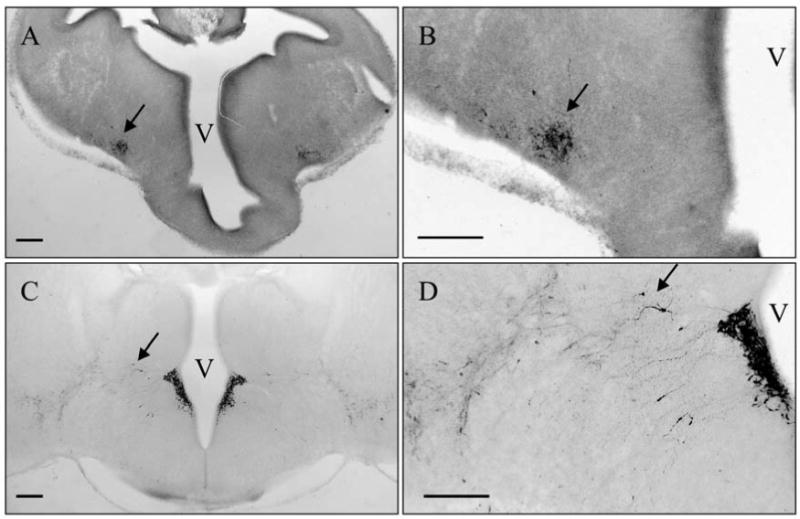

Immunoreactive CRH peptide was first detected in the developing brain in distinct cell bodies lateral to the hypothalamus on E13 (Fig 1A and B) with few cell bodies in the region of the PVN. At E15 the PVN was populated by a robust complement of CRH immunoreactive neurons (Fig. 1C and D) that corresponds with the developmental timing for CRH mRNA in the PVN reported previously (17). Also at E15 (Fig 1C and D) there were a number of neurons between the PVN and the region lateral to the hypothalamus where CRH neurons were visible at E13. At P0 CRH immunoreactive neurons were no longer found between the PVN and the lateral regions. Thus, while CRH immunoreactivity in the lateral regions became more diffuse and less robust, CRH immunoreactivity in the PVN increased. Weak CRH immunoreactivity was seen at the median eminence and the posterior pituitary at E15 (data not shown) that notably increased in strength at P0 (Figure 2). At P0 CRH immunoreactivity clearly delineated the amygdala with a diffuse distribution of immunoreactive neurons extending from the amygdala, in apparent continuity along the stria terminalis, to the Bed Nucleus of the Stria Terminalis (BNST). At P0, weakly immunoreactive CRH neurons were also found diffusely through the preoptic area and hippocampus (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Developmental Pattern of CRH Immunoreactivity. CRH immunoreactive neurons were first visible in a region lateral to the PVN (arrows) at E13 (A, B). Later, CRH immunoreactive neurons populate the PVN while the lateral CRH group becomes more defuse and CRH neurons were found between the two regions at E15 (arrows) (C, D). The images in B and D are higher magnifications of the images in A and B, respectively. Scale bars indicate 200μm. Third Ventricle; V.

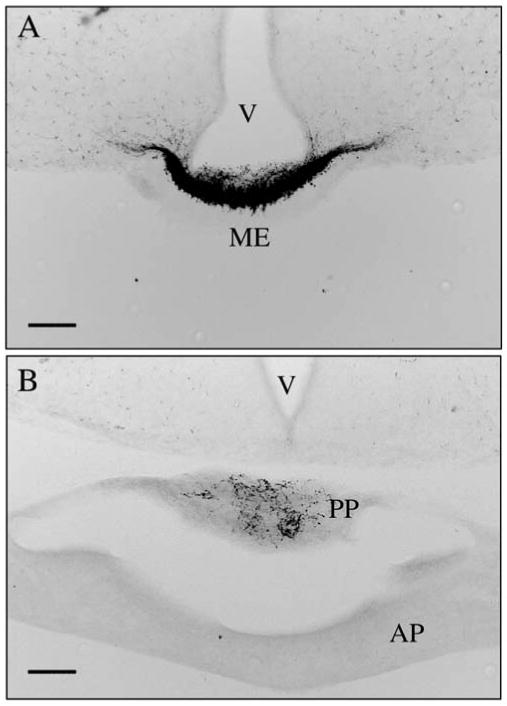

Figure 2.

In newborn mice CRH immunoreactive fibers were seen in the median eminence (ME; panel A) and posterior pituitary (B). In panel B both anterior (AP) and posterior (PP) lobes of the pituitary are visible with immunoreactivity limited to the posterior lobe. Scale bars indicate 100μm. Third Ventricle; V.

III.ii. Impact of GABAB receptors on levels of immunoreactive CRH

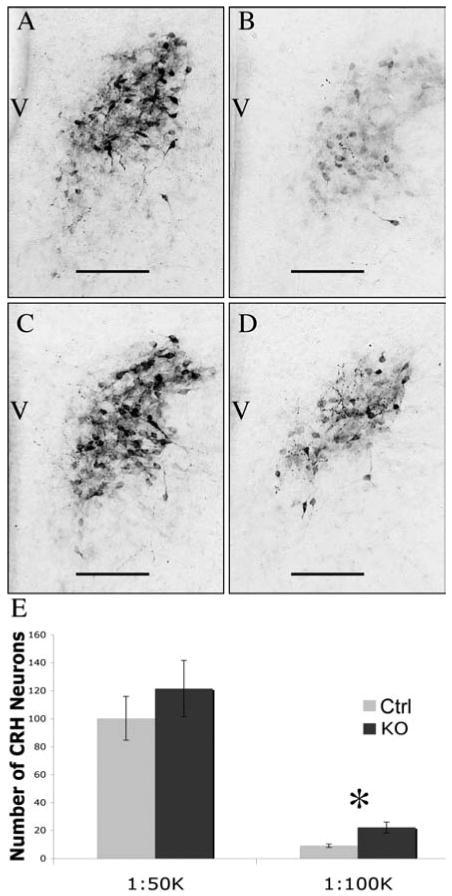

On the day of birth (P0) female mice that lacked functional GABAB receptors had more immunoreactive CRH peptide than controls (Fig. 3). When the anti-CRH antiserum was used at a 1:100K dilution, more than twice as many CRH immunoreactive neurons were labeled above threshold in female KO mice as compared to female control mice (Thresholded cell counts: T test Mean; CTRL 9.3 ± 1.3, KO 22.0 ± 3.9; N=4, df=6, p=0.01 and done by immunoreactive area in pixels: T test Mean; CTRL 829.8 ± 146.7, KO 1844.8 + 434.9; N=4, df=6, p=0.03). There was no statistically significant difference in the number of CRH immunoreactive neurons above threshold when the anti-CRH antibody was used at a 1:50K dilution (Thresholded cell counts: T test Mean; CTRL 100.3 ±15.6, KO 121.5 ± 20.0; N=4, df=6, p=0.22 and done by immunoreactive area in pixels: T test Mean; CTRL 7548.5 ± 1174.8, KO 10482 ± 2637.8; N=4, df=6, p=0.17). This suggests that there was no difference in the number of neurons that produce CRH peptide, but rather a change in the amount of peptide present.

Figure 3.

GABAB Receptor Regulation of Newborn Female CRH Immunoreactivity in the PVN. P0 female mice that lacked functional GABAB receptors (C and D) had more immunoreactive CRH peptide than control littermates (A and B). There was no statistically significant difference seen when the antiserum was used at 1:50,000 dilution (A and C) while knockouts (D) had more than twice as many immunoreactive neurons compared to control (B) when the antiserum was used at a 1:100,000 dilution. Data are neuron counts in images after thresholding in Metamorph and are displayed graphically in panel E. There were 4 animals in each group. Error bars represent standard error of the mean, scale bars indicate 100 μm, and ✽ indicates p<0.05 based on posthoc analysis. Third Ventricle; V.

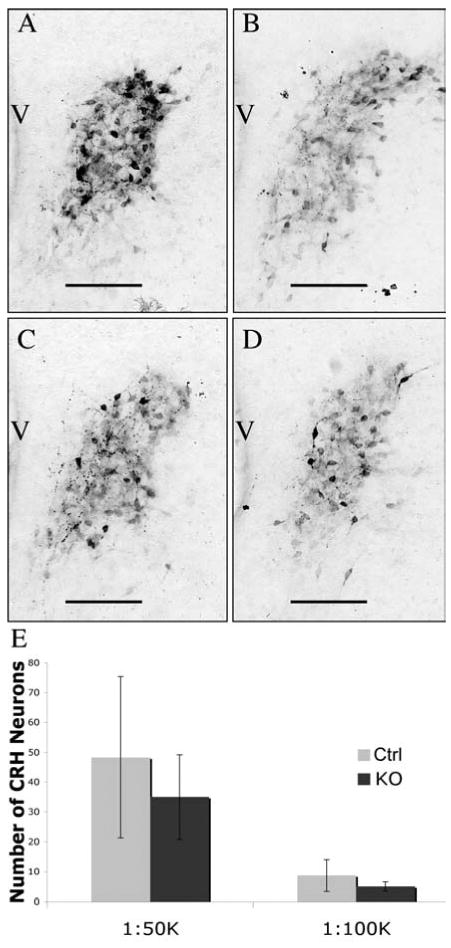

Two separate experiments were done for males (N=3 for each). There was more variability seen in male data compared to female data and neither of the individual experiments yielded statistically reliable differences in CRH immunoreactivity above threshold when quantified by either method (cell number or immunoreactive area; Figure 4). To ensure that statistical significance was not absent due to the small sample size (3) in the individual experiments, the two separate replicates using males were normalized to each other by creating a ratio of the means, thus increasing the total sample sizes to 6. Again there were no statistically reliable differences in CRH immunoreactivity (1:50,000 immunoreactive area in pixels: T test Mean; CTRL 7528 ± 1735.6, KO 9030 ± 1180.2; N=6 df=10 p=0.24 and for the more dilute 1:100,000 immunoreactive area in pixels: T test Mean; CTRL 1716 ± 613.2, KO 2402 ± 884.2; N=6 df=10 p=0.22).

Figure 4.

Lack of GABAB Receptor Regulation of Newborn Male CRH Immunoreactivity in the PVN. P0 male mice that lacked functional GABAB receptors (C and D) had the same amount of immunoreactive CRH peptide as wild type littermates (A and B). There was no statistically significant difference between genotypes when the antiserum was used at either the 1:50,000 dilution (A and C) or the 1:100,000 dilution (B and D). Data are from neuron counts in images after thresholding in Metamorph and are displayed graphically in panel E. There were 3 animals in each group. Error bars represent standard error of the mean and scale bars indicate 100 μm. Third ventricle; V.

III.iii. Region specific impact of GABAB receptors on immunoreactive CRH in females

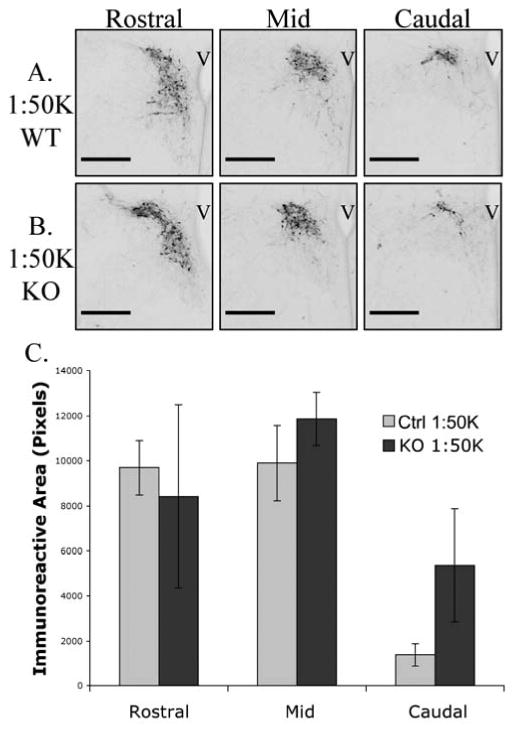

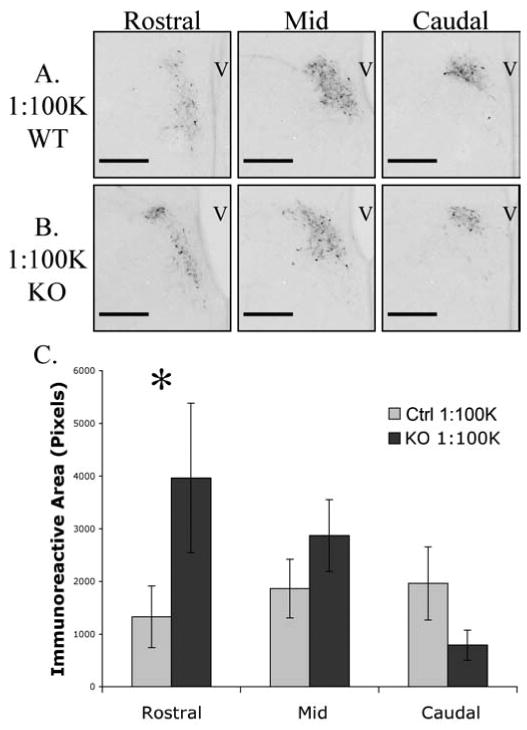

Immunoreactive CRH neurons were not uniformly distributed throughout the PVN as fewer cells were seen in caudal sections (Figure 5). At the 1:50K concentration of antiserum, there were no genotype differences in the rostral, middle, or caudal PVN sections (genotype × location as a repeated measure, F(2,12) = 0.656, p > 0.05). When images were analyzed from adjacent sections, processed at the more dilute 1:100K, there were significantly greater levels of immunoreactive CRH above threshold in rostral sections in the GABAB receptor KOs compared to control littermates (Figure 6). Rostral sections from female KO mice had three-fold more CRH immunoreactivity above threshold than rostral sections from control mice. Repeated measures analysis revealed a significant genotype × location interaction (F(2,16) = 3.87, p<0.05). The effect was due almost entirely to a significant increase in CRH immunoreactivity above threshold in the rostral sections of KO mice compared to control based on a posthoc analysis of the 95% confidence interval for the rostral sections. There was little difference in immunoreactivity in the middle or caudal PVN sections between genotypes at the more dilute antiserum concentration.

Figure 5.

Rostral to caudal distribution of CRH immunoreactivity in newborn female mice when primary antiserum was used at a 1:50,000 dilution. There were similar levels of CRH immunoreactivity in sections from rostral, middle and caudal PVN from control (A) and knockout (B) neonates. Data is displayed graphically in panel C; there was no statistically significant interaction between genotype and location analyzed as a repeated measure. Error bars represent standard error of the mean and scale bars indicate 200μm. Third ventricle; V.

Figure 6.

Rostral to caudal distribution of CRH immunoreactivity in newborn female mice when primary antiserum was used at the 1:100,000 dilution. Rostral sections from female KO mice (B) had three-fold more CRH immunoreactivity than rostral sections from control mice (A). Data is displayed graphically in panel C. Repeated measures analysis revealed a significant genotype × location interaction that was due almost entirely to a significant increase in CRH immunoreactivity in the rostral sections of KO mice compared to control based on a posthoc analysis of the 95% confidence interval for the rostral sections (p < 0.05). Error bars represent standard error of the mean and scale bars indicate 200μm. Third ventricle; V.

IV. Discussion

CRH is a critical peptide for the function of the HPA axis, particularly when originating from neurons in the PVN. In the current study, immunoreactive CRH was examined from the perspective of developmental time course and from the perspective of GABAB receptor regulation. Immunoreactive CRH was first visible during mouse brain development in a region lateral to the PVN, later becoming apparent in the PVN, while some CRH immunoreactive neurons were found in the region between these two locations. Whether the changing location of CRH immunoreactive cells indicates neuronal migration remains to be determined. In the absence of functional GABAB receptors, CRH immunoreactive neurons were found in the same places, but distinctive changes in CRH immunoreactivity were revealed between rostral and caudal regions of the PVN. Loss of functional GABAB receptors resulted in more CRH immunoreactivity in the rostral PVN. Interestingly, this relationship was only found in females. The results of the current study emphasize that the local relationship between a global neurotransmitter, like GABA, and a small nuclear group, like the PVN, can vary significantly as a function of sex and location.

The developmental pattern of CRH immunoreactivity in the PVN (figure 1) is suggestive of a migratory route for CRH neurons from an extra hypothalamic region into the PVN. This would be a novel model of PVN development. The changing positions of phenotypically identified cells at different ages during development is frequently associated with migration (e.g., 18, 19, 20). There is precedent for suggesting that cells migrate into the PVN from lateral regions (21, 22). In the development of the vasopressin (AVP) system, where AVP is present in both the SON and PVN, some have hypothesized that AVP neurons migrate from the proliferative zone adjacent to the PVN to the SON, with a subpopulation reversing direction and returning to the PVN to make up the AVP positive cells in the adult (21). Video microscopy has revealed unexpected directions for neuron migration in different brain regions, including gonadotropin-releasing hormone containing neurons (23) and neurons that migrate ventrally in the cerebral cortex toward the ventricular zone (24). Fluorescent cells have been identified moving toward the PVN from lateral regions using video microscopy in organotypic slices dissected from E13 mice (Stratton, Searcy, and Tobet, unpublished observations).

The presence of CRH fibers in the median eminence prenatally, and in the posterior pituitary at birth (figure 2), indicates a potential active role for CRH regulation of early developmental events. CRH receptors, while present in large densities in the central nervous system, are also present in several peripheral organs including the spleen (25), heart (26), skin (27) and adrenal gland (28). Although first reported almost 30 years ago (29), little is known about the physiological significance of CRH immunoreactive fibers in the posterior pituitary. Immunoreactive CRH has been reported in magnocellular oxytocin neurons thought to project to the posterior pituitary (30). The current data, however, provides direct evidence of immunoreactive CRH in fibers in the mouse posterior pituitary during early development.

The data in the current study indicates that cells containing immunoreactive CRH in the rostral extension of the PVN are more impacted by the loss of functional GABAB receptors than central and caudal neurons. In the rostral sections, loss of GABAB receptors resulted in significantly elevated levels of immunoreactive CRH. This suggests alternate roles for GABAB signaling on CRH expression in different regions of the PVN. Although mostly described in rat, others have shown functionally specific projections of parvocellular neurons (either to median eminence or brain stem/caudal brain structures (31, 32)) and identified protein co-expression in CRH neurons (steroid receptors; 33) based on spatial distributions within the PVN. A recent investigation of the location of neurons in the PVN that contain thyrotropin-releasing hormone in mice (34) revealed that those TRH neurons projecting to the median eminence are differentially segregated in the PVN. Together, this indicates a high degree of compartment specific regulation of developmental processes within the PVN. Due to the fact that rostral PVN was more impacted by the loss of functional GABAB receptors, a closer examination of GABAB R1 immunoreactivity was undertaken. The GABAB receptor is present during embryonic development and enriched in the PVN, but there was no obvious rostral bias to GABAB R1 immunoreactivity in the PVN noted (data not shown).

The current data suggest a GABAB receptor dependent regulation of CRH peptide that may be sex specific. The observation that CRH immunoreactivity was altered by the lack of functional GABAB receptors only in female mice is an example of a sex-specific mechanism of protein regulation. While there are multiple examples of sex differences in protein expression in particular brain locations, there are fewer examples of sex-specific mechanisms of regulation. Interestingly, there are changes in the locations of estrogen receptor α cells in the PVN of the same line of GABAB receptor KO mice, also in the same sex-dependent manner (females only; 16). This could indicate that female mice are more dependent on GABAB receptor signaling for the development of the PVN compared to males. By contrast, there was no indication of sex dependent changes in estrogen receptor α containing cells in GABAB R1 subunit KO mice in the region of the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus (15).

It is unclear if the reported increase in CRH immunoreactivity is a primary effect of loss of functional GABAB receptors or if it is due to some other mechanism that is perturbed in the GABAB R1 knockout. Previously reported phenotypes of the PVN in these mice include altered distribution of ERα and nNOS along with decreased BDNF immunoreactivity. Both nitric oxide (35, 36) and BDNF (37, 38) have been shown to influence HPA axis activity and CRH secretion. The mislocalization of ERα in the GABAB R1 knockout might be of particular importance as estrogens act through ERα to create more robust HPA axis activity in response to stressors, (reviewed in 39). There is also evidence for direct estradiol regulation of CRH expression (40) and changes in stress response throughout the female reproductive cycle (41).

Several other factors have also been shown to influence CRH expression at either mRNA or peptide levels. The HPA axis and CRH neurons in the PVN are often under glucocorticoid mediated negative feedback (reviewed; 42). As noted above sex steroid hormones have also been shown to regulate CRH expression. For the current study, however, females were taken at P0, when the ovary is thought to be relatively quiescent. Interestingly, at this point in development there is likely variability in testosterone levels in males as testes in different males may produce different amounts of hormone, possibly explaining the increased variability seen in the current male CRH data. In addition to circulating factors, locally secreted factors (or neurotransmitters) like GABA (43) can influence HPA axis activity and CRH expression. GABAergic neurons have been shown to innervate the PVN (44, 2) and specifically CRH neurons (45). When GABA degradation was blocked with γ-vinyl-GABA, CRH mRNA and peptide was increased in the PVN/anterior hypothalamus, but not other brain regions (46). GABA acting through GABAB receptors in the PVN dampens HPA output in response to stress. When phaclofen was used to antagonize GABAB receptors in the PVN, stress induced corticosterone secretion was increased (47). There is, however, no previous evidence to suggest that either of these factors impact CRH expression in neonatal rodents as was seen in the current study using mice. Unfortunately, on the C57BL/6 background, GABAB R1 deficient mice die from seizures on or around P21 (13), which makes adult HPA axis and behavior testing impossible. However, on the BALB/c background these mice survive into adulthood and show increased anxiety-like behaviors (reviewed in 12).

There are multiple levels of regulation that might affect the amount of CRH peptide present in cells of the PVN. Protein levels can be regulated by transcriptional activity, transcript stability, translational activity, protein stability and peptide secretion. In preliminary experiments to examine CRH from an mRNA perspective, we used quantitative real-time PCR to examine CRH mRNA in GABAB R1 knockouts at P0. The preliminary data indicated a potential 50% decrease in the copy number of CRH mRNA in female knockouts compared to wild type littermates (t-test, n=3(control),4(KO); p=0.03). Thus the increase in apparent immunoreactive content might be independent of gene transcription regulation. Given the complexities of peptide regulation, it is difficult to determine the precise physiological consequences of these differences. Nonetheless, the preliminary mRNA data and the immunohistochemical results suggest that the loss of functional GABAB receptor signaling impacts the physiological handling of CRH.

Increased amounts of CRH mRNA, CRH peptide and CRH containing cells have been associated with human depression (9, 10). When looking at the downstream effects of long term HPA axis activity it is interesting to note that disorders resulting from dysregulation of the HPA axis like major depressive disorder and anxiety related disorders, are more prevalent in females than males. Our data that females but not males lacking functional GABAB receptors have more CRH peptide in the PVN might help to explain some of the predisposition of disorders resulting from HPA axis dysregulation in females. That is to say, if a mutation or insult affecting the GABAB signaling system resulted in altered HPA axis activity and behavior it might preferentially impact females.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institutes of Health; Grant number: P01-MH082679 (S.A.T.); National Science Foundation; Grant number: DGE-0841259 (S.A.T., M.S.S.). We thank Chad Eitel for assistance with the computer assisted analysis and Drs. Robert Handa and Jill Goldstein for comments on the project and the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Swanson LW, Sawchenko PE. Hypothalamic integration: organization of the paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1983;6:269–324. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.06.030183.001413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herman JP, Ostrander MM, Mueller NK, Figueiredo H. Limbic system mechanisms of stress regulation: hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29(8):1201–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bao AM, Meynen G, Swaab DF. The stress system in depression and neurodegeneration: focus on the human hypothalamus. Brain Res Rev. 2008;57(2):531–53. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewinsohn PM, Gotlib IH, Lewinsohn M, Seeley JR, Allen NB. Gender differences in anxiety disorders and anxiety symptoms in adolescents. J Abnorm Psychol. 1998;107(1):109–17. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pigott TA. Gender differences in the epidemiology and treatment of anxiety disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(Suppl 18):4–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nolen-Hoeksema S. Sex Differences in Unipolar Depression: Evidence and Theory. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;101(2):259–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Angst J, Gamma A, Gastpar M, Lépine JP, Mendlewicz J, Tylee A. Depression Research in European Society Study. Gender differences in depression. Epidemiological findings from the European DEPRES I and II studies. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2002;252(5):201–9. doi: 10.1007/s00406-002-0381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferguson A, Latchford, Samson W. The Paraventricular Nucleus of the hypothalamus – a Potential Target for Integrative Treatment of Autonomic Dysfunction. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2008;12(6):717–21. doi: 10.1517/14728222.12.6.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raadsheer FC, Hoogendijk WJ, Stam FC, Tilders FJ, Swaab DF. Increased numbers of corticotropin-releasing hormone expressing neurons in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus of depressed patients. Neuroendocrinology. 1994;60(4):436–44. doi: 10.1159/000126778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raadsheer FC, van Heerikhuize JJ, Lucassen PJ, Hoogendijk WJ, Tilders FJ, Swaab DF. Corticotropin-releasing hormone mRNA levels in the paraventricular nucleus of patients with Alzheimer's disease and depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(9):1372–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.9.1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalueff AV, Nutt DJ. Role of GABA in anxiety and depression. Depress Anxiety. 2007;24(7):495–517. doi: 10.1002/da.20262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cryan JF, Kaupmann K. Don't worry ‘B’ happy!: a role for GABA(B) receptors in anxiety and depression. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26(1):36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prosser HM, Gill CH, Hirst WD, Grau E, Robbins M, Calver A, Soffin EM, Farmer CE, Lanneau C, Gray J, Schenck E, Warmerdam BS, Clapham C, Reavill C, Rogers DC, Stean T, Upton N, Humphreys K, Randall A, Geppert M, Davies CH, Pangalos MN. Epileptogenesis and enhanced prepulse inhibition in GABA(B1)-deficient mice. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2001;17(6):1059–70. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2001.0995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frankowska M, Filip M, Przegaliński E. Effects of GABAB receptor ligands in animal tests of depression and anxiety. Pharmacol Rep. 2007;59(6):645–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McClellan KM, Calver AR, Tobet SA. GABAB receptors role in cell migration and positioning within the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus. Neuroscience. 2008;151(4):1119–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.11.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McClellan KM, Stratton MS, Tobet SA. Roles for gamma-aminobutyric acid in the development of the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. J Comp Neurol. 2010;15;518(14):2710–28. doi: 10.1002/cne.22360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keegan CE, Karolyi IJ, Knapp LT, Bourbonais FJ, Camper SA, Seasholtz AF. Expression of corticotropin-releasing hormone transgenes in neurons of adult and developing mice. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1994;5(6):505–14. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1994.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wray S, Grant P, Gainer H. Evidence that cells expressing luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone mRNA in the mouse are derived from progenitor cells in the olfactory placode. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86(20):8132–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.20.8132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwanzel-Fukuda M, Pfaff DW. Origin of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone neurons. Nature. 1989;338(6211):161–4. doi: 10.1038/338161a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tobet SA, Henderson RG, Whiting PJ, Sieghart W. Special relationship of gamma-aminobutyric acid to the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus during embryonic development. J Comp Neurol. 1999;405(1):88–98. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19990301)405:1<88::aid-cne7>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ugrumov MV. Magnocellular vasopressin system in ontogenesis: development and regulation. Microsc Res Tech. 2002;56(2):164–71. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whitnall MH, Key S, Ben-Barak Y, Ozato K, Gainer H. Neurophysin in the hypothalamo-neurohypophysial system. II. Immunocytochemical studies of the ontogeny of oxytocinergic and vasopressinergic neurons. J Neurosci. 1985;5(1):98–109. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-01-00098.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bless EP, Walker HJ, Yu KW, Knoll JG, Moenter SM, Schwarting GA, Tobet SA. Live view of gonadotropin-releasing hormone containing neuron migration. Endocrinology. 2005;146(1):463–8. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nadarajah B, Alifragis P, Wong RO, Parnavelas JG. Ventricle-directed migration in the developing cerebral cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5(3):218–24. doi: 10.1038/nn813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Webster EL, Tracey DE, Jutila MA, Wolfe SA, Jr, De Souza EB. Corticotropin-releasing factor receptors in mouse spleen: identification of receptor-bearing cells as resident macrophages. Endocrinology. 1990;127(1):440–52. doi: 10.1210/endo-127-1-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heldwein KA, Redick DL, Rittenberg MB, Claycomb WC, Stenzel-Poore MP. Corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor expression and functional coupling in neonatal cardiac myocytes and AT-1 cells. Endocrinology. 1996;137(9):3631–9. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.9.8756527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roloff B, Fechner K, Slominski A, Furkert J, Botchkarev VA, Bulfone-Paus S, Zipper J, Krause E, Paus R. Hair cycle-dependent expression of corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) and CRF receptors in murine skin. FASEB J. 1998;12(3):287–97. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.3.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Müller MB, Preil J, Renner U, Zimmermann S, Kresse AE, Stalla GK, Keck ME, Holsboer F, Wurst W. Expression of CRHR1 and CRHR2 in mouse pituitary and adrenal gland: implications for HPA system regulation. Endocrinology. 2001;142(9):4150–3. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.9.8491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bloom FE, Battenberg EL, Rivier J, Vale W. Corticotropin releasing factor (CRF): immunoreactive neurones and fibers in rat hypothalamus. Regul Pept. 1982;4(1):43–8. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(82)90107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sawchenko PE, Swanson LW, Vale WW. Corticotropin-releasing factor: co-expression within distinct subsets of oxytocin-, vasopressin-, and neurotensin-immunoreactive neurons in the hypothalamus of the male rat. J Neurosci. 1984;4(4):1118–29. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-04-01118.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geerling JC, Shin JW, Chimenti PC, Loewy AD. Paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus: axonal projections to the brainstem. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518(9):1460–99. doi: 10.1002/cne.22283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simmons DM, Swanson LW. Comparison of the spatial distribution of seven types of neuroendocrine neurons in the rat paraventricular nucleus: toward a global 3D model. J Comp Neurol. 2009;516(5):423–41. doi: 10.1002/cne.22126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bingham B, Williamson M, Viau V. Androgen and estrogen receptor-beta distribution within spinal-projecting and neurosecretory neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the male rat. J Comp Neurol. 2006 Dec 20;499(6):911–23. doi: 10.1002/cne.21151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kádár A, Sánchez E, Wittmann G, Singru PS, Füzesi T, Marsili A, Larsen PR, Liposits Z, Lechan RM, Fekete C. Distribution of hypophysiotropic thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH)-synthesizing neurons in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus of the mouse. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518(19):3948–61. doi: 10.1002/cne.22432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gadek-Michalska A, Bugajski J. Nitric oxide in the adrenergic-and CRH-induced activation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;59(2):365–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hsieh CH, Li HY, Chen JC. Nitric oxide and interleukin-1beta mediate noradrenergic induced corticotrophin-releasing hormone release in organotypic cultures of rat paraventricular nucleus. Neuroscience. 2010;165(4):1191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Givalois, Naert G, Rage F, Ixart G, Arancibia S, Tapia-Arancibia L. A single brain-derived neurotrophic factor injection modifies hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical axis activity in adult male rats. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2004;27:280–295. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naert, Ixart G, Tapia-Arancibia L, Givalois L. Continuous i.c.v. infusion of brain-derived neurotrophic factor modifies hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity, locomotor activity and body temperature rhythms in adult male rats. Neuroscience. 2006;139:779–789. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Handa RJ, Weiser MJ, Zuloaga DG. A role for the androgen metabolite, 5alpha-androstane-3beta,17beta-diol, in modulating oestrogen receptor beta-mediated regulation of hormonal stress reactivity. J Neuroendocrinol. 2009;21(4):351–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2009.01840.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lalmansingh AS, Uht RM. Estradiol regulates corticotropin-releasing hormone gene (crh) expression in a rapid and phasic manner that parallels estrogen receptor-alpha and -beta recruitment to a 3′,5′-cyclic adenosine 5′-monophosphate regulatory region of the proximal crh promoter. Endocrinology. 2008;149(1):346–57. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Altemus M, Roca C, Galliven E, Romanos C, Deuster P. Increased vasopressin and adrenocorticotropin responses to stress in the midluteal phase of the menstrual cycle. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(6):2525–30. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.6.7596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watts AG. Glucocorticoid regulation of peptide genes in neuroendocrine CRH neurons: a complexity beyond negative feedback. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2005;26(3-4):109–30. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cullinan WE, Ziegler DR, Herman JP. Functional role of local GABAergic influences on the HPA axis. Brain Struct Funct. 2008;213(1-2):63–72. doi: 10.1007/s00429-008-0192-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Herman JP, Tasker JG, Ziegler DR, Cullinan WE. Local circuit regulation of paraventricular nucleus stress integration: glutamate-GABA connections. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;71(3):457–68. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00681-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miklós IH, Kovács KJ. GABAergic innervation of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH)-secreting parvocellular neurons and its plasticity as demonstrated by quantitative immunoelectron microscopy. Neuroscience. 2002;113(3):581–92. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00147-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tran V, Hatalski CG, Yan XX, Baram TZ. Effects of blocking GABA degradation on corticotropin-releasing hormone gene expression in selected brain regions. Epilepsia. 1999;40(9):1190–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb00847.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marques de Souza L, Franci CR. GABAergic mediation of stress-induced secretion of corticosterone and oxytocin, but not prolactin, by the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. Life Sci. 2008;83(19-20):686–92. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]