Abstract

The type-A receptors for the neurotransmitter GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid) are ligand-gated chloride channels that mediate postsynaptic inhibition. The functional diversity of these receptors comes from the use of a large repertoire of subunits encoded by separate genes, as well as from differences in subunit composition of individual receptors. In mammals, a majority of GABAA receptor subunit genes are located in gene clusters that may be important for their regulated expression and function. We have established a high-resolution physical map of the cluster of genes encoding GABAA receptor subunits α2 (Gabra2), β1 (Gabrb1), and γ1 (Gabrg1) on mouse chromosome 5. Rat cDNA probes and specific sequence probes for all three GABAA receptor subunit genes have been used to initiate the construction of a sequence-ready contig of bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs) encompassing this cluster. In the process of contig construction clones from 129/Sv and C57BL/6J BAC libraries were isolated. The assembled 1.3-Mb contig, consisting of 45 BACs, gives five- to sixfold coverage over the gene cluster and provides an average resolution of one marker every 32 kb. A number of BAC insert ends were sequenced, generating 30 new sequence tag sites (STS) in addition to 6 Gabr gene-based and 3 expressed sequence tag (EST)-based markers. STSs from, and surrounding, the Gabrg1–Gabra2–Gabrb1 gene cluster were mapped in the T31 mouse radiation hybrid panel. The integration of the BAC contig with a map of loci ordered by radiation hybrid mapping suggested the most likely genomic orientation of this cluster on mouse chromosome 5: cen–D5Mit151–Gabrg1–Gabra2–Gabrb1–D5Mit58–tel. This established contig will serve as a template for genomic sequencing and for functional analysis of the GABAA gene cluster on mouse chromosome 5 and the corresponding region on human chromosome 4.

The sequence data described in this paper have been submitted to the GenBank/GSS data libraries under accession nos. AF156490 and AQ589406–AQ589436.

γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) is a potent inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system (CNS) that interacts with two different classes of GABA receptors: the ionotrophic GABAA receptor chloride channels (for review, see Rabow et al. 1995; Seeburg et al. 1990) and the recently cloned metabotropic G-protein-coupled GABAB receptors (Kaupmann et al. 1997, 1998).

GABAA receptors are multimeric membrane-spanning ligand-gated ion channels that admit chloride on binding of the neurotransmitter GABA (Bormann et al. 1987). Because GABA is the major inhibitory neurotransmitter of the CNS, modulation of receptor activity has profound implications for both brain function and therapy of various neuropsychiatric disorders. Drugs that alter the GABAA receptor channel activity, such as benzodiazepines, barbiturates, and steroids, have had important roles in the understanding and treatment of anxiety, sleep disorders, convulsive disorders, and epilepsy (for review, see Burt and Kamatchi 1991; Brooks-Kayal et al. 1998; Shiah and Yatham 1998).

Functional studies of the individual GABAA receptor genes have been hindered by a high structural diversity among the GABAA receptor subunits that assemble combinatorially to build different subtypes of GABAA receptors in various regions of the brain and the spinal cord. To date nineteen distinct subunit types (α1–α6, β1–β4, γ1–γ4, δ1, ε, ρ1–ρ3) have been identified and this isoform complexity is further complicated by the occurrence of alternative splicing and post-translational modifications (Wisden and Seeburg 1992). In the mammalian genome, many GABAA receptor subunit genes are organized as gene clusters on different chromosomes, with each of these clusters containing at least one gene of the α, β, and γ or ε class. In humans, five GABAA receptor subunit gene clusters have been described. The GABRB2–GABRA1/GABRA6–GABRG2 cluster on human chromosome (HSA) 5q31.2–q35 (Kostrzewa et al. 1998) is homologous to the cluster on mouse chromosome (MMU) 11 (Garrett et al. 1997). Similarly, the GABRB3–GABRA5–GABRG3 gene cluster, located close to the Prader-Willi/Angelman region on HSA 15q11–q13 (Glatt et al. 1997; Christian et al. 1998), corresponds to the Gabrb3–Gabra5–Gabrg3 cluster located distal to the pink-eyed dilution (p) gene region on MMU 7 (Nakatsu et al. 1993; Culiat et al. 1994). An additional cluster, containing the GABRA3, GABRB4, and GABRE2 subunit genes, has been mapped to human chromosome Xq28 (Levin et al. 1996; Wilke et al. 1997) and mouse chromosome X (Boyd et al. 1998). Two GABAA subunit genes, ρ1 and ρ2, expressed at a high level in the retina, have been shown to map to HSA 6q11–q14 and the corresponding region in the proximal portion of MMU 4 (Cutting et al. 1992).

In humans, the GABRA2, GABRG1, and GABRB1 genes have been mapped to HSA 4p12–p13 (Buckle et al. 1989; Kirkness et al. 1991; Wilcox et al. 1992). Furthermore, somatic cell hybrid analysis has indicated that the GABRA4 gene maps to the same cluster (McLean et al. 1995). The murine orthologs, Gabra2 and Gabrb1 subunit genes, have been localized to the central portion of MMU 5, whereas the Gabra4 subunit gene has been assigned to proximal MMU 7 (Danciger et al. 1993). We have previously placed the murine Gabrb1 locus on a long-range restriction map, 3 Mb proximal to the dominant spotting locus (W) encoded by the proto-oncogene c-Kit (Nagle et al. 1995). To gain insight into the genomic organization of the GABAA receptor gene cluster on mouse chromosome 5, we have constructed a sequence-ready bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) contig of 1.3 Mb. This contig has been anchored to other chromosome 5 loci using radiation hybrid (RH) mapping, and the transcriptional orientation of two GABAA receptor subunit genes, Gabra2 and Gabrb1, has been determined. This high-resolution physical map will provide the basis for functional characterization and sequencing of genes located in this cluster.

RESULTS

The contig spanning the GABAA receptor genes in the central portion of mouse chromosome 5 was generated in the following steps: (1) initial hybridization screen; (2) STS content mapping; (3) chromosome walk using selected STSs generated from BAC ends; and (4) fine mapping by fingerprinting and Southern blot analysis. To initiate the construction of a BAC contig, we used Gabra2 and Gabrg1 rat cDNA probes and a mouse Gabrb1 cDNA clone to screen two 129/Sv BAC libraries. We isolated 27 BAC clones, and 23 were confirmed to correspond to GABAA receptor genes by dot-blot colony assays and by Southern blot analysis. The BAC-insert sizes were determined by pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) following a NotI digestion of BAC DNA.

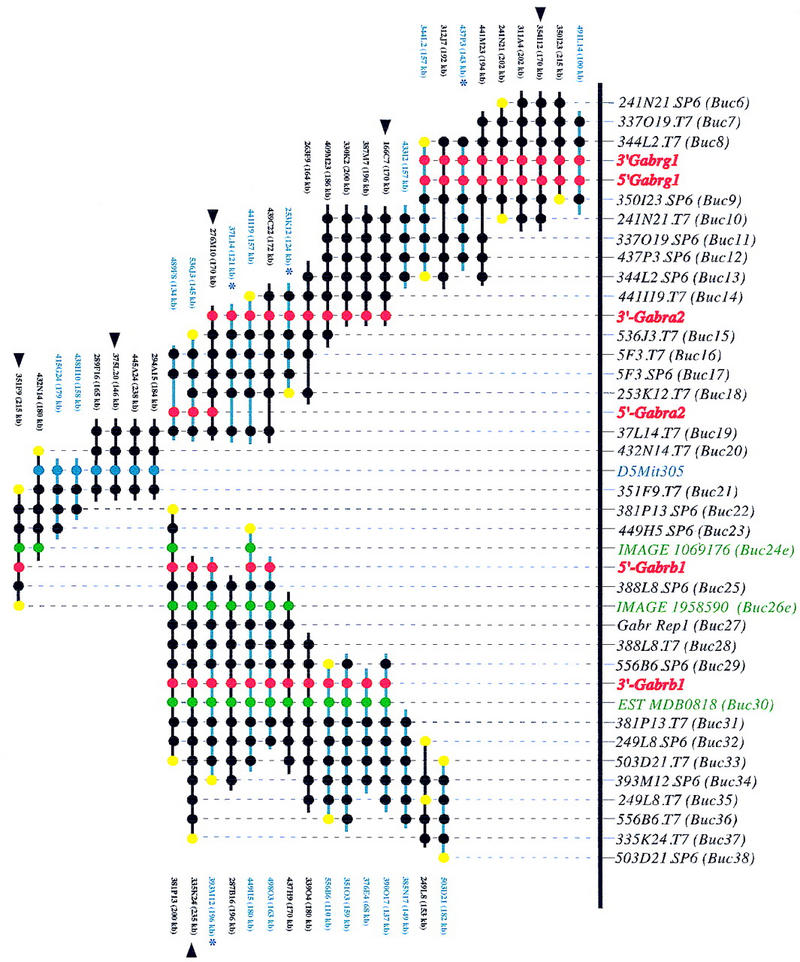

To facilitate further analysis, we selected gene-specific primers for the three GABAA genes (Table 1). Whereas nucleotide sequence of full-length cDNAs was available for the mouse Gabra2 and Gabrb1 subunit genes (Table 1; Wang et al. 1992; Kamatchi et al. 1995), we obtained partial sequence for the mouse Gabrg1 gene by screening an olfactory bulb cDNA library with a rat Gabrg1 probe (Table 1). For each gene, 5′ and 3′ PCR assays were developed and used for BAC contig construction. Among 23 positive BAC clones, 13 BACs were selected for nucleotide sequence analysis of the insert ends (Fig. 1). The nonrepetitive insert end sequences provided 19 new STSs (Table 1). STS mapping using all available markers revealed that we had isolated three independent groups of BACs corresponding to the Gabra2, Gabrb1, and Gabrg1 subunit gene regions with no overlaps between the three groups of clones.

Table 1.

Primers and PCR Conditions for STSs and Genes in the Contig

|

Figure 1.

A BAC-based STS/EST-content map of the Gabr gene cluster on mouse chromosome 5 (oriented with centromeric end at left and telomeric end at right). The relative positions of mapped STSs and ESTs are indicated at top, including the corresponding loci names (D5Buc). The isolated BAC clones are shown as horizontal lines with circles along the lines indicating positive STS hits. The STSs were developed from BAC insert ends (black), known genes (red), ESTs (green), and an SSLP marker D5Mit305 (blue). When an STS corresponds to a clone insert end, a yellow circle is present at the end of the clone from which it was derived. BAC clones were isolated from the C57BL/6J library (black lines), from the 129/Sv library (blue lines), or from the Research Genetics CITB library (*). The size of each BAC as determined by PFGE analysis is indicated. C57BL/6J BAC clones selected to represent the minimal tiling path are indicated by black arrowheads. The map is displayed with equal spacing between STS/EST markers and the depicted clones together span a distance of ∼1300 kb. The orientation of the 5′- and 3′-Gabrg1 markers with respect to surrounding STSs on the contig could not be determined.

To comply with the mouse genome initiative that has designated the C57BL/6J genome as a reference strain for genomic sequencing, further BAC isolation in the GABAA cluster on mouse chromosome 5 was performed by screening a C57BL/6J BAC library. To efficiently convert a 129/Sv clone collection into a C57BL/6J BAC contig, we selected 10 STSs for library screening. Sixteen new C57BL/6J BACs were sized and tested for STS and probe content and precisely positioned to the regions already covered by the 129/Sv BACs. In addition, STSs corresponding to the BAC ends were used to isolate clones that joined the Gabra2 and Gabrg1 groups of BACs, showing that these two genes map within an interval of 370 kb. Furthermore, BAC clones isolated with the D5Mit305 marker filled the gap between the Gabra2 and Gabrb1 BACs. The D5Mit305 marker was the only simple sequence length polymorphism (SSLP) marker among 15 markers assigned to the 41 cM interval on the composite genetic map (Kozak and Stephenson 1998) that mapped to the 1.3 Mb region covered by the BAC contig.

The established BAC contig contains 45 BAC clones, covers a physical distance of about 1.3 Mb, and provides ordering information for 40 new markers. Among these are 29 STSs designed from BAC-insert ends, 5′- and 3′-specific sequence markers developed from GABAA receptor subunit cDNAs, and three new ESTs that were found by sequence homology of BAC ends to mouse EST cDNA clones (Table 1). Overall, this results in an average spacing of 1 marker per 32 kb within the contig and a five- to sixfold coverage with independent BAC clones. Because of the uneven distribution of STSs within the contig, the number of “hits” per BAC clone varies from 3 to 15. Fourteen C57BL/6J-derived BAC clones were selected for fingerprinting of EcoRI-digested DNA (data not shown). The pattern of EcoRI restriction fragments further confirmed the order of clones established by STS content mapping. This analysis identified six BAC clones that represent a minimal tiling path (Fig. 1). The STS content mapping using 5′ and 3′ gene-specific primer pairs and Southern blot analysis determined the transcriptional orientation of the Gabra2 and Gabrb1 genes with respect to contig ends and thus, with respect to each other. The two genes are transcribed in opposite directions (Fig. 1).

Finally, a genomic PCR assay specific for the Gabra4 subunit gene was developed from a partial mouse cDNA sequence (Table 1). Primers were chosen from the portion of the gene encoding the amino-terminal extracellular domain (amino acids 72–166) yielding a 280-bp amplicon in brain cDNA and a genomic PCR product of 1.2 kb. A PCR assay using these primers was performed to test for the presence of the Gabra4 gene on the contig (data not shown). We found no evidence that the Gabra4 gene is located within this GABAA cluster. We have not discounted the possibility that Gabra4 could be located close to, but not within, the 1.3-Mb region covered by the contig.

Nucleotide sequence analysis was performed on 40 BAC ends. The overall percentage of repetitive sequence detected using RepeatMasker in these BAC end-sequences was 17.5%. Three BAC ends contained sequences with high homology to ESTs (Table 1), but no homology to any known gene in the GenBank database. Expression analysis using RT–PCR confirmed that these are indeed transcribed sequences, expressed in several tissues, such as liver, spleen, testis, kidney, lungs and brain (data not shown).

To integrate the Gabrg1–Gabra2–Gabrb1 BAC contig with the existing map of the mouse chromosome 5, we mapped several STSs and chromosome 5 SSLP markers using the mouse whole-genome RH panel. The commonly used T31 panel consists of 100 hybrid cell lines generated with a 3000-rad dose and has been shown to have a retention frequency of 27.6% (McCarthy et al. 1997). In contrast to genetic mapping, which requires markers with SSLP polymorphism between inbred strains used to generate the cross, PCR-based RH mapping requires markers that are present in mouse and absent in hamster DNA, or alternatively, that the amplicons detected in these DNAs are of different size. This makes RH mapping useful as an aid to anchor clone contigs on the chromosome relative to markers previously mapped or ordered along the chromosome. It also enables quick verification of chromosomal position of BAC clones containing members of large gene families.

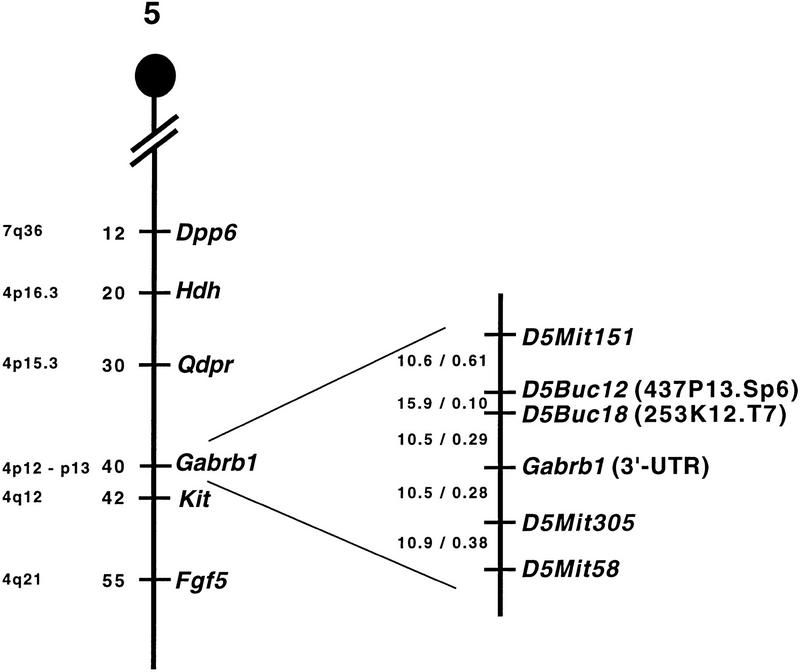

To determine the orientation of our BAC contig, we mapped the following STSs: 253K12.T7(D5Buc18), 473P3.SP6(D5Buc12), and an EST developed from the 3′-UTR of the Gabrb1 gene in the T31 RH panel. We also included the SSLP marker D5Mit305 placed on the contig between Gabra2 and Gabrb1 (Fig. 1). PCR analysis of each marker was performed twice and consensus vector scores (Fig. 2) were entered in a data file containing scores for >50 loci along mouse chromosome 5 (L. Tarantino, C. Otmani, T. Wiltshire, A. Lengeling, and M. Bucan, unpubl.). Pairwise analysis of the data gave a single linkage group for the three GABAA receptor loci and several SSLP markers (D5Mit151, D5Mit305, and D5Mit58) localized in the central portion of mouse chromosome 5 (Fig. 2). This analysis confirmed the location of the BAC contig on mouse chromosome 5. Furthermore, using Map Manager QT, we calculated the relative marker order along the chromosome by minimizing the number of occurred breaks and determined the most likely order: cen–D5Mit151–D5Buc12 (Gabrg1)–D5Buc18 (Gabra2)–Gabrb1–D5Mit58–tel (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

RH map of central mouse chromosome 5. The genetic map of mouse chromosome 5 with some selected loci and their position in cM (from the centromere) shown for orientation (Kozak and Stephenson 1998). Corresponding regions of homology in the human genome are denoted (http://www3.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Omim/Homology). The RH map of central mouse chromosome 5 from this work is shown in the enlarged area. Indicated are the positions of D5Mit markers and new D5Buc markers isolated from BAC clones with their specified insert end in brackets (Table 1). Pairwise lod scores and distances in centirays are indicated between neighboring loci.The RH mapping data (vector scores) have been deposited at the European Bioinformatics Institute (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/RHdb/index.html).

DISCUSSION

In this report we present a sequence-ready BAC contig spanning the cluster of genes encoding GABAA receptor subunits Gabra2, Gabrb1, and Gabrg1 located in the central portion of mouse chromosome 5. The established contig covers ∼1.3 Mb, as determined by the sizes of BACs corresponding to a minimal tiling path. The gene order of the three subunit genes on mouse chromosome 5 is the same as in all clusters that are composed of three subunits genes (β–α–γ/ε) and as observed in the human chromosome 15 cluster, α and β subunits are transcribed in opposite directions (Greger et al. 1995). In addition to the genes encoding GABAA subunits, this physical map includes three ESTs encoding genes of unknown function, with a widespread tissue expression pattern, and with no corresponding or mapped human ESTs. Although chromosomal localization for several GABAA receptor clusters has been determined in the mouse and human genome, a high-resolution physical map is only available for the GABAA clusters on human chromosomes 15 and 5 (Christian et al. 1998; Kostrzewa et al. 1998). Comparative sequence analysis of coding and noncoding regions of GABAA receptor genes, both within a cluster and between different clusters, in the mouse and humans may provide important information concerning the complex regulation of gene expression of members of this large gene family. For example, comprehensive expression analysis indicates overlapping expression of Gabra2, Gabrb1, and Gabrg1 in several regions of the brain, such as the neocortex, hippocampus, basal nuclei, amygdala, and red nucleus of the midbrain (for a summary, see Rabow et al. 1995). Comparative physical mapping and sequencing will shed light on the mechanisms involved in the tandem gene duplication events and transpositions that led to the clustered organization of the GABAA receptor genes. Further studies concerning the presence of an additional α subunit (α4) on human chromosome 4 (McLean et al. 1995), and apparent absence of the mouse ortholog in the immediate vicinity of the α2 subunit gene in the corresponding cluster on mouse chromosome 5, may indicate a dynamic evolution of this gene family. Furthermore, the presence or absence of nonrelated genes dispersed among the gene-family members in other clusters will provide useful insight into the timing of rearrangements during the evolution and origin of these genes in different species.

In the mouse, the Gabrg1–Gabra2–Gabrb1 cluster is located proximal to the cluster of classical developmental mutations—dominant spotting (W) and patch (Ph), which are caused by mutations or chromosomal rearrangements in the tyrosine kinase receptor genes Kit and Pdgfra (Reith and Bernstein 1991). In the human genome, orthologous genes are located in the centromeric portion of chromosome 4, with the GABRA2, GABRB1, and GABRG1 loci mapped to the short arm (4p12–p13), and the KIT–PDGFRA cluster on the long arm (4q12–q13) (http://www3.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Omim/Homology/). Sequence analysis of the region between the two clusters in the mouse should aid in determining sequences surrounding the centromere of human chromosome 4.

The construction of this contig coincides with the launching of an initiative to generate a working draft of the mouse genome sequence by 2003 (Battey et al. 1999). This effort will employ a random strategy for selection of clones that will not involve extensive mapping efforts and construction of sequence-ready BAC contigs prior to sequencing. In the initial phase, however, established contigs such as this, spanning the GABAA cluster, will provide a useful template for the generation of long stretches of contiguous genomic sequence in the mouse. A common C57BL/6J BAC library has been designated as the reference library in this sequencing effort (http://bacpac.med.buffalo.edu/mouse_bac.html). Our data add to the initial evaluation of the high quality of this library, its uniform coverage, and a large average insert size (197 kb). Although the comparative sequence analysis of the GABAA clusters will provide important information concerning functional domains in the coding and noncoding regions, BAC clones containing individual GABAA subunit genes will provide immediate resources for functional studies.

METHODS

Isolation and Processing of BAC Clones

BAC clones were isolated by hybridization of probes to high-density library filters from three different BAC libraries: 129/Sv (Research Genetics, Huntsville, AL), RPCI-22 129/SvEvTACfBr, and RPCI-23 C57BL/6J BAC libraries (K. Osoegawa, M. Tateno, and P. de Jong, in prep.; for more information, see http://bacpac.med.buffalo.edu/mouse_bac.html). BAC libraries were initially screened with probes from rat Gabra2 cDNA (Khrestchatisky et al. 1991), rat Gabrg1 cDNA (M. Khrestchatisky and A. Tobin, unpubl.), and the mouse Gabrb1 cDNA (Nagle et al. 1995), and subsequent screenings used STSs generated from BAC-end sequences. All radioactive labeling of probes used standard random-primed methods (Feinberg and Vogelstein 1983).

All BACs isolated were arrayed as colony dot blots in a 96-well format. BACs were grown overnight in 100 μl of Luria broth (LB)/chloramphenicol, spotted onto nylon filters, and then grown for 8 hr on LB agar plates. Filters were processed using alkaline lysis and Proteinase K/Sarkosyl treatment (see http://www.resgen.com/depts/rnd/rapid.html).

BAC DNA was prepared by standard alkaline lysis methods (Sambrook et al. 1989) from 5 ml of overnight culture and resuspended in 40 μl of TE buffer. Miniprep DNA (5 μl) was digested immediately in a total volume of 20 μl with 5 units of NotI enzyme (New England Biolabs, Inc., Beverly, MA) for 2 hr at 37°C. Samples were loaded on a 1% agarose gel in 0.5% Tris-borate–EDTA (TBE) and subjected to PFGE (Bio-Rad CHEF DR II) for 16 hr at 6 V/cm, 15°C with a switching interval from 5 sec to 15 sec. BAC insert sizes were assigned from ethidium bromide-stained gels using AlphEase software and an Alpha-Imager 2000 gel-documentation system (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA). EcoRI digests of freshly prepared miniprep DNA were also used to fingerprint clones according to the methods of Marra et al. (1997). Clone overlap analysis was carried out manually.

Sequencing of BAC-Insert Ends

BAC DNA for sequencing was prepared from 200 ml of overnight culture according to the modified protocol for BACs using P100 midi-prep columns (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA). Automated dideoxy-terminator cycle sequencing was carried out with SP6 and T7 primers on BAC DNA (2 μg of DNA in a 20-μl reaction) using ABI Big Dye Terminator sequencing chemistry with Taq FS polymerase from Applied BioSystems (Foster City, CA). Reaction products were purified by G50 spin columns and analyzed on ABI 377 automated sequencers (DNA Sequencing Facility, Department of Genetics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia).

Development of New STSs and Marker Content Mapping

BAC end sequence was assessed for development of new STS markers. To determine rodent specific and low complexity repeats, nucleotide sequences were analyzed using RepeatMasker (http://ftp.genome.washington.edu/cgi-bin/RepeatMasker). Primer 3.0 software (http://www-genome.wi.mit.edu/cgi-bin/primer/primer3.cgi) was used for selection of PCR primers. STS content mapping of BACs was determined by hybridization of specific probes to colony dot blots. PCR was performed with diluted mini-prep BAC DNA in 15-μl reactions consisting of 1× buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl at pH 8.3, 50 mm KCl, and 2.5 mm MgCl2), 0.2 mm each dNTP, 1 μm each STS primer, and 0.5 unit of Taq polymerase (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) under the following conditions: 94°C for 30 sec, annealing for 30 sec (temperatures listed in Table 1), 72°C for 30 sec, for 35 cycles.

Screening of cDNA Libraries

The rat Gabrg1 cDNA probe (1200-bp EcoRV fragment) was used to screen an arrayed mouse olfactory bulb cDNA library (Resource Center/Primary Database of the German Human Genome Project, Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics, Berlin-Charlottenburg, Germany). Clone UCDMp608P0343Q2 was isolated, sequenced, and used to design 5′- and 3′-specific PCR assays for the mouse Gabrg1 gene.

RH Mapping

T31 RH panel DNAs (Research Genetics, Huntsville, AL) were diluted to 3 ng/μl and 3 μl of each cell hybrid clone DNA was used in PCRs. PCR reagents and conditions were previously described. Primers were initially tested on mouse and hamster DNA controls, prior to the analysis of 100-cell hybrid lines. PCR amplicons were run on 2% agarose gels and the presence or absence of PCR fragments were scored. For each marker the T31 RH panel was typed twice. Data analysis was performed with Map Manager QTb 27 ppc. Distances between neighboring loci (in centirays) were calculated with the RH2PT function of the RH Map program (Lunetta et al. 1996). The RH mapping data (vector scores) have been deposited at the European Bioinformatics Institute (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/RHdb/index.html).

Acknowledgments

We thank Michel Khrestchatisky and Allan Tobin for the rat Gabrga2 and Gabrg1 cDNA probes, Lisa Tarantino and Ali Alavizadeh for help with the RH mapping analysis, Ariel Soiffer for the technical assistance in the initial phase of this project, Nadja Pohl for assistance with the cDNA screen, Lisa Stubbs and Mark LaLande for discussions on gene order in GABAA clusters, and Tom Ferraro and Lisa Tarantino for comments on the manuscript. These studies were supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (HD 28410 and MH 57855).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL bucan@pobox.upenn.edu; FAX (215) 573-2041.

REFERENCES

- Battey J, Jordan E, Cox D, Dove W. An action plan for mouse genomics. Nat Genet. 1999;21:73–75. doi: 10.1038/5012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bormann J, Hamill O P, Sakmann B. Mechanism of anion permeation through channels gated by glycine and gamma-aminobutyric acid in mouse cultured spinal neurones. J Physiol. 1987;385:243–286. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd Y, Blair HJ, Cunliffe P, Denny P, Gormally E, Herman GE. Encyclopedia of the mouse genome VII. Mouse chromosome X. Mamm Genome. 1998;8:361–377. doi: 10.1007/s003359900665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Kayal AR, Shumate MD, Jin H, Rikhter TY, Coulter DA. Selective changes in single cell GABAA receptor subunit expression and function in temporal lobe epilepsy. Nat Med. 1998;4:1166–1172. doi: 10.1038/2661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckle VJ, Fujita N, Ryder-Cook AS, Derry JM, Barnard PJ, Lebo RV, Schofield PR, Seeburg PH, Bateson AN, Darlison MG. Chromosomal localization of GABAA receptor subunit genes: Relationship to human genetic disease. Neuron. 1989;3:647–654. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90275-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt DR, Kamatchi GL. GABAA receptor subtypes: From pharmacology to molecular biology. FASEB J. 1991;5:2916–2923. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.5.14.1661244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian SL, Bhatt NK, Martin SA, Sutcliffe JS, Kubota T, Huang B, Mutirangura A, Chinault AC, Beaudet AL, Ledbetter DH. Integrated YAC contig map of the Prader-Willi/Angelman region on chromosome 15q11-q13 with average STS spacing of 35 kb. Genome Res. 1998;8:146–157. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.2.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culiat CT, Stubbs LJ, Montgomery CS, Russell LB, Rinchik EM. Phenotypic consequences of deletion of the γ3, α5, or β3 subunit of the type A gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1994;91:2815–2818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutting GR, Curristin S, Zoghbi H, O’Hara B, Seldin MF, Uhl GR. Identification of a putative gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor subunit rho2 cDNA and colocalization of the genes encoding rho2 (GABRR2) and rho1 (GABRR1) to human chromosome 6q14-q21 and mouse chromosome 4. Genomics. 1992;12:801–806. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(92)90312-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danciger M, Farber DB, Kozak CA. Genetic mapping of three GABAA receptor-subunit genes in the mouse. Genomics. 1993;16:361–365. doi: 10.1006/geno.1993.1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg AP, Vogelstein B. A technique for radiolabeling DNA restriction endonuclease fragments to high specific activity. Anal Biochem. 1983;132:6–13. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett KM, Haque D, Berry D, Niekrasz I, Gan J, Rotter A, Seale TW. The GABAA receptor α6 subunit gene (Gabra6) is tightly linked to the α1-γ2 subunit cluster on mouse chromosome 11. Mol Brain Res. 1997;45:133–137. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(96)00290-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glatt K, Glatt H, Lalande M. Structure and organization of GABRB3 and GABRA5. Genomics. 1997;41:63–69. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greger V, Knoll JH, Woolf E, Glatt K, Tyndale RF, DeLorey TM, Olsen RW, Tobin AJ, Sikela JM, Nakatsu Y. The gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor γ3 subunit gene (GABRG3) is tightly linked to the α5 subunit gene (GABRA5) on human chromosome 15q11-q13 and is transcribed in the same orientation. Genomics. 1995;26:258–264. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(95)80209-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamatchi GL, Kofuji P, Wang JB, Fernando JC, Liu Z, Mathura JR, Jr, Burt DR. GABAA receptor β1, β2, and β3 subunits: Comparisons in DBA/2J and C57BL/6J mice. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1261:134–142. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(95)00009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaupmann K, Huggel K, Heid J, Flor PJ, Bischoff S, Mickel SJ, McMaster G, Angst C, Bittiger H, Froestl W, Bettler B. Expression cloning of GABAB receptors uncovers similarity to metabotropic glutamate receptors. Nature. 1997;386:239–246. doi: 10.1038/386239a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaupmann K, Malitschek B, Schuler V, Heid J, Froestl W, Beck P, Mosbacher J, Bischoff S, Kulik A, Shigemoto R, Karschin A, Bettler B. GABAB-receptor subtypes assemble into functional heteromeric complexes. Nature. 1998;396:683–687. doi: 10.1038/25360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khestchatisky M, MacLennan AJ, Tillakaratne NJ, Chiang MY, Tobin AJ. Sequence and regional distribution of the mRNA encoding the α2 polypeptide of rat gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptors. J Neurochem. 1991;56:1717–1722. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb02072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkness EF, Kusiak JW, Fleming JT, Menninger J, Gocayne JD, Ward DC, Venter JC. Isolation, characterization, and localization of human genomic DNA encoding the beta 1 subunit of the GABAA receptor (GABRB1) Genomics. 1991;10:985–995. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(91)90189-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostrzewa M, Krings BW, Dixon MJ, Eppelt K, Kohler A, Grady DL, Steinberger D, Fairweather ND, Moyzis RK, Monaco AP, Muller U. Integrated physical and transcript map of 5q31.3-qter. Eur J Hum Genet. 1998;6:266–274. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak CA, Stephenson DA. Encyclopedia of the mouse genome VII. Mouse chromosome 5. Mamm Genome. 1998;8:S91–113. doi: 10.1007/s003359900650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ML, Chatterjee A, Pragliola A, Worley KC, Wehnert M, Zhuchenko O, Smith RF, Lee CC, Herman GE. A comparative transcription map of the murine bare patches (Bpa) and striated (Str) critical regions and human Xq28. Genome Res. 1996;6:465–477. doi: 10.1101/gr.6.6.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunetta KL, Boehnke M, Lange K, Cox DR. Selected locus and multiple panel models for radiation hybrid mapping. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;59:717–725. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marra MA, Kucaba TA, Dietrich NL, Green ED, Brownstein B, Wilson RK, McDonald KM, Hillier LW, McPherson JD, Waterston RH. High-throughput fingerprint analysis of large-insert clones. Genome Res. 1997;7:1072–1084. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.11.1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy LC, Terrett J, Davis ME, Knights CJ, Smith AL, Critcher R, Schmitt K, Hudson J, Spurr NK, Goodfellow PN. A first-generation whole genome-radiation hybrid map spanning the mouse genome. Genome Res. 1997;7:1153–1161. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.12.1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean PJ, Farb DH, Russek SJ. Mapping of the α4 subunit gene (GABRA4) to human chromosome 4 defines an α2-α4-β1-γ1 gene cluster: Further evidence that modern GABAA receptor gene clusters are derived from an ancestral cluster. Genomics. 1995;26:580–586. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(95)80178-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagle DL, Kozak CA, Mano H, Chapman VM, Bucan M. Physical mapping of the Tec and Gabrb1 loci reveals that the Wsh mutation on mouse chromosome 5 is associated with an inversion. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:2073–2079. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.11.2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatsu Y, Tyndale RF, DeLorey TM, Durham-Pierre D, Gardner JM, McDanel HJ, Nguyen Q, Wagstaff J, Lalande M, Sikela JM. A cluster of three GABAA receptor subunit genes is deleted in a neurological mutant of the mouse p locus. Nature. 1993;364:448–450. doi: 10.1038/364448a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabow LE, Russek SJ, Farb DH. From ion currents to genomic analysis: Recent advances in GABAA receptor research. Synapse. 1995;21:189–274. doi: 10.1002/syn.890210302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reith AD, Bernstein A. Molecular biology of the W and Steel loci. In: Davies KE, Tilghman SM, editors. Genome analysis: Genes and phenotypes. Vol. 3. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1991. pp. 105–133. [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: A laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Seeburg PH, Wisden W, Verdoorn TA, Pritchett DB, Werner P, Herb A, Luddens H, Sprengel R, Sakmann B. The GABAA receptor family: Molecular and functional diversity. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1990;55:29–40. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1990.055.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiah IS, Yatham LN. GABA function in mood disorders: An update and critical review. Life Sci. 1998;63:1289–1303. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JB, Kofuji P, Fernando JC, Moss SJ, Huganir RL, Burt DR. The α1, α2, and α3 subunits of GABAA receptors: Comparison in seizure-prone and -resistant mice and during development. J Mol Neurosci. 1992;3:177–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox AS, Warrington JA, Gardiner K, Berger R, Whiting P, Altherr MR, Wasmuth JJ, Patterson D, Sikela JM. Human chromosomal localization of genes encoding the γ1 and γ2 subunits of the gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor indicates that members of this gene family are often clustered in the genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1992;89:5857–5861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.5857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilke K, Gaul R, Klauck SM, Poustka A. A gene in human chromosome band Xq28 (GABRE) defines a putative new subunit class of the GABAA neurotransmitter receptor. Genomics. 1997;45:1–10. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisden W, Seeburg PH. GABAA receptor channels: From subunits to functional entities. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1992;2:263–269. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(92)90113-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]