Abstract

The polyvagal theory describes an autonomic nervous system that is influenced by the central nervous system, sensitive to afferent influences, characterized by an adaptive reactivity dependent on the phylogeny of the neural circuits, and interactive with source nuclei in the brainstem regulating the striated muscles of the face and head. The theory is dependent on accumulated knowledge describing the phylogenetic transitions in the vertebrate autonomic nervous system. Its specific focus is on the phylogenetic shift between reptiles and mammals that resulted in specific changes to the vagal pathways regulating the heart. As the source nuclei of the primary vagal efferent pathways regulating the heart shifted from the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus in reptiles to the nucleus ambiguus in mammals, a face–heart connection evolved with emergent properties of a social engagement system that would enable social interactions to regulate visceral state.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES ON THE AUTONOMIC NERVOUS SYSTEM

Central nervous system regulation of visceral organs is the focus of several historic publications that have shaped the texture of physiological inquiry. For example, in 1872 Darwin acknowledged the dynamic neural relationship between the heart and the brain:

. . .when the heart is affected it reacts on the brain; and the state of the brain again reacts through the pneumo-gastric [vagus] nerve on the heart; so that under any excitement there will be much mutual action and reaction between these, the two most important organs of the body.1

Although Darwin acknowledged the bidirectional communication between the viscera and the brain, subsequent formal description of the autonomic nervous system (eg, by Langley2) minimized the importance of central regulatory structures and afferents. Following Langley, medical and physiological research tended to focus on the peripheral motor nerves of the autonomic nervous sytem, with a conceptual emphasis on the paired antagonism between sympathetic and parasympathetic efferent pathways on the target visceral organs. This focus minimized interest in both afferent pathways and the brainstem areas that regulate specific efferent pathways.

The early conceptualization of the vagus focused on an undifferentiated efferent pathway that was assumed to modulate “tone” concurrently to several target organs. Thus, brainstem areas regulating the supradiaphragmatic (eg, myelinated vagal pathways originating in the nucleus ambiguus and terminating primarily above the diaphragm) were not functionally distinguished from those regulating the subdiaphragmatic (eg, unmyelinated vagal pathways originating in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus and terminating primarily below the diaphragm). Without this distinction, research and theory focused on the paired antagonism between the parasympathetic and sympathetic innervation to target organs. The consequence of an emphasis on paired antagonism was an acceptance in physiology and medicine of global constructs such as autonomic balance, sympathetic tone, and vagal tone.

More than 50 years ago, Hess proposed that the autonomic nervous system was not solely vegetative and automatic but was instead an integrated system with both peripheral and central neurons.3 By emphasizing the central mechanisms that mediate the dynamic regulation of peripheral organs, Hess anticipated the need for technologies to continuously monitor peripheral and central neural circuits involved in the regulation of visceral function.

THE VAGAL PARADOX

In 1992, I proposed that an estimate of vagal tone, derived from measuring respiratory sinus arrhythmia, could be used in clinical medicine as an index of stress vulnerability.4 Rather than using the descriptive measures of heart rate variability (ie, beat-to-beat variability) frequently used in obstetrics and pediatrics, the paper emphasized that respiratory sinus arrhythmia has a neural origin and represents the tonic functional outflow from the vagus to the heart (ie, cardiac vagal tone). Thus, it was proposed that respiratory sinus arrhythmia would provide a more sensitive index of health status than a more global measure of beat-to-beat heart rate variability reflecting undetermined neural and nonneural mechanisms. The paper presented a quantitative approach that applied time-series analyses to extract the amplitude of respiratory sinus arrhythmia as a more accurate index of vagal activity. The article provided data demonstrating that healthy full-term infants had respiratory sinus arrhythmia of significantly greater amplitude than did preterm infants. This idea of using heart rate patterns to index vagal activity was not new, having been reported as early as 1910 by Hering.5 Moreover, contemporary studies have reliably reported that vagal blockade via atropine depresses respiratory sinus arrhythmia in mammals.6,7

In response to this article,4 I received a letter from a neonatologist who wrote that, as a medical student, he learned that vagal tone could be lethal. He argued that perhaps too much of a good thing (ie, vagal tone) could be bad. He was referring, of course, to the clinical risk of neurogenic bradycardia. Bradycardia, when observed during delivery, may be an indicator of fetal distress. Similarly, bradycardia and apnea are important indicators of risk for the newborn.

My colleagues and I further investigated this perplexing observation by studying the human fetus during delivery. We observed that fetal bradycardia occurred only when respiratory sinus arrhythmia was depressed (ie, a respiratory rhythm in fetal heart rate is observable even in the absence of the large chest wall movements associated with breathing that occur postpartum).8 This raised the question of how vagal mechanisms could mediate both respiratory sinus arrhythmia and bradycardia, as one is protective and the other is potentially lethal. This inconsistency became the “vagal paradox” and served as the motivation behind the polyvagal theory.

With regard to the mechanisms mediating brady-cardia and heart rate variability, there is an obvious inconsistency between data and physiological assumptions. Physiological models assume vagal regulation of both chronotropic control of the heart (ie, heart rate) and the amplitude of respiratory sinus arrhythmia.9,10 For example, it has been reliably reported that vagal cardio-inhibitory fibers to the heart have consistent functional properties characterized by bradycardia to neural stimulation and a respiratory rhythm.9 However, although there are situations in which both measures covary (eg, during exercise and cholinergic blockade), there are other situations in which the measures appear to reflect independent sources of neural control (eg, bradycardic episodes associated with hypoxia, vasovagal syncope, and fetal distress). In contrast to these observable phenomena, researchers continue to argue for a covariation between these two parameters. This inconsistency, based on an assumption of a single central vagal source, is what I have labeled the vagal paradox.

THE POLYVAGAL THEORY: THREE PHYLOGENETIC RESPONSE SYSTEMS

Investigation of the phylogeny of the vertebrate autonomic nervous system provides an answer to the vagal paradox. Research in comparative neuroanatomy and neurophysiology has identified two branches of the vagus, with each branch supporting different adaptive functions and behavioral strategies. The vagal output to the heart from one branch is manifested in respiratory sinus arrhythmia, and the output from the other branch is manifested in bradycardia and possibly the slower rhythms in heart rate variability. Although the slower rhythms have been assumed to have a sympathetic influence, they are blocked by atropine.7

The polyvagal theory7,11–15 articulates how each of three phylogenetic stages in the development of the vertebrate autonomic nervous system is associated with a distinct autonomic subsystem that is retained and expressed in mammals. These autonomic subsystems are phylogenetically ordered and behaviorally linked to social communication (eg, facial expression, vocalization, listening), mobilization (eg, fight–flight behaviors), and immobilization (eg, feigning death, vasovagal syncope, and behavioral shutdown).

The social communication system (ie, social engagement system; see below) involves the myelinated vagus, which serves to foster calm behavioral states by inhibiting sympathetic influences to the heart and dampening the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis.16 The mobilization system is dependent on the functioning of the sympathetic nervous system. The most phylo-genetically primitive component, the immobilization system, is dependent on the unmyelinated vagus, which is shared with most vertebrates. With increased neural complexity resulting from phylogenetic development, the organism's behavioral and affective repertoire is enriched. The three circuits can be conceptualized as dynamic, providing adaptive responses to safe, dangerous, and life-threatening events and contexts.

Only mammals have a myelinated vagus. Unlike the unmyelinated vagus, originating in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus with pre- and postganglionic muscarinic receptors, the mammalian myelinated vagus originates in the nucleus ambiguus and has preganglionic nicotinic receptors and postganglionic muscarinic receptors. The unmyelinated vagus is shared with other vertebrates, including reptiles, amphibians, teleosts, and elasmobranchs.

We are now investigating the possibility of extracting different features of the heart rate pattern to dynamically monitor the two vagal systems. Preliminary studies in our laboratory support this possibility. In these studies we have blocked the nicotinic preganglionic receptors with hexamethonium and the muscarinic receptors with atropine. The data were collected from the prairie vole,17 which has a very high ambient vagal tone. These preliminary data demonstrated that, in several animals, nicotinic blockade selectively removes respiratory sinus arrhythmia without dampening the amplitude of the lower frequencies in heart rate variability. In contrast, blocking the muscarinic receptors with atropine removes both the low and respiratory frequencies.

CONSISTENCY WITH JACKSONIAN DISSOLUTION

The three circuits are organized and respond to challenges in a phylogenetically determined hierarchy consistent with the Jacksonian principle of dissolution. Jackson proposed that in the brain, higher (ie, phylogenetically newer) neural circuits inhibit lower (ie, phylogenetically older) neural circuits and “when the higher are suddenly rendered functionless, the lower rise in activity.”18 Although Jackson proposed dissolution to explain changes in brain function due to damage and illness, the polyvagal theory proposes a similar phylogenetically ordered hierarchical model to describe the sequence of autonomic response strategies to challenges.

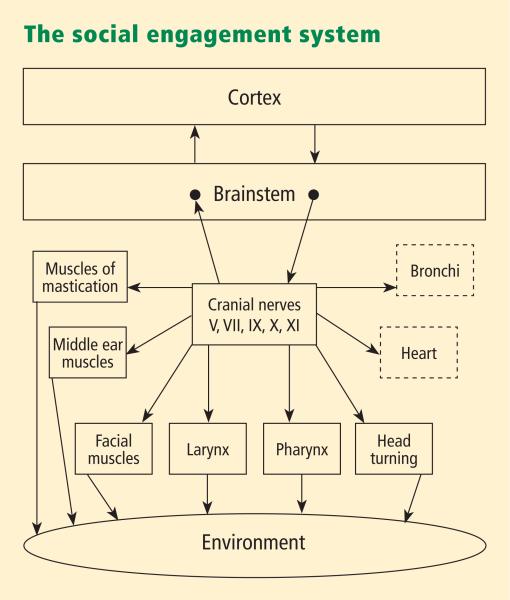

Functionally, when the environment is perceived as safe, two important features are expressed. First, bodily state is regulated in an efficient manner to promote growth and restoration (eg, visceral homeostasis). This is done through an increase in the influence of mammalian myelinated vagal motor pathways on the cardiac pacemaker that slows the heart, inhibits the fight–flight mechanisms of the sympathetic nervous system, dampens the stress response system of the HPA axis (eg, cortisol), and reduces inflammation by modulating immune reactions (eg, cyto kines). Second, through the process of evolution, the brainstem nuclei that regulate the myelinated vagus became integrated with the nuclei that regulate the muscles of the face and head. This link results in the bidirectional coupling between spontaneous social engagement behaviors and bodily states. Specifically, an integrated social engagement system emerged in mammals when the neural regulation of visceral states that promote growth and restoration (via the myelinated vagus) was linked neuroanatomically and neurophysiologically with the neural regulation of the muscles controlling eye gaze, facial expression, listening, and prosody (Figure 1; see Porges7 for review).

FIGURE 1.

The social engagement system consists of a somatomotor component (solid blocks) and a visceromotor component (dashed blocks). The somatomotor component involves special visceral efferent pathways that regulate the striated muscles of the face and head, while the visceromotor component involves the myelinated vagus that regulates the heart and bronchi.7

The human nervous system, similar to that of other mammals, evolved not solely to survive in safe environments but also to promote survival in dangerous and life-threatening contexts. To accomplish this adaptive flexibility, the human nervous system retained two more primitive neural circuits to regulate defensive strategies (ie, fight–flight and death-feigning behaviors). It is important to note that social behavior, social communication, and visceral homeostasis are incompatible with the neurophysiological states and behaviors promoted by the two neural circuits that support defense strategies. Thus, via evolution, the human nervous system retains three neural circuits, which are in a phylogenetically organized hierarchy. In this hierarchy of adaptive responses, the newest circuit is used first; if that circuit fails to provide safety, the older circuits are recruited sequentially.

Investigation of the phylogeny of regulation of the vertebrate heart11,12,19,20 has led to extraction of four principles that provide a basis for testing of hypotheses relating specifi c neural mechanisms to social engagement, fight–flight, and death-feigning behaviors:

There is a phylogenetic shift in the regulation of the heart from endocrine communication to unmyelinated nerves and finally to myelinated nerves.

There is a development of opposing neural mechanisms of excitation and inhibition to provide rapid regulation of graded metabolic output.

A face–heart connection evolved as source nuclei of vagal pathways shifted ventrally from the older dorsal motor nucleus to the nucleus ambiguus. This resulted in an anatomical and neurophysiological linkage between neural regulation of the heart via the myelinated vagus and the special visceral efferent pathways that regulate the striated muscles of the face and head, forming an integrated social engagement system (Figure 1; for more details, see Porges7,15).

With increased cortical development, the cortex exhibits greater control over the brainstem via direct (eg, corticobulbar) and indirect (eg, corticoreticular) neural pathways originating in motor cortex and terminating in the source nuclei of the myelinated motor nerves emerging from the brainstem (eg, specifi c neural pathways embedded within cranial nerves V, VII, IX, X, and XI), controlling visceromotor structures (ie, heart, bronchi) as well as somatomotor structures (muscles of the face and head).

NEUROCEPTION: CONTEXTUAL CUEING OF ADAPTIVE, MALADAPTIVE PHYSIOLOGICAL STATES

To effectively switch from defensive to social engagement strategies, the mammalian nervous system needs to perform two important adaptive tasks: (1) assess risk, and (2) if the environment is perceived as safe, inhibit the more primitive limbic structures that control fight, flight, or freeze behaviors.

Any stimulus that has the potential for increasing an organism's experience of safety has the potential of recruiting the evolutionarily more advanced neural circuits that support the prosocial behaviors of the social engagement system.

The nervous system, through the processing of sensory information from the environment and from the viscera, continuously evaluates risk. Since the neural evaluation of risk does not require conscious awareness and may involve subcortical limbic structures,21 the term neuroception22 was introduced to emphasize a neural process, distinct from perception, that is capable of distinguishing environmental (and visceral) features that are safe, dangerous, or life-threatening. In safe environments, autonomic state is adaptively regulated to dampen sympathetic activation and to protect the oxygen-dependent central nervous system, especially the cortex, from the metabolically conservative reactions of the dorsal vagal complex. However, how does the nervous system know when the environment is safe, dangerous, or life-threatening, and which neural mechanisms evaluate this risk?

Environmental components of neuroception

Neuroception represents a neural process that enables humans and other mammals to engage in social behaviors by distinguishing safe from dangerous contexts. Neuroception is proposed as a plausible mechanism mediating both the expression and the disruption of positive social behavior, emotion regulation, and visceral homeostasis.7,22 Neuroception might be triggered by feature detectors involving areas of temporal cortex that communicate with the central nucleus of the amygdala and the periaqueductal gray, since limbic reactivity is modulated by temporal cortex responses to the intention of voices, faces, and hand movements. Thus, the neuroception of familiar individuals and individuals with appropriately prosodic voices and warm, expressive faces translates into a social interaction promoting a sense of safety.

In most individuals (ie, those without a psychiatric disorder or neuropathology), the nervous system evaluates risk and matches neurophysiological state with the actual risk of the environment. When the environment is appraised as being safe, the defensive limbic structures are inhibited, enabling social engagement and calm visceral states to emerge. In contrast, some individuals experience a mismatch and the nervous system appraises the environment as being dangerous even when it is safe. This mismatch results in physiological states that support fight, flight, or freeze behaviors, but not social engagement behaviors. According to the theory, social communication can be expressed efficiently through the social engagement system only when these defensive circuits are inhibited.

Other contributors to neuroception

The features of risk in the environment do not solely drive neuroception. Afferent feedback from the viscera provides a major mediator of the accessibility of prosocial circuits associated with social engagement behaviors. For example, the polyvagal theory predicts that states of mobilization would compromise our ability to detect positive social cues. Functionally, visceral states color our perception of objects and others. Thus, the same features of one person engaging another may result in a range of outcomes, depending on the physiological state of the target individual. If the person being engaged is in a state in which the social engagement system is easily accessible, the reciprocal prosocial interactions are likely to occur. However, if the individual is in a state of mobilization, the same engaging response might be responded to with the asocial features of withdrawal or aggression. In such a state, it might be very difficult to dampen the mobilization circuit and enable the social engagement system to come back on line.

The insula may be involved in the mediation of neuroception, since it has been proposed as a brain structure involved in conveying the diffuse feedback from the viscera into cognitive awareness. Functional imaging experiments have demonstrated that the insula plays an important role in the experience of pain and the experience of several emotions, including anger, fear, disgust, happiness, and sadness. Critchley proposes that internal body states are represented in the insula and contribute to states of subjective feeling, and he has demonstrated that activity in the insula correlates with interoceptive accuracy.23

SUMMARY

The polyvagal theory proposes that the evolution of the mammalian autonomic nervous system provides the neurophysiological substrates for adaptive behavioral strategies. It further proposes that physiological state limits the range of behavior and psychological experience. The theory links the evolution of the autonomic nervous system to affective experience, emotional expression, facial gestures, vocal communication, and contingent social behavior. In this way, the theory provides a plausible explanation for the reported covariation between atypical autonomic regulation (eg, reduced vagal and increased sympathetic influences to the heart) and psychiatric and behavioral disorders that involve difficulties in regulating appropriate social, emotional, and communication behaviors.

The polyvagal theory provides several insights into the adaptive nature of physiological state. First, the theory emphasizes that physiological states support different classes of behavior. For example, a physiological state characterized by a vagal withdrawal would support the mobilization behaviors of fight and flight. In contrast, a physiological state characterized by increased vagal influence on the heart (via myelinated vagal pathways originating in the nucleus ambiguus) would support spontaneous social engagement behaviors. Second, the theory emphasizes the formation of an integrated social engagement system through functional and structural links between neural control of the striated muscles of the face and the smooth muscles of the viscera. Third, the polyvagal theory proposes a mechanism—neuroception—to trigger or to inhibit defense strategies.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Porges reported that he has no financial interests or relationships that pose a potential conflict of interest with this article. The preparation of this manuscript was supported, in part, by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (HD 053570).

REFERENCES

- 1.Darwin C. The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals. D Appleton; New York, NY: 1872. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langley JN. The Autonomic Nervous System. Heffer & Sons; Cambridge, England: 1921. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hess WR. Diencephalon, Autonomic and Extrapyramidal Functions. Grune & Stratton; New York, NY: 1954. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Porges SW. Vagal tone: a physiologic marker of stress vulnerability. Pediatrics. 1992;90:498–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hering HE. A functional test of heart vagi in man. Menschen Munchen Medizinische Wochenschrift. 1910;57:1931–1933. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Porges SW. Respiratory sinus arrhythmia: physiological basis, quantitative methods, and clinical implications. In: Grossman P, Janssen K, Vaitl D, editors. Cardiorespiratory and Cardiosomatic Psychophysiology. Plenum; New York, NY: 1986. pp. 101–115. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Porges SW. The polyvagal perspective. Biol Psychol. 2007;74:116–143. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reed SF, Ohel G, David R, Porges SW. A neural explanation of fetal heart rate patterns: a test of the polyvagal theory. Dev Psychobiol. 1999;35:108–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jordan D, Khalid ME, Schneiderman N, Spyer KM. The location and properties of preganglionic vagal cardiomotor neurones in the rabbit. Pfl ugers Arch. 1982;395:244–250. doi: 10.1007/BF00584817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katona PG, Jih F. Respiratory sinus arrhythmia: noninvasive measure of parasympathetic cardiac control. J Appl Physiol. 1975;39:801–805. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1975.39.5.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Porges SW. Orienting in a defensive world: mammalian modifi cations of our evolutionary heritage—a polyvagal theory. Psychophysiology. 1995;32:301–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1995.tb01213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Porges SW. Emotion: An evolutionary by-product of the neural regulation of the autonomic nervous system. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;807:62–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb51913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Porges SW. Love: An emergent property of the mammalian autonomic nervous system. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998;23:837–861. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(98)00057-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Porges SW. The polyvagal theory: phylogenetic substrates of a social nervous system. Int J Psychophysiol. 2001;42:123–146. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(01)00162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Porges SW. Social engagement and attachment: a phylogenetic perspective. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1008:31–47. doi: 10.1196/annals.1301.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bueno L, Gue M, Fargeas MJ, Alvinerie M, Junien JL, Fioramonti J. Vagally mediated inhibition of acoustic stress-induced cortisol release by orally administered kappa-opioid substances in dogs. Endocrinology. 1989;124:1788–1793. doi: 10.1210/endo-124-4-1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grippo AJ, Lamb DG, Carter CS, Porges SW. Cardiac regulation in the socially monogamous prairie vole. Physiol Behav. 2007;90:386–393. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jackson JH. Evolution and dissolution of the nervous system. In: Taylor J, editor. Selected Writings of John Hughlings Jackson. Stapes Press; London: 1958. pp. 45–118. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morris JL, Nilsson S. The circulatory system. In: Nilsson S, Holmgren S, editors. Comparative Physiology and Evolution of the Autonomic Nervous System. Harwood Academic Publishers; Chur, Switzerland: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor EW, Jordan D, Coote JH. Central control of the cardiovascular and respiratory systems and their interactions in vertebrates. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:855–916. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.3.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morris JS, Ohman A, Dolan RJ. A subcortical pathway to the right amygdala mediating “unseen” fear. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:1680–1685. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Porges SW. Neuroception: a subconscious system for detecting threat and safety. Zero to Three: Bulletin of the National Center for Clinical Infant Programs. 2004;24(5):19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Critchley HD. Neural mechanisms of autonomic, affective, and cognitive integration. J Comp Neurol. 2005;493:154–166. doi: 10.1002/cne.20749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]