Abstract

Pulmonary arterial hypertension is a disease characterized by a sustained increase in pulmonary arterial pressure leading to right heart failure. Current treatments focus on endothelial dysfunction and an aberrant regulatory pathway for vascular tone. Unfortunately, a large proportion of patients are unresponsive to conventional vasodilator therapy. Investigations are ongoing into the effects of experimental therapies targeting the signal transduction pathway that mediates vasodilation. Here, we briefly discuss the pathophysiology of pulmonary hypertension and endothelial dysfunction, along with current treatments. We then present a focused review of recent animal studies and human trials examining the use of activators and stimulators of soluble guanylate cyclase for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension.

Keywords: activators, endothelial dysfunction, nitric oxide, pulmonary hypertension, soluble guanylate cyclase, stimulators

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a disease characterized by a persistent increase in pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP) accompanied by pulmonary vascular damage and right heart failure. The 1-year incidence mortality associated with PAH is 15% [1]. The vascular damage manifests through abnormal migration and proliferation of the muscular layer of the pulmonary arteries, increased fibroblast proliferation, fibrosis within the tissue architecture and widespread pulmonary endothelial dysfunction [2]. An increase in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) causes sustained elevation of PAP, increased afterload on the right heart, and eventual right heart failure (cor pulmonale). Right ventricular function is strongly predictive of prognosis in patients with PAH [3]. While vasoconstriction may be the initial culprit for increased PAP, remodeling and proliferation within the vasculature is believed to be responsible for the chronic stages.

Endothelial dysfunction within the pulmonary vasculature is a hallmark of PAH. It is well known that patients with PAH have reduced expression of nitric oxide synthase (NOS), the enzyme necessary for converting l-arginine to the vasodilator, nitric oxide (NO) [4]. The prostacyclin pathway, which has vasodilatory, antiplatelet and cytoprotective functions, has also been shown to be downregulated in PAH, with decreased prostacyclin synthase expression [5–8]. Similarly, an increase in the release of the vasoconstrictor thromboxane-A2 (TXA2) has been reported in idiopathic PAH as well as pulmonary hypertension (PH) resulting from pre-existing medical conditions or side effects of pharmacotherapies [9]. Therefore, many treatments are targeted at reversal of the sustained vasoconstriction. These treatments include phosphodiesterase type-5 (PDE-5) inhibitors, prostacyclins and endothelin antagonists [10]. Unfortunately, a large proportion of patients are unresponsive to current vasodilator therapies [1].

Chronic thromboembolic PH (CTEPH) is a form of PH involving the organization of thrombi within the pulmonary vasculature as the result of repeated pulmonary thromboembolism. Similar to PAH, CTEPH leads to a gradual increase in PVR, PAP and eventual right heart failure. Classified as group IV within the WHO PH classification system, CTEPH is best treated with surgical pulmonary vessel endarterectomy [11]. However, many patients are unable to be treated surgically either owing to the location of lesions or comorbidities that preclude surgical treatment. Therefore, pharmacologic treatments are currently studied for the treatment of patients who cannot be helped surgically [12]. Treatments for PAH and CTEPH at various stages of investigation include inhaled NO, imatinib and newer analogs, Rho-kinase inhibitors and soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) stimulators/activators [13].

Current treatments of PH

Phosphodiesterase type-5 inhibitors increase intracellular levels of cGMP through inhibition of the phosphodiesterase enzyme responsible for cGMP degradation. Increases in cGMP concentrations leads to a decrease in intracellular calcium available for interaction with calmodulin in the initiation of smooth muscle contraction. The process increases smooth muscle relaxation in constricted vessels and promotes vasodilation. The pathway involving NO and cGMP also has important effects on inhibition of platelet aggregation and vascular smooth muscle proliferation. PDE-5 inhibitors, therefore, have been shown to have antiproliferative effects, counteracting the vascular remodeling process [14]. The three PDE-5 inhibitors approved for the treatment of erectile dysfunction, sildenafil, vardenafil and tadalafil, have beneficial pulmonary vasodilatory effects. The Sildenafil Use in Pulmonary Hypertension (SUPER) trial demonstrated symptomatic and functional improvement in PAH patients receiving sildenafil [15]. Tadalafil has been shown to have similar beneficial effects in a randomized controlled trial [16]. The effectiveness of these agents is based upon sufficient NO release from the endothelium to allow adequate levels of cGMP to be reached.

Prostacyclin is a potent vasodilator with inhibitory effects on platelet aggregation and vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation [5–8]. The studies of Kadowitz et al. [5] and Hyman and Kadowitz [6] were the first to demonstrate that prostacyclin had pulmonary vasodilator activity and suggested their benefit in the treatment of PH [5,6]. Synthetic prostacyclins include epoprostenol, iloprost, treprostinil and beraprost. Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated symptomatic, hemodynamic and exercise capacity improvements in patients treated with continuous intravenous infusion of epoprostenol, and intravenous or subcutaneous injection of iloprost and treprostinil [17–21]. Oral beraprost is currently being examined as another prostacyclin therapy for PAH. It has produced improvements in exercise capacity but not in symptoms or hemodynamics [22].

Endothelin-1, which is produced by the vascular endothelium, is responsible for induction of vasoconstriction and mitogenic activation of smooth muscle cell proliferation in PAH [23]. The endothelin antagonists bosentan, sitaxentan and ambrisentan have all been shown to improve hemodynamics and exercise tolerance in patients with PAH. Bosentan and ambrisentan both additionally improved exercise tolerance and time to clinical worsening in randomized clinical trials [24–29]. Endothelin antagonists and PDE-5 inhibitors are among the few classes of agents that have efficacy upon oral administration for PAH. However, liver toxicity is a significant side effect of endothelin antagonists.

For CTEPH patients who are not candidates for pulmonary arterial endarterectomy surgical intervention, clinical trials may offer the only means of clinical improvement. All CTEPH patients receive anticoagulation therapy prior to an intervention. Current trials have examined the use of the PH drug classes of prostanoids, PDE-5 inhibitors, and endothelin receptor antagonists for the treatment of CTEPH. These drugs were believed to be effective against CTEPH because the small vessel remodeling seen in PAH is histologically identical to the vasculopathy of CTEPH. Currently, these treatments have shown improvement in PVR but no increase in survival [30–33].

A diverse range of trials are ongoing for the treatment of PAH and CTEPH, examining molecules which improve endothelial function, enhance the NO signaling cascade or inhibit pulmonary vascular smooth muscle proliferation. We will now review animal and human trials within an exciting area of targeted therapy aimed at stimulating or activating sGC.

Soluble guanylate cyclase

Soluble guanylate cyclase is an intracellular signal-transducing enzyme composed of an α- and a β-subunit. The bioactivation of sGC is largely dependent on an interaction between NO and a reduced heme moiety within the β-subunit. NO binds the reduced heme, initiating cleavage of the ferrous iron (Fe2+) from a histidine residue and a change in the conformation of sGC to its active form. It has also been demonstrated that protoporphyrin IX can serve as a partial agonist of sGC in an NO-independent manner [34,35]. The activated heterodimeric enzyme’s involvement with inhibition of platelet aggregation and relaxation of smooth muscle in vascular beds has been well established for some time [36]. Activated sGC converts GTP to the intracellular second messenger cGMP. Increasing cGMP concentrations can affect multiple pathways, including activation of protein kinase G [37]. Protein kinase G activation leads to a decrease in cytosolic calcium, inhibition of the actin–myosin contractile system and vascular smooth muscle relaxation [2].

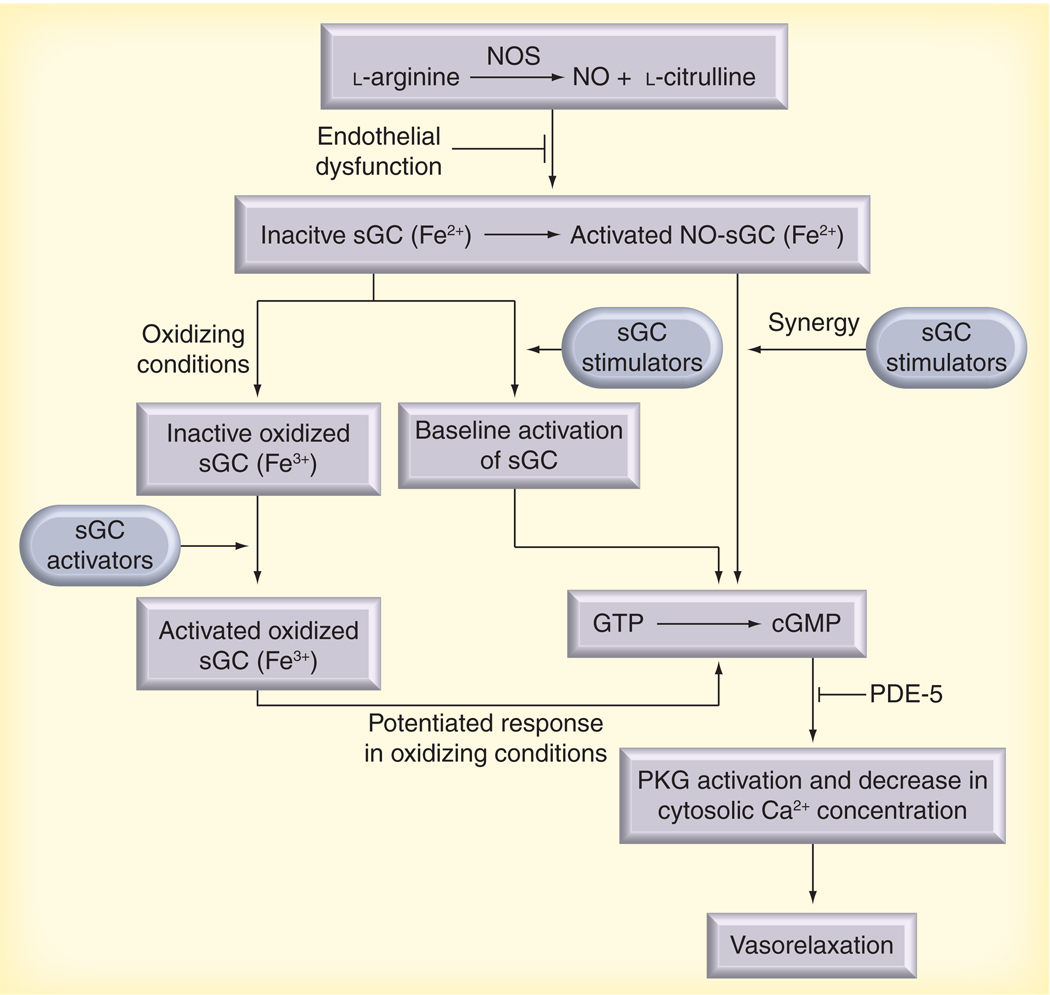

Alveolar ventilation and perfusion are largely dependent on a functioning NO–sGC–cGMP pathway within the vascular endothelium and smooth muscle of a healthy lung. The bioavailability of endogenous vasodilators, such as NO and prostacyclin, is significantly decreased in PAH [38]. Biochemical studies have shown that NO is incapable of activating oxidized (Fe3+) or heme-free sGC and provided evidence that oxidative stress may alter sGC bioactivity [39,40]. Interestingly, an increase in sGC expression was reported in experimental models of chronic hypoxia-induced PAH in the mouse, monocrotaline (MCT)-induced PAH in the rat, and in pulmonary arterial tissue samples obtained from patients with idiopathic PAH [2]. The prevalence of endothelial dysfunction in PH and the need for agents that act on the pulmonary vasculature in an NO-independent manner has led to the development and characterization of pharmacotherapies targeting sGC for the treatment of PH (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Endothelial release of nitric oxide is the initial step in vascular smooth muscle relaxation.

NOS is responsible for conversion of l-arginine to l-citrulline and the vasoactive NO. NO released from the endothelium interacts with the β-subunit of sGC, initiating a cleavage of a reduced heme moiety from a histidine residue and bioactivation of the enzyme. Activated sGC converts GTP to the intracellular second messenger cGMP within smooth muscle. Increasing cGMP concentrations results in decrease in intracellular calcium and subsequent smooth muscle relaxation. PDE-5 is the enzyme responsible for the breakdown of cGMP. Endothelial dysfunction and decreased levels of NOS are hallmarks of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). In these conditions, adequate levels of NO are not released from the pulmonary vascular endothelium, resulting in prolonged vasoconstriction of the pulmonary vascular beds. Heme-dependent sGC stimulators (YC-1, BAY 41–2272, BAY 41–8543 and BAY 63–2521) are capable of stimulating basal activity of reduced sGC enzyme independently of NO; however, these compounds also demonstrate a pronounced synergy upon sGC activity with any available NO. This characteristic makes these compounds attractive for treatment of PAH in conditions of endothelial dysfunction in which NO bioavailability may be markedly impaired. In addition to the heme-dependent, NO-independent stimulators, new sGC activators (BAY 58–2667, BAY 60–2770 and HMR 1766/S3448) have recently been described that demonstrate heme- and NO-independent bioactivity. These agents demonstrate baseline activation of sGC and additive effects with NO; however, substantially increased bioactivity is reported upon oxidized/heme-free sGC that was previously considered inert and is associated with inflammatory disease states in PAH.

NO: Nitric oxide; NOS: Nitric oxide synthase; PDE-5: Phosphodiesterase-5; PKG: Protein kinase G; sGC: Soluble guanylate cyclase.

sGC-stimulating compounds

In 1994, Ko et al. reported on a benzylindazole compound, YC-1 (3-[5’-hydroxymethyl-2’-furyl]-1-benzylindazole), that prolonged the tail bleeding time of conscious mice, demonstrated direct guanylate cyclase activation in rabbit platelets, and increased cGMP levels independent of NO [41]. This sGC-stimulating compound has multiple antithrombotic effects upon platelets, including activation of vasodilator- stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP), inhibition of aggregation and interference with collagen binding [42,43]. YC-1 has nonselective vasodilator activity and synergizes with NO to increase vasodilator responses to NO donors [44]. The compound’s pharmacologic effects have been shown to act in a NO-independent and heme-dependent manner. It has also been reported that YC-1 has NO-independent, heme-independent activity [45]. In vitro experiments have shown that YC-1 has an antiproliferative and anti-apoptotic effect upon vascular smooth muscle cells of the rat [40,43,46]. The mechanism of action for YC-1-mediated vasodilation has not been completely elucidated; however, it has been proposed that NO–YC-1 synergy exists because the stimulator maintains the active conformation of sGC through stabilization of the nitrosyl–heme complex [47,48]. Research with YC-1 has provided a basis for the development of sGC stimulators with improved potency and specificity, including BAY 41–2272, BAY 41–8543 and BAY 63–2521 [49,50].

Initial experiments with the pyrazolopyridine BAY 41–2272 demonstrated a 20-fold increase in sGC bioactivity in the absence of NO and the response was potentiated further with the addition of the NO donor diethylamine/nitric oxide [51]. When purified sGC was treated with a heme-removal detergent, it was reported that BAY 41–2272 had no activity on a heme-free sGC enzyme [51]. Conversely, it was later demonstrated that when 1H-(1,2,4)oxadiazolo-(4,3-a)quinoxalin-1-one (ODQ) was used to oxidize sGC, the relaxation capabilities of BAY 41–2272 remained intact [52]. Calcium channel blockade was hypothesized as an additional underlying mechanism of action for the sGC stimulator [52,53]. BAY 41–2272 partially reversed the pathologic structural alterations of the right heart and lung vasculature associated with PAH in experimental mouse and rat models [43]. Experiments have also shown that BAY 41–2272 and BAY 41–8543 both possess antiplatelet activity and inhibit smooth muscle cell proliferation [50,54].

It has been shown that administration of large doses of BAY 41–2272 result in nonselective vasodilation in an ovine model [55]. In the same study, coadministration of the NOS inhibitor N-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) blocked systemic vasodilation, but did not significantly alter pulmonary vasodilator activity [55]. Similarly, it was reported that when BAY 41–2272 or BAY 41–8543 were administered by inhalation to conscious lambs, the compounds had selective pulmonary activity and enhanced vasodilator responses to inhaled NO [56,57]. Recent studies have shown that the vasodilator activity of BAY 41–8543 is enhanced by coadministration of an NO donor and greatly diminished in both the systemic and pulmonary vascular beds of the intact chest rat when endogenous NO production is inhibited with L-NAME [58]. These results differ in regard to the role of endogenous NO in mediating the pulmonary vasodilator response when compared with studies in the ovine model. The reason for the difference in results may involve species variation, experimental design, route of administration or the mechanism of sGC stimulation in different model systems [58].

Clinical trials with riociguat (BAY 63–2521)

BAY 41–2272 and BAY 41–8543 have both been shown to have beneficial effects in the treatment of experimental PAH, however, the pharmacokinetic profiles suggest further refinement is needed in the development of a compound for clinical use [59]. Similar to BAY 41–2272 and BAY 41–8543, riociguat (BAY 63–2521) is a NO-independent, heme-dependent sGC stimulator that is capable of synergizing with NO over a wide range of concentrations [59]. The agent has been shown to partially reverse pulmonary vascular remodeling in two experimental models of PAH and had no effect on PDEs or other cyclic nucleotide metabolizing enzymes [2]. Clinical trials have begun to determine if sGC stimulators offer long-term benefit in patients with chronic PH.

Phase I studies were performed to determine the safety profile, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of riociguat in 58 healthy, male subjects given single oral doses in solution or an immediate-release tablet formulation [60]. Both forms of the agent were well tolerated, with mild side effects including headache, flushing and orthostatic hypotension with administration of the 5-mg dose. There was large variation in plasma concentrations of riociguat in different individuals given similar doses, suggesting the importance for titration of this agent in a clinical setting [60].

The initial Phase I study was followed by a proof-of-concept study to assess the effects of riociguat in 19 patients diagnosed with PAH [61]. Results from this study showed that riociguat had greater potency and duration of action than inhaled NO in patients with PAH. No significant side effects were observed other than mild dizziness, nasal congestion and flushing. The 1.0- and 2.5-mg doses of riociguat used in this study decreased PVR, mean PAP and improved cardiac index in a concentration-dependent manner [61]. Although systemic arterial pressure did not fall below 110 mmHg, the compound did cause systemic vasodilation. These results placed emphasis on the need for titration of doses to control for systemic effects if this compound is to be used clinically [62].

A 12-week, multi-institutional, Phase II trial of riociguat for treatment of CTEPH and PAH in 75 patients was recently completed in Germany [63]. Patients received oral riociguat 1.0–2.5 mg three-times daily, titrated to an effective dose for each patient according to systolic blood pressure measurements and hemodynamic improvement. Because riociguat caused both pulmonary and systemic vasodilation in this trial, the authors noted that in future patients individual dose adjustments would be necessary to control systemic effects. Results from this study indicated that riociguat was well tolerated with no clinically significant effect on vital signs, ECGs, routine laboratory values, gas exchange or ventilation–perfusion matching. Riociguat produced clinically significant improvement in PVR, mean PAP and cardiac index in patients with CTEPH as well as patients with PAH. Both PAH and CTEPH patient groups also had significant improvement in 6-min walk distance (6MWD) following riociguat treatment. Therefore, worldwide Phase III clinical studies have now been initiated for the use of riociguat in patients with CTEPH or PAH [101].

sGC-activating compounds

In addition to heme-dependent stimulators, an NO-independent class of sGC activators (BAY 58–2667, BAY 60–2770 and HMR 1766/S3448) has been introduced that targets an oxidized or heme-free form of sGC [39,64]. Contrary to the reported pharmacologic synergy recorded between sGC stimulators and NO, the amino dicarboxylic acid cinaciguat (BAY 58–2667) showed potent baseline stimulation and only additive effects with NO donors on purified sGC activity [64,65]. It was shown that a significant increase in cinaciguat bioactivity occurs with oxidation of sGC by ODQ or removal of the heme complex from the enzyme [64,66]. Cinaciguat has been reported to target the heme pocket of sGC and alter the enzyme to resemble the NO-active form [67]. The sGC activator causes significant pulmonary vasodilation and partially reverses PAH in chronically hypoxic mice and MCT-treated rats [68]. It has also recently been shown that cinaciguat improves cardiopulmonary hemodynamics in patients with acute decompensated heart failure, however, the activator has not been used in clinical trials for primary PAH [69].

Ataciguat (HMR-1766) is an anthranilic acid derivative that is structurally unrelated to cinaciguat, but also preferentially activates oxidized/heme-free sGC [65,70]. Ataciguat was shown to improve gas exchange, and cardiac output while maintaining systemic arterial pressure and attenuating right heart hypertrophy in MCT-induced PAH in the rat [71]. A recent study utilizing a continuous telemetric technique reported that subcutaneous injections of ataciguat significantly reduced right ventricular systolic pressure without decreasing systemic arterial pressure in a chronically hypoxic mouse model of PAH [72].

BAY 60–2770 is another agent that activates the reduced form of sGC as well as the oxidized or heme-deficient form of the enzyme. Results from recent experiments provide evidence that BAY 60–2770 has significant pulmonary and systemic vasodilatory activity in the intact-chest rat model that are markedly enhanced when NOS is inhibited or sGC is oxidized [73]. Additional experiments with animals infused with the TXA2 agonist, U-46619, also suggest that BAY 60–2770 may demonstrate selective pulmonary vasodilator activity when TXA2 levels are increased [73]. The capability of sGC activators to target oxidized and heme deficient enzyme seems to be ideal for treating PAH in patients with inflammatory disease states.

Investigative limitations

Patients with PAH exhibit classic histopathologic features of neointimal proliferation and plexiform lesions. Therefore, an accurate model of PAH should recapitulate these pathological findings. However, current rodent models of chronic hypoxia-induced and MCT-induced PAH are not the most robust representations of these features. Formation of neointimal lesions involving endothelial and smooth muscle-like cells has been reported in rats that underwent pneumonectomy in addition to MCT treatment [74]. This model suggests a ‘multiple-hit’ etiology of neointimal lesions in which increased blood flow to one lung (pneumonectomy) is combined with endothelial dysfunction (MCT treatment) to generate characteristic lesions. Future therapies must target both vascular remodeling in the diseased lung and the endothelial dysfunction seen in PH. Progressive and irreversible PH along with increased pulmonary vascular smoooth muscle cell proliferation has been reported in rats treated with VEGF receptor inhibitor Sugen 5416 (SU-5416) and subjected to chronic hypoxia [75]. Although certain limitations exist (e.g., neointimal proliferation is present while few plexiform lesions are observed in the MCT plus pneumonectomy model), these newer experimental methods may offer a more appropriate pathologic model for PAH and could be useful in improving our understanding of the therapeutic use of sGC stimulators/activators.

Combination therapy

Despite the development of new treatment options for PAH in recent years, the use of monotherapy targeting one of the primary etiologic pathways (i.e., endothelin-1, prostacyclin and NO) continues to result in clinical worsening over time or an inability to stabilize their condition in most patients [76]. In response to less than ideal outcomes, use of combination therapies has become common practice. The American College of Chest Physicians and American College of Cardiology Expert Consensus on PH do not support or disapprove of combination pharmacotherapy for PAH [77]. It has been recommended by the European Society of Cardiology and European Respiratory Society that combination therapy should be used in patients who show continued decline in measured parameters of 6MWD and lung function after monotherapy [10].

A thorough review of the pharmacology and pharmacokinetic considerations of combination therapy for PAH has been recently conducted [78]. In general, combination therapy has the benefit of potential lessening of side effects owing to elevated drug concentrations when high doses of a single agent are used [79]. Multidrug therapy targeting several pathways has proven successful in other disease states such as HIV, hypertension, heart failure and several malignancies. Furthermore, since delay of treatment initiation may lead to diminished therapeutic response, and further evidence that early use of combination therapy leads to enhanced results, the use of combination therapy as an initial treatment option should be considered [80].

Recently, Keogh et al. published the results of a survival study in which 112 patients were placed on combination therapy including bosentan, sitaxentan, ambrisentan, iloprost and sildenafil. The use of combination therapy improved 1-, 2- and 3-year survival rates, functional capacity, 6MWD, PAPs and right ventricular function [81]. Several studies have looked at the use of combination therapy in PH and these results have been recently reviewed [76,79]. Combination treatment with prostanoids and PDE-5 inhibitors, endothelin receptor antagonists and PDE-5 inhibitors, and prostanoids and endothelin receptor antagonists have been evaluated. These investigations involve small numbers of patients, limited improvement in outcome measures, and varying baseline WHO functional levels. Despite the accepted use of combination therapy in monotherapy-resistant PAH patients, more investigations are needed to assess side effects, clinically relevant end points and effective stratification across all WHO classes. Combination therapy is a powerful tool in the clinicians’ arsenal for treatment of PAH, however, more aggressive large-scale investigation is necessary before combination therapy is recommended as a first-line treatment. sGC activators and stimulators may have a role in combination therapy and further research into this area should be undertaken as our understanding of the use of these agents develops.

Expert commentary

Pulmonary hypertension is a fatal disease with few treatment options. Although much remains to be learned about the clinical utility of sGC stimulators and activators, there is reason for significant interest in the development of these new pharmacotherapies. The therapeutic synergy that exists between sGC stimulators and NO, as well as the potentiated effects of sGC activators upon oxidized/heme-deficient sGC, suggest the great potential of these agents. The results of experimental studies in animal models have improved our current knowledge about pathologic mechanisms of PH and new therapies have been developed that are being used in clinical trials. These advances are of major significance in moving to better clinical outcomes for patients with PH.

Five-year view

Impaired endothelial function changes the activity of intracellular pathways in PAH and may have a genetic basis. It is possible that gene or cell based therapies may be useful to correct impaired pathway function. Specific therapies, such as sGC stimulators/activators or Rho-kinase inhibitors, are being developed to selectively target the pulmonary vasculature and have little effect on the systemic circulation. Further research is needed in the next 5 years to develop new genetic, cell-based and pharmacologic therapies for clinical use.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

• of interest

•• of considerable interest

- 1.Archer SL, Weir EK, Wilkins MR. Basic science of pulmonary arterial hypertension for clinicians: new concepts and experimental therapies. Circulation. 2010;121(18):2045–2066. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.847707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schermuly RT, Stasch JP, Pullamsetti SS, et al. Expression and function of soluble guanylate cyclase in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2008;32(4):881–891. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00114407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Alonzo GE, Barst RJ, Ayres SM, et al. Survival in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Results from a national prospective registry. Ann. Intern. Med. 1991;115(5):343–349. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-5-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giaid A, Saleh D. Reduced expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in the lungs of patients with pulmonary hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;333(4):214–221. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199507273330403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kadowitz PJ, Chapnick BM, Feigen LP, Hyman AL, Nelson PK, Spannhake EW. Pulmonary and systemic vasodilator effects of the newly discovered prostaglandin, PGI2. J. Appl. Physiol. 1978;45(3):408–413. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1978.45.3.408. • One of the first studies to demonstrate pulmonary vasodilator activity of prostacyclins.

- 6.Hyman AL, Kadowitz PJ. Pulmonary vasodilator activity of prostacyclin (PGI2) in the cat. Circ. Res. 1979;45(3):404–409. doi: 10.1161/01.res.45.3.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones DA, Benjamin CW, Linseman DA. Activation of thromboxane and prostacyclin receptors elicits opposing effects on vascular smooth muscle cell growth and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling cascades. Mol. Pharmacol. 1995;48(5):890–896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galie N, Manes A, Branzi A. Prostanoids for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Med. 2003;2(2):123–137. doi: 10.1007/BF03256644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christman BW, McPherson CD, Newman JH, et al. An imbalance between the excretion of thromboxane and prostacyclin metabolites in pulmonary hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med. 1992;327(2):70–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199207093270202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galie N, Hoeper MM, Humbert M, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS), endorsed by the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) Eur. Heart J. 2009;30(20):2493–2537. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simonneau G, Galie N, Rubin LJ, et al. Clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2004;43 Suppl. 12:5S–12S. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jamieson SW, Kapelanski DP, Sakakibara N, et al. Pulmonary endarterectomy: experience and lessons learned in 1,500 cases. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2003;76(5):1457–1462. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(03)00828-2. discussion 1462–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stenmark KR, Rabinovitch M. Emerging therapies for the treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2010;11 Suppl. 2:S85–S90. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181c76db3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wharton J, Strange JW, Moller GM, et al. Antiproliferative effects of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibition in human pulmonary artery cells. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2005;172(1):105–113. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200411-1587OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Galie N, Ghofrani HA, Torbicki A, et al. Sildenafil citrate therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;353(20):2148–2157. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050010. • Report on phosphodiesterase type-5 inhibitor use and efficacy for the treatment of pulmonary hypertension.

- 16.Galie N, Brundage BH, Ghofrani HA, et al. Tadalafil therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation. 2009;119(22):2894–2903. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.839274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubin LJ, Mendoza J, Hood M, et al. Treatment of primary pulmonary hypertension with continuous intravenous prostacyclin (epoprostenol). Results of a randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 1990;112(7):485–491. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-112-7-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Barst RJ, Rubin LJ, Long WA, et al. A comparison of continuous intravenous epoprostenol (prostacyclin) with conventional therapy for primary pulmonary hypertension. The Primary Pulmonary Hypertension Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996;334(5):296–302. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602013340504. • Report on prostacyclin use and efficacy for the treatment of pulmonary hypertension.

- 19.Higenbottam T, Butt AY, McMahon A, Westerbeck R, Sharples L. Long-term intravenous prostaglandin (epoprostenol or iloprost) for treatment of severe pulmonary hypertension. Heart. 1998;80(2):151–155. doi: 10.1136/hrt.80.2.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simonneau G, Barst RJ, Galie N, et al. Continuous subcutaneous infusion of treprostinil, a prostacyclin analogue, in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002;165(6):800–804. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.6.2106079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barst RJ, Galie N, Naeije R, et al. Long-term outcome in pulmonary arterial hypertension patients treated with subcutaneous treprostinil. Eur. Respir. J. 2006;28(6):1195–1203. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00044406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galie N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, et al. Effects of beraprost sodium, an oral prostacyclin analogue, in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2002;39(9):1496–1502. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01786-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giaid A, Yanagisawa M, Langleben D, et al. Expression of endothelin-1 in the lungs of patients with pulmonary hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993;328(24):1732–1739. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199306173282402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Channick RN, Simonneau G, Sitbon O, et al. Effects of the dual endothelin-receptor antagonist bosentan in patients with pulmonary hypertension: a randomised placebo-controlled study. Lancet. 2001;358(9288):1119–1123. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06250-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rubin LJ, Badesch DB, Barst RJ, et al. Bosentan therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002;346(12):896–903. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galie N, Badesch D, Oudiz R, et al. Ambrisentan therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2005;46(3):529–535. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barst RJ, Langleben D, Badesch D, et al. Treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension with the selective endothelin-A receptor antagonist sitaxsentan. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006;47(10):2049–2056. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benza RL, Barst RJ, Galie N, et al. Sitaxsentan for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension: a 1-year, prospective, open-label observation of outcome and survival. Chest. 2008;134(4):775–782. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galie N, Olschewski H, Oudiz RJ, et al. Ambrisentan for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension: results of the ambrisentan in pulmonary arterial hypertension, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter, efficacy (ARIES) study 1 and 2. Circulation. 2008;117(23):3010–3019. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.742510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghofrani HA, Schermuly RT, Rose F, et al. Sildenafil for long-term treatment of nonoperable chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2003;167(8):1139–1141. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200210-1157BC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bresser P, Fedullo PF, Auger WR, et al. Continuous intravenous epoprostenol for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2004;23(4):595–600. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00020004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoeper MM, Kramm T, Wilkens H, et al. Bosentan therapy for inoperable chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Chest. 2005;128(4):2363–2367. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jais X, D’Armini AM, Jansa P, et al. Bosentan for treatment of inoperable chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: BENEFiT (bosentan effects in inoperable forms of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension), a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008;52(25):2127–2134. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Murad F, Mittal CK, Arnold WP, Katsuki S, Kimura H. Guanylate cyclase: activation by azide, nitro compounds, nitric oxide, and hydroxyl radical and inhibition by hemoglobin and myoglobin. Adv. Cyclic. Nucleotide Res. 1978;9:145–158. • One of the first studies to demonstrate activation of soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) by nitric oxide (NO).

- 35.Ignarro LJ, Wood KS, Wolin MS. Activation of purified soluble guanylate cyclase by protoporphyrin IX. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1982;79(9):2870–2873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.9.2870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ignarro LJ, Kadowitz PJ. The pharmacological and physiological role of cyclic GMP in vascular smooth muscle relaxation. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1985;25:171–191. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.25.040185.001131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lucas KA, Pitari GM, Kazerounian S, et al. Guanylyl cyclases and signaling by cyclic GMP. Pharmacol. Rev. 2000;52(3):375–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McLaughlin VV, McGoon MD. Pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation. 2006;114(13):1417–1431. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.503540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stasch JP, Schmidt PM, Nedvetsky PI, et al. Targeting the heme-oxidized nitric oxide receptor for selective vasodilatation of diseased blood vessels. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116(9):2552–2561. doi: 10.1172/JCI28371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stasch JP, Hobbs AJ. NO-independent, haem-dependent soluble guanylate cyclase stimulators. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2009;(191):277–308. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-68964-5_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ko FN, Wu CC, Kuo SC, Lee FY, Teng CM. YC-1, a novel activator of platelet guanylate cyclase. Blood. 1994;84(12):4226–4233. • First paper to demonstrate the NO-independent, sGC-stimulating capabilities of the YC-1 compound.

- 42.Becker EM, Schmidt P, Schramm M, et al. The vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP): target of YC-1 and nitric oxide effects in human and rat platelets. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2000;35(3):390–397. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200003000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tulis DA, Bohl Masters KS, Lipke EA, et al. YC-1-mediated vascular protection through inhibition of smooth muscle cell proliferation and platelet function. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;291(4):1014–1021. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mulsch A, Bauersachs J, Schafer A, Stasch JP, Kast R, Busse R. Effect of YC-1, an NO-independent, superoxide-sensitive stimulator of soluble guanylyl cyclase, on smooth muscle responsiveness to nitrovasodilators. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;120(4):681–689. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0700982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martin E, Lee YC, Murad F. YC-1 activation of human soluble guanylyl cyclase has both heme-dependent and heme-independent components. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98(23):12938–12942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231486198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pan SL, Guh JH, Chang YL, Kuo SC, Lee FY, Teng CM. YC-1 prevents sodium nitroprusside-mediated apoptosis in vascular smooth muscle cells. Cardiovasc. Res. 2004;61(1):152–158. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Friebe A, Koesling D. Mechanism of YC-1-induced activation of soluble guanylyl cyclase. Mol. Pharmacol. 1998;53(1):123–127. doi: 10.1124/mol.53.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Russwurm M, Mergia E, Mullershausen F, Koesling D. Inhibition of deactivation of NO-sensitive guanylyl cyclase accounts for the sensitizing effect of YC-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277(28):24883–24888. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110570200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Selwood DL, Brummell DG, Budworth J, et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of novel pyrazoles and indazoles as activators of the nitric oxide receptor, soluble guanylate cyclase. J. Med. Chem. 2001;44(1):78–93. doi: 10.1021/jm001034k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stasch JP, Alonso-Alija C, Apeler H, et al. Pharmacological actions of a novel NO-independent guanylyl cyclase stimulator, BAY 41–8543: in vitro studies. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;135(2):333–343. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stasch JP, Becker EM, Alonso-Alija C, et al. NO-independent regulatory site on soluble guanylate cyclase. Nature. 2001;410(6825):212–215. doi: 10.1038/35065611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Priviero FB, Baracat JS, Teixeira CE, Claudino MA, De Nucci G, Antunes E. Mechanisms underlying relaxation of rabbit aorta by BAY 41–2272, a nitric oxide-independent soluble guanylate cyclase activator. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2005;32(9):728–734. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2005.04262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Priviero FB, Webb RC. Heme-dependent and independent soluble guanylate cyclase activators and vasodilation. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2010;56(3):229–233. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181eb4e75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hobbs AJ, Moncada S. Antiplatelet properties of a novel, non-NO-based soluble guanylate cyclase activator, BAY 41–2272. Vascul. Pharmacol. 2003;40(3):149–154. doi: 10.1016/s1537-1891(03)00046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Evgenov OV, Ichinose F, Evgenov NV, et al. Soluble guanylate cyclase activator reverses acute pulmonary hypertension and augments the pulmonary vasodilator response to inhaled nitric oxide in awake lambs. Circulation. 2004;110(15):2253–2259. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000144469.01521.8A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Deruelle P, Grover TR, Abman SH. Pulmonary vascular effects of nitric oxide-cGMP augmentation in a model of chronic pulmonary hypertension in fetal and neonatal sheep. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2005;289(5):L798–L806. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00119.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Evgenov OV, Kohane DS, Bloch KD, et al. Inhaled agonists of soluble guanylate cyclase induce selective pulmonary vasodilation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2007;176(11):1138–1145. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200707-1121OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Badejo AM, Jr, Nossaman VE, Pankey EA, et al. Pulmonary and systemic vasodilator responses to the soluble guanylyl cyclase stimulator, BAY 41–8543, are modulated by nitric oxide. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2010;299(4):H1153–H1159. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01101.2009. • Paper suggests significant role of endogenous NO-mediated induction present in systemic and pulmonary vasodilatory responses in the rat.

- 59.Mittendorf J, Weigand S, Alonso-Alija C, et al. Discovery of riociguat (BAY 63–2521): a potent, oral stimulator of soluble guanylate cyclase for the treatment of pulmonary hypertension. ChemMedChem. 2009;4(5):853–865. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200900014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Frey R, Muck W, Unger S, Artmeier-Brandt U, Weimann G, Wensing G. Single-dose pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, tolerability, and safety of the soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator BAY 63–2521: an ascending-dose study in healthy male volunteers. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008;48(8):926–934. doi: 10.1177/0091270008319793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Grimminger F, Weimann G, Frey R, et al. First acute haemodynamic study of soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator riociguat in pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2009;33(4):785–792. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00039808. • • First clinical trial reporting efficacy of sGC-stimulating compund riociguat in patients with pulmonary hypertension.

- 62.Ghofrani H, Grimminger F. Soluble guanylate cyclase stimulation: an emerging option in pulmonary hypertension therapy. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2009;18(111):35–41. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00011112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ghofrani HA, Hoeper MM, Halank M, et al. Riociguat for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary arterial hypertension: a Phase II study. Eur. Respir. J. 2010;36(4):792–799. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00182909. • • Phase II clinical trial evaluating the use of riociguat in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension.

- 64.Stasch JP, Schmidt P, Alonso-Alija C, et al. NO- and haem-independent activation of soluble guanylyl cyclase: molecular basis and cardiovascular implications of a new pharmacological principle. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;136(5):773–783. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schindler U, Strobel H, Schonafinger K, et al. Biochemistry and pharmacology of novel anthranilic acid derivatives activating heme-oxidized soluble guanylyl cyclase. Mol. Pharmacol. 2006;69(4):1260–1268. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.018747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schmidt P, Schramm M, Schroder H, Stasch JP. Mechanisms of nitric oxide independent activation of soluble guanylyl cyclase. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2003;468(3):167–174. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01674-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schmidt HH, Schmidt PM, Stasch JP. NO- and haem-independent soluble guanylate cyclase activators. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2009;136(191):309–339. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-68964-5_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dumitrascu R, Weissmann N, Ghofrani HA, et al. Activation of soluble guanylate cyclase reverses experimental pulmonary hypertension and vascular remodeling. Circulation. 2006;113(2):286–295. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.581405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Lapp H, Mitrovic V, Franz N, et al. Cinaciguat (BAY 58–2667) improves cardiopulmonary hemodynamics in patients with acute decompensated heart failure. Circulation. 2009;119(21):2781–2788. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.800292. • Clinical study performed with sGC-activating compound reported improvements in patients with acute decompensated heart failure.

- 70.Zhou Z, Pyriochou A, Kotanidou A, et al. Soluble guanylyl cyclase activation by HMR-1766 (ataciguat) in cells exposed to oxidative stress. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2008;295(4):H1763–H1771. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.51.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schafer A, Bauersachs J. Therapeutic targets of ataciguat. Drugs Fut. 2007;32:731–738. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Weissmann N, Hackemack S, Dahal BK, et al. The soluble guanylate cyclase activator HMR1766 reverses hypoxia-induced experimental pulmonary hypertension in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2009;297(4):L658–L665. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00189.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pankey EA, Bhartija M, Badejo AM, et al. Pulmonary and systemic vasodilator responses to the soluble guanylyl cyclase activator, BAY 60–2770, are not dependent on endogenous nitric oxide or reduced heme. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2011;300(3):H792–H802. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00953.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Okada K, Tanaka Y, Bernstein M, Zhang W, Patterson GA, Botney MD. Pulmonary hemodynamics modify the rat pulmonary artery response to injury. A neointimal model of pulmonary hypertension. Am. J. Pathol. 1997;151(4):1019–1025. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Taraseviciene-Stewart L, Kasahara Y, Alger L, et al. Inhibition of the VEGF receptor 2 combined with chronic hypoxia causes cell death-dependent pulmonary endothelial cell proliferation and severe pulmonary hypertension. FASEB J. 2001;15(2):427–438. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0343com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Meis T, Behr J. Pulmonary hypertension: role of combination therapy. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2010 doi: 10.2174/157016111796197242. (In Press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.McLaughlin VV, Archer SL, Badesch DB, et al. ACCF/AHA 2009 expert consensus document on pulmonary hypertension: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents and the American Heart Association: developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, Inc., and the Pulmonary Hypertension Association. Circulation. 2009;119(16):2250–2294. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gokhman R, Smithburger PL, Kane-Gill SL, Seybert AL. Pharmacologic and pharmacokinetic rationale for combination therapy in pulmonary arterial hypertension. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2010;56(6):686–695. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181f89bdb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.O’Callaghan DS, Savale L, Jais X, et al. Evidence for the use of combination targeted therapeutic approaches for the management of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Respir. Med. 2010;104 Suppl. 1:S74–S80. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Affuso F, Cirillo P, Ruvolo A, Carlomagno G, Fazio S. Long term combination treatment for severe idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. World J. Cardiol. 2010;2(3):68–70. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v2.i3.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Keogh A, Strange G, Kotlyar E, et al. Survival after the initiation of combination therapy in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension – an Australian collaborative report. Intern. Med. J. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2010.02403.x. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Website

- 101.Now enrolling: Riociguat Phase III clinical trials. http://phaeurope.org/?Clinical_Trials:2007%2C_Get_together:Riociguat.