Abstract

Purpose

To study the role of survivin and its splice variants in taxane-resistant ovarian cancer.

Experimental Design

We assessed the messenger RNA levels of survivin splice variants in ovarian cancer cell lines and ovarian tumor samples. Small-interference RNAs (siRNAs) targeting survivin were designed to silence all survivin splice variants (T-siRNA) or survivin 2B (2B-siRNA) in vitro and orthotopic murine models of ovarian cancer. The mechanism of cell death was studied taxane-resistant ovarian cancer cells and in tumor sections obtained from different mouse tumors.

Results

Taxane-resistant ovarian cancer cells express higher survivin mRNA levels than their taxane-sensitive counterparts. Survivin 2B expression was significantly higher in taxane-resistant compared to sensitive cells. Silencing survivin 2B induced growth inhibitory effects similar to silencing total survivin in vitro. In addition, survivin 2B siRNA incorporated into DOPC nanoliposomes resulted in significant reduction in tumor growth (p<0.05) in orthotopic murine models of ovarian cancer, and these effects were similar to T-siRNA-DOPC. The anti-tumor effects were further enhanced in combination with docetaxel chemotherapy (p<0.01). Finally, we found a significant association between survivin 2B expression and progression free survival in 117 epithelial ovarian cancers obtained at primary debulking surgery.

Conclusions

These data identify survivin 2B as an important target in ovarian cancer, and provide a translational path forward for developing new therapies against this target.

Keywords: survivin, siRNA, nanoliposomes, ovarian cancer, taxanes

Introduction

Survivin [baculoviral IAP repeat-containing protein (BIRC-5)] belongs to the inhibitor of apoptosis protein (IAP) family (1, 2) characterized by one to three BIR (Baculoviral IAP repeats) domains, a COOH-terminal RING finger domain, and a caspase recruitment domain (2). However, in contrast with other IAPs, survivin lacks a RING finger domain (2). The mechanisms by which survivin, and other IAPs, exert their anti-apoptotic effect have been well characterized in vitro and in vivo (3–5). This mechanism involves formation of a complex between IAPs and effector caspases (2, 6) that result in inhibition of the apoptotic pathway (6). As a subunit of the chromosomal passenger complex (CPC), survivin also plays a critical role in the regulation of mitosis (7, 8).

Survivin has been amply considered an anticancer target because it is highly expressed in several types of cancer, but is largely undetectable in most normal adult tissues (1, 9). Evidence also indicates that survivin plays a central role in cancer drug resistance (10–13). In ovarian cancer, progressive taxane resistance in vitro is associated with increasing survivin expression (11). Likewise, higher levels of survivin have been observed in advanced ovarian carcinomas associated with clinical resistance to a paclitaxel/platinum chemotherapy compared with drug sensitive-cases (11).

Five different isoforms of survivin, arising from alternative splicing of the survivin (BIRC-5) gene, have been identified (14–17). These include the wild-type (WT) survivin, survivin 2B, survivin 3B, survivin ΔEx3 and survivin 2α (14, 15, 17, 18). Growing evidence indicates that the survivin splice variants could have different, even opposite, biological roles (16, 17, 19, 20). While some survivin splice variants could play an anti-apoptotic role, others could be associated with mitosis (14–16, 21, 22). The lack of information regarding the biological role of survivin splice variants in taxane-resistant ovarian cancer prompted us to consider their specific roles. Our data indicate that compared with taxane-sensitive counterparts, taxane-resistant ovarian cancer cells express higher mRNA levels of specific survivin splice variants, particularly survivin 2B. Here, we examined the In vitro and in vivo effects of silencing of survivin splice variants in pre-clinical models of ovarian cancer, and determined the clinical significance of survivin 2B mRNA expression levels in ovarian cancers.

Materials and Methods

Cells and culture conditions

The human ovarian epithelial cancer cells SKOV3ip1, SKOV3.TR, HeyA8, HEYA8.MDR, A2780PAR and A2780CP20 cells have been described elsewhere (23–26). All tumor cell lines were screened for Mycoplasma using MycoAlert (Cambrex Bioscience) as described by the manufacturer. Cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) in 5% CO2/95% air at 37°C. In vitro assays were performed at 70–85% cell density.

Chemicals, reagents and antibodies

For in vitro testing, docetaxel and paclitaxel were reconstituted in 100% DMSO. When added to the cells, the final concentration of DMSO on the culture medium was 0.1% or less. Monoclonal antibodies against caspase-8, caspase-3, caspase-9 and PARP-1, cdk2, p27 and cyclin E were purchased from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). Monoclonal anti-b-actin was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Mouse and rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Western blot analysis

Cells were washed with cold PBS, lysed with ice-cold lysis buffer and incubated on ice for 30 min. Lysates were centrifuged, supernatants were collected, and protein concentration was determined using Bio-Rad Protein Reagents (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Protein lysates (30 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE, blotted onto membranes, and probed with the appropriate dilution of each primary antibody. Membranes were rinsed and incubated with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody, rinsed again, and the bound antibodies were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) following by autoradiography in a FluorChemTM 8900 (Alpha Innotech Corporation, San Leandro, CA).

RNA isolation and SYBR-1-based real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cells using the Rneasy kit from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). Total RNA (1.0 μg) was subjected to reverse transcription in a reaction mix containing 500 mg/ml oligo dT, 1X First Strand Buffer, 0.01 M DTT, 0.5 mM dNTP mix, and 200 units of MMLV RT (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) to a final volume of 20 ml, and incubated at 40°C for 2 hr. The resulting first-strand cDNA was used as a template for SYBR-I-based real-time PCR analysis (27). Primers (Invitrogen): total survivin: forward: AGCCCTTTCTCAAGGACCAC, reverse: CAGCTCCTTGAAGCAGAAGAA; common forward primer for WT, 2B and ΔEX3 isoforms: GACCACCGCATCTCTACATTC; reverse: WT: TGCTTTTTATGTTCCTCTATGGG, 2B: AAGTGCTGGTATTACAGGCGT, ΔEx3: ATTGTTGGTTTCCTTTGCATG, 2α forward: GCTTTGTTTTGAACTGAGTTGTCAA, reverse: GCAATGAGGGTGGAAAGCA (21), 3B forward: GAGGCTGGCTTCATCCACTG, reverse: GCTCTCTCAATTTTGTTCTTG (18) AGCATTCGTCCGGTTGCGCT, β-actin forward: ATAGCACAGCCTGGATAGCAACGTAC, and reverse: CACCTTCTACAATGAGCTGCGTGTG. Two microliters of cDNA was added to QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems Carlsbad, CA) containing 200 nM of each primer. PCR was performed in a StepOne plus (Applied Biosystems) real-time PCR using the following thermal settings: one cycle of 15 min at 95°C, and 40 cycles of 15 s at 94°C, 30 s at X°C (X= 58°C for WT, 2B, and ΔEX3; 60°C for β-actin; 50°C for 2α and 54°C for 3B) and 30 s at 72°C. Relative mRNA expression was calculated with theΔΔCt-method (28, 29).

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) and in vitro siRNA transfection

To silence total human survivin (NM_001168), siRNA (5′-CAGACTTGGCCCAGTGTTT-3′) was designed in exon 2, which is common to all survivin splice variants. SiRNA duplex targeting the 5′-AATACCAGCACTTTGGGAG-3′ sequence in the open reading frame of the human survivin-2B (NM_001012271) and a non-silencing negative control siRNA (C-siRNA) was used. SiRNAs were purchased from Sigma. Briefly, 3×104 cells/ml were plated in 6-well plates. Twenty-four hours later, 3 μg of siRNA were mixed with HiPerFect transfection reagent (Qiagen) at 1:3 ratio (siRNA: transfection reagent). The mix was incubated 10 min at room temperature (RT) and then added to the cells. Cells were collected 48-hr later to assess the downregulation of each target.

In vitro cell viability assay

Cells (2×104 cells/ml) were plated in a 96-well plate. Twenty-four hours later, docetaxel or siRNAs were added to the cells and incubated for 72-hr. The medium was then removed and 100 μl of Alamar blue dye (Invitrogen) was added following the manufacturer’s instructions. OD values were obtained spectrophotometrically in a plate reader (Kinetic Microplate Reader; Molecular Devices Corp. Sunnyvale, CA) after 3-hr of dye incubation. To assess the effect of combining siRNA and docetaxel, cells were plated, and 24-hr later siRNA was added to cells and incubated for another 24-hr. Docetaxel was then added and cells were incubated for other 72-hr. In all cases, percentages of cell growth inhibition were obtained after blank OD subtraction, taking the untreated cells values as 0% of inhibition.

Assessment of cell apoptosis and cell cycle progression

Apoptosis was measured with the FITC-apoptosis detection kit (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), which uses Annexin-V and propidium iodide (PI) as the apoptotic and necrotic markers, respectively. Briefly, HEYA8.MDR cells (1×105) were collected, washed, and re-suspended in 1X binding buffer. Cells were incubated for 10 min with Annexin-V and/or propidium iodide according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After the addition of 500 μl of 1X binding buffer, apoptotic cells were analyzed in a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). CellQuestTM Pro software (BD Biosciences) was used to determine the number of apoptotic and necrotic cells. To assess cell cycle, cells were transfected with siRNAs and 48-hr later cells were collected and fixed with 70% cold ethanol and stored at −20°C. Twenty-four hours later, cells were collected and re-suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 50 mg/ml (final concentration) propidium iodide and 100 units/ml (final concentration) RNAse A. The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 30 min in the dark, and then analyzed by flow cytometry in a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). CellQuestTM Pro software (BD Biosciences) was used to determine the number of cells in each phase of the cell cycle.

SiRNA incorporation into DOPC nanoliposomes

For in vivo delivery, siRNAs were incorporated into 1,2-Dioleoyl-sn-Glycero-3-Phosphocholine (siRNA-DOPC) (Avanti Polar Lipids, INC, Alabaster, AL). SiRNA and DOPC were mixed in the presence of excess t-butanol at a ratio of 1:10 (w/w) as described previously (23, 24, 30–32). After Tween 20 was added, the mixture was frozen in an acetone-dry ice bath, and lyophilized. Before in vivo administration, the lyophilized powder was hydrated with Ca2+ and Mg2+ free PBS at a concentration of 25 mg/ml to achieve the desired dose in 200 μl/injection.

Orthotopic tumor implantation and drug treatment

Female athymic nude mice (NCr-nu, 8 to 12 weeks old.) were purchased from Taconic (Hudson, NY, USA). To generate tumors, HEYA8.MDR (5×105 cells/0.2 mL HBSS) and SKOV3.TR (1×106 cells/0.2 mL HBSS) were injected into the peritoneal cavity of nude mice. To assess the efficacy of each siRNA for silencing the target in vivo, nude mice bearing HEYA8.MDR tumors were randomly divided into 3 groups (N=3 per group): 1) non-silencing siRNA (C-siRNA), 2) total-survivin siRNA (T-siRNA), and 3) 2B-siRNA. One dose (5 μg siRNA/mouse) of each siRNA was administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) 3-weeks after tumor implantation. Two days after siRNA injection, animals were sacrificed; tumors were removed and stored at −80°C for total RNA isolation.

To evaluate the therapeutic activity of survivin siRNAs alone or in combination with docetaxel HeyA8.MDR were injected i.p. Seven days later, the mice (N=10 per group) were randomly assigned to seven treatment groups (all treatments were administered i.p.): 1) C-siRNA, 2) docetaxel (DTX) alone, 3) C- siRNA- plus DTX, 4) T-siRNA, 5) T-siRNA plus DTX, 6) 2B-siRNA, and 7) 2B-siRNA plus DTX. Liposomal-siRNAs (5 μg siRNA/injection) were injected twice a week and docetaxel (50 μg/injection) once a week (23, 24). The therapeutic experiment was repeated with SKOV3.TR cells.

Immunohistochemistry

Expression of Ki67 (cell proliferation marker) and Immunohistochemistry for CD31 (microvessel density) were done on paraffin-embedded tumors as described before (23, 24, 30). Ki67 primary antibody (BioCare Medical, Concord, CA) and secondary goat HRP anti-rabbit (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were used. The primary antibody used for CD31 was an anti-CD31 (platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1, rat IgG; BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). Secondary antibody was goat HRP anti-rat (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME). Assessment of deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL)-positive cells (apoptosis) were determined by immunohistochemical analysis using freshly cut frozen tissue as described previously (23, 24, 30, 31).

To quantify microvessel density (MVD), 10 random fields at 100x final magnification were examined for each tumor (one slide per mouse, five slides per group) and the number of microvessels per field was counted (23, 24, 26). To quantify Ki67 expression, the number of positive and negative cells (3,3′-diaminobenzidine staining) was counted in 10 random fields at 100x magnification and the percent of Ki67 positive cells was calculated for each group (23, 24, 26). To quantify TUNEL positive cells, the number of positive cells was counted in 10 random fields at 100x magnification (23, 24, 26).

RNA extraction from human epithelial ovarian cancer specimens

After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval, we obtained 117 human epithelial ovarian carcinoma specimens that were archived and freshly frozen at the time of primary debulking at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer. These samples (35 mg, each) were frozen in liquid nitrogen and homogenized with trizol (1 μL; Invitrogen) using mortar and pestle. Chloroform (200 μL) was added and samples were centrifuged at 12000 x g. Total RNA was precipitated with isopropanol (500 μL), washed with 75% ethanol, air-dried, and dissolved in RNase-free water. RNA quality and concentration was determined and RNA with > 1.5 OD ratio (260/280) was utilized to generate complementary DNA (cDNA) using superscript-II reverse transcriptase kit (Invitrogen) as previously described (27, 29). Kaplan-Meier survival curves were used to determine the association between the survivin 2B mRNA expression levels and survival endpoints (both progression-free (PFS) and overall survival (OS) times, both measured from the time of debulking surgery).

Statistical analysis

For in vivo experiments, differences in continuous variables (mean body weight, tumor weight, MVD, Ki-67 and TUNEL staining) were analyzed using the Student’s t test for comparing two groups and by ANOVA for multiple group comparisons with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant. To examine the interaction index (II) between T-siRNA, 2B-siRNA and docetaxel, an isobolanalysis was used as described by Feleszko et al (33). Briefly, equieffective concentrations (concentrations of either drug, alone, or in combination that gave equivalent inhibition of cell growth as compared with untreated control cells) were calculated. The interaction index for combination of the two drugs was calculated according to the following equation:

where siRNAa and DTXa are concentrations of T-siRNA, 2B-siRNA and docetaxel, respectively, that produce some specified effect when used alone, and siRNAc and c are concentrations of T-siRNA, 2B-siRNA and docetaxel, respectively, that produce the same effect when used in combination. The interaction is considered synergistic when the II is less than 1.0.

Results

Expression of survivin splice variants in ovarian cancer cells

We first performed growth inhibition experiments to confirm the responsiveness of the ovarian parental cancer cells lines HEYA8 and SKOV3ip1, and their taxane resistant counterparts, HEYA8.MDR and SKOV3i.TR, respectively (31–33) (Figure 1S). As expected, the resistant cells had no response while the sensitive cells had a dose-dependent response.

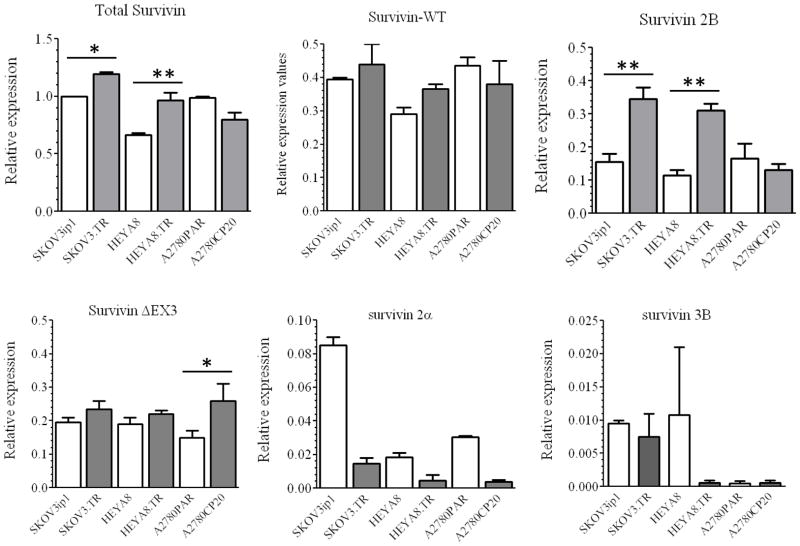

We next used SYBR-I-real time PCR to compare the mRNA expression levels of the five survivin splice variants in taxane-sensitive ovarian cancer cells and their taxane-resistant counterparts (Figure 1). Although survivin WT isoform was present in all cell lines studied, survivin 2B was approximately 3-fold more abundant in the taxane-resistant compared with the taxane-sensitive ovarian cancer cells. This pattern was not observed in the cisplatin-sensitive A2780PAR ovarian cancer cell and its cisplatin resistant counterpart, AP2780CP20. The mRNA expression levels of survivin 2α and survivin 3B were negligible as compared to other isoforms. Therefore, we focused on the survivin 2B isoform for all subsequent work.

Figure 1. Expression of survivin splice variants in ovarian cancer cells.

Total RNA was extracted from cells to doing SYBR-I-based real-time PCR as described in the “Materials and Methods” section. β-actin was used as the “endogenous control”. Messenger RNA expression levels were calculated with the ΔΔCt method. The relative mRNA expression level of each survivin splice variant was expressed relative to the total survivin of the SKOV3ip1 cell line, which was taken as 1.0. (*p<0.05, **p<0.01). Columns represent the means of triplicates ± S.D.

Effects of survivin 2B silencing on cell growth

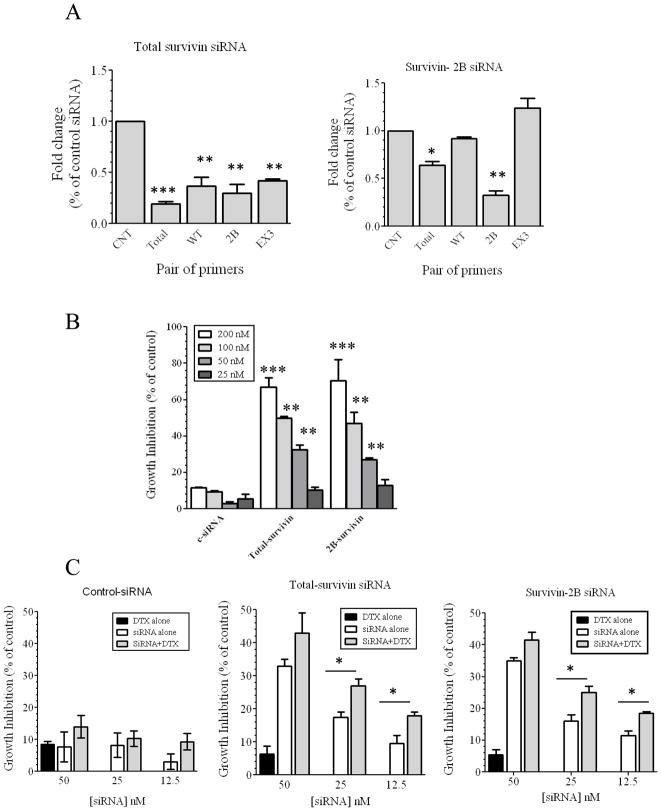

SiRNAs were designed around exon two (Figure 2S-A) to silence all splice variants (T-siRNA). Another set of siRNAs were designed to specifically silence survivin 2B (Figure 2S-A). We next studied the biological effects of siRNA-based silencing of survivin 2B (2B-siRNA) as compared to silencing total Survivin (Figure 2A). Real-time PCR experiments demonstrated that T-siRNA significantly reduced the levels of total survivin and the survivin splice variants WT, 2B and ΔEX3 in the HeyA8-MDR cell line. 2B-siRNA inhibited the expression of this isoform, but not survivin WT or ΔEX3, demonstrating that this siRNA was specific for survivin 2B. Maximal silencing of both survivin 2B and total survivin was observed at 24-hr (Figure 2S-B).

Figure 2. siRNA-based silencing of survivin total and survivin 2B.

Two different siRNA were designed around the exon 2 to inhibit all survivin splice variants at the same time, and two additional siRNA were designed to inhibit only survivin 2B (Figure 2S). (A) Total RNA was isolated from siRNA-transfected cells to doing real-time PCR as described in the legend of Figure 1. Expression values were calculated relative to the C-siRNA. Columns represent the means of triplicates ± S.D. (B) A 100 μl aliquot of HEYA8.MDR cells (2 ×104 cells/ml) was plated in a 96-well plate, and 24-hr later cells were transfected with the siRNAs. Percentages were obtained after blank OD subtraction, taking the untreated cells values as 0% of cell growth inhibition. (**p<0.01, ***p<0.001) Columns represent the means of triplicates ± S.D. (C) Cells were treated as described in Figure 2B, but 24-hr after siRNA transfection, cells were incubated with docetaxel (DTX) for 72-hr. Values were obtained as described in Figure 2B. (*p<0.05, **p<0.01). Columns represent the means of triplicates ± S.D.

Dose-dependent growth inhibition was observed after 72-hr incubation of HEYA8.MDR cells with the T-survivin-siRNA or 2B-siRNA (Figure 2B). We also studied the effects of combining non-active doses of T-siRNA or 2B-siRNA with non-active doses of docetaxel (Figure 2C). Significant reduction in growth inhibition was observed with these combinations, synergism was observed at all concentrations tested (Figure 3S-A-B). Combination of an inactive dose of siRNA (25 nM), with different docetaxel concentrations induced additive growth inhibitory effects, even at 10 nM docetaxel (Figure 3S-C). Cell growth inhibition was also observed after transfection of HEYA8.MDR cells with other different siRNAs against total survivin and survivin 2B (Figure 4S). These results indicate that the growth inhibitory effects observed were indeed due to survivin-silencing.

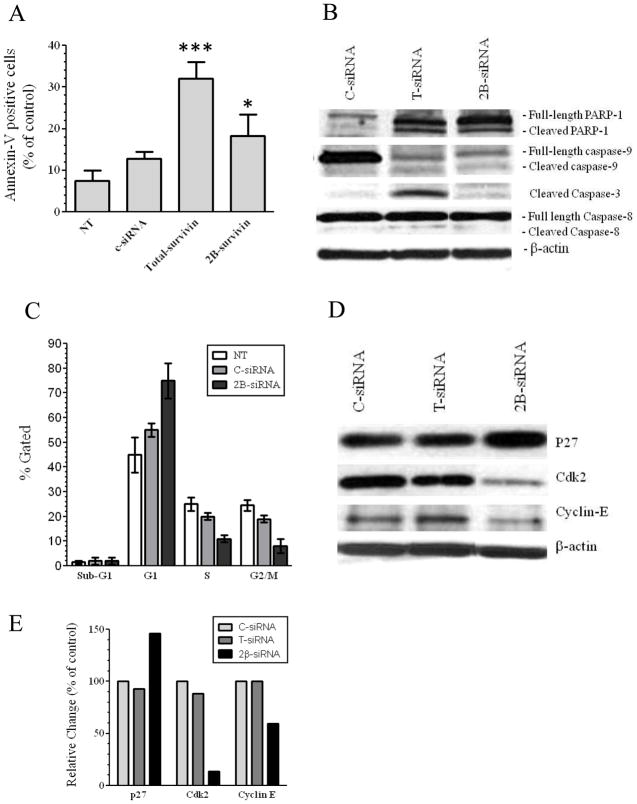

Effects of survivin-2B silencing on apoptosis and cell cycle progression

We next investigated whether the growth inhibition induced by T-siRNA or 2B-siRNA was due to apoptosis (Figure 3A). Transfection of HEYA8.MDR cells with T-siRNA induced up to 35% apoptosis while 2B-survivin silencing induced up to 15% apoptosis *p<0.01). These results were confirmed by Western blot analysis, which showed that silencing survivin 2B induced lower levels of PARP-1 cleavage and lower activation of caspase-9 and caspase-3 (Figure 3B) when compared with cells incubated with T-siRNA. No difference was observed in the cleavage product of caspase-8, between T-siRNA and 2B-siRNA. These latter effects were expected as caspase-8 is upstream of survivin in the apoptotic pathway (1, 2).

Figure 3. Apoptosis and cell cycle progression of survivin-targeted siRNA transfected cells.

1×105 HEYA8.MDR cells were seeded in a 6-well plate and 24-hr later 3 μg of each siRNA was mixed with the transfection reagent. The mix was incubated 10 min at RT and then added to the cells. (A) Seventy-two hours later apoptosis was measured with the FITC-apoptosis detection kit as described in the “Materials and Methods” section. (**p<0.01, ***p<0.001). Columns represent the means of triplicates ± S.D. (B) Seventy-two hours after siRNA-transfection another group of cells were collected to doing Western blots as described in “Materials and Methods”. The image is a representative experiment which was doing in triplicate. (C) Forty-eight hours after siRNA transfection HEYA8.MDR cells were used to test cell cycle progression with propidium iodide, with the CellQuestTM Pro software to calculate the number of cells in each stage of the cell cycle. Columns represent the means of triplicates ± S.D. (D) Forty-eight hours after siRNA transfection proteins were extracted for Western blots as describe in the “Materials and Methods” section. The image is a representative experiment which was doing in triplicate (E) Densitometric analysis of the band intensities showed in Figure 4D were expressed as percentages relative to control siRNA.

Survivin and its splice variants are known to play a central role during mitosis (1, 15, 34), thus, we also assessed whether cell cycle arrest is induced by survivin-2B silencing (Figure 3C). More than 80% of the HEYA8.MDR cells were arrested in G1 phase after 48-hr of transfection with 2B-siRNA (Figure 3C). Western blot analysis confirmed that key proteins required for transition from G1 to S phase (35–37) were downregulated Cyclin-E (40%) and cdk2 (80%)], while p27 which blocks cyclin E and cdk2 function (35) was upregulated (50%), in 2B-siRNA transfected cells (Figure 3D–E).

Therapeutic effect of 2B-siRNA-DOPC

DOPC-based nanoliposomes were used for the animal models as previously described (23, 24, 26, 30, 31). We first tested whether the siRNAs will silence the respective survivin isoforms in an orthotopic model of ovarian cancer (Figure 5S, See Materials and Methods). Mice were injected i.p. with 5μg siRNA per mouse of T-siRNA-DOPC or 2B-siRNA-DOPC. Mice were sacrificed 72-hr post-injection and the tumors were dissected. T-siRNA-DOPC, as expected, significantly reduced the expression of all isoforms, while 2B-siRNA-DOPC led to significant silencing of only survivin 2B.

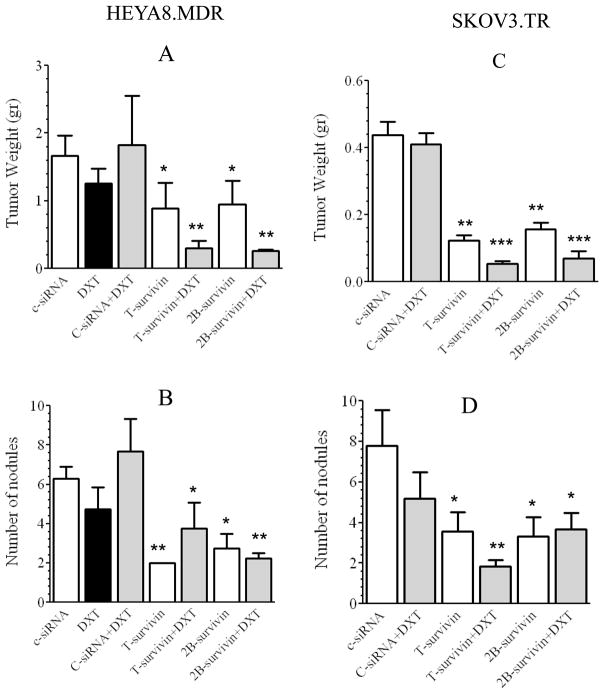

The anti-tumor effects of T-siRNA and 2B-siRNA as compared to C-siRNA were tested in HEYA8.MDR and in SKOV3.TR tumor-bearing mice (Figure 4). Tumor weight and number of nodules were assessed in all mice. Seven treatment groups (10 mice each) were studied, 1) C-siRNA-DOPC, 2) DTX alone, 3) C-siRNA-DOPC plus docetaxel (DTX), 4) T-siRNA-DOPC, 5) T-siRNA-DOPC plus DTX, 6) 2B-siRNA-DOPC, and 7) 2B-siRNA-DOPC plus DTX. SiRNA-DOPC (5 μg siRNA/injection) was injected twice a week and docetaxel (50 μg/injection) once a week (23, 24). All siRNA-DOPC treatments were given twice a week for 6 weeks. DTX by itself did not induce a significant effect on tumor growth (Figure 4A). Decreased tumor weight was observed in both T-siRNA-DOPC and 2B-siRNA-DOPC groups (*p< 0.05 for both, T-siRNA-DOPC, and 2B-siRNA-DOPC). Tumor weight was further reduced when DTX was added to T-siRNA-DOPC and 2B-siRNA-DOPC (**p<0.01 for both, T-siRNA-DOPC plus DTX, and 2B-siRNA-DOPC plus DTX). Similar results were obtained with treatment of SKOV3.TR-bearing mice with T-siRNA-DOPC and 2B-siRNA-DOPC alone or in combination with DTX (Figure 4C). T-siRNA-DOPC or 2B-siRNA-DOPC induced a significant decrease in the number of tumor nodules in both, HEYA8.MDR tumor bearing mice (**p< 0.01, Fig. 4B), and SKOV3.TR (**p < 0.01, Figure 4D). No further reduction in the number of tumor nodules was observed when DTX was combined with either T-siRNA-DOPC or 2B-siRNA-DOPC (Figure 4B and 4D).

Figure 4. In vivo therapeutic efficacy of total survivin-targeted siRNA in combination with docetaxel.

Nude mice were injected i.p. with HeyA8.MDR (A, B) or SKOV3.TR (C, D) cells and randomly allocated in the groups described in the “Materials and Methods” section. Therapy began 1 week after tumor cell inoculation. Mean tumor weight (A and C); number of nodules (B and D). (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001). Bars, SD.

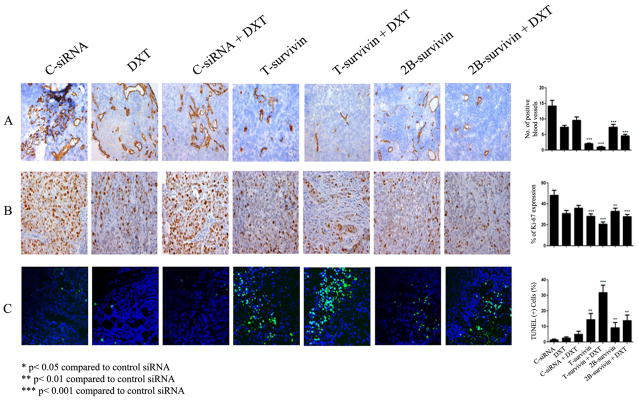

Effect of survivin silencing on angiogenesis, cell proliferation, and apoptosis

Since silencing of T-survivin induced cell growth inhibition and apoptosis in vitro and silencing of survivin 2B resulted in cell cycle arrest with few apoptotic events, we examined the effects of the siRNA-DOPC therapy on cell proliferation, apoptosis and microvessel density (MVD) in tumors dissected from the previous experiment. T-siRNA-DOPC and 2B-siRNA-DOPC treatment resulted in decreased MVD when compared to controls (Fig 5A), which was further decreased by combination treatment with docetaxel. Cell proliferation was assessed by staining for the nuclear marker Ki-67. T-siRNA-DOPC and 2B-siRNA-DOPC induced a significant (T-siRNA-DOPC (***p<0.001, and 2B-siRNA-DOPC **p<0.01) reduction in the Ki-67 index. TUNEL data analysis (Figure 5C) showed a significant induction of apoptosis in mice treated with T-siRNA-DOPC alone (*p<0.05), 2B-siRNA-DOPC alone (**p<0.01) or in combination with DTX (T-siRNA-DOPC (***p<0.001, and 2B-siRNA-DOPC **p<0.01). However higher apoptotic events were observed in T-siRNA-DOPC plus docetaxel group compared with 2B-siRNA-DOPC plus docetaxel group.

Figure 5. Effect of survivin-targeting siRNA s with or without docetaxel on cell proliferation, apoptosis and microvessel density.

A. MVD was determined after immunohistochemical peroxidase staining for CD31. B. Ki67 immunohistochemistry (IHC). Original magnification, 100x. Columns, mean percentage of Ki67-positive cells; bars, SD. Five animals per group and at least five fields per animal were counted. C. TUNEL IHC. Tumor sections from each group were stained for TUNEL. Representative slides from each group are shown. The number of apoptotic cells was counted. Columns, mean number of TUNEL-positive cells; bars, SD. Ten fields per slide and at least five slides per group (all from different animals) were counted.

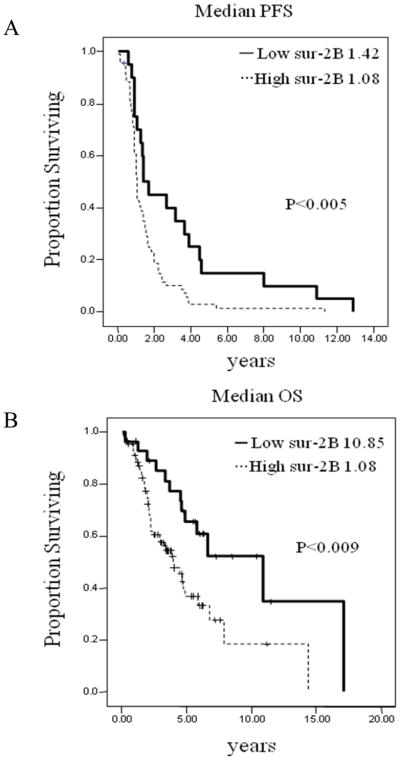

Survivin-2B expression in human ovarian carcinoma

Survivin and its splice variants are over-expressed in most cancers (14, 38) including ovarian cancer (11, 39). However most of these studies were performed by RT-PCR or immunohistochemistry (with an antibody against all survivin splice variants) and do not represent truly quantitative measures. The expression of survivin 2B is ovarian cancer has not been studied. Thus, we examined the messenger RNA expression levels of survivin 2B in 117 epithelial ovarian cancers obtained at primary debulking surgery by real-time PCR. Two-fold difference between the mRNA abundance for each sample and the mRNA control (normal ovarian epithelial cells) was considered as survivin 2B overexpression (27, 28, 40). Out of the 117 specimens, 24% (n=28) showed high levels of survivin 2B mRNA (Table S1). We found that survivin 2B overexpression was significantly (p<0.005) associated with progression free survival (PFS; Figure. 6A), and with overall survival (OS, p<0.009; Figure 6B). The relation between clinicopathological variables (stage, histology, grade, ascites and cytoreduction) and survivin-2B mRNA expression was also examined (Table 1S). Survivin-2B mRNA was significantly (p<0.07) higher in high stage tumors versus low stage disease. We also examined the effect of survivin-2B expression on patient survival in multivariable analysis. This analysis revealed that high survivin-2B expression (p=0.02) remained statistically significantly associated with patient survival after controlling for primary cytoreductive surgery, tumor stage and grade, histology, and patient age.

Figure 6. Kaplan-Meier survival curves.

(A) Progression free survival (PFS) and (B) overall survival (OS) based on the messenger mRNA survivin 2B levels obtained by SYBR-I-based real-time PCR.

Discussion

The key finding from our study is that siRNA-based silencing of the survivin splice variant 2B inhibits cell growth in vitro and reduces tumor growth in orthotopic models of taxane-resistant ovarian cancer. Furthermore, survivin-2B mRNA was detected in a substantial proportion of ovarian cancers, and was associated with poor of PFS and OS in ovarian cancer patients. Several reports have shown the role of survivin in drug resistance of ovarian cancer cells (11, 39, 41). However, the role of survivin-2B in taxane-resistant ovarian cancer cells had not been addressed. Our finding that survivin-2B is more abundant in taxane-resistant than in taxane-sensitive ovarian cancer cells, confirm previous results that each survivin splice variant could have specific intracellular roles as anti-apoptotic or cell cycle regulator proteins (14, 15, 17, 42). SiRNA-based silencing of survivin-2B induced similar growth inhibitory effects than silencing of all survivin splice variants at the same time, demonstrating that this survivin 2B could have a central role in cell growth, viability, and drug resistance of ovarian cancer cells. The cell cycle arrest in G1 upon survivin 2B silencing suggests that the main intracellular role of this isoform may be related to the regulation of cell cycle rather than apoptosis. In addition, our in vivo data confirmed that survivin 2B silencing induced lower apoptosis than silencing all survivin splice variants at the same time. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that survivin 2B is the only isoform that retains the C-terminal coiled coil domain necessary to the interaction with INCEP for the CPC formation during mitosis (14).

Earlier reports indicated that survivin 2B could have lost its anti-apoptotic function (15, 16, 19, 21) or even have a pro-apoptotic role (22). More recent survivin overexpression studies in human epithelial carcinoma A431 cell line performed by Knauer et al showed that survivin-3B was the only survivin isoform able to protected clones against cisplatin-induced apoptosis (18). Our data showed that silencing of survivin 2B in taxane-resistant ovarian cancer cells induced cell growth arrest in vitro and in vivo. In fact, the additional siRNA against survivin 2B that we used here was the one used by Ling et al (22) in which they observed an increase in cell resistance to paclitaxel-mediated growth inhibition of MCF-7 cells. Although our experiments were performed in different cell lines than those reported by others (16, 21, 22), our observation that siRNA-based silencing survivin 2B induced cell cycle arrest with minor apoptotic events (in vitro and in vivo) are more in agreement with a role of survivin 2B in the control of cell cycle progression (14). Survivin 2B silencing could lead to a mitotic catastrophe as previously observed after survivin deletion in vitro and in vivo, with survivin dominant-negative mutants (5, 8, 43, 44). The increasing levels of p27 and the decreased levels of cyclin-E and cdk2 with the concomitant arrest in G1 of survivin 2B-depleted HEYA8.MDR cells observed in our study correlates with the role of survivin 2B in the mitotic progression.

There is evidence suggesting that survivin induces drug resistance by stabilizing tubulin polymers (41, 45). The higher expression of mRNA in taxane-resistant compared with their taxane-sensitive counterparts ovarian cancer cells also demonstrated the central role of the survivin 2B splice variant in taxane resistance. Survivin 2B could promote cell survival by interacting with cell cycle-related kinases, including cdk2 and cyclin E (1). The increasing in sensitivity of taxane-resistant cells to docetaxel upon survivin 2B silencing suggest that targeting this survivin splice variant could induce important changes in microtubule dynamics and promote cell cycle arrest in drug-resistant ovarian cancer (41, 45).

The mRNA expression of survivin 2B has been assessed in different cancers (14, 46–48). However contrasting results were obtained regarding the correlation between survivin 2B expression levels and clinicopathological markers (14, 46–49). These contrasting results are mainly due to the use of non-specific primers to amplify specifically survivin 2B, or the use of semi-quantitative analysis of gel images obtained by RT-PCR (14, 49). This is the first report showing mRNA survivin 2B expression levels in ovarian cancer patients. The strong difference in the OS between ovarian cancer patients with high vs. low survivin 2B suggest that this splice variant could be used as a prognostic markers for ovarian cancer.

Although survivin is highly abundant in most cancers, growing evidence indicate that survivin could regulate the proliferation and survival of normal adult cells (50), especially those with continual renewal. On the basis of our results that silencing survivin 2B induces similar growth inhibition in vitro and in vivo than inhibiting all survivin splice variants at the same time, we propose the use of survivin 2B-siRNA-DOPC as a novel and specific anti-survivin therapy without compromising all intracellular pools of survivin in normal adult tissues.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1S. HEYA8.MDR and SKOV3.TR ovarian cancer cells are resistant to docetaxel and paclitaxel treatment. One hundred ml of cells (2×104 cells/ml) of (A) HEYA8 and HEYA8.MDR or (B) SKOV3ip1 and SKOV3.TR were seeded in a 96-well plate. 24-hr later, docetaxel (DTX) or paclitaxel (PTX) (each drug concentration was added in eight different wells) were added to the cells and incubated for 72-hr. The medium was then removed and 100 μl of the Alamar blue dye was added. OD values were obtained spectrophotometrically after 3-hr of dye incubation. Percentages were obtained after blank OD subtraction, taking the untreated cells values as 0% of cell growth inhibition. Columns represent the means of triplicates ± S.D. While 100 and 50 nM docetaxel (DTX) or paclitaxel (PTX) induced around 70% growth inhibition in taxane-sensitive ovarian cancer cells, these taxane doses resulted completely ineffective in the taxane-resistant ovarian cancer cells.

Figure 2S: (A) Splicing of the human survivin pre-mRNA produce five different splice variants. The empty boxes on the survivin-WT cartoon indicate the approximate location of the siRNAs designed to inhibit all survivin splice variants (T-siRNA). The black box on survivin 2B cartoon indicates where the location of the siRNA-targeted survivin 2B. (B) HEYA8.MDR cells were transfected with 3 μg of each siRNA. Cells were collected 24-hr, 48-hr and 72-h after siRNA transfection. SYBR-I-based real-time PCR was performed as described in the “Materials and Methods” section. Expression values were calculated with the ΔΔCt method and expressed relative to C-siRNA. Columns represent the means of triplicates ± S.D. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Figure 3S. (A–B). Isobologram analysis showing the T-siRNA and DTX (A), or 2B-siRNA and DTX (B) interaction effects in the cell growth of HeyA8 MDR cells. Solid line, concentrations of both drugs that cause a 40% inhibition of cell proliferation (IC40). Dots, the hypothetical amounts of both drugs required to cause the same decrease in cell proliferation as if the interactions were synergism. The number in the box, the interaction index calculated as described in “Materials and Methods”. (C) Combination of a non-active dose of siRNA plus different docetaxel doses induced cell growth inhibition. Cell growth measurements were performed as described in the “Materials and Methods” section. HEYA8.MDR cells were transfected with 25 nM of each siRNA and 24-hr later different DTX doses were added to the cells, and incubated for 72-hr. After this time-period Alamar-blue dye was used to calculate the percentage of growth inhibition. Errors bars represent the means of triplicates ± S.D. *p<0.05.

Figure 4S. Sequence of the additional siRNAs used in this study. Growth inhibition results after 72-hr transfection of HEYA8.MDR cells with the additional siRNAs.

Figure 5S. Real-time PCR with total RNA isolated from tumor tissues. RNA was isolated from HEYA8.MDR-bearing tumor tissues. SYBR-I-based real-time PCR was performed as described in the “Materials and Methods” section. Expression values were calculated with the ΔΔCt method and expressed relative to C-siRNA-treated mice. Columns represent the means of triplicates ± S.D. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Table 1S. Clinicopathological markers and survivin 2B mRNA expression levels in ovarian cancer samples.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was funded, in part, by the NIH (CA 110793, 109298, U54 CA096300, U54 CA151668, P50 CA083639, P50 CA098258, CA128797, RC2GM092599), the Ovarian Cancer Research Fund, Inc. (Program Project Development Grant), the DOD (OC073399, OC093146, BC085265), the Zarrow Foundation, and the Betty Anne Asche Murray Distinguished Professorship, and NCI institutional Core Grant CA16672, University of Puerto Rico Comprehensive Cancer Center seed funds to PEVM, the grant No. 61195 and scholarship No.165685 from the National Council for Science and Technology (CONACYT Mexico)

References

- 1.Altieri DC. Survivin, cancer networks and pathway-directed drug discovery. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nrc2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ambrosini G, Adida C, Altieri DC. A novel anti-apoptosis gene, survivin, expressed in cancer and lymphoma. Nat Med. 1997;3:917–21. doi: 10.1038/nm0897-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu G, Chai J, Suber TL, et al. Structural basis of IAP recognition by Smac/DIABLO. Nature. 2000;408:1008–12. doi: 10.1038/35050012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deveraux QL, Reed JC. IAP family proteins--suppressors of apoptosis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:239–52. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fortugno P, Beltrami E, Plescia J, et al. Regulation of survivin function by Hsp90. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13791–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2434345100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shiozaki EN, Chai J, Rigotti DJ, et al. Mechanism of XIAP-mediated inhibition of caspase-9. Mol Cell. 2003;11:519–27. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vader G, Kauw JJ, Medema RH, Lens SM. Survivin mediates targeting of the chromosomal passenger complex to the centromere and midbody. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:85–92. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yue Z, Carvalho A, Xu Z, et al. Deconstructing Survivin: comprehensive genetic analysis of Survivin function by conditional knockout in a vertebrate cell line. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:279–96. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200806118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pennati M, Folini M, Zaffaroni N. Targeting survivin in cancer therapy. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2008;12:463–76. doi: 10.1517/14728222.12.4.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tran J, Master Z, Yu JL, Rak J, Dumont DJ, Kerbel RS. A role for survivin in chemoresistance of endothelial cells mediated by VEGF. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:4349–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072586399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zaffaroni N, Pennati M, Colella G, et al. Expression of the anti-apoptotic gene survivin correlates with taxol resistance in human ovarian cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2002;59:1406–12. doi: 10.1007/s00018-002-8518-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang M, Latham DE, Delaney MA, Chakravarti A. Survivin mediates resistance to antiandrogen therapy in prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2005;24:2474–82. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ling X, Bernacki RJ, Brattain MG, Li F. Induction of survivin expression by taxol (paclitaxel) is an early event, which is independent of taxol-mediated G2/M arrest. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:15196–203. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310947200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sampath J, Pelus LM. Alternative splice variants of survivin as potential targets in cancer. Curr Drug Discov Technol. 2007;4:174–91. doi: 10.2174/157016307782109652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caldas H, Jiang Y, Holloway MP, et al. Survivin splice variants regulate the balance between proliferation and cell death. Oncogene. 2005;24:1994–2007. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahotka C, Wenzel M, Springer E, Gabbert HE, Gerharz CD. Survivin-deltaEx3 and survivin-2B: two novel splice variants of the apoptosis inhibitor survivin with different antiapoptotic properties. Cancer Res. 1999;59:6097–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noton EA, Colnaghi R, Tate S, et al. Molecular analysis of survivin isoforms: evidence that alternatively spliced variants do not play a role in mitosis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:1286–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508773200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knauer SK, Bier C, Schlag P, et al. The survivin isoform survivin-3B is cytoprotective and can function as a chromosomal passenger complex protein. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:1502–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahotka C, Liebmann J, Wenzel M, et al. Differential subcellular localization of functionally divergent survivin splice variants. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:1334–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stauber RH, Mann W, Knauer SK. Nuclear and cytoplasmic survivin: molecular mechanism, prognostic, and therapeutic potential. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5999–6002. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caldas H, Honsey LE, Altura RA. Survivin 2alpha: a novel Survivin splice variant expressed in human malignancies. Mol Cancer. 2005;4:11. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-4-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ling X, Cheng Q, Black JD, Li F. Forced expression of survivin-2B abrogates mitotic cells and induces mitochondria-dependent apoptosis by blockade of tubulin polymerization and modulation of Bcl-2, Bax, and survivin. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:27204–14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705161200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vivas-Mejia P, Benito JM, Fernandez A, et al. c-Jun-NH2-kinase-1 inhibition leads to antitumor activity in ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:184–94. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanaka T, Mangala LS, Vivas-Mejia PE, et al. Sustained small interfering RNA delivery by mesoporous silicon particles. Cancer Res. 2010;70:3687–96. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hwang JY, Mangala LS, Fok JY, et al. Clinical and biological significance of tissue transglutaminase in ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5849–58. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Halder J, Kamat AA, Landen CN, Jr, et al. Focal adhesion kinase targeting using in vivo short interfering RNA delivery in neutral liposomes for ovarian carcinoma therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:4916–24. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robles Y, Vivas-Mejia PE, Ortiz-Zuazaga HG, Felix J, Ramos X, Pena de Ortiz S. Hippocampal gene expression profiling in spatial discrimination learning. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2003;80:80–95. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7427(03)00025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1101–8. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mangala LS, Zuzel V, Schmandt R, et al. Therapeutic Targeting of ATP7B in Ovarian Carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3770–80. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Landen CN, Merritt WM, Mangala LS, et al. Intraperitoneal delivery of liposomal siRNA for therapy of advanced ovarian cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:1708–13. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.12.3468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Landen CN, Goodman BW, Katre AA, et al. Targeting Aldehyde Dehydrogenase Cancer Stem Cells in Ovarian Cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010 doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Landen CN, Jr, Chavez-Reyes A, Bucana C, et al. Therapeutic EphA2 gene targeting in vivo using neutral liposomal small interfering RNA delivery. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6910–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feleszko W, Mlynarczuk I, Balkowiec-Iskra EZ, et al. Lovastatin potentiates antitumor activity and attenuates cardiotoxicity of doxorubicin in three tumor models in mice. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:2044–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li F, Ambrosini G, Chu EY, et al. Control of apoptosis and mitotic spindle checkpoint by survivin. Nature. 1998;396:580–4. doi: 10.1038/25141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Masamha CP, Benbrook DM. Cyclin D1 degradation is sufficient to induce G1 cell cycle arrest despite constitutive expression of cyclin E2 in ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:6565–72. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suzuki A, Hayashida M, Ito T, et al. Survivin initiates cell cycle entry by the competitive interaction with Cdk4/p16(INK4a) and Cdk2/cyclin E complex activation. Oncogene. 2000;19:3225–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li P, Li C, Zhao X, Zhang X, Nicosia SV, Bai W. p27(Kip1) stabilization and G(1) arrest by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) in ovarian cancer cells mediated through down-regulation of cyclin E/cyclin-dependent kinase 2 and Skp1-Cullin-F-box protein/Skp2 ubiquitin ligase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:25260–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311052200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li F. Role of survivin and its splice variants in tumorigenesis. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:212–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liguang Z, Peishu L, Hongluan M, et al. Survivin expression in ovarian cancer. Exp Oncol. 2007;29:121–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Merritt WM, Lin YG, Han LY, et al. Dicer, Drosha, and outcomes in patients with ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2641–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0803785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O’Connor DS, Wall NR, Porter AC, Altieri DC. A p34(cdc2) survival checkpoint in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:43–54. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Badran A, Yoshida A, Ishikawa K, et al. Identification of a novel splice variant of the human anti-apoptopsis gene survivin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;314:902–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.12.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosa J, Canovas P, Islam A, Altieri DC, Doxsey SJ. Survivin modulates microtubule dynamics and nucleation throughout the cell cycle. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:1483–93. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-08-0723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uren AG, Wong L, Pakusch M, et al. Survivin and the inner centromere protein INCENP show similar cell-cycle localization and gene knockout phenotype. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1319–28. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00769-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheung CH, Chen HH, Kuo CC, et al. Survivin counteracts the therapeutic effect of microtubule de-stabilizers by stabilizing tubulin polymers. Mol Cancer. 2009;8:43. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-8-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamada Y, Kuroiwa T, Nakagawa T, et al. Transcriptional expression of survivin and its splice variants in brain tumors in humans. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:738–45. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.99.4.0738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Suga K, Yamamoto T, Yamada Y, Miyatake S, Nakagawa T, Tanigawa N. Correlation between transcriptional expression of survivin isoforms and clinicopathological findings in human colorectal carcinomas. Oncol Rep. 2005;13:891–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kappler M, Kohler T, Kampf C, et al. Increased survivin transcript levels: an independent negative predictor of survival in soft tissue sarcoma patients. Int J Cancer. 2001;95:360–3. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20011120)95:6<360::aid-ijc1063>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Espinosa M, Cantu D, Herrera N, et al. Inhibitors of apoptosis proteins in human cervical cancer. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fukuda S, Pelus LM. Regulation of the inhibitor-of-apoptosis family member survivin in normal cord blood and bone marrow CD34(+) cells by hematopoietic growth factors: implication of survivin expression in normal hematopoiesis. Blood. 2001;98:2091–100. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.7.2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure 1S. HEYA8.MDR and SKOV3.TR ovarian cancer cells are resistant to docetaxel and paclitaxel treatment. One hundred ml of cells (2×104 cells/ml) of (A) HEYA8 and HEYA8.MDR or (B) SKOV3ip1 and SKOV3.TR were seeded in a 96-well plate. 24-hr later, docetaxel (DTX) or paclitaxel (PTX) (each drug concentration was added in eight different wells) were added to the cells and incubated for 72-hr. The medium was then removed and 100 μl of the Alamar blue dye was added. OD values were obtained spectrophotometrically after 3-hr of dye incubation. Percentages were obtained after blank OD subtraction, taking the untreated cells values as 0% of cell growth inhibition. Columns represent the means of triplicates ± S.D. While 100 and 50 nM docetaxel (DTX) or paclitaxel (PTX) induced around 70% growth inhibition in taxane-sensitive ovarian cancer cells, these taxane doses resulted completely ineffective in the taxane-resistant ovarian cancer cells.

Figure 2S: (A) Splicing of the human survivin pre-mRNA produce five different splice variants. The empty boxes on the survivin-WT cartoon indicate the approximate location of the siRNAs designed to inhibit all survivin splice variants (T-siRNA). The black box on survivin 2B cartoon indicates where the location of the siRNA-targeted survivin 2B. (B) HEYA8.MDR cells were transfected with 3 μg of each siRNA. Cells were collected 24-hr, 48-hr and 72-h after siRNA transfection. SYBR-I-based real-time PCR was performed as described in the “Materials and Methods” section. Expression values were calculated with the ΔΔCt method and expressed relative to C-siRNA. Columns represent the means of triplicates ± S.D. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Figure 3S. (A–B). Isobologram analysis showing the T-siRNA and DTX (A), or 2B-siRNA and DTX (B) interaction effects in the cell growth of HeyA8 MDR cells. Solid line, concentrations of both drugs that cause a 40% inhibition of cell proliferation (IC40). Dots, the hypothetical amounts of both drugs required to cause the same decrease in cell proliferation as if the interactions were synergism. The number in the box, the interaction index calculated as described in “Materials and Methods”. (C) Combination of a non-active dose of siRNA plus different docetaxel doses induced cell growth inhibition. Cell growth measurements were performed as described in the “Materials and Methods” section. HEYA8.MDR cells were transfected with 25 nM of each siRNA and 24-hr later different DTX doses were added to the cells, and incubated for 72-hr. After this time-period Alamar-blue dye was used to calculate the percentage of growth inhibition. Errors bars represent the means of triplicates ± S.D. *p<0.05.

Figure 4S. Sequence of the additional siRNAs used in this study. Growth inhibition results after 72-hr transfection of HEYA8.MDR cells with the additional siRNAs.

Figure 5S. Real-time PCR with total RNA isolated from tumor tissues. RNA was isolated from HEYA8.MDR-bearing tumor tissues. SYBR-I-based real-time PCR was performed as described in the “Materials and Methods” section. Expression values were calculated with the ΔΔCt method and expressed relative to C-siRNA-treated mice. Columns represent the means of triplicates ± S.D. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Table 1S. Clinicopathological markers and survivin 2B mRNA expression levels in ovarian cancer samples.