Abstract

Background

At least half a million women are victims of intimate partner violence in the United States annually, resulting in substantial harm. However, the etiology of violence to intimate partners is not well understood. Witnessing such violence in childhood has been proposed as a principal cause of adulthood perpetration, yet it remains unknown whether the association between witnessing intimate partner violence and adulthood perpetration is causal.

Method

We conducted a propensity-score analysis of intimate partner violence perpetration to determine whether childhood witnessing is associated with perpetration in adulthood, independent of a wide range of potential confounding variables, and therefore might be a causal factor. We used data from 14,564 U.S. men ages 20 and older from the 2004–2005 wave of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions.

Results

Nearly 4% of men reported violent behavior toward an intimate partner in the past year. In unadjusted models, we found a strong association between childhood witnessing of intimate partner violence and adulthood perpetration (for witnessing any intimate partner violence, risk ratio [RR] = 2.6 [95% confidence interval = 2.1–3.2]; for witnessing frequent or serious violence, 3.0 [2.3–3.9]). In propensity-score models, the association was substantially attenuated (for witnessing any intimate partner violence, adjusted RR = 1.6 [1.2–2.0]; for witnessing frequent or serious violence, 1.6 [1.2–2.3]).

Conclusions

Men who witness intimate partner violence in childhood are more likely to commit such acts in adulthood, compared with men who are otherwise similar with respect to a large range of potential confounders. Etiological models of intimate partner violence perpetration should consider a constellation of childhood factors.

Intimate partner violence is a serious public health issue. In the United States, at least half a million women are victims of intimate partner violence annually—4.3 per thousand women.1 Women assaulted by an intimate partner experience significant health consequences including injury, chronic pain, gastrointestinal problems, sexually transmitted infections, depression, suicidality, post-traumatic stress disorder, and death.2 Efforts to understand the etiology of intimate partner violence are critical to reduce this health threat.

Though many studies have examined consequences of intimate partner violence victimization, relatively few studies have focused on risk factors for perpetrating such violence. Perpetration has been associated with low socioeconomic status,3 substance use,3 mental illness,3,4 and poor parenting in childhood.4 The central theme in this literature, however, is the possible intergenerational transmission of violence, whereby witnessing intimate partner violence in childhood4-6 or experiencing physical abuse7 leads to perpetration of intimate partner violence in adulthood.

Three strands of evidence support a causal relationship between witnessing intimate partner violence in childhood and perpetrating such violence in adulthood: (1) consistency of association across a large number of studies in different populations; (2) theoretical plausibility; and (3) evidence supporting the mechanisms described in the theoretical models.

The association between witnessing intimate partner violence and later perpetration has been found in multiple studies in diverse settings,6,8 although some studies found no association.9,10 A meta-analysis of 39 studies found the strength of the association to be small-to-moderate.6 Theoretical models further support a causal relationship between witnessing intimate partner violence and later perpetration. Social cognitive models emphasize that children learn to perpetrate intimate partner violence by observing and imitating such violence in their childhood homes, without developing nonviolent conflict resolution and verbal skills.11 Social-information-processing models12 focus on the effects of witnessing violence on violent perpetration through increased attribution of hostile intent to a partner, generation of violence as a possible response, and belief in positive outcomes of violence.12 Attachment theory hypothesizes that witnessing intimate partner violence disrupts children’s attachment to parents, leading to emotional dysregulation, abandonment anxiety, and dependent attachment style in adulthood.5 Finally, researchers hypothesize that exposure to intimate partner violence can cause mental illness, including borderline personality organization, post-traumatic stress disorder, and antisocial personality disorder, leading to cognitive problems, emotional dysregulation, and high levels of anger.13

Research supports these causal pathways, indicating that boys who witness intimate partner violence are more likely to approve of violence, to believe that violence improves one’s reputation, and to justify their own violent behavior, compared with boys who have not witnessed such violence.14 Children exposed to intimate partner violence have high negative emotional reactivity, behavioral dysregulation, externalizing problems,15 and lower IQs16 than unexposed children. In turn, evidence from adults indicates that many of these factors relate to adult perpetration of intimate partner violence, as perpetrators are more likely to attribute hostile intent, to view violence as acceptable,17 and to have lower verbal and social skills and poorer marital communication than nonperpetrators.17,18

Studies also suggest that negative effects of witnessing violence may be mitigated with high levels of family emotional support. Emotional support in childhood may protect against future violence perpetration5 by buffering the negative effects of witnessing violence on internalizing and externalizing problems, substance use,19 personality, and violent behavior.20 However, this possible protective effect has not been specifically assessed for the relationship between witnessing intimate partner violence and perpetration of such violence.

Despite the empirical and conceptual bases supporting a causal relationship between intimate partner violence witnessing and perpetration, most past estimates adjust for few factors associated with witnessing that may also cause later perpetration. Therefore, published associations may not represent causal effects. Instead, the observed association may be explained by confounding factors—prior causes associated with both witnessing and perpetrating intimate partner violence. Potential confounding factors include parental criminality, mental illness, tendency to violence, antisocial personality disorder,10,21,22 alcohol and drug problems,21,23 and low socioeconomic status. 10,23 These parental traits and behaviors may increase both the risk of the child witnessing intimate partner violence and the risk of the child’s exposure to physical, sexual, and psychologic abuse,7,10,14,21 neglect,7 and community violence,20 experiences which may increase the likelihood that the child will perpetrate intimate partner violence in adulthood. Reviews of the literature have emphasized the need for more sophisticated methodologies to determine the independent effects of witnessing intimate partner violence and other potentially confounding childhood factors on later perpetration.13,14,23,24 Moreover, the validity of studies of the impact of witnessing intimate partner violence has further been questioned because many studies rely on shelter or clinic samples10,14,24 with small numbers of male perpetrators.10

Given this limited state of knowledge and the need to better estimate the causal impact of witnessing intimate partner violence in childhood on subsequent perpetration, we attempt to estimate the causal effect of witnessing such violence in childhood on perpetration in adulthood using propensity-score analysis. This approach has previously been used to examine the effect of exposure to community violence on gun-carrying and perpetration of community violence.25 Propensity-score analysis entails comparing perpetration outcomes between groups of men who have and have not witnessed intimate partner violence but who are otherwise comparable with respect to a wide range of potential confounders.

Propensity-score modeling is particularly useful in situations where the distribution of some confounders between those with and without the exposure of interest overlap only slightly. In these situations, estimates of causal effects from regression analyses are determined mostly by extrapolation, and the researcher may not be aware of the limited overlap in characteristics of the exposed and unexposed groups. Lack of overlapping characteristics threatens the assumption of exchangeability between the exposed and unexposed upon which causal inference rests. However, stratifying on the propensity to be exposed to the causal factor—in this case, witnessing intimate partner violence—before conducting regression analysis largely eliminates the problem of extrapolation. 26 Furthermore, if there are strata with no overlap between exposed and unexposed, propensity-score analysis may help researchers identify the subpopulation to which their estimates apply.27 To assess whether emotional support protect against the effects of witnessing intimate partner violence, we exclude emotional support from the propensity-score model and include it as a distinct variable in models of intimate partner violence perpetration.

METHODS

Data

We used data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, which applied a multistage sampling design to yield a representative sample of the civilian, noninstitutionalized population, 18 years and older, residing in the United States at Wave 1, conducted in 2001–2002 (81% response rate).28,29 The current analysis uses data primarily from the Wave 2 follow-up interview (response rate, 87%; cumulative response, 70%),29 these interviews, conducted in 2004–2005, approximately 3 years after the original survey, assessed intimate-partner-violence perpetration and childhood witnessing. For respondents present in Wave 2, we also included data from Wave 1 regarding childhood family structure, and familial liability for antisocial personality disorder and alcoholism, which were not assessed at Wave 2. The sample was restricted to men (n = 14,564),24 among whom violent behaviors are more often harmful.

Measures

Outcome: Perpetration of Intimate Partner Violence

Respondents who were married or in a romantic relationship in the past year were asked about use of physical force with their partner. The following statement was read: “No matter how well a couple gets along, there are times when they disagree, get annoyed, or just have fights.” Six questions were then asked about the frequency of the respondent’s use of force with their partner, and their partner’s use of force with them in the past year. Respondents were coded as perpetrators if they had: (1) pushed, grabbed, or shoved; (2) slapped, kicked, bitten, or punched; (3) threatened with a weapon such as a gun or knife; (4) cut or bruised; (5) forced sex; or (6) injured their partner enough to require medical care.

These questions are taken from the Conflict Tactics Scales,30 which have been validated in the general population using couples’ reports on their own perpetration and victimization. A validation study using these items found very good internal consistency (Cronbach alpha = 0.8), as well as moderate agreement between men’s reports of any perpetration and their female partners’ reports of any victimization (Cohen kappa = 0.5), with 39% of men reporting perpetrating any of the behaviors and 41% of women reporting being victimized by any of the behaviors. On average, men reported 18% fewer perpetrations (0.1 standard deviations) than their female partners reported victimizations.31 Because several studies of concordance of intimate partner violence have shown that perpetrators report fewer acts of violence than their partner-victims, we used the most inclusive measure of perpetration, coding men as perpetrators if they reported any such behaviors in the past 12 months. Although only men in a relationship could (by definition) behave violently towards an intimate partner, we included all men in the analyses in case the likelihood of being in a relationship was influenced by childhood witnessing.

Exposure: Childhood Witnessing of Male-to-female Intimate Partner Violence

Respondents were asked about the behavior of their father, stepfather, or mother’s boyfriend toward their mother, stepmother, or father’s girlfriend when they were younger than 18 years old. Respondents were asked how often he: (1) pushed, grabbed, slapped, or threw something at her; (2) kick, bit, hit her with a fist, or hit her with something hard; (3) repeatedly hit her for a few minutes; or (4) threatened her with a knife or gun or used a knife or gun to hurt her.30 Respondents reporting any of these behaviors were considered to have witnessed male-to-female intimate partner violence.31

Because exposure to repeated or more severe intimate partner violence may have correspondingly-larger effects in a dose-response fashion, we also identified a subset of men who had been exposed to frequent or serious intimate partner violence. Men were considered to have been exposed to frequent or serious intimate partner violence if their mother’s partner fairly often or very often pushed, grabbed, slapped or threw something at her; sometimes, fairly often, or very often kick, bit, hit her with a fist, or hit her with something hard; or ever repeatedly hit her, or threatened or hurt her with a knife or gun. In the interview, respondents were asked about childhood witnessing before being asked about past-year perpetration, and they did not know they would be asked about perpetration. Therefore their response about witnessing could not have been biased by their response about perpetrating.

Covariates: Childhood Circumstances and Adverse Events

All possible childhood confounders available in the dataset were considered. Variables were excluded if they could be sequelae of witnessing intimate partner violence. Because we were interested in isolating the effects of witnessing intimate partner violence, we included variables in the propensity score that could be caused by intimate partner violence and might increase the child’s risk of perpetration as long as they were unlikely to be caused by witnessing such violence. For example, mother’s mental illness, divorce, and father’s imprisonment could be outcomes of intimate partner violence by the father and could increase the child’s risk of perpetration but are unlikely to be caused by the child being witness to the violence.

Neglect, Psychological Abuse, Physical Abuse, and Sexual Abuse

Childhood neglect was measured by summing responses to 5 questions regarding frequency of different types of neglect. Respondents in the highest 10% were scored “high,” those with lower levels were scored “some,” and those without neglect were scored “none.” Childhood psychologic abuse was similarly measured with 3 questions about caregivers saying hurtful things or threatening violence. Childhood physical abuse was measured with 2 items regarding the frequency of caregivers pushing, hitting, or bruising the respondent.30 The respondent was considered to have experienced childhood sexual abuse if, before the age of 18, he experienced any of the following unwanted actions: was touched in a sexual way, was made to touch someone’s body in a sexual way, or someone had intercourse with him.32

Family Characteristics

Family structure before age 18 was measured with 6 dichotomous variables reflecting whether the respondent had never lived with at least 1 biologic parent, had never lived with his biologic father, or was raised by adoptive parents, foster parents, relatives, or in an institution. Family-related events, including parental divorce or separation, living with a stepparent, and death of a parent were each measured with 2 dichotomous variables reflecting whether these events occurred before age twelve or at age twelve or later, or did not occur during childhood. Six circumstances regarding parents or other adults living in the home during childhood were each coded dichotomously: problem drinking, problem drug use, imprisonment, mental illness, suicide attempt, and completed suicide.

Traumatic Events

Eighteen events were each measured with 2 dichotomous variables reflecting whether these events occurred before age 12, at age 12 or later, or did not occur during childhood. Events included physical attack or serious neglect by a caregiver, sexual assault, serious accidents, illnesses, or natural disasters, unexpected death of a loved one, and war-related events. Items regarding neglect, physical abuse, and sexual abuse overlap with the scales measuring these experiences described above, but because the phrasing of these questions was different, we included them in the propensity score.

Familial Liability for Antisocial Personality Disorder and Alcoholism

Familial liability for antisocial personality disorder was assessed with the Family History sections of the interview. Proportion of first-degree relatives with antisocial personality disorder was calculated by dividing number of first-degree relatives affected by total number of first-degree relatives. Proportion of second-degree relatives with antisocial personality disorder was calculated by dividing number of second-degree relatives affected by total number of second degree relatives.33 Familial liability for alcoholism was calculated similarly.

Demographic Variables

Based on respondents’ selections of their race and ethnic origin, and following US Census Bureau algorithm, the survey classified race/ethnicity in the following preferential order: Hispanic, or non-Hispanic: Black, American Indian/Native Alaskan, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, Asian, or White. Age at interview was continuous. Immigrant status was US-born or foreign-born. Childhood poverty was measured dichotomously based on receipt of welfare, aid, or food stamps.

Potential Protective Factor: Childhood Family Emotional Support

Childhood emotional support was measured as high, medium, or low. The frequencies of 5 types of support from family members were summed: someone wanted me to be a success; someone helped me feel special; someone believed in me; my family was a source of strength; and I was part of a close-knit family. Respondents scoring in the lowest 10% of this scale were coded as having low support (scoring below 12 of 20), those in the next 25% were considered to have medium support (12–16), and the remaining were considered to have high support (17–20).

Analyses

Construction of Propensity Score for Witnessing Intimate Partner Violence

We constructed 2 propensity-score models predicting probability of witnessing any intimate partner violence in childhood and probability of witnessing frequent or serious intimate partner violence in childhood from all measures of circumstances and events before age 18 associated with witnessing violence.34 For the model of witnessing frequent or serious violence, men who had been exposed to mild violence were dropped, and the estimated propensity scores were calculated from a logistic model with the witness of serious violence as the dependent variable.35 For each exposure (any intimate partner violence, and frequent or serious violence), respondents were stratified by quintiles of estimated propensity score.36 We then checked whether potential childhood confounders were balanced for respondents exposed and unexposed to witnessing intimate partner violence within strata of estimated propensity-score quintiles by comparing the standardized difference between exposed and unexposed subjects.34,37 Standardized difference has been proposed as a good measure of balance because it is unaffected by sample size.34 Interaction terms were added to and removed from the propensity score models iteratively to attain the best balance.38

Models

First, we examined the unadjusted association of witnessing any intimate partner violence or witnessing frequent or serious intimate partner violence with adult intimate partner violence perpetration, using log-linear regression models. Next, to assess the effect of the 2 types of intimate partner violence witnessing on perpetration, we used separate log-linear regression models for any witnessing, and for frequent or serious witnessing, to calculate the relative risk of perpetrating intimate partner violence in adulthood for respondents who had or had not actually witnessed intimate partner violence in childhood, within strata of estimated propensity score. Specifically, we fitted log-linear regression models with perpetration as the dependent variable, and with indicator variables for witnessing and for 4 of the 5 propensity score quintiles as predictors. We compared risk ratios (RRs) and their associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) within strata of propensity score to check for homogeneity of risk ratios across strata. For models of witnessing frequent or serious intimate partner violence, the comparison group was respondents who had not witnessed any intimate partner violence. We included childhood emotional support in models to see if it protected against perpetration.26

All analyses were conducted using 5 sets of imputed data. Multiple imputation was implemented with iveWare software.39,40 Percent missing were 1.2% for the exposure (witnessing intimate partner violence) 0.4% for the outcome (perpetration) and 0.8% for the protective factor (support). Among the covariates, the maximum missing was 1.1%, except for the measures of family alcoholism and antisocial personality disorder, which were created from 3 sets of questions about relatives and their behaviors. For first-degree relatives, 5.3% of respondents were missing data on alcoholism and 10.0% were missing data on antisocial personality disorder. For second-degree relatives, 25.3% of respondents were missing data on alcoholism and 27.2% were missing information on antisocial personality disorder. All statistical analyses were conducted using SUDAAN software41 to account for the nested sampling design of the original survey (which may result in correlated responses), to weight the data to reflect the US population, and to combine results from the 5 imputed datasets.28

RESULTS

Of men married or in a romantic relationship (86% of all men), 14% of men (n = 2185) reported having witnessed any intimate partner violence in childhood, 8% (n = 1119) reported having witnessed frequent or serious violence, and 4% (n = 514) reported having perpetrated intimate partner violence in the past year.

Adverse childhood circumstances were far more prevalent among respondents who reported witnessing any intimate partner violence, or frequent or serious violence, than among those who did not witness violence (Table 1). As a group, respondents exposed to any intimate partner violence had 4–7 times the prevalence of psychological, physical, and sexual abuse, and of neglect, than respondents unexposed to violence. Respondents who witnessed any violence also had more than 3 times the prevalence of having a parent or adult in the home with problem drug use, with problem alcohol use, or who was imprisoned, compared with nonwitnesses. Finally, witnesses of any intimate partner violence also had more than 2 times the prevalence of having a first-degree relative with antisocial personality disorder, having biologic parents divorce, and experiencing poverty in childhood, compared with nonwitnesses. Men who witnessed frequent or serious violence also had a higher prevalence of nearly every adverse childhood event.

TABLE 1.

Prevalencea of Adverse Childhood Circumstances and Events and Demographic Variables by the Reported Witness of Male-to-female Intimate Partner Violence in Childhood, US Men Ages 20 Years and Older (n = 14,564)

| Did Not Witness Intimate Partner Violence in Childhood (n = 12,379) | Witnessed Any Intimate Partner Violence in Childhood (n = 2185) | Witnessed Frequent or Serious Intimate Partner Violence in Childhood (n = 1119) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abuse and neglectb | |||

| Neglect | 6.1 | 32.1 | 43.9 |

| Psychologic abuse | 5.3 | 36.8 | 48.2 |

| Physical abuse | 6.8 | 40.1 | 53.0 |

| Sexual abuse | 3.8 | 14.9 | 19.9 |

| Problems of parent/adult in home | |||

| Problem alcohol user | 15.2 | 53.2 | 63.9 |

| Problem drug user | 3.6 | 11.0 | 14.5 |

| Mental illness | 4.2 | 9.8 | 11.2 |

| Imprisoned | 5.0 | 20.5 | 28.0 |

| Attempted suicide | 2.9 | 7.4 | 9.2 |

| Committed suicide | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.6 |

| Family liability for antisocial personality disorder | |||

| Any first-degree relatives | 12.8 | 31.7 | 37.7 |

| Any second-degree relatives | 11.4 | 21.1 | 23.3 |

| Family liability for alcoholism | |||

| Any first-degree relatives | 26.5 | 55.1 | 62.7 |

| Any second-degree relatives | 37.7 | 54.0 | 57.9 |

| Family events | |||

| Biologic parents stopped living together | 13.4 | 30.8 | 34.3 |

| Started living with a step-parent | 10.0 | 23.3 | 25.8 |

| Death of step-parent | 0.3 | 0.9 | 1.4 |

| Death of biological or adoptive parent | 8.8 | 9.4 | 11.4 |

| Traumatic events | |||

| Sexual assault or molestation | 1.9 | 6.2 | 8.2 |

| Physical attack by caregiver | 1.4 | 12.7 | 21.3 |

| Serious neglect by caregiver | 1.5 | 9.7 | 15.1 |

| Physical attack by other (not caregiver or romantic partner) | 6.6 | 14.8 | 16.7 |

| Kidnapped | 0.2 | 0.6 | 1.0 |

| Stalked | 0.5 | 1.4 | 2.2 |

| Mugged | 5.1 | 13.1 | 13.9 |

| Life-threatening accident | 8.3 | 13.6 | 15.0 |

| Life-threatening illness | 4.8 | 6.9 | 6.1 |

| Natural disaster | 7.1 | 10.7 | 12.5 |

| Civilian in a war zone | 1.1 | 0.7 | 1.1 |

| Refugee | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| Terrorist attack, self or someone close | 0.5 | 0.9 | 1.1 |

| See someone killed, see a dead body | 11.5 | 19.5 | 21.0 |

| Someone close die unexpectedly | 12.8 | 19.2 | 21.3 |

| Someone close illness, accident, injury | 13.2 | 19.2 | 19.5 |

| Someone close other traumatic event | 3.7 | 8.6 | 8.7 |

| Self other traumatic event | 0.8 | 1.9 | 2.5 |

| Family structure | |||

| Never lived with a biologic parent | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.3 |

| Never lived with biologic father | 10.6 | 14.6 | 16.5 |

| Raised by adoptive parents | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.7 |

| Raised by foster parents | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Raised by relatives | 0.9 | 1.2 | 1.3 |

| Raised in other circumstances | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Demographic factors | |||

| Poverty in childhood | 10.8 | 24.9 | 30.5 |

| Minority race/ethnicity | 27.7 | 35.5 | 47.9 |

| Born in US | 85.5 | 86.6 | 85.3 |

| Age at interview (years); mean | 47.4 | 46.1 | 46.5 |

Percent reporting this characteristic, unless otherwise noted.

Percent in top decile.

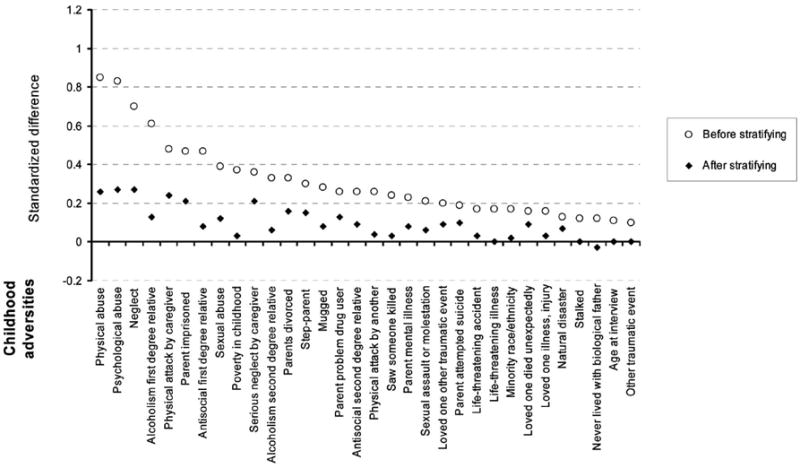

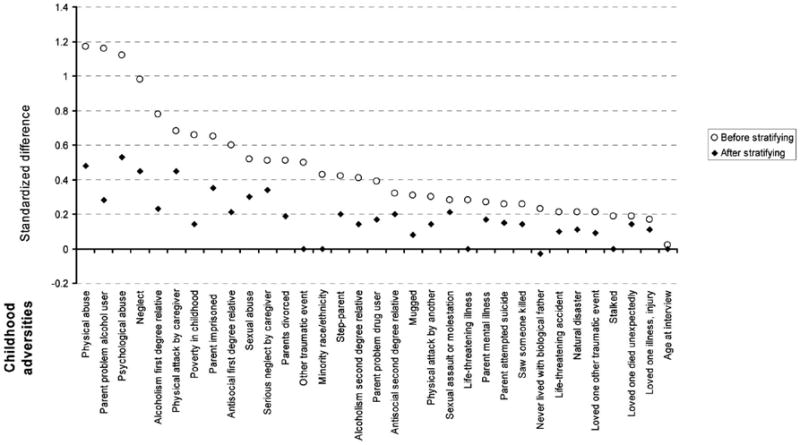

After stratifying on propensity score, the balance between potential confounders in the exposed and unexposed groups was substantially improved (Figs. 1, 2; eTable, http://links.lww.com/EDE/A425). The mean standardized difference between men who reported having been exposed to any intimate partner violence and unexposed men was 0.3, indicating that, on average across variables, the group means differed by 0.3 standard deviations. After stratifying on estimated propensity-score quintiles, the average difference between the exposed and unexposed was 0.1 standard deviations. For men exposed to frequent or serious violence, the initial imbalance was 0.5 standard deviations. After stratifying, the imbalance was 0.2 standard deviations. Because potentially-meaningful imbalances remained (based on suggested criteria that standardized differences greater than 0.1 may indicate possibly important imbalance42), we examined propensity score-adjusted models that also included potential confounders with imbalance greater than 0.1 to see if this altered our results.26

FIGURE 1.

Standardized difference in prevalence of childhood adversities between exposed and unexposed to witnessing any intimate partner violence in childhood, before and after stratifying by propensity score.

FIGURE 2.

Standardized difference in prevalence of childhood adversities between exposed and unexposed to witnessing serious or frequent intimate partner violence in childhood, before and after stratifying by propensity score.

We found a strong association between reported childhood intimate partner violence witnessing and reported adult intimate partner violence perpetration in unadjusted models (any witnessing, RR = 2.6 [95% CI = 2.1–3.2]; frequent or serious witnessing, 3.0 [2.3–3.9]). Because only 8 men had witnessed frequent or serious violence in the lowest stratum of propensity score for serious witnessing (0.8% of all witnesses of serious violence), we excluded this stratum from the propensity-score-stratified model with witnessing serious intimate partner violence. Our estimates of this association therefore do not pertain to the fewer than 1% of witnesses who are least likely to witness serious violence (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Number of Men Reporting Having Perpetrated and Not Perpetrated Intimate-partner-violence and Risk Ratios, by Estimated Propensity Score Stratum and Childhood Intimate Partner Violence Witnessing, US Men Ages 20 Years and Older (n = 14,564)a

| Propensity to Have Witnessed Intimate Partner Violence | Witnessed Intimate Partner Violence

|

RR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 12,379)

|

Yes (n = 2185b)

|

||||

| Did Not Perpetrate Intimate Partner Violence No. | Penetrated Intimate Partner Violence No. | Did Not Perpetrate Intimate Partner Violence No. | Penetrated Intimate Partner Violence No. | ||

| Any intimate partner violence witnessing | |||||

| 0.006–0.022 | 2838 | 47 | 27 | 0 | 0 |

| 0.022–0.040 | 2782 | 60 | 70 | 1 | 0.9 (0.1–7.1) |

| 0.040–0.092 | 2641 | 75 | 187 | 11 | 2.3 (1.1–4.7) |

| 0.092–0.240 | 2354 | 94 | 434 | 32 | 2.0 (1.3–3.2) |

| 0.240–0.970 | 1406 | 84 | 1312 | 111 | 1.3 (0.9–1.9) |

| Frequent or serious intimate partner violence witnessing | |||||

| 0.001–0.007 | 2650 | 41 | 8 | 0 | |

| 0.007–0.013 | 2630 | 51 | 19 | 0 | 0 |

| 0.013–0.027 | 2581 | 77 | 40 | 3 | 3.1 (0.9–10.5) |

| 0.027–0.086 | 2471 | 96 | 127 | 6 | 1.5 (0.6–3.9) |

| 0.086–0.987 | 1688 | 95 | 832 | 84 | 1.6 (1.1–2.3) |

Adjusted for emotional support.

Two thousand one hundred eighty-five men were categorized as having witnessed any intimate partner violence (top half of table); 1119, as having witnessed frequent or serious intimate partner violence (bottom half of table).

In the stratified model, the reported witness of any violence remained associated with perpetration, but the effect was attenuated (adjusted RR = 1.6 [1.2–2.0]). The effect was also attenuated for witness of frequent or serious violence (1.6 [1.2–2.3]). We did not find evidence of heterogeneity of risk ratios across strata of propensity score, based on overlap of confidence intervals for stratum-specific risk ratios (Table 2). Because there were no perpetrators among men who had witnessed violence in the lowest propensity-score stratum of any witnessing, or in the lowest 2 propensity strata for frequent or serious witnessing, we also tested models excluding these strata. Results were essentially unaffected. Results were also not meaningfully different in models that included potential confounders with imbalance greater than 0.1.

Childhood emotional support was only very weakly associated with reduced perpetration in models of any witnessing (moderate support, adjusted RR = 0.9 [0.6 –1.2]; high support, 0.9 [0.7–1.3]) or frequent or serious witnessing (moderate support, 0.8 [0.5–1.2]; high support, 0.9 [0.6– 1.3]). Emotional support was similarly not protective against reported perpetration in models restricted to men who had witnessed intimate partner violence, or in models where emotional support was included as a continuous variable.

DISCUSSION

Our results provide evidence that observing intimate partner violence in childhood increases the risk of later perpetration for men by an estimated 56% or 63%, depending on severity. These results indicate that previously-reported unadjusted estimates of the association between witnessing intimate partner violence on adulthood outcomes are to a large extent attributable to a constellation of adverse circumstances experienced by child witnesses. Furthermore, we found that children who witness more frequent or serious intimate partner violence have correspondingly greater exposures to other potentially-harmful events, possibly explaining why studies of children in shelters have found stronger relationships between witnessing intimate partner violence and psychologic, social, and educational outcomes than have population-based studies.6,13,23 It is possible that the association of witnessing very severe, frequent events with perpetration exceeds the estimates presented here, but we did not examine that level of exposure. Propensity-score modeling may be particular useful as an efficient way to adjust for many potential childhood confounders in small- or medium-sized samples.

We did not find that family emotional support in childhood provided measurable protection against later perpetration. Many studies finding that family support protects against the negative effects of exposure to violence focus on community violence rather than family violence.19,20 Some men who report high levels of family emotional support despite having witnessed intimate partner violence may identify with the perpetrator or fail to distance themselves from family violence—both characteristics associated with later perpetration.5

Although witnessing intimate partner violence in childhood was associated with an increased risk of perpetrating intimate partner violence, the risk of perpetrating among witnesses was still low: 91% of men who witnessed frequent or serious violence had not perpetrated in the past year. Furthermore, the majority of perpetrators (71%) had not witnessed any intimate partner violence in childhood, indicating that other factors account for the majority of male intimate partner violence perpetration in the United States.

Our finding of an association of witnessing intimate partner violence with later perpetration, after adjusting for a wide range of potential confounders, indicates that efforts to identify and assist individuals who have witnessed such violence in childhood should continue to receive support. However, our finding that 71% of perpetrators reported not having witnessed intimate partner violence in childhood signifies the need to understand other risk and protective factors across the lifespan, particularly those that may be modified to support nonviolent behavior. Many of the variables included in this propensity score for witnessing intimate partner violence have been recognized in prior research as potential causes of perpetration, although, as with the witness of intimate partner violence, determining causality is difficult due to possible confounding. Research is needed that examines these factors in models also including adulthood stressors, such as unemployment and substance abuse,3 to assess the pathways leading to perpetration to enhanced intervention strategies.

Existing research into intimate partner violence perpetration nonetheless offers several leads to modifiable factors that relate to perpetration, including improvement in verbal, social and marital communication skills, reducing attribution of hostile intent, and reducing the social acceptability of violence in intimate relationships.17

LIMITATIONS

This study relies on self-report of exposure, outcome, and confounders, which may mean that errors in measurement of these variables are correlated, possibly inflating associations between the witness of intimate partner violence and its perpetration. Moreover, propensity-score analysis does not account for confounders not included in the propensity-score model, such as childhood exposure to neighborhood violence and peers’ attitudes toward intimate partner violence perpetration, with the possibility of residual confounding. Omission of confounders is likely to inflate estimated effects. In contrast, social-desirability bias may attenuate estimated effects due to underreporting of perpetration. Although a study of social-desirability bias in reporting perpetration of intimate partner violence found small-to-moderate effect sizes,43 even small reductions in sensitivity can attenuate estimates. Furthermore, reports of childhood events were retrospective, possibly resulting in misclassification of exposure due to faulty recall, also attenuating effect estimates. However, in sensitivity analyses restricted to men aged 40 and younger, results were unchanged.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contribution of M. Maria Glymour toward clarifying causal models.

Supported by the Harvard Training Program in Psychiatric Genetics and Translational Research T32MH017119 (AR), NIH grant R01-MH54693 (GF), NIH grant RO3DA20887 (SG), and NIH grants K08MH070627 and 5R01MH078928 (KK).

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available through direct URL citations in the HTML and PDF versions of this article (www.epidem.com).

References

- 1.Catalano S, Smith E, Snyder H, Rand M. Bureau of Justice Statistics: selected findings. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs; 2009. Female victims of violence. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. 2002;359:1331–1336. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Magdol L, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Newman DL, Fagan J, Silva PA. Gender differences in partner violence in a birth cohort of 21-year-olds: bridging the gap between clinical and epidemiological approaches. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:68–78. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehrensaft MK, Cohen P, Brown J, Smailes E, Chen H, Johnson JG. Intergenerational transmission of partner violence: a 20-year prospective study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:741–753. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delsol C, Margolin G. The role of family-of-origin violence in men’s marital violence perpetration. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24:99–122. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stith SM, Rosen KH, Middleton KA, Busch AL, Lundeberg K, Carlton RP. The intergenerational transmission of spouse abuse: a meta-analysis. J Marriage Fam. 2000;62:640–654. [Google Scholar]

- 7.White HR, Widom CS. Intimate partner violence among abused and neglected children in young adulthood: the mediating effects of early aggression, antisocial personality, hostility and alcohol problems. Aggress Behav. 2003;29:332–345. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edleson JL. Men who batter women: a critical review. J Fam Issues. 1985;6:229–247. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alexander PC, Sharon M, Alexander ER., III What is transmitted in the intergenerational transmission of violence? J Marriage Fam. 1991;53:657–667. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Exposure to interparental violence in childhood and psychosocial adjustment in young adulthood. Child Abuse Negl. 1998;22:339–357. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(98)00004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Appel AE, Holden GW. The co-occurrence of spouse and physical child abuse: a review and appraisal. J Fam Psychol. 1998;12:578–599. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Mechanisms in the cycle of violence. Science. 1990;250:1678–1683. doi: 10.1126/science.2270481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Margolin G, Gordis EB. The effects of family and community violence on children. Annu Rev Psychol. 2000;51:445–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edleson JL. Children’s witnessing of adult domestic violence. J Interpers Violence. 1999;14:839–870. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cummings EM, El-Sheikh M, Kouros CD, Buckhalt JA. Children and violence: the role of children’s regulation in the marital aggression-child adjustment link. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2009;12:3–15. doi: 10.1007/s10567-009-0042-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koenen KC, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Taylor A, Purcell S. Domestic violence is associated with environmental suppression of IQ in young children. Dev Psychopathol. 2003;15:297–311. doi: 10.1017/s0954579403000166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holtzworth-Munroe A, Meehan JC, Herron K, Rehman U, Stuart GL. Testing the Holtzworth-Munroe and Stuart (1994) batterer typology. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:1000–1019. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.6.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen RA, Brumm V, Zawacki TM, Paul R, Sweet L, Rosenbaum A. Impulsivity and verbal deficits associated with domestic violence. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2003;9:760–770. doi: 10.1017/S1355617703950090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kliewer W, Murrelle L, Prom E, et al. Violence exposure and drug use in Central American youth: family cohesion and parental monitoring as protective factors. J Res Adolesc. 2006;16:455–477. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gorman-Smith D, Henry DB, Tolan PH. Exposure to community violence and violence perpetration: the protective effects of family functioning. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2004;33:439–449. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3303_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Edwards VJ, Williamson DF. Exposure to abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction among adults who witnessed intimate partner violence as children: implications for health and social services. Violence Vict. 2002;17:3–17. doi: 10.1891/vivi.17.1.3.33635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hines DA, Saudino KJ. Genetic and environmental influences on intimate partner aggression: a preliminary study. Violence Vict. 2004;19:701–718. doi: 10.1891/vivi.19.6.701.66341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kitzmann KM, Gaylord NK, Holt AR, Kenny ED. Child witnesses to domestic violence: a meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:339–352. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holt S, Buckley H, Whelan S. The impact of exposure to domestic violence on children and young people: a review of the literature. Child Abuse Negl. 2008;32:797–810. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bingenheimer JB, Brennan RT, Earls FJ. Firearm violence exposure and serious violent behavior. Science. 2005;308:1323–1326. doi: 10.1126/science.1110096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lunceford JK, Davidian M. Stratification and weighting via the propensity score in estimation of causal treatment effects: a comparative study. Stat Med. 2004;23:2937–2960. doi: 10.1002/sim.1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Messer LC, Oakes JM, Mason S. Effects of socioeconomic and racial residential segregation on preterm birth: a cautionary tale of structural confounding. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171:664–673. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grant B, Kaplan K. Source and accuracy statement for the wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruan WJ, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, et al. The alcohol use disorder and associated disabilities interview schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of new psychiatric diagnostic modules and risk factors in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;92:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Straus M, Gelles R. Physical Violence in American Families: Risk Factors and Adaptations to Violence in 8,145 Families. New Brunswick: Transaction Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Krueger RF, et al. Do partners agree about abuse in their relationship? A psychometric evaluation of interpartner agreement. Psychol Assess. 1997;9:47–56. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wyatt GE. The sexual abuse of Afro-American and white-American women in childhood. Child Abuse Negl. 1985;9:507–519. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(85)90060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou PS, Kay W, Pickering R. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of alcohol consumption, tobacco use, family history of depression and psychiatric diagnostic modules in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;71:7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Austin PC, Grootendorst P, Anderson GM. A comparison of the ability of different propensity score models to balance measured variables between treated and untreated subjects: a Monte Carlo study. Stat Med. 2007;26:734–753. doi: 10.1002/sim.2580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Begg CB, Gray R. Calculation of polychotomous logistic regression parameters using individualized regressions. Biometrika. 1984;71:11–18. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The bias due to incomplete matching. Biometrics. 1985;41:103–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ho DE, Imai K, King G, Stuart EA. Matching as nonparametric preprocessing for reducing model dependence in parametric causal inference. Polit Anal. 2007;15:199–236. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Austin PC. The relative ability of different propensity score methods to balance measured covariates between treated and untreated subjects in observational studies. Med Decis Making. 2009;29:661–677. doi: 10.1177/0272989X09341755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raghunathan TE, Solenberger PW, Hoewyk JV. IVEware: Imputation and Variance Estimation Software Survey Methodology Program. Ann Arbor, MI: Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raghunathan TE, Lepkowski JM, Hoewyk JV, Solenberger P. A multivariate technique for multiply imputing missing values using a sequence of regression models. Surv Methodol. 2001;27:85–95. [Google Scholar]

- 41.SUDAAN Release 9.0.3 (Windows Network SAS-Callable version) Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Normand ST, Landrum MB, Guadagnoli E, et al. Validating recommendations for coronary angiography following acute myocardial infarction in the elderly: a matched analysis using propensity scores. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:387–398. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00321-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sugarman DB, Hotaling GT. Intimate violence and social desirability—a meta-analytic review. J Interpers Violence. 1997;12:275–290. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.